Abstract

This study investigates whether the combined effect of kinesthetic motor imagery-based brain computer interface (KI-BCI) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on upper limb function in subacute stroke patients is more effective than using KI-BCI or tDCS alone. Forty-eight subacute stroke survivors were randomized to the KI-BCI, tDCS, or BCI-tDCS group. The KI-BCI group performed 30 min of KI-BCI training. Patients in tDCS group received 30 min of tDCS. Patients in BCI-tDCS group received 15 min of tDCS and 15 min of KI-BCI. The treatment cycle was five times a week, for four weeks. After all intervention, the Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Upper Extremity, Motor Status Scale, and the Modified Barthel Index scores of the KI-BCI group were superior to those of the tDCS group. The BCI-tDCS group was superior to the tDCS group in terms of the Motor Status Scale. Although quantitative EEG showed no significant group differences, the quantitative EEG indices in the tDCS group were significantly lower than before treatment. In conclusion, after treatment, although all intervention strategies improved upper limb motor function and daily living abilities in subacute stroke patients, KI-BCI demonstrated significantly better efficacy than tDCS. Under the same total treatment duration, the combined use of tDCS and KI-BCI did not achieve the hypothesized optimal outcome. Notably, tDCS reduced QEEG indices, possibly indicating favorable future outcomes in future.

Trial registry number: ChiCTR2000034730.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is the second-leading cause of death and the third-leading cause of disability worldwide1. Epidemiological studies indicate that approximately 80% of stroke survivors experience persistent upper extremity motor impairment during the acute phase2, resulting in substantial limitations in both physical functioning and social participation3. The recovery process is fundamentally mediated by intrinsic neuroplastic mechanisms, including both physiological and anatomical adaptations, which facilitate functional motor improvement4,5. Notably, these neuroplastic changes evolve through distinct temporal phases, with gradual synaptic reorganization emerging during the subacute period spanning days to weeks post-stroke.

Based on the principles of Hebbian plasticity, post-stroke motor recovery requires not only cortical motor control activation but also functional transmission of motor commands to muscle effectors, thereby engaging complete cortico-muscular pathways6. Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) establish direct communication channels between users and computers, circumventing conventional neural pathways between the brain and muscles7. When utilized for motor neuromodulation, BCI systems facilitate activity-dependent plasticity by enabling users to concentrate on tasks that modulate specific neural signals8,9. Electroencephalography (EEG) has become the predominant modality for BCI systems due to its noninvasive nature, excellent temporal resolution, potential for user mobility, and cost-effectiveness10. EEG-based BCIs are broadly categorized into evoked and spontaneous systems11. Evoked systems rely on external stimuli (visual, auditory, or sensory) to elicit brain responses that the BCI system interprets to determine user intent12. In contrast, spontaneous BCIs operate without external stimuli, utilizing brain activity generated through mental processes11.Motor imagery (MI)-based BCIs represent a prominent example of spontaneous systems13. MI, the cognitive simulation of movement without physical execution, was developed based on neuroplasticity principles14. This approach offers particular advantages for stroke rehabilitation, enabling patients with severe motor impairments to engage in therapeutic interventions15. MI paradigms primarily encompass visual imagery (VI) and kinesthetic imagery (KI). VI involves the visualization of limb movement from either a first-person or third-person perspective16,17,18, while KI entails the mental simulation of the somatosensory experience associated with performing the movement19. Both modalities facilitate information processing and cortical activation, though distinct neural mechanisms20. While both VI and KI have demonstrated efficacy in BCI applications, empirical evidence suggests KI’s superior performance. Marchesotti et al.21 established a correlation between BCI proficiency and paradigm adaptability, demonstrating that users with higher BCI aptitude achieve better MI-EEG decoding accuracy with KI paradigms. These findings were corroborated by Toriyama et al.22, whose comparative studies revealed stronger event-related desynchronization patterns during KI, showing greater similarity to actual motor execution.

Noninvasive brain stimulation techniques have emerged as valuable tools for monitoring and modulating the excitability of intracortical neuronal circuits, with the capacity to induce lasting neurophysiological changes through prolonged cortical stimulation. Among these techniques, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) has gained considerable attention for its neuromodulatory potential. tDCS delivers constant low-intensity direct current (1–2 mA) to targeted cortical regions, thereby modulating neuronal activity in the cerebral cortex23. The underlying mechanism involves the regulation of resting membrane potentials through modulation of sodium- and calcium-dependent channels, along with N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activity24. Post-stroke neurophysiology is characterized by an imbalance in interhemispheric cortical activity, with the affected hemisphere exhibiting increased excitability and diminished local inhibitory circuit activity25. TDCS offers a targeted approach to address this imbalance: anodal stimulation induces neuronal depolarization to enhance cortical excitability, while cathodal stimulation promotes hyperpolarization to reduce excitability26. This polarity-specific modulation enables precise regulation of cortical excitability, potentially facilitating plastic reorganization within the sensorimotor network. Consequently, tDCS represents a promising therapeutic approach for improving upper limb function in subacute stroke patients through targeted neuromodulation.

