Abstract

Owing to the proliferation of mobile devices, Google’s Android operating system has become a dominant force in global communication. However, its popularity makes it a prime target for cyberattacks. Effective malware detection systems are crucial for combating these escalating threats, particularly amid the evolving use of adversarial examples to evade detection. These systems employ static and dynamic analysis methodologies with machine learning, particularly Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which play a key role. The Android Opcode Modification GAN enhances malware detection by intelligently modifying opcode distribution features using the Opcode Frequency Optimal Adjustment algorithm. Despite its effectiveness, the dual-opponent generative adversarial network (DOpGAN) introduces a grey-box attack strategy that misclassifies generated examples as benign, significantly evading detection. DOpGAN operates by altering opcode distribution features during the generation and insertion process, making it particularly challenging for detection systems to classify correctly. The adversarial examples generated by DOpGAN highlight the critical need to integrate defensive measures such as adversarial example detection systems into the Android security framework. Beyond evasion, these adversarial examples provide invaluable opportunities for retraining and improving malware detection systems, thereby ensuring their resilience against emerging threats. The findings underscore the broader need for continuous innovation in Android security mechanisms, fostering collaboration between academia and industry to protect users and systems in an ever-evolving mobile security landscape.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pervasive use of handheld devices establishes them as the primary global communication medium, emphasizing the importance of the Android operating system (OS) as the leading OS1. However, this popularity also makes Android a prime target for cyber-attacks, with various mobile security breaches impacting the operating system2. As threats increase, the security of the Android operating system becomes predominant3. Highly effective malware detection systems are typically used to strengthen security infrastructure4. As cyber threats become increasingly sophisticated, these systems are playing a critical role in determining the nature of potentially malicious applications.

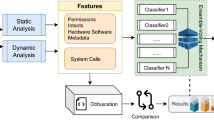

Recent developments have revealed a trend where adversarial examples are strategically used to deceive Android malware detectors5 highlighting the need for advanced security measures. The framework for analyzing and addressing these threats is generally divided into two main approaches: static analysis6 and dynamic analysis7. A static analysis examines the code without running it, making it possible to evaluate whether it is safe or harmful. Conversely, dynamic analysis requires running the code in a protected environment, which facilitates consideration of its behavior in real time to make well-informed judgments.

Adversarial examples, characterized by their adeptness in evading handheld security systems, pose formidable challenges for traditional detection methods8 regarding accuracy and efficiency. In response to these challenges, machine learning methods9 have gained prominence, with Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) emerging as powerful tools. Proposed by Goodfellow in 201410, GAN excels in learning the distribution of target datasets, presenting the potential to generate adversarial features for Android Application Packages (APK). Despite these advancements, the susceptibility of high-level feature modifications to detection using feature-based detectors underscores the need for continuous innovation. In this context, Android Opcode Modification GAN (AndrOpGAN)11 was introduced to execute evasion attacks by intelligently modifying the statistical distributions of opcode features. This approach builds upon the foundation of DCGAN, originally designed for image generation, to enhance the meaningful generation of opcode distributions.

Additionally, to ensure accuracy in both syntax and meaning when altering features, the proposal includes an Opcode Frequency Optimal Adjustment (OFOA) algorithm module. This module adds a layer of sophistication to the malware detection framework, enhancing the system’s ability to distinguish between benign and malicious codes. Although AndrOpGAN exhibits high efficacy in evading opcode distribution-based detectors, its vulnerability to detectors, especially those capable of capturing adversarial examples, raises concerns about its effectiveness. A large number of examples created by AndroOpGAN were stopped by the detection system equipped with an adversarial example detector. To address this limitation, a dual-opponent generative adversarial network (DOpGAN) has been presented. DOpGAN uses a generator and two discriminators simultaneously to deceive both adversarial example detectors and traditional malware detectors, thereby significantly enhancing its evasion capabilities. The complex realm of mobile device security requires ongoing innovation to remain ahead of the constantly changing cyber threats. The convergence of machine learning, specifically through Generative Adversarial Networks, exemplifies the dynamic nature of the security measures employed in the Android ecosystem. The juxtaposition of static and dynamic analyses, combined with the sophistication of adversarial examples and the resilience of advanced detection mechanisms, provides a comprehensive picture of the ongoing battle to safeguard the Android operating system against malicious intrusions. Moreover, existing Android malware detection techniques, including ML-based models, remain vulnerable to GAN-generated adversarial malware, which systematically alters the opcode distributions to evade detection. However, prior research lacks a detailed investigation of opcode-level adversarial modifications, their evasion success rates, and their impact on real-world detection systems. Additionally, existing works primarily focus on the image and text domains, with limited exploration of GAN-driven evasion in Android security. To bridge this gap, our study presents a novel opcode-based adversarial attack framework that systematically evaluates its effectiveness against ML-based detection, and proposes mitigation strategies. However, this study focuses on developing a robust framework for generating synthetic malware through Generative Adversarial Networks. The goal is to craft malware variations capable of bypassing current machine learning detection models for Android malware and enduring the analysis of conventional Android Firewalls. This study makes several noteworthy contributions including the following:

-

The generated malware must be executable, and any modifications introduced in Android malware applications for evasion should not compromise the original attack.

