Abstract

Depression is an important public health issue. Over the years, the consumption of antidepressants has increased in the population, which on one hand may mean increased diagnostic accuracy, but on the other could mean a problem of inappropriate consumption and prescribing. The aim of the study is to analyze trends in antidepressant consumption and major drug classes in Italy in the last 15 years to provide useful public health insights for policymakers. Data were collected from Osservasalute and OsMed reports from 2008 to 2022. We included the overall consumption of antidepressants and the three subclasses of the most widely used antidepressant drugs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Data were expressed as the daily defined dose (DDD) per 1,000 inhabitants. A joinpoint analysis was conducted for each data point in order to describe the trend and identify the Annual Percentage Change (APC) and the Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC). In Italy, there was an increase in antidepressant consumption of 36.7% over the period. Overall, Joinpoint analysis shows a significant AAPC of + 2.31%. Analyzing the subclasses also showed a significant increase in the consumption of SSRIs (AAPC = 1.46%) and SNRIs (AAPC = + 2.14%). In contrast, there was a significant decrease in the consumption of TCAs (AAPC = − 1.46%). The trend of antidepressant use has been increasing steadily over the considered period. Public Health plays a key role in proposing solutions to improve the mental health of the population. Targeted interventions must be carried out to raise awareness among policy makers, clinicians and the population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is a major public health issue, with a significant health and economic impact worldwide1,2, accounting for 1.95% of all Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) and for 6.22% of all Years Lived with a Disability (YLDs) in 20213. It is estimated that among mental disorders, depression is responsible for the largest proportion of both DALYs and YLDs globally4,5, with an increasing trend over the last 30 years5. Even in terms of prevalence and incidence, an increase of cases is observed, with nearly 300 million people suffering from it, (about 3.8% of the global population)6. Moreover, the World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that in 2030 depression will be the leading disease in terms of disability worldwide7. Considering the characteristics of the population, it is observed that depression is a disease that affects all age groups, albeit showing an increasing trend as age increases. In addition, females result more affected than males, both in terms of incidence and DALYs5. The direct and indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have further increased the risk factors for poor mental health and weakened many of the protective factors, leading to a significant deterioration in the mental health of the population, increasing the incidence of depressive disorders8. Although comparable data are still scarce, national estimates show that the prevalence of depressive symptoms during the pandemic in some cases doubled compared to pre-pandemic levels in several countries, including Italy8,9,10.

Antidepressants are a cornerstone in the pharmacological treatment of depression, as well as of many other mental health disorders, including anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder11. Their utilization patterns provide crucial insights into the management of depression within the population. It is important to conisder, however, that the prescription of such drugs should be based on a careful clinical analysis of the patient, considering not only the characteristics of the individual but also the level of depression. In fact, several studies have shown that the remission rate is extremely variable, with 50% and 70% of patients responding to antidepressant therapy but only 25-35% of patients experiencing full remission, or even less12. The use of antidepressant drugs has been steadily increasing in recent decades and has accelerated further since the introduction of SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors) in the early 1990s, and with it healthcare spending on this drug category13. Consequently, the consumption of these drugs is expected to increase in Italy consistently with the trends reported in many countries in the last two decades14,15,16,17,18,19.

Currenlty, depression is the most common mental disorder in Italy, with about 3 million people (6.4% of the population) reporting as suffering from it20 and thus representing an important public health issue, with an impact in terms of DALYs, and YLDs.

In this context, this study aims to update a previous analysis18, exploring the rates of consumption of antidepressants in the Italian population from 2008 to 2022 through the Joinpoint regression model.

Results

Overall consumption of antidepressants

The consumption of antidepressants in Italy increased from 2008 to 2022 (Table 1), with a steady but less pronounced rise in the period 2012–2016. Specifically, a year-on-year increase is observed, with values rising from 33.5 DDD/1,000 inhabitants in 2008 to 45.8 DDD/1,000 inhabitants in 2022, with an overall increase of 36.7%. The lowest change is observed between 2011 and 2012 (+ 0.3%), while the highest increase is reported between 2010 and 2011 (+ 7.8%). Considering the COVID-19 pandemic years, although the increase in antidepressant consumption was maintained, the rates were lower than those observed in the pre-pandemic period.

