Abstract

Due to the uncertainty existing in the actual industrial environment, the rolling bearing compound fault features present coupling and complexity, which brings challenges to the compound fault feature extraction. To address this problem, this paper proposes a rolling bearing compound fault diagnosis method AMOMCKD-CNN based on adaptive multi-objective maximum correlation kurtosis deconvolution (AMOMCKD) and convolutional neural network (CNN) with parameter optimization. Firstly, the key parameters of MCKD are optimized using the adaptive Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II) with a new multi-objective evaluation index Hyperarea (HA). Secondly, the optimized MCKD is used as a filter to extract the periodic pulse characteristics of the original vibration acceleration signal. Finally, the kernel size of the CNN is optimized based on the length of the filtered periodic pulse signal, which enables the CNN to achieve deeper feature extraction and classification. Experimental results from two different datasets highlight that AMOMCKD-CNN outperforms other classical diagnostic methods under the same conditions, and it is more conducive to the detection of compound faults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rolling bearing, as a crucial component in large rotating machinery systems, is susceptible to adverse working conditions and significant loads. For example, high-temperature environments can cause bearing material deformation and lubrication deficiencies, while strong vibrations can lead to multiple wear, cracks, and fatigue of the bearing. These compound failures result in further operational failures, economic losses, and safety hazards. Compared with single bearing component failures, vibration acceleration signals in compound failures are usually accompanied by strong noise, more significant nonlinear features, and more severe harmonic distortion1. As a result, the weak repetitive transient pulses representing the early faults are overwhelmed by the background noise interference, and the weaker transient pulse features are difficult to extract. Therefore, scientific and effective monitoring and diagnostic means are necessary for such multisite compound faults2. Comprehensive, real-time, and accurate monitoring and diagnosis of rolling bearings will help to promptly detect potential faults, improve the availability and reliability of equipment, and ensure their safe and stable operation3,4.

There are many methods for compound bearing fault diagnosis (CBFD), among them, the vibration signal-based analysis method is a more reliable way for CBFD5. The traditional CBFD process consists of three steps: signal processing, feature extraction, and pattern classification6. At the stage of signal processing, the vibration acceleration signals collected are pretreated to eliminate noise interference and improve the quality and reliability of the data. Then, the feature extraction stage captures characteristic information from the preprocessed signal, which can accurately reflect the compound failure mode and provide strong support for further classification. Finally, in the pattern classification stage, according to the characteristic information extracted, the fault classification is carried out accurately to ensure the accurate identification and determination of the fault types.

Signal processing is the first key step in CBFD, which has an important impact on the subsequent fault diagnosis. The commonly used signal processing methods mainly include wavelet transform (WT), empirical modal decomposition (EMD), and variational modal decomposition (VMD)7,8,9. However, when the vibration acceleration signal is affected by the compound fault, the above signal decomposition methods cannot effectively capture the weak transient pulse in the noise environment10,11. In fact, the fault signal can be considered as the result of the convolution between the periodic fault transient impulses and the transmission path of the bearing system (the impulse response function) added to the background noise12. The minimal entropy deconvolution (MED) technique ingeniously addresses the limitations of prior signal decomposition techniques, particularly in terms of failing to isolate transient fault impulses. It significantly mitigates the impact of the transmission path by implementing a deconvolution operation on the compound fault signal, thereby enhancing the fault diagnosis effectiveness13. However, MED targets the kurtosis function and extracts a single transient pulse without considering the periodicity of the fault pulse14. To overcome the limitations of MED in dealing with compound faults and effectively isolate periodic pulse fault components, Mcdonald et al.15 proposed an improved minimum entropy inverse plethysmography method, called maximum correlation kurtosis deconvolution (MCKD). Unlike MED, MCKD considers the periodic pulse components in vibration signals, using maximum correlation kurtosis as the filter index. It requires setting key parameters like filter length L and fault cycle T, which influence frequency and time resolution respectively. The correct selection of key parameters can balance the time resolution with the frequency resolution, which determines the success rate of extracting a single fault signal from a compound fault signal, and ultimately affects the effectiveness of compound fault diagnosis of bearings. However, the precise parameter alignment and resampling required by MCKD limit its practical application16. To address this, adaptive optimization of MCKD parameters using intelligent algorithms is crucial.

In recent years, various optimization algorithms have been combined with the MCKD method to optimize the key parameters L and T to better extract compound fault characteristics. Hu et al.17 proposed an adaptive MCKD compound fault diagnosis method for rolling bearings, which uses the spectral correlation kurtosis value of the envelope spectrum of the signal as the objective function, and utilizes an artificial fish swarm algorithm to adaptively obtain parameters L and T of the MCKD. Cui et al.18 proposed a fault diagnosis method based on VMD and MCKD, which decomposed the rolling bearing vibration acceleration signal into a series of intrinsic modal functions (IMFs) and identified the inverse pleated product parameter period T using the kurtosis criterion. This criterion was applied to determine the number of modes containing salient fault information. At the same time, Qi et al.19 proposed a particle swarm algorithm to optimize the MCKD parameters L and T for different fault types, addressing the numerous compound faults in complex operating environments. However, the fitness function of the optimization methods in previous studies only relies on a single kurtosis index of the signal. Kurtosis primarily focuses on individual prominent transient impulses, potentially overlooking other significant features of neighboring distributions, which limits comprehensive feature extraction and analysis. By contrast, as a measure of the global characteristics of a signal, envelope entropy effectively addresses the limitations of kurtosis and its sensitivity to noise. Therefore, the use of kurtosis and envelope entropy as a multi-objective fitness function can provide more information for vibration acceleration signal processing. Considering the excellent performance of the Non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II) in multi-objective optimization, especially bi-objective optimization20, this paper combines the power of NSGA-II with the advantages of the MCKD method in the bi-objective global optimization and adaptively selects the key parameters L and T of the filter using NSGA-II.