-

Develop a Duel Objective GAN model for operation code distribution obfuscation, targeting evasion of Android malware detection systems and adversarial example detector.

-

The resulting malware variants produced through GANs should possess the capability to circumvent multi-feature ML models utilized in malware detection, including features related to the operation codes.

The remainder of this paper is organized into five sections. Section “Related work” I discusses related work on malware detection. Section “Proposed framework for evasive adversarial attack against android malware defense” presents the proposed framework for evasive adversarial attacks against Android malware. Section “Analysis and results” highlights the results and discussion. It also includes a performance comparison of the proposed GEAAD. The final section presents our conclusions.

Related work

In this ever-evolving technological landscape, dedicated organisations work continuously to strengthen cyberattack defence while parallel to them just as dynamic and powerful malicious threat actors - advanced attackers. Cybersecurity professionals are constantly evolving their countermeasures while adversaries mimic and work to circumvent them. The continued arms race between protectors and attackers is how sophisticated cyber threats have become in the digital world. The quest for successful cyberattack prevention strategies has fuelled the invention and implementation of advanced technologies. Attackers are creative as they consistently evolve and develop new ways to modify their methods, whereas lots of the regular security mechanisms seem unable to keep up. The stakes of this arms race mean that cybersecurity policymaking needs to constantly evolve and be agile in looking for new vectors of attacks. This adversarial learning includes the implementation of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) IE; an example of that by an adversary.

Evasion attacks may not be as effective in the Android domain as they have been in the Windows domain because their manipulations may not be suitable for changing Android malware programs in a way that can fool current Android malware detectors. To predict potential evasion attacks, numerous research have been conducted in the past few years to produce AEs in the Android environment. The threat models that the researchers took into consideration are shown in Table 1. It should be noted that when classifying studies under the ZK setting, adversaries should not only be unable to access the specifics of the target model, but also not have any preconceived notions about it (such as the kinds of features that detectors use). Like, Croce et al.12 presented Sparse-RS, a query-based attack that produced AEs through a random search technique, to investigate feature-space AEs. Reinforcement learning was used by Rathore et al.13 to create AEs that tricked Android malware scanners. To assess their protection tactics, Chen et al.14 used several feature-based attacks, such as brute-force attacks. A white-box attack was provided by Demontis et al.15 to disrupt Android malware app feature vectors with respect to the key aspects that influence malware classification. Further, to improve ML-based malware detectors, Liu et al.16 presented an automated testing framework built on a Genetic Algorithm (GA). Based on the simulated annealing process, Xu et al.17 suggested a semi-black-box attack that modifies Android app features. Since they don’t demonstrate how real-world applications may be recreated using feature-space perturbations, the aforementioned attacks appear to be unfeasible18.

Besides, Grosse et al.19 altered the Android Manifest files according to the feature-space perturbations in order to study problem-space manipulations. A similar strategy was employed by Berger et al.20; however,18 considered both Dalvik bytecodes and Manifest files of Android apps in their techniques of modification. To produce AEs utilizing a substitution model based on permissions and API call features, Zhang et al.16 presented an adversarial assault named ShadowDroid. Next, GenDroid, a query-based attack that used GA by including an evolutionary strategy based on Gaussian Process Regression, was first presented by18. Because the generated AEs may not meet all of the conditions in the issue space (e.g., plausibility and robustness to preprocessing) the viability of these attacks is therefore called into question. For example, found that five of ten validated modified apps were unable to function properly.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANS), which were originally crafted for the better good in the field of machine learning have been twisted and turned by malefic developers to break various constructs of cybersecurity.

These sophisticated algorithms are incredibly efficient at generating lifelike copies of data, enabling malicious actors to produce falsified content which can bypass traditional security mechanisms. The perpetrators use GANs in attacks, showing the potential to exploit advanced technologies made to improve cyber security. The nature of this phenomenon, collision between technology and cyber dangers, also demands a thorough multi-disciplinary conversation between Computer Science, Ethics and Policy researchers to elucidate the extent of challenges that come into play. Static and dynamic analysis: As mentioned in the first part, static and dynamic analysis are 2 most common used methodologies to detect Android malware.

Android, based on Linux, is an open-source operating system that can lead to a favourable gesture for making it an everyday smartphone, which abounds in markets today. Therefore, the surge in the use of Android-based smartphones has made them a suitable and tempting target for malware distributors and prompt mechanisms are required which can perform fast detection of Android malware. A new method for Android malware detection is the genetic algorithm (GA) used in this study to select the features21. This study evaluates the performance of three different classifier algorithms, using feature subsets detected by the GA to detect and analyse Android malware. Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Genetic Algorithms (GA), when used together with a selected set of 16 permissions, had the highest accuracy of 98.45%. The research study had a dataset of 1740 samples with 1119 malware samples and 621 non-malicious ones. The increasing prevalence of Android malware necessitates efficient analysis methods22. Familial analysis, which identifies commonalities within malware families, is promising but suffers from limitations such as low accuracy, inefficiency, and dependence on labelled data. To address these issues, this paper introduces SRA, an innovative characteristic that captures analogy relationships between “Framework Tasks” of reactive API calls within subgraphs. This transformation simplifies the complex graph matching into a faster, vector-based similarity calculation. GefDroid employs unsupervised learning techniques to analyse malware families. It builds a network of malware connections using SRAs and applies community detection algorithms to categorise unlabelled specimens. GefDroid outperforms existing approaches in accuracy and efficiency, achieving high agreement with ground truth across various datasets (0.707–0.883 NMI). Additionally, GefDroid exhibits significant speed improvements, analysing a sample in around 8.6 s on average with minimal runtime overhead. To sum up, SRA successfully identifies similarities, and GefDroid outperforms in malware family analysis on Android platforms through unsupervised learning, marking a notable improvement upon current approaches.

