Abstract

The heterogeneity structural characteristics of the pores in the coal matrix largely determine the storage and transport capacity of gas. In order to quantitatively characterize the pore structure in coal matrix and analyze the influencing factors, the filled pores (0.38–1.5 nm) and diffusion pores (1.5–100 nm) of seven coal samples with different metamorphic degrees were measured by low-temperature liquid nitrogen adsorption and carbon dioxide adsorption experiments, and combined with the theory of multifractality, the filled pores and adsorbed pores of coal samples with different degrees of metamorphism were characterized and discussed. The multiple fractal characteristics and influencing factors of the filled and adsorbed pores of coal samples with different metamorphic degrees were characterized and discussed. The results show that both diffusion pores and filled pores have multiple fractal characteristics; the more metamorphism, the more developed the filled pores and the stronger the heterogeneity. High-order coals had a strong heterogeneity of diffusion pores, while low-order coals exhibited a strong heterogeneity of filled pores. The heterogeneity of filled pores was negatively correlated with specific surface area and pore volume, while the opposite was true for diffusion pores. The relationship between pore heterogeneity and fixed carbon content showed a “U” distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The complex pore and fracture structure of coal1 influences the storage and migration of coalbed methane while facilitating gas storage and movement2. The ability of a coal body to absorb molecules of methane is impacted by its pore structure and the significant heterogeneity of the coal matrix. Notably, coal samples with varying coal quality levels show distinctly different pore structure features. Therefore, investigating the pore structure distribution of coal during different steps of coalbed methane (CBM) exploration and the differences in the heterogeneity of different coal samples is critical for optimum CBM exploration and gas disaster prevention.

As is well known, the pore structure of coal matrix is extremely complex and cannot be adequately described by traditional Euclidean geometry theories in terms of its complexity and irregularity3,4. Fractal theory, as a tool for characterizing complex phenomena, provides a novel scientific approach for investigating the intricate pore structures of coal5. Numerous scholars have conducted studies exploring the relationships between the complexity of pore structures in coal samples and their physical properties under varying external environmental conditions using fractal theory. Research has demonstrated a strong correlation between pore fractal dimensions and pore parameters, with micropores consistently exhibiting greater heterogeneity compared to mesopores6. Comprehensive fractal dimensions exhibit a decreasing trend with increasing pore volume and specific surface area7. On liquid nitrogen freezing, the pore structure of the coal body tends to smoothen and the pore fractal dimension shrinks, facilitating the movement and extraction of CBM8. The fractal dimensions D1 and D2 increase and decrease, respectively, with increasing number of liquid nitrogen cold soaks9. Increasing the coal deformation severity on tectonic coals results in relatively rough pore surfaces and uniform pore structures10. On the basis of the FHH model, the coal body fractal dimension decreases on impact loading, resulting in a linear adsorption capacity reduction11.

However, a single fractal dimension can only be characterized by one fractal parameter12, which merely describes irregularity within limited size intervals and fails to comprehensively characterize target features. In consideration of the aforementioned limitations, multifractal theory has been introduced to resolve the characterization challenges of complex pore structures in coal matrices. Multifractal analysis decomposes self-similar measures into interwoven fractal sets characterized by singularity strength, providing enhanced precision in pore structure characterization13. Recent applications of multifractal theory include pore structure investigations across diverse lithologies. Mulle14 digitized scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of sedimentary rock thin sections and conducted multifractal statistical analyses of their pore space geometries. Zheng et al.15 implemented multifractal formalism to evaluate pore size distribution heterogeneity in coals using low-temperature nitrogen adsorption calibration data. Zhang et al.16 investigated adsorption-influencing parameters through multifractal characterization of micropores and meso-macropores in medium-to-high rank coal samples. Xie et al.17 developed a digital analysis protocol integrating Environmental Scanning Electron Microscopy (ESEM) imaging with multifractal methodology to quantify carbonate pore networks. Wang et al.18 employed gas adsorption coupled with Field Emission-SEM (FE-SEM) and multifractal theory to differentiate pore structural features between coal and shale reservoirs.

Studies published to date mostly focus on the pore structure of systems with a pore size of > 2 nm, and limited methods are used to analyze and describe each pore structure19,20,21. Methane molecules exhibit distinct occurrence and migration patterns in pore structures of varying dimensions. Based on this characteristic and theoretical considerations, Cheng classified pores into four categories22: Inaccessible pores (< 0.38 nm), filled pores (0.38–1.50 nm), diffusion holes (1.50–100 nm) and seepage holes (> 100 nm). This classification framework establishes a theoretical foundation for subsequent multiscale investigations integrating microscopic mechanisms and macroscopic behaviors of methane storage and transport in coal matrices. A single pore testing method can only reflect the pore form of the coal body in a specific pore size section and cannot fully characterize the pore structure of the coal body at the microscopic nano level 23,24; a pore characterization method that combines multiple methods is more likely to accurately characterize all features of the multi-scale pore structure of coal. Building upon the aforementioned theoretical framework, this study investigates seven coal samples of varying ranks collected from distinct mining regions. Through comprehensive adsorption experiments integrating low-temperature liquid nitrogen (LN₂) and carbon dioxide (CO₂) adsorption techniques coupled with multifractal theory, we systematically characterized heterogeneity disparities in filled pores (0.38–1.50 nm) and diffusion-controlled pores (1.50–100 nm) across different coal ranks. Furthermore, the influences of pore structure parameters, fundamental coal properties, and vitrinite reflectance (R₀) on pore heterogeneity were quantitatively elucidated. These findings provide critical insights into gas storage mechanisms and migration dynamics within coal seams, establishing a theoretical foundation for optimizing CBM extraction efficiency.

