Abstract

The liquefied natural gas (LNG) floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) unit is a new type of floating production device developed for the exploitation, pretreatment, liquefaction, and storage of offshore natural gas. In this study, the shell side structure of the spiral-wound heat exchanger is analyzed, and the effects of varying the Reynolds number (Re), tube outer diameter, and number of distributors on the thickness of the shell-side liquid film are investigated. The results show that as the fluid flows down from the distributor, it hits the upper wall of the pipeline and diffuses evenly to both sides, before converging in between the two distributors. In the axial direction, the thickness of the liquid film increases first, reaches the highest at the peak, then decreases, reaches the lowest at the trough, and then increases again, forming a secondary peak at the drop. The thickness of the liquid film changes periodically, and the period is the distance between the two distributors. The thickness of the circumferential liquid film is negatively correlated with the circumferential angle, α. Moreover, the liquid film is thinnest at α = 120°, and is positively correlated with both the liquid mass flow rate and the outer diameter of the tube. The most uniform liquid film thickness is obtained when Re = 1500, the tube outer diameter is 12 mm, and the number of distributors is 6. The results from this study can guide the design of spiral-wound heat exchangers and facilitate their safe and efficient operation in natural gas liquefaction processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The low density and large volume of natural gas make it costly and inefficient to transport. Therefore, it is often converted into liquefied natural gas (LNG) prior to transportation. The liquefaction process requires the natural gas to be cooled. Currently, one of the most popular types of heat exchangers used for this purpose is the spiral-wound type, which offers many advantages such as a wide range of applicable temperatures, good heat compensation of the tube bundle, large unit heat transfer area, small heat transfer temperature difference, compact structure, low scaling tendency, and high heat transfer efficiency.

To date, spiral-wound heat exchangers have been studied extensively both in China and abroad. Many of these studies have utilized experimental methods. For example, Weiwei et al.1 studied the fluid flow and heat transfer behavior of the spiral-wound heat exchanger in the environment. The results showed that the ratio of tube spacing to diameter greatly influences the heat transfer performance, as it is positively correlated with the shell-side Nusselt number (Nu). Hui2 compared the state of domestic and foreign advancements in spiral-wound heat exchanger technology, finding that the design technology of the large heat exchanger in China was not yet mature. Moreover, there is still a gap between domestic and foreign technology in terms of material selection, surface treatment, manufacturing, and other aspects of the core and shell assembly of large spiral-wound heat exchangers. Moreover, to improve the stability and reliability of the equipment, it is also necessary to improve the technology responsible for automatic control and troubleshooting. Zhiyong et al.3 ’s research found that the spiral-wound heat exchanger has the characteristics of large heat transfer area, large temperature difference, high heat transfer coefficient and high pressure. Jiakai4 explored ways of improving the shell-side heat transfer performance of spiral-wound heat exchangers. In their experiments, the Wilson method was used to calculate the heat transfer coefficients of the shell and tube sides, and the equipment design was optimized. Tianming et al.5 found that the heat transfer efficiency of the shell side can be significantly improved by improving the diversion structure between the tubes and increasing the number of baffles on the tube. Lan et al.6 put forward that under the same working conditions, spiral-wound tube heat exchangers are safer than ordinary straight-tube heat exchangers, as their stress state is less affected by the temperature load. Wu et al.7 obtained the unstable state of the convective bomb through experiments, and showed that the flow bomb is stable when the number of supports of the spiral tube is ≥ 4, as this inhibits the formation of turbulent buffeting. Qi et al.8 found that implanting spiral wire in the heat transfer pipe can strengthen the convective heat transfer coefficients on both the compressed air and vapor sides. Moreover, the forced convection effect is strongly positively correlated with the air flow rate. Qi et al.9 found that increasing the inlet flow rate only has a small impact on the outlet temperature. Moreover, there is a swirl phenomenon in the inner wall of the tube, which enhances heat transfer by destroying the boundary layer between the liquid and the tube wall. Yaolong et al.10 concluded that in the absence of a distributor, the air quality remains unchanged, and that the single-phase dispersion coefficient is independent of the total mass flow rate. However, in general, the two-phase dispersion coefficient is smaller than its single-phase counterpart. For two-phase gas–liquid mixtures, the dispersion coefficient normally shows a minimum value with decreasing air humidity. Gao et al.11 successfully successfully realized the localization of ultra-long seamless aluminum alloy tubes. This marks another breakthrough in the localization of LNG spiral-wound heat exchanger technology in China, and fills the gap in this field at home and abroad.