Moreover, this study23 introduces a technique for identifying Android malware using deep learning, leveraging information gathered from instruction call graphs. By ensuring a balanced dataset, this method scrutinises every possible execution route to better differentiate between safe and harmful paths using deep neural networks. With no readily available pre-trained models, we start training networks from the ground up, fine-tuning the parameters through grid search. When tested on an evenly distributed dataset comprising 24,650 malware and 25,000 non-malware samples, this technique reaches an accuracy of 91.42% and an F-measure of 91.91%. It undergoes a comparative evaluation with standard classifiers, analysing various parameters, statistical measures, and execution times. The approach overcomes obstacles found in static and dynamic analysis by introducing a deep learning framework that incorporates convolution over sequences of opcodes.

Recent findings underscore the vulnerability of existing Android malware detection systems to (GAN) based adversarial example attacks. While deploying a firewall as an adversarial example detector has proven effective in countering such threats, a novel bi-objective GAN-based adversarial example attack has emerged as a potent method that breaks through firewall-equipped Android malware detection systems with an impressive success rate exceeding 95%31. This method surpasses the modern approach by a remarkable gap of 247.68%. Integrating a firewall significantly enhances the capture rate of adversarial examples when using an Android malware detection system. However, in response to this, new black-box adversarial attack techniques have been proposed, demonstrating their efficacy as over 95% of its generated adversarial examples evade detection and are falsely classified as benign by the firewall-equipped system. This dynamic landscape underscores the constant interplay between evolving attack strategies and the defensive measures implemented in cybersecurity.

This paper presents an innovative architecture called Attack Inspired Generative Adversarial Network (AI-GAN)32, designed to mitigate the vulnerability of Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) to adversarial examples that intentionally alter inputs, resulting in erroneous model predictions. Notwithstanding comprehensive research on many attack strategies, creating nuanced yet potent adversarial samples is a challenging problem. The AI-GAN combines a generator, discriminator, and attacker into a cohesive training framework, facilitating the generation of adversarial alterations customized for various images and categories. AIGAN has shown its capacity to achieve high effectiveness rates and significantly reduce generation time by testing benchmarks such as MNIST and CIFAR-10 compared to earlier methods. Notably, it maintains its efficacy with more complex datasets such as CIFAR-100, attaining an approximate success rate of 90% across several categories. AI-GAN takes all three basic components and trains them concurrently, thereby speeding up the malicious example-creation process and providing better operational efficiency while still maintaining picture fidelity. AI-GAN offers better performance than prior methods in most circumstances evaluated to date, including scenarios with defenses and natural white-box settings. The new paradigm and objectives in training AI-GAN represent significant progress in solving the problem caused by friendly fire adversarial examples in deep neural networks.

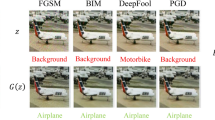

A recent study also highlighted the vulnerability of deep-learning models used in Synthetic Aperture Radar Automatic Target Recognition (SAR-ATR) to adversarial example attacks. These manipulated inputs introduce misclassification in Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) systems by introducing minor perturbations in SAR images. State-of-the-art optimization-based attacks minimize reconstruction errors using soft adversarial examples with weak, blurred scatters, and softened target edges. We propose an architecture that pairs a UNet with a small Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to produce more potent adversarial examples for Synthetic Aperture Radar automatic target recognition (SAR-ATR) systems. The UNet model is employed for feature separation and adversarial sample generation. The GAN module ensures that they are similar to authentic SAR imaging with clear edges and strong weak scattering, which contributes to its effectiveness. Testing has shown this to work for defeating capable Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based SAR-ATR systems on real ground-vehicle SAR datasets. Attack-UNet-GAN generated adversarial instances that appeared as normal images but were misclassified by a pre-trained CNN. Thereby, the non-human-like attack signal is embedded into an image while maintaining the introduced human similarity modifications without requiring further iterative optimization changes. A discriminator in the architecture ensures that adversarial samples respect pertinent SAR image features and thus enhance their deceiving capability, as they make them conducive to highlighting the target edge and weak scattering centers. Future research can examine black-box attack methods in practical scenarios where there is no information regarding the unknown SAR-ATR model distribution. Such a study may help form a universal attack method33 if the transferability of adversarial cases can be studied among SAR-ATR models from different companies. The emergence of machine learning in malware detection has initiated cat-and-mouse dynamics, with attackers continuously devising strategies to circumvent these advancing algorithms. Confronted with the obstacles presented by the impenetrable characteristics of machine-learning models in malware detection, attackers frequently employ black-box tactics to compromise these systems21. This paper presents MalGAN, a novel method that employs a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to generate adversarial malware samples that evade detection using black-box machine learning methods. MalGAN uses a surrogate detector to replicate the behavior of the target system, whereas its generative component is trained to minimize the probability of its samples being identified as malicious.