In the field of feature extraction and pattern recognition, CNN has achieved great success in making classification tasks in CBFD easier, by learning higher-order representations of data to better distinguish between different types of fault modes21,22,23. Udmale, Sandeep S., et al. use CNN with kurtogram-transformed multi-sensor data for effective fault classification of rotating machinery, with superior performance over traditional methods24,25. However, the structural design of CNNs is empirically defined and lacks interpretability. Pang et al. proposed a novel interpretable lightweight 1DCNN (ELCNN) diagnostic model that exhibits unique interpretability by constructing a single-layer CNN specialized for 1D vibration signals26. Shafin et al. achieve the interpretability of multiple machine learning models by combining the global interpretation SHAP and local interpretation LIME methods to validate the importance of these features from an individual sample perspective27. Vibration acceleration signals contain rich fault information. Optimizing CNN structures to align with signal characteristics not only enhances fault feature extraction but also improves model interpretability. In recent years, scholars have achieved good results in fault diagnosis by improving kernel size in CNN. Li et al.28 proposed an end-to-end adaptive multi-scale full convolution network, pointing out that the size of the first convolutional layer kernel has a great influence on bearing fault diagnosis. Mohammad et al.29 proposed an evolutionary integrated CNN for fault diagnosis and emphasized that the kernel size in CNN significantly influences the algorithm’s performance. Ruan et al.30 improved CNN’s original convolution kernel 3\(\times \)3, 5\(\times \)5 design based on the physical properties of the bearing vibration acceleration signal, using a targeted rectangular receiving field design to avoid the time-consuming convolutional kernel size optimization process. However, the aforementioned literature fails to filter the signal to obtain periodic pulses that are more beneficial for the CNN kernel to extract features. Theoretically, further filtering of the signal can enhance periodic pulse features, which provides more effective guidance for the design of the CNN kernel size.

To sum up, this paper combines the NSGA-II optimized MCKD method with CNN to propose the AMOMCKD-CNN method, which aims to reduce the burden of the CNN learning process by using more significant signals from the filtered periodic impulses to improve the classification accuracy of the CNN and make CBFD more effective. The innovative contributions of this paper are as follows:

1. A CBFD method (AMOMCKD-CNN) based on parameter optimization is proposed, in which the optimized MCKD algorithm is utilized to adaptively enhance faulty impulse signals, thereby improving the feature learning capability of CNNs. This innovation provides a new perspective for data-driven fault diagnosis.

2. The multi-objective evaluation index HA is innovatively integrated into the NSGA-II algorithm to adaptively select the optimal solution. In this approach, kurtosis and envelope entropy are combined into a single bi-objective fitness function, and the L and T parameters of MCKD are optimized, significantly improving the efficiency of faulty impulse extraction.

3. Based on the filtered periodic pulse characteristics, a new kernel size optimization strategy for CNN is developed to achieve more accurate compound fault feature extraction and classification. Additionally, feature visualization of CNN channels is employed to assess the effectiveness of periodic pulse extraction and to intuitively demonstrate the importance of optimized kernel sizes for different faulty impulses, thereby enhancing the interpretability of the model.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: the second part introduces the principle of MCKD and NSGA-II. The third part describes the proposed AMOMCKD-CNN method. The fourth part carries on a deconvolution experiment and analyzes the final classification results. The last part is the summary and discussion of this paper.

MCKD and NSGA-II

Maximum correlated Kurtosis deconvolution

MCKD highlights continuous pulses submerged in noise by deconvolution operations, increasing the correlation kurtosis value of the original signal. A finite impulse response (FIR) filter for vibration acceleration signal is designed and the optimal parameters are established to realize an iterative process. The actual acquired vibration acceleration signal \(x_n\) can be expressed as Eq. (1):

where \(y_n\) is the signal with more pronounced periodic impulsivity, \(h_n\) is the response of \(y_n\) through resonance as well as the surrounding noise environment, and e is the noise.

The steps of the algorithm are as follows:

(1) The MCKD algorithm essentially deconvolutes \(y_n\) from the acquired fault vibration acceleration signal \(x_n\), expressed in Eq. (2):

where \( f=[f_1,f_2,f_3...f_L]^{T}\) are the FIR filter coefficients of length L.

