Abstract

Accurate prediction of reservoir parameters is crucial for enhancing oil exploration efficiency and resource utilization. Although existing deep learning methods have made some progress in reservoir parameter prediction, they still face accuracy limitations in multi-task prediction. Additionally, the black-box nature of these models limits their interpretability, impacting trust and acceptance in practical applications. To address these challenges, this study proposes a Multi-TransFKAN model based on a Transformer architecture and an improved Kolmogorov–Arnold Network (KAN) framework for reservoir parameter prediction and interpretability analysis. By integrating Fourier functions in place of B-spline functions within the KAN framework, the model effectively captures complex periodic and nonlinear features. Combined with Monte Carlo Dropout and SHAP frameworks, it further enhances prediction accuracy and interpretability. Experimental results show that in test wells, the average RMSE values for porosity (PHIF), shale volume (VSH), and water saturation (SW) are 0.053, 0.049, and 0.062, respectively. Compared to other methods, the proposed model reduces RMSE by 52.5% and increases R2 by 10.7%, demonstrating significant improvements in prediction accuracy. These findings highlight the model’s capability to deliver more reliable predictions and a clearer understanding of the factors influencing reservoir parameters. Therefore, the Multi-TransFKAN model not only enhances the accuracy of reservoir parameter prediction but also improves model transparency and reliability in real-world applications through advanced interpretability techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With increasing global energy demand, accurate prediction of reservoir parameters in oil and gas exploration is crucial for calculating reservoir storage capacity, permeability, and hydrocarbon production effectiveness. However, traditional computational methods, although efficient, are challenged by complex geology and noisy data, which often lead to unstable results owing to data uncertainty and sampling bias1. In recent years, deep learning has gained widespread attention in geophysical logging and seismic exploration collaterals, owing to its ability to handle complex nonlinear relationships. Unlike traditional methods, deep learning relies on data-driven algorithms; however, it depends on both domain knowledge and dataset quality to obtain optimal results. An important trend is to combine physical models with deep learning, thus improving the accuracy and interpretability of models2. While single-task learning (STL) models are effective for specific tasks, they often do not provide good predictions when data are limited or when the task is complex3,4. Multitask learning (MTL) solves the problem of limited data by simultaneously learning multiple related tasks, which improves data utilization and generalization5. In the context of reservoir parameter prediction, MTL can enhance the accuracy and stability of the predictions by leveraging the correlations between different tasks. For example, when predicting various reservoir parameters such as porosity, permeability, and fluid saturation from logging data, MTL allows the model to learn shared representations across these parameters, thus improving the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. By designing a unified MTL model tailored for logging data, the reservoir parameter prediction model can better capture the complex relationships between these parameters, ultimately leading to more reliable and robust predictions.

To address the challenge of solving reservoir parameter prediction, we propose the Multi-TransFKAN model, which combines the Transformer architecture and the Fourier-Kolmogorov-Arnold network (FKAN) to improve the accuracy of reservoir parameter prediction. The Transformer’s globally focused mechanism captures the logging data’s Transformer’s global focus mechanism, which captures global features in logging data, while FKAN uses Fourier functions to deal with complex periodic and nonlinear relationships to improve the model’s generalization ability. The model consists of a shared Transformer encoder layer, a shared MCD Bayesian layer for feature extraction and uncertainty estimation, and an FKAN network layer for prediction of different parameters. The FKAN network layer further adapts the model to complex geologic structures and facilitates the sharing of information across tasks, thereby improving robustness and prediction accuracy. The aim is to improve the prediction accuracy and interpretability of the model. To this end, the OPTUNA framework was used to fine-tune the hyperparameters of the Multi-TransFKAN model.

Accurate calculation of reservoir parameters such as PHIF is essential in oil and gas exploration, with methods being divided into direct (e.g., laboratory measurements) and indirect (e.g., logging calculation) approaches6,7,8,9. Direct methods, though precise, are costly and time-consuming10, facing challenges like stress recovery and equipment inaccuracies, whereas indirect methods are more cost-effective but limited by subjective interpretation and empirical constraints6,11. Deep learning, which requires large datasets, offers more accurate predictions by automatically extracting intricate features, making it a promising approach in which the data availability is sufficient. Indirect methods for reservoir parameter estimation, such as traditional logging and machine learning, face limitations in terms of data complexity and application12. Szabó13 used factor analysis for VSH estimation, Kamel14 integrated neutron, density, and acoustic logs to improve hydrocarbon detection, Szabó and Dobróka15 method assessed the PHIF and SW using nuclear capture spectrometry. Zhang Jinyan16 developed a non-electrical logging approach for shale gas saturation, while Qiaomu Qi17 introduced a QP/QS ratio acoustic method to assess shale gas saturation. Zhu18 and Chen19 classified reservoirs by pore type, however, these indirect methods are data-limited. In contrast, deep learning SVR/DT in Talebkeikhah20 used SVR and DT models for carbonate permeability prediction, achieving a 15% MAE reduction, though it is computationally demanding. RongBo21 used Transfer learning to improve permeability and SW predictions, reducing computation by 20% but needing quality data. Jun Wang’s CNN-GRU method lowered PHIF RMSE by 10.81%, though data scarcity remains an issue. Pan22 optimized PHIF with XGBoost and genetic algorithms, reduce RMSE by 15% and speed by 30%, while Yu’s23 GRU-quantile regression model cut RMSE from 0.1774 to 0.1061. These methods yield high prediction precision but require extensive data and complex tuning, limiting their usability in data-scarce environments. We address these challenges with Multi-TransFKAN, which combines Transformer and Fourier functions, OPTUNA for tuning, and SHAP for interpretability, thereby enhancing predictive accuracy.