Furthermore, the rapid advancement of adversarial machine learning has spurred the development of various attack methods that traditionally rely on neighborhood searches of images to create adversarial samples28. Since 2017, generative models have been integrated into these attacks, typically focusing on creating adversarial perturbations from the input noise or an initial image. However, these approaches limit the output to resemble the initial input closely. This paper proposes Adversarial Transfer on Generative Adversarial Net (AT-GAN), a novel generation-based attack method. AT-GAN trains a generative model capable of producing diverse and realistic adversarial examples from the input noise. This avoids the limitations of previous approaches in which the output is constrained by the initial input. Tests reveal that the AT-GAN outperforms attacking models trained to resist such threats, highlighting its superior effectiveness and efficiency. Notably, our findings suggest that adversarial training, a common defense method based on a perturbation-based adversarial sample, might not ensure robustness against a non-constrained adversarial sample because of the broader diversity captured by AT-GAN in adversarial sample distribution deep neural networks19. They are susceptible to adversarial examples created by adding small perturbations to the inputs, leading to misleading results. Despite the various proposed attack strategies, achieving high-quality and efficient adversarial examples remains a challenge. This study introduces AdvGAN, which determines a GAN to create adversarial examples by learning the underlying characteristics of real data. Once trained, the AdvGAN generator efficiently produces perturbations for any instance, potentially accelerating adversarial training as a defense. AdvGAN demonstrates effectiveness in semi-white-box and black-box attack contexts, delivering superior performance against leading defense mechanisms compared to alternate strategies. Significantly, AdvGAN achieved the highest rank by securing a 92.76% success rate in a widely recognized MNIST black-box attack competition. This achievement underscores AdvGAN’s potential as a valuable tool for enhancing defence strategies through adversarial training, showcasing its ability to craft adversarial examples efficiently across various attack scenarios.

In addition, the adversarial weakness of DNNs has been widely studied in image classification models; however, little attention has been paid to its effect on image retrieval, as shown in Table 1. In this study, we propose a new approach to fooling deep neural network DNN-based image search engines using Unsupervised Adversarial Attacks with Generative Adversarial Networks (UAA-GAN). Unlike traditional techniques, UAA-GAN is effective in unsupervised learning, requiring only a portion of the data to generate attacks. However, it is centered on the generation of query-specific perturbations that lightly modify the input images to produce their adversarial counterparts. The encoded modifications aim at effects that are barely noticeable to the human viewer but remove certain positions of the image in the deep feature space, thereby failing a retrieval system that relies heavily on this positional information. Diverse applications using deep learning features that can witness UAA-GAN are based on image search, person re-identification (Re-ID), and facial recognition tasks. Experiments show that UAAGAN can disrupt typical queries with no apparent alteration to an image. These generated adversarial images are designed to introduce minimal noise by blending pixels with high information content or intrinsic image characteristics (e.g., body parts or major patterns) regardless of where the area is located on an image, which ensures that a texture-rich background can produce a higher difference between them and their clean versions. This tactic is deceiving in image retrieval algorithms as the original appearance of the image also remains intact, showing that UAA-GANs have the potential to deal with both objectiveness and subjectiveness between machine perception and human vision. In this study, we comprehensively evaluate the UAA-GAN method over multiple tasks and datasets, which demonstrates the effectiveness of UAA-GAN, revealing its adversarial attack abilities and generalisability to different target models.

Moreover, the increasing sophistication of malware has led to significant advancements in adversarial machine learning (AML), particularly in the domain of Android malware detection. Goodfellow et al.34 first introduced adversarial machine learning, highlighting how neural networks can be easily fooled by crafted perturbations. Following this, Papernot et al.35 demonstrated black-box adversarial attacks on deep learning models, emphasizing the vulnerabilities of security-critical applications. Specifically, adversarial learning has been applied in malware detection, with Hu and Tan36 introducing MalGAN, one of the first GAN-based adversarial malware generation models, which successfully bypassed traditional classifiers by modifying feature representations. However, MalGAN operates in a black-box setting, limiting its ability to learn feature-level modifications dynamically. To address this, Carlini and Wagner37 proposed stronger adversarial attacks for cybersecurity systems, influencing the evolution of malware evasion techniques.

More recently, research has expanded to GAN-based adversarial attacks targeting Android malware detectors. Li et al. introduced AdvGAN, a white-box adversarial malware generation framework that optimizes perturbation generation for evading detection models38. However, AdvGAN lacks adaptability when detectors integrate adversarial training. They proposed a dual-optimization approach to improve evasion rates, but their model is ineffective against adversarial example detectors38. Unlike previous approaches, DOpGAN introduces a grey-box learning framework that dynamically modifies opcode distributions while adapting to adversarial detectors, making it significantly more effective in malware evasion.