(2) The algorithm incorporates the correlated kurtosis, which addresses the issue of traditional indexes being overly sensitive to individual pulses by introducing the fault cycle parameter, denoted as T. The calculation formula for the correlated kurtosis is provided as Eq. (3):

Where N denotes the length of the collected vibration acceleration signal, M denotes the number of shifts of the filter, and \(T_n\) stands for the sampling points within the fault cycle T. The calculation formula for T is provided as Eq. (4):

Where \(f_o\) denotes the fault characteristic frequency, and \(f_s\) represents the sampling frequency.

(3) The algorithm’s ultimate is to maximize the correlated kurtosis of the filtered signal \(y_n\), denoted as CK by Eq. (5):

The Eq. (5) can be equivalently expressed as Eq. (6):

Expressing the equation in matrix form and rearranging yields by Eq. (7):

In the Eq. (7):

(4) The filter coefficients can thus be represented as Eq. (8):

Substituting the iterated filter coefficients into Eq. (2) yields the filtered impulse signal \(y_n\).

NSGA-II

The NSGA-II is an extension of the genetic algorithm and is widely utilized in benchmark testing of multi-objective evolutionary algorithms to find optimal solutions in multi-objective conflict. It is based on the concepts of non-dominated sorting and crowding distance and constantly develops the solution set by maintaining non-dominated solutions and employing a variety of selective operations. The principle of the main loop is shown in Fig. 1.

-

(1)

The current population \(P^t\) is selected, crossover, and mutated to produce an offspring \(R^t\) with the same number of individuals as its offspring, and at the same time, \(P^t\) is merged with \(R^t\).

-

(2)

Fast non-dominated sorting of the merged populations, where \(F_1,F_2\),...\(F_n\) denotes the subpopulations that pass the non-dominated sorting. \(F_1\) is the set of non-dominated individuals in the population, \(F_2\) is the set of non-dominated individuals in the population after the exclusion of \(F_1\), and so on

-

(3)

According to the dominance rank order, individuals of each rank are sequentially added to the next population \(P^{t+1}\) until the current rank’s individuals cannot all be accommodated. This is illustrated by the inability to include all individuals from \(F_3\) in Fig. 1.

-

(4)

The individuals of the current rank (denoted as \(F_3\) in Fig. 1) are sorted based on their crowding distances. Individuals with larger crowding distances are sequentially added to the next population \(P^{t+1}\). At this point, the remaining solutions are all eliminated. This process continues iteratively until reaching the termination condition.

The solution to the multi-objective minimization problem obtained by NSGA-II is called the non-dominated solution, also known as the pareto front. To determine the optimal solution, a multi-objective fitness function evaluation is necessary. Andreia P. Guerreiro demonstrated in research on stochastic multi-objective optimization and evolutionary multi-objective optimization algorithms that the Hypervolume (HV) is one of the most commonly used set quality indexes31. HV measures the volume of a region in the target space contained in a set of non-dominated solutions obtained by reference points. A larger HV value indicates better overall performance of the solution set. It can be used to compare the quality of the solution sets in the pareto front produced by the algorithms, and cannot be used to estimate the quality of a single optimal solution in a multi-objective optimization problem.

Proposed AMOMCKD-CNN model

A CBFD method based on AMOMCKD-CNN is proposed to solve the problems of various fault separation and complex feature extraction in traditional intelligent CBFD methods.

AMOMCKD-CNN

Combining bi-objective optimized MCKD with Improved CNN, a method called AMOMCKD-CNN is constructed, with the overall process shown in Fig. 2. First, the original vibration acceleration signal is obtained from the rolling bearing through continuous sampling. Then, the kurtosis and envelope entropy are designed as a bi-objective fitness function of NSGA-II, and the multi-objective evaluation index HA is innovatively designed to complete the optimization adaptively search for the key parameters L and T of the MCKD. Following that, the signal is filtered using the optimized MCKD to enhance the correlation characteristics of different failure modes. Subsequently, the filtered signal, with its periodic impulse characteristics, is segmented and input into the CNN, where an appropriate kernel size is set for feature extraction and classification. Finally, visualize the sensitivity of the kernel size to fault pulses to estimate the impact of varying the kernel size. The proposed AMOMCKD-CNN can be used to better extract and utilize the characteristics of the failure modes, providing an effective method for CBFD.

Proposed AMOMCKD method

The choice of the fitness function is essential for the proposed AMOMCKD method. The kurtosis K has been identified as an important index for fault signal detection32. It is the fourth central moment of the original vibration acceleration signal \(x_n\), as shown in Eq. (9).

Here, \(~\overset{-}{x}\) denotes the mean amplitude of \(x_n\).

Higher kurtosis values indicate more severe bearing faults. However, its use may place too much emphasis on signal skewness and may ignore periodic components. Envelope entropy is introduced as a quadratic measure to balance the effects of transient pulses and periodic components. Envelope entropy \(E_{p}\) reflects the sparsity, as shown in Eq. (10).

Here, \(w_n\) represents the signal obtained after Hilbert demodulation of signal \(x_n\).

When the filtered signal contains more noise and fault features are not obvious, the sparseness of the signal is weak, which leads to high envelope entropy. Conversely, envelope entropy is lower when the filtered signal has clearer fault features and is sparser33. If the filtered signal exhibits lower envelope entropy and higher kurtosis, the periodic pulse features in the signal are more significant, which is more conducive to the extraction of fault features. Therefore, the selection of kurtosis and envelope entropy as a bi-objective fitness function for NSGA-II can better optimize the key parameters of MCKD and better reflect the dynamic behavior of the signal, including both periodic and non-periodic components, so that the information in the entire fault signal can be used more fully.

To solve the problem of selecting a single solution from the set of non-dominated solutions and overcoming the shortcomings of HV, this paper proposes a new index called HA for selecting individual solutions in non-dominated solution set. The process of calculating HA is shown in Fig. 3. Firstly, the reciprocal of kurtosis is taken as the horizontal axis and envelope entropy as the vertical axis. Theoretically, to minimize both objectives, the reference point is set at (0,0). Secondly, in this example, \(x_4\) represents the maximum reciprocal value of kurtosis, and \(y_1\) represents the maximum value of envelope entropy, as a datum point (\(x_4\), \(y_1\)). Subsequently, the ratio of non-dominated solutions is calculated and projected onto the axis of 1\(\times \)1 coordinates to assign bi-objective equal weight. Finally, the area between projection points and reference point (0,0) is computed as the final performance evaluation of the algorithm.

The paper integrates HA into NSGA-II for adaptive optimization of key parameters (L, T) in MCKD, as shown in Algorithm 1. Lines 1-11 of Algorithm 1 demonstrate the process of selecting the non-dominated solution set, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Initial population of size \(n=30\), made up of random sets of two typical design parameters, will be used as the starting point in NSGA-II. The algorithm will operate with a crossover probability \(pc=0.9\) and a mutation probability \(pm=0.1\). Additionally, the max evolution iteration \(t_{\text {max}}\) is set to 20 to search for the best parameter combination for two typical designs. In lines 12-19, the HA values of each individual in the non-dominated set are calculated for the final selection. HA maps HV to a single solution in a non-dominated set and compares individual solutions. The HA value indicates the balance between the two objectives. Thus, the L and T with the highest HA values are selected as the final filtering parameters for MCKD.

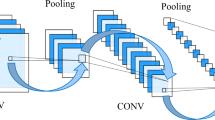

CNN Architecture

In CNN, the size of the convolution kernel determines its receiving field and directly affects CNN performance. To better capture the horizontal features of the input one-dimensional signal, the kernel height was set to 1. The kernel only computes the input signal horizontally, not vertically, to conform to the physical characteristics of the signal. Given that fault impulses typically exhibit rapid growth followed by decay, different threshold factors, denoted as \(\gamma \), are set to determine the pulse widths for different fault types. When a fault signal initially exceeds the threshold, it must subsequently drop below the threshold to be detected again. The threshold selection thus determines the widths of the signal pulses extracted from different scales.

The process of determining the kernel width for CNN involves five main steps, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Initially, the original vibration acceleration signal is collected to capture the acceleration response of a fault sample (Fig. 4a). Next, the acceleration envelope signal is extracted, illustrating an example of the inner ring fault envelope, retaining only the positive half (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, to minimize noise interference, the fault pulse width is analyzed by evaluating the difference between the mid-threshold \(A_{mid}\) and the transition point \(t_{\gamma }(k)\) of the envelope signal’s rising and falling edges. This analysis is performed under different \(\gamma \) values (Fig. 4c), as defined in Eq. (11). Subsequently, a series of fault pulse widths is determined using Eq. (12-13) (Fig. 4d), along with a corresponding local magnification of the envelope signal (Fig. 4e). Finally, to ensure complete coverage of all critical pulse features within the envelope signal, the largest pulse width is selected as the final kernel width (Fig. 4f).

Here, \(A_0\) denotes the maximum amplitude of the envelope signal, \(t_{mid(k)}\) represents the sampling time corresponding to the k-th intersection of \(A_{mid}\) and the envelope signal, and \(W(\gamma )\) refers to the kernel size determined by the proposed method.

Through the analysis of the relationship between acceleration signal features, a CNN model highly correlated with signal features was established. The proposed CNN structure consisted of two convolutional layers, two pooling layers, one fully connected layer, and one Softmax layer. Table 1 provides detailed parameters of the CNN model architecture.

Experiment

Dataset description

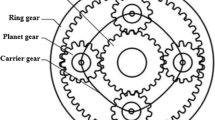

The experiment utilized the public bearing data set of Paderborn University (PU) dataset in Germany, as depicted in Fig. 5.

The experimental setup comprised a test motor, a measurement shaft, a bearing module, a flywheel, and a load motor, with the data set covering both artificially induced and real damage scenarios. The vibration acceleration signal was collected using piezoelectric accelerometers at a sampling frequency of 64 kHz. Bearing damage conditions were categorized into five levels, with levels 1 to 5 indicating increasing severity of damage. The data in this paper encompassed vibration data from eight different states under conditions of 900 rpm speed, 700 Nm torque, and 1000 N radial force. Time-domain vibration acceleration signals from eight samples were selected for experimental analysis. Details of the samples and tag number are presented in Table 2.

Selection rules for L,T

Before using MCKD optimization, it is necessary to determine the search range of L, T. Experimentally, the search range of L is set as [2,700]34. For T, it can be theoretically calculated by the fault characteristic frequency. The specific fault types are outer ring faults, inner ring faults, and ball faults, and the corresponding fault characteristic frequencies are \(f_{BPFO}\), \(f_{BPFI}\) and \(f_{BSF}\), as shown in Eq. (14-16):

where z denotes the number of rolling balls, \(f_{r}\)stands for the shaft frequency, d, D, and \(\beta \) designates the ball diameter, pitch diameter, and bearing initial contact angle, respectively. From Eq. (4), the search range of T is as shown in Eq. (17):

For the bearing data set from Paderborn University, this paper uses data with fault types consisting solely of either inner or outer ring faults. The search range for values of T is calculated from Eq. (17) to be [800,1400], without considering ball faults. Table 1 displays the experimental data for evaluating the AMOMCKD model’s performance. The NSGA-II algorithm optimized the key parameters of MCKD, which were subsequently used in the deconvolution processing of the fault vibration acceleration signal to produce a filtered signal with enhanced periodic impulse characteristics. Table 3 lists the optimal allocation combinations of L and T corresponding to different types of fault samples.

AMOMCKD deconvolution analysis

Figure 6 illustrates comparisons between filtered signal and original signal under different fault conditions using NSGA-II and PSO algorithms. To ensure fair comparisons, the fitness function of the algorithms were consistently set. The results show that the original signal demonstrates periodicity in the time domain but are greatly influenced by noise interference, leading to unclear fault impulses. After AMOMCKD filtering, the method successfully extracts the desired periodic transient pulse components, while effectively decoupling compound faults. PSO-MCKD filtering can extract pulse features of the original signal in some cases (KI18, KA22), but unexpected deformations occur in signal KB27 and KB24, such as inaccurate frequency characteristics, waveform distortion, or amplitude response offset.

Additionally, the comparison of bi-objective optimization results in Fig. 7 reveals that the unexpected deformations in KB27 and KB24 are caused by excessively large kurtosis indices. The situation indicates weak convergence assurance of PSO-MCKD in bi-objective optimization, which makes it difficult to effectively escape local optima. Moreover, in terms of envelope entropy, it is evident that the proposed method achieves the minimal indices. Therefore, AMOMCKD demonstrates an improved balance between kurtosis and envelope entropy indices, especially in compound fault signal.

To further validate the effectiveness of AMOMCKD in extracting acceleration signal features, this paper analyzed by visualizing the envelope spectra of deconvolved signal. As shown in Fig. 8, the envelope spectra of filtered signal from primary inner race fault KI21 and primary outer race fault KA22 reveal fault characteristic frequencies with apparent amplitudes and distinct frequency harmonics. In contrast, the envelope spectra of original signal from secondary inner race fault KI18 and secondary outer race fault KI16 exhibited irregular fault frequency characteristics in the low-frequency range due to interference, which was successfully overcome by AMOMCKD filtering. For the primary compound fault KB27, clear fault frequency harmonics were observed in the original signal envelope spectra. However, the coupling effects between inner and outer race faults impacted the secondary compound fault KB23 and tertiary compound fault KB24, resulting in significant distortion of fault frequency characteristics in their original signal envelope spectra. Utilizing the unique deconvolution capability of the AMOMCKD method significantly attenuated the influence of non-fault-induced frequency components, enhancing the identification of fault frequencies and laying a solid foundation for subsequent model feature extraction.

Experimental results and analysis

This section primarily focuses on the evaluation of the AMOMCKD-CNN model. The selected data will be randomly divided into training, validation, and test samples in a 4:1:1 ratio, with each fault type containing 400 samples and each sample having 2048 data points. The experiments are conducted on a computer running Windows 10, equipped with a multi-core 3.2 GHz Intel Corei9-12900K CPU, 64 GB of system memory (RAM), and two NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 graphics cards.

A batch size of 32 was set for all methods, Adam optimizer was chosen, and Cross Entropy served as the loss function. Throughout the training, the learning rate was set to 0.001, with 100 epochs. Based on K-fold cross-validation, each model underwent 10 experiments, and the average score of these 10 experiments was taken as the final score for comparative analysis. These experiments were implemented using the TensorFlow and Keras frameworks.

In terms of determining the kernel width, this paper investigated the effect of measuring the kernel width at different thresholds on diagnostic accuracy. Different \(\gamma \) values ranging from 0.1 to 0.9 were explored. These values represent different kernel widths for feature extraction across scales. Table 4 lists the fault pulse lengths extracted for different fault types with varying \(\gamma \) values. Afterward, outer race, inner race, and rolling element faults in the PU dataset were tested to compare the effects of different kernel widths on CNN classification accuracy (see Table 5), with a (3,3) square kernel used as a benchmark. Results showed a roughly 20% performance advantage of rectangular kernels over square kernels, further confirming that classical kernel sizes may not always be suitable in non-image processing domains. Figure 9 illustrates the kurtogram corresponding to each sample. The introduction of 2D kurtogram-based representations significantly improved classification performance compared to simple 2D reshaped data. The kurtogram representation yielded a mean accuracy of 85.621%, outperforming the 2D reshaped input by a notable margin. This demonstrates the kurtogram’s capability in preserving fault-related features across scales, making it a powerful tool for input preprocessing. However, the slightly lower classification accuracy of the kurtogram compared to 1D filtered data may be due to the insufficient signal length and the level being set to 4, which limits the information captured within the kurtogram.

Upon selecting the rectangular kernel, the kernel width needed to be determined based on the \(\gamma \) value. Performance improved as \(\gamma \) decreased from 0.9 to 0.5, with the optimal performance observed at \(\gamma \) = 0.5, yielding the highest median and mean accuracies, indicating more effective capture of fault pulse information within the receptive field by the CNN. However, as \(\gamma \) decreased from 0.5 to 0.1, CNN performance gradually declined due to an increase in non-fault pulse components within the receptive field, leading to decreased accuracy. As a result, the optimal \(\gamma \) value for the design of the first kernel width was determined to be 0.5, corresponding to kernel widths of 122 for the PU dataset.

After determining the kernel width in CNN, the AMOMCKD-CNN model was compared with CEEMDAN-CNN35, VMD-CNN9, and RAW-CNN. The impact of different data processing methods on the results was explored using the same data preprocessing approach. Figure 10 illustrates the comparison among the four models with different kernel widths. The designed kernel width in this study demonstrates notable advantages in various signal processing tasks, providing further evidence to guide CNN kernel design based on the pulse width of the vibration acceleration signal.

Specifically speaking, at a kernel width of 3, CEEMDAN-CNN and VMD-CNN demonstrate excellent feature recognition among fault classes, achieving accuracies of 96.25% and 95.31%, respectively. The performance surpasses that of the RAW-CNN, although it performs poorly in normal versus fault sample classification. Notably, AMOMCKD-CNN achieves 100% accuracy in normal versus fault sample classification and outperforms the other three methods overall, demonstrating its superiority in compound fault decoupling detection. At a kernel width of 122, all methods exhibit significant improvement. The single fault type recognition accuracies of CEEMDAN-CNN and VMD-CNN models on original vibration acceleration signal increase from 94.84% to 97.81% (an approximately 3% increase). However, these models exhibit unstable performance in handling compound faults, showing fluctuations. The AMOMCKD-CNN model effectively detects compound fault features by utilizing deconvolution algorithms to process original data before feeding it into the CNN. The model achieves recognition accuracies of approximately 99% for the KI18 inner race fault and KA16 outer race fault, with recognition accuracies exceeding 97% for compound faults KB27, KB24, and KB23, showcasing strong precision and generalization capabilities.

The t-SNE algorithm-based feature visualization results on the Paderborn test dataset, as depicted in Fig. 11, reveal the robust feature extraction capability of the AMOMCKD-CNN model. It effectively discriminates between samples representing different fault states, particularly distinguishing between normal and faulty signals. However, CEEMDAN-CNN and VMD-CNN exhibit some misclassifications in distinguishing different faults, especially in compound fault classification. The t-SNE feature visualization demonstrates the practical value of the proposed AMOMCKD-CNN model.

An important benefit of the adaptive selection kernel size model is its visualizability, which improves the interpretability of the model. The experiment investigated different operating conditions using the Paderborn dataset, utilizing intrinsic information from each channel in the model, where each channel corresponds to a specific feature extractor. The feature focused on observing the feature extraction of input pulse signal by adjusting the width of the first convolutional layer’s kernel. To facilitate visualization, the extracted feature information from each channel in the data sequence was combined and normalized, highlighting the significance of optimizing kernel widths for different types of fault pulses. Figure 12 illustrates the channel score visualization of normal bearing signal and seven different types of bearing fault signal from the Paderborn dataset, using both traditional and optimized kernel sizes, with brightness indicating the model’s focus on different signals. The results indicate that optimized kernel sizes better capture vibration impulse patterns in the signal. This method can simultaneously focus on different patterns and allocate more attention to significant patterns, thus possessing accurate fault diagnostic capabilities. These visualization results partially reveal the internal operational patterns of the model, aiding in a better understanding and interpretation of the model’s behavior and performance.

The method’s capability to handle signal of arbitrary lengths was validated in the visualization. Fault signals of different lengths (1024, 2048, 4096, 8192) were used as inputs for the model, and the visualization of scores for signals of different lengths is presented in Fig. 13. The results indicate that the method exhibits similar attention to identical vibration patterns across signal of different lengths, demonstrating the model’s strong generalization ability and robustness.

Further experiment

To further validate the performance of the AMOMCKD-CNN method, experiments were conducted using the publicly available dataset from Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), widely acknowledged as an authoritative benchmark for bearing fault diagnosis. Vibration acceleration signals from the drive-end bearings were used as the experimental dataset, encompassing faults in the rolling elements, inner race, and outer race. The experimental setup covered a load range of 0hp to 3hp and a speed range from 1730rpm to 1797rpm. Compound fault data was generated by directly summing corresponding single fault data to simulate different faults. All signals were measured using acceleration sensors at a frequency of 12kHz under various load torques and speeds. Table 6 presents the specifics of the samples and their tag number.