Apart from experimental methods, numerical simulations have also been extensively employed to study spiral-wound heat exchangers. For example, Yin et al.12 modeled the temperature distribution in spiral-wound heat exchanger tubes and validated the model using real experimental data. Jia13 conducted a large number of experimental studies on the geometric parameters affecting the heat transfer characteristics of heat exchange tubes, such as the tube diameter and spiral winding angle. They concluded that the smaller the pipe diameter, the less it influences heat transfer, and that the heat transfer is largely unaffected by the spiral winding angle. Jinxing et al.14 established a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model of the spiral-wound heat exchanger using Ansys Fluent software. Their results showed that the best heat transfer on the shell side is obtained when the aperture is 6 mm, the axial spacing is 14 mm, and the lateral spacing is 35 mm. Peng15 analyzed the influence of shell-side structural parameters on the tube-side heat transfer coefficient of the spiral-wound heat exchanger. They found that reducing the thickness of the gasket can increase the tube-side heat transfer coefficient by producing greater turbulence in the shell-side fluid. Moreover, when the Reynolds number (Re) is constant, the heat transfer coefficient on the tube side is negatively correlated with the inner diameter of the tube. Qiu et al.16 found that when the propane mass flow rate is ≤ 250 kg/(m2·s), only small amounts of stratified flow and mist flow occur, resulting in relatively stable operation. However, when the propane mass flow rate is > 350 kg/(m2·s), the occurrence of stratified, annular, and mist flow is positively correlated with the mass flow rate. Moreover, the heat transfer coefficient and pressure drop obtained by the model were in good agreement with the results obtained using the classical correlation. Jiangtao et al.17 showed that both the diameter ratio and the circumferential ratio are negatively correlated with the heat transfer coefficient. Moreover, the value of the winding tube angle also affects the heat transfer efficiency. Qixiong et al.18 simulated the heat transfer characteristics of the inner flow for different shapes of the tube-wound heat exchanger shell. Qin et al.19 studied the three-layer wound tube heat exchanger, finding that increasing the diameter of the heat exchange tube, the inlet velocity, and the winding angle can all increase the heat transfer coefficient; however, these effects plateau out after reaching a certain value. Songbo et al.20 simulated the shell-side heat transfer of the spiral-wound heat exchanger with liquid water as the medium. They found that the heat transfer conditions of the shell side are functions of the tube length and diameter. In particular, the heat transfer coefficient shows a minimum value with increasing tube length while gradually decreasing with increasing tube diameter. Longfei et al.21 showed that the heat transfer coefficient of the shell side and the pressure drop of the shell side coolant are positively correlated with the diameter of the heat exchange tube and the mass flow rate of the shell side coolant. Wu et al.22 found that when the pipe diameter is 6 mm, the layer spacing is 3.5 mm, and the axial spacing is 14 mm, the comprehensive heat transfer performance evaluation factor has a maximum value, and the temperature difference and pressure drop simulation results differ from the experimental data by 1–4 °C, 0.8–1.2 kPa. Xinghui et al.23 found that the Nusselt number of the shell side increases with the increase of Reynolds number, and the drag coefficient f decreases linearly. The Nusselt number of the shell side increases with the increase of the diameter d of the winding pipe and the average winding diameter D, and decreases with the increase of the pitch S, while the drag coefficient f is the opposite. Zengfa et al.24 found that as the Reynolds number increases, the flow Nusselt coefficient of the shell side increases, and the comprehensive heat transfer performance is improved, while the flow resistance coefficient is basically unchanged. Laiyun et al.25 found that when the dryness is constant, the mass flow distribution of the two-phase refrigerant fluid on the shell side of the tube-wound heat exchanger is more balanced at higher flow rates; however, this effect is more pronounced when the dryness is < 0.5, before plateauing out subsequently. Xiao26 found that when the dryness is constant, if the Reynolds number is larger, the heat transfer effect on the inner side of the spiral-wound heat exchanger shell will be better and better. When the Reynolds number is constant, the number of degrees is increasing, and the heat transfer effect of the spiral-wound heat exchanger will be worse and worse. However, if the dryness is increased to a certain value, the heat transfer effect will be reduced. Chen et al.27 found that, all else being equal, a very high flow rate of the low-temperature refrigerant on the shell side weakens the heat transfer effect of the spiral-wound heat exchanger. Conversely, increasing the inclination angle within a certain range increases the heat transfer effect, as does increasing the diameter of the tubes and the distance between them. Dong et al.28 found that increasing the aperture of the spoiler element causes the Nu and friction factor, f, of the high-viscosity medium to gradually decrease. However, both these variables show maximum values with increasing pin length of the spoiler. Moreover, the overall heat transfer performance of the heat exchanger is negatively correlated with the diameter of the spoiler and positively correlated with its length. Through finite element calculation, Xiaohui et al.29 found that the thickening treatment of the connection between the central cylinder and the cylinder can meet the material strength requirements. Lin et al.30 found that under a given set of working conditions, the heat transfer coefficient is initially negatively correlated with the dryness before plateauing when the dryness reaches 0.7. In addition, increasing the mass flow density has a significant strengthening effect on heat transfer. Zhao et al.31 comprehensively reviewed the correlation between flow mode transition, film thickness, heat transfer and liquid film rupture in falling film flow on horizontal tubes and tube bundles. Avijit et al.32 studied the hydrodynamic behavior of the falling film on the horizontal circular tube. It was found that in the droplet mode, the droplet impacts the tube to produce liquid waves. These liquid waves interact with adjacent waves and can propagate in the area between the tube surface and the impact point downstream of the impact area. The movement of these waves results in a significant change in the film thickness on the surface of the tube within a short interval of the droplet mode cycle, exceeding 350% in number.

