Abstract

Developing accurate predictive models for pile bearing capacity on rock is crucial for optimizing foundation design and ensuring structural stability. This research presents an advanced data-driven framework that integrates multiple machine learning algorithms to predict the bearing capacity of piles based on geotechnical and in-situ test parameters. A comprehensive dataset comprising key influencing factors such as pile dimensions, geological characteristics, and penetration resistance was utilized to train and validate various models, including Kstar, M5Rules, ElasticNet, XNV, and Decision Trees. The Taylor diagram and statistical evaluations demonstrated the superiority of the proposed models in capturing complex nonlinear relationships, with high correlation coefficients and low root mean square errors indicating robust predictive capabilities. Sensitivity analyses using Hoffman and Gardener’s approach and SHAP values identified the most influential parameters, revealing that penetration resistance, pile embedment depth, and geological conditions significantly impact pile capacity. The findings underscore the effectiveness of machine learning in geotechnical engineering applications, offering a reliable and efficient alternative to traditional empirical and analytical methods. The developed framework provides engineers and practitioners with a powerful tool for improving pile design accuracy, reducing uncertainties, and optimizing construction practices. Future research should focus on expanding the dataset with diverse geological conditions and exploring hybrid modeling techniques to enhance prediction accuracy further.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The analytical and machine learning computational evaluation of the bearing capacity of piles on rock provides critical insights for the design of pile foundations, enhancing both accuracy and efficiency in geotechnical engineering1,2,3. Analytical methods typically rely on theoretical models and empirical correlations to estimate bearing capacity based on factors such as rock type, uniaxial compressive strength, pile dimensions, and rock-pile interaction mechanisms4,5,6. These approaches, though widely used, often face limitations in accounting for complex geological conditions and variability in material properties7. Machine learning methods overcome these limitations by leveraging large datasets to capture nonlinear relationships between input parameters and bearing capacity outcomes8. Algorithms such as decision trees, support vector machines, and neural networks can predict pile capacity more accurately by learning from past data, including field tests and experimental studies9. These models are particularly valuable when dealing with heterogeneous rock formations, complex boundary conditions, and incomplete datasets10. The integration of analytical and machine learning approaches provides a balanced framework for pile design11. Analytical models can guide the initial design by providing baseline estimates, while machine learning models refine these estimates by capturing site-specific factors and reducing prediction uncertainties12. This hybrid approach results in safer and more cost-effective foundation designs by minimizing the risks of underestimating or overestimating bearing capacities14. In practical applications, these computational advancements support informed decision-making in infrastructure projects, allowing engineers to optimize pile dimensions, material usage, and installation techniques5. They also contribute to sustainability by reducing material waste and enabling more accurate assessments of site conditions, leading to robust and durable foundation systems in diverse geological environments.

The bearing capacity of piles on rock is a crucial factor in geotechnical engineering, impacting the design and stability of deep foundations1. The precise prediction of this capacity is crucial for maintaining the safety and economic feasibility of structures, especially in regions where bedrock is found at shallow depths7. Conventional approaches to estimating pile bearing capacity on rock typically utilize empirical formulas, analytical solutions, and in-situ testing methods15. These methods are constrained by their dependence on simplified assumptions, variability in rock properties, and the complexity of rock-pile interactions16. Recent advancements in data-driven methodologies, including machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI), have proven effective in predicting geotechnical parameters, thereby addressing the shortcomings of traditional techniques2,17. This review offers a thorough overview of the subject, examines the difficulties in predicting pile bearing capacity on rock, and investigates the potential of data-driven frameworks to mitigate these issues18. Pile foundations serve as deep structural components that facilitate the transfer of loads from superstructures to more stable soil or rock strata located at greater depths3. The bearing capacity of piles socketed into rock is affected by several factors, including the unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of the rock, the rock mass rating (RMR), the socket length, the pile diameter, and the interface friction between the pile and the rock9. The bearing capacity of piles on rock is generally categorized into two components: end-bearing capacity and side resistance5. The end-bearing capacity originates from the resistance of the rock at the pile tip, whereas the side resistance is produced by the shear strength along the pile-rock interface.

Conventional approaches for assessing the bearing capacity of piles on rock have been extensively researched and implemented in the field of geotechnical engineering1. These methods generally rely on empirical correlations, analytical models, and field testing. Rowe and Armitage14 proposed a design method for drilled piers in soft rock that incorporates the unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of the rock and the socket length. Kulhawy and Goodman15 established a theoretical framework for estimating the side resistance of piles in discontinuous rock masses, highlighting the significance of rock mass rating (RMR) and joint characteristics. Pells16 conducted a thorough review of rock-socketed pile design, emphasizing the shortcomings of conventional methods, including their dependence on oversimplified assumptions and the challenges in accurately defining rock properties. Zhang and Einstein17 introduced an empirical approach for estimating the end-bearing capacity of drilled shafts in rock, grounded in an extensive database of pile load tests. Their method has gained extensive practical application; however, it is constrained by its dependence on site-specific data.

Traditional methods for predicting pile bearing capacity on rock encounter several challenges, despite their widespread application. Hoek and Brown18 observed that variability in rock properties, including UCS and RMR, can result in considerable uncertainties in predictions of pile capacity. Rowe and Armitage14 emphasized the challenges in accounting for the intricate interactions between the pile and the rock, especially in scenarios involving highly fractured or anisotropic rock masses. Field tests, including pile load tests and rock socket integrity tests, yield direct measurements of pile capacity; however, they tend to be costly and require significant time investment. Zhang and Xu19 highlighted the necessity for improved efficiency and cost-effectiveness in predicting pile bearing capacity, especially in large-scale projects where comprehensive field testing may be impractical.

Recently, data-driven methodologies, including machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI), have become increasingly prominent in geotechnical engineering to overcome the constraints of conventional techniques. Shahin20 illustrated the capability of artificial neural networks (ANNs) in forecasting the load-settlement behavior of piles in cohesive soils. Alkroosh and Nikraz21 utilized support vector machines (SVMs) to predict the bearing capacity of piles in cohesive soils, demonstrating that the SVM model yielded more accurate predictions compared to empirical methods. Zhang et al.22 created an ensemble learning model to estimate the bearing capacity of rock-socketed piles, utilizing data from 120 case studies. The study demonstrated that the ensemble model, integrating predictions from various machine learning algorithms, yielded greater accuracy and reliability compared to standalone models. The studies demonstrate that data-driven methods effectively capture the intricate interactions between pile and rock properties, yielding accurate predictions despite limited data availability.

Numerous studies have investigated the combination of data-driven and traditional approaches to enhance the precision and interpretability of pile capacity forecasts. Goh et al.23 utilized artificial neural networks (ANNs) to predict the ultimate load capacity of piles using data from static load tests, demonstrating that the ANN model surpassed traditional methods in prediction accuracy and robustness. Zhang and Xu19 proposed a hybrid approach that integrates data-driven and analytical methods, resulting in enhanced accuracy and interpretability of predictions. Numerous case studies have shown the efficacy of data-driven methods in predicting the bearing capacity of piles on rock. Goh et al.23 employed artificial neural networks to forecast the ultimate load capacity of piles utilizing data derived from static load tests. The authors demonstrated that the ANN model surpassed traditional methods regarding prediction accuracy and robustness. Alkroosh and Nikraz21 utilized support vector machines (SVMs) to forecast the bearing capacity of piles in cohesive soils, demonstrating that the SVM model yielded more precise predictions compared to empirical methods. Zhang et al.22 developed an ensemble learning model to predict the bearing capacity of rock-socketed piles, utilizing data from 120 case studies. The study demonstrated that the ensemble model, integrating predictions from various machine learning algorithms, yielded greater accuracy and reliability compared to standalone models. The case studies demonstrate the potential of data-driven methods to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of pile design. Recent research has concentrated on the validation of machine learning models using real-world data. Park et al.24 conducted a comparison between machine learning-based predictions and static load test results, attaining an accuracy exceeding 90%. Fattah et al.25 demonstrated enhanced prediction efficiency through the use of hybrid machine learning models that integrate geotechnical parameters. Additional studies have integrated real-time sensor data into machine learning frameworks, facilitating ongoing monitoring and enhancement of predictive models. Large-scale infrastructure project case studies demonstrate that data-driven models can enhance foundation design, simultaneously minimizing costs and uncertainties.