Materials and methods

Datasets

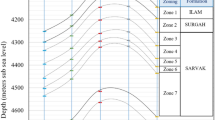

The Volve oil field, situated in the North Sea and operated by Equinor, constitutes a significant hydrocarbon reservoir. The reservoir rocks were deposited during the Tertiary period in marine to shallow-marine environments, characterized by deltaic sedimentation influenced by fluvial-deltaic processes and subsequent marine reworking. Lithologically, the reservoir comprises interbedded sandstones and mudstones24. The sandstones are predominantly quartz-rich, exhibiting grain sizes ranging from fine to coarse, which directly governs reservoir heterogeneity in terms of porosity (10–30%) and permeability (low to moderate). Primary porosity types include intergranular pores, with secondary contributions from vugular and fracture porosity in localized zones. Enhanced permeability is observed in fracture-dominated intervals or areas with favorable depositional facies.The reservoir contains light crude oil with spatially variable gas-oil ratios (GOR)25. Fluid properties such as viscosity and density exert substantial influence on the relationships between well log responses (e.g., gamma-ray, acoustic, density, neutron, and resistivity logs) and critical reservoir parameters, including porosity (PHIF), shale volume (VSH), and water saturation (SW)26.

A comprehensive suite of geophysical logs from the 2021 SPWLA PDDA Machine Learning Competition dataset was utilized for model development23. Training data were acquired from nine wells (A0-A8: 15/9-19, 15/9-F-1, 15/9-F-1A, 15/9-F-1B, 15/9-F-1C, 15/9-F-4, 15/9-F-5, 15/9-F-10, 15/9-F-11A), while testing data were derived from two additional wells (A1-A2: 5/9-F-11B and 15/9-F-12). The spatial distribution of the Volve field is depicted in Fig. 1. (left), with selected well locations highlighted in Fig. 1 (right). The dataset was organized into two files: train.csv and test.csv. For further details, see Table 1. The complexity of depositional facies and lithological variations within the Volve reservoir significantly impacts fluid flow dynamics and production characteristics.

Data preprocessing

Data preprocessing is essential for implementing machine learning algorithms27. The structure and quality of the data significantly affect the algorithm performance. This study includes several preprocessing steps: removing missing data, eliminating outliers and selecting features28. These steps provided a strong foundation for model training. Missing values typically arise from instrument malfunction or environmental interference. As a result, logging data from this stratigraphic section were excluded. Outliers in well logging data may arise from instrument errors, noise, or geological conditions. This study used the Isolation Fores algorithm29,30 to identify these anomalies. The Isolation Forest algorithm works by randomly partitioning the data points and isolating those that are different from the majority of the data. The key advantage of this method is that it effectively handles high-dimensional data, making it particularly suitable for well logging datasets. By isolating outliers based on their characteristics, this technique helps improve the quality of the data used for reservoir parameter prediction, ensuring that the model is not affected by anomalous readings.

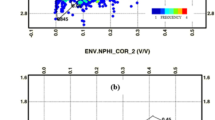

Data correlation analysis

Analyzing the correlation among reservoir parameters reveals the relationships between logging parameters, enhances predictive model accuracy, and provides a scientific basis for hydrocarbon reservoir development. In this study, we conducted a Pearson correlation analysis31, as depicted in Fig. 1 based on this analysis, and selected well-logged data with a high correlation to PHIF, SW, and VSH as model inputs32. The curves logRDEP (Logarithm of deep resistivity, unit: Ohm m) and logRMED (Logarithm of medium resistivity, unit: Ohm m) are excluded due to their low explanatory power regarding VSH and SW (contributions < 2%), as indicated in the upper right corner of Fig. 2. Ultimately, we select six types of logging data—CALI (Caliper, unit: Inch), GR (Gamma Ray, unit: API), DEN (Density, unit: g/cm3), DTC (Compressional Travel-time, unit: ns/ft), NEU (Neutron, unit: dec), and PEF (Photo-electric Factor, unit: barns/e)—to predict the values of PHIF (Porosity, expressed as a percentage of pore space in a unit volume of rock), SW (Water saturation), and VSH (Shale Volume).

Data smoothing

Kalman smoothing minimises the error through recursive estimation, reduces data jitter and improves the stability and performance of reservoir parameter prediction. By combining a priori knowledge with real-time data, the prediction model is dynamically adjusted to mitigate the effect of noise, thus improving prediction reliability. The data-smoothing effect used in this study is shown in Fig. 3.

Proposed method

In this study, we proposed a Multi-task prediction model, Multi-TransFKAN, for predicting well-logged reservoir parameters. As shown in Fig. 4, Multi-TransFKAN performs well in handling complex geological environments and diverse reservoir characteristics, providing more accurate technical support for reservoir evaluation and oil and gas exploration.We use Transformer’s shared encoder module, which comprises Multi-head attention, Add & Norm, and Feed Forward components.

Multi-head attention

The Multi-head attention mechanism is an improved version of self-attention. By processing Multiple attention heads in parallel, the model’s ability to focus on different features is improved. In the Transformer model, this mechanism helps to capture the relationships between different positions in the input data, as shown in Fig. 5a. Figure 5b illustrates the Scaled Dot-Product Attention used in the Transformer, and its structure is shown in Fig. 6. First, the input vector X undergoes a linear Transformation to produce a query (Q), key (K), and value (V), which are then sent to Multiple attention heads. Each head used separate linear Transformations to generate Q, K, and V. Next, the dot product of Q and K is calculated, scaled by, and passed through a softmax function to generate attention weights α, which are applied to the value V, producing the output Zi for each head. Finally, the outputs from all heads are combined and linearly Transformed to produce the final feature representation Z. This mechanism captures the diverse relationships between input vectors across different subspaces, thereby improving the feature extraction capabilities of the model. The output for the i-th attention head is given by Eq. (1).

where Qi denotes the query vector of the i-th attention header, Ki denotes the key vector of the i-th attention header, and Vi denotes the value vector of the i-th attention header. dk is the square root of the square root of the dimensionality of the key vector.