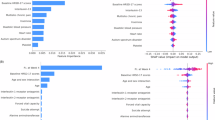

Regression analysis showed two joinpoints, which identify 3 trends over the study period (Fig. 1; Table 3). The first interval (2008–2011) showed a significant increase in antidepressant consumption (APC = + 4.77%, 95%CI: 3.68 to 5.88, p < 0.0001), followed by a non-significant increase between 2011 and 2016 (APC = + 0.80%, 95%CI: − 0.12 to 1.37, p = 0.08). In fact, an annual percentage increase of ≤ 1% is observed in this intereval, showing a sort of platau of the trend, albeit maintaining limited growth (Table 1). Finally, a significant increase is observed between 2016 and 2022 with APC of + 2.37% (95%CI: 2.00 to 3.29, p < 0.0001). Overall, there was an increasing trend, with an AAPC of + 2.31% (95%CI: 2.17–2.49%, p < 0.0001).

Consumption of antidepressants by class of medication

The consumption of SSRIs ranged from a low of 25.9 DDD/1,000 hinabitants in 2008 to a high of 31.7 DDD/1,000 hinabitants in 2022 (Table 2). Overall, an increase of 22.4% is observed over the period. Joinpoint analysis identified 3 intervals (Fig. 2; Table 3). A significant increase was observed from 2008 to 2013 (APC = + 2.59%, 95%CI: 2.17 to 3.10, p < 0.0001), followed by a decrease until 2017 (APC = − 0.23%, 95%CI: 0.98 to 0.36, p = 0.36). Finally, a significant increase is observed from 2017 to 2022 (APC = + 1.71%, 95%CI: 1.34 to 2.39, p < 0.0001). Overall, an increasing trend was reported, with an AAPC of + 1.46% (95%CI: 1.35–1.58%, p < 0.0001).

SNRIs consumption showed a steady increase between 2013 and 2022, rising from 6.0 DDD/1,000 hinabitants to 7.3 DDD/1,000 hinabitants (+ 21.7%) (Table 2). The analysis highlighted one joinpoints (Fig. 3; Table 3). The first interval, from 2013 to 2017, showed a significant increase in SNRIs consumption (APC = + 1.15%, 95%CI: 0.47 to 1.59, p = 0.007), which is followed by a further significant increase until 2022 (APC = + 2.94%, 95%CI: 2.61 to 3.42, p < 0.0001). Overall, there was an increasing trend, with an AAPC of + 2.14% (95%CI: 1.98–2.29%, p < 0.0001).

Consumption of TCAs showed a decrease over the period considered, with values remaining consistently < 2% (Table 2). The analysis showed a significant reduction in the consumption of TCAs in the absence of joinpoint, with AAPC thus coinciding with APC (− 1.46%, 95%CI: − 2.07 to − 0.65, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4; Table 3).

Discussion

Our study aimed to provide an aid to research in this field by assessing the trend in antidepressant usage in Italy from 2008 to 2022 using the most recent data available. In this sense, although other studies have analyzed the consumption of anidepressives over time and evaluated, in part, the impact of the pandemic21,22,23,24,25, our analysis is the first at the Italian level as well as considering a long period of time and including at least two years afeter the onset of the pandemic.

Overall, we observed a significant increase in the consumption of antidepressants in Italy between 2008 and 2022. By analyzing these patterns, we seek to better understand the scope and dynamics of antidepressant consumption in the Italian context, to provide input on mental health support and provision of funding to support the availability and use of specialist services in the National Health System (NHS), and thereby contributing to the ongoing efforts to improve mental health care and outcomes.