Statement of research innovation

This research introduces an innovative approach to predicting the bearing capacity of piles on rock by leveraging advanced data-driven methodologies, including machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI), to overcome the limitations of conventional empirical and analytical methods. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on simplified assumptions, site-specific empirical correlations, and costly in-situ testing, this study explores the capability of ML models to capture the complex interactions between rock and pile properties with greater accuracy and efficiency. By integrating various advanced ML techniques, including Semi-supervised classifier (Kstar), M5 classifier (M5Rules), Elastic net classifier (ElasticNet), Correlated Nystrom Views (XNV), and Decision Table (DT), the research aims to enhance prediction reliability while reducing the dependency on extensive field testing. Additionally, the study investigates hybrid methodologies that combine ML with analytical frameworks, ensuring both interpretability and precision in pile capacity estimation. The innovation lies in the ability of these data-driven approaches to process large-scale datasets, identify intricate patterns in geotechnical parameters, and provide cost-effective, accurate predictions that improve foundation design and stability. This research advances the field by validating ML-based models using real-world case studies and demonstrating their potential to enhance geotechnical engineering practices, ultimately contributing to safer and more economically viable deep foundation solutions.

Methodology

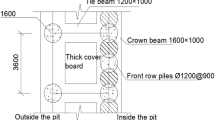

Data collection from experimental setup and preliminary analysis

A comprehensive literature was applied in this research work and 200 multiple data entries from experimental exercises were collected from literature1. The collected 200 records were partitioned into training set (150 records = 75%) and validation set (50 records = 25%) in line with optimal partitioning pattern for reliable models26. The studied critical factors of this research included; the diameter of the pile (D), the initial soil exploration’s depth in meters (DSE1), the second soil exploration’s depth (meters) (DSE2), the third soil exploration (DSE3)’s depth (meters), the Phreatic Surface (PTE) is the depth in meters at which the groundwater table is located, the depth in meters of the effective stress point (Ge), the depth in meters of the expected phreatic surface (EPTE), the depth of the anticipated elastic settling point (Pe) (meters), the quantity of standard penetration tests (SPTs) measured at different depths, at every depth, and the standard penetration test blows count (SPTt), which are applied as input parameters. The maximum bearing capacity at the foundation level (Pu ) expressed in kilo Newton (kN) is the output. Table 1 summarizes their statistical characteristics. The statistical analysis of the training and validation datasets provides insights into the variability and distribution of the parameters influencing pile bearing capacity on rock. The maximum and minimum values indicate the range of data considered for both sets, showing a significant spread in the key variables such as pile displacement (D), pile embedment depths (DSE1, DSE2, DSE3), penetration test values (SPTs, SPTt), and ultimate pile capacity (Pu). The mean values (Avg) of the datasets reveal slight differences between the training and validation sets, with the validation set having a slightly higher average in most parameters, particularly in Pu, which suggests a slight increase in the predicted bearing capacity in the validation phase27. The standard deviation (SD) and variance (Var) highlight the dispersion of data around the mean. For both training and validation sets, the highest SD is observed in Pu, indicating a wide spread in the pile capacity values. Similarly, parameters such as DSE2, Pe, and SPTs exhibit relatively high SDs, implying considerable variation in pile socketing and soil resistance characteristics. The variance of Pu in the validation set (0.29) is slightly lower than that in the training set (0.35), suggesting a reduction in variability, possibly due to the influence of improved model generalization. Comparing the two datasets, it is evident that the validation set exhibits slightly lower variability in most parameters, as shown by lower SD and variance values. The consistency between the training and validation datasets suggests that the data-driven model was trained on a well-balanced dataset, which supports reliable generalization. The minor differences in statistical metrics between the two datasets indicate that the model is not significantly overfitting, maintaining a good level of predictive accuracy and robustness in estimating the pile bearing capacity on rock. Finally, Figs. 1 and 2 show the violin sketch and the Pearson correlation matrix, histograms, and the relations between variables. The violin plot visualizes the distribution and density of various input parameters influencing the pile bearing capacity on rock. The shape of each violin provides insights into the spread and frequency of data points for each variable. Wider sections indicate higher density, while narrower regions suggest lower frequency. The plot for pile displacement (D) shows a bimodal distribution, with two main density peaks around 300 mm and 400 mm, indicating that most data points are concentrated in these regions. DSE1 and DSE2 exhibit multiple peaks, implying the presence of different clusters in the dataset, possibly due to varying geological conditions. DSE3 has a skewed distribution, with a dominant peak near zero, suggesting that a significant portion of the dataset has low values for this parameter. The Ge parameter exhibits a concentrated and narrow density distribution, which implies low variability in geological characteristics across the dataset. The PTE, EPTE, and Pe parameters show multimodal distributions, indicating that multiple factors influence their values, leading to different clusters of data points. SPTs and SPTt display distinct density variations, with a broad range of values and peaks at different intervals, suggesting the presence of varying subsurface conditions affecting standard penetration test results. The most critical parameter, Pu (pile bearing capacity), demonstrates a complex distribution with multiple peaks and a wide spread of values, indicating significant variability in the dataset. This suggests that pile bearing capacity is influenced by multiple interacting factors rather than a single dominant parameter. The violin plots overall confirm that the dataset consists of diverse input conditions, with varying levels of skewness and multimodality, highlighting the importance of advanced predictive models to capture these complexities in pile capacity estimation. Conversely, the correlation matrix visually represents the relationships between different variables influencing the pile bearing capacity on rock. The color-coded heatmap highlights the strength and direction of correlations, with red indicating strong positive correlations, green representing strong negative correlations, and yellow reflecting moderate relationships. The highest positive correlations are observed between Pe and SPTs (0.97), SPTs and Pu (0.85), and Pe and Pu (0.79), indicating that these parameters strongly influence pile bearing capacity. Conversely, PTE exhibits strong negative correlations with D (−0.71), DSE1 (−0.94), and Pu (−0.78), suggesting that higher PTE values correspond to lower pile capacity and displacement. The scatter plots provide additional insights into variable relationships. Strong positive correlations, such as between Pe and SPTs, show clear upward trends, while strong negative correlations, such as between PTE and Pu, exhibit downward patterns. Some parameters, such as Ge and Pu (−0.34), show weaker correlations, indicating less direct influence. The histograms along the diagonal illustrate the distribution of each variable, with D, Pe, and Pu showing right-skewed distributions, suggesting that most values are concentrated towards the lower end of the range. The overall interpretation of the chart highlights the significant impact of SPTs, Pe, and PTE on Pu, confirming their importance in predicting pile bearing capacity. Strong positive correlations between Pe, SPTs, and Pu suggest that penetration resistance plays a crucial role in determining pile performance, while the negative influence of PTE underscores the importance of soil and geological conditions. The insights derived from the correlation matrix provide valuable guidance for developing advanced predictive models by emphasizing the most influential factors.

Plan of research

Five (5) different ML techniques were used to predict (Pu) using the collected database. These techniques are “Semi-supervised classifier (Kstar)”, “M5 classifier (M5Rules), “Elastic net classifier (ElasticNet), “Correlated Nystrom Views (XNV)”, and “Decision Table (DT)”. All the models were created using “Weka Data Mining” software version 3.8.6. Further the models’ performance evaluation and sensitivity analyses were conducted and reported.