Against this backdrop, the present study uses a numerical simulation approach to investigate the effects of varying structural parameters such as the number of distributors, the tube diameter, and Re on the shell-side liquid film thickness of the spiral-wound heat exchanger. The main contents of this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

The current state of research on spiral-wound heat exchangers at home and abroad is summarized.

-

(2)

An appropriate geometric model of the shell side of the spiral-wound heat exchanger is selected for the numerical simulations and the optimum number of mesh elements is obtained through grid independence testing.

-

(3)

The effects of different structural parameters such as the number of distributors, different Reynolds numbers and different tube diameters on the distribution of liquid film thickness on the shell side of the spiral-wound heat exchanger were simulated.

Model description

Governing equations

The continuity equation is as follows:

where ρ is the fluid density (kg/m3), τ is time (s), u and v are the fluid velocities in the x- and y- directions, respectively (m/s), and SM is the added source term (kg/(m3·s)).

The momentum conservation equation is expressed as follows:

where fi is the mass force of the fluid element (N), and σij is the stress on each surface of the micro-element (Pa). The subscripts i and j refer to different directions.

The gas–liquid two-phase momentum equation is as follows:

The surface tension equations are as follows:

where the subscripts 1 and 2 represent the gas and liquid phases, respectively, σ is the surface tension coefficient of the two-phase gas–liquid mixture (N/m), k is the surface curvature of the second phase, and \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\smile}$}}{n}\) is the unit normal vector.

The parameters of mass flow per unit length and the thickness of liquid film are defined as follows:

and

The dimensionless numbers Pr and Re are defined as follows:

and

where Q is the liquid mass flow rate per unit tube length, kg/(m·s); S is the tube spacing, m; D is the outer diameter of the tube, m; c and n are constants which vary with α, α is the circumferential angle, and the subscripts 1 and 2 represent the gas and liquid phases, respectively. m1 is the mass flow, m; Xtube is the length of tube, m and μ is the dynamic viscosity, N·s·m−2.

Geometric model of spiral-wound heat exchanger

Through analysis and optimization of the shell-side structure of the spiral-wound heat exchanger, a shell-side geometric model with dimensions of 64 × 20 × 40 mm (length × width × height) was constructed, as shown in Fig. 1 (where S is the spacing of the heat exchange tubes and α is the circumferential angle). The spacing between the upper surface of the first heat exchange tube and the distributor is 6 mm, as is spacing between the lower surface of the second tube and the outlet. The model contains five distributors, four of which are square in shape (with side lengths of 2 mm) and located in the middle. The remaining two distributors are 2 × 1 mm rectangles which are symmetrically arranged on the left and right sides. The specific structural parameters are shown in (Table 1).

