Abstract

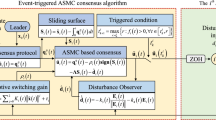

This paper proposes an adaptive prescribed-time periodic sliding mode control method to address the issue of singular disturbances in the rapid convergence of unmanned surface vehicle (USV) formation control. Firstly, preset performance ensures that the formation error of the closed-loop control system converges within a predefined allowable range. An adaptive control gain function is introduced to adjust the control gain in real-time according to the system state. Secondly, considering the unknown control direction, a periodic sliding mode method is proposed to maintain the robustness of the tracking project, and virtual signals and actual control laws are defined. Furthermore, this method ensures that the tracking error converges to zero within a user-defined time frame, regardless of the initial conditions. Simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of this method, providing a new solution for the rapid convergence and stable control of unmanned surface vehicle formations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of unmanned surface vehicle technology, unmanned surface vehicle formation plays an increasingly important role in the marine field1,2,3. The rapid development of this technology not only makes the tasks in the fields of marine survey4, resource exploration5, and maritime rescue6 more efficient and safe, but also provides a new means of marine scientific research and marine environmental monitoring. Some outstanding advantages of the unmanned surface vehicle formation system such as improving efficiency, reducing cost, enhancing mission flexibility7, etc. have attracted much attention. However, it is accompanied by many challenges in practical applications, such as the non-linear characteristics of the system, unknown environmental factors, and the design of control strategy. Nonlinearity is the inherent characteristic of USV cluster control system, which increases the complexity of controller design.

In the field of unmanned surface vehicle cluster control method, many scholars have made a lot of research. There are many methods and algorithms used to study the group control problem of USV, such as behavior-based formation control methods8, artificial potential field methods9, limited field of view10 and others. Considering the environment and control delays of USVs, Wu et al.11 proposed a new reward function that optimizes waiting time at path corners, thereby reducing coordination time among USVs; Wang et al.12 introduced a time-synchronized formation control method, enabling all state components to converge to the equilibrium point simultaneously with a time constant; Sun et al.13 investigated the autonomous navigation system for USV formations, where individuals within the formation possess a certain degree of autonomy to adjust the safety and length of the planned paths; Jin et al.14 proposed a distributed soft formation obstacle avoidance strategy, solving the problem of formation obstacle avoidance for USVs with limited observation capabilities and under complex environmental disturbances, contributing to USV swarm control; Mu et al.15 adopted a leader-follower approach and minimum learning parameter techniques to study formation tracking control for multiple underactuated USVs, enhancing the robustness of the control system.

In the complex marine environment, the unmanned ship cluster may be affected by wind and waves and other factors, resulting in the deviation of navigation trajectory and speed, which brings challenges to the controller design. At this point, a rapidly converging control system can quickly adjust the state of the USVs, restoring them to the expected trajectories and speeds, thereby enhancing the anti-interference capability and stability of the USV swarm. Meanwhile, a rapidly converging control system can more effectively achieve coordination and collaboration among USVs, thus improving the cooperative performance of the swarm. To optimize convergence speed, Liu et al.16 studied event-triggered finite-time tracking control for USV swarms; Jiang et al.17 designed a fully distributed adaptive containment controller with the help of finite-time differentiators, etc.; Shen et al.18 proposed a fixed-time formation control strategy based on an accurate disturbance observer (ADO), which has advantages for USV formation control; Liu et al.19 integrated a non-singular fast terminal sliding mode into a fixed-time control framework, improving the robustness and convergence speed of the USV system. The aforementioned research has made academic contributions to increasing the convergence speed of USV swarms. However, it can be observed that there is little research on preset-time convergence control for USV swarms.

Furthermore, the impact of external disturbances on USV formation systems is also an issue that needs to be considered. Mu et al.20 treated unknown dynamics and external disturbances as a whole and used minimum learning parameter techniques to compensate for them; Li et al.21 adopted an improved state observer based on the fal function to deal with unknown disturbances caused by the unknown environment during formation; Mu et al.22 studied the impact of disturbances such as water currents on the paths of USV swarms and proposed a path planning compensation strategy. To address the problem of formation obstacle avoidance for USVs with limited observation capabilities and under complex environmental disturbances, Jin et al.23 proposed a distributed formation obstacle avoidance strategy to improve robustness against unknown environmental disturbances. However, the aforementioned research did not take into account the phenomenon of unknown signal switching control directions that may occur in practical applications. Unknown disturbances can lead to abnormal directional changes in USV swarm control, resulting in an abnormal jump in control and degrading the system’s control performance.

In response to the aforementioned research, a preset-time adaptive periodic sliding mode control method is proposed, which can address the issue of singular disturbances in the rapid convergence of USV swarm control. It is necessary to consider the robustness to singular disturbances and the need to adapt to multi USV cooperative control while ensuring the stability and rapid convergence of the system. An adaptive preset-time control approach is designed to ensure that the USV formation rapidly reaches a stable state within a preset time, enhancing the overall system performance. Considering the switching of control directions caused by external unknown disturbance signals that deviate the control system from its intended stable state, we develop a periodic sliding mode control technique to maintain the inherent effectiveness of the USV tracking scheme even when the sign of control direction switching is unknown. Furthermore, the design of the adaptive controller employs adaptive techniques to acquire system state information in real-time and update control parameters, a process involving continuous time variation. To reduce computational burden, rather than using time-varying functions for state transformation, we appropriately apply this process to the design of the adaptive controller, avoiding the uncertainties introduced by time variation and improving system adaptability.

In the penultimate paragraph of the introduction, we changed.

-

1.

An adaptive scheduled time periodic sliding mode control method is proposed by this paper. Compared with24,25, this method combines the advantages of scheduled time control and periodic sliding mode method, and realizes the rapid convergence and robust tracking of USV cluster under singular disturbance.

-

2.

Compared with23, this paper considers the sensitivity of the system to unknown interference signals. By introducing the virtual signal and the actual control law, this paper designs a periodic sliding mode controller, which can maintain the tracking effectiveness and improve the robustness of the system when the control direction switching symbol is unknown.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In section “Problem description”, the dynamic model of the unmanned surface vehicle (USV) is described, and its main control objectives are introduced. In section “Design of formation controller”, the stability proof of the proposed control scheme is presented. Section “Simulation” validates the effectiveness of the control scheme proposed in this paper through simulation experiments. Finally, section “Conclusion” presents the conclusions of this paper.

Problem description

The digital model for USVs is described as follows:

The water surface coordinate system is denoted as \({O_{\text {e}}}{X_e}Y\), and the system coordinate system is represented by \({o_b}{x_b}{y_b}\). The formation system comprises N USVs. Let the model26 of \({i_{th}}\) USV be:

In the formula, the coordinates of the \({i_{th}}\) USV under \({O_{\mathrm{{e}}}}{X_e}Y\) are represented as \(\left( {{x_i},{y_i}} \right)\), the course angle is denoted as \({\varphi _i}\), the speed of disembarking the \({i_{th}}\) USV under \({o_b}{x_b}{y_b}\) is given by \({u_i}\), \({v_i}\) and \({r_i}\) represent the yaw velocity and the angular velocity, respectively, satisfying \({\eta _i} = {\left[ {{x_i},{y_i},{\varphi _i}} \right] ^T}\), \({V_i} = {\left[ {{u_i},{v_i},{r_i}} \right] ^T}\), \(i = 1,2...,n\). The control input of the \({i_{th}}\) USV is \({\tau _i} = {\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\tau _{iu}}}&0&{{\tau _{ir}}} \end{array}} \right] ^T}\). The Coriolis force and centripetal acceleration matrix of the USV are \({C_i}\left( {{v_i}} \right)\), \({C_i}\left( {{v_i}} \right) = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 0& 0& { - {m_{22}}{v_i}}\\ 0& 0& {{m_{11}}{u_i}}\\ {{m_{22}}{v_i}}& { - {m_{11}}{u_i}}& 0 \end{array}} \right]\). The damping matrix of the USV is \({D_i}\left( {{v_i}} \right)\),\({D_i}\left( {{v_i}} \right) = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{d_{11}}}& 0& 0\\ 0& {{d_{22}}}& 0\\ 0& 0& {{d_{33}}} \end{array}} \right]\); \({M_i}\) is the inertia matrix in the inertial coordinate system,\({M_i} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{m_{11}}}& 0& 0\\ 0& {{m_{22}}}& 0\\ 0& 0& {{m_{33}}} \end{array}} \right].\)

Formation model of USVs

In this study, the leader-follower approach is employed to regulate the formation of USVs. As shown in Fig. 1, designating one USV as the leader. The entire formation assumes a leader-follower structure based on the movement trajectory of the leader. Positions \(\left( {{x_{il}},{y_{il}}} \right)\) and \(\left( {{x_{if}},{y_{if}}} \right) (i = 1,2,3...n)\) represent the leader and the follower USV, respectively. The distance between the two USVs is denoted as L , with transverse and longitudinal distances labeled as \({L_x}\) and \({L_y}\) . The heading of the leader USV and the follower USV are designated as \({\varphi _{il}}\) and \({\varphi _{if}}\) , respectively. To maintain a constant distance between the USVs, we control both the expected distance \({L_d}\) and the true distance L between the leader USV and the follower USV.

In Fig. 2, the relative position relation between the leader USV and the follower USV is:

Taking the derivative on both sides yields:

Assuming the transverse expected distance between two unmanned ships is denoted as \({L_d}_{_x}\), and the longitudinal expected distance is denoted as \({L_d}_{_y}\) , then:

where, \({\theta _d}\) expresses the expected relative angle between the leading ship and following ship, and \({L_d}\) expresses the expected relative distance between the leading ship and following ship. At this juncture, the errors in the x and y directions are:

In summary, the USV formation model is as follows:

Where \({\tau _{iuf}}\) and \({\tau _{irf}}\) represent the forward thrust and bow rol moment of the following ship, respectively. In the formula:

Formation control objectives

In this section, we provide a detailed exposition of the specific goals of formation control, integrating key concepts from sliding mode control (SMC) and equivalent control. Additionally, we introduce pertinent assumptions guiding our control design.

Formation control objectives

In this section, The specific objectives of formation control and the associated fundamental assumptions are elaborated upon.

Given the non-linear system below with unknown control coefficients:

Our primary aim is to achieve these control objectives through the design of a state feedback control law \({\tau _f}:\)

-

1.

Signal Boundedness: Ensure the boundedness of all signals within the closed loop system.

-

2.

Precise Tracking: On the premise of ensuring performance,attain precise tracking of the output y(t) to a desired command \({y_r}(t)\). The tracking error \(\left| {e(t)} \right. = y(t) - \left. {{y_r}(t)} \right| < \rho (t)\) is constrained for \(t > 0\) in which the \(\rho (t)\) is a performance bound function and it is differentiable, bounded, positive, and exhibits a decreasing behavior over time.

-

3.

Asymptotic Precise Tracking: Expect the system to achieve asymptotic exact tracking, emphasizing convergence towards precise long-term formation.

Additionally, we introduce the following fundamental assumptions to guide the control design:

Assumption 1

27The required command \({{y}_{r}}(t)\) is bounded, continuous, and smooth. The derivative \({{{\dot{y}}}_{r}}(t)\) is also bounded.

Assumption 2

Positive constants \({{\bar{b}}_1}\) and \({\underline{b}}_1\) are defined such that \(0 < {\underline{b}}_1 \le \left| {{b_1}} \right. \left. {({x_1},...,{x_i})} \right| \le {{\bar{b}}_1}\) for \(i = 1,...,n.\)

Integration with sliding mode control concepts

Consider a dynamical system described by the equation:

Here, \(x(t) \in R\) represents the system state, and \(\Pi (t) \in R\) is an unknown bounded disturbance. The control input \(\tau (t)\) is designed using SMC:

In SMC, the gain function \(k(t) > \left| \Pi \right. \left. {(t)} \right|\) ensures sliding mode motion, leading to \(x(t) = 0\) in limited time. Equivalent control refers to the average control value required to remain ideal sliding motion, which can be expressed as:

Definition 1

28,29Equivalent control can be used as a control action required to hold ideal sliding motion. According to the non-linear system (7), the equivalent control \({\tau _{eq}}(t)\) is received by \({\tau _{eq}}(t) = - \Pi (t)\) because of \({\dot{x}}(t) = 0\) during sliding motion.

In this context, \({\tau _{eq}}(t)\) encapsulates the unknown disturbance information, facilitating the construction of an adaptive algorithm for chattering suppression30,31.

While the theoretical equivalent control \({\tau _{eq}}(t)\) is inaccessible, a close approximation \({{\bar{\tau }} _{eq}}(t)\) is obtained through low-pass filtering the actual control \(\tau (t)\) . This process is theoretically demonstrated by the part below:

Lemma 1

28,30Filtering a discontinuous signal \(\tau (t)\) with a low pass filter

yields a bounded output \({{\bar{\tau }} _{eq}}(t)\) and its derivative \({\dot{\bar{\tau }}_{eq}}(t).\) Furthermore, the output \({{\bar{\tau }}_{eq}}(t)\) satisfies \(\left| {{{{\bar{\tau }} }_{eq}}} \right. \left. {(t) - {\tau }} _{eq} \right| \le O(\tau ) \rightarrow 0\) as \(\tau \rightarrow 0\) during sliding motion.

System stability and controller design

According to (5), we can get:

Definition 2

According to the above system, if the controller has adaptive law

Under the controller (2), the trajectories of \(\Theta (t)\) and the state variables are bounded. Under the condition \({\mathop \textrm{V}\nolimits } (t) = 0\) \(\forall t \ge {T_p}\) and for a positive constant \({{\mathop \textrm{T}\nolimits } _p}\) the equilibrium points of above system are referred to as the locally defined time stable point, and the prescribed time \({{\mathop \textrm{T}\nolimits } _p}\) (expressed as local \({{\mathop \textrm{T}\nolimits } _{p - tps}}\) ) has nothing to do with the initial conditions of the system. Particularly, if \({\mathop \textrm{V}\nolimits } (0) \in {\mathop \textrm{R}\nolimits }\) , the balance point of system (1) is referred to as the globally defined time stable point (expressed as global \({{\mathop \textrm{T}\nolimits } _{p - pts}}\) ).

Lemma 2

32Considering a continuous function \(g(y) \ge 0\) defined on the interval \(y \in \left[ {a,b} \right)\) with a discontinuity at \(y = b,\) if it meets the following condition:

The improper integral \(\int _a^b {g(y)dy = + \infty }\) diverges when d is a finite constant or tends to positive infinity.

Definition 3

If a continuous function meets the following condition:

In which, \(\rho\) is a positive constant or positive infinity, and \(\mathrm{{\mu (t)}}\) is referred to as the regulated time adjustment function (\({\mathrm{{T}}_{\mathrm{{p}}}}\mathrm{{ - PTA}}\)).

Remark 1

Given that the Definition 3, it can be demonstrated that \(\mathop {\lim }\limits _{t \rightarrow T_p^ - } \mu (t) = + \infty\) . Furthermore, Lemma 3 facilitates an easy observation of \(\int _0^{{T_p}} {\mu (t)dt = + \infty }\). It follows naturally that the \({T_p} - PTA\) function satisfies all conditions defined for T-finite-time stable (T-FTS) functions in reference33, thereby being considered a T-FTS function as well. Various functions meet the definition of the function \({T_p} - PTA\), including \(\frac{1}{{{{\left( {{T_p} - t} \right) }^k}}}(k \ge 1)\) , etc.

Theorem 1

Considering system (1) equipped with a controller (2), if there have two positive continuous and differentiable functions \({V_1}(x(t))\) and \({V_2}({\tilde{\theta }} (t))\) , along with a class \({K_\infty }\) function \({a_w}(w = 1,2,3,4)\) , meeting conditions

where u(t) has been defined in Definition 2 mentioned earlier, and c is a normal number, after that the equilibrium point of system (1) is globally defined as time steady.

Proof

The proof can be elaborated from the following two parts. Part A: Under the controller (2), the tracks of x(t) and \(\theta (t)\) are bounded. Part B: The solution x(t) of system (1) converges to zero at the specified time \({T_p}.\)

Part A: Form (17), we can get

Therefore, V(t) is monotonically decreasing for \(t \in \left[ {0,{T_p}} \right)\). Next, from (14), we can get

Then, according to (15), (16), and (18), we can get

ensuring that both x(t) and \({\tilde{\theta }} (t)\) are bounded. Due to \({\hat{\theta }} (t) = \theta - {\tilde{\theta }} (t)\), We can draw a conclusion that \(\mathop \theta \limits ^{\frown }(t)\) is bounded for any \(t \in \left[ {0,{T_p}} \right) .\)

Part B: To begin with, integrating both sides of equation (17), we obtain

Subsequently, it can be transformed into \(\int _0^{{T_p}} {c\mu {V_1}dt} \le C\), where \(C = V(0) - V(T_p^ - )\) is a constant. Thus, we can conclude that \(\int _0^{{T_p}} {c\mu {V_1}dt}\) is bounded.

In the following, we will employ a contradiction method to prove the convergence of x(t) to zero at the prescribed time \({T_P}.\)

Firstly, we are working on the assumption that

Here, \(\beta\) is a positive constant. Due to \(\mathop {\lim }\limits _{t \rightarrow T_p^ - } \mu (t) = + \infty\) , it causes \(\int _0^{{T_p}} {c\mu {V_1}dt}\) becoming an inappropriate point of an unbounded function with \({T_P}\) singularity.

For one thing, due to the monotonic increasing nature of \(c\mu {V_1} \ge 0\) over the interval \(\left[ {0,{T_P}} \right)\) and \(F(\tau ) \le C,\) \(\int _0^{{T_p}} {c\mu {V_1}dt}\) is convergent. On the other hand, since \(\mathop {\lim }\limits _{t \rightarrow {T_p}^ - } ({T_p} - t)\sigma \mu {V_1} = c\rho \varepsilon > 0\) , we can deduce that the improper integral \(\int _0^{{T_p}} {c\mu {V_1}dt}\) diverges in accordance with Lemma 3.

Upon comparison, we observe that the contents of these two fields are contradictory. Thus, assuming Eq. (20) cannot be satisfied, which shows \(\mathop {\lim }\limits _{t \rightarrow {T_p}^ - } {V_1} = \varepsilon = 0\) . Additionally, according to Eq. (15), it can be inferred that \(\mathop {\lim }\limits _{t \rightarrow {T_p}^ - } x = 0\) . Firstly, by leveraging the existence and continuity of solutions x(t), we obtain \(x({T_p}) = 0\) and \(u({T_p}) = 0\) . Subsequently, due to \(f(t,x(t),u(t),\theta )\) being zero at the origin, and for \(\forall t \ge {T_p}\) , \(u(t) = 0\) , we have \(x(t) = 0\) , \(\theta (t) = \theta ({T_p})\) . Based on Definition 1, two parts of proof, we conclude that the equilibrium point of system (1) is globally defined and time steady. Prove that it has been completed. \(\square\)

Remark 2

Through the proof of Theorem 1, we observe that as \(t \rightarrow {T_p}\), V monotonically decreases and skews toward to be constant, \({V_1}\) converges to zero, and \({V_2}\) remains bounded. Additionally, for \(t > {T_p}\), \(V(t) = {V_2}(t),\) and \({V_1}(t) = 0.\)

Remark 3

For system (1), if the parameters \(\theta\) is known and Theorem 1 holds, setting \({V_2} = 0\), (17) reduces to

Considering Remark 2, we can ascertain that u(t) is considered as the T-FTS function in reference34. Hence, (21) is equivalent to Eq. (7). In general, for some systems, Theorem 1 in this article can be converted to Theorem 1 in reference35.

Remark 4

In actual control systems, due to the limited energy that actuators can release, the control signal u(t) cannot be infinitely large34. Therefore, it is essential to choose an appropriate \({T_p} - PTA\) function to ensure the bounteousness of the controller u(t).

Design of formation controller

Virtual quantity design

Base on the Sliding Mode Control, define the state vectors of the system \({z_1}\) and \({z_2}\) as:

Derive from \({z_1}\) and \({z_2}\), we can obtain:

Assuming \({u_f}\) and \({v_f}\) are the inputs of \(\left( {{z_1},{z_2}} \right)\) system, then \({u_{{f_\alpha }}}\) and \({v_{{f_\alpha }}}\) are separately the virtual quantities of \({u_f}\) and \({v_f}\). We consider the Lyapunov function as \({V_1} = \frac{1}{2}{z_1}^2 + \frac{1}{2}{z_2}^2\). Then \({u_{{f_\alpha }}}\) and \({v_{{f_\alpha }}}\) are obtained:

Where \({k_1},{k_2}\) are the design parameters. The velocity error is \({e_v} = {v_f} - {v_{{f_\alpha }}}\), its derivative is \({{\dot{e}}_v} = {{\dot{v}}_f} - {{\dot{v}}_{fa}},\) which is:

\({r_l}\) and \({r_f}\) represent the roll speed of the leading USV and the following USV respectively. \({u_f}\) and \({v_f}\) represent the longitudinal and lateral speeds following the USV, respectively.

Due to simplified control design, the back-stepping method is introduced. Therefore, we define the tracking error as:

Among (25), \({v_f}\) and \({v_{{f_\alpha }}}\) are system input and corresponding virtual quantity respectively. \({{\bar{\alpha }} _1}\left( t \right)\) represents the outputs of the following first-order filters:

where the constant \({\tau _1} > 0\) and \(\alpha (t)\) is virtual control signal. By introducing periodic sliding mode method, we can solve the problem with unknown control direction. Therefore, define the virtual signal \({\alpha _1}\) and the actual control law \({\tau _{irf}}\) as:

where R is the adaptive gain function, \(\operatorname {sgn}\) is the sign function, and \({\varepsilon _1}> 0,{\varepsilon _2} > 0\) are the normal number. \({\sigma _i}\) indicate the sliding mode surfaces represented by the equation below:

where \({\xi _i} > 0\) and \({c_i}>0\) are positive constants. And

where \({\rho _i}(t)\) is the pre selection bound performance function. From (2) of part B in Section II, \({\rho _i}(t)\) is a differentiable, bounded, positive, and decreasing function over time, typically chosen in the form of the following index:

where constants \({\rho _{i,0}}> {\rho _{i,\infty }} > 0\) and \({l_i} > 0\). It should be noted that the function \({\rho _i}(t)\) should meet with \({\rho _1}(0) > \left| {{v_f}(0) - {v_{fa}}(0)} \right|\) and \({\rho _2}(0) > \left| {{r_f}(0) - {\alpha _1}(0)} \right|\). In (28), the expression of adaptive control gain function is as shown below:

where \({r_{i,0}}\) is Positive scalar. And the adaptive term \({r_i}(t)\) can be derived from the following equation:

and:

where \({s_{i,0}}\), \({\mu _i}\) are normal numbers, \({E_i}\) are small positive scalars. The normal numbers \({h_i}\) meets with \(0< {h_i} < 1.\) In (25), taking the derivative of velocity error p yields:

where

From (23), the derivative of \({v_{fa}}\) is:

Because of \({{\dot{\xi }} _1} = \frac{{2{{{\dot{\eta }} }_1}(t)}}{{1 - {\eta _1}^2(t)}}\), and from (29) and (37), we can obtain:

where

Position controller design

The following part is intended to use a design controller to converge the actual velocity to the virtual expected velocity. When the velocity error approaches zero, the USV formation is in stable status. Design the speed error as \({e_u} = {u_{if}} - {u_{ifa}}\). After taking the derivative of the \({e_u}\), we can obtain that:

Let \({\theta ^T}{\kappa _2} = \frac{{{m_{2f}}}}{{{m_{1f}}}}{v_f}{r_f} - \frac{{{d_{1f}}}}{{{m_{1f}}}}{u_f} - {{\dot{u}}_{fa}}\) Prior to designing a controller, select the Lyapunov function as: \(V = {V_1} + {V_2}\). Where \({V_1}\) and \({V_2}\) are defined as:\({V_1} = \sum \limits _{i = 1}^n {o_j^2} ,{V_2} = \mathop {{\theta ^T}}\limits {\Gamma ^{ - 1}}\mathop \theta \limits\) Next, we will raise an adaptive specified time controller for any given time \({T_P}\). The design process can be separated into two situations: \(0 \leqslant t < {T_p}\) and \(t \geqslant {T_p}\).

Case 1 (\(0 \leqslant t < {T_p}\)): The following is the formula for state transformation:

where \({\beta _1}\) indicates the virtual controller. Next, we will design a timing controller based on the backstepping method. This method has two steps.

Step 1: The derivative of \({o_1}\) meets with

Design the virtual controller \({\beta _1}\) as

where \({\delta _{\text {1}}} > n\) is design parameter. The derivative of \({o_1}\) and \({W_1} = {o_1}^2 + {V_2}\) satisfy

where \({\Upsilon _1} = {o_2},{\Lambda _1} = 0.\)

Step 2: Considering (45) and (47), the derivative of \({o_2}\) meets with

Design the controller \(\tau\) and the adaptive as:

where \({\Lambda _2} = {\Lambda _1} + {o_2}{\kappa _2}\). And

Then, we can obtain that

where \({\Upsilon _2} = - {o_1} + {{\tilde{\theta }} ^T}{\kappa _2} + \frac{{\partial {\beta _1}}}{{\partial {\hat{\theta }} }}(\Gamma {\Lambda _2} - {\dot{\hat{{\theta }}}}) + {\kappa _2}\Gamma \frac{{\partial {\beta _1}}}{{\partial {\hat{\theta }} }}{o_2},\) \(\textrm{N}(t) = \frac{\delta }{{{T_p} - t}}\) is the function of \({T_p} - PTA\).