Our study reports similar results observed in other European and OECD countries, albeit with some differences. In particular, in past years an average rate of increase was observed in the EU the use of antidepressants increased on average by 19.83%, ranging from 3% in the Netherlands and Switzerland to 59% seen in Finland26. More recently, these trends have been confirmed, however, showing important variations among countries, which could therefore be related to several factors such as prescriptive appropriateness, improvements in accessibility to mental health services, and reduction of stigma about mental disorders27.

The increase in consumption could be related to aspects such as the high prevalence and low remission rates despite treatment with currently available antidepressants28,29. This finding coupled with the fact that the treatment is prescribed not only in acute cases and for short therapies but also in maintenance and relapse prevention, in line with scientific evidence indicating how in the USA 60% of people who start antidepressants treatment continue it for at least 2 years and 14% for 10 years30,31,32.

An Italian study monitored antidepressant consumption trends in Italy in the decade 2000–2011, observing a fourfold increase in consumption in the periodic reference range18. This trend reflects broader awareness and recognition of depressive disorders, as well as evolving guidelines and practices in mental healthcare. On the other hand, this class of drugs, being able to be prescribed by both specialists and general practitioners (GPs) and being fully reimbursed by the NHS might be often overprescribed or inappropriately prescribed. The appropriateness of a treatment is not always guaranteed33, as highlighted by a study focused on primary care in Italy, which showed an increase in the prevalence of antidepressant use in the absence of a parallel increase in incidence of the disease. This finding shows that in the Italian population antidepressants are often used intermittently, with short repeated cycles. This treatment pattern configures a picture characterized by many arbitrary and premature interruptions of therapy, often decided independently, or otherwise inappropriately that lead to chronicity of the pathology and therefore of the treatment34.

The growing awareness of depression as an important public health issue over the past decade has also coincided with the arrival of several new classes of antidepressants that have increased pharmacological treatment options for depression, particularly in the elderly35. These new and more expensive antidepressant drugs, which have been shown to be effective36, contribute to the increase in the total cost of antidepressants37. Their use is not limited to the psychological field, as they are approved or otherwise commonly used for a wide variety of conditions such as fibromyalgia, migraine prevention, diabetic neuropathy, sleep disorders, and premature ejaculation38. This evidence may therefore confound the data on the use of these drugs, which does not refer exclusively to people with depression.

In order to reduce the burden of mental health diseases and to promote the appropriate prescribing of antidepressants, in Italy the National Action Plan for Mental Health (PANSM) was approved in 201339, identifing a number priorities on which to direct specific and differentiated regional and local projects, which provide for the implementation of treatment pathways for psychiatric disorders capable of intercepting the health demand of the general population. Adherence to these innovative diagnostic-therapeutic protocols, may have played a role in increasing diagnostic capacity, proper patient care, and prescription appropriateness. The implementation of this Plan may have in part contributed to the plateau shown between 2012 and 2016, in which there is a much smaller and nonsignificant increase in antidepressant use, with some classes showing an oscillating pattern alternating between increases and decreases in consumption.

Our analysis identified a significant increase in antidepressant consumption in 2017. As reported in the OsMed Report, in that year Central Nervous System drugs accounted for the sixth largest therapeutic category by public expenditure, amounting to nearly 1,866 million euros, and how the ranking of this category was justified by the expenditure resulting from the purchase of these drugs under contracted care40. Vortioxetine, a newly marketed antidepressant drug at the time, registered the largest increase in consumption over the previous year41. The molecule has a profile that suggests indication in the treatment of the elderly with depression and/or cognitive impairment41. Considering that the frequency of depressive disorder increases with age and that in the elderly it is often undertreated due to comorbidities and polypharmacotherapy42, the introduction of this new therapeutic option, could justify its increased prescription, in the year 2017, among the antidepressant category and thus be one of the possible reasons for the significant trend change found through our analysis.