Methods and experiments

Experimental samples

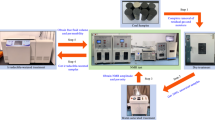

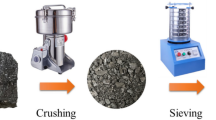

To study the differences in the heterogeneity pore structure of coal samples with varying levels of metamorphism, a total of seven coal samples from Shuanglong Coal(SL), Xiaozhuang Coal(XZ), Hujiahe Coal(HJH), Hongliulin Coal(HLL), Anju Coal(AJ), Chengzhuang Coal(CZ), and Zhaogu No. 2 Mine(ZG) in Ordos Basin were selected. The experimental samples were crushed and sieved, and 10 g of each sample with dimensions of 0.12–0.15 mm were weighed for industrial analysis and vitrinite reflectance determination (Table 1), and coal samples were categorized into low rank coal (R0 < 0.65%), middle rank coal (0.65% < R0 < 2.0%) and high rank coal (R0 > 2.0%) according to the criteria for determining the degree of deterioration of the coal by R025. Nos. 1 and 2 are low-rank coals, Nos. 3–5 are medium-rank coals and Nos. 6 and 7 are high-rank coals.

Gas suction

Samples (20 g) with sizes within 60–80 mesh were dried at 110 ℃ for 12 h, cooled, and evacuated at 200 ℃ for 5 h before being subjected to carbon dioxide and low-temperature liquid nitrogen adsorption experiments in an American Kantar AUTOSORB IQ automatic specific surface and porosity analyzer and ASAP2020 specific surface area and pore size distribution tester. Nitrogen adsorption experiments were conducted with liquid nitrogen (− 196 ℃) under a relative pressure range of 0.01–0.998 and carbon dioxide adsorption tests were conducted under a relative pressure range of 0.0001–0.0289; the features of pore size distribution were investigated by BJH and DFT pore size analysis.

Multiple fractal analysis

Based on the dichotomy method26, the relative pressure of gas adsorption is divided into units under different scales, ε. The mass probability distribution Pi(ε) of each unit cell at different scales can be expressed by Eq. (1). where Ni is the sum of gas adsorption and Ni(ε) is the gas adsorption within the ith unit27.

The mass probability distribution shows a scaling relationship with the scale. In the following equation, αi is the singularity index28.

Nα(ε), which satisfies the relationship with the scale ε, is the amount of subintervals labeled by α with a similar likelihood, and can be expressed as follows:

α(q) and f(α) can be obtained computationally as follows29,30:

where the order of the statistical matrix, denoted by q, is an integer within [− 10, 10], f(α) is the singular fractal dimension, and the bizarre fractal dimension spectrum is the curve comprising α and f(α).

Equation (7) represents x(q, ε), the definition of the distribution function31, where the quality index, denoted by τ(q), is the slope of lg x(q,ε) versus lg ε.

The generalized fractal dimension D(q) can be expressed as follows:

The volume dimension D0, data dimension D1, and association dimension D2 are represented by the values of Dq for q = 0, 1, and 2, respectively. The data dimension D1 indicates the degree of concentration of the pore size distribution; the volume dimension D0 involves the shrinkage properties of the number of not-unfilled boxes of different sizes; the association dimension D2 indicates the pore connectivity over different pore ranges; and H is the Hurst exponent, which varies from 0.5 to 1 32,33.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the joint pore structure of coal samples

Nitrogen adsorption and desorption curves

The low-temperature liquid nitrogen adsorption experimental results, as shown in Fig. 1, reveal that the nitrogen adsorption curves of all coal samples initially rise gradually and then increase rapidly with increasing relative pressure (P/P0). During desorption, the adsorption capacity decreases as the relative pressure declines. A sudden drop in the desorption curve occurs when the relative pressure approaches approximately 0.5, forming a hysteresis loop, which indicates the presence of ink-bottle pores in the coal samples. Different hysteresis loop types correspond to varying degrees of pore openness and pore geometries. Low-rank coal samples (Nos. 1 and 2) exhibit Type B hysteresis loops, suggesting that slit-shaped pores dominate their pore structures. Below a relative pressure of 0.5, the adsorption and desorption curves nearly overlap, implying that smaller pores are predominantly semi-open or semi-closed with limited openness. Medium-rank coal samples (Nos. 3–5) display Type B, Type A, and Type B hysteresis loops, respectively, reflecting cylindrical pores, parallel-plate pores, and slit-shaped pores. Similarly, their adsorption and desorption curves coincide below P/P0 = 0.5, signifying semi-open pores in smaller pores. High-rank coal samples (Nos. 6 and 7) show non-closing hysteresis loops, suggesting higher pore openness and adsorption-induced structural swelling during nitrogen adsorption. This non-closure phenomenon highlights enhanced pore accessibility and expansion effects in higher-rank coals.