This study aims to investigate the synergistic potential of combining anodal tDCS with BCI interventions for motor rehabilitation in subacute stroke patients. Previous research27 involving healthy participants demonstrated that the combination of anodal tDCS and BCI interventions induce significant neurophysiological changes. These changes include altered directed connectivity between frontal and parietal regions, and enhanced information flow between the premotor cortex and sensorimotor cortex during MI tasks. Importantly, these neurophysiological modifications were behaviorally relevant, correlating with improved task performance as evidenced by increased correct trials and reduced completion times. Building on these findings, recent studies have suggested that both KI-BCI and tDCS independently facilitate motor rehabilitation in stroke patients through cortical plasticity modulation28,29. The subacute phase of stroke recovery (14–180 days) represents a critical therapeutic window, characterized by approximately 90 days of enhanced synaptic plasticity that parallels the period of most rapid behavioral recovery25. Within this context, we hypothesized that: (1) both KI-BCI and tDCS would significantly improve upper limb function in subacute stroke patients, and (2) the combined intervention would demonstrate superior efficacy compared to either treatment alone. Furthermore, we aimed to elucidate the underlying neural mechanisms through quantitative EEG analysis.

To test these hypotheses, we conducted a three-armed randomized controlled trial comparing KI-BCI, tDCS, and their combination. The study specifically focused on the subacute phase to capitalize on the period of heightened neuroplasticity, while addressing the current uncertainty regarding the efficacy of combined tDCS-BCI interventions in clinical populations.

Methods

Trial design

This study was a randomized controlled study. Participants who are participants with subacute stroke received either 20 sessions of KI-BCI, tDCS or KI-BCI combined with tDCS. This study was conducted under the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of Xuzhou Rehabilitation Hospital approved the entire protocol and instrumentation (No. XK-LW-20200428-003) and was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry Platform (identifier: ChiCTR2000034730, registered on 16/07/2020). All participants signed an informed consent form before the start of the trial.

Participants

Participants were recruited from Xuzhou Rehabilitation Hospital between July 2020 to December 2023.Those participants were then evaluated for eligibility after being introduced to the study. Inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: (1) first-ever stroke diagnosed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (chronicity ≥ 14 and < 180 days); (2) Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)30 score ≥ 20; and (3) aged between 40 and 80 years. Participants with subacute stroke were excluded if they: (1) history of seizures; (2) other neurological, neuromuscular, orthopedic diseases; (3) a scalp deformity due to surgery; or (4) with medical instability such as heart/respiratory failure, deep venous thrombosis, acute myocardial infarction, non-compensated diabetes, active liver disease, or/and kidney dysfunction medication of antispastic therapy (any antispastic medicine or botulinum toxin injection). If the following conditions occurred during the treatment process, the participant’s experimental process was terminated: (1) progressive aggravation of the condition; (2) poor compliance; or (3) occurrence of epilepsy, manic episodes or other conditions after treatment.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated using PASS version 15.0 (NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, Utah, The United States). The calculation was based on the Fugl-Meyer Assessment for Upper Extremity (FMA-UE)31. The presumed effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.353) was derived from our pilot study involving 5 participants per group (total sample size = 15), where the observed group differences yielded an F-value of 0.751, which was used to estimate the effect size. With a type I error of 0.05 and a power of 0.90, the estimated sample size was 14 participants per group. To account for a potential dropout rate of 20%, we included 16 participants per group in the main study.

Randomization and blinding

We used a computerized randomization scheme to randomize 48 participants with subacute stroke into three groups: KI-BCI group (n = 16), tDCS group (n = 16), an BCI-tDCS group (n = 16). Before recruitment, an unrelated assistant developed a computer-generated random sequence and stored it in sealed, sequentially envelopes labeled with the name of one of the three groups. Due to the way of intervention, physical therapists were not blinded. Evaluators were independent of the intervention and were blinded to the assigned group.

Interventions

The participants were invited for an initial assessment to verify their eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. Upon providing informed consent, eligible participants were assigned to one of three groups. The treatment protocol is displayed in Table 1.

Conventional intervention

All participants received conventional interventions, including mobilization, neural facilitation techniques, sit-to-stand exercises, balance training, and functional electrical stimulation to mitigate the effects of non-use and muscle atrophy. Participants in Brunnstrom stages I-III also underwent virtual reality training with an intelligent feedback system (A2, Guangzhou Yikang). This system created suitable 3D game environments displayed on a large screen. The machine arm’s weight and range of motion were adjusted according to the participants’ affected arms. Training involved voice prompts to guide participants in specific movements, enhancing shoulder flexion/extension, adduction/abduction, hand grasping, and joint coordination.

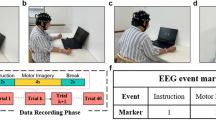

Participants at Brunnstrom stage IV and above trained with the BioMaster virtual scenario training system (Guangzhou Zhanghe Electrical). A wireless motion sensor evaluated their upper limb movement before training. The system generated personalized VR simulations, including activities such as ball striking, target shooting, virtual egg frying, and apple picking, all aimed at enhancing elbow, wrist, and forearm joint mobility. Figure 1 illustrates the state of the patients during virtual reality training. Conventional therapy was conducted once daily for 30 min.