Theoretical framework

Semi-supervised classifier (Kstar)

Kstar is a semi-supervised instance-based classifier that uses an entropy-based distance function to classify data points. It generalizes the k-nearest neighbor approach by computing the probability of transforming one instance into another through a series of steps, rather than relying solely on Euclidean distance27. This transformation-based distance function allows Kstar to adapt to diverse data structures and distributions, making it more flexible and effective in handling noisy or complex datasets. The model operates by evaluating the similarity between the target instance and training examples based on these transformation probabilities. By leveraging both labeled and unlabeled data, Kstar improves classification accuracy and generalization performance, especially in situations where fully labeled datasets are limited28. Its robust performance and adaptability make it suitable for applications requiring enhanced predictive power in complex environments. The probability of transformation P(x→y) is defined as the probability of transforming instance x to y. The computation involves all possible transformations.

Where Pt represents the probability of each transformation step. The distance between two instances x and y is given by:

The class of the neighbors nearest to it is applied for classification. The most probable class is determined using:

Where: “wi” is the weight of the neighbor xi and P(xi→x)is the probability of transformation.

M5 classifier (M5Rules)

M5Rules is a rule-based regression model derived from the M5 model tree algorithm. It combines decision tree structures and linear regression models to predict continuous outcomes. The model first builds an M5 model tree by recursively splitting the dataset based on input attributes and fitting linear regression models at the leaves28. These branches are then converted into a set of transparent and interpretable decision rules. Each rule generated by M5Rules represents a specific region in the input space and is associated with a linear regression equation to predict the target variable. This combination of rules and regression equations allows M5Rules to handle complex, nonlinear relationships while maintaining interpretability29. It is particularly useful for applications requiring both accurate predictions and insights into how the predictions are made. Each leaf node applies an equation of regression:

Where β0 is the intercept, βi are the coefficients, and xi are the input features. The decision tree splits are evaluated by minimizing the variance in the target variable y:

Elastic net classifier (ElasticNet)

The ElasticNet classifier is a regularized machine learning algorithm that combines the strengths of L1 (lasso) and L2 (ridge) penalties for feature selection and model optimization. It addresses limitations such as multicollinearity and overfitting by balancing feature selection and coefficient shrinkage. The ElasticNet classifier is particularly effective when dealing with high-dimensional datasets where predictors may be highly correlated29. The model introduces two hyperparameters: alpha, which controls the overall strength of regularization, and the mixing ratio (lambda) that determines the weight between L1 and L2 penalties. By tuning these parameters, ElasticNet finds an optimal solution that benefit from both sparse feature selection (due to L1) and smooth coefficient adjustment (due to L2). ElasticNet is widely used in applications where interpretability and performance are critical, such as text classification, bioinformatics, and predictive analytics involving complex feature sets. Its flexibility and robustness make it a versatile choice for both classification and regression tasks. Particularly, it is useful when features are correlated. The objective function:

\(\:{{\parallel}\beta\:{\parallel}}_{1}:L1\:norm\:\left(lasso\:penalty\right)\). \(\:{{\parallel}\beta\:{\parallel}}_{2}^{2}:L2\:norm\:\left(ridge\:penalty\right)\). \(\:\lambda\:\): Regularization parameter. \(\:\propto\:\): Mixing parameter (0\(\:\le\:\alpha\:\le\:1)\). Elastic Net uses coordinate descent to optimize the coefficients β.

Correlated Nystrom views (XNV)

Correlated Nyström Views (XNV) is a machine learning technique that extends the traditional Nyström method by incorporating multi-view learning to enhance the approximation of large kernel matrices. The Nyström method is commonly used for efficient kernel learning by selecting a subset of data points to approximate the full kernel matrix, reducing computational complexity. XNV improves this process by leveraging correlated views, where different subsets of features or data perspectives provide complementary information30. By integrating these views, XNV captures richer data patterns and relationships, leading to more accurate approximations and improved model performance. This approach is particularly valuable in applications with heterogeneous data sources, such as multimedia analysis, sensor fusion, and bioinformatics, where correlated information from multiple feature sets can significantly enhance learning outcomes. Using linked embeddings, it integrates several data views (such as feature sets). Nystrom Approximation for Kernel Matrix K:

Where: C: Submatrix of K (columns corresponding to sampled points). W: Submatrix of K (intersection of rows and columns of sampled points). \(\:{W}^{\dag}\) Pseudoinverse of W. Correlated Nystrom Views combines the embeddings from different views using a correlation matrix R:

Where: \(\:{Z}_{i}\): Embedding from the i-th view, R: Correlation matrix learned during training. The embeddings Z are fed into a classifier (e.g., SVM or logistic regression).

Decision table (DT)

A Decision Table (DT) is a simple, rule-based machine learning model used for classification and decision-making tasks. It organizes input features and corresponding outcomes in a tabular format, where each row represents a unique combination of conditions that lead to a specific decision or prediction27. The table explicitly lists all possible conditions and their associated actions, making it highly interpretable. DT models are particularly useful when the decision-making process can be clearly defined by straightforward rules31. They are efficient in scenarios with limited feature interactions and well-structured datasets. However, they may struggle with complex or noisy data where advanced models such as decision trees or ensemble methods often perform better. Despite their simplicity, DTs are valued for their transparency, ease of implementation, and suitability for explainable AI applications. Each row in the decision table corresponds to a rule: If \(\:{A}_{1}={v}_{1}\) and \(\:{A}_{2}={v}_{2}\) and … then Class = c. When multiple rows match, the class is determined by majority voting:

Where: \(\:\parallel\:\) is the indicator function.

Performance evaluation

The accuracies of developed models were evaluated by comparing SSE, MAE, MSE, RMSE, Error %, Accuracy % and R2, R, WI, NSE, KGE and SMAPE between predicted and calculated bearing capacity values. The definition of each used measurement is presented in Eq. 10 to 20.

MAE

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is a metric used to measure the average magnitude of errors between predicted and actual values in regression models. It calculates the absolute difference between the predicted and observed values, providing a straightforward assessment of model accuracy. MAE is defined by the formula:

Where: yi represents the actual values, xi denotes the predicted values, and N is the total number of observations. MAE is easy to interpret as it retains the same units as the target variable and directly indicates the average error per prediction. It is less sensitive to outliers compared to metrics like Mean Squared Error (MSE) since it does not square the error terms. However, it treats all errors equally, regardless of their size or direction.

MSE

Mean Squared Error (MSE) is a widely used metric for evaluating the accuracy of regression models by measuring the average of the squared differences between predicted and actual values. It is defined by the formula:

MSE penalizes larger errors more heavily due to the squaring of error terms, making it particularly sensitive to outliers. It provides a comprehensive measure of model accuracy by emphasizing significant deviations. However, since it uses squared units, its interpretation may be less intuitive compared to other metrics like MAE. MSE is commonly minimized during model training to improve prediction accuracy.

RMSE

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is a performance metric used in regression analysis to measure the standard deviation of prediction errors. It represents the square root of the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and is calculated as:

RMSE provides an intuitive measure of how much the predictions deviate from the actual values on average and retains the same units as the target variable. Its sensitivity to large errors makes it useful for emphasizing significant deviations. While RMSE offers a more interpretable measure compared to MSE, it is susceptible to outliers due to the squaring of error terms.

Error

Error in machine learning refers to the difference between the predicted value generated by a model and the actual observed value. It quantifies the accuracy of a model by indicating how far off the predictions are from the true outcomes. The error can be positive or negative depending on whether the prediction overestimates or underestimates the target. It is represented by:

Minimizing errors is the primary objective during model training to improve prediction accuracy.

Accuracy

Accuracy is a performance metric used in classification tasks to measure the proportion of correctly predicted instances out of the total number of predictions. It is calculated as:

Accuracy is straightforward and provides a general sense of model performance. However, it may be misleading for imbalanced datasets where one class dominates, as it does not account for the distribution of errors across classes. In such cases, metrics like precision, recall, or F1-score may be more appropriate.