Using the structured grid drawing method implemented in CFD software, the geometric model was meshed, as illustrated in (Fig. 2). In order to capture the phenomenon of falling film flow, the mesh was encrypted around the liquid inlet and the shell-side tube. In the first layer of the grid near the surface of the heat exchange tube, the maximum grid size was set to 0.02 mm. The maximum mesh size was set to 0.5 mm at the positions located furthest away from the surface of the heat exchange tube.

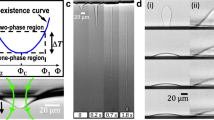

Grid independence testing

The numerical simulations utilized the VOF multiphase flow and the continuous surface tension models with a time step of 10−5 s and a maximum of 100 iteration steps. The pressure–velocity coupling method is used in the numerical model, and the PISO (Pressure Implicit with Splitting of Operators) algorithm is selected. The QUICK method is used to discretize the momentum equation space, and the PRESTO! is used to discretize the pressure. The volume fraction was calculated by Geo-Reconstruct method, and the Level Set was calculated by QUICK method. In the process of numerical simulation, pentane is selected as the flow medium, mainly based on its physical properties at room temperature (25℃). Compared with water and ethanol, the density (620.7 kg/m3) and viscosity (0.2204 mPa·s) of pentane are more similar to the physical parameters of the liquid phase mixed refrigerant at low temperature (−127.3℃) in the mixed refrigerant natural gas liquefaction process. The density of the latter is 571.0 kg/m3 and the viscosity is 0.2535mPa·s. Under the action of gravity, the working fluid on the shell side is ejected from the spray distributor and forms a liquid film on the surface of the heat exchange tube. This film spreads along the axial and circumferential directions of the heat exchange tube and gathers in between the two distributors to form a peak, before forming a columnar flow, as shown in (Fig. 3). The simulation results of the top wave crest, the bottom liquid belly and the flow characteristics between tubes of the falling film flow are basically consistent with Sun’s33 experimental results. For grid independence testing, the liquid film thickness was calculated as a function of the circumferential angle of the heat exchange tube for different numbers of grid elements (Fig. 4). The results show that when the number of elements exceeds 920,000, the variation in calculated liquid film thickness is within 5%. Therefore, as a tradeoff between simulation accuracy and computational time, 920,000 was chosen as the optimum grid number.

Simulation results and discussion

Reynolds number

In order to study the influence of Re on the shell-side flow of the spiral-wound heat exchanger, the shell-side falling film flow was simulated for Re = 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000, respectively (Fig. 5). The results show that the shell-side coolant falls vertically from the distributor in the form of a liquid column and diffuses in both the axial and circumferential directions after hitting the tube wall. The refrigerant diffuses to both sides of the shell, forming a peak in the middle of the two distributors, and there is a significant peak area and a stable area in the liquid film distribution outside the first tube. The liquid film distribution outside the second tube was similar to that in the first tube. The liquid began to flow downward from the aggregation point, forming a trough area in the second tube. In between the two distributors, the liquid film thickens, and there is a peak area in the middle, which oscillates along the axial direction. For Re = 500, the liquid film does not reach between the two distributors, and therefore does not completely coat the heat exchange pipeline. As Re increases to 1000, the liquid film distinctly converges in the middle of the two distributors, causing the liquid column to become noticeably thicker and to fully coat the heat exchange tube. This trend intensifies at Re = 1500, with the liquid film exhibiting a clearly visible peak between the two distributors, and the liquid column also changes from a column to a column flow with a downward splash. For Re = 2000, the liquid film not only oscillates between the two distributors, but the liquid column also transitions to flaky columnar flow.