Proposed framework for evasive adversarial attack against android malware defense

In this study, we focused on dynamic malware analysis, in which applications are executed within controlled environments such as virtual machines and sandboxes to prevent damage to actual machines, in contrast to static analysis, which uses application features for quick and cost-effective malicious behavior identification. Notably, static analysis via machine learning is prone to evasion, particularly by synthetic malware variants generated using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). AndrOpGAN, employing a Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN), effectively crafts adversarial examples to bypass various classifiers, such as SVM, K-NN, and CNN, dramatically reducing their detection rates. However, its efficiency decreases in firewall-equipped systems that detect adversarial input. To enhance evasion capabilities, we introduced DOpGAN, a dual-objective GAN designed to circumvent malware detection systems and firewalls simultaneously, marking a pioneering effort in advanced evasion techniques against Android security frameworks with firewall integration.

DOpGAN

DOpGAN operates as a grey-box model, meaning it can infer the type of features used in the detection system by interacting with it. As shown in Fig. 1, the framework consists of two key components.

Grey-box model

The dual-opponent generative adversarial network (DOpGAN) infers the features used by target malware detection systems using a grey-box model. The attacker in a gray-box attack does not have complete access to the system’s core architecture, but they do have some understanding of its function, such as feature selection or learning methods. By communicating with the target system to learn about the opcode distribution characteristics, DOpGAN takes advantage of this incomplete knowledge and optimizes adversarial samples for escape. The discriminator components of the DOpGAN, which are used in the feature inference process, can learn the decision boundaries of the detection system. The generator generates hostile samples during training, which are intended to be mistakenly identified as benign by adversarial example detection systems and malware detectors. This iterative procedure aids DOpGAN in deducing the decision-making criteria of the detection system by modifying the opcode distributions in response to the discriminator feedback.

Operation code frequency feature

The Dalvik instruction set encompasses over 200 types of opcodes, yet numerous instructions exhibit similarities. To streamline feature space dimensions for enhanced efficiency in detection, similar opcodes were grouped into identical classes, resulting in a total of 44 classes in our study39, without consideration for data types and register distinctions. Table 2 provides a listing of some opcode classes.

The opcode set A consists of 44 elements \(\{a_1, a_2, a_3, \dots , a_{44}\}\), representing different types of opcodes for each Android software sample x. The function \(\phi (x)\) computes a vector representing the normalized count of each opcode type. The numerator of \(\phi (x)\) counts the occurrences of each opcode a in A within sample x. The denominator sums the counts of all opcodes a in A for sample x, normalizing the counts. This leads to a vector with 44 dimensions, each representing a unique opcode type, with their counts normalized. The function \(\phi (x)\) maps x to a 44-dimensional vector.

Each \(a_i\) dimension in the resulting vector represents a specific opcode type from the opcode set A. The numerator of \(\phi (x)\) counts the occurrences of each opcode type a in the opcode set A within sample x. The denominator sums the counts of all opcodes a in the opcode set A for sample x, resulting in normalized counts. The ratio is calculated as

Normalization ensures that the vector represents relative frequencies of opcode types rather than absolute counts.

Operation code distribution feature generation

The module responsible for generating opcode distribution features was developed using a modified DCGAN. This adapted version of DCGAN uses random noise as its input and output features that mimic the distribution of benign opcode characteristics.

Parameters for discriminator

It is very important to optimize when creating the discriminator for outputting opcode distribution features around a variety of key details and things to consider, so let us improve this aspect as well. The input layer is set up to match the opcode distribution feature dimensionality with opcode sequences represented as N-long vectors. Therefore, the discriminator input dimension is simply the vector length that conforms to the sequence representation.

The architecture starts with Convolutional Layers, which are necessary for obtaining the spatial hierarchies present in the opcode sequences. The layers detect patterns of the opcode distribution; therefore, the number of convolutional layers and the number of filters in each layer are important parameters to be optimized. It is recommended to use different filter sizes to capture different granularities in the opcode sequences so that the model can learn meaningful patterns at multiple scales. The rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation was used at the convolutional layers to learn nonlinear functions and mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, which helps in efficient learning. One method of avoiding problems such as the “dying ReLU” phenomenon is to use the Leaky ReLU in which there is a small, non-zero output for inactive units so that learning can still take place during back-propagation.

Pooling or striding is used to decrease the spatial dimension after the convolutional layers. In particular, max pooling can be used to downsample feature maps, which allows the network to learn hierarchical features better. Not only does pooling significantly reduce the computational complexity, but it also brings our transducer one step closer to being translation-invariant. The discriminator output layer norms a single-node sigmoid. This output node is meant to provide a probability score, quantifying the probability that the input opcode distribution is real (as in real data) and not produced by the generator. The model uses the binary cross-entropy loss function for measuring the distance between the true opcode distribution and predicted distribution so that it would be trained to minimize the prediction error.

Therefore, to make this architecture efficient, we must select an optimizer that can work effectively with these types of architectures. Optimizers: Adaptive optimizers work better; for example, Adam is very popular as it works efficiently with default gradient descent and adapts the learning rate to speed up convergence. Moreover, batch normalization was used after the convolutional layers to normalize each layer input with zero mean and unit variance. The sole purpose of this third step is to stabilize the training process, but it actually has very good side effects: it speeds up learning and enables a deeper network to be simply trained as if it were shallow.

Finally, the convolutional layers are followed by fully connected (dense) layers. The network is further comprised by dense layers that can learn complex relations between the features extracted from the opcode distribution. This allows the network to use information from all over the input sequence because any node can communicate with every other node.