KI-BCI

To avoid interference with the EEG signals, the training took place in a dimly lit and quiet environment. Participants were guided by an experienced therapist to relax their body and focus on MI tasks. The L-B300 EEG Acquisition and Rehabilitation Training System (Zhejiang Mailian Medical Technology Co., Ltd.) provided visual and auditory cues to facilitate the tasks. Specifically, participants were instructed to imagine themselves performing freestyle swimming in a virtual pool, vividly visualizing their upper limbs alternately pushing through the water to move forward. This imagined movement was consistent across all sessions, with no fixed number of repetitions per session but a fixed total duration. The number of completed movements depended on the participant’s MI performance, as the system only advanced the virtual scene and activated the robotic arm when the participant’s imagery score exceeded a predefined threshold.

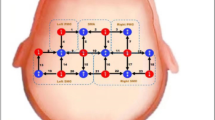

The BCI system collected EEG signals from the prefrontal motor regions (FP1, FP2, F3, F4, C3, C4, Fz, Cz) (see in Fig. 2) and calculated MI scores by comparing real-time EEG data to an individualized Movement-Related Cortical Potential (MRCP) model. The MRCP occurs naturally right before the movement attempt, reaching the maximum negativity near the movement onset32,33. It was shown to be able to decode movement intention34 and to discriminate between different upper-limb movements35. This model was constructed during the paradigm training phase, capturing each participant’s unique neural patterns during MI. The MI score was derived from a composite similarity metric that integrates Pearson correlation coefficients and Dynamic Time Warping (DTW). DTW, which identifies the minimum path by providing non-linear alignments between two time series, has been widely used as a distance measure for time-series classification and clustering36. This approach allows for the assessment of both linear and non-linear similarities between EEG signals and the MRCP model. If the score met or exceeded the threshold, the system entered an active-assisted movement mode, where a robotic arm (an upper extremity ergometer) assisted the participant’s affected upper limb to complete the task. Unlike conventional robotic training, the ergometer in our system is only activated by sufficiently strong and clear MI signals. This establishes a closed-loop interaction between the central and peripheral systems, rather than the open-loop peripheral stimulation seen in conventional robotic training. If the threshold was not reached, no feedback was provided, ensuring that assistance was only given during successful MI. Each training session conducted once daily, five times per week, over four weeks.

tDCS

ActivaDose®II portable transcranial direct current stimulator (Wogao Medical Equipment Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) was used to intervene in the central nervous system of participants with subacute stroke. The motor evoked potential module of the Magstim Rapid2 repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulator (Magstim, UK) was used to locate M1, and the best stimulation point of M1 was found by adjusting the intensity and direction of the stimulation coil.

In this study, the unilateral stimulation mode of tDCS was used. The anode was positioned over the M1 on the affected hemisphere, while the cathode was placed over the contralateral orbit. The electrode piece was a 5 cm × 5 cm isotonic saline sponge electrode. The total current intensity was 2 mA, and the treatment lasted 20 min, performed for 1 session per day, with each session lasting 20 min, totaling 5 sessions per week for 4 weeks.

Outcome measures

Demographic and anthropometric data of the participants were collected at baseline. Measurements were carried out before and four weeks after the intervention began to observe the effects of the three interventions and the trends of changes over different time periods.

Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Upper extremity (FMA-UE)

The FMA-UE is the most commonly used assessment for measuring post-stroke impairment37,38. It evaluates the motor function of the upper limbs, wrists, and hands. It includes 4 subsections: (1) shoulder-arm, (2) wrist, (3) hand, and (4) coordination and speed designed to measure impairment from proximal to distal and synergistic to isolated voluntary movement39. The 33 items are scored on an ordinal scale of 0 (absent), 1 (partial impairment), and 2 (no impairment) that make up a total maximum of 66 points40.

Motor status scale (MSS)

The MSS measures shoulder, elbow, wrist, and finger movements, which developed based on the FMA and expanded the measurements on fingers and has gone through reliability and validity studies in subacute survivors41,42.

The modified Barthel index (MBI)

The MBI is used to evaluate participants’ activities of daily living (ADL) levels, and consists of 10 items: bowel control, bladder control, grooming, bathing, eating, dressing, toileting, climbing stairs, transferring, and walking. Each item is scored from 0 to 15 based on the participant’s ability to complete the task. A higher score indicates a better ability to function independently43.

The action research arm test (ARAT)

The ARAT is a standardized assessment tool for evaluating upper limb fine motor function, comprising 19 items across four distinct domains: grasp, grip, pinch, and gross movement. Each item is scored on an ordinal scale, yielding a total possible score of 57 points44. The ARAT demonstrates strong psychometric properties, with higher total scores indicating better upper limb functional capacity31.

Electroencephalography acquisition, processing, and analysis

32-channel (NeuSen.W32, Neuracle, China) EEG signals were collected at a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz. The 32-channel Al-AgCl electrodes were distributed according to the 10–20 system standards as shown in Fig. 3. Before the EEG recordings, preparation procedures including hair cleaning, cap positioning, and impedance checking were conducted to ensure that the electrode-to-scalp impedance was below 5 kΩ. Participants were sat comfortably in a quiet, dim, electrically shielded room. An experienced EEG technician instructed participants to keep their upper extremity still and minimize blink frequency. The recording began after the EEG signals had stabilized.