In recent years, the upward trend in antidepressant use may have been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, such as as a result of social restriction and isolation, decreased quality of life, discontinuation of psychiatric interventions and services, as well as avoidance of treatment for fear of the virus. In fact, the WHO reported a global deterioration of mental health services during the pandemic, simultaneously with a deterioration in the mental health status of the population43. The potential long-term consequences of the pandemic on mental health, particularly of young people, are worrisome: in a July/August 2021 OECD survey, 151 youth organizations assessed the areas where young people found it most difficult to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 crisis, and mental health was the top concern44. The direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic have exacerbated the risk factors for poor mental health and weakened many of the protective factors, leading to a significant deterioration in the mental health of the population. In this context, our study shows that while confirmed to be increasing, the rate of increase is lower than during the pre-pandemic period. This is in contrast to what is observed in, for example, France, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, where consumption of relevantly exceeded the expected trends during the COVID- 19 pandemic21,24. Similar results to ours, on the other hand, are observed in Croatia, where the increase in antidepressant consumption is maintained even during and after the pandemic, although the annual rates of increase turn out to be similar or lower than the pre-pandemic period22. Similarly, in Portugal an increasing trend was observed until the onset of the pandemic but since then, a decrease trend was observed23.

Our study has the following limitations. For the drug classes SNRIs and TCAs, several years of data are missing. Similarly, data on demographic characteristics (such as age, gender, regional disparities) are not continuosly reported and due to this etherogenity in data it is not possible to include a stratified analysis for these variables. However, the data are obtained from official sources and the available data allow for a sufficently trend to be analyzed. As already mentioned, antidepressants may have been prescribed and/or used for different therapeutic indications and, therefore, for conditions that are not strictly psychiatric. A further limitation is that the data available reflected the drugs prescribed and not drugs that are really consumed by the population. In fact, it is not possible to quantify the discrepancy between the two data as it could be caused, for example, by poor compliance or early discontinuation of therapy. Moreover, the indicator included only drugs prescribed by professionals of the NHS and, therefore, subject to reimbursement, while it was not possible to quantify changes in consumption related to out-of-pocket prescriptions.

Conclusion

The consumption of antidepressants in Italy is increasing, and this figure should be carefully considered and monitored. Prescribing such drugs, in fact, should be based on a careful assessment of the patient and the level of depression, the data on efficacy and the response rates associated with these treatments45,46,47.

In this context, it is necessary to address in the appropriate government forums this public health issue. It turns out to be essential, in this perspective, to increase spending dedicated to mental health, which in the world accounts for only 2% of all health spending, a percentage that is insufficient to cover the needs of patients, considering also that treatments involving pathologies in this area are often excluded from benefits covered by health insurance48. It appears crucial to monitor mental health indicators of the general population, which is essential to improving the quality of services currently guaranteed, implementing complementary solutions to pharmacotherapy, as well as to plan strategies to prevent the disease and to promote population resilience, so it will be imperative to monitor the impact and consequences of the pandemic on mental health in the coming years49.

Challenges related to accessibility of mental health care are not new, with a large percentage of people seeking mental health care having difficulty obtaining it before the pandemic50. In response, European countries have taken steps to increase support for mental health, such as developing new mental health information channels, increasing entitlement to mental health services, and providing more funding to support the availability and use of these services, albeit it still appears insufficient48,51.

Training is appropriate in order to easily identify the growing proportion of patients who need mental health care. In particular, the implementation of psychiatric support in the healthcare system, particularly in primary care settings, could be helpful52,53.

Methods

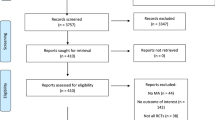

Data collection

We considered data concerning the total consumption of antidepressants in the Italian population and three subclasses of the most widely used antidepressant drugs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).

Data on the consumption of antidepressants were obtained from Osservasalute, an annual report published by the National Observatory on Health Status in the Italian Regions, that collects and processes data from major Italian institutions regarding more than 200 health indicators validated at international level54. Data on SSRIs, SNRIs and TCAs consumption were collected from the Italian Medicine Agency (AIFA) through the OsMed reports40.