Coefficient of determination (R2)

The coefficient of determination (R2) is a statistical measure used in regression analysis to indicate how well the independent variables explain the variance in the dependent variable. It is calculated as:

The value of R2 ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates a perfect fit and 0 implies that the model explains none of the variance in the data. Negative values can occur when the model performs worse than simply predicting the mean of the dependent variable. R2 provides insight into the goodness of fit but does not assess the accuracy of individual predictions or model complexity.

Coefficient of correlation (R)

The coefficient of correlation (R) measures the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables. It is calculated as:

A higher magnitude of R suggests a stronger correlation, while its sign indicates whether the relationship is direct or inverse.

WI

The Willmott Index of Agreement (WI) is a statistical metric used to assess the accuracy of model predictions compared to observed values. It quantifies the degree to which predictions match observations and ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates a perfect match and 0 signifies complete disagreement. WI is computed as:

WI accounts for both the magnitude and direction of errors, making it a robust indicator for evaluating model performance. Unlike traditional metrics such as RMSE, it is less sensitive to large errors and provides a more balanced evaluation of prediction accuracy.

NSE

The Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) is a statistical metric used to assess the predictive accuracy of hydrological models by comparing observed and predicted values. It is defined as:

NSE ranges from −∞ to 1, with 1 indicating a perfect match between predictions and observations. A value of 0 implies that the model predictions are as accurate as using the mean of the observed data, while negative values indicate that the model performs worse than the mean. NSE is widely used in environmental and hydrological studies to evaluate model efficiency and performance.

10 KGE

The Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) is a performance metric used to assess the accuracy of model predictions, particularly in hydrology and environmental modeling. It provides a balanced evaluation by combining correlation, bias, and variability components. KGE is defined as:

KGE ranges from −∞ to 1, with 1 indicating perfect agreement between predictions and observations. It improves upon traditional metrics like NSE by addressing limitations related to bias and variability, offering a comprehensive evaluation of model performance.

11 SMAPE

Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE) is a metric used to measure the accuracy of forecasts by calculating the percentage difference between predicted and actual values. It is defined as:

SMAPE provides a normalized error percentage, making it useful for comparing performance across different datasets. It treats overestimations and underestimations symmetrically, hence the “symmetric” aspect of the metric31,32. SMAPE values range from 0% (perfect prediction) to 200%, with lower values indicating better model performance. It is particularly suited for cases where both small and large magnitudes are important.

Sensitivity analyses

Hoffman and Gardener’s method evaluates the sensitivity of input factors by directly perturbing each variable within its range and measuring the resulting changes in the model’s output. It provides a straightforward and quantitative assessment of the contribution of each factor to variations in the output. This method often highlights linear relationships and assumes independence among factors, making it effective for simple systems but less suited for capturing complex, nonlinear interactions33. Conversely, SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) is a game-theoretic approach that calculates the marginal contribution of each input factor by considering all possible combinations of inputs34. Unlike Hoffman and Gardener’s method, SHAP accounts for variable interactions and dependencies, providing a comprehensive view of how input factors influence the model’s predictions. By distributing the total prediction difference among the input factors, SHAP assigns a fair importance value to each variable, offering a more nuanced and interpretable sensitivity analysis for complex machine learning models. A preliminary sensitivity analysis was carried out on the collected database to estimate the impact of each input on the (Y) values. “Single variable per time” technique is used to determine the “Sensitivity Index” (SI) for each input using both the Hoffman & Gardener’s33 and SHAP’s34,35 methods formula as follows:

A sensitivity index of 1.0 indicates complete sensitivity, a sensitivity index less than 0.01 indicates that the model is insensitive to changes in the parameter34.

Results presentation and analysis

Kstar models

The KStar model hyperparameters (see Fig. 3) displayed in the image control various aspects of its behavior, influencing its performance and predictive accuracy. The batchSize is set to 100, meaning the model processes data in batches of 100 instances at a time, which can affect computational efficiency and memory usage. The debug parameter is set to False, indicating that debugging messages are not enabled, leading to a cleaner output but potentially making it harder to diagnose issues during execution. The doNotCheckCapabilities parameter is also set to False, meaning the model will verify its capabilities before execution, ensuring compatibility with the dataset. The entropicAutoBlend parameter is set to False, meaning entropy-based automatic blending is disabled, which may impact how the model determines similarity between instances. The globalBlend value is set to 20, meaning the model will apply a global blending factor of 20 to influence the similarity measure, which can affect classification accuracy. The missingMode parameter is set to “Average column entropy curves,” suggesting that missing values will be handled using entropy-based averaging, which is an advanced technique for managing missing data. Finally, numDecimalPlaces is set to 2, meaning numerical results will be rounded to two decimal places, ensuring consistency in output formatting. The best fit plot for the Kstar model demonstrates a strong correlation between the predicted and experimental values in both training and validation datasets. The regression equations for training (y = 0.97x + 27.95) and validation (y = 0.99x + 20.31) indicate a nearly perfect linear relationship between predicted and actual values, with slopes close to 1 (see Fig. 4). The coefficient of determination (R² = 0.98) in both cases further confirms the high predictive accuracy of the model. When compared with the Kstar performance data in the table, the statistical indices align with the observations from the best fit plot. The model has the lowest Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), reinforcing its precision. The low error percentage (4%) and high accuracy (96%) indicate minimal deviations between predictions and actual values. The model’s strong performance is further supported by high values of R², correlation coefficient (R = 0.99), Willmott’s Index (WI = 1.00 in training and 0.99 in validation), Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), and Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE), all reflecting near-optimal predictive capability. The best fit plot also shows that most predicted values lie within the ± 15% error margins, signifying the model’s robustness and reliability in predicting pile bearing capacity. The experimental and predicted values align closely along the red best-fit line, with minimal scatter, further validating the consistency of the Kstar model.

M5Rules models

The M5Rules model hyperparameters (see Fig. 5) in the image influence rule-based regression tree behavior. The batchSize is set to 100, meaning the model processes data in chunks of 100 instances at a time, affecting efficiency and memory use. The buildRegressionTree parameter is set to False, indicating that the model will not construct a full regression tree but will instead generate rule-based models. The debug parameter is False, meaning debugging messages are disabled for a cleaner output. The doNotCheckCapabilities parameter is also False, ensuring the model checks its capabilities before execution to prevent errors. The minNumInstances is set to 4.0, meaning each rule must have at least four instances in the dataset to be considered valid, preventing overfitting by ensuring rules are based on sufficient data. The numDecimalPlaces is set to 4, ensuring output values are rounded to four decimal places for precision. The unpruned parameter is set to False, meaning pruning is enabled, reducing model complexity by eliminating less significant rules. The useUnsmoothed parameter is False, indicating that smoothing techniques are applied to improve the accuracy of numeric predictions by avoiding abrupt changes in rule values. The best fit plot for the M5Rules model shows a strong but slightly lower correlation between predicted and experimental values compared to the Kstar model. The regression equations for training (y = 0.92x + 78.63) and validation (y = 0.93x + 75.82) indicate a slight underestimation of higher values (see Figs. 6 and 7). The coefficient of determination (R²) values of 0.94 for training and 0.93 for validation confirm a high predictive performance but with more deviation compared to Kstar. The table data supports these observations. The M5Rules model has higher SSE, MAE, and RMSE values than Kstar, indicating greater error in predictions. The error percentage (8%) and accuracy (92%) suggest a reliable but less precise performance. The correlation coefficient (R = 0.97) and high Willmott’s Index (WI = 0.98) signify strong predictive capability, although slightly lower than Kstar. The Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) and Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) values also indicate good performance but with more deviation. The best fit plot shows a wider spread of data points compared to Kstar, meaning some predictions deviate more from the experimental values. While most predictions fall within the ± 15% error range, the larger scatter and higher intercept values suggest that the model may introduce bias, particularly for lower values. Overall, M5Rules is a strong model but exhibits slightly higher errors and more variation in predictions compared to Kstar.