Parameters for generator

Setting up a generator to produce opcode distribution features involves many important decisions and adjustments designed to ensure the network effectively learns the relationship between random noise input and sequences of interest in opcode distribution. Generator input Various random noise taken from a simple distribution (eg Guassian or Uniform) This noise acts as a hidden variable space that the generator will learn to map onto realistic opcode distributions.

The big difference from the vanilla GAN is that the generator has some convolutional layers, which are necessary for the model to learn spatial hierarchy and patterns in opcode sequences. These filters for the different layers are especially important because this is how we can capture one of the most basic things about the distribution of opcodes. Number of layers and filters need to be finely tuned to ensure that the model picks up enough detail from the input noise while also keeping below desired computational complexity.

The selection of activation functions is a crucial factor in the architecture of the generator. ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activations are frequently employed in the convolutional layers of the generator because of their efficacy in training deep networks and their capacity to alleviate the vanishing gradient issue. In the output layer, the Tanh activation function is commonly utilized. The Tanh function scales the output to align with the anticipated range of opcode distribution features, so ensuring that the generated sequences are accurately represented within the relevant feature space.

Batch normalization is implemented across the network to improve training stability and speed. Batch normalization standardizes the input for each layer, mitigating problems such internal covariate shift, which facilitates faster convergence of the network. The generator utilizes upsampling layers or transpose convolutional layers to augment the spatial dimensions of the data. These layers are crucial for producing extended opcode sequences by augmenting the dimensionality of the latent noise input, so converting it into the requisite feature space. This phase is essential for generating high-resolution outputs that mimic authentic opcode distributions.

The generator’s output layer is configured to align with the dimensionality of the opcode distribution features. If each opcode distribution feature is denoted by a vector of length N, the output layer will have N neurons. The application of the Tanh activation function at this juncture guarantees that the produced output is appropriately scaled to the range of actual opcode distribution feature values, facilitating seamless incorporation into the overall model pipeline. The generator’s loss function is the binary cross-entropy loss, which evaluates the efficacy of the generated samples in deceiving the discriminator into categorizing them as authentic opcode distributions. This loss function is essential for directing the generator to enhance the quality of its outputs progressively.

Finally, the Adam optimizer is commonly selected due to its efficiency and adaptive learning rate properties. Its ability to dynamically adjust learning rates during training makes it a robust choice for optimizing the generator, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional and complex data like opcode distributions.

Training process

This segment describes the training and creation processes of AndrOpGAN, illustrated in Fig. 2. Features extracted from benign APKs and malicious APKs first used to train Discriminator 1 and features extracted from adversarial examples and normal examples are used to train Discriminator 2. After that Generator is trained with two discriminators simultaneously Meanwhile, Discriminator 1 is tasked with identifying the difference between benign and malicious instances, and Discriminator 2 focuses on separating adversarial examples from regular ones. Within this GAN framework, the dual role of the discriminators directs the generator towards accomplishing two goals concurrently: bypassing android malware detector and evading recognition by Adversarial example detection frameworks.

Feature extraction tool

AndroGuard is an open-source tool designed to analyse Android applications and extract various features for security analysis, malware detection, and reverse engineering. It is coded in Python and provides comprehensive functionalities to dissect Android apps and extract valuable information. AndroGuard employs a combination of static and dynamic techniques to extract features from APKs. It decompiles the APK file to obtain the AndroidManifest.xml, resources, and DEX bytecode files. AndroGuard’s primary focus is static analysis, which provides limited dynamic analysis capabilities. It can simulate certain aspects of the app’s behaviour, such as intent resolution and method call resolution. This dynamic analysis could help in clarifying the potential behaviour of the app without actually running it on a device. The extraction of opcode features is essential for an analysis of Android applications, especially in evaluating their behaviour and functionality. In this process, tools such as AndroGuard are essential, as they can extract intricate opcode characteristics from Android application packages (APKs), enabling a more thorough examination of a program’s code architecture and functionality. The procedure commences with DEX decompilation, during which AndroGuard decompiles the APK’s DEX bytecode file. The DEX file comprises the executable code for the application, and by transforming this file into a more coherent and alterable format, AndroGuard facilitates a more thorough investigation of the application. This decompilation is crucial as it converts compiled bytecode into a human-readable format, revealing the underlying code instructions.

Feature extraction from the APK samples was carried out using a three-pronged approach to capture various aspects of the applications’ behavior. The first feature category, opcode distribution, involved analyzing the frequency of opcode sequences executed by each application, providing insights into the dynamic behavior of the malware. The second category, API calls, was derived through static analysis to identify the API functions invoked by each application, further revealing its interaction with the underlying system. The third feature category, permission analysis, examined the Android permissions required by each APK, highlighting potential vulnerabilities and suspicious behavior. Feature extraction was performed using AndroGuard and APKTool, ensuring compatibility across different datasets and maintaining consistency in the analysis. This thorough feature extraction methodology contributes to a robust foundation for evaluating DOpGAN’s performance in malware detection.