Data were expressed as the daily defined dose (DDD) per 1,000 inhabitants. The DDD is defined as the assumed average maintenance daily dose of a drug. It is a unit of measurement of drug use adopted in studies and surveys at national and international level, approved and recommended by the WHO55. The DDD per 1,000 inhabitants measures how many individuals received a standard dose of a specific drug daily. In addition, the resident population considered in the indicators produced by Osservasalute and OsMed reports are developed as weighted according to the weighting system organized on seven age groups, as established by the Department of Planning of the Ministry of Health for the allocation of the capitated share of the National Health Fund.

In our analysis we considered the last 15 years, from 2008 (or more recently if not available) to 2022 (or latest data available). In particular, data on SNRIs were available from 2013 to 2022, while data on TCAs were available from 2008 to 2019.

Data analysis

We performed a Joinpoint regression analysis to describe changes in antidepressants consumption. Joinpoint is a model used to analyze temporal trend changes across many scientific fields56,57,58,59. The model identifies a point (“joinpoint”) where parameter shifts occur within a time series. We considered the year as the independent variable, while the consumption of antidepressants, expressed as a proportion, as the dependent variable. We assumed constant variance, defined as homoscedasticity. To identify the increase or decrease of the trend, the joinpoint model calculates the Annual Percentage Change (APC) over time for each interval considered. The model also calculated the Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC), a measure of the trend over the whole interval considered, computed as a weighted average of the APCs from the joinpoint model. The software predicts a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 5 joinpoints, showing the presence of changes in the trend that is considered significant when p < 0.05.

We used the Joinpoint Trend Analysis Software 5.0.2 – Desktop Version, available from the Surveillance Research Program of the US National Cancer Institute60.

Data availability

The data on antidepressants are obtained from Osservasalute, annual report published by the National Observatory on Health Status in the Italian Regions. Access to data is public and free at the following link: https://osservatoriosullasalute.it/.Data on SSRIs, SNRIs and TCAs are are obtained from OsMed reports, published by the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Nazionale del Farmaco – AIFA) at the following link: https://www.aifa.gov.it/uso-dei-farmaci-in-italia).

References

Sheehan, D. V., Nakagome, K., Asami, Y., Pappadopulos, E. A. & Boucher, M. Restoring function in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 215, 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.029 (2017).

Beck, A. et al. Severity of depression and magnitude of productivity loss. Ann. Fam Med. 9, 305–311 (2011).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Compare. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (2021).

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and National burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 9, 137–150 (2022).

Liu, J., Liu, Y., Ma, W., Tong, Y. & Zheng, J. Temporal and Spatial trend analysis of all-cause depression burden based on global burden of disease (GBD) 2019 study. Sci. Rep. 14, 458 (2024).

World Health Organization (WHO). Depressive disorder (depression). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (2024).

World Health Organization (WHO). Global Burden of Mental Disorders and the Need for a Comprehensive, Coordinated Response from Health and Social Sectors at the Country Level (2011).

Santomauro, D. F. et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398, 1700–1712 (2021).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Tackling the Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis: an Integrated, Whole-of-Society Response (2021).

Gualano, M. R., Lo Moro, G., Voglino, G., Bert, F. & Siliquini, R. Monitoring the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: a public health challenge? Reflection on Italian data. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 56, 165–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01971-0 (2021).

National Health Service - United Kingdom National Health Service. Overview—Antidepressants. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/talking-therapies-medicine-treatments/medicines-and-psychiatry/antidepressants/overview/ (2024).

Alemi, F. et al. Effectiveness of common antidepressants: a post market release study. EClinicalMedicine 41, 14 (2021).

Damiani, G. et al. Impact of regional copayment policy on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) consumption and expenditure in Italy. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 69, 957–963 (2013).

Olfson, M. & Marcus, S. C. National Patterns in Antidepressant Medication Treatment (2024).