ElasticNet models

The ElasticNet model hyperparameters (see Fig. 8) in the image influence the balance between L1 (lasso) and L2 (ridge) regularization, along with model optimization settings. The alpha parameter is set to 0.001, controlling the regularization strength, where smaller values allow more flexibility in fitting the data. The batchSize is 100, meaning data is processed in chunks of 100 instances, affecting efficiency. The custom_lambda_sequence field is empty, indicating that the model uses default lambda values rather than a custom sequence. The debug parameter is False, disabling debugging messages. The doNotCheckCapabilities is False, ensuring the model checks its capabilities before execution to prevent errors. The epsilon value is 1.0E-4, setting the precision threshold for convergence, meaning the model stops iterating when improvements become smaller than this value. The maxIt parameter is 10,000,000, defining the maximum number of iterations, ensuring the model does not stop prematurely before converging. The numDecimalPlaces is set to 2, meaning output values will be rounded to two decimal places. The numInnerFolds is 10, indicating that 10-fold cross-validation is applied internally for model tuning. The numModels parameter is 100, meaning the model evaluates 100 different sub-models during the learning process. The sparse parameter is False, meaning a dense representation is used instead of sparse matrices, which can impact memory usage and efficiency. The threshold is set to 1.0E-7, defining a numerical stability limit to handle very small values during computation. The use_method2 is True, indicating an alternative method is applied for optimization. The use_stderr_rule is False, meaning the model does not rely on the standard error rule for model selection, instead choosing based on direct performance metrics. The best fit plot for the ElasticNet model shows a weaker correlation between predicted and experimental values compared to Kstar and M5Rules. The regression equations for training (y = 0.74x + 269.57) and validation (y = 0.70x + 339.19) indicate significant underestimation, as both slopes are much lower than 1, and the intercept values are high (see Fig. 9). The coefficient of determination (R²) values of 0.80 for training and 0.78 for validation confirm lower predictive performance, meaning the model struggles with accurately capturing the relationship between input and output variables. The table data aligns with these observations. ElasticNet exhibits the highest SSE, MAE, MSE, and RMSE values, signifying larger prediction errors. The error percentage is 13% for training and 14% for validation, making it the least accurate model in comparison. The accuracy of 87% in training and 86% in validation is lower than the other models. The correlation coefficient (R = 0.89 in training and 0.88 in validation) further confirms the weaker relationship between predicted and actual values. Willmott’s Index (WI = 0.94) and Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE = 0.80) also indicate reduced predictive reliability. The best fit plot shows a more dispersed distribution of points, especially at higher experimental values, where predictions seem to saturate and cluster. Many points fall outside the ± 15% error range, reinforcing that the model struggles with generalization. The high intercept values suggest that ElasticNet tends to introduce a systematic bias, consistently over-predicting lower values and under-predicting higher values. The Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE = 0.80) and SMAPE (12.71 in training and 11.61 in validation) further support that the model has difficulty producing accurate predictions. Overall, the ElasticNet model demonstrates the weakest predictive performance among the evaluated models, with substantial errors, lower accuracy, and a clear trend of underestimation. It may require further tuning or an alternative approach to improve prediction quality.

Pu = 4.209D + 9.34DSE1 + 23.7 DSE2 + −1.35 DSE3 −8.48 PTE + 0.332 Ge + 6.63 EPTE + 23.13 Pe + 30.75 SPTs + 5.49SPTt − 1401.3 (22).

XNV model

The XNV model hyperparameters (see Fig. 10) in the image indicate the configuration of a kernel-based machine learning approach. The regularization parameter gamma is set to 0.01, which controls the influence of each training example in a radial basis function (RBF) kernel. A sample size for the Nyström method of 100 suggests that an approximation technique is used to speed up kernel computations by sampling a subset of the data. The kernel function chosen is RBFKernel, with additional parameters (-C 250007 -G 0.01), where C likely represents the regularization parameter and G represents gamma for the kernel function. The do not apply standardization parameter is set to False, meaning data preprocessing includes standardization. The batchSize is set to 100, indicating that data is processed in chunks of 100 instances at a time. The debug parameter is False, disabling debugging messages. The doNotCheckCapabilities is False, ensuring that the model verifies its compatibility with the dataset before execution. The numDecimalPlaces is set to 2, meaning numerical results are rounded to two decimal places. The seed value is 1, ensuring reproducibility by initializing the random number generator with a fixed value. The best fit plot for the XNV model indicates a strong correlation between predicted and experimental values, but with slight underestimation. The regression equations for training (y = 0.91x + 89.49) and validation (y = 0.92x + 91.77) suggest that the model tends to predict slightly lower values than the actual experimental results, as the slopes are marginally below 1 (see Fig. 11). The coefficient of determination (R²) values of 0.93 for training and 0.91 for validation confirm a high level of predictive accuracy, though not as strong as Kstar. The table data supports this analysis. The sum of squared errors (SSE) for training is 1,496,549 and for validation is 469,551, which are considerably lower than those of ElasticNet but higher than those of Kstar. The mean absolute error (MAE) values of 77.71 kN in training and 79.16 kN in validation indicate moderate error levels. The mean squared error (MSE) and root mean squared error (RMSE) values are also relatively high, showing that the model has some degree of deviation from the actual values. Despite these errors, the model maintains an overall accuracy of 92% for training and 91% for validation. The correlation coefficient (R) values of 0.96 further indicate a strong relationship between predicted and actual values. Willmott’s Index (WI = 0.98) and Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE = 0.93) confirm that the model performs well in predicting bearing capacity. The Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE = 0.94) further suggests that the model has a reliable predictive ability. The symmetric mean absolute percentage error (SMAPE) values of 7.79 for training and 7.02 for validation show that the model maintains reasonable accuracy, with better performance in validation. The best fit plot visually confirms that the predictions align closely with the experimental values, with most data points falling within the ± 15% error range. However, there is still some scatter at higher values, indicating that the model slightly underestimates larger pile bearing capacities. The relatively small intercept values suggest that the model does not introduce significant bias. Overall, the XNV model demonstrates solid predictive performance, ranking below Kstar but performing better than ElasticNet and M5Rules. While it slightly underestimates the bearing capacity, its strong correlation metrics and low error rates make it a reliable choice for predictions.