In addition, an open-source Python program called AndroGuard analyzes Android apps, helps with reverse engineering, and extracts static features that are essential for identifying malware. Decompiling APK files to obtain resources, DEX bytecode files, and AndroidManifest.xml all crucial for feature creation and analysis is one of its primary purposes. Important functions consist of:

-

DEX Decompilation: AndroGuard transforms DEX bytecode files into a format that can be read by humans so that they can be examined further.

-

Opcode Extraction: Opcode instructions, which describe how the application behaves on the Dalvik or ART virtual machines, are extracted by parsing the decompiled DEX file.

-

Feature Generation: To create numerical vectors that serve as input features for the DOpGAN framework, the extracted opcodes are arranged into sequences.

Upon decompiling the DEX file, the subsequent step is opcode extraction. Opcodes, or operational codes, are the fundamental instructions used by the Dalvik or Android Runtime (ART) virtual machines to perform operations within the application. AndroGuard recognises and extracts these opcodes by analysing the decompiled DEX bytecode. This stage is essential for examining the application’s functional components, as the opcodes represent the directives that govern its execution flow. Upon extraction of the opcodes, AndroGuard systematically arranges them into sequences that delineate the application’s execution pathways. These opcode sequences function as significant features applicable for various reasons, such as static analysis, virus detection, and behavioural profiling. Using opcode sequences, researchers and analysts can acquire insights into the underlying operations of the application and detect potential security vulnerabilities or anomalous behaviour patterns.

DCGAN based model structure

In Fig. 3 illustrates that generator uses input in the form of 200-dimensional random noise and is built with convolutional layers, layers for up-sampling, fully connected layers, and processes for reshaping. The output from the generator is a 44-dimensional feature vector, with each dimension representing the occurrence frequency of a distinct opcode category.

OFOA module

The OFOA module is designed to determine the number of opcodes to be inserted and then integrated back into the APK, as shown in Fig. 4. It was crucial to process the generated data meticulously to ensure it conformed precisely to the specifications associated with the opcode distribution characteristic of the Data Transformation Post-Generation Process. To eliminate negative values, an absolute operation is applied to the generated vectors. For cost-effective modifications, vectors exhibiting infeasible distributions are removed. Subsequently, the remaining vectors undergo normalization, culminating in the formation of a feature database. It was crucial to conduct comprehensive back-end data execution on the created data to ensure that the distribution of operation code features strictly adhered to the required specifications. This meticulous data processing involved intricate adjustments and manipulations to align the opcode distribution features with the desired standards and constraints. By processing the data on the back end, we meticulously tailored the opcode distribution features to precisely meet the specified requirements, ensuring accuracy and compliance with the desired criteria.

The deconstruction of malware is a crucial initial phase in the AOFA (Android Opcode Frequency Analysis) module, intended to extract vital characteristics from Android malware specimens. This procedure entails transforming the executable code of the malware into a human-readable format by deconstructing it into Dalvik bytecode. The retrieved bytecode comprises opcodes and other essential attributes, offering significant insights into the malware’s behaviour and operation. Through the analysis of opcode sequences and their frequency, the module can gain insights into the fundamental operations of the virus. The program concurrently extracts benign features from an established feature library to ascertain a comparative baseline. These innocuous characteristics signify standard application behaviour and are crucial for differentiating between authentic and possibly harmful acts. Comparing benign and malware characteristics facilitates the detection of behavioural differences that may signify harmful activiy Upon acquisition of both malware and benign properties, the module executes comparative calculations to assess their similarities and discrepancies. Metrics like Jaccard similarity and cosine similarity are used to assess the overlap or divergence of feature sets. These calculations assist in identifying variations from typical behaviour, which frequently signify suspicious or harmful activities. The AOFA module employs a systematic analysis to facilitate malware identification by concentrating on opcode-level behaviour. Opcode insertion is a crucial procedure in obfuscating Android malware, aimed at adding complexity to the executable code while maintaining its functionality.

Upon recognizing substantial disparities between malware and benign apps, the module readies itself to strategically incorporate more opcodes into the malware’s opcode sequences. The meticulous choice of insertion places guarantees that the supplementary opcodes obfuscate detection mechanisms while maintaining the functional integrity of the malware. The opcode insertion function is employed, systematically incorporating the chosen opcodes into the malware’s sequences. This function is intended to position the opcodes at strategically recognized areas established during the analysis step. The insertion procedure modifies the executable code’s structure by adding new layers of complexity, hence complicating the detection of malicious intent by static and dynamic analysis tools. By altering the code, the module efficiently readies the virus for obfuscation. Upon completion of the opcode insertion process, the module advances to reconstruct the malware into a new APK file. This phase guarantees that the obfuscated malware, now embedded with the inserted opcodes, is appropriately packed in a format suitable for deployment and execution on Android devices. Reconstructing the APK is an essential concluding step, as it ensures that the alterations do not compromise the malware’s operation and that the file is prepared for additional testing against detection systems. This method enables the concealed malware to circumvent detection systems while preserving its inherent functionality.