Exeter, D., Robinson, E. & Wheeler, A. Antidepressant dispensing trends in new Zealand between 2004 and 2007. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 43, 896 (2009).

Martín Arias, L. H. et al. Trends in the consumption of antidepressants in Castilla y León (Spain). Association between suicide rates and antidepressant drug consumption. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 19, 895–900 (2010).

Verdoux, H., Tournier, M. & Bégaud, B. Antipsychotic prescribing trends: a review of pharmaco-epidemiological studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 121, 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01425.x (2010).

Gualano, M. R. et al. Consumption of antidepressants in Italy: recent trends and their significance for public health. Psychiatric Serv. 65, 1226–1231 (2014).

OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/7a7afb35-en (2023).

Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Depressione in Italia anni 2021–2022. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/passi/dati/depressione#:~:text=Dai%20dati%20PASSI%202021%2D2022,le%20persone%20senza%20sintomi%20depressivi (2023).

Tiger, M. et al. Utilization of antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics during the COVID-19 pandemic in Scandinavia. J. Affect. Disord. 323, 292–298 (2023).

Vukićević, T., Draganić, P., Škribulja, M., Puljak, L. & Došenović, S. Consumption of psychotropic drugs in Croatia before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a 10-year longitudinal study (2012–2021). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 59, 799–811 (2024).

Estrela, M. et al. Prescription of anxiolytics, sedatives, hypnotics and antidepressants in outpatient, universal care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal: a nationwide, interrupted time-series approach. J. Epidemiol. Community Health (1978). 76, 335–340 (2022).

De Bandt, D., Haile, S. R., Devillers, L., Bourrion, B. & Menges, D. Prescriptions of antidepressants and anxiolytics in France 2012–2022 and changes with the COVID-19 pandemic: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ Mental Health 27, 71 (2024).

Bogowicz, P. et al. Trends and variation in antidepressant prescribing in english primary care: a retrospective longitudinal study. BJGP Open. 5, 1–12 (2021).

Gusmão, R. et al. Antidepressant utilization and suicide in Europe: an ecological Multi-National study. PLoS One 8,b145 (2013).

Peano, A. et al. International trends in antidepressant consumption: a 10-year comparative analysis (2010–2020). Psychiatr. Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-025-10122-0 (2025).

Mcintyre, R. S. et al. Treatment-resistant depression: definition, prevalence, detection, management, and investigational interventions. World Psychiatry 2023, 394–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21120 (2023).

Saragoussi, D. et al. Factors associated with failure to achieve remission and with relapse after remission in patients with major depressive disorder in the PERFORM study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 13, 2151–2165 (2017).

Karasu, B., Üniversitesi, Y., Wang, P., Altshuler, K. Z. & Tasman, A. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (Revision). http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx (2000).

Pratt, L. A., Brody, D. J. & Gu, Q. Antidepressant Use in Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2005–2008 Key Findings Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. NCHS Data Brief (2005).

Pratt, L. A., Brody, D. J. & Gu, Q. Antidepressant Use Among Persons Aged 12 and Over: United States, 2011–2014 Key Findings Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db283_table.pdf#2 (2011).

Brisnik, V. et al. Deprescribing of antidepressants: development of indicators of high-risk and overprescribing using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. BMC Med. 22, (2024).

Trifirò, G. et al. A nationwide prospective study on prescribing pattern of antidepressant drugs in Italian primary care. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 69, 227–236 (2013).

Connolly, K. R. & Thase, M. E. Emerging drugs for major depressive disorder. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 17, 105–126. https://doi.org/10.1517/14728214.2012.660146 (2012).

Ilyas, S. & Moncrieff, J. Trends in prescriptions and costs of drugs for mental disorders in England, 1998–2010. Br. J. Psychiatry 200, 393–398 (2012).

Arnaud, A., Suthoff, E., Tavares, R. M., Zhang, X. & Ravindranath, A. J. The increasing economic burden with additional steps of pharmacotherapy in major depressive disorder. Pharmacoeconomics 39, 691–706 (2021).

Jannini, T. B. et al. Off-label uses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Curr. Neuropharmacol. 20, 693–712 (2021).

Ministero della Salute. Piano Di Azioni Nazionale Per La Salute Mentale (2013).

Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA). Rapporti OsMed. https://www.aifa.gov.it/rapporti-osmed (2024).

Bishop, M. M., Fixen, D. R., Linnebur, S. A. & Pearson, S. M. Cognitive effects of vortioxetine in older adults: a systematic review. Therapeut. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 11. https://doi.org/10.1177/20451253211026796 (2021).

Kok, R. M. & Reynolds, C. F. Management of depression in older adults: a review. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 317, 2114–2122. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.5706 (2017).

World Health Organization (WHO). The Impact of COVID-19 on Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Services: Results of a Rapid Assessment (2020).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Delivering for youth: how governments can put young people at the centre of the recovery. https://doi.org/10.1787/92c9d060-en (2022).

Köhler-Forsberg, O. et al. Efficacy and safety of antidepressants in patients with comorbid depression and medical diseases: an umbrella systematic review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 80, 1196–1207 (2023).

Cipriani, A. et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 391, 1357–1366 (2018).

Gibbons, R. D., Hur, K., Brown, C. H., Davis, J. M. & Mann, J. J. Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of Fluoxetine and Venlafaxine. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 69, 572–579 (2012).

Thornicroft, G. et al. The Lancet Commission on ending stigma and discrimination in mental health. The Lancet 400, 1438–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01470-2 (2022).

Rabeea, S. A. et al. Surging trends in prescriptions and costs of antidepressants in England amid COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40199-021-00390-z/Published (2021).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). A new benchmark for mental health systems. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/4ed890f6-en (2021).

Sándor, E. et al. Impact of COVID-19 on young people in the EU. Www Eurofound Europa Eu. https://doi.org/10.2806/06591 (2021).

Johnson, C. F., Williams, B., Macgillivray, S. A., Dougall, N. J. & Maxwell, M. ‘Doing the right thing’: factors influencing GP prescribing of antidepressants and prescribed doses. BMC Fam. Pract. 18, 1456 (2017).

Verdoux, H., Cortaredona, S., Dumesnil, H., Sebbah, R. & Verger, P. Psychotherapy for depression in primary care: a panel survey of general practitioners’ opinion and prescribing practice. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 49, 59–68 (2014).

Osservatorio Nazionale sulla Salute nelle Regioni Italiane. Rapporto Osservasalute. https://osservatoriosullasalute.it/rapporto-osservasalute (2024).

World Health Organization (WHO). Defined Daily Dose (DDD). https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/about-ddd (2024).

Kim, H. J. et al. Data-driven choice of a model selection method in joinpoint regression. J. Appl. Stat. 50, 1992–2013 (2023).

Aguinaga-Ontoso, I. et al. COVID-19 impact on DTP vaccination trends in Africa: a joinpoint regression analysis. Vaccines (Basel) 11, 1103 (2023).

Gillis, D. & Edwards, B. P. M. The utility of joinpoint regression for estimating population parameters given changes in population structure. Heliyon 5, e02515 (2019).

Long, N. P. et al. Scientific productivity on research in ethical issues over the past half century: a joinpoint regression analysis. Trop. Med. Health 42, 121–126 (2014).

National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint trend analysis software. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/ (2024).

Acknowledgments

Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore contributed to the funding of this research project and its publication.

Funding

The authors declare they have not received funding to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. MRG conceived the research hypothesis. Material preparation and data collection were performed by MOI and LV. LV performed statistical analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MOI, SM and LV. WR and MRG commented on the latest version of the manuscript. MRG supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oscoz-Irurozqui, M., Villani, L., Martinelli, S. et al. Trend analysis of antidepressant consumption in Italy from 2008 to 2022 in a public health perspective. Sci Rep 15, 12124 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96037-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96037-z