DT models

The DT model hyperparameters (see Fig. 12) indicate a decision tree-based approach with specific configurations. The batchSize is set to 100, meaning the model processes data in batches of 100 instances at a time. The crossVal parameter is set to 2, indicating a two-fold cross-validation strategy for model evaluation. The debug parameter is False, meaning debugging messages are disabled. The displayRules parameter is set to True, enabling the display of decision rules derived from the model. The doNotCheckCapabilities parameter is False, ensuring the model checks for compatibility with the dataset before execution. The evaluationMeasure defaults to accuracy for discrete class problems and RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) for numerical class problems, which determines how model performance is measured. The numDecimalPlaces is set to 2, meaning numerical results are rounded to two decimal places. The search parameter is set to BestFirst with options -D 1 -N 5, indicating a best-first search strategy for feature selection, with D 1 likely specifying the direction and N 5 setting a limit on the number of consecutive non-improving nodes before termination. The useIBk parameter is False, meaning that the IBk instance-based learning algorithm is not used in this configuration. The DT model framework (see Fig. 13) is structured to evaluate classification or regression performance using key statistical measures. The table consists of multiple metrics such as DESIR, PTIK, SPITs, and Fn, each representing different aspects of model evaluation. The DESIR values indicate decision tree stability and performance across different conditions, while PTIK represents probabilistic tree information, helping assess uncertainty and accuracy in classification. SPITs provide a statistical breakdown of the tree’s split effectiveness, showcasing how well the model partitions the dataset into meaningful subsets. Fn appears to be a performance percentage, likely reflecting accuracy, precision, or recall depending on the specific context. The table values suggest a comparative approach where different configurations or datasets are analyzed to determine optimal decision tree efficiency. The best fit plot for the DT (Decision Tree) model shown in Fig. 14, demonstrates a strong correlation between the predicted and experimental values, with the regression equations indicating a slight underestimation of the pile bearing capacity. The training equation, y = 0.93x + 67.10, and the validation equation, y = 0.94x + 77.52, show that the model’s predictions closely follow the experimental values, though the slopes slightly deviate from 1, suggesting minor underestimation. The R² values of 0.94 for training and 0.91 for validation confirm that the DT model has a strong predictive ability, though it performs slightly worse in validation. The table data further supports this conclusion. The SSE values for training (1,180,235) and validation (469,016) are relatively low, indicating a good fit. The MAE values of 66.65 kN in training and 78.16 kN in validation suggest that the model maintains a reasonable error level, with slightly higher errors in validation. The MSE and RMSE values also align with the graphical observation, showing that while the model’s error is moderate, it remains within an acceptable range. The overall accuracy of 93% in training and 91% in validation further reinforces the model’s strong predictive capability. The correlation coefficient (R = 0.97 for training, 0.96 for validation) indicates a strong linear relationship between experimental and predicted values. Willmott’s Index (WI = 0.98), Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE = 0.94 for training, 0.91 for validation), and Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE = 0.95) all confirm that the model performs well in predicting pile bearing capacity. The SMAPE values of 6.98 in training and 6.94 in validation indicate a relatively low percentage error, making it one of the better-performing models. The best fit plot visually confirms these statistical findings. Most of the data points fall within the ± 15% error range, showing that the DT model provides predictions that are generally accurate with minimal deviation. However, as seen in the plot, some scatter exists at higher values, similar to other models like XNV. The relatively small intercept values (67.10 for training and 77.52 for validation) suggest that the model introduces only a minimal bias. Overall, the DT model shows excellent predictive performance, ranking slightly below Kstar but competing well with XNV. While it slightly underestimates higher pile bearing capacities, its strong correlation metrics, high accuracy, and low error rates make it a reliable model for predicting pile capacity.

Comparative analysis

The overall performance evaluation of models in predicting the bearing capacity of piles is analyzed based on several statistical indices, measuring accuracy, error, and reliability. Kstar outperforms other models with the lowest Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), indicating minimal deviation between predicted and actual values is shown in Table 2. Its Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Squared Error (MSE) are also the lowest among all models, reinforcing its accuracy. The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for Kstar remains the lowest at 40.02 kN in training and 49.33 kN in validation, confirming its strong predictive ability. Kstar also achieves the lowest percentage error (4%) and the highest accuracy (96%), demonstrating superior model performance. Its Coefficient of Determination (R²) is 0.98, indicating a near-perfect fit, with a correlation coefficient (R) of 0.99. Willmott’s Index (WI) reaches 1.00 in training and 0.99 in validation, further supporting Kstar’s predictive consistency. Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) and Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) values remain high at 0.98–0.99, while the Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE) is the lowest at 3.02–3.34 kN, further proving its reliability. M5Rules shows a moderate performance with significantly higher SSE, MAE, and MSE values than Kstar. Its RMSE values are 81.29 kN for training and 85.66 kN for validation, indicating larger errors. The model exhibits an 8% error and 92% accuracy, which, while decent, falls behind Kstar. R² is lower at 0.93–0.94, and R is slightly lower at 0.97. WI, NSE, and KGE remain around 0.93–0.95, showing a moderate fit. The SMAPE values of 6.22–7.27 kN indicate a higher level of error than Kstar. Elastic Net performs the worst among all models, exhibiting the highest SSE, MAE, and MSE values. Its RMSE is significantly higher at 143.56 kN in training and 156.62 kN in validation, reflecting substantial prediction errors. The model’s error percentage is the highest at 13–14%, while accuracy is the lowest at 86–87%. R² is relatively weak at 0.78–0.80, and R values remain lower at 0.88–0.89. WI and NSE decline to 0.77–0.80, showing a weaker predictive fit. KGE values also remain the lowest, while SMAPE at 11.61–12.71 kN confirms its high relative error, making it the least effective model for pile capacity prediction. XNV performs comparably to M5Rules but exhibits higher errors. SSE, MAE, and MSE are higher, while RMSE values stand at 86.50 kN for training and 96.91 kN for validation. Prediction error is 8–9%, with an accuracy of 91–92%. R² and R remain strong at 0.91–0.93 and 0.96, respectively. WI, NSE, and KGE are slightly lower than M5Rules, indicating a moderate model fit. SMAPE values at 7.02–7.79 kN suggest slightly higher relative error. DT presents a slightly better performance than XNV with lower RMSE (76.82 kN for training and 96.85 kN for validation) and lower prediction errors at 7–9%. Accuracy is slightly higher at 91–93%. R² and R values remain strong at 0.91–0.94 and 0.96–0.97, respectively. WI, NSE, and KGE are marginally better than XNV, showing that DT provides relatively reliable predictions. The SMAPE values of 6.94–6.98 kN indicate moderate error levels. Overall, Kstar is the most effective model for predicting pile bearing capacity, with the highest accuracy, lowest errors, and strongest statistical indices. DT follows closely behind, showing better performance than XNV and M5Rules. XNV and M5Rules provide moderate predictive abilities, while Elastic Net performs the worst, exhibiting the highest error rates and lowest accuracy. The Taylor charts for both training and validation phases presented in Fig. 15 illustrate the comparative performance of the predictive models using three statistical metrics: standard deviation, correlation coefficient, and root mean square error (RMSE). The measured values are represented at the reference point, and the models are plotted based on their respective standard deviations and correlation coefficients. In the training phase, models such as M5Rules, XNV, and DT exhibit higher correlation coefficients (closer to 0.95–0.99), indicating strong agreement with the measured data. These models also have relatively low RMSE values, as seen by their positioning closer to the reference point. ElasticNet, however, shows lower performance with a reduced correlation coefficient and higher RMSE, suggesting it is less effective in capturing the variability of the dataset. For the validation phase, the trend remains consistent, with M5Rules, XNV, and DT maintaining their strong correlation coefficients and relatively low RMSE values, confirming their robustness in generalizing to unseen data. KStar and ElasticNet demonstrate weaker correlation coefficients and higher RMSE values, suggesting they struggle more with predictive accuracy and reliability. Overall, the Taylor charts confirm that M5Rules, XNV, and DT are the best-performing models in both training and validation, with high correlation to measured data and lower prediction errors. ElasticNet performs the worst, as indicated by its lower correlation and higher RMSE. These findings reinforce the reliability of advanced machine learning techniques in predicting pile bearing capacity on rock.