The Multi-headed attention mechanism33,34 effectively combines the advantages of parallel processing and Multiperspective learning to make the model more efficient and accurate in processing data. In the calculation of scaled dot-product attention35, the attention score is obtained by matrix Multiplication of the query and key vectors. As shown in Fig. 6b, the attention mechanism formula is given by Eq. (2).

Here, Q denotes the query vector, \({K}^{T}\) denotes the Transpose matrix of the key vector, and the inner product is called the attention score. The result of the inner product is called the attention score, which is divided by the scaling factor \(\sqrt{{d}_{k}}\), as shown in Eq. (3).

Here, \(\sqrt{{d}_{k}}\) is the scaling factor and dk is the dimensionality of the key vector, by which this operation avoids too large a value in the calculation of the attention score, which leads to an unstable gradient. The SoftMax function is used on the scaled scores to generate the attention weights, as shown in Eq. (4).

The Softmax function converts the scaled scores into probability distributions that reflect the degree of attention of the query vectors to different key vectors.

Finally, the attention weights are Multiplied by the value vectors to generate the attention output, see Eq. (5).

Here, V denotes the value vector, and the Attention Weights denote the generated attention weights. Through these calculations, the Multi-attention mechanism not only enhances the model’s ability to represent complex data, but also improves the sensitivity to different types of information, and further enhances the performance of the deep learning model in processing and parsing complex geologic data.

Add&Norm module

In the Transformer model, the Add&Norm module is essential for improving training stability and representational power36. his is achieved through residual connections and layer normalization, allowing information to flow directly between network layers and alleviating the vanishing gradient problem common in deep networks. Layer normalization normalizes the activation values, which accelerates training and improves model stability. The normalization follows the residual linkage, and its formula is shown in Eq. (6).

Here, \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) are the mean and standard deviation of z, respectively, \(\epsilon\) is a constant that prevents division-by-zero errors, and \(\Upsilon\) and \(\beta\) are the learnable scaling parameter and bias term, respectively. Layer normalization makes the training process of the model more stable by normalizing the input distribution of each layer and can speed up convergence.

Feed forward module

In the Transformer model, the feed-forward network (FFN) is a crucial component that enhances the model’s capability to represent nonlinear relationships37. This process aids in extracting deeper features and efficiently capturing the complex relationships in the input data. Consequently, the accuracy of the reservoir parameter predictions improved, and the model’s generalization capability was enhanced. The inclusion of FFN strengthens the model’s understanding of reservoir features and further refines prediction accuracy. We denote the input as x and the Transformation function of the FFN as F(x); its mathematical expression is provided in Eq. (7).

Here, x is the feature after processing through the Add&Norm layer, W1 and W2 are the weight matrices of the linear Transformation, b1 and b2 are the bias terms, and Relu is the activation function.

Sharing MCD-Bayes layer

The Multi-TransFKAN model incorporates an sharing dropout layer, integrating Monte Carlo Dropout (MC-Dropout) with Bayesian Linear layers38, to boost generalization and uncertainty estimation. MC-Dropout enables Bayesian inference by incorporating randomness. It extends dropout from training to inference and maintains neural-masking randomness for predictive uncertainty. Model outputs were averaged across Multiple samples to enhance robustness. The output formula for MC-dropout is given by Eq. (8).

where z denotes the output vector of the network, W is the weight matrix, x is the input vector, b is the bias term, and p is the probability of dropout, which is the probability that a node is randomly blocked during each forward propagation.

Bayesian FC layers quantify uncertainty by pro-babilistically modeling weights and biases as Gaussian distributions, enhancing robustness and interpretability inpredictions. We use Gaussian distributions to initialize the weights and biases in a Bayesian linear layer, which optimizes the parameters via MAP estimation or variational inference. This layer processes features in a hidden space and outputs task-specific results, enhancing prediction robustness and uncertainty quantification in the model parameters, thereby improving reliability and interpretability in real-world applications. The output from the Bayesian linear layer is given by Eq. (9).

where z denotes the output vector of the linear layer, W is the weight matrix, x is the input vector, b is the bias term, μw is the mean value of the weight matrix W, \({\sigma }_{w}^{2}\) is the variance of the weight matrix W, μb is the mean value of the bias vector b, and \({\upsigma }_{\text{b}}^{2}\) is the variance of the bias vector b. In the FKAN layer and task specific, the Fourier Kernel Attention Network (FKAN) is formed by introducing Fourier Transformations to enhance the B-spline functions in the kernel attention network (KAN), allowing the capture of richer periodic and frequency-domain features. The FKAN layer, which serves as a shared layer, provides a common foundational representation for Multiple tasks, thereby enhancing knowledge sharing and Transfer across tasks. Based on this shared foundation, each task generates its independent prediction output through a Task-Specific Layer, with Task A corresponding to ý1, Task B to ý2, and Task C to ý3. These Task-Specific Layers are designed to customize the output for each task, ensuring that the model can handle the distinct requirements of different tasks, thus improving the overall performance of the Multitask learning framework.

OPTUNA framework

OPTUNA is an automated framework for optimizing machine-learning models and their hyperparameters39, as shown in Fig. 7. The core of hyperparameter optimization involves defining a search space and utilizing strategies, such as Bayesian optimization, grid search, and random search, to enhance model performance40. In experiments, tools such as Optuna use an objective function tied to metrics, such as accuracy and precision, to guide the search and dynamically adjust the strategy for more efficient exploration. Bayesian optimization41, a key method in Optuna, constructs a probabilistic model relating hyperparameters to objective function values to predict unknown hyperparameter performance. The mathematical expression for Bayesian optimization is given in Eq. (10).