Carbon dioxide adsorption isothermal curve

With increasing relative pressure (P/P0), the adsorption capacities of all seven coal samples exhibit a progressive rise. According to the IUPAC classification system for adsorption isotherms34, the CO2 adsorption curves in coal conform to Type I reflecting the adsorption characteristics of CO2 in pores smaller than 1.5 nm. Comparative analysis of adsorption isotherms across different coal ranks reveals that low- to medium-rank coals (Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) demonstrate significantly lower CO2 adsorption capacities than high-rank coals (Nos. 6 and 7) (Fig. 2). This disparity indicates a more developed network of pores with diameters below 1.5 nm in high-rank coals, which preferentially enhance CO2 adsorption through micropore-filling mechanisms. The observed trend aligns with the progressive pore structure refinement associated with coal maturation processes.

Joint pore analysis

Methane molecules in coal primarily exist in the adsorbed or dissociative state. Depending on the method of adsorption, methane adsorption on coal can be categorized as single-layer adsorption or microporous filling; microporous filling methane is associated with relatively high methane adsorption. Among the inaccessible pores, filled pores, diffusion pores and seepage pores proposed by Cheng, the pore structures in which methane molecules could not intervene with pore diameters less than 0.38 nm were inaccessible pores, and the pore structures of 0.38–1.50 nm, which served as the sites for adsorption of methane in the adsorbed state, were filled pores. Pore structures with pore size above 1.50 nm can be classified into diffusion pores (1.50–100 nm) and seepage pores (> 100 nm) by the difference in methane transport characteristics. Methane molecules exist in the adsorbed state in filled pores with a size of 0.38–1.50 nm as adsorbed microporous filling methane35,36. Methane molecules are subjected to a free force field superimposed on each other by neighboring pore walls; therefore, the adsorption force on microporous-filled methane molecules is significantly larger than that on methane molecules with a macroporous surface structure37,38. Methane molecules coexist as adsorbed and dissociative phases in relatively large pores (> 1.5 nm in size). The Langmuir formula can be used to characterize the monomolecular layer adsorption that occurs when methane molecules in the adsorbed phase adhere to the pore surface39. Methane is exposed to the liberated force domain of the pore border, and the pore-center methane molecules influence the pore border negligibly. Thus, under adsorption equilibrium conditions, the surface-adsorbed and dissociative-phase methane molecules remain in dynamic balance.

Combined with the effective aperture characterization domain of the adsorption experiments, the pore volume and specific surface area dispersion characteristics of the combined liquid nitrogen–carbon dioxide adsorption experiments of different coal specimens were analyzed by considering a joint pore boundary point of 1.5 nm. The pore size distribution features of combined pores in different coal samples are summarized in Table 2. Only a small percentage (not of reference significance) of percolating pores can be detected by low-temperature liquid nitrogen adsorption studies; consequently, only pore data within 0.38–100 nm were selected for subsequent analysis. The percentage of percolating pore volume and specific surface area are relatively small; the percentage of filled pore volume, specific surface area, diffusion pore volume, and specific surface area are 48.88–86.08%, 80.48–97.34%, 12.59–49.47%, and 2.65–19.49%, respectively. The different percentages of pore volume and specific surface in each size section indicate that the coal samples show a heterogeneity pore size and distribution. The pore volume and superficial area of filled, diffused, and seepage pores in coal increases with improving coal quality, and maxima in the volume of coal particles and specific surface space dispersion lines (Fig. 3) are observed in the filled pore section with pore sizes within 0.38–1.50 nm. Thus, the pore diameter dispersion of the filled pore section is concentrated in a specific region in which the number of pores is large, which is the main contributor of the coal pore volume and pore specific surface space; this system provides a relatively large space for methane molecule deposition and transportation. The peaks of high-order coals are significantly taller than those of middle- and low-order coals.

Multiple fractal fractions for carbon dioxide adsorption

Based on the double logarithmic curves of different scales, ε, and the collocation function x(q,ε) (Fig. 4), lg ε and lg x(q,ε) show a linear relationship that satisfies the scale invariance40. Therefore, the filled pores of each coal sample show the characteristics of multiple fractals when the statistical moment q > 0. Notably, a favorable relationship exists between lg x(q,ε) and lg ε, and an adverse relationship exists between lg ε and lg x(q,ε) when q < 0. The regression curves are similar, indicating that the pore diameter of the filled pores is mostly dispersed in the interval of smaller pores, which corresponds to the previously mentioned observation that the pore size of the filled pores is chiefly dispersed within 0.38–1 nm. Notably, the Nos. 6 and 7 coal samples contain a relatively high proportion of small pores than the other tested samples. Regression curves indicate that the Dq shows a monotonically declining tendency with increasing q (Fig. 5), consistent with the characteristics of multiple fractals; this confirms the accuracy of the previously mentioned partition function calculation. Table 3 shows that the D0 of filled pores of different specimens is 1, indicating that the pore size distribution interval of each coal sample is identical; as D0 > D1 > D2, the coal samples show significant heterogeneity, and the filled pores of the specimen D1 and D2 increase with increasing degree of coal quality. The degree to which the distribution of filled pore sizes is concentrated and homogeneity is reduced is indicated by D2, while D1 indicates the denseness of the pore volume dispersion of the pore diameter in different pore dimensions41. The filled pores in the No. 1 coal samples show the highest degree of aggregation with highest heterogeneity. D-10 − D10 indicates the grade of change of the pore size distribution in the local area; the spectrum width of middle- and high-order coals is larger than that of low-order coals, and the spectrum width of the left edge is smaller than the spectrum width of the right edge, which implies that the pore width dispersion of high-value areas significantly affects the influence of the local variability and heterogeneity of the filler pores. The dispersion of smaller pores in the range of filler pores is relatively homogeneous. The Hurst index (H) of the samples is distributed between 0.9451 and 0.9656; H represents the correlation between different pores42. Among all the tested samples, the H value of the No. 7 coal sample is the largest, possibly because the filled pores in the system comprise predominantly open pores that are relatively well connected.

The singular fractal dimension spectrum curves shown in Fig. 6 indicate an asymmetric convex parabolic distribution, and Δa reflects the inhomogeneity in the pore volume dispersion. A wider αq- − αq+ indicates a greater variability within the fractal and a relatively inhomogeneous distribution 43. The peculiarity coefficient α0 indicates the degree of concentration of the pore capacity dispersion. With improving coal rank, the α0, Δa, and degree of pore densification decrease, and the internal variability of pores reduces owing to a reduction in the localized distribution of pore volume volatility; moreover, the inhomogeneity and internal heterogeneity of the filled pores are weakened under coalification. The parameter Rd, numerically (α0 − α10) − (α-10 − α0), indicates the degree of deviation of f(α), which is centered on the symmetry line of α0 (Table 4). The plots of low-order coal-filled pores contain an evident right hook shape, indicating that the distribution of filled pore apertures is dominated by regions with relatively low probability (sparse regions).

Multiple fractal fractions of cryogenic liquid nitrogen adsorption

In successive intervals from q = − 10 to q = 10, the log–log graph of diffusion pores ε vs. x (q, ε) shows a linear relationship (Fig. 7), which satisfies the scale invariance, indicating that the diffusion pore with a caliber of 1.50–100 nm shows multiple fractal characteristics. When the q value increases from − 10 to 10, the gradient of the curve transitions from minus to plus and from sparse to dense. Notably, the curve of diffusion pores with a positive q is denser and larger than that of filled pores, and the pore caliber is mainly distributed in the interval of smaller pores, which corresponds to the concentration of diffusion pores near 50 nm in Fig. 3; higher-order coal contains a relatively high proportion of small pores. The generalized fractal spectrum curves of the diffuse pores show an inverse “S” shape (Fig. 8). Among all the tested samples, the coal samples Nos. 6 and 7 show higher and larger value domains than the filled pores, indicating that the diffuse pores show greater heterogeneity than the filled pores; moreover, higher-order coals show relatively high heterogeneity. The fractal dimensions (Table 5) follow the order D0 > D1 > D2; the D1 and D2 of high-order coal are significantly smaller than those of medium- and low-grade coal, and the diffusion pores are relatively aggregated and heterogeneity in high-order coal. The H of middle-order coal is greater than that of low-order coal, which is greater than that of high-order coal; additionally, the diffusion pores in high-order coal are poorly interconnected, and the connectivity of diffusion pores is generally lower than that of filled pores. The caliber dispersion variability in the high-value area of diffusion pores is higher than that in the low-numbers region; consequently, the high-numbers region mainly determines the pore size distribution variability.

The singular fractal dimension spectral curves of diffusion pores (Fig. 9) show a parabolic distribution; low- and high-order coal show a relatively large diffusion pore singularity index (Table 6). In these systems, the local variability of the pore volume is large; the internal variability of the diffusion pores first decreases and then increases with improving coal rank. The No. 4 coal samples shows the lowest heterogeneity of diffusion pores. Notably, the right-barb phenomenon is stronger for the diffusion pores than for the filled pores, and the low-probability density region contributes significantly toward the heterogeneity of the diffusion pore diameter distribution. The parameters of the odd fractal spectra of the diffusion pores of each specimen are significantly higher than those of the filled pores, and the heterogeneity of the diffusion pores is stronger than that of the filled pores.

Difference between multiple fractal characteristics of filled and diffusion pores

A comparison of the multiple fractal parameters of filled and diffusion pores (Fig. 10) indicates that the D1 and H of filled pores are larger than those of diffusion pores, and the D-10 − D10 and Δa values of filled pores are smaller than those of diffusion pores, implying that the filled pores show better connectivity and homogeneity than diffusion pores, which are poorly connected and show high heterogeneity. Notably, coal samples with high heterogeneity in filled pores do not show high heterogeneity in diffusion pores, i.e., the heterogeneity in filled and diffusion pores are not linearly related. Therefore, the heterogeneity of filled and diffusion pores should be analyzed separately. Moreover, D-10 − D10, Δa, and D1 show a strong negative correlation with H, implying that a coal body with high homogeneity shows relatively high pore connectivity.

Factors affecting the heterogeneity of the pore structure score

Influence of pore structure parameters on heterogeneity

The filled pore volume and specific surface area are typically labeled V1 and S1, respectively, while the diffusion pore capacity and specific surface area are labeled V2 and S2, respectively (Fig. 11). The filled pore D1 shows a direct association trend with the filled pore capacity and surface area44, and the filled pore D-10 − D10 and Δa show a negative correlation trend with the filled pore volume and specific surface area, possibly due to the high aggregation of pores with a size of 0.38–1.50 nm in low-order coals, the high variability and uneven distribution of the internal-diameter distribution of the pore, and the relatively strong heterogeneity in the system compared with that in middle-to-high-order coals. The filled pores show relatively small pore diameters and simple pore structures. In high-order coals, the count of filled pores increases, the pore surfaces are relatively smooth, and the heterogeneity is weakened; this enables the system to exhibit a large number of adsorptive positions45, thereby facilitating the adsorption of methane molecules.

The diffusion pore D1 increases and then decreases with increasing pore capacity and specific surface area and the D-10 − D10 and Δa decrease first and then increase with increasing diffusion pore volume and specific surface area; notably, the number of pores with pore diameters within 1.50–100 nm increases with increasing extent of coalification. In high-order coals, the extent of aggregation of diffusion pores and the distinction in pore distribution are relatively high, possibly because the pore framework of high-order coals tends to be complex and the exterior of the larger pores are rougher. In this system, the number of diffusion pores is large, the heterogeneity is high, the adsorption of methane molecules by the pore wall is relatively strong, and the force between pores is relatively large; these factors promote methane adsorption46. Analyses of the effect of the pore capacity and outermost pore regions on the heterogeneity of coal pores indicate that diffusion pores with a size of 1.50–100 nm are relatively isolated and non-uniformly scattered in the coal body, resulting in an intricate internal pore architecture within the coal mass.

Impact of basic parameters of coal samples on heterogeneity

Moisture in coal can be classified as intrinsic or extrinsic moisture; intrinsic moisture exists in the macromolecular structure of coal and is generally not easy to transform, while extrinsic moisture is mainly attached to the pore surface and occupies a part of the larger pore space. Extrinsic moisture affects the inhomogeneity of the coal body diffusion-pore apertures, smoothening them and reducing their heterogeneity47. Extrinsic moisture expansion enhances aggregation due to the pore effect (Fig. 12 a). The small pore diameter of filler pores makes the entry of moisture challenging; therefore, the effect of moisture on the heterogeneity of filled pores is not significant (Fig. 12 b).

In coal bodies with a size of 0.38–1.50 nm, the pore caliber dispersion variability declines with increasing ash content (Fig. 12 c), possibly because the ash in coal contains multiple non-organic minerals; during coal formation, these inorganic minerals are incorporated into the macromolecular framework of coal, obstructing some of its pores and reducing its outer rawness, affecting the heterogeneity nature of the pores in the system. Filler pores comprise a significant percentage of coal; therefore, the ash content of coal significantly influences the filler pores and the heterogeneity nature of coal (Fig. 12 d). The coal volatile fraction and ash are negatively correlated. Ash and the volatile fraction of coal mainly comprise inorganic and organic matter, respectively. In coal, when the content of organic substances is higher, the content of ash is relatively low48; therefore, coal samples with a high volatile fraction comprise an intricate pore framework (Fig. 12 e) and show a high degree of development and relatively strong heterogeneity (Fig. 12 f).

The coal body filled pore and diffusion pore D1 and the fixed carbon content show a “U-shaped” distribution. With increasing fixed carbon content, de-volatilization gradually loses its significance in the system and the small-pore count of the sample increases49. A higher percentage of filled pores leads to higher D1 values (Fig. 12 g); therefore, in high-order coals, the aggregation effect of filled pores is greater than that of diffusion pores. Consequently, the right half of the U-shaped curve contains filled-pore D1 data, while diffuse-pore D1 data are located in the descending stage of the curve (Fig. 12 h). With increasing proportion of micropores in the sample, the pore size variability first increases and then decreases.

Effect of the degree of coalification on heterogeneity

Liu50 found that the importance of macroscopic porosity decreases with increasing coal rank, while microscopic porosity becomes increasingly dominant, suggesting that the degree of coal metamorphism influences the degree of heterogeneity of coal porosity. Changes in the degree of coal metamorphism cause changes in the pore structure51. To elucidate the variability of the pore structure of coal under different degrees of metamorphism, the connection between the pore heterogeneity characteristics and the vitrinite reflectance of seven groups of coal samples were compared in this study. The filled-pore D1 is positively correlated with the degree of coalification. Under coalification, different coals show distinct features based on the pore development. As coalification improves, the degree of aromatization of the sample increases. As the aromatic-ring layer increases and is oriented, the diffusion pores tend to undergo rearrangement and are uniformly distributed under coalification52; moreover, the content of filled pores in the system increases. Thus, with coalification, the filled pore D1 and heterogeneity increases, while the variability of the pore size distribution reduces (Fig. 13). Compared with the coal samples with low vitrinite reflectivity, the Nos. 6 and 7 coal samples with high degree of metamorphism show relatively stronger filled pore heterogeneity.

Gray correlation analysis for determining the factors affecting the heterogeneity of coal body pores

Gray correlation analysis is a method that uses the level of growth trend resemblance or difference between factors as a proxy to determine the level of correlation between factors. In the gray correlation analysis, the original data matrix is constructed first. Elements that influence the heterogeneity of the coal body are used as the comparison sequence, and the heterogeneity parameter is used as the reference sequence to construct the original data matrix.

Let the reference sequence be as follows:

The comparison order is as follows:

where Xi(j) denotes the experimental result of the ith coal sample about the jth influence factor.

To avoid any influence of magnitude on the analysis results, the homogenization method was used to unify the magnitude as follows:

After harmonizing the quantities, the absolute difference matrix and the maximum (minimum) value were calculated as follows:

Finally, a gray correlation calculation was performed as follows:

In this case, γ0i is the gray correlation between the comparison and reference orders; a γ0i value closer to 1 indicates a higher correlation. Additionally, p is the resolution coefficient with a value of 0.

Numerous factors, including pore structural characteristics, basic parameters, and the degree of coal quality influence the heterogeneity of the coal body; the gray correlation analysis is carried out by combining the results of the above analyses with the heterogeneity of the filled and diffusion pores in the system. The gray correlations of the factors affecting the heterogeneity of the filled and diffusion pores are summarized in Table 7 and 8; the gray correlation values of the heterogeneity parameters of the filled pores, D1, D-10 − D10, and Δa, in descending order of the degree of significant influence are fixed carbon > volatile content > moisture > > pore specific surface area > pore volume > vitrinite reflectance > ash content. The gray correlation values of the heterogeneity parameters of the diffusion pores, D2, are in descending order of significant influence, and show the following order: volatile content > fixed carbon > moisture > vitrinite reflectance > ash content > specific surface area > volume. The gray correlation values of the influencing factors of the diffusion pore inhomogeneity parameters D-10 − D10 and Δa ranked in descending order of significant influence are as follows: fixed carbon > volatile content > moisture > vitrinite reflectance > specific surface area > ash content > volume. The gray correlation values of each influencing factor were averaged. From Table 9, it is evident that the pore-specific surface area of the pore structure parameters and the fixed carbon content of the basic parameters of the coal samples significantly influenced the pore heterogeneity. The heterogeneity of the filled pores is mainly affected by the basic parameters of the coal specimens and the pore structure parameters, and the heterogeneity of the diffusion pores was mainly influenced by the fundamental parameters of the coal specimens and the degree of coalification.

Conclusion

Differences in the heterogeneity characteristics of filled and diffusion pores with pore dimensions within 0.38–1.50 nm and 1.50–100 nm, respectively, in coal specimens with varying levels of metamorphosis were investigated in this study by combining the multiple fractal theory with low-temperature liquid nitrogen and carbon dioxide adsorption tests. Subsequently, factors influencing the heterogeneity of the pores were analyzed. The main results of this study can be summarized as follows:

(1) Low-temperature (temperatures below freezing nitrogen) and carbon dioxide adsorption experiments were used to characterize the pore structure of coal between various coal rank. Analyses showed that the pore structure and volume of coal of specific grades exhibit distinct heterogeneity and a double-peak characteristic (i.e., they decrease, increase, and then decrease again) with increasing pore diameter; in contrast, the pore specific surface area shows a single-peak characteristic (i.e., it increases and then decreases) with increasing pore diameter. Diffusion and filled pores with pore widths within 0.38–100 nm predominate the system. The average proportion of the specific surface area and filled pore volume, are 73.31% and 94.31%, respectively, and coal specimens with a greater extent of metamorphism show a more developed pore structure.

(2) Filled and diffusion pores of different coal specimens have multiple fractal features; the heterogeneity of diffusion pores is more intense than that of filled pores, and the pore diameters of filled and diffusion pores are primarily spread in the intervals of smaller pores. In low-grade coal (the No. 1 coal sample), the pore aggregation of filled pores is high, the difference of the pore internals is significant, and the heterogeneity is high. A noticeable variation is observed in the pore size distributions of the high- and low-value zones. Moreover, the diffusion pores of high- and low-order coal are heterogeneity. The heterogeneity of the coal pore correlates adversely with the connectivity, and high-order coal (the Nos. 6 and 7 coal samples) shows a high degree of diffusion pore aggregation.

(3) Numerous factors, including the pore geometry parameters, basic parameters of coal specimens, and degree of coalification, influence the heterogeneity of the pore space in varying coal rank. Increasing the pore volume and specific surface area decreases the heterogeneity of filled pores with a size of 0.38–1.50 nm and enhances the heterogeneity of diffusion pores with a size of 1.50–100 nm; moisture and ash fill some of the pores, resulting in weakened pore heterogeneity, and volatile matter shows a negative correlation with the content of ash in the system, which leads to enhanced pore heterogeneity. Additionally, the fixed carbon content and pore heterogeneity show a U-shaped distribution; with increasing extent of anthracitization, the heterogeneity of the filled pores is enhanced, while that of the diffusion pores remains relatively unaffected. Gray correlation analysis indicated that the heterogeneity of the filled pores is mainly affected by the basic parameters of the coal specimens and the pore structural parameters, whereas that of the diffusion pores is mainly affected by the basic parameters of the coal specimens and the degree of coalification.

This study provides meaningful insight into the pore structure of various grades of coal, and is expected to guide future research on various aspects of coalbed methane extraction.

Data availability

The data was supported for the conclusions of this research are derived from the corresponding author, in line with rightful requirements.

References

Hou, H. et al. Influence of coal petrology on methane adsorption capacity of the Middle Jurassic coal in the Yuqia Coalfield, northern Qaidam Basin, China. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 149, 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2016.10.026 (2017).

Pan, Z. & Wood, D. A. Virtual special issue: coalbed methane (CBM) exploration, reservoir characterisation, production, and modelling: a collection of published research (2009–2015). J. Natl. Gas Sci. Eng. 26, 1491–1494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2015.08.023 (2015).

Pan, H. et al. A Physical Parameter Characterizing Heterogeneity of Pore and Fracture Structures in Coal Reservoirs. Processes. 12, 1553. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12081553 (2024).

Bu, H., Ju, Y., Tan, J., Wang, G. & Li, X. Fractal characteristics of pores in non-marine shales from the Huainan coalfield, eastern China. J. Natl. Gas Sci. Eng. 24, 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2015.03.021 (2015).

Yan, J., Meng, Z., Zhang, K., Yao, H. & Hao, H. Pore distribution characteristics of various rank coals matrix and their influences on gas adsorption. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 189, 107041–107041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2020.107041 (2020).

Ma, Z. et al. Detailed Characterization of Microscopic Pore Structure in Low-Rank Coal: A Case Study of Zhalainuoer Coalfield. Natl. Resources Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-024-10355-z (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. Pore Size Distribution and Fractal Characteristics of Deep Coal in the Daning-Jixian Block on the Eastern Margin of the Ordos Basin. ACS Omega 9, 32837–32852. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c03510 (2024).

Qin, L. et al. Quantitative characterization of the pore volume fractal dimensions for three kinds of liquid nitrogen frozen coal and its enlightenment to coalbed methane exploitation. Energy 263, 125741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.125741 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. Experimental study of effect of liquid nitrogen cold soaking on coal pore structure and fractal characteristics. Energy 275, 127470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127470 (2023).

Zhang, K., Meng, Z., Liu, S., Hao, H. & Chen, T. Laboratory investigation on pore characteristics of coals with consideration of various tectonic deformations. J. Natl Gas Sci. Eng. 91, 103960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2021.103960 (2021).

Minmin, L., Weimin, L. & Gaowei, Y. Fractal and pore structure analysis of structural anisotropic coal under different impact loads. Environ. Earth Sci. 79, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-020-09071-7 (2020).

Cui, M., Li, J., Zhang, H. & Li, W. Study on the Evolution Mechanism of Permeability and Porosity of Coal under Repeated Mining Stress Path. Int. J. Geomechanics 25, 04025028. https://doi.org/10.1061/ijgnai.gmeng-10609 (2025).

Chen, X., Yao, G., Cai, J., Huang, Y. & Yuan, X. Fractal and multifractal analysis of different hydraulic flow units based on micro-CT images. J. Natl. Gas Sci. Eng. 48, 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.11.048 (2017).

Muller, J., Huseby, O. K. & Saucier, A. Influence of multifractal scaling of pore geometry on permeabilities of sedimentary rocks. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 5, 1485–1492. https://doi.org/10.1016/0960-0779(95)00025-y (1995).

Zheng, S., Yao, Y., Zhang, S., Liu, Y. & Yang, J. Insights into multifractal characterization of coals by mercury intrusion porosimetry. Energies 12, 4743. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12244743 (2019).

Zhang, J., Wei, C., Chu, X., Vandeginste, V. & Ju, W. Multifractal analysis in characterizing adsorption pore heterogeneity of middle-and high-rank coal reservoirs. ACS Omega 5, 19385–19401. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c01115 (2020).

Xie, S. et al. Fractal and multifractal analysis of carbonate pore-scale digital images of petroleum reservoirs. Marine Petroleum Geol. 27, 476–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.10.010 (2010).

Wang, D. et al. Difference between of coal and shale pore structural characters based on gas adsorption experiment and multifractal analysis. Fuel 371, 132044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.132044 (2024).

Li, Y., Lin, B., Zhang, X. & Lin, M. Study on the law of fracture development in plasma-induced broken coal. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56, 4995–5007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-023-03315-1 (2023).

Qi, L. et al. A Study on the pore structure and fractal characteristics of briquettes with different compression loads. Sustainability 14, 12148. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912148 (2022).

Zhou, S. et al. Multi-scale fractal characterizations of lignite, subbituminous and high-volatile bituminous coals pores by mercury intrusion porosimetry. J. Natl. Gas Sci. Eng. 44, 338–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2017.04.021 (2017).

Hu, B., Cheng, Y. & Pan, Z. Classification methods of pore structures in coal: A review and new insight. Gas Sci. Eng. 110, 204876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgsce.2023.204876 (2023).

Shi, X. et al. Micrometer-scale fractures in coal related to coal rank based on micro-CT scanning and fractal theory. Fuel 212, 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.09.115 (2018).

Yu, S., Bo, J., Fengli, L. & Jiegang, L. Structure and fractal characteristic of micro-and meso-pores in low, middle-rank tectonic deformed coals by CO2 and N2 adsorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 253, 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2017.07.009 (2017).

Senftle, J. & Landis, C. R. Vitrinite reflectance as a tool to assess thermal maturity. https://doi.org:https://doi.org/10.1306/TrHbk543C12. (1991).

Caniego, F., Martín, M. & SanJosé, F. Singularity features of pore-size soil distribution: singularity strength analysis and entropy spectrum. Fractals 9, 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218348X0100066X (2001).

Zhao, P. et al. Multifractal analysis of pore structure of Middle Bakken formation using low temperature N2 adsorption and NMR measurements. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 176, 312–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2019.01.040 (2019).