The present research work demonstrates the effectiveness of data-driven methodologies in predicting the bearing capacity of piles on rock, aligning with and expanding upon the findings in the reviewed literature. Previous studies, such as those by Shahin20, Alkroosh and Nikraz21, and Zhang et al.22, established the potential of machine learning models, including artificial neural networks (ANNs), support vector machines (SVMs), and ensemble learning approaches, in geotechnical predictions. These studies highlighted the superior accuracy of ML models compared to empirical and analytical methods, particularly in capturing complex pile-rock interactions and reducing uncertainties associated with variability in rock properties36,37. The present research confirms these advantages by applying multiple ML models to a comprehensive dataset and assessing their predictive performance. Similar to the findings of Zhang et al.22, who demonstrated the accuracy and reliability of ensemble learning models, this study also validates the effectiveness of different machine learning techniques, showing high R² values across training and validation datasets. Compared to conventional methods, such as those proposed by Rowe and Armitage14 and Kulhawy and Goodman15, which rely on empirical correlations and theoretical assumptions, the ML-based models in the present research achieve significantly improved prediction accuracy, reducing dependence on costly and time-consuming in-situ testing. Additionally, while Zhang and Xu19 introduced a hybrid approach that combined analytical and data-driven methods for enhanced interpretability and accuracy, the present research builds upon this concept by validating ML models using real-world case studies, demonstrating their robustness and practical applicability. Studies such as Park et al.24 and Fattah et al.25 showed that ML models can achieve prediction accuracies exceeding 90%, which is consistent with the present research findings, confirming that advanced ML techniques can provide reliable estimations of pile bearing capacity with reduced computational and experimental effort38,39. Overall, while the reviewed literature established the potential of machine learning in geotechnical applications, the present research extends these findings by systematically comparing multiple ML models, validating their effectiveness, and demonstrating their superiority over traditional methods. This work not only corroborates previous studies but also advances the field by providing a more comprehensive evaluation of data-driven approaches for pile capacity prediction.

Sensitivity analyses

Figures 16 and 17 show the sensitivity analyses with respect to Pu. The sensitivity analysis results from Hoffman and Gardener’s method and SHAP analysis reveal significant insights into the key factors influencing pile bearing capacity on rock. In Hoffman and Gardener’s analysis, Pe (13%), SPTs (13%), and SPTt (13%) are identified as the most influential parameters, followed closely by DSE2 (12%) and DSE3 (12%) (see Fig. 16). These results highlight that penetration resistance, soil strength indices, and dynamic soil parameters play a crucial role in determining pile capacity. In contrast, SHAP sensitivity analysis indicates a stronger dominance of Pe (0.24), SPTs (0.19), and SPTt (0.13) in driving model predictions. Interestingly, while DSE2 maintains its importance (0.12), DSE3 is negligible (0.00), suggesting that its contribution in a data-driven setting is not as impactful as in the traditional sensitivity analysis (see Fig. 17). Both methods agree on the significance of penetration resistance and standard penetration test values, reinforcing their critical role in estimating pile capacity. However, discrepancies between the methods indicate that while empirical sensitivity analysis attributes more weight to broader soil dynamic properties, SHAP highlights the direct influence of specific geotechnical features on model predictions.

Conclusions

The findings of this research highlight the effectiveness of advanced data-driven frameworks in predicting the bearing capacity of piles on rock with improved accuracy and reliability compared to traditional empirical and analytical approaches. The application of machine learning models demonstrates their ability to capture complex interactions between geotechnical parameters, thereby addressing the limitations of conventional methods that rely on simplified assumptions and site-specific data. The following are the important remarks;

-

The performance evaluation of multiple machine learning models, including XNV and DT, reveals that these models exhibit high predictive accuracy in both training and validation phases. The best-fit plots indicate a strong correlation between experimental and predicted values, with determination coefficients (R²) of 0.93 for XNV in training and 0.91 in validation, while DT achieves R² values of 0.94 and 0.91, respectively. These results confirm that the models effectively generalize to new data while minimizing prediction errors, making them viable alternatives to conventional pile capacity estimation methods.

-

The Taylor charts further validate the robustness of the proposed models, demonstrating their strong correlation with measured values and relatively low RMSE values. The comparative analysis shows that the models achieve a balance between bias and variance, ensuring reliable predictions across different datasets. The distribution of standard deviation and correlation coefficients highlights that XNV and DT models maintain stable predictive performance, reinforcing their applicability in geotechnical engineering.

-

Sensitivity analysis using Hoffman and Gardener’s method and SHAP values provides crucial insights into the most influential factors affecting pile bearing capacity on rock. Both methods identify penetration resistance (Pe), standard penetration test values (SPTs, SPTt), and dynamic soil parameters (DSE2) as the dominant factors governing pile behavior. While Hoffman and Gardener’s analysis attributes significant weight to broader soil dynamic properties, SHAP analysis underscores the direct impact of penetration resistance and SPT values in driving model predictions. This dual approach enhances the interpretability of machine learning models and ensures that the identified parameters align with geotechnical engineering principles.

-

A comparison with existing literature further validates the advantages of data-driven approaches. Traditional methods, as reviewed in previous studies, often suffer from oversimplified assumptions, high variability in rock properties, and expensive field-testing requirements. The incorporation of machine learning into pile capacity prediction effectively addresses these challenges by leveraging large datasets, optimizing feature selection, and improving prediction efficiency. Studies by Zhang et al.22, Goh et al.23, and Alkroosh and Nikraz21 have demonstrated the superiority of machine learning techniques over conventional methods, aligning with the findings of this research.

-

Overall, the research confirms that developing an advanced data-driven framework significantly enhances the precision, efficiency, and reliability of pile bearing capacity predictions. The proposed models not only outperform conventional methods but also provide a scalable and cost-effective solution for large-scale geotechnical applications. By integrating sensitivity analysis and robust validation techniques, this study ensures that machine learning-based approaches remain interpretable and practically viable for engineering professionals. Future research should focus on further refining these models by incorporating real-time monitoring data and hybridizing data-driven techniques with physical-based analytical models to enhance their predictive capabilities.

Practical application of research

The practical application of this research lies in its ability to enhance the efficiency, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness of predicting the bearing capacity of piles on rock in geotechnical engineering. By leveraging advanced data-driven frameworks, engineers and construction professionals can make more informed design decisions, reducing reliance on costly and time-consuming field testing methods. The developed machine learning models provide a reliable alternative to traditional empirical and analytical approaches, enabling faster and more precise evaluations of pile capacity. This is particularly beneficial for large-scale infrastructure projects, such as bridges, high-rise buildings, and offshore structures, where accurate foundation design is critical for structural stability. By incorporating real-time site investigation data, these models can be continuously updated and refined, ensuring adaptability to different geological conditions. Another significant application is the optimization of foundation design, leading to material savings and improved safety margins. The sensitivity analysis results highlight key influencing factors, allowing engineers to prioritize critical geotechnical parameters during site assessments. This targeted approach helps in minimizing design uncertainties and enhances the overall efficiency of foundation engineering. Additionally, integrating these predictive models into geotechnical software and automated decision-making systems can streamline the planning and approval processes for construction projects. Governments, engineering firms, and contractors can utilize these models to conduct preliminary assessments, reducing project delays and enhancing regulatory compliance. In disaster-prone regions or areas with highly variable rock formations, the ability to quickly and accurately estimate pile capacity ensures resilient infrastructure development. This research lays the foundation for future advancements in AI-driven geotechnical engineering, potentially incorporating real-time sensor data and hybrid modeling techniques to further refine predictions and optimize construction practices.

Recommendation for future research

Future research should focus on refining the accuracy and generalizability of data-driven models by incorporating larger and more diverse datasets that capture a wider range of geological conditions and pile design parameters. The integration of real-time monitoring systems, such as Internet of Things (IoT) sensors and remote sensing technologies, can enhance model adaptability and predictive performance by providing continuous updates on site conditions. Further investigation into hybrid modeling approaches that combine traditional analytical methods with machine learning techniques can improve interpretability and reliability, ensuring that the models align with established engineering principles. The exploration of deep learning techniques, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), may lead to more advanced feature extraction capabilities, allowing the models to better capture complex pile-rock interactions. Additionally, explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) methods should be incorporated to enhance the transparency of predictions, enabling engineers to understand the reasoning behind model outputs. Cross-validation with extensive field load test data from diverse geographical locations can further strengthen the robustness of the developed framework. Future studies should also assess the environmental and economic implications of AI-driven pile capacity predictions, ensuring their practical feasibility in real-world construction projects. Collaborative efforts between academia, industry, and regulatory bodies will be crucial in establishing standardized methodologies for implementing AI in geotechnical engineering.