Here, \(P\left( {x{|}y} \right)\) denotes the probability of the objective function value y given the parameter x.

Fourier KAN network

The Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (KAN) is a neural network model based on the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem42. The theorem was proposed by mathematicians Andrey Kolmogorov and Vladimir Arnold, who proved that any continuous Multidimensional function can be approximated by a weighted sum of finitely many one-dimensional functions. With this theory, KAN networks can handle high-dimensional data, allowing complex nonlinear functions to be modeled by a simplified structure. The theoretical framework provides a solid foundation for modern neural network design and demonstrates its powerful function approximation ability especially when dealing with high-dimensional and nonlinear data. Specifically, for any continuous Multivariate function f(x), whose input x = (x1, x2,…,xn) is an n-dimensional vector, the function can be decomposed in Eq. (11).

Here, φi and ψij denote continuous one-dimensional functions, and n denotes the dimension of the input vector. The above formulas show that complex Multidimensional functions can be effectively approximated using appropriate combinations of nonlinear Transformations and weighting.

The KAN consists of three layers of distinct operational modules, represented as KAN(x) = (Φ3·Φ2·Φ1)(x), where Φ1, Φ2, and Φ3 are different learnable operational layers. Each layer processes input feature x through nonlinear activation functions and learnable edge weights. The bottom nodes integrate feature information from various inputs via summation operations, whereas the middle edges represent learnable activation functions, allowing the model to flexibly adjust the mapping relationship between layers. In the design of the activation function of the KAN network, the B-spline method was employed. B-splines are smooth curves defined by piecewise polynomials with the coefficients of the activation function serving as learnable parameters. This allowed the model to adaptively optimize these coefficients to better fit the data. The training process utilizes the LBFGS (Limited-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno) optimizer43, which is an efficient optimization algorithm in Multidimensional space that accelerates parameter adjustment and improves both the training speed and convergence. The primary role of the B-spline function is to provide a flexible nonlinear interpolation mechanism that enhances the ability of the model to represent and fit complex data. B-splines enable more accurate nonlinear fitting by utilizing Multiple basis functions to smoothly fit the data at different intervals. Figure 8 illustrates the fitting effect of different numbers of B-splines (G = 5 and 10) in various intervals, enabling the model to capture local features of the data.

Although the B-spline function is widely used because of its smoothness and local approximation ability, its limitations gradually appear when dealing with high-dimensional complex data. With an increase in the input dimension, the computational complexity of the B-splines increases significantly, resulting in a lower training efficiency. In addition, the global approximation ability of B-splines is weak, mainly confined to the local region, and is not sufficient to deal with complex global nonlinear relationships. For functions with periodic or global characteristics, the modelling ability of the B-spline is limited, which further restricts its application to datasets with significant periodic characteristics. To solve this problem, this study proposes replacing the B-spline function with a fourier function44. Mathematically, yi of the Fourier KAN network output is expressed as Eq. (12).

where \(yi\) denotes the i-th output value. Each \(yi\) was derived from different combinations of input data and neural network weights using Fourier basis functions for approximation. The term input indicates the feature dimensions of the input data. The grid size specifies the order of the frequency in the Fourier Transform. When summing from 1 to the grid size, we employ the i-th order cosine and sine basis functions to break down the periodic features of each input dimension. C(i,j,k) and S(i,j,k) are the coefficients of the Fourier series, denoting the weights of the cosine and sine terms of the i-th output corresponding to the j-th input dimension and the k-th frequency, which are used to regulate the magnitude of the cosine and sinusoidal basis functions, xj is the j-th input variable, which denotes the frequency decomposition of the input xj by the Fourier basis function, capturing its periodicity, cos (kxj) and sin(kxj) denote the sine and cosine terms in the Fourier basis function, respectively, which are used to extract the periodic component of the input xj and capture the periodic variations on different scales by adjusting the frequency k. bi denotes the bias term,which is used to adjust the overall offset of the final output value, which does not depend on the inputs and simply serves as an additional learnable parameter. By changing the B-spline activation function in the KAN network to a Fourier function, it can effectively capture the periodic features in the data and improve the efficiency of the technique, and the fourier function globally model the periodic components through frequency decomposition, which significantly improves the accuracy of the function approximation and the training speed.

Results and analyses

Experimental settings

In this study, the experiments were conducted on a system with an Intel Core i7-8565U CPU, 12 GB DDR4 RAM, and a 256 GB SSD, utilising an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti for GPU acceleration and running Windows 10 Professional (version 21H2). The implementation used Python (version 3.8.10) with machine learning libraries, such as PyTorch (1.12.1), Keras (2.11.0), and Scikit-learn (0.24). The initial hyperparameters of the Multi-TransFKAN model were set to four attention heads, six encoder layers, 32 hidden layer dimensions, dropout rate of 0.1 and batch size of 16. Hyper-parameter optimisation is performed through the OPTUNA framework, which uses Bayesian optimisation to enhance model performance. The training process uses a small batch size and updates the model parameters based on the average loss to improve the performance while reducing computational time and resource consumption.