Halsey, T. C., Jensen, M. H., Kadanoff, L. P., Procaccia, I. & Shraiman, B. I. Fractal measures and their singularities: The characterization of strange sets. Phys. Rev. A 33, 1141. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.33.1141 (1986).

Martínez, F. S. J. et al. Multifractal analysis of discretized X-ray CT images for the characterization of soil macropore structures. Geoderma 156, 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2010.01.004 (2010).

Chhabra, A. B., Meneveau, C., Jensen, R. V. & Sreenivasan, K. Direct determination of the f (α) singularity spectrum and its application to fully developed turbulence. Phys. Rev. A 40, 5284. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.40.5284 (1989).

Ge, X., Fan, Y., Li, J. & Zahid, M. A. Pore structure characterization and classification using multifractal theory—An application in Santanghu basin of western China. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 127, 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2015.01.004 (2015).

Guoxi, C., Bo, J., Ming, L., Fengli, L. & Shaochun, X. Quantitative characterization of fracture structure in coal based on image processing and multifractal theory. Int. J. Coal Geol. 228, 103566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2020.103566 (2020).

Chhabra, A. & Jensen, R. V. Direct determination of the f (α) singularity spectrum. Phys. Rev. Letters. 62, 1327. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.62.1327 (1989).

Thommes, M. et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 87, 1051–1069. https://doi.org/10.1515/ci-2016-0119 (2015).

Dubinin, M. M. & Astakhov, V. A. in Description of Adsorption Equilibria of Vapors on Zeolites over Wide Ranges of Temperature and Pressure Vol. 102 Ch. 44, 69–85 (1971).

Dubinin, M. Modern state of the theory of gas and vapour adsorption by microporous adsorbents. Pure Appl. Chem. 10, 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1351/pac196510040309 (1965).

Hu, B. et al. New insights into the CH4 adsorption capacity of coal based on microscopic pore properties. Fuel 262, 116675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116675 (2020).

Aukett, P., Quirke, N., Riddiford, S. & Tennison, S. Methane adsorption on microporous carbons—a comparison of experiment, theory, and simulation. Carbon 30, 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-6223(92)90015-O (1992).

Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am Chem. Soc. 40, 1361–1403. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja02242a004 (1918).

Holmes, R., Rupp, E. C., Vishal, V. & Wilcox, J. Selection of shale preparation protocol and outgas procedures for applications in low-pressure analysis. Energy Fuels. 31, 9043–9051. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b01297 (2017).

Sun, B. et al. Pore size distributions and pore multifractal characteristics of medium and low-rank coals. Sci. Rep. 10, 22353. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79338-3 (2020).

Liu, K., Ostadhassan, M. & Kong, L. Multifractal characteristics of Longmaxi Shale pore structures by N2 adsorption: A model comparison. J Petroleum Sci. Eng. 68, 330–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2018.04.072 (2018).

Ferreiro, J. P. & Vázquez, E. V. Multifractal analysis of Hg pore size distributions in soils with contrasting structural stability. Geoderma 160, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2009.11.019 (2010).

Mastalerz, M., Drobniak, A. & Rupp, J. Meso-and micropore characteristics of coal lithotypes: implications for CO2 adsorption. Energy Fuels 22, 4049–4061. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef800544g (2008).

An, F.-h, Cheng, Y.-p, Wang, L. & Li, W. A numerical model for outburst including the effect of adsorbed gas on coal deformation and mechanical properties. Comput. Geotechnics 54, 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2013.07.013 (2013).

Zhang, M. et al. Determinations of the multifractal characteristics of the pore structures of low-, middle-, and high-rank coal using high-pressure mercury injection. Journal of Petroleum Sci. Eng. 203, 108656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2021.108656 (2021).

Jiang, J. et al. Effect of moisture on time-varying diffusion properties of methane in low-rank coal. Trans. Porous Media. 146, 617–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-022-01876-3 (2023).

Xiao, C. et al. Effect of Coal Rank and Coal Facies on Nanopore-Fracture Structure Heterogeneity in Middle-Rank Coal Reservoirs. ACS Omega 9, 33279–33292. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c05179 (2024).

Rodrigues, C. F. & De Sousa, M. L. The measurement of coal porosity with different gases. Int. J. Coal Geol. 48, 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-5162(01)00061-1 (2002).

Liu, Z. et al. Numerical assessment of CMM drainage in the remote unloaded coal body: Insights of geostress-relief gas migration and coal permeability. J. Natl. Gas Sci. Eng. 45, 487–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2017.06.017 (2017).

Shui, H., Lin, C., Zhang, M., Wang, Z. & Zheng, M. Comparison of the associative structure of two different types of rich coals and their coking properties. Fuel 89, 1647–1653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2009.08.011 (2010).

Lupoi, J. S. et al. Quantitative evaluation of vitrinite reflectance and atomic O/C in coal using Raman spectroscopy and multivariate analysis. Fuel 230, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.04.172 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was encouranged by the NSFC of China (52204235).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by C.W., J.Q., L.Z., D. X., J.L. The first draft of the manuscript was written by B. Z., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Zhang, B., Qiao, J. et al. Gas adsorption analysis of pore structure differences and influencing factors in coal with varying metamorphic grades. Sci Rep 15, 11793 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96123-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96123-2