Data availability

The data supporting this research work will be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Ji, Y. Estimation of pile-bearing capacity of rocks via reliable hybridization techniques. Multiscale Multidiscip Model. Exp. Des. 8, 103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41939-024-00674-2 (2025).

Hisham, A. et al. Predicting the behaviour of laterally loaded flexible free head pile in layered soil using different AI (EPR, ANN and GP) techniques, Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41939-021-00114-5

Dina, M., Ors, A. M., Ebid, H. A. & Mahdi Evaluating the lateral subgrade reaction of soil using horizontal pile load test results, Ain Shams Engineering Journal 13 (2022). (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2022.101734

Ebid, A. M., Deifalla, A. F. & Onyelowe, K. C. Data utilization and partitioning for machine learning applications in civil engineering. In International Conference on Advanced Technologies for Humanity (pp. 87–100). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-70992-0_8

Ahmed Ebid 35 Years of (AI) in geotechnical engineering: state of the Art. Geotech. Geol. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-020-01536-7 (2020).

Guo, S., Zhang, Y., Iraji, A., Gharavi, H. & Deifalla, A. F. Assessment of rock Geomechanical properties and Estimation of wave velocities. Acta Geophys. 71 (2), 649–670 (2023).

Yago Ferreira Gomes Filipe Alves Neto Verri Dimas Betioli Ribeiro. Use of Machine Learning Techniques for Predicting The Bearing Capacity of Piles. Soils and Rocks, Volume 44, N. 4. (2021). https://doi.org/10.28927/SR.2021.074921

Millán, M. A., Picardo, A. & Galindo, R. Application of artificial neural networks for predicting the bearing capacity of the tip of a pile embedded in a rock mass. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 124 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106568 (2023).

Kumar, M. et al. Prediction of bearing capacity of pile foundation using deep learning approaches. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 18, 870–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11709-024-1085-z (2024).

Benbouras, M. A., Petrişor, A. I., Zedira, H., Ghelani, L. & Lefilef, L. Forecasting the bearing capacity of the driven piles using advanced Machine-Learning techniques. Appl. Sci. 11 (22), 10908. https://doi.org/10.3390/app112210908 (2021).

Deng Yousheng, Z. et al. Machine learning based prediction model for the pile bearing capacity of saline soils in cold regions, structures, 59, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105735

Khatti, J., Khanmohammadi, M. & Fissha, Y. Prediction of time-dependent bearing capacity of concrete pile in cohesive soil using optimized relevance vector machine and long short-term memory models. Sci. Rep. 14, 32047. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83784-8 (2024).

Amjad, M. et al. Prediction of pile bearing capacity using XGBoost algorithm: modeling and performance evaluation. Appl. Sci. 12 (4), 2126. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12042126 (2022).

Rowe, R. K. & Armitage, H. H. A design method for drilled piers in soft rock. Can. Geotech. J. 24 (1), 126–142 (1987).

Kulhawy, F. H. & Goodman, R. E. Design of foundations on discontinuous rock. Proceedings of the International Conference on Structural Foundations on Rock, Sydney, Australia, 209–220. (1980).

Pells, P. J. N. The design of piles socketed into rock. Australian Geomech. J. 52 (4), 1–20 (2017).

Zhang, L. & Einstein, H. H. End bearing capacity of drilled shafts in rock. J. Geotech. GeoEnviron. Eng. 124 (7), 574–584 (1998).

Hoek, E. & Brown, E. T. Practical estimates of rock mass strength. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 34 (8), 1165–1186 (1997).

Zhang, L. & Xu, Y. Machine learning in geotechnical engineering: A review. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 37 (3), 1221–1245 (2019).

Shahin, M. A. Load-settlement modeling of axially loaded steel driven piles using CPT-based recurrent neural networks. Soils Found. 54 (3), 515–522 (2014).

Alkroosh, I. & Nikraz, H. Predicting pile capacity using support vector machines and random forests. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 6 (4), 341–349 (2014).

Zhang, W., Zhang, Y. & Goh, A. T. C. Predicting the bearing capacity of rock-socketed piles using ensemble learning techniques. Comput. Geotech. 117, 103261 (2020).

Goh, A. T. C., Zhang, W. G. & Zhang, Y. M. Ultimate load capacity prediction of piles using neural networks. Geotech. Eng. 36 (1), 123–128 (2005).

Park, D., Kim, S. & Lee, J. Evaluation of machine learning models for pile bearing capacity prediction. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 125, 105723 (2019).

Fattah, M. Y., Al-Mufty, A. & Salman, K. Application of machine learning techniques in pile capacity prediction. J. Geotech. Eng. 147 (3), 04021021 (2021).

Ebid, A. E., Deifalla, A. F. & Onyelowe, K. C. Data utilization and partitioning for machine learning applications in civil engineering. In International Conference on Advanced Technologies for Humanity (pp. 87–100). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. (2023)., December https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-70992-0_8

Hoang, N. D. & Thanh-Canh, T. X. L. H. Prediction of Pile Bearing Capacity Using Opposition-Based Differential Flower Pollination-Optimized Least Squares Support Vector Regression (ODFP-LSSVR), Advances in Civil Engineering, 7183700, 25 pages, 2022. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7183700

Binh Thai, P. et al. Estimation of load-bearing capacity of bored piles using machine learning models. Vietnam J. Earth Sci. 44 (4), 470–480. https://doi.org/10.15625/2615-9783/17177 (2022).

Gu, W., Liao, J. & Cheng, S. Bearing capacity prediction of the concrete pile using tunned ANFIS system. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 71, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-024-00369-y (2024).

Lai, V. Q. et al. A machine learning regression approach for predicting the bearing capacity of a strip footing on rock mass under inclined and eccentric load. Front. Built Environ. 8, 962331. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2022.962331 (2022).

Shahin, M. A. Intelligent computing for modeling axial capacity of pile foundations. Can. Geotech. J. 47 (2). https://doi.org/10.1139/T09-094 (2010).

Sofia Leão Carvalho, Mauricio Martines Sales and André Luís Brasil Cavalcante. Systematic literature review and mapping of the prediction of pile capacities. Soils Rocks. 46 (3). https://doi.org/10.28927/SR.2023.011922 (2023).

Hoffman, F. O. & Gardner, R. H. Evaluation of Uncertainties in Radiological Assessment Models. Chapter 11 of Radiological Assessment: A textbook on Environmental Dose Analysis. Edited by Till, J. E. and Meyer, H. R. NRC Office of Nuclear Reactor Regulation, Washington, D. C. (1983).

Yazan & Alomari Mátyás Andó, SHAP-based insights for aerospace PHM: Temporal feature importance, dependencies, robustness, and interaction analysis. Results Eng. 21 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101834 (2024).

Nourkojouri, H., Shafavi, N. S., Tahsildoost, M. & Zomorodian, Z. S. Development of a Machine-Learning framework for overall daylight and visual comfort assessment in early design stages. J. Daylighting. 8, 270–283. https://doi.org/10.15627/jd.2021.21 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. A physics-informed machine learning solution for landslide susceptibility mapping based on three-dimensional slope stability evaluation. J. Cent. South. Univ. 31, 3838–3853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-024-5687-3 (2024).

Songlin Liu, L. et al. Physics-informed optimization for a data-driven approach in landslide susceptibility evaluation. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16, Issue 8,, 3192–3205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2023.11.039 (2024).

Po Cheng, Y., Liu, Y. P., Li, J. & Yi, T. A large deformation finite element analysis of uplift behaviour for helical anchor in spatially variable clay, computers and geotechnics, 141, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2021.104542

Po Cheng, F., Liu, X., Chen, Y., Zhang, K. & Yao Estimation of the installation torque–capacity correlation of helical pile considering spatially variable clays. Can. Geotech. J., 61, Issue 10, 2024, Pages 2064–2074, https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2023-0331

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Funding

The authors received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions