Abstract

This paper presents a comprehensive analysis of the indirect control of inertial properties of a rigid bodies system by semi-actively modifying the viscosity of tunable dampers. Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) optimal control logic and Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) analysis are employed to investigate its impact on the system response. The study utilizes a simple 2-d.o.f. architecture, referred to as the Toy Model, to demonstrate how proper selection of the damping coefficient allows for manipulation of the equivalent mass and variation of the natural frequency within a specific resonant band. Chirp excitations are applied to the Toy Model, and an iterative LQR scheme is implemented to optimally control the damping coefficient, thereby preventing resonance. Given that the adoption of the semi-active controller significantly alters the primary mass response, it is crucial to establish the cause-and-effect relationship between the control law and system response, which is achieved through the HHT. Notably, the proposed model is the first known example of a physical system that exhibits both intra- and inter-wave modulations of the instantaneous frequency of the main mass response, leading to a meta-phenomenon here defined as meta-frequency modulation. This meta-frequency modulation nonlinearly distorts the response of the optimally controlled system compared to passive optimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vibration isolation systems are widely investigated in research in many different fields. Vibration control systems can be passive, active, and semi-active. Semi-active control strategies are the most appealing due to their best compromise between performances and energy consumption required to modify the system parameters. Sound as the argument is, it should be noticed that the adoption of the semi-active controller strongly modifies the system response. Nevertheless, the cause-and-effect relationship between the control law and the induced response is often obscure. In this field, a special kind of time–frequency analysis is here implemented to unveil the hidden features of the control logic buried into the system response.

Damping and stiffness are the key objects of semi-active control algorithms and the main control solutions, which can be found in literature, are based on the use of smart TMD systems. In their basic form, TMD devices are sensitive to frequency deviation. Thus, they do not provide good performances over a wide range of frequency excitation, being generally tuned to the natural frequency of the primary system, which may be different due to the presence of disturbances, uncertainties, damages and so on. For this reason, the use of control strategies, mostly semi-active1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, has been largely explored. Depending on the nature of the excitation and resonant conditions of a system, the parameters of smart TMDs can be semi-actively varied to mitigate the system amplitude response. The great majority of research works propose either purely variable-damping TMDs11,12,13, or solely variable-stiffness TMDs14,15,16 systems, or architectures where the semi-active controllability of both parameters is achieved17,18,19,20.

The other parameter, i.e. the inertia, is something rarely explored. In fact, its active or semi-active modification is particularly challenging, since its value is normally prescribed on a design level. Notwithstanding, semi-active controllers seem to be preferred to indirectly change the system inertia, and their applications can be especially found in civil engineering. Shi et al.21 proposed a Self-Adjustable Variable Mass TMD (SAVM-TMD), capable of varying its mass and retuning its frequency based on the acceleration ratio between the primary system and the TMD. The application of such a device is considered for controlling human-induced vibrations of footbridges, where it showed excellent performances. Similarly, Wang et al.22 proposed a Semi-Active Independent Variable Mass TMD (SAIVM-TMD) to control pedestrian induced vibrations of pedestrian bridges. The mass of SAIVM-TMD is adjusted according to the structural IF by using the WT. A comparison with a passive TMD optimized for a pedestrian bridge under moving load is considered. The results show the best performance of the SAIVM-TMD being able to efficiently track the structural vibrational frequency changes.

A commonly employed strategy in structural vibration control is to address the identification of the IF of the system response as an additional input provided to the controller. This would guarantee the resetting of the stiffness and damping characteristics of the absorbers, enhancing their effectiveness in mitigating vibrations. Nagarajaiah23 analysed systems equipped with Smart TMDs (STMD) subjected to stationary and nonstationary excitations, where the tuning process of such smart absorbers was obtained through the identification of the structure IF, based on time–frequency methods, such as EMD, HT and STFT. Hemmati et al.19 developed a model for offshore wind turbine systems equipped with a semi-active time variant TMD, whose frequency could be retuned by applying the STFT to catch the changes in the IF of the system, due to soil and tower damages caused by earthquake strokes. Wang et al.13 proposed in their study a novel TMD system defined Semi-Active Eddy Current Pendulum TMD (SAEC-PTMD) able to retune its frequency and damping to the IF of the primary structure, identified through the HHT.

This paper investigates a novel approach for controlling the vibrational response of a rigid body system by indirectly modifying its equivalent mass, building upon the intriguing insights from previous studies. Indeed, this work aims to show how the inertial characteristics of a system can be effectively varied by adopting a semi-active control strategy capable of adjusting the damping coefficients of specific tunable dampers within a structure. This approach introduces a novel concept, where inertia control is achieved through variations in damping characteristics, eliminating the need for direct inertia modifications. To investigate the cause-and-effect relationship between control law and induced response, this paper utilizes the HHT. The main findings of the study are twofold: firstly, the proposed semi-active control optimizes the system response, and secondly, the time–frequency analysis sheds light on the underlying mechanisms by which the system response is influenced through the applied control strategy.

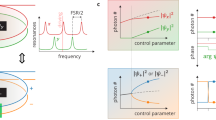

A simplified architecture, referred to as the Toy Model, is introduced. This model comprises a main mass connected to the frame through a spring and incorporates an auxiliary small mass-damper device. The damping coefficient of this device is optimized depending on the load conditions experienced by the system. The Toy Model architecture shows two degrees of freedom, but it exhibits a single natural frequency, which depends upon its equivalent mass. The equivalent mass, in turn, relies on the damping coefficient adjustment. By varying this parameter across a spectrum, the current natural frequency of the system can be effectively modified within a specified range to prevent resonance. Moreover, by employing the FDCM24 or the TF of the system, the determination of the resonant frequency dependence on damping is achieved.

An iterative LQR algorithm25,26 is derived to dynamically control the damping coefficient under various load scenarios, and a comparison is made with an optimized passive solution. The current resonant frequency of the system is determined based on the current optimal damping coefficient. However, due to the significant impact of the semi-active controller on the system response, the cause-and-effect relationship between control law and induced response remains unclear. To unravel the concealed features of the control logic embedded in the system response, the HHT27,28 is applied. This analysis reveals three noteworthy effects resulting from the optimal control scheme: (i) inter-wave frequency modulation of the main mass displacement, primarily induced by the external chirp load, irrespective of the control law; (ii) intra-wave frequency modulation, which arises from the optimal damping control law that effectively counterbalances the external force, causing substantial waveform distortion within each oscillation cycle; (iii) an intriguing meta-frequency modulation emerges from the blending of the aforementioned effects, where two distinct time scales coexist simultaneously.

The paper is structured as follows: in Section "Control of inertial properties and natural frequencies of a rigid bodies system by semi-active dampers", the authors describe a method for indirectly controlling the inertial properties and natural frequencies of rigid body systems through the semi-active control of viscous damping in tunable dampers. Initially, the Toy Model architecture is introduced to convey the fundamental idea, followed by an outline of a more general theory. Section "LQR control for a chirp external force" focuses on the application of LQR semi-active control of the damping coefficient of the Toy Model system under a chirp external force. The results of the optimal control are then compared to those of an optimized passive setting when the system is in resonant conditions. In Section "Time–frequency analysis", a time–frequency interpretation of the results obtained in Section "LQR control for a chirp external force" is performed to investigate the cause-and-effect relationship between control laws and induced system response. Section "Future experimental validation" describes the necessary experimental setup and flowchart to test and validate the theoretical predictions and simulation results of the study. Finally, Section "Conclusions" offers perspectives on the work and draws conclusions based on the findings.

Control of inertial properties and natural frequencies of a rigid bodies system by semi-active dampers

In this work the inertial properties and natural frequencies modification of a rigid bodies system through the semi-active control of the damping coefficients that characterize the tunable dampers is explored.

The Toy Model architecture

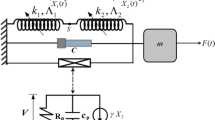

The possibility to indirectly control the equivalent mass of a rigid bodies system by the semi-active damping control is tackled by the usage of an elemental architecture, defined as the Toy Model, which is represented in the figure below:

It consists of a primary mass \(M\) restrained to the frame through a spring with stiffness \(k\) and a small auxiliary mass \(m\) attached to \(M\) through a tunable damper of damping coefficient \(c\left( t \right)\).

This system represents probably the simplest structure to show how the indirect control of the damping coefficient affects the equivalent mass \(m_{eq}\) of a system. Due to the its inertial characteristics variation, the natural frequency \(f_{n}\) changes as a consequence. In fact, by making \(c\left( t \right)\) vary between two extreme values \(\left[ {0, + \infty } \right]\), it holds:

which means the natural frequency of the system moves within a specific interval:

In the second case (\(c \to + \infty\)), the damper becomes so stiff that the system behaves as the two masses were rigidly attached to each other, causing the system to possess a unique total mass that is the sum of the two.

General theory

To outline the general theory that demonstrates how damping modifies the equivalent mass, or inertia, of a system, let’s start by reconsidering the Toy Model architecture (see Fig. 1).

The associated equations of motion are:

By differentiating with respect to time the second equation in Eq. (4), one obtains:

Now, by substituting into Eq. (5) the expression of \(\ddot{x}_{2}\) derived from the second equation in Eq. (4), and then, by isolating \(\dot{x}_{1}\), one obtains:

By substituting Eq. (6) into the first equation of system in Eq. (4), it becomes:

that can be read as:

with:

The Eq. (7) can be seen as the equation of an equivalent system which has an equivalent mass equal to:

which consists of two terms: a constant contribution, represented by \(M\), and an additional inertial term that considers the small auxiliary mass value \(m\) multiplied by a second coefficient, which mainly depends on damping and is here defined as mass amplification coefficient.

Moreover, Eq. (10) describes the change in the equivalent mass of the system for a generic setting of the damping coefficient. In the two extreme cases, i.e. for \(c \to 0\) and \(c \to + \infty\), it is straightforward to prove that it provides, respectively, \(m_{{eq_{0} }} = M\) and \(m_{{eq_{\infty } }} = M + m\), confirming so what previously discussed in Eq. (1)-(2). In addition, the current natural frequency change within the band \(f_{{n_{\infty } }} \le f_{n} \le f_{{n_{0} }}\) is achieved, as already observed in Eq. (3).

Furthermore, an interesting aspect emerges. Due to the presence of the damping coefficient time derivative, the mass amplification coefficient could become negative in certain circumstances. This means that, depending on the working conditions, a negative mass effect would be provided for the vibrational system29,30.

In general, if more small auxiliary mass-damper devices are attached to the main mass, as represented in Fig. 2, the procedure would be similar and proceeds as follows.

If \(m_{2} , \ldots ,m_{N}\) are the small auxiliary masses attached to the primary mass \(M\), the system dynamics is written as:

By following the same reasoning done for the single-small auxiliary mass-damper case, one can say:

By adding together the equations in Eq. (12) and by isolating again \(\dot{x}_{1}\) in the resulting expression, it holds:

which, if substituted into the first equation of Eq. (11), it leads to:

with:

The term within the square brackets in Eq. (14), which multiplies \(\ddot{x}_{1}\), represents the equivalent mass of the equivalent system whose dynamics is described by the same equation. The additional inertia term here appears in a more complicated form. Despite that, it is possible to define a mass amplification coefficient, identified with the second contribution in square brackets of Eq. (14). Thus, as before, damping plays the key role in the modification of the inertia of the system.

As an effect, it could be proven that the current natural frequency of the system changes too, in an analogous way to that discussed for the previous 2-d.o.f. system in Eq. (4).

Eigenfrequency dependence on damping

In the case of interest, the Toy Model 2-d.o.f. system is modelled as: \(M = 2\) kg, \(m = 1\) kg, \(k = 600\) N m−1. When the damping coefficient is tuned to the extremes of the range \(\left\{ {0,10^{4} \left( { + \infty } \right)} \right\}\) N∙s∙m-1, its natural frequency behaves as:

so that the resonant frequency band is roughly 0.5 Hz.

The change of \(f_{n}\) within the predefined interval as function of the damping coefficient can be derived by considering Eq. (8), or, in the general case, by Eq. (14). However, this is not an easy task since this dependence is nonlinear and suffers the time variation of the damping coefficients.

An approximated behaviour can be obtained by passing through the eigenvalue problem. This can be solved by applying the so-called FDCM (see Appendix A) or, equivalently, through the TF of the system dynamics by performing the LT (for null initial conditions), simply as:

with \({\varvec{H}}\left( s \right)\) be the TF matrix. Therefore, the variation of the poles of \({\varvec{H}}\left( s \right)\) as functions of the damping coefficient matrix will provide the eigenfrequencies behavior in terms of different damping settings.

By following the procedure described in Appendix A and, in particular, by observing Fig. A.1, Fig. A.2, Fig. A.3 and Fig. A.4, it can be said that, in a free solution condition, the system response is a damped oscillatory motion for all the intermediate damping coefficient values between 0 and \(+ \infty\). On the other hand, at the extremes of the damping coefficient range the solutions coincide with undamped oscillatory motions.

The discussion can be detailed by observing Fig. 3. On top, it shows the solutions computed for different damping coefficient values, where a velocity initial condition equal to 1 m s−1 has been imposed for the primary mass \(M\). The subplot on bottom shows the corresponding IFs, obtained by performing the HHT (see Appendix B) of the system displacements over a period \(\tilde{t} = 5\) s. For each solution, the corresponding IF stays within the resonant frequency band and oscillates around a constant mean value that changes accordingly to the selected damping value. Furthermore, as previously stated, the solutions corresponding to the damping range extremes, i.e. for \(c = 0\) and \(c = + \infty\), represent undamped motions, while for all the intermediate settings the solutions are damped. This means there exists a specific damping coefficient value which provides the most damped oscillatory solution obtainable, i.e. the solution that would expire in the shortest amount of time.

For the system of interest, it can be demonstrated that this value belongs to the interval \(\left\{ {12,13} \right\}\) N s m−1. The exact value, defined as \(c_{opt}\), can be obtained by studying the FRF, or the TF, of the system: it is the value that minimizes the FRF amplitude \(\mu\)31, as represented in Fig. 4, where:

with \(X\) the amplitude response of the main mass \(M\), \(\overline{F}\) the amplitude of the external excitation, \(f_{{n_{0} }}\) the resonant frequency for \(c = 0\), \(\sigma\) the ratio between the exciting frequency \(f\) and \(f_{{n_{0} }}\), \(\xi\) the damping factor and \(\varepsilon\) the ratio between the two masses.

By observing Fig. 4, \(c_{opt}\) corresponds to a specific curve which exactly crosses the Node, i.e. the intersection between the curves \(\mu_{0} ,\mu_{\infty }\). These are obtained from Eq. (20), respectively, for \(c = 0\) and \(c = + \infty\), and have the following expressions:

By intersecting the two curves in Eq. (24)–(25) the coordinates of the Node can be found to be \(\left\{ {\sigma_{Node} , \mu_{Node} } \right\} \simeq \left\{ {\sqrt {\frac{2}{2 + \varepsilon }} , \frac{1}{{\left( {\frac{2}{2 + \varepsilon } - 1} \right)^{2} }}} \right\}\).

To successively determine the damping coefficient value that minimizes the FRF, one has to guarantee that the first derivative of \(\mu\) with respect to \(\sigma\) is null at the Node, i.e.:

It can be shown that solving Eq. (26) provides \(c_{opt} \simeq 12.65\) N s m−1.

This damping value would produce an optimal passive solution. For this reason, the system response in case of damping coefficient \(c_{opt}\) will be considered as a reference to be compared with the optimal controlled solution provided by the application of the iterative LQR scheme (see Appendix C).

LQR control for a chirp external force

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed method, a chirp signal is applied on the Toy Model system as driving force. A chirp signal is a type of waveform characterized by a frequency that linearly increases or decreases with time. This unique feature allows for a continuous and smooth variation in frequency over a specific range. By utilizing a chirp signal, it becomes possible to examine the system response to a changing frequency stimulus, effectively testing the capabilities of the proposed method in handling dynamic and evolving load conditions. That frequency crosses the range defined by the two extreme resonant frequencies of the system, \(f_{{n_{0} }}\) and \(f_{{n_{\infty } }}\). Thus, it is interesting to confront the IF of the system response in respect of the IF of the chirp, to better understand how the control affects the IF of the system to reduce the amplitude response of the main mass \(M\).

The chirp excitation chosen for the analysis has the form \(F\left( t \right) = 5{\text{cos}}\left( {2\pi f_{0} t + \pi \Delta ft^{2} } \right)\) with \(f_{0} = 0.95f_{{n_{\infty } }}\) be the starting frequency at \(t = 0\) s, \(\Delta f = \frac{{f_{f} - f_{0} }}{{\tilde{t}}}\) the frequency slope and \(f_{f} = 1.05f_{{n_{0} }}\) the ending frequency at \(\tilde{t} = 10\) s, which is the observation time.

For the assigned chirp, its phase is: \(\varphi \left( t \right) = \left( {2\pi f_{0} + \pi \Delta ft} \right)t\). Since the chirp is already an IMF, namely it has a “well behaved” HT (see Appendix B), its instantaneous frequency can be evaluated from its analytic signal, which is \(z\left( t \right) = 5e^{\varphi \left( t \right)}\), by taking the time derivative of its phase: \(\omega \left( t \right) = \frac{d\varphi \left( t \right)}{{dt}} = 2\pi f_{0} + 2\pi \Delta ft = \omega_{0} + \Delta \omega t\).

The state vector of the system in Eq. (4) is \({\varvec{x}} = \left[ {x_{1} x_{2} \dot{x}_{1} \dot{x}_{2} } \right]^{T}\), while \({\varvec{x}}_{r} = \left[ {0 x_{2} 0 \dot{x}_{2} } \right]^{T}\) is the target state vector. The set of admissible values for the optimal damping coefficient is established to be \(\left[ {0, 10^{3} } \right]\) N∙s∙m-1. In addition, two different controlled solutions will be considered depending on the weights imposed for the cost matrix \(\overline{\user2{Q}}\) (see Appendix C). In case the diagonal terms of \(\overline{\user2{Q}}\) are set as \(\left[ {10^{9} ,1,10^{9} ,1} \right]\) the solution will be labelled as LQRlow; in case they are set as \(\left[ {10^{18} ,1,10^{18} ,1} \right]\) the solution will be labelled as LQRhigh.

Simulation results

Figure 5 illustrates the displacements and velocities of the main mass \(M\) (on the left) and the auxiliary mass \(m\) (on the right) caused by the chirp load application. A comparison between the controlled LQRlow and LQRhigh strategies, the optimized passive damper (\(c_{opt}\)) response and a non-optimized passive setting solution (\(c = 5\) N s m−1) is depicted. It reveals that the main mass exhibits smaller displacements in both controlled cases. Notably, the key distinction lies in the initial transient phase, where the LQRhigh displacement manifests the shortest rise time. Conversely, LQRlow exhibits a longer rise time with the highest amplitude during the transient phase but later settles to lower values during the stationary phase. In contrast, while the optimized passive system displays a longer rise time with displacement amplitude values falling between the previous two cases, the non-optimized solution manifests a resonant behavior. By using an optimization algorithm it would be possible to find out the best compromise between the LQRlow and LQRhigh settings, however this goes beyond the scope of the paper.

To further investigate the comparison between the semi-active and passive systems in terms of displacement amplitudes, the analysis in Fig. 6 is focused specifically on the resonant band of the system.

By observing the Figs. 5 and 6, it is clear that, without any control action, the system exhibits significantly higher displacement amplitudes within the resonant band, indicating a stronger susceptibility to resonance.

On the other hand, the optimized passive control, while reducing the amplitude compared to the unoptimized system, it is less effective than the LQR controller in attenuating vibrations. Here, the LQRlow control results in a moderate reduction in displacement amplitudes, being particularly effective during the stationary phase, although it produces a higher amplitude during the transient phase; the LQRhigh strategy demonstrates the most significant reduction in displacement amplitudes, particularly effective in minimizing the rise time during the initial transient phase.

By comparing these responses, both LQR control strategies (LQRlow and LQRhigh) outperform the optimized passive control, particularly in reducing the amplitude of vibrations within the resonant band. The inclusion of the uncontrolled response further underscores the necessity and effectiveness of the proposed control methods.

Figure 7 depicts the temporal dynamics of the optimal damping coefficient for the LQRlow and LQRhigh control laws. In both scenarios exhibit rapid on–off variations between the extremes of the predefined saturation interval. Although they share similar characteristics, the damping coefficient behavior associated with the high setting demonstrates a smoother trend. While the LQRlow control exhibits a more intricate pattern, the LQRhigh solution corresponds to a pure bang-bang control strategy.

Further analysis of the TF of the system uncovers the relationship between the current resonant frequency and the corresponding damping coefficient. Leveraging the LT (under null initial conditions), the following relationship is observed:

and the TF matrix is:

The system resonant frequency comes out by imposing \(\det \left( {{\varvec{H}}^{\user2{*}} \left( s \right)} \right) = 0\), which leads to:

The solution of the Eq. (30) provides the 3 poles of the TF. To understand their behaviour, it is sufficient to estimate their values for the optimal damping laws found by the LQR controllers, as shown in Fig. 8, neglecting the symbolic relationship between the poles and the damping coefficient itself.

Being the I pole real, it does not contribute to the computation of the system resonant frequency. II and III poles, on the other hand, result to be conjugate complexes, and possess an imaginary part which contains information about the current resonant frequency. As it can be seen in Fig. 9, this value continuously jumps between \(f_{{n_{\infty } }}\) and \(f_{{n_{0} }}\) because of the almost bang-bang control of \(c\left( t \right)\) (see Fig. 7).

The change in the equivalent mass \(m_{eq}\) of the system could be computed through Eq. (10), or, in a simpler form, as:

This means \(m_{eq}\) suddenly fluctuate between \(m_{{eq_{0} }} = M\) and \(m_{{eq_{\infty } }} = M + m\), as one could expect.

Looking at the periodic patterns of the control damping coefficient, seen in Fig. 7, they appear to be marked by a specific characteristic frequency: the control frequency \(\zeta\). In particular, inspecting the periodicity of the square waves reported in Fig. 7 and comparing it with the IFext,th of the chirp and the current resonant frequency of the Toy Model, it can be noticed how \(\zeta\) follows the slope of IFext,th and almost doubles it (see Fig. 10). In fact, by defining \(r\) as:

it emerges how this ratio is maintained around the value of \(2\), as shown in Fig. 11.

To sum up, the controller periodically changes the current system resonant frequency with a frequency \(\zeta\) that doubles the current chirp exciting frequency. This phenomenon belongs to the so-called parametric resonance phenomena32.

Time–frequency analysis

The effectiveness of the optimal control in attenuating the system response has been demonstrated. However, the cause-and-effect relationship between control laws and induced responses remains unclear at this stage. To address this point, a specific type of Time–Frequency analysis called the HHT is employed. This analysis aims to reveal the concealed features of the control logic embedded within the system response, providing a deeper understanding of the underlying dynamics. The HHT technique is particularly suited for this research as it excels at unveiling the hidden features of complex and non-stationary signals. By decomposing the system response into individual IMFs using EMD, the HHT method enables the identification and analysis of underlying processes operating at different timescales. Through this analysis, the HHT provides valuable insights into the distinct temporal and frequency characteristics of the system response influenced by the control logic.

Control damping coefficient

EMD (see Appendix B for details) is performed on the control damping coefficient laws of Fig. 7 to characterize their time frequency features.

Figure 12 shows the first three and most energetic IMFs and the corresponding IFs obtained applying the HHT to the optimal damping coefficient obtained with the LQRlow setting. By comparing the IFs with the IFext,th, it emerges that the third IMF exhibits an IF that is twice the IFext,th, confirming what afore discussed about the parameter \(r\) (see Fig. 11). The second and first IMFs, instead, manifest a high frequency content, being characterized by multiples of the IFext,th.

Considering then the optimal damping coefficient obtained through the LQRhigh setting (see Fig. 13), it can be observed that the third IMF exhibits an IF that doubles the IFext,th, as before. Again, the second and first IMFs show a higher frequency content characterized by multiples of the IFext,th, even if values are different with respect to the previous case.

Damping force

The time–frequency behaviour of the damping force is here examined. For this purpose, the Toy Model 2-d.o.f. system introduced in Subsect. "The Toy Model architecture" is considered again (see Fig. 1). It is important to note that the auxiliary mass-damper and stiffness are intentionally selected to ensure that the elastic force exerted by the absorber on the primary mass precisely counteracts the external harmonic force. With this consideration in mind, it is expected that both the passive and semi-active damping forces acting on the main mass will strive to effectively balance the external force and minimize the overall displacement.

The damping force coming from the optimized passive setting is \(F_{d} = c_{opt} \left( {\dot{x}_{1} - \dot{x}_{2} } \right)\), while for the controlled cases it is \(F_{d} = u\left( t \right)\left( {\dot{x}_{1} - \dot{x}_{2} } \right)\). The corresponding trends are portrayed in Fig. 14.

Figure 15 showcases the fundamental IMF and the corresponding IF of the damping force for the optimized passive setting, obtained through the application of the HHT. The optimized passive setting reveals a damped harmonic motion in the damping force, with an instantaneous frequency matching that of the external force. This observation confirms that the passive setting functions akin to a dynamic vibration absorber, effectively minimizing the displacement of the main mass.

The time behaviours of the semi-active damping forces can be quite intricate. To elucidate their main characteristics, we will now concentrate on the LQRlow type. In Fig. 16, we observe the IMFs and their corresponding IFs for the corresponding damping force. The figure displays several IMFs, with the first four being the most significant ones. Particularly, IMF4,Fd, stands out as the most energetic component. Interestingly, its IF closely aligns with IFext,th, showing similar features to the signal in Fig. 15 derived from the passive setting. Notably, this IMF is responsible for the damped harmonic trend, which gives rise to the extrema of the force in the second subplot of Fig. 14: the force and IMF4,Fd have the same envelopes. The other three IMFs cause deformation in the main waveform of the force and are characterized by considerably higher frequencies. This reflects the high-frequency content present in the optimal damping coefficient.

Figure 17 displays the IMFs and their corresponding IFs for the control damping force obtained using the LQRhigh scheme. As anticipated in Fig. 7, the LQRhigh acts like a bang-bang controller, resulting in a force consisting of a train of pulses that are challenging to decompose using the EMD algorithm (see Appendix B). This difficulty arises due to the EMD’s sifting process, which generates intrinsic oscillatory modes based on characteristic time scales identified empirically in the data, enabling its decomposition.

However, the signal from the LQRhigh scheme presents a specific issue. The alternating local maxima, zero crossings, and minima are extremely sharp, lacking any sensible undulation between them. This sharpness is evident in the third subplot of Fig. 14.

As a result, there is no characteristic scale in the data that can be effectively sifted out by the EMD algorithm. When applying EMD to this signal, several IMFs are generated, but they lack physical meaning. Each IMF exhibits spurious undulations coinciding with the extrema of the signal, arising during the decomposition process. The method utilizes envelopes defined by the local maxima and minima separately: cubic spline lines connect all the local maxima to form the upper envelope and similarly for the local minima to create the lower envelope. The mean envelope is then computed and subtracted from the original signal, and this process continues. However, being the envelopes much smoother than the original signal, spurious undulations emerge, inaccurately extracted from the original signal.

A different, still not entirely physically meaningful, time–frequency representation of the signal is obtained with the Morlet WT, as shown in Fig. 18. The spectrogram is characterized by V-shaped highly correlated regions around the extrema of the signal, giving the misleading impression that, during those time intervals, a wide range of frequencies is involved. This occurs because the signal is composed of a train of pulses that suddenly vanish outside the location of the extrema within a certain time interval.

The nullity of its values is correctly but artificially obtained by the wavelet transformation, which is based on Fourier analysis. This nullity results from an infinite superposition of virtual waves that interfere to annihilate each other. In the time domain, where the signal vanishes, it is artificially perceived as dynamic due to the existence of interfering waves. This perception contrasts with a proper understanding of the physical situation where the signal does not exist.

To summarize, when the external force is a chirp of mean frequency equal to the natural frequency of the main mass, the passive and semi-active settings act like dynamic vibration absorbers. However, the semi-active settings are more effective at minimizing the displacement of the main mass because the control laws produce more extended time–frequency forces that can better counterbalance the unsteady one externally applied.

Main mass response

Figure 19 shows the IMF and the related IF obtained through the HHT (see Appendix B) for the displacement of the main mass in the optimized passive setting case. Since the original signal is already an IMF, the application of the EMD produces only one IMF, that is very close to the signal itself. Its IF linearly increases with time and, almost, coincides with the one of the driving force \(\omega \left( t \right) = \omega_{0} + \Delta \omega t\).

Figure 20 displays the IMF and the corresponding IF resulting from the application of the HHT to the displacement of the main mass when the LQRlow control is implemented. Upon initial observation, the IMF may appear like the one shown in Fig. 19. However, it is noteworthy that the semi-active controller significantly modifies the response of the main mass, leading to the emergence of nonlinear features. Specifically, this wave exhibits harmonic distortion akin to the Stokes wave27, characterized by sharpened crests and rounded-off troughs due to intra-wave frequency modulations. Additionally, inter-wave frequency modulations, which were already evident in Fig. 19 for the passive setting, are also present.

To provide a more comprehensive understanding of these concepts, we present a coarse, yet meaningful approximation of the signal represented by the analytical model wave, given by the following equation:

where \(\omega \left( t \right) = \omega_{0} + \Delta \omega t\) is the instantaneous frequency of the chirp excitation defined in Sect. "LQR control for a chirp external force", \(A\) and \(\varepsilon\) are suitable amplitudes parameters with \(\varepsilon\) small, i.e. < < 1 (note that this function is related to the solution of the nonlinear wave equation: \(\frac{{d^{2} x\left( t \right)}}{{dt^{2} }} + \left( {\tilde{\omega } + \varepsilon \tilde{\omega }\cos \left( {\tilde{\omega }t} \right)} \right)^{2} x\left( t \right) - \varepsilon \tilde{\omega }^{2} {\text{sin }}\left( {\tilde{\omega }t} \right)\sqrt {1 - x^{2} \left( t \right)} = 0\), with \(\tilde{\omega }\) constant).

The function \(x\left( t \right)\) is clearly a frequency modulated wave, since \(x\left( t \right)\) is already an IMF (see Fig. 21 for the comparison in case \(A = 0.05, \varepsilon = 0.1\)), the nonlinear phase \(\varphi \left( t \right)\) and the instantaneous frequency \(\Omega \left( t \right)\) are readily obtained from its analytic signal in Eq. (33):

Then, by substituting \(\omega \left( t \right) = \omega_{0} + \Delta \omega t\) in Eq. (35), it holds:

In particular, by defining with \(\omega_{2} \left( t \right) = \omega_{0} + 2\Delta \omega t = 2\omega \left( t \right) - \omega_{0}\) (note that \(\omega_{2} \left( t \right)\) has twice the slope of \(\omega \left( t \right)\)) and by substituting it into Eq. (36), it finally holds:

With reference to the Fig. 22, \(\Omega \left( t \right)\) is a nonlinear function of the time, which has the following features:

-

i.

The function \(\omega_{2} \left( t \right)\) is the amplitude modulating function, that slowly increases with time. If \(\omega_{2}\) were constant, the mean value of \(\Omega \left( t \right)\) would be \(\omega_{2}\);

-

ii.

Since \(\omega_{2} \left( t \right)\) becomes higher and higher, the waveform undergoes gradual modifications, resulting in what is referred to as inter-wave frequency modulation. This modulation occurs cycle after cycle, characterized by a gentle variation. In our example the time scale of the inter-wave frequency modulation is given by \(2\pi /\left( {\frac{{d\omega_{2} \left( t \right)}}{dt}dt} \right) \approx 2\pi /\Delta \omega\);

-

iii.

The function \(\left( {1 + \varepsilon {\text{cos }}\left( {\omega \left( t \right)t} \right)} \right)\) is a nonlinear function of the time, in first approximation can be thought as an “almost” periodic function with pseudo-period 2 \(\pi /\omega \left( t \right)\);

-

iv.

Due to iii., the waveform \(x\left( t \right)\) is almost periodic and experiences strong modulation within each period 2 \(\pi /\omega \left( t \right)\). This characteristic is referred to as intra-wave frequency modulation, highlighting the significant variation within each cycle;

-

v.

It is important to emphasize that, to the authors’ knowledge27,28, this is the first example of a physical system simultaneously exhibiting intra- and inter-wave frequency modulations. In the existing literature, these two effects were introduced separately for different signals. For instance, the Stokes wave displays intra-wave modulation characterized by an instantaneous frequency \(\tilde{\omega }\left( {1 + \varepsilon {\text{cos }}\left( {\tilde{\omega }t} \right)} \right)\), with \(\tilde{\omega }\) constant, and chirp-function for inter-wave modulation, characterized by an instantaneous frequency that linearly increases with time. The coexistence of intra- and inter-wave frequency modulations gives rise to a meta-phenomenon, here named meta-frequency modulation, arising from the blending of the previous features. With reference to the point iii, the intra-wave frequency modulation is characterised by the pseudo-period \(2\pi /\omega \left( t \right),\) which becomes progressively shorter due to the linear variability of \(\omega \left( t \right)\). This same variability causes the inter-wave frequency modulation discussed in point ii. Therefore, two different time scales, \(2\pi /\omega \left( t \right)\) and \(2\pi /\Delta \omega\), are simultaneously present, significantly modifying the waveform through this meta-frequency modulation.

When the LQRhigh control is applied, Fig. 23 illustrates the IMF and IF of the main mass displacement obtained for this control setting. The signal qualitative features resemble those observed in Fig. 20. However, when compared to the IMF obtained for the LQRlow scheme, the intra-wave frequency modulation becomes more pronounced, resulting in significantly distorted waves within each period of oscillation.

In summary, the application of the optimal control scheme reveals three notable effects. Firstly, there is inter-wave frequency modulation of the main mass displacement, which is primarily induced by the external chirp regardless of the control law. Secondly, an intra-wave frequency modulation arises due to the optimal damping control law for the semi-active setting, which, while counterbalancing the external force, causes substantial waveform distortion within each oscillation cycle. Most notably, an undiscovered meta-frequency modulation emerges, resulting from the blending of the aforementioned features. This meta-frequency modulation involves the coexistence of two distinct time scales, \(2\pi /\omega \left( t \right)\) and \(2\pi /\Delta \omega\), simultaneously shaping the signal.

Future experimental validation

This section outlines the experimental plan for validating the proposed control methodology. A scaled-down physical model will be constructed to replicate the 2-degree-of-freedom system described in the study, comprising a primary mass connected to a base by a spring and a small auxiliary mass attached to the primary mass via a tunable damper. The tunable dampers will be implemented using magnetorheological (MR) or piezoelectric dampers, whose damping coefficients can be adjusted in real time through an external control system.

To enable real-time control, an LQR controller will be designed and implemented on a digital signal processor (DSP) or a real-time control platform such as dSPACE. This widely used system supports the development and real-time execution of control algorithms, making it ideal for the experimental setup, as shown in Fig. 24.

The controller will regulate the damping coefficients based on sensor feedback while a chirp signal generator applies a variable-frequency excitation force. This excitation will span a range of frequencies that includes the system’s natural frequencies, as predicted by the theoretical model.

Measurement instruments (e.g., accelerometers and laser displacement sensors) will capture the response of both the primary and auxiliary masses. The collected data will then be analysed to determine the instantaneous frequency and amplitude of the system’s response. The experimental procedure, described in Fig. 25, begins with baseline measurements of the natural frequency and damping characteristics in the absence of active control, serving as a reference point. Subsequently, the LQR control system will be activated, and the damping coefficients will be adjusted in real time to minimize the primary mass response. System performance under different control settings, such as LQRlow and LQRhigh, will be recorded.

Data analysis will employ the HHT to investigate intra- and inter-wave frequency modulations and the resulting meta-frequency modulation in the system’s response. These findings will be compared with theoretical predictions, thereby validating the proposed model.

The expected outcomes include demonstrating the effectiveness of the LQR control strategy in reducing the primary mass response and experimentally confirming the existence of intra- and inter-wave frequency modulations—thereby validating the phenomenon of meta-frequency modulation. This physical evidence will underscore the potential practical applications of the control method in various engineering fields.

Additionally, systematic testing under diverse loading scenarios (e.g., harmonic and random excitations) is planned to further assess the robustness of the control methodology. Comparative evaluations of MR versus piezoelectric dampers will be conducted, focusing on response time, power consumption, and overall control accuracy. These investigations will refine the real-time control algorithm, ensuring that the proposed approach remains both effective and adaptable across a wide range of engineering applications.

By conducting this comprehensive experimental validation, the authors aim to substantiate the theoretical advancements presented in this study and demonstrate the practical feasibility of the proposed methodology—thereby paving the way for future research and applications in fields such as civil engineering, renewable energy, aerospace, robotics, and medical devices.

Finally, the semi-active control strategy leverages current state-of-the-art technologies: integrating MR or piezoelectric dampers with modern real-time control platforms offers a robust and viable route for implementation. These devices are already well-established in engineering sectors—including civil, aerospace, robotics, and renewable energy—highlighting the practical relevance of this approach. Coupled with an LQR-based control algorithm, the system can adapt its damping characteristics in real time, directly influencing inertial properties and improving the overall vibrational performance of the structure.

Conclusions

This paper demonstrates how tunable dampers, managed through a Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR), can indirectly control the inertial properties of a rigid body system and mitigate resonance under chirp excitation. The adoption of a simple 2-degree-of-freedom (2-d.o.f.) model shows that proper adjustment of the damping coefficient enables manipulation of the equivalent mass and natural frequency, effectively minimizing the response of the master mass.

The key contributions are twofold: (i) the introduction of a novel semi-active control strategy that adjusts inertial properties via LQR-driven tunable dampers; and (ii) the physical interpretation of the induced system response through the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT), clarifying the cause-and-effect link between the control law and observed dynamics. Notably, the system exhibits a previously unreported meta-frequency modulation, arising from simultaneous intra- and inter-wave frequency shifts.

These findings have broad potential applications in Civil Engineering (seismic and traffic load responses), Renewable Energy (offshore wind turbines), Aerospace (vibration control in flight), Robotics (precision and stability), and Medical Devices (prosthetics and biomechanical implants). By enabling real-time tuning of inertial characteristics, the proposed approach offers a versatile means to enhance safety, efficiency, and resilience in diverse engineering systems.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. Please contact Simone Mesbahi, Ph.D., Sapienza University of Rome, via email at mesbahisimone94@gmail.com for access to the data.

Abbreviations

- EMD:

-

Empirical mode decomposition

- FDCM:

-

Frazer-duncan-collar’s method

- FRF:

-

Frequency response function

- FT:

-

Fourier transform

- HHT:

-

Hilbert-huang transform

- HT:

-

Hilbert transform

- IF:

-

Instantaneous frequency

- IMF:

-

Intrinsic (or Implicit) mode function

- LQR:

-

Linear quadratic regulator

- LT:

-

Laplace transform

- STFT:

-

Short-time fourier transform

- TF:

-

Transfer function

- TMD:

-

Tuned mass damper

- WT:

-

Wavelet transform

References

Liu, Y., Matsuhisa, H. & Utsuno, H. Semi-Active vibration isolation system with variable stiffness and damping control. J. Sound. Vib. 313(1–2), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2007.11.045 (2008).

Le, T. D. & Ahn, K. K. Experimental investigation of a vibration isolation system using negative stiffness structure. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 70, 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2013.02.009 (2013).

Miah, M. S., Chatzi, E. N. & Weber, F. Semi-active control for vibration mitigation of structural systems incorporating uncertainties. Smart Mater. Struct. 24, 055016. https://doi.org/10.1088/0964-1726/24/5/055016 (2015).

Wei, X., Zhu, M. & Jia, L. A semi-active control suspension system for railway vehicles with magnetorheological fluid dampers. Veh. Syst. Dyn. Int. J. Veh. Mech. Mobil. 54(7), 982–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114.2016.1177189 (2016).

Ata, W. G. & Salem, A. M. Semi-active control of tracked vehicle suspension incorporating magnetorheological dampers. Veh. Syst. Dyn. Int. J. Veh. Mech. Mobil. 55(5), 626–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114.2016.1273531 (2017).

Bozorgvar, M. & Zahrai, S. M. Semi-active seismic control of buildings using MR damper and adaptive neural-fuzzy intelligent controller optimized with genetic algorithm. J. Vib. Control 25(2), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546318774502 (2019).

Wang, C., Nie, H., Chen, J. & Lee, H. P. The design and dynamic analysis of a lunar lander with semi-active control. Acta Astronaut. 157, 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2018.12.037 (2019).

Wasilewski, M. & Pisarski, D. Adaptive semi-active control of a beam structure subjected to a moving load traversing with time-varying velocity. J. Sound. Vib. 481, 115404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2020.115404 (2020).

Yiwei, Z., Shaopu, Y., Yongqiang, L., Yingying, L. & Pengfei, L. A new semi-active control strategy and its application in railway vehicles, ICANDVC 2021: Advances in applied nonlinear dynamics. Vibrat. Control 799, 240–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5912-6_18 (2022).

Sadatieh, M. S. M. & Ghorbani-Tanha, A. K. An innovative semi-active pendulum tuned mass damper and its application in vibration control. J. Vib. Control 29(7–8), 1820–1832. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775463211070903 (2023).

Bathaei, A., Zahrai, S. M. & Ramezani, M. Semi-active seismic control of an 11-DOF building model with TMD+MR damper using type-1 and -2 fuzzy algorithms. J. Vib. Control 24(13), 2938–2953. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546317696369 (2017).

Salari, S., Hormozabad, S. J., Ghorbani-Tanha, A. K. & Rahimian, M. Innovative mobile TMD system for semi-active vibration control of inclined sagged cables. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 23, 641–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-018-0161-0 (2019).

Wang, L., Shi, W., Zhou, Y. & Zhang, Q. Semi-active eddy current pendulum tuned mass damper with variable frequency and damping. Smart Mater. Struct. 25(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.12989/sss.2020.25.1.065 (2020).

Lin, G., Lin, C., Chen, B. & Soong, T. Vibration control performance of tuned mass dampers with resettable variable stiffness. Eng. Struct. 83, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2014.10.041 (2015).

Gao, P., Xiang, C., Liu, H., Walker, P. & Zhang, N. Design of the frequency tuning scheme for a semi-active vibration absorber. Mech. Mach. Theory 140, 641–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2019.06.025 (2019).

Chakraborty, S., Ghosh, A. & Ray-Chaudhuri, S. A novel tuned mass-conical spring system for passive vibration control of a variable mass structure. J. Vib. Control 28(13–14), 1565–1579. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775463211000497 (2022).

Weber, F. Semi-active vibration absorber based on real-time controlled MR damper. Mech. Syst, Signal Process. 46(2), 272–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2014.01.017 (2014).

Sun, C. Semi-active control of monopile offshore wind turbines under multi-hazards. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 99, 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2017.06.016 (2018).

Hemmati, A. & Oterkus, E. Semi-active structural control of offshore wind turbines considering damage development. J. Marine Sci. Eng. 6(3), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse6030102 (2018).

Wang, L., Nagarajaiah, S., Shi, W. & Zhou, Y. Seismic performance improvement of base-isolated structures using a semi-active tuned mass damper. Eng. Struct. 271, 114963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.114963 (2022).

Shi, W., Wang, L. & Zheng, L. Study on self-adjustable tuned mass damper with variable mass. Struct. Control Health Monitor. 25(3), e2114. https://doi.org/10.1002/stc.2114 (2018).

Wang, L., Nagarajaiah, S., Shi, W. & Zhou, Y. Semi-active control of walking-induced vibrations in bridges using adaptive tuned mass damper considering human-structure-interaction. Eng. Struct. 244, 112743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.112743 (2021).

Nagarajaiah, S. Adaptive passive, semiactive, smart tuned mass dampers: identification and control using empirical mode decomposition, hilbert transform, and short-term fourier transform. Struct. Control Health Monitor. 16(7–8), 800–841. https://doi.org/10.1002/stc.349 (2009).

Frazer, R. A., Duncan, W. J. & Collar, A. R. Elementary matrices and some applications to dynamics and differential equations 1st edn. (Cambridge University Press, 1960).

Dorato, P., Abdallah, C. T. & Cerone, V. Linear quadratic control: An introduction (Krieger Pub. Co., 2000).

Anderson, B. D. O. & Moore, J. B. Optimal control: Linear quadratic methods (Dover Publications Inc., 2007).

Huang, N. E. et al. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 454(1971), 903–995. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1998.0193 (1998).

Kerschen, G., Vakakis, A. F., Lee, Y. S., McFarland, D. M. & Bergman, L. A. Toward a fundamental understanding of the Hilbert-Huang transform in nonlinear structural dynamics. J. Vib. Contr. 14(1–2), 77–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546307079381 (2008).

Huang, H. H., Sun, C. T. & Huang, G. L. On the negative effective mass density in acoustic metamaterials. Int. J. Eng. Sci 47(4), 610–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijengsci.2008.12.007 (2009).

Cveticanin, L., Zukovic, M. & Cveticanin, D. On the elastic metamaterial with negative effective mass. J. Sound Vib. 436, 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2018.06.066 (2018).

Jazar, R. N. Vehicle dynamics: Theory and application 3rd edn. (Springer, 2017).

Kovacic, I., Rand, R. H. & Sah, S. M. Mathieu’s equation and its generalizations: Overview of stability charts and their features. Appl. Mech. Rev. 70(2), 020802. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4039144 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by co-funding of the European Union - The National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) – Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4 - NextGeneration EU Project - Project "MOST-Sustainable Mobility Center” - CUP B83C22002900007. This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions, neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Carcaterra, N. Roveri, S. Mesbahi, S. Milana developed the theory behind the manuscript; A. Carcaterra, N. Roveri, S. Mesbahi, S. Milana contributed to the writing of the main manuscript; S. Mesbahi performed the analyses and provided associated results and figures; All authors contributed to the manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mesbahi, S., Roveri, N., Milana, S. et al. Meta-frequency modulation in LQR vibration control with chirp excitation. Sci Rep 15, 13145 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95958-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95958-z