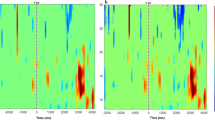

If there were large artifacts in the range of 0–30 Hz, these EEG signals were discarded. Then, the 5th-order IIR filter in EEGLAB (2023 version) was used to apply low pass filtering with 30 Hz to the remaining EEG signals, where the baseline drift was removed and overflowed. Independent component analysis (ICA) was used to remove artifacts: EEGLAB’s default runica algorithm was used to calculate ICA, and we used EEGLAB’s ‘adjust’ plugin to remove 3 of the 32 independent components, thus removing the ECG and EOG artifacts45,46. Fourier transform was used for time-frequency conversion, dividing the frequency range into alpha (8–13 Hz), beta (14–30 Hz), theta (4–7 Hz), and delta (0.5–3 Hz) waves. We selected electrical signals from the frontal motor areas (FP1, FP2, F3, F4, C3, C4, Fz, and Cz) and analyzed them. Quantitative EEG indicators enclose a vast array of information on neural activity, such as oscillation, neural interplay, network and spatial distribution47. In this study, three quantitative EEG indicators DAR, DTABR, and DABR were calculated.

\({\hat {p}_x}\left( x \right)\) is the power spectrum density (PSD), Pα, Pβ, Pθ, and Pδ are the PSD of α, β, θ, and δ bands, respectively. DAR and DTABR have the potential to prognosticate post-stroke motor and functional disability48. A greater DAR was related to poorer outcome49. In stroke patients, DTABR showed a significant correlation with the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at month 6 (Spearman ρ = 0.47) and was identified as an independent predictor of dependency (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.16–4.37, p = 0.016), alongside NIHSS (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.09–1.37, p < 0.0005)50. Poor outcomes were predicted by delta activity and depression of alpha or beta activity in the ischaemic hemisphere, whereas good outcomes were predicted by absence of these phenomena51.By quantifying the relative dominance of delta power over alpha and beta bands, the DABR provides a comprehensive index of neural disruption and recovery potential in stroke patients. Through these three indicators, we can understand the changes in neuroplasticity of the subjects and predict their future functional outcomes.

Statistical analysis

All data were collected at two time points: before the intervention (pre-intervention) and immediately after the 4-week intervention (post-intervention). There were no intermediate test sessions during the intervention period. The measurement data were expressed as mean (SD). The Shapiro-wilk test was performed to test for a normal distribution, and Levene’s test was applied to check the equality of variance for all measures. Differences in demographic and clinical variables, including FMA-UE, MSS, ARAT, MBI, and EEG indicators such as DAR, DTABR, and DABR, between groups at baseline were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis analysis, depending on whether the data distribution was normal or not. A post-hoc check of the baseline data was performed using Tukey’s method to avoid family-wise errors.

A mixed-model ANOVA was used to see the time effect, group effect, and time × group interaction effect between the three groups. Mauchly’s test was used to justify the sphericity of the variance-covariance matrix. If the variance-covariance matrix lacked sphericity, Greenhouse-Geisser was used to correct it. Baseline values were added as covariates in the analysis to eliminate the effect of confounding factors on the results. The partial eta squared ηp2 was obtained from Greenhouse-Geisser within the subject effect. A significance level of 0.05 was established, and all statistical analyses were completed with SPSS software, version 26 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, the United States).

Results

Participants characteristics

The flowchart for participants is presented in Fig. 4. We screened 81 participants for eligibility, and 33 were excluded. Therefore, 48 participants were enrolled, assessed at baseline, and randomly assigned into 3 groups. The participants’ baseline demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. No significant differences were observed between the groups regarding age, gender, stroke type, affected side, and time from onset (Table 2). In addition, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of clinical outcomes and brain function at baseline.

Clinical outcomes

FMA-UE

There were significant time effects (F = 391.500, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.960) and interaction effects (F = 11.596, P = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.659) for FMA-UE. Between group comparisons showed that the FMA-UE of the KI-BCI group was significantly greater than the tDCS group (P = 0.003) (Table 3).

MSS

There were significant time effects (F = 560.419, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.977), group effects (F = 6.609, P = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.337) and interaction effects (F = 8.445, P = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.394). Between group comparisons showed that the MSS score (P = 0.003) of the KI-BCI group (P = 0.003) and the BCI-tDCS group (P = 0.011) were superior to the tDCS group (Table 3).

ARAT

There were significant time effects (F = 93.450, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.878) and interaction effects (F = 10.995, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.458) for the ARAT. After 4 weeks intervention, there was no statistical difference among the three groups (Table 3).

MBI

There were significant time effects (F = 761.997, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.983) and interaction effects (F =11.024, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.803) for the MBI. After 4 weeks intervention, the MBI of KI-BCI group was superior to the tDCS group (P = 0.005) (Table 3).

Quantitative EEG indicators

After 4 weeks of intervention, there was no statistical difference in time, group, and interaction (time × group) effect for the DTABR, DAR, and DABR among the three groups. However, the DABR (P = 0.024), DAR (P = 0.022), and DTABR (P = 0.023) of the tDCS group were significantly higher than those before the intervention. There was no significant difference in DABR between the KI-BCI group and the BCI-tDCS group after the intervention (Table 4).

Discussion

This randomized controlled study investigated whether the combined effect of KI-BCI and tDCS on upper limb function in participants with subacute stroke is more effective than the effect of KI-BCI or tDCS alone. Our results showed that KI-BCI training combined with tDCS significantly improved upper extremity function (include fingers, see in MSS score) compared with tDCS alone. There was no statistically difference between the KI-BCI combined with tDCS or use KI-BCI alone. In contrast, participants with subacute stroke who received KI-BCI training alone showed better performance in allover upper limb function and ADL than those who received tDCS alone. In terms of neurophysiological indicators, there were no significant differences among the three groups after intervention, but the participants in tDCS group showed lower quantitative EEG indicators compared to before treatment.

Based on previous research, we hypothesized that the combination of tDCS-induced synaptic plasticity and motor cortex activation through KI-BCI would synergistically enhance neuroplasticity beyond the effects of either intervention alone. However, our findings did not support this hypothesis. Notably, the KI-BCI group demonstrated superior performance across all three upper limb function assessments (FMA-UE, MSS, and ARAT). We propose several potential mechanisms to explain these results. First, the KI-BCI intervention likely achieved greater efficacy by completing the central-peripheral closed-loop process, a feature absent in open-loop tDCS. Unlike tDCS, which operates independently of natural brain activity, KI-BCI relies on intrinsic brain activity patterns, engaging neurons directly involved in motor association processes. This engagement may lead to more targeted and functionally relevant plastic changes, as the same neural circuits are activated during both training and voluntary motor efforts52.Second, the KI-BCI protocol specifically enhanced motor performance through its integration with robotic assistance. During training, the MI-activated robotic system facilitated shoulder pronation-supination, elbow flexion-extension, and wrist flexion-extension movements, providing direct support for motor execution. This approach aligns with evidence suggesting that interventions targeting distal motor function—such as robot-assisted therapy, EMG stimulation, and bilateral movement training—are effective across various post-stroke stages, even in the absence of validated neurophysiological criteria53. This could be one of the reasons why the MSS scores in the BCI-tDCS group were higher than those in the tDCS group. Finally, the coupling of KI with robot-assisted arm movement through BCI may have enhanced sensorimotor integration. By bridging motor intent with somatosensory feedback through passive manipulation of the paretic arm, this approach likely promoted activity-dependent cortical plasticity. The continuous feedback on brain activity during task execution further reinforced these plastic changes, creating a more robust rehabilitation effect54.

In addition to the differences in cortical-peripheral input between closed-loop and open-loop interventions mentioned above, the variation in upper limb outcomes between the BCI-tDCS group and the tDCS group post-intervention may also be attributed to the fact that tDCS alone is not particularly effective in improving upper limb function in stroke patients. Recent randomized studies and meta-analyses of active vs. sham tDCS have found no clear evidence of improvement to upper paretic limb function following any of the tDCS protocols55,56,57.

The transition from neurofeedback to actual motor performance relies critically on transfer learning, a process whose efficacy is modulated by multiple factors, including learning protocols, cognitive strategies, and contextual conditions58. Notably, the BCI-tDCS group failed to demonstrate significant improvements in upper limb function compared to the KI-BCI group, a finding that may be closely related to limitations in training methodology and duration. Specifically, the BCI-tDCS protocol allocated only 15 min per session to KI-BCI training, with an even shorter duration dedicated to active limb movement. This restricted training time likely resulted in insufficient motor transfer duration, thereby compromising the overall efficacy of transfer learning. Furthermore, the observed performance discrepancy may be attributed to additional factors, such as inter-individual variability in participants’ cognitive aptitude for task execution, differences in attentional focus during feedback processing, and the degree of flexibility in adapting mental strategies based on real-time feedback58. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing training parameters and individualizing intervention strategies to maximize transfer learning efficacy in neurorehabilitation settings.

The analysis revealed distinct patterns in motor function outcomes across the three intervention groups. Both the KI-BCI and BCI-tDCS groups achieved significantly higher MSS scores compared to the tDCS group. However, in the FMA-UE, only the KI-BCI group demonstrated significantly superior performance relative to the tDCS group. This discrepancy can be attributed to the distinct focus of the two assessment tools. Although the MSS is derived from the FMA, they evaluate different dimensions of motor function. The FMA-UE provides a comprehensive assessment of overall motor function, including reflexes, movement patterns, fine finger movements, and coordination. In contrast, the MSS specifically targets isolated movements of the upper limb, such as shoulder, elbow, wrist, and hand functions. Despite a strong correlation between the two scales, their differing emphases likely account for the observed score variations. From the specific data of the patients, we observed that higher FMA-UE scores were consistently associated with elevated MSS scores across the patient cohort, underscoring the complementary nature of these assessments in evaluating motor recovery. These findings highlight the importance of utilizing multiple assessment tools to capture the full spectrum of motor function improvements in stroke rehabilitation.

This study also aims to explore the underlying neural mechanisms of these interventions through quantitative EEG indicators. In this study, only the tDCS group showed a significant change in the quantitative EEG indicators compared to pre-treatment, with values lower than the baseline level. Such changes may suggest that neural plasticity has occurred, as it is the capacity of neurons to regulate their own excitability relative to network activity, which is observed in neurofeedback as an opposite and paradoxical change in brain activity following the training58. We must acknowledge that these results about tDCS in this study should be interpreted with caution and may require further validation in future studies. The observed reduction in QEEG indices following tDCS intervention warrants longitudinal investigation to determine its prognostic implications for long-term recovery.

This study has several limitations. First, we acknowledge the potential confounding effect of the robotic arm in the KI-BCI and BCI-tDCS groups, as the additional upper limb movements it facilitated may have contributed to the superior motor improvements observed compared to the tDCS group. While the BCI system integrates a robotic arm (an upper limb ergometer), it is crucial to note that the ergometer’s activation was contingent upon sufficiently strong motor imagery signals, establishing a closed-loop interaction between the central and peripheral nervous systems. This differs from conventional robotic training, where movement occurs in an open-loop manner without direct neural engagement. To further contextualize these findings, we reviewed relevant literature examining the effects of robotic upper limb training without BCI intervention. While some studies suggest that upper limb cycle ergometer training may enhance upper limb strength and reduce post-stroke shoulder pain59,60, However, one study61 reported that no significant additional benefits beyond conventional therapy. This suggests that the effects of robotic training on motor recovery remain inconclusive. We recognize the limitation of our study in not including a sham-BCI control group, in which the robotic arm would be activated independently of EEG signals. The inclusion of such a condition in future studies would help disentangle the specific contributions of motor imagery-driven activation versus passive robotic assistance. Second, the sample size was relatively small. Third, the limited number of EEG channels collected may have restricted the precise localization of brain activity, signal interpretation, and detailed analysis, potentially reducing the study’s statistical power. Finally, the lack of time-domain feature extraction and frequency band analysis from the EEG signals may have caused certain changes to go undetected.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that KI-BCI significantly enhances upper limb function and daily living abilities in subacute stroke patients compared to tDCS alone. While the combined BCI-tDCS intervention improved motor performance relative to tDCS, it did not yield any statistically significant advantages over KI-BCI monotherapy within the same treatment duration. Quantitative EEG revealed distinct neurophysiological trajectories: KI-BCI and BCI-tDCS groups exhibited ascending trends in neural activity, whereas tDCS showed a decline from higher baseline levels, possibly reflecting homeostatic regulation. These findings highlight KI-BCI as a promising standalone intervention and underscore the need for optimized protocols in multimodal approaches. Future research should explore dose-response relationships, long-term outcomes, and biomarker-guided strategies to maximize therapeutic efficacy.

Data availability

Due to privacy and ethical considerations, data are only available upon request by contacting the corresponding author, Tang Wei, at tangwei@cumt.edu.cn.

References

GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and National burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20(10), 795–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0 (2021).

Zhuang, J. Y., Ding, L., Shu, B. B., Chen, D. & Jia, J. Associated mirror therapy enhances motor recovery of the upper extremity and daily function after stroke: a randomized control study. Neural Plast. 2021, 7266263. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/7266263 (2021).

Ikbali Afsar, S., Mirzayev, I., Umit Yemisci, O. & Cosar Saracgil, S. N. Virtual reality in upper extremity rehabilitation of stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 27(12), 3473–3478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.08.007 (2018).

Nudo, R. J., Wise, B. M., SiFuentes, F. & Milliken, G. W. Neural substrates for the effects of rehabilitative training on motor recovery after ischemic infarct. Science 272(5269), 1791–1794. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.272.5269.1791 (1996).

Taub, E., Uswatte, G. & Elbert, T. New treatments in neurorehabilitation founded on basic research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3(3), 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn754 (2002).

Mrachacz-Kersting, N. et al. Efficient neuroplasticity induction in chronic stroke patients by an associative brain-computer interface. J. Neurophysiol. 115(3), 1410–1421. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00918.2015 (2016).

Yuan, H. & He, B. Brain-computer interfaces using sensorimotor rhythms: current state and future perspectives. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 61(5), 1425–1435. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2014.2312397 (2014).

Ibáñez, J. et al. Detection of the onset of upper-limb movements based on the combined analysis of changes in the sensorimotor rhythms and slow cortical potentials. J. Neural Eng. 11(5), 056009. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2560/11/5/056009 (2014).

Ang, K., Keng & Guan, C. Brain-computer interface in stroke rehabilitation. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 7(2), 139–146. https://doi.org/10.5626/JCSE.2013.7.2.139 (2013).

Spüler, M., ópez-Larraz, E. & Ramos-Murguialday, A. On the design of EEG-based movement decoders for completely paralyzed stroke patients. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 15, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-018-0438-z (2018).

Kevric, J. & Subasi, A. Comparison of signal decomposition methods in classification of EEG signals for motor-imagery BCI system. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control 31, 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2016.09.007 (2017).

Suefusa, K. & Tanaka, T. A comparison study of visually stimulated brain-computer and eye-tracking interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 14(3), 036009. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aa6086 (2017).

Saha, S., Ahmed, K., Mostafa, R., Hadjileontiadis, L. & Khandoker, A. Evidence of variabilities in Eeg dynamics during motor imagery-based multiclass brain-computer interface. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 26(2), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2017.2778178 (2018).

Sharma, N., Pomeroy, V. M. & Baron, J. C. Motor imagery: a backdoor to the motor system after stroke? Stroke 37(7), 1941–1952. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000226902.43357.fc (2006).

Ang, K. K. & Guan, C. J. P. I. Brain–computer interface for neurorehabilitation of upper limb after stroke. Proc. IEEE 103(6), 944–953. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2015.2415800 (2016).

Zapała, D., Augustynowicz, P. & Jankowski, T. Motor imagery perspective and brain oscillations characteristics: differences between right- and left-handers. Brain Res. Bull. 220, 111155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2024.111155 (2025).

Yu, Q. H. et al. Imagery perspective among young athletes: differentiation between external and internal visual imagery. J. Sport Health Sci. 5(2), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.12.008 (2016).

Hardy, L. & Callow, N. Efficacy of external and internal visual imagery perspectives for the enhancement of performance on tasks in which form is important. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 21(2), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.21.2.95 (1999).

Lee, W. H. et al. Target-oriented motor imagery for grasping action: different characteristics of brain activation between kinesthetic and visual imagery. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 12770. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49254-2 (2019).

Zhang, K. et al. Enhancement of capability for motor imagery using vestibular imbalance stimulation during brain computer interface. J Neural Eng. 18, 5. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ac2a6f (2021).

Marchesotti, S., Bassolino, M., Serino, A., Bleuler, H. & Blanke, O. Quantifying the role of motor imagery in brain-machine interfaces. Sci. Rep. 6, 24076. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24076 (2016).

Toriyama, H., Ushiba, J. & Ushiyama, J. Subjective vividness of kinesthetic motor imagery is associated with the similarity in magnitude of sensorimotor event-related desynchronization between motor execution and motor imagery. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12, 295. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00295 (2018).

Chase, H. W., Boudewyn, M. A., Carter, C. S. & Phillips, M. L. Transcranial direct current stimulation: a roadmap for research, from mechanism of action to clinical implementation. Mol. Psychiatry. 25(2), 397–407. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0499-9 (2020).

Navarro-López, V. et al. The long-term maintenance of upper limb motor improvements following transcranial direct current stimulation combined with rehabilitation in people with stroke: a systematic review of randomized sham-controlled trials. Sens. (Basel). 21, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21155216 (2021).

Di Pino, G. et al. Modulation of brain plasticity in stroke: a novel model for neurorehabilitation. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 10(10), 597–608. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.162 (2014).

DaSilva, A. F., Volz, M. S., Bikson, M. & Fregni, F. Electrode positioning and montage in transcranial direct current stimulation. J. Vis. Exp. 51, 2744. https://doi.org/10.3791/2744 (2011).

Baxter, B. S., Edelman, B. J., Sohrabpour, A. & He, B. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation increases bilateral directed brain connectivity during motor-imagery based brain-computer interface control. Front. Neurosci. 11, 691. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2017.00691 (2017).

Mane, R., Chouhan, T. & Guan, C. BCI for stroke rehabilitation: motor and beyond. J. Neural Eng. 17(4), 041001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aba162 (2020).

Bai, Z., Fong, K. N. K., Zhang, J. J., Chan, J. & Ting, K. H. Immediate and long-term effects of BCI-based rehabilitation of the upper extremity after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 17, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-020-00686-2 (2020).

Andersson, B. & Luo, H. The mini-mental state examination in a Chinese population: reliability, validity, and measurement invariance. Innov. Aging 7(Suppl 1), 385. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igad104.1275 (2023).

Chan, N. H. & Ng, S. S. M. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the arm activity measure in people with chronic stroke. Front. Neurol. 2023, 1248589. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1248589 (2023).

Mrachacz-Kersting, N., Ibáñez, J. & Farina, D. Towards a mechanistic approach for the development of non-invasive brain-computer interfaces for motor rehabilitation. J. Physiol. 599(9), 2361–2374. https://doi.org/10.1113/P281314 (2021).

Toro, C. et al. Event-related desynchronization and movement-related cortical potentials on the ECoG and EEG. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 93(5), 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-5597(94)90126-0 (1994).

Bai, O. et al. Prediction of human voluntary movement before it occurs. Clin. Neurophysiol. 122(2), 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2010.07.010 (2011).

Ofner, P., Schwarz, A., Pereira, J. & Müller-Putz, G. R. Upper limb movements can be decoded from the time-domain of low-frequency EEG. PLoS One. 12(8), e0182578. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182578 (2017).

Jeong, Y-S., Jeong, M. K. & Omitaomu, O. A. Weighted dynamic time warping for time series classification. Pattern Recogn. 44(9), 2231–2240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2010.09.022 (2011).

van Wijck, F. M., Pandyan, A. D., Johnson, G. R. & Barnes, M. P. Assessing motor deficits in neurological rehabilitation: patterns of instrument usage. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 15(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/154596830101500104 (2001).

Velstra, I. M., Ballert, C. S. & Cieza, A. A systematic literature review of outcome measures for upper extremity function using the international classification of functioning, disability, and health as reference. Pm R. 3(9), 846–860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.03.014 (2011).

Woytowicz, E. J. et al. Determining levels of upper extremity movement impairment by applying a cluster analysis to the fugl-meyer assessment of the upper extremity in chronic stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 98(3), 456–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.03.014 (2017).

Sánchez Cuesta, F. J. et al. Effects of motor imagery-based neurofeedback training after bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on post-stroke upper limb motor function: an exploratory crossover clinical trial. J. Rehabil Med. 56, jrm18253. https://doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v56.18253 (2024).

Wei, X. J., Tong, K. Y. & Hu, X. L. The responsiveness and correlation between fugl-meyer assessment, motor status scale, and the action research arm test in chronic stroke with upper-extremity rehabilitation robotic training. Int. J. Rehabil Res. 34(4), 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e32834d330a (2011).

Ferraro, M. et al. Assessing the motor status score: a scale for the evaluation of upper limb motor outcomes in patients after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 16(3), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/154596830201600306 (2002).

Ferfeli, S. et al. Reliability and validity of the Greek adaptation of the modified Barthel index in neurorehabilitation patients. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil Med. 60(1), 44–54. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.23.08056-5 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Dual-tDCS combined with sensorimotor training promotes upper limb function in subacute stroke patients: a randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled study. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 30(4), e14530. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.14530 (2023).

Xi, X. et al. Analysis of functional corticomuscular coupling based on multiscale transfer spectral entropy. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 26(10), 5085–5096. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2022.3193984 (2022).

Delorme, A. Makeig, S. J. & Jonm, E. EGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods. 134(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009 (2004).

Lanzone, J. et al. Quantitative measures of the resting EEG in stroke: a systematic review on clinical correlation and prognostic value. Neurol. Sci. 44(12), 4247–4261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-06981-9 (2023).

Sood, I. et al. Quantitative electroencephalography to assess post-stroke functional disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 33(12), 108032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2024.108032 (2024).

Claassen, J. et al. Quantitative continuous EEG for detecting delayed cerebral ischemia in patients with poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin. Neurophysiol. 115(12), 2699–2710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2004.06.017 (2004).

Sheorajpanday, R. V., Nagels, G., Weeren, A. J., van Putten, M. J. & De Deyn, P. P. Quantitative EEG in ischemic stroke: correlation with functional status after 6 months. Clin. Neurophysiol. 122(5), 874–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2010.07.028 (2011).

Finnigan, S. & van Putten, M. J. EEG in ischaemic stroke: quantitative EEG can uniquely inform (sub-)acute prognoses and clinical management. Clin. Neurophysiol. 124(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2012.07.003 (2013).

Ethier, C., Gallego, J. & Miller, L. E. Brain-controlled neuromuscular stimulation to drive neural plasticity and functional recovery. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 33, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2015.03.007 (2015).

Oujamaa, L., Relave, I., Froger, J., Mottet, D. & Pelissier, J-Y. Rehabilitation of arm function after stroke. Literature review. Annals Phys. Rehabilitation Med. 52(3), 269–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2008.10.003 (2009).

Daly, J. J. & Wolpaw, J. R. Brain-computer interfaces in neurological rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol. 7(11), 1032–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70223-0 (2008).

Bastani, A. & Jaberzadeh, S. Does anodal transcranial direct current stimulation enhance excitability of the motor cortex and motor function in healthy individuals and subjects with stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 123(4), 644–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2011.08.029 (2012).

Triccas, L. T. et al. A double-blinded randomised controlled trial exploring the effect of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation and uni-lateral robot therapy for the impaired upper limb in sub-acute and chronic stroke. NeuroRehabilitation 7(2), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-1512513 (2015).

Elsner, B., Kwakkel, G., Kugler, J. & Mehrholz, J. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for improving capacity in activities and arm function after stroke: a network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-017-0301-7 (2017).

Sitaram, R. et al. Closed-loop brain training: the science of neurofeedback. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18(2), 86–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70223-0 (2017).

da Rosa Pinheiro, D. R. et al. Upper limbs cycle ergometer increases muscle strength, trunk control and independence of acute stroke subjects: a randomized clinical trial. NeuroRehabilitation 48(4), 533–542. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-210022 (2021).

de Andressa, J. et al. To combine or not to combine physical therapy with tDCS for stroke with shoulder pain? Analysis from a combination randomized clinical trial for rehabilitation of painful shoulder in stroke. Front. Pain Res. 2, 696547. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpain.2021.696547 (2021).

Rabadi, M. et al. A pilot study of activity-based therapy in the arm motor recovery post stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 22(12), 1071–1082. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508095358 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Xuzhou Key Medical Talents Project (XWRCHT20220045) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.52375224).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study. ZM defined the study protocol and were responsible for patient recruitment and screening. WY and JF performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. GL and CFM coordinated the data collection and conducted the therapy sessions. TW helped with the study design and clinical implementation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ming, Z., Yu, W., Fan, J. et al. Efficacy of kinesthetic motor imagery based brain computer interface combined with tDCS on upper limb function in subacute stroke. Sci Rep 15, 11829 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96039-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96039-x