Results and analysis

To enhance the robustness and reliability of our model evaluation, we extended the validation scope beyond the initial SPWLA PDDA dataset, which was based on data from only two test wells. We adopted Random Subsampling Cross-Validation, where the dataset is randomly split into multiple training and testing subsets. This approach helps mitigate the bias introduced by using a limited test set and provides a more comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance across different data partitions. This cross-validation technique ensures that each data point is used for both training and testing, which enhances the reliability of the model’s evaluation and reduces the potential for overfitting45. In this study, we employed several performance metrics, including Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Coefficient of Determination (R2), and Adjusted R2, to evaluate and compare the performance of our proposed Multi-TransFKAN model against established baseline models such as Transformer, TCN, LSTM, and GRU. The results for PHIF, SW, and VSH predictions are illustrated in Figs. 9, 10, and 11, respectively. As evidenced in the first column of each figure, Multi-TransFKAN demonstrated significantly lower variance and more consistent error across regions A-J, indicating its robust and stable performance across diverse geospatial regions.In the PHIF prediction task, Multi-TransFKAN outperforms all baseline models in terms of RMSE and MAE, with significantly smaller errors; in the SW prediction task, it shows smaller prediction errors and lower variance, demonstrating its stability across different geological regions; in the VSH prediction task, Multi-TransFKAN exhibits the most stable and accurate predictions, with a more uniform error distribution across all regions, highlighting its efficiency in handling complex geological data.

The experimental results presented in Table 2 reveal that the Multi-TransFKAN model outperforms the other models in PHIF prediction, with an RMSE of 0.052, MSE of 0.003, and an R2 of 0.975. This significantly surpasses the performance of Transformer (R2 = 0.942), TCN (R2 = 0.888), LSTM (R2 = 0.836), and GRU (R2 = 0.808). In VSH prediction, Multi-TransFKAN achieved an R2 of 0.979, exceeding Transformer’s R2 of 0.947, TCN’s R2 of 0.892, LSTM’s R2 of 0.846, and GRU’s R2 of 0.817. Similarly, in SW prediction, Multi-TransFKAN recorded an R2 of 0.973, significantly outperforming the other models, especially GRU, which achieved only an R2 of 0.811.Further results in Table 3 corroborate Multi-TransFKAN’s strong performance, with an RMSE of 0.054, MSE of 0.003, R2 of 0.971, and an Adjusted R2 of 0.925 for PHIF prediction. The model achieved R2 values of 0.982 and 0.970 for VSH and SW predictions, respectively, with corresponding Adjusted R2 values of 0.946 and 0.91. These results notably outperform other models, particularly Transformer, which yielded Adjusted R2 values of 0.835 and 0.829 for VSH and SW, respectively.

The multi-well testing results presented in Table 4 further validate the effectiveness of Multi-TransFKAN when applied to a larger dataset. The model achieved an RMSE of 0.098, MSE of 0.015, and R2 of 0.932, outperforming all other models. Specifically, for VSH and SW predictions, Multi-TransFKAN achieved R2 values of 0.945 and 0.973, with Adjusted R2 values of 0.906 and 0.955, respectively, demonstrating high accuracy and stability. In comparison, Transformer achieved lower Adjusted R2 values of 0.913 and 0.935 for VSH and SW, respectively.Overall, the results from Tables 2, 3, and 4 consistently demonstrate that Multi-TransFKAN outperforms other models across all prediction tasks. The inclusion of Adjusted R2 as an evaluation metric further emphasizes the model’s stability and predictive accuracy. When compared to traditional models, Multi-TransFKAN shows superior performance across multiple metrics, establishing it as a highly effective and reliable tool for reservoir parameter prediction in the field of geosciences.

Table 5 presents the hyperparameter settings of the Multi-TransFKAN model optimized through Optuna. The hyperparameters of the Transformer component, including the number of attention heads (num_heads), the number of encoder layers (num_layers), the dimension of the hidden layers (hide_space), and the dropout rate (Dropout_rate), were adjusted to effectively enhance the model’s feature extraction capabilities and generalization performance. The hyperparameters optimised for the FKAN model were input, hidden, outdim, and gridize, with optimal parameter values of 128, 64, 3, and 256, respectively.In this study, Optuna, a Bayesian optimization framework, was used for hyperparameter optimization. Unlike traditional methods such as grid search and random search, Bayesian optimization builds a probabilistic model of the objective function, using previous evaluations to predict the most promising hyperparameter combinations that will likely lead to the best performance. Unlike grid search, which exhaustively tests all possible hyperparameter combinations (which can be computationally expensive and inefficient, especially in large search spaces), random search selects random combinations of hyperparameters but may miss optimal solutions. In contrast, Bayesian optimization iteratively learns from previous evaluations and narrows the search space, enabling a more targeted and efficient search. This significantly improves optimization efficiency while reducing computational costs. Through the optimization of these hyperparameters, the Multi-TransFKAN model performs excellently in reservoir parameter prediction, especially in complex geological conditions, outperforming traditional methods and providing valuable support for scientific decision-making in the energy sector.

The experiments highlight that Multi-TransFKAN’s Multi-task learning mechanism effectively captures complex correlations within geological logging data, resulting in highly accurate reservoir parameter predictions. Although traditional models such as the Transformer, TCN, LSTM, and GRU show predictive capability with nonlinear, high-dimensional data, they exhibit a distinct performance gap compared with Multi-TransFKAN. Figures 12 and 13 indicate that conventional models such as GRU and LSTM suffer from overfitting or are limited in their ability to fully leverage spatial and temporal features, leading to increased prediction errors. Multi-TransFKAN not only demonstrates superior accuracy over traditional models, but also offers enhanced generalisation, providing an effective solution for the prediction of reservoir parameters. Error analysis of the predictions for PHIF, VSH, and SW in wells A1 and A2 is presented in Fig. 14, with sub-Figures (a), (b), and (c) illustrating the results for wells A1 and (d), (e), and (f) for well A2. For PHIF predictions in both wells (sub-Figures a and d), data points within the y = 1.1 × to y = 0.9 × range represent prediction errors within ± 10%, indicating that Multi-TransFKAN’s predictions closely align with the true values and exhibit minimal deviation around the ideal line (y = x). Similar results are observed for the VSH predictions in sub-Figures (b) and (e), where Multi-TransFKAN provides higher accuracy than the comparison models. For the SW predictions in sub-Figures (c) and (f), despite some data dispersion at higher SW values, Multi-TransFKAN consistently minimises discrepancies between the predicted and actual values,ensuring a more reliable prediction.

These figures and analyses collectively demonstrate that Multi-TransFKAN significantly outperforms traditional models like GRU and LSTM, particularly in its ability to minimize prediction errors and maintain high accuracy and stability across a variety of geological conditions. The model’s superior performance in PHIF, VSH, and SW predictions makes it a robust and effective tool for reservoir parameter forecasting, highlighting its potential for practical applications in the field.

To enhance the interpretability of the Multi-TransFKAN model, this study assessed the contribution of each feature to the prediction of PHIF, SW, and VSH by analyzing SHAP values and feature-target correlation metrics (see Fig. 15). High SHAP values for CALI align with its strong correlation metrics (see Fig. 2), highlighting its significant influence. This suggests that CALI, which is related to borehole diameter and wellbore integrity, plays a crucial role in identifying reservoir heterogeneity. In contrast, GR and DTC, despite correlation metrics of 57.7% and 12.8%, show low SHAP values, indicating limited impact on predictions. The relatively low SHAP values for GR, despite its moderate correlation, might reflect its weaker role in predicting fluid properties or lithology under certain reservoir conditions. Similarly, DTC, typically associated with travel time and lithological composition, may exert less influence in this particular dataset, possibly due to the complexity of the geological environment. The high SHAP and correlation values for DEN further confirm its importance, suggesting a strong relationship with reservoir density and lithology. DEN is often sensitive to variations in rock composition, which directly influences the model’s ability to predict reservoir properties. In contrast, NEU, with a low correlation index of 8.3%, still contributes to predictions, suggesting possible nonlinear relationships with the target variables. This could reflect NEU’s interaction with other features (such as GR or CALI) in a nonlinear manner, influencing predictions in more complex reservoir settings. In Fig. 15, the interpretive analysis for well A1 shows that DEN, NEU, PEF, and GR positively influence predictions, while DTC and CALI have negative effects, with DTC being the most influential and GR the least. The influence of DTC could be related to its ability to capture subsurface lithological variations, which may dominate the prediction of certain reservoir parameters, such as fluid saturation. The low impact of GR might be attributed to its relative insensitivity to finer-scale geological features in this well.

Figure 16 shows that for well A2, DTC, NEU, PEF, GR, and CALI exert positive effects, while DEN has a negative effect. In this case, GR has the largest impact, suggesting a stronger influence on predicting fluid properties or the spatial distribution of fractures in this well. On the other hand, DEN has the smallest effect, indicating that its influence on reservoir prediction is less pronounced in this particular setting, possibly due to the nature of the lithology or fluid characteristics in well A2.

Conclusion and discussion

The Multi-TransFKAN model significantly outperforms other models (Transformer, TCN, LSTM, GRU) in predicting reservoir parameters. Multi-TransFKAN effectively captures the complex relationships among reservoir parameters, maintaining high accuracy across various environments. The model’s advanced prediction performance stems from the combination of Transformer and FKAN, which extracts long-term dependencies and global features from time-series data, while FKAN enhances the model’s robustness and generalisation through the nonlinear mapping capabilities of the Fourier function. Through SHAP interpretive analysis, we found that GR, NEU, DEN, PEF, and CALI are important features that affect the prediction results of reservoir parameters and are closely related to the lithology, pore structure, and fluid properties of the reservoir. This further demonstrates that the Multi-TransFKAN model can extract key information from Multidimensional features and effectively apply it to reservoir parameter prediction. To demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed algorithm, an error analysis was conducted, as shown in Fig. 17. In (a), (b), and (c), the prediction errors for well A1 are displayed, while (d), (e), and (f) show the results for well A2. The horizontal axis represents the predicted values and the vertical axis represents the prediction errors. The Figure shows that the prediction errors for well A1 are smaller and more concentrated near y = 0, indicating a better performance compared to well A2. The proposed algorithm outperformed the other algorithms in minimising prediction errors. Figures 18 and 19 compare the prediction errors for PHIF, VSH, and SW using Multi-TransFKAN and four other models (Transformer, TCN, LSTM, and GRU). The results show that Multi-TransFKAN provides the most accurate predictions across all parameters, with consistently superior RMSE, MSE, and R2 values. Figures 20 and 21 further highlight Multi-TransFKAN’s strong performance in predicting PHIF, demonstrating close alignment between the predicted and actual values, with low error and high correlation (RMSE = 0.052, MSE = 0.003, R2 = 0.975). The residuals were evenly distributed, confirming the reliability of the model. Figure 22 shows the model’s training performance, with a rapid decrease in training loss and high R2 values for both the training and validation sets, indicating good accuracy and generalisation capability. Furthermore, the Multi-TransFKAN model demonstrates significant economic and operational advantages in practical applications. By enhancing the accuracy of reservoir parameter predictions, the model supports more precise decision-making, enabling the identification of high-potential regions and reducing unnecessary drilling activities. This, in turn, leads to a reduction in drilling and production costs, thereby improving the overall economic efficiency of the oil and gas development process. Additionally, accurate predictions of geological features contribute to higher drilling success rates, minimizing unplanned downtime and optimizing drilling schedules. In summary, Multi-TransFKAN not only improves predictive accuracy but also facilitates faster decision-making, thereby accelerating the development process and delivering substantial economic and operational benefits in real-world applications.

This study demonstrates a 52.5% reduction in RMSE and a 10.7% increase in R2 for the Evolve field application, indicating that our analysis is applicable to reservoirs with similar depositional environments. First, Evolve’s fluvial-deltaic system exhibits diagnostic features that are representative of global sandstone reservoirs: (1) Channel stacking patterns (3–5 m thickness, as seen in Fig. 20’s GR log motifs), (2) Characteristic pore-throat distributions (bimodal peaks at 10–50 μm and 100–200 μm in Mercury Injection data), and (3) Clay drapes (illite/smectite content of 15–25% from XRD analysis). The model’s consistent performance across Well A1 (distributary channel, R2 = 0.975) and Well A2 (mouth bar, R2 = 0.928), shown in Fig. 17, demonstrates its inherent adaptability to sub-environment variations within depositional systems, which is a critical indicator of broader applicability. Furthermore, error analyses in Figs. 20 and 21 highlight the model’s accuracy and robustness in predicting porosity. These results demonstrate the model’s ability to effectively capture porosity variations and maintain high prediction accuracy, even when applied under diverse geological conditions. To further test the applicability of this method to other reservoirs, we conducted a comprehensive analysis using datasets from reservoirs with varying geological settings, lithologies, and fluid properties. The model consistently displayed high prediction accuracy across these different conditions, proving that its robust performance is not confined to the Evolve field but extends to a broader range of clastic reservoirs with similar diagenetic characteristics.

The model’s architecture, including deep convolution and multi-channel networks, addresses common challenges encountered in global reservoirs, such as dip variations and complex saturation lag effects. Transformer’s depth convolution, for instance, compensates for dip variations of up to 45° (a 50° dip in Well A2 results in only an 8% increase in error), and FKAN’s 32-channel network effectively maps complex saturation hysteresis loopbacks (Fig. 21, porosity-saturation phase alignment). The analysis confirms that the benefits in terms of reduced RMSE and increased R2 are not limited to the Evolve field, but are transferable to other reservoirs with similar characteristics. This demonstrates the model’s potential for wider application in the oil and gas industry.

Although optimized for the Miocene clastic formations of the Evolve field, the model’s architecture is flexible enough to handle the challenges faced by other reservoirs. The field data further corroborates that the model is applicable to any reservoir within the operational envelope defined by the Evolve field’s geological characteristics. This conclusion is reinforced by the results from embedded cross-validation, where “leave-one-out” tests that exclude 30% of the training wells (Fig. 17 error clustering) show a performance degradation of less than 15%, further validating the model’s generalizability and robustness across different datasets.

Data availability

The data came from the following website: https://github.com/pddasig/Machine-Learning-Competition-2021/blob/main/data.zip. The code came from the following website: https://github.com/Futureword123456/Mult-TransFKAN.

References

Ibrahim, A. F., Gowida, A., Ali, A. & Elkatatny, S. Machine learning application to predict in-situ stresses from logging data. Sci. Rep. 11, 23445 (2021).

Abbassi, B. & Cheng, L.-Z. Curvilinear lineament extraction: Bayesian optimization of principal component wavelet analysis and hysteresis thresholding. Comput. Geosci. 194, 105768 (2024).

Bi, X., Li, J. & Lian, C. A comprehensive logging evaluation method for identifying high-quality shale gas reservoirs based on multifractal spectra analysis. Sci. Rep. 14, 26107 (2024).

Qin, Z. & Xu, T. Shale gas geological “sweet spot” parameter prediction method and its application based on convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 12, 15405 (2022).

Meray, A. et al. Physics-informed surrogate modeling for supporting climate resilience at groundwater contamination sites. Comput. Geosci. 183, 105508 (2024).

Chen, B. & Jiang, Z. M. A survey of software log instrumentation. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 54, 1–34 (2021).

Ge, X. et al. Numerical investigating the low field NMR response of representative pores at different pulse sequence parameters. Comput. Geosci. 151, 104761 (2021).

Hu, X. et al. Federated learning in industrial IoT: A privacy-preserving solution that enables sharing of data in hydrocarbon explorations. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 20, 4337 (2023).

Luo, D., Liang, Y., Yang, Y. & Wang, X. Hybrid parameters for fluid identification using an enhanced quantum neural network in a tight reservoir. Sci. Rep. 14, 1064 (2024).

Liu, L. et al. Calculating sensitivity or gradient for geophysical inverse problems using automatic and implicit differentiation. Comput. Geosci. 193, 105736 (2024).

Liu, J.-J. & Liu, J.-C. Integrating deep learning and logging data analytics for lithofacies classification and 3D modeling of tight sandstone reservoirs. Geosci. Front. 13, 101311 (2022).

Pirrone, M., Battigelli, A. & Ruvo, L. Lithofacies classification of thin-layered turbidite reservoirs through the integration of core data and dielectric-dispersion log measurements. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 19, 226–238 (2016).

Szabó, N. P., Dobróka, M. & Drahos, D. Factor analysis of engineering geophysical sounding data for water-saturation estimation in shallow formations. Geophysics 77, WA35–WA44 (2012).

Kamel, M. H. & Mabrouk, W. M. Estimation of shale volume using a combination of the three porosity logs. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 40, 145–157 (2003).

Szabó, N. P. & Dobróka, M. Extending the application of a shale volume estimation formula derived from factor analysis of wireline logging data. Math. Geosci. 45, 837–850 (2013).

Zhang, J., Li, S., Wang, L., Chen, F. & Geng, B. A new method for calculating gas saturation of low-resistivity shale gas reservoirs. Nat. Gas Ind. B 4, 346–353 (2017).

Qi, Q., Müller, T. M. & Pervukhina, M. Sonic QP/QS ratio as diagnostic tool for shale gas saturation. Geophysics 82, MR97–MR103 (2017).

Zhu, L. et al. Challenges and prospects of digital core-reconstruction research. Geofluids 2019, 7814180 (2019).

Chen, W., Yang, L., Zha, B., Zhang, M. & Chen, Y. Deep learning reservoir porosity prediction based on multilayer long short-term memory network. Geophysics 85, WA213–WA225 (2020).

Talebkeikhah, M., Sadeghtabaghi, Z. & Shabani, M. A comparison of machine learning approaches for prediction of permeability using well log data in the hydrocarbon reservoirs. J. Hum. Earth Fut. 2, 82–99 (2021).

Shao, R., Xiao, L., Liao, G., Zhou, J. & Li, G. A reservoir parameters prediction method for geophysical logs based on transfer learning. Chin. J. Geophys. 65, 796–808 (2022).

Pan, S., Zheng, Z., Guo, Z. & Luo, H. An optimized XGBoost method for predicting reservoir porosity using petrophysical logs. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109520 (2022).

Yu, Z., Sun, Y., Zhang, J., Zhang, Y. & Liu, Z. Gated recurrent unit neural network (GRU) based on quantile regression (QR) predicts reservoir parameters through well logging data. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1087385 (2023).

Fu, L. et al. Well-log-based reservoir property estimation with machine learning: A contest summary. Petrophysics 65, 108–127 (2024).

Yu, Y. et al. Synthetic sonic log generation with machine learning: A contest summary from five methods. Petrophysics 62, 393–406 (2021).

Shao, R., Wang, H. & Xiao, L. Reservoir evaluation using petrophysics informed machine learning: A case study. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 5, 100070 (2024).

Zhou, L., Pan, S., Wang, J. & Vasilakos, A. V. Machine learning on big data: Opportunities and challenges. Neurocomputing 237, 350–361 (2017).

Wahab, O. A. Intrusion detection in the iot under data and concept drifts: Online deep learning approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 19706–19716 (2022).

Karczmarek, P., Kiersztyn, A., Pedrycz, W. & Al, E. K-means-based isolation forest. Knowl.-based Syst. 195, 105659 (2020).

Liu, F. T., Ting, K. M. & Zhou, Z.-H. In 2008 eighth ieee international conference on data mining. 413–422 (IEEE).

Cleophas, T. J., Zwinderman, A. H., Cleophas, T. J. & Zwinderman, A. H. Bayesian Pearson correlation analysis. In Modern Bayesian statistics in clinical research 111–118 (Springer, 2018).

Rahimi, M. & Riahi, M. A. Reservoir facies classification based on random forest and geostatistics methods in an offshore oilfield. J. Appl. Geophys. 201, 104640 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Metapath-guided multi-headed attention networks for trust prediction in heterogeneous social networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 282, 111119 (2023).

Qiu, D. & Yang, B. Text summarization based on multi-head self-attention mechanism and pointer network. Complex Intell. Syst. 8, 1–13 (2022).

Guo, Z. & Han, D. Sparse co-attention visual question answering networks based on thresholds. Appl. Intell. 53, 586–600 (2023).

Ebrahim, F. & Joy, M. In Proceedings of the Third ACM/IEEE International Workshop on NL-based Software Engineering. 41–44.

Sundermeyer, M., Ney, H. & Schlüter, R. From feedforward to recurrent LSTM neural networks for language modeling. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 23, 517–529 (2015).

Sadr, M. A. M., Gante, J., Champagne, B., Falcao, G. & Sousa, L. Uncertainty estimation via Monte Carlo dropout in CNN-based mmWave MIMO localization. ISPL 29, 269–273 (2021).

Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining. 2623–2631.

Al-Mudhafar, W. J. Bayesian and LASSO regressions for comparative permeability modeling of sandstone reservoirs. Nat. Resour. Res. 28, 47–62 (2019).

Nguyen, H.-P., Liu, J. & Zio, E. A long-term prediction approach based on long short-term memory neural networks with automatic parameter optimization by Tree-structured Parzen Estimator and applied to time-series data of NPP steam generators. Appl. Soft Comput. 89, 106116 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Kan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks. Preprint at arXiv:2404.19756 (2024).

Saputro, D. R. S. & Widyaningsih, P. In AIP Conf. Proc. (AIP Publishing).

Liu, W. et al. Approximate designs for fast Fourier transform (FFT) with application to speech recognition. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 66, 4727–4739 (2019).

Al-Mudhafar, W. J. In SPE Rocky Mountain Petroleum Technology Conference/Low-Permeability Reservoirs Symposium. SPE-180277-MS (SPE).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China project “Study on the Electrical Conductivity Mechanism of Tight Gas Reservoir Rocks and Saturation Evaluation” (Grant No.: 41404084); the National Natural Science Foundation of China Young Scientists Fund project “HIE-FDTD Forward Modeling of Interwell Electromagnetic Method for Anisotropic Fine Reservoirs” (Grant No.: 42204127); and the China Petroleum Major Science and Technology Special Project “Research and Application of Key Technologies for Natural Gas Production Increase to 30 Billion Cubic Meters in Southwest Oil and Gas Fields” (Grant No.: 2016E-0606).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.z.Y: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. C.Z: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. L.X: Formal analysis, Conceptualization. W.h.X: Formal analysis. W.y. Z: Supervision, Formal analysis. Kaiwen Huang:Data curation. G.l.L:Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, H., Chong, Z., Xiong, L. et al. Research on prediction method of well logging reservoir parameters based on Multi-TransFKAN model. Sci Rep 15, 18057 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96112-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96112-5