Compared to the Paderborn dataset, it is observed that the fault pulse components in the CWRU dataset are more distinct, and there is a significant difference between normal and fault signals, providing more favorable conditions for bearing fault diagnosis. Employing the same methodology as with the Paderborn dataset, Table 7 presents the extracted kernel widths with different thresholds, while Table 8 lists the corresponding CNN classification accuracies based on these kernel widths. The parameter \(\gamma \) for the CWRU dataset was determined to be 0.5, corresponding to a kernel width of 58.

Figure 14 illustrates the identification accuracy for each type of fault under different conditions, with kernel widths set to 3 and 58, respectively. For example, at a kernel width of 3, the model shows an average accuracy improvement of approximately 4% for compound fault tasks. Although it falls short in handling compound faults involving the inner race, outer race, and rolling elements, this method still secures the second position with a slight deviation from the top-performing approach. By adjusting the kernel size, significant improvements in average precision are observed across all methods. Figure 15 compares eight types of rolling bearing faults using t-SNE clustering analysis, demonstrating that convolutional kernel receptive fields can effectively perceive the regularity of fault pulses and capture these patterns. The AMOMCKD-CNN, through its unique deconvolution approach and optimally designed kernel sizes, efficiently and accurately extracts pulse features, showcasing excellent classification accuracy across all labels, particularly in handling compound faults. In summary, the AMOMCKD-CNN emerges as a versatile model that consistently delivers competitive performance across diverse datasets.

Experiments on both datasets demonstrate that the optimal gamma value is 0.5. Therefore, this study will modify the rotational speed in the Paderborn dataset from 900 to 1500 rpm, while keeping other conditions constant, for further analysis. Figure 16 shows its classification performance. When \(\gamma \) is reduced from 0.9 to 0.1, the changes observed in the data at 1500 rpm, which exhibit more pronounced periodic pulses, are similar to those at 900 rpm. The kernel width at 1500 rpm is generally smaller than at 900 rpm, as the signal pulses are more frequent and concentrated. In terms of classification performance, \(\gamma \) = 0.4 produced the best results, which corresponded to the 1500 rpm data pulse characteristics, which demonstrated the match between the CNN kernel width and the data pulse width.

Discussion and conclusion

A CBFD method called AMOMCKD-CNN based on adaptively optimized parameters MCKD and CNN is proposed. The main contributions of this paper are the development of a multi-objective optimization model to optimize key parameters of MCKD and the proposal of a novel HA metric for a more comprehensive evaluation of filtered signal quality. Additionally, the CNN feature extraction structure is optimized to enhance interpretability. A significant aspect of AMOMCKD is its capability to eliminate the reliance of MCKD on a single kurtosis index and reduce resonance phenomena caused by multiple faults simultaneously, resulting in the filtered signal with clear periodic pulses. Moreover, by incorporating the regular impulse characteristics of the filtered signal, the size of the convolutional kernel receptive field in the CNN is optimized. This optimization enables the visualization of the model’s attention to the signal in different states through the multi-feature channel information in the network’s first layer. Ultimately, leveraging the advantages of CNN feature learning, complex conditions of rolling bearing fault diagnosis are achieved. Analysis and validation using both the PU dataset and the publicly available CWRU dataset demonstrate classification accuracies exceeding 97%. Comparative evaluations with other optimization methods validate the robustness of the AMOMCKD-CNN approach. Compared to other state-of-the-art methods, the approach not only achieves satisfactory classification accuracy but also demonstrates strong stability, facilitating improved CBFD implementation.

Data availability

The experimental data used in this paper is from the rolling bearing database center of Case Western Reserve University(CWRU) in the United States (https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter/download-data-file) and the bearing dataset of the University of Paderborn, Germany (https://mb.uni-paderborn.de/kat/forschung/kat-datacenter/bearing-datacenter/data-sets-and-download).

References

Ma, P., Zhang, H. & Wang, C. Adaptive dynamic mode decomposition and its application in rolling bearing compound fault diagnosis. Structural Health Monitoring 22(1), 398–416 (2023).

Tang, G., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Liu, N. & He, J. Compound bearing fault detection under varying speed conditions with virtual multichannel signals in angle domain. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 69(8), 5535–5545 (2020).

Yu, D., Wang, M. & Cheng, X. A method for the compound fault diagnosis of gearboxes based on morphological component analysis. Measurement 91, 519–531 (2016).

Pu, H., Zhang, K., & An, Y. Restricted sparse networks for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics (2023)

Sun, Y. & Yu, J. Fault detection of rolling bearing using sparse representation-based adjacent signal difference. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 70, 1–16 (2020).

Du, J., Li, X., Gao, Y. & Gao, L. Integrated gradient-based continuous wavelet transform for bearing fault diagnosis. Sensors 22(22), 8760 (2022).

Ding, J. A double impulsiveness measurement indices-bilaterally driven empirical wavelet transform and its application to wheelset-bearing-system compound fault detection. Measurement 175, 109135 (2021).

Sun, Y., Li, S. & Wang, X. Bearing fault diagnosis based on emd and improved chebyshev distance in sdp image. Measurement 176, 109100 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Composite fault diagnosis for rolling bearing based on parameter-optimized vmd. Measurement 201, 111637 (2022).

Zhang, H., Shi, P., Han, D. & Jia, L. Research on rolling bearing fault diagnosis method based on amvmd and convolutional neural networks. Measurement 217, 113028 (2023).

Li, Y., Zhou, J., Li, H., Meng, G. & Bian, J. A fast and adaptive empirical mode decomposition method and its application in rolling bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Sensors Journal 23(1), 567–576 (2022).

Jiang, X. et al. A new l0-norm embedded med method for roller element bearing fault diagnosis at early stage of damage. Measurement 127, 414–424 (2018).

Cai, B., & Tang, G. Maximum spectral sparse entropy blind deconvolution for bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Sensors Journal (2024)

Miao, Y., Zhang, B., Zhao, M. & Lin, J. Period-oriented multi-hierarchy deconvolution and its application for bearing fault diagnosis. ISA transactions 114, 455–469 (2021).

McDonald, G. L., Zhao, Q. & Zuo, M. J. Maximum correlated kurtosis deconvolution and application on gear tooth chip fault detection. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 33, 237–255 (2012).

Li, K., Wu, H., & Han, Y. High-low frequency features fusion and integrated classification scns for intelligent fault diagnosis of rolling bearing. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics, 1–38 (2024)

Jun, Z., et al: Diagnosis of multiple faults in rolling bearings based on adaptive maximum correlated kurtosis deconvolution. J. Vib., Shock 38(22), 171–177 (2019)

Cui, H., Guan, Y. & Chen, H. Rolling element fault diagnosis based on vmd and sensitivity mckd. IEEE Access 9, 120297–120308 (2021).

Gao, S., Gao, Y., Zhang, Y. & Li, T. Adaptive cuckoo algorithm with multiple search strategies. Applied Soft Computing 106, 107181 (2021).

Kalyanmoy, D. A fast and elitist multi-objective genetic algorithm: Nsga-ii. IEEE Trans. on Evolutionary Computation 6(2), 182–197 (2002).

Wang, H., Liu, Z., Peng, D. & Cheng, Z. Attention-guided joint learning cnn with noise robustness for bearing fault diagnosis and vibration signal denoising. ISA transactions 128, 470–484 (2022).

Jin, Z., Chen, D., He, D., Sun, Y. & Yin, X. Bearing fault diagnosis based on vmd and improved cnn. Journal of Failure Analysis and Prevention 23(1), 165–175 (2023).

Dong, K. & Lotfipoor, A. Intelligent bearing fault diagnosis based on feature fusion of one-dimensional dilated cnn and multi-domain signal processing. Sensors 23(12), 5607 (2023).

Udmale, S. S., Singh, S. K., Singh, R. & Sangaiah, A. K. Multi-fault bearing classification using sensors and convnet-based transfer learning approach. IEEE Sensors Journal 20(3), 1433–1444 (2019).

Udmale, S. S., Patil, S. S., Phalle, V. M. & Singh, S. K. A bearing vibration data analysis based on spectral kurtosis and convnet. Soft Computing 23(19), 9341–9359 (2019).

Pang, P., Tang, J., Luo, J., Chen, M., Yuan, H., & Jiang, L. An explainable and lightweight improved 1d cnn model for vibration signals of rotating machinery. IEEE Sensors Journal (2024)

Shafin, S.S. An explainable feature selection framework for web phishing detection with machine learning. Data Science and Management (2024)

Li, F., Wang, L., Wang, D., Wu, J. & Zhao, H. An adaptive multiscale fully convolutional network for bearing fault diagnosis under noisy environments. Measurement 216, 112993 (2023).

Najaran, M. H. T. An evolutionary ensemble convolutional neural network for fault diagnosis problem. Expert Systems with Applications 233, 120678 (2023).

Ruan, D., Wang, J., Yan, J. & Gühmann, C. Cnn parameter design based on fault signal analysis and its application in bearing fault diagnosis. Advanced Engineering Informatics 55, 101877 (2023).

Guerreiro, A. P., Fonseca, C. M. & Paquete, L. The hypervolume indicator: Computational problems and algorithms. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 54(6), 1–42 (2021).

Gao, S., Shi, S. & Zhang, Y. Rolling bearing compound fault diagnosis based on parameter optimization mckd and convolutional neural network. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 71, 1–8 (2022).

Tang, G. & Wang, X. Parameter optimized variational mode decomposition method with application to incipient fault diagnosis of rolling bearing. 49, 73–81 (2015).

Lyu, X., Hu, Z., Zhou, H. & Wang, Q. Application of improved mckd method based on qga in planetary gear compound fault diagnosis. Measurement 139, 236–248 (2019).

Shi, L., Liu, W., You, D. & Yang, S. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on ceemdan and cnn-svm. Applied Sciences 14(13), 5847 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding Supported by Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (Grant No. 2024-047). Reviewers are also appreciated for their critical comments.

Funding

Supported by Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (Grant No. 2024-047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, R., Bai, Y., Yang, K. et al. Research on rolling bearing compound fault diagnosis based on AMOMCKD and convolutional neural network. Sci Rep 15, 14337 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96106-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96106-3