Case 2 (\(t \geqslant {T_p}\)): When \(t \geqslant {T_p}\), design the control signal and adaptive law as:

Attitude controller design

The angular velocity error can be defined as \({e_r} = {r_{if}} - {r_{fa}}\), derivation on both sides

Similarly, select the Lyapunov function as: \(V = {V_3} + {V_4}\), where \({V_3}\) and \({V_4}\) are defined as: \({V_3} = \sum \limits _{i = 1}^n {g_j^2} ,{V_4} = \mathop {{\theta ^T}}\limits {\Gamma ^{ - 1}}\mathop \theta \limits\)

Next, we will raise an adaptive specified time controller for any given time \({T_P}\). Similarly, we will discuss in two cases.

Case 1(\(0 \leqslant t < {T_p}\)): The following is the formula for state transformation:

where \({\beta _2}\) indicates the virtual controller.Next, we will design a timing controller based on the backstepping method. This method has two steps.

Step 1: The derivative of \({g_1}\) meets with

Design the virtual controller \({\beta _2}\) can as

where \({\delta _2} > n\) is design parameter. The derivative of \({g_1}\) and \({W_{\text {2}}} = {g_1}^2 + {V_4}\) satisfy

where \({\Upsilon _3} = {g_2},{\Lambda _3} = 0.\)

Step 2: According (45) and (47), the derivative of \({g_2}\) meets with

Design the controller \(\tau\) and the adaptive law as:

where \({\Lambda _4} = {\Lambda _3} + {g_2}{\kappa _3}\). And

Then, we can obtain that

where \({\Upsilon _2} = - {g_1} + {{\tilde{\theta }} ^T}{\kappa _3} + \frac{{\partial {\beta _2}}}{{\partial {\hat{\theta }} }}(\Gamma {\Lambda _4} - {\dot{{\hat{\theta }}}}) + {\kappa _3}\Gamma \frac{{\partial {\beta _2}}}{{\partial {\hat{\theta }} }}{g_2},\) and \(\textrm{N}(t) = \frac{\delta }{{{T_p} - t}}\) is the function of \({T_p} - PTA\).

Case 2 (\(t \geqslant {T_p}\)): When \(t \geqslant {T_p}\), design the control signal and adaptive law as follows:

Stability analysis

In this section, we provide the theorem below to analyze the bounteousness of uncertainty \({N_1}(t)\), \({N_2}(t)\) and closed-loop systems.

Theorem 1

Both Assumption 1and Assumption 2 hold, if design the controller as (27) and (28), and the control gain functions are designed as (33)–(35), then the following two conditions are met:

-

(a)

All signals in a closed-loop system are bounded.

-

(b)

For \(\forall t > 0\), the errors \({p_i}\) satisfy \(\left| {{p_i}(t)} \right| < {\rho _i}(t)\).

Theorem 1 can ensure that the preselected performance limit \({\rho _i}(t)\) meets the following condition: \(t \in \left[ {0, + \infty } \right)\). Moreover, the uncertainties \({N_i}(\) still has a boundary for \(t \in \left[ {0, + \infty } \right)\). For the following design process, the above explanation is very necessary.

When the synovium moves, we have:

It should be noted that \({N_1}\) and \({b_0}\) are unknown, so the equivalent control signals \({\alpha _{1,eq}}\) are also unknown. But we can introduce filters as \({\varphi _{1}}{{\dot{-}} \alpha _{1,eq}} + {{\bar{\alpha }} _{{1,eq}}} = au\) which can obtain approximate value \({{\bar{\alpha }} _{{1,eq}}}\) according to Theorem. Then, add \({{\bar{\alpha }}_{{1,eq}}}\) to the adaptive scheme (35).

Theorem 2

Both Assumption 1and Assumption 2hold. According to the control law (27) and (28) with adaptive solutions (33)–(35), so we can achieve the following control objectives:

-

(a)

Adaptive gain \({R_i}(t)\) is still bounded.

-

(b)

The tracking error \({p_i}\) asymptotically converge to 0.

Proof

Define \({s_1}\) as \({s_1} = \int _0^t {{\mu _1}\left| {{X_1}(\theta )} \right| } d\theta\) and \({\lambda _1} = {s_1} + {s_{1,0}}\), where \({s_{1,0}}\) is a positive scalar. Equation \({{\dot{r}}_1}(t) = - {\lambda _1}\operatorname {sgn} \left( {{X_1}(t)} \right)\) and \({{\dot{s}}_1} = {\mu _1}\left| {{X_1}(t)} \right|\) hold. From Theorem 1, \(\left| {{N_1}} \right| \leqslant {{\bar{N}}_1}\) with an unknown normal number \({{\bar{N}}_i}\), the proof process is separated into the three stages below.

Phase 1: \({R_1}(t) < \frac{{{{\bar{N}}_1}}}{{{{ \underline{b} }_0}}}\)

This situation implies that the system is in the arrival stage, so we have \(|{\alpha _{\text {1}}}| = |{R_{\text {1}}}(t)| \cdot |\operatorname {sgn} \left( {\sin \left( {\frac{\pi }{{{\varepsilon _1}}}{\sigma _1}(t)} \right) } \right) | = |{R_{\text {1}}}(t)|\). Please take notice that there is currently no definition of equivalent control, so we take into account the approximate accuracy \(\left| {(\left| {{{{\bar{\alpha }} }_{1,eq}}(t)} \right| - \left| {({\alpha _1}(t)} \right| )} \right|\). Given that Lemma 2, there are scalars \({l_0} > 0,0< {l_1} < 1\). Then \(\left| {\left( {\left| {{{{\bar{\alpha }} }_{1,eq}}(t)} \right| - \left| {{\alpha _1}(t)} \right| } \right) } \right| < {l_1}\left| {{\alpha _1}(t)} \right| + {l_0}\) hold. This leads to \(\left| {{{{\bar{\alpha }} }_{1,eq}}(t)} \right| - \left| {{\alpha _1}(t)} \right| > - {l_1}\left| {{\alpha _1}(t)} \right| + {l_0}\), resulting in \(\left| {{{{\bar{\alpha }} }_{1,eq}}(t)} \right| > (1 - {l_1})\left| {{\alpha _1}(t)} \right| - {l_0}\). Noted that \({ \underline{b} _1} < {{\bar{b}}_1},E > \frac{{2{{\bar{b}}_1}{l_0}}}{{{h_i}{{ \underline{b} }_1}}}\) and \(0< {h_i} < 1 - {l_1}\). Then, it is obtained that:

Then, it is obtained that:

where \(\frac{{{{{\bar{b}}}_0}(1 - {l_1})}}{{{h_1}{{ \underline{b} }_0}}} > 1\) and \(\frac{{{{\bar{b}}_0}{l_0}}}{{{h_1}{{ \underline{b} }_0}}} - {E_1}< - \frac{{{{\bar{b}}_0}{l_0}}}{{{h_1}{{ \underline{b} }_0}}} < 0\), thus \({X_1}(t) < 0\) holds. After a period of time, \({R_1}(t) > \frac{{{{\bar{N}}_1}(t)}}{{{{ \underline{b} }_0}}}\) is satisfied.

Phase 2: \({R_{\text {1}}}(t) > \frac{{{{\bar{N}}_{\text {1}}}}}{{{{ \underline{b} }_{\text {0}}}}} \geqslant \frac{{\left| {{{{\bar{N}}}_{\text {1}}}(t)} \right| }}{{{{ \underline{b} }_{\text {0}}}}}\)

Define that \({w_{\text {1}}}(t) = {R_{\text {1}}}(t) - \frac{{\left| {{{{\bar{N}}}_{\text {1}}}(t)} \right| }}{{{{ \underline{b} }_{\text {0}}}}}\) which has constants \({w_{{\text {1}},0}} > 0\) such as \({w_{\text {1}}}(t) > {w_{{\text {1}},0}}\). Choose Lyapunov function candidates as \({V_{\text {1}}} = \frac{1}{2}{({\sigma _{\text {1}}}(t) - {k_{\text {1}}}{\varepsilon _{\text {1}}})^2}\), where \({k_{\text {1}}}\) is positive constants. Find the derivative of \({V_i}\) for t:

If the control function \({b_0} > 0\), then \({b_0} \geqslant { \underline{b} _0}\). If \({\sigma _1}(t) = {k_1}{\varepsilon _1}\) is satisfied with \({k_1}\) is odd, then \(\operatorname {sgn} \left( {\sin \left( {\frac{\pi }{{{\varepsilon _1}}}{\sigma _1}(t)} \right) } \right) = - \operatorname {sgn} ({\sigma _1}(t) - {k_1}{\varepsilon _1})\) is met. And (66) can be expressed as:

Otherwise \({b_0} < 0\), \({b_0} \leqslant - { \underline{b} _0}\) in the field of \({\sigma _1}(t) = {k_1}{\varepsilon _1}\) with \({k_i}\) is even, then \(\operatorname {sgn} \left( {\sin \left( {\frac{\pi }{{{\varepsilon _1}}}{\sigma _1}(t)} \right) } \right) = \operatorname {sgn} ({\sigma _1}(t) - {k_1}{\varepsilon _1})\) is met. And (66) can be expressed as:

Therefore, it can be noted that \({\rho _{1,0}}< {\rho _1}(t) < {\rho _{1,\infty }}\) and \(0 < 1 - {\eta _1}^2(t) \leqslant 1\), and we can obtain that:

This represents that the sliding mode happens. Phase 3: When the system moves on the sliding surface, \({{\dot{\sigma }} _i}(t) = 0\) always holds true. According to Theorem 1, \({{\bar{\alpha }} _{1,eq}}(t)\) is bounded. Suppose \(\left| {{{{\bar{\alpha }} }_{1,eq}}(t)} \right| \leqslant {\bar{j}}\) has a positive scalar \({\bar{j}}\). Therefore, we can obtain the derivative of \({X_i}\left( t \right)\) on the sliding surface as shown below:

Substituting (33) into (70) yields:

where \(\frac{d}{{dt}}{\left\| {{\xi _1}} \right\| _t}{e^{ - {\varpi _1}t}}\) is bounded. Let \(\left| {{{{\bar{\alpha }} }_{1,eq}}(t)} \right| \leqslant {{\bar{j}}_1}\), \(\frac{d}{{dt}}\left( {{{\left\| {{\xi _1}} \right\| }_t}{e^{ - {\varpi _1}t}}} \right) \leqslant {M_1} - {s_1}\left( t \right)\), constants \({{\bar{j}}_1}\) and \({M_1}\) are Positive values but unknown. Define that \({K_1}\left( t \right) = \frac{{{{{\bar{b}}}_0}{{\bar{j}}_1}}}{{{h_1}{{ \underline{b} }_0}}} + {M_1} - {s_1}\left( t \right)\). The Lyapunov function candidates can be selected as:

where \({K_1}\left( t \right) = - {{\dot{s}}_1}\left( t \right) = - {\mu _1}\left| {{X_1}} \right|\) hold. Then, we can obtain that:

It’s obvious that when \(\forall t > 0\), \({X_i}(t)\) and \({e_i}(t)\) are bounded. Consequently, the adaptive gain R(t) remains bounded, ensuring the target (1). According to LaSalle invariance principle36, it is follows that:

In the first phase, it is follows that \(\left| {{{{\bar{\alpha }} }_{1,eq}}(t)} \right| > (1 - {l_1})\left| {{\alpha _1}(t)} \right| - {l_0}\). Then (74) yields

Where the function \({B_i}(t) = \frac{{{{\bar{b}}_0}}}{{{{ \underline{b} }_0}}}\), and \({B_i}(t) \geqslant 1\). From (64), we can get \(\left| {{b_0}{\alpha _{1,eq}}(t)} \right| = \left| {{N_1}} \right|\).

And thus

Where \({E_{\text {1}}} > \frac{{2{{\bar{b}}_{\text {1}}}{l_0}}}{{{h_1}{{ \underline{b} }_0}}}\) and \(0< {h_1} < 1 - {l_1}\), then \(- \frac{{{{\bar{b}}_0}{l_0}}}{{{h_1}{{ \underline{b} }_0}}} + \frac{{{E_{\text {1}}}}}{2} > 0\) and \(\frac{{\left| {{B_1}} \right| (1 - {l_1})}}{{{h_1}}} >\) hold. This led to \({R_{\text {1}}}(t) \geqslant \frac{{\left| {{N_1}} \right| }}{{{{ \underline{b} }_1}}}\).

Noted that on the synovial surface, \({\sigma _1}(t) = {k_1}{\varepsilon _1}(\) and \({{\dot{\sigma }} _1}(t) = 0\) are satisfied, we can get that \({{\dot{\sigma }} _1}(t) = {{\dot{\xi }} _1}(t) + \frac{{{c_1}{\xi _1}(t)}}{{{\rho _1}(t)(1 - {\eta _1}^2(t))}} = 0\). Select the Lyapunov function as \({W_{_1}}\left( t \right) = \frac{1}{2}{\xi _1}^2\), and it is follows that:

\(\square\)

Simulation

Simulation parameter setting

The parameter settings for the USV are specified as follows:

Based on (5) and (44), the following system is obtained:

In Equation (51), we stipulate that:

when \({T_p} = 0.5s\),the simulation results can be shown in Figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7.

Based on the attitude model (7),

In this paper, the time-varying parameter \(\mathrm{{\theta }}(\mathrm{{t}})\) is regarded as the controlling direction. To account for possible signal switching of the control direction, based on the models \({B_1} = \frac{{{m_{11}}}}{{{m_{22}}}}{u_f}\), \({B_2} = \frac{{{b_1}}}{{{m_{22}}}}\theta\),the control parameter \(\mathrm{{\theta (t)}}\) meets with the following conditions:

In this scenario, the control direction in \(\mathrm{{t = 0}}\mathrm{{.05}}\) . The initial conditions are set as \({v_f} = {r_f} = 0.01\) , with \({{\bar{b}}_1} = 1000\) , \({{\underline{b}}_1} = 1\); \({{\bar{b}}_2} = 1000\),\({{\underline{b}}_2} = 1\) . The control objective is to force the output to track the required output \({v_{fa}} = \sin (\frac{\pi }{2}t)\) when satisfying the constraints of the following performance functions:

Set the control parameters to: \({\text{c}}_{1} = 0.5,\) \(\varepsilon _{1} = 2,\) \(\psi _{1} = 0.015,\) \({\text{E}}_{{\text{1}}} = 0.11,\) \({\text{r}}_{{1,0}} = 0.23;\) \(\mu _{1} = 0.5,\)\(s_{{1,0}} = 13.5,\) \(h_{1} = 0.8,\) \(\beta _{1} = 1,\)\(\tau _{1} = 0.25;\) \(c_{2} = 2,\) \(\varepsilon _{2} = 3,\) \(\psi _{2} = 0.035,\) \(E_{2} = 0.11,\) \(r_{{2,0}} = 15.5,\) \(\mu _{2} = 0.5,\) \(s_{{2,0}} = 22.5,\) \(h_{2} = 0.75,\) \(\beta _{2} = 1.\) The simulation results can be shown in Figs. 8 and 9.

The simulation result

Figure 3 presents the USV swarm trajectories based on the preset-time adaptive periodic sliding mode control method mentioned in (28). The figure shows the two-dimensional trajectories of five vessels. It can be observed that as the routes of the vessels extend, the curves of different vessels exhibit similar trends overall. This indicates that the swarm control method can enable multiple vessels to maintain a certain level of coordination and adaptability. Figure 4 is a chart showing the variation of the USV’s position error on the X-axis over time. As the USV’s sailing route swings in Fig. 3, the data points fluctuate above and below the zero-error line, with the error values ranging from − 0.025 to 0.025 m, indicating that the position error of the USV on the X-axis is relatively small.Similarly, Fig. 5 presents the variation of the USV’s position error on the Y-axis over a specific time period. The error values show a certain decreasing trend over time, and the error range is small, which can be considered as tending towards stability.

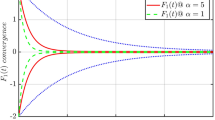

In Fig. 6, the red and black lines represent two state variables of the unmanned surface vehicle. Under the finite-time control method, these state variables remain stable only for a finite duration of time.After a certain point in time, the state variables will start to deviate from their stable values. Large errors in state variables may lead to a decrease in system stability. Especially in finite-time control methods, when the state variables deviate from their stable range, the system may become unstable, resulting in performance degradation or even loss of control. In Fig. 7, blue and green represent the error of the unmanned surface vehicles under prescribed-time control, while black and red represent the error under finite-time control. As shown in Fig. 7, this indicates that prescribed-time control is capable of accurately converging the error to zero within a predefined time period, exhibiting high control precision and stability. In contrast, finite-time control can only guarantee that the error remains bounded within a finite time, but cannot achieve zero-error precise control.

Figure 8 is used to demonstrate the variation of tracking error over time. As shown in Fig. 8, the tracking error converges approximately to zero around 0.05 s, even when considering disturbances and changes in the sign of the control direction. This indicates that the proposed control scheme remains effective. Figure 9 is an output curve that changes over time. The red dashed line represents the desired velocity value, which is a preset velocity curve that is expected to be achieved. The blue solid line \({v_{fa}}\) is the output velocity value. The blue solid \({v_a}\) line closely follows the red dashed line, indicating that the system performance is good and it can accurately track the desired velocity.

The simulation demonstrates the feasibility of our controller design.

Conclusion

This article delves into the adaptive prescribed-time control problem for unmanned surface vehicle (USV) formations, tackling complexities stemming from system nonlinearity, environmental uncertainties, and the intricacies of control strategy design. We introduce an innovative control approach grounded in prescribed-time and prescribed-performance control (PPC), initially defining prescribed-time stability. Subsequently, we present a tailored novel adaptive prescribed-time convergence theorem, leveraging it to devise a time-varying state feedback controller for uncertain nonlinear USV systems. This controller ensures tracking errors converge to zero within a user-defined time frame, independent of initial conditions, thereby enhancing flexibility and adaptability. Furthermore, it employs periodic sliding mode techniques to effectively handle uncertain control direction switches, while minimizing computational burden by forgoing complex time-varying state transformations. The experimental results show that the predetermined time control can converge the tracking error to zero within the user-defined time frame, regardless of the initial conditions. This feature provides strong support for the practical application of USV cluster in complex marine environment.In the future, the research on the control of unmanned surface vehicle cluster can explore more efficient adaptive control algorithm. For example, we can try to combine other advanced control algorithms, such as neural network control and fuzzy control, to improve the intelligent and adaptive ability of control.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Cheng, L. Y. Y. & Deng, B. Water target recognition method and application for unmanned surface vessels. IEEE Access 10, 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3138983 (2021).