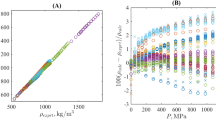

Figure 6 shows the axial variation of the liquid film thickness under different Re values at α = 45°, whence it can be seen that the liquid film thickness follows a similar trend at different Re. The refrigerant flowing from the distributor diffuses evenly on both sides after hitting the upper wall of the pipeline, eventually converging in the center to produce the main peak. The secondary peak is formed at the drop position below the distributor. At this position, the liquid film thickness is positively correlated with Re. This is because both the shell-side space pressure outside the heat exchange tube and the residence time of the shell-side coolant on the heat exchange tube remain basically unchanged. Therefore, the shell-side liquid film thickness is positively correlated with the mass flow rate. For Re = 500, 1000, 1500 and 2000, the maximum thicknesses of the main peaks are 0.379, 0.427, 0.539, and 0.774 mm, respectively, while those of the secondary peaks are 0.288, 0.269, 0.258, and 0.233 mm, respectively. Overall, when Re increases from 500 to 1000, the liquid film thickness increases by 32.25% on average. The corresponding average increases in film thickness when Re increases from 1000 to 1500 and from 1500 to 2000 are 7.09 and 21.44%, respectively.

Figure 7 shows the circumferential variation of the liquid film thickness on the shell side of the tube-wound heat exchanger at different Re. First, the refrigerant slowly flows out of the distributor towards the upper edge of the heat exchange pipe, before flowing downward to coat the entire pipe. Finally, it converges at the bottom of the pipe and flows downward again to form a liquid column. The results show that under different Re, the liquid film thickness shows a minimum value with increasing α. Overall, when Re increases from 500 to 1000, the film thickness increases by 10.19% on average. The corresponding average increases in film thickness when Re increases from 1000 to 1500 and from 1500 to 2000 are 19.46 and 3.42%, respectively.

Diameter of heat exchange tube

In order to study the influence of pipe diameter on the shell-side flow of the spiral-wound heat exchanger, the shell-side falling film flow was simulated at pipe diameters of 6, 8, 10, and 12 mm, respectively, for α = 45°. Figure 8 shows the resulting liquid film thicknesses along the axial direction whence it can be seen that the axial liquid film thickness follows a similar trend under different pipe diameters. Moreover, the thickness of the liquid film shows a periodic change, with the change period being equal to the distance between the two distributors. Taking the region between the two distributors as an example, the thickness of the liquid film initially increases along the axial direction, reaching a maximum at the peak. There is a trough between the peak and the distributor, and there is a secondary peak at the distributor. At a given axial position, the thickness of the liquid film is positively correlated with the pipe diameter. For pipe diameter values of 6, 8, 10, and 12 mm, the maximum thicknesses of the main peaks are 0.539, 0.736, 0.906 and 0.941 mm, respectively, while those of the secondary peaks are 0.235, 0.245, 0.270, and 0.287 mm, respectively. Overall, when the pipe diameter increases from 6 to 8 mm, the liquid film thickness increases by 12.19% on average. The corresponding average increases in film thickness when the diameter increases from 8 to 10 mm and from 10 to 12 mm are 52.16 and 1.86%, respectively.

Figure 9 shows the circumferential variation of the liquid film thickness under different pipe diameters. The liquid first slowly flows from the distributor to the upper edge of the heat exchange pipe, then flows downwards to coat the entire pipe. Finally, the liquid re-converges at the bottom of the pipe and flows downwards again to form a liquid column. As α increases, the film thickness gradually decreases. Overall, when the pipe diameter increases from 6 to 8 mm, the liquid film thickness increases by 4.62% on average. The corresponding average increases in film thickness when the pipe diameter changes from 8 to 10 mm and from 10 to 12 mm are 4.85 and 4.55%, respectively.

Number of distributors

In order to study the influence of the number of distributors on the shell-side flow of the spiral-wound heat exchanger, the shell-side falling film flow was simulated with 5, 6, 7, and 8 distributors, respectively, for α = 45°. Figure 10 shows the resulting axial variation of the liquid film thickness, whence it can be seen that the liquid film thickness follows a similar trend at different numbers of distributors. For the cases with 5, 6,7, and 8 distributors, the maximum thicknesses of the main peaks are 0.539, 0.891, 0.854, and 0.773 mm, respectively, while those of the secondary peaks are 0.235, 0.300, 0.280, and 0.250 mm, respectively. Overall, when the number of distributors increases from 5 to 6, the liquid film thickness of the spiral-wound heat exchanger increases by 37.91% on average; however, when the number of distributors increases from 6 to 7 and from 7 to 8, the liquid film thickness shows average decreases of 8.57 and 13.94%, respectively.

Figure 11 shows the circumferential variation of the liquid film thickness for different numbers of distributors. The results show that the liquid film thickness follows a similar trend at different numbers of distributors, exhibiting a minimum value at α = 120°. Moreover, at a given value of α, the liquid film thickness is largest when the number of distributors is 6. Overall, when the number of distributors increases from 5 to 6, the liquid film thickness of the spiral wound heat exchanger increases by 27.15% on average; however, when the number of distributors increases from 6 to 7 and from 7 to 8, the liquid film thickness shows average decreases of 9.64 and 5.15%, respectively.

Conclusions

In this paper, a geometric model of the shell side of the spiral-wound heat exchanger was established using three-dimensional modeling software. A structured meshing method was used and the mesh was locally encrypted. The variation of the shell-side liquid film thickness under different Re values, tube outer diameters, and numbers of distributors was simulated. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The shell-side coolant falls vertically from the distributor as a liquid column and diffuses axially and circumferentially after hitting the tube wall. The refrigerant diffuses to both sides after impacting the heat exchange tube, forming a peak in the middle of the two distributors, and there is a significant peak area and a stable area in the liquid film distribution outside the first tube. The liquid film distribution outside the second tube was similar to that in the first tube. The liquid began to flow downward from the aggregation point, forming a trough area in the second tube. In between the two distributors, the liquid film is thicker, and oscillates along the axial direction. The liquid film is thinnest at α = 120°.

-

(2)

As Re increases, the axial and circumferential liquid film thicknesses on the outer wall of the heat exchange tube both increase. As Re increases from 1000 to 1500, these thicknesses show average increases of 7.09% and 19.46%, respectively. Under these conditions, the refrigerant fully coats the outer wall of the heat exchange tube, and the liquid film thickness is moderate, which is conducive to heat transfer.

-

(3)

As the outer diameter of the tube increases, the axial and circumferential liquid film thicknesses on the outer wall of the heat exchange tube also increase. When the outer diameter of the tube is between 10 and 12 mm, a thin, even liquid film coats the outside surface of the tube wall, and the flow pattern between the tubes is stable.

-

(4)

At a given α, when the number of distributors is 6, the liquid film is thickest, and the pipeline is fully encapsulated by the liquid.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Li, W. W. Study on Heat Transfer Enhancement in Shell Side of Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger (Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 2007).

Pu, H. & Chen, J. Application of coiled tube heat exchanger in large-scale natural gas liquefaction plant and analysis of domestic technology. Chinese J. Refrigerat. Technol. 31 (03), 26–29 (2011).

Wu, Z. Y. et al. Numerical simulation of superheated flow on shell side of LNG spiral wound heat exchanger. Gas Heat 34 (08), 6–11 (2014).

Zhang, J. K. et al. Research progress of spiral wound heat exchanger in LNG industry. Appl. Chem. Ind. 49 (10), 2586–2589 (2020).

Zhong, T. M. et al. Research progress on heat transfer of spiral wound tube heat exchanger. Chem. Eng. Oil Gas 45 (03), 120–127 (2020).

Min, L. et al. Finite element stress analysis of spiral wound tube heat exchanger based on ANSYS workbench. Chem. Eng. Equip. 02, 185–198 (2020).

Wu, J. B. et al. Study on flow-induced vibration of spiral tube heat exchanger. Atomic Energy Sci. Technol. 54 (02), 250–256 (2020).

Qi, J. et al. Study on heat transfer coefficient of tube heat exchanger. J. Dalian Minzu Univ. 23 (01), 1–30 (2021).

Xu, Q. et al. Analysis of fluid flow and heat transfer performance of spiral wound tube heat exchanger. Energy Res. Manag. 04, 122–128 (2022).

Wang, Y. L. et al. Effect of distributor on shell-side fluid of LNG spiral wound heat exchanger. Gas Heat 42 (05), 16–32 (2022).

Gao, W. et al. Research and development of ultra-long seamless aluminum alloy tube series for LNG spiral wound heat exchanger. Modern Chem. Res. 04, 165–167 (2022).

Yin, J. X. et al. Heat transfer model and experiment of winding tube heat exchanger. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci.Technol.) (06): 73–75+79 (2000).

Jia, J. C. Numerical study on the influence of geometric parameters on the heat transfer characteristics of spiral wound heat exchanger. Fluid Mach. 39 (08), 33–37 (2011).

Wu, J. X. et al. Structure analysis and application prospect of coiled tube heat exchanger. Pressure Vessel Technol. 31 (02), 38–42 (2014).

Ji, P. et al. Influence of structural parameters on heat transfer characteristics of spirally wound heat exchanger. Oil Gas Storage Transport. 34 (08), 886–891 (2015).

Qiu, G. D. et al. Simulation of two-phase flow condensation heat transfer and pressure drop along the coil-wound heat exchanger. Gas Heat 35 (02), 44–48 (2015).

Wei, J. T. & Zeng, T. Numerical study on shell-side heat transfer characteristics of spiral wound tube heat exchanger. Chem. Eng. Equip. 02, 21–23 (2015).

Tang, Q. X. et al. Experiment and numerical simulation of shell-side gas flow in spirally wound heat exchanger. Cryogenics (05): 1–5+11 (2017).

Li, Q., Zhang, Z. K. & He, P. F. Optimization design and numerical simulation of heat transfer of spiral wound tube heat exchanger. Chem. Eng. Design Commun. 44(10), 119–121 (2018).

Liu, S. B. Analysis of research status of spiral wound tube heat exchanger. Intern. Combust. Engine Parts 11, 222–223 (2018).

Dong, L. F., Li, Y. X. & Han, H. Numerical simulation of convective heat transfer in shell side of LNG spiral-wound heat exchanger. Oil Gas Storage Transportat. 38 (06), 697–703 (2019).

Wu, J. X., Liu, S. L. & Peng, X. Simulation and experimental study on shell-side flow and heat transfer of spiral wound heat exchanger. J. Zhengzhou Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 40 (01), 77–82 (2019).

Gao, X. H., Zhou, G. Y. & Tu, S. D. Analysis of influencing factors on shell-side enhanced heat transfer performance of spiral wound heat exchanger. CIESC J. 70 (07), 2456–2471 (2019).

Wu, Z. F., Xu, H. & Xu, P. Numerical study on flow and heat transfer of shell-side parameters of spiral wound heat exchanger. Chem. Eng. (China) 47 (09), 12–17 (2019).

Lu, L. Y. et al. Simulation study on refrigerant fluid distribution performance of shell side of spiral wound heat exchanger. Energy Conserv. Technol. 38 (05), 476–481 (2020).

Wu, X. Study on shell-side heat transfer characteristics of LNG spiral wound heat exchanger. Guangzhou Chem. Ind. 49 (17), 152–154 (2021).

Hao, C. et al. Study on shell-side heat transfer characteristics of LNG spiral wound heat exchanger. Shandong Chem. Ind. 51 (16), 203–205 (2022).

Duan, X. D., Wen, J. & Wang, S. M. Study on the flow and heat transfer performance enhancement of high viscosity fluid in the shell side of spiral wound tube heat exchanger. J. Chem. Eng. Chinese Univ. 36 (05), 639–646 (2022).

Zhang, X. M. et al. Numerical simulation calculation of local structural strength of coiled tube heat exchanger. Energy Energy Conserv. 01, 58–60 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Flow and heat transfer characteristics of mixed refrigerant on shell side of LNG spiral-wound heat exchanger. Chem. Ind. Eng. 2023,42(09):4496-4503.

Zhao, C. Y. et al. Correlations of falling film hydrodynamics and heat transfer on horizontal tubes: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 197, 0364–1364 (2024).

Avijit, K., Sumanta. A. Numerical simulation of falling film flow hydrodynamics over round horizontal tubes. Int. J. Heat and Mass Trans. 2021173 121175 0017–9310.

Sun, C. Z. et al. Numerical simulation of flow characteristics of falling film outside coolant pipelines during liquefaction of natural gas. Oil Gas Storage Transport. 41 (02), 200–210 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Dongying, China (Grant No. 2023ZR04), the Science Development Funding Program of Dongying of China (Grant No. DJ2023004) and Dongying City Science and Technology Innovation Major Project (Science and Technology Development Guidance Scheme) (Grant No. 2024ZDJH75).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, L., Zhang, R. Numerical study on falling film flow outside the refrigerant tube. Sci Rep 15, 11952 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96057-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96057-9