Matteo-Schiaretti, R. R. N. & Linying, C. Survey on autonomous surface vessels: part ii—categorization of 60 prototypes and future applications. Comput. Sci. 10572, 456. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68496-3_16 (2017).

Devaraju, A. N. R. R. & Chen, L. Autonomous surface vessels in ports: applications, technologies and port infrastructures. Comput. Sci. 11184, 145. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00898-7_6 (2018).

Jia Wang, T. L. & Yang, X. A survey of technologies for unmanned merchant ships. IEEE Access 8, 224461–224486. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3044040 (2020).

Chen, F. & Yu, Q. Multiple unmanned ship coverage and exploration in complex sea areas. Autonom. Intell. Syst. 4, 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43684-024-00069-7 (2024).

Sar, A. B. Considerations on assistance and rescue at sea in the light of the increasing autonomy in ship. Mar. Policy 153, 105639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105639 (2023).

Liu, K., Wang, Y., Li, Y., Zhang, Y. & Wen, C. Y. Velocity-free adaptive neural-fuzzy predefined-time attitude control for spacecraft. In IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAES.2025.3526744 (2025).

Tan, G. Coordination control for multiple unmanned surface vehicles using hybrid behavior-based method. Ocean Eng. 232, 109147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.109147 (2021).

Sang, H. The hybrid path planning algorithm based on improved a* and artificial potential field for unmanned surface vehicle formations. Ocean Eng. 223, 108709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.109147 (2021).

Naderolasli, A. C. A. & Shojaei, K. Fixed-time multilayer neural network-based leader-follower formation control of autonomous surface vessels with limited field-of-view sensors and saturated actuators. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-024-10575-7 (2024).

Wu, D., He, M. & Lei, Y. Deep reinforcement learning-based path control and optimization for unmanned ships. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2023, 7135043. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9863680 (2023).

Wang, D. Time-synchronized formation control of unmanned surface vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 45. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2024.3371431 (2024).

Sun, X. & Wang, G. A formation autonomous navigation system for unmanned surface vehicles with distributed control strategy. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 22, 2834–2845. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2020.2976567 (2020).

Kefan Jin, J. W. Soft formation control for unmanned surface vehicles under environmental disturbance using multi-task reinforcement learning. Ocean Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.112035 (2022).

Yuyang Huang, W. L. Formation control for uav-usvs heterogeneous system with collision avoidance performance. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 2332. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse11122332 (2023).

Yuan Liu, L. Z. Event-triggered finite-time tracking control of unmanned surface vessel using neural network prescribed performance. IEEE Access 12, 11481–11491. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3347566 (2023).

Yuan Liu, L. Z. Adaptive prescribed-time containment control for multiple unmanned surface vehicles with uncertain dynamics and actuator dead-zones. Ocean Eng. 289, 116269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.116269 (2023).

Shen, Y. & Helong, Y. Fixed-time formation control for unmanned surface vehicles with parametric uncertainties and complex disturbance. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse10091246 (2022).

Chang, Z.-J. Fixed-time formation tracking for unmanned surface vehicles: a multi-layer neural networks approach. Neurocomputing 600, 128220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128220 (2024).

Mu, G. F. W. & Dong, D. Formation control strategy for underactuated unmanned surface vehicles subject to unknown dynamics and external disturbances with input saturation. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 18, 2742–2752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12555-019-0611-6 (2020).

Li, M. Research on unmanned surface vehicle formation and maintenance control based on improved extended state observer. Chinese Conf. Swarm Intell. Cooper. Control 1206, 667–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-3332-3_58 (2023).

Mu, D. Global path planning for unmanned surface vehicles in complex maritime environments considering environmental interference. Ocean Eng. 310, 118580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.118580 (2024).

Kefan Jin, J. W. Soft formation control for unmanned surface vehicles under environmental disturbance using multi-task reinforcement learning. Ocean Eng. 260, 112035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.112035 (2022).

Sui, J., Zhang, B. & Liu, Z. Prescribed-time dynamic positioning control for usv with lumped disturbances, thruster saturation and prescribed performance constraints. Remote Sens. 16, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16224142 (2024).

Feng, Z. & Pan, Z. Usv application scenario expansion based on motion control, path following and velocity planning. Machines 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines10050310 (2022).

Zou-Yuhan, S. W. & Wang, K. Back-stepping formation control of unmanned surface vehicles with input saturation based on adaptive super-twisting algorithm. IEEE Access 10, 114885–114896. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3217237 (2022).

Piao, Z. & Guo, C. Adaptive backstepping sliding mode dynamic positioning system for pod driven unmanned surface vessel based on cerebellar model articulation controller. IEEE Access 8, 48314–48324. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2979234 (2020).

Utkin, V. I. Adaptive sliding mode control with application to super-twisting algorithm: equivalent control method. Automatica 49, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2012.09.008 (2013).

Yu, X. H. & Wang, Z. B. Discretization effect on equivalent control-based multi-input sliding-mode control systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 53, 1563–1569. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.2008.928311 (2008).

Lee, H. & Utkin, V. I. Chattering suppression methods in sliding mode control systems. Annu. Rev. Control. 31, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcontrol.2007.08.001 (2007).

Edwards, C. & Shtessel, Y. B. Adaptive continuous higher order sliding mode control. Automatica 65, 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2015.11.038 (2016).

Bohner, M. & Guseinov, G. S. Improper integrals on time scales. Dyn. Syst. Appl. 12, 45–66 (2003).

Edwards, C. & Shtessel, Y. B. Adaptive continuous higher order sliding mode control. Automatica 65, 183–190 (2006).

Espitia, N. & Polyakov, A. Boundary time-varying feedbacks for ffxed-time stabilization of constantparameter reaction-diffusion systems. Automatica 103, 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2019.02.013 (2019).

Zhou, B. Finite-time stability analysis and stabilization by bounded linear time-varying feedback. Automatica 121, 109191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2020.109191 (2020).

Lee, H. & Utkin, V. I. Chattering suppression methods in sliding mode control systems. Annual Reviews inControl 31, 179–188 (2007).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing-Original Draft Preparation, Data Acquisition, Fangfang Zhou, Qi An and Yuhang He; Supervision, Writing-Review and Editing, Mengyue He and Jun Pan. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Te authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, F., An, Q., He, Y. et al. Prescribed time adaptive periodic sliding mode control of unmanned surface vehicle cluster under singular disturbance. Sci Rep 15, 19483 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95695-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95695-3