Target detection models

To thoroughly evaluate the efficacy of DOpGAN, the current method for improving malware detection, a set of four sophisticated malware detection systems, was used. These systems, characterised by their dependence on opcode distribution properties, encompass a wide range of machine learning and pattern recognition techniques. The comprehensive assessment procedure is depicted in Fig. 5 and involves the following specific detection frameworks:

CNN-based detector: This advanced detector uses Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for feature extraction using one-dimensional convolutional layers. The employment of CNNs facilitates the automatic recognition of complex patterns in opcode distributions, demonstrating the detector’s sophisticated capacity to capture the subtle intricacies of malware signatures

Kaggle-RF detector: Originating from a highly regarded machine learning competition platform, this detector employs a Random Forest (RF) algorithm. Known for its ensemble learning technique, the Random Forest framework combines multiple decision trees to improve classification accuracy and prevent overfitting, making it a robust choice for malware detection.

SVM-based detector: This detection system employs a support vector machine technique with a linear kernel function. Renowned for its efficacy in high-dimensional domains, SVMs excel in classification tasks by identifying and constructing an ideal separating hyperplane. This hyperplane differentiates between classes with the maximum achievable margin, enabling precise malware detection.

KNN-based detector: This detector uses the K-Neighbours Classifier from the Scikit-learn library, employing a straightforward yet successful methodology. The KNN-based detector identifies new instances by calculating the distance between sample points, identifies the nearest neighbours using majority voting among these neighbours, and offers a straightforward method for malware detection. Additionally, VirusTotal, which encompasses many malware detection techniques, was employed to evaluate the effects of DOpGAN.

Analysis and results

In this section, we assess the efficacy of our model by calculating and analysing its recall, precision, and accuracy metrics. We now show the experimental results for our proposed method. This empirical assessment forms the basis for drawing analytical conclusions about the effectiveness of our malware creation method.

Implementation of proposed framework

The proposed framework consists of two main components: a Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN) and an Opcode Feature Alteration (OFOA) module. Initially, the DCGAN is employed to learn and generate faked benign APK opcode distribution features, which are then refined through the OFOA module by incorporating supplementary opcodes into the original APK before repackaging the file. The DCGAN model is trained using a 200-dimensional random noise vector as input, leveraging the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0002 and beta1 set to 0.5. The generator employs ReLU and Tanh activation functions, while the discriminator utilizes Leaky ReLU. The training process, conducted on an AMD Ryzen 7 CPU with an NVIDIA RTX 3050Ti GPU and 16 GB of RAM, spans 200 epochs with a batch size of 64. Two discriminators are iteratively trained: one to distinguish between benign and malicious samples, and another to differentiate adversarial from regular examples. The evaluation of the framework involves multiple metrics, including Modification Success Rate (MSR), Average Success Rate (ASR), Amount of Opcode Insertions (AMC), and Concluded Success Rate (CSR), in addition to precision, recall, and F-score. Furthermore, dataset-specific details are incorporated to address potential biases, utilizing benign samples from the XiaoMi app store and malicious samples from the VirusShare database.

Opcode distribution feature generation module

The module assigned for producing opcode distribution features was developed by adapting a modified Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Network (DCGAN). This modified architecture uses random noise as input to produce synthetic characteristics of benign opcode distributions and their results. This approach entails complex neural network architectures designed specifically for generating features, enabling the correct depiction of benign opcode distributions.

OFOA module

The initial input consists of a disassembled malware file, which furnishes features such as opcodes and API calls. Using an “Opcode insert function,” these features are harnessed to construct novel, obfuscated malware variants, enhancing their resistance to detection. To ascertain the realism of the generated malware, a comparison is conducted with a “Feature library” containing known malicious samples. Once a satisfactory degree of similarity is achieved, opcodes are integrated, and the code is reconstructed into an APK file. Through disassembly, features are extracted from both the original and generated malware, facilitating the evaluation of their disparities.

Dataset

In this study, we utilized a comprehensive dataset to evaluate the performance of DOpGAN, ensuring a robust and representative evaluation of its capabilities in malware detection. The dataset comprises malware samples collected from three widely-used repositories, each contributing to the diversity and reliability of the dataset. The first source, VirusTotal, is a large-scale malware detection service that provides a wealth of labeled malware samples, facilitating extensive analysis of different malware variants. The second source, the Drebin dataset, serves as a benchmark for Android malware detection and includes over 5,000 malware samples, offering valuable insight into the Android malware landscape. Lastly, the AndroZoo dataset, a continuously updated repository of Android applications, includes both benign and malicious APKs, further enriching the dataset with diverse real-world samples.

The dataset consists of 10,000 APK samples, categorized into two main classes: malicious and benign. The malicious samples account for 6500 APKs and are further divided into four malware families: Trojans (2,500 samples), which inject malicious code into legitimate applications; Ransomware (1500 samples), which encrypts user data and demands payment for its release; Spyware (1500 samples), which monitors user activity and exfiltrates sensitive information; and Adware (1000 samples), which generates intrusive advertisements to monetize the application. The benign samples, totaling 3500, were collected from trusted sources, including the Google Play Store and F-Droid, ensuring a representative set of legitimate applications for comparison.

Evaluation method

In the DOpGAN dataset, all malware samples are solely designated for testing purposes. The samples are processed by DOpGAN prior to being reintegrated into target attack models for additional analysis. The assessment of the model includes four essential parameters. The evaluation metrics in the manuscript are designed to assess DOpGAN’s evasion performance. The percentage of malware samples that have been altered while still functioning is known as the Modification Success Rate, or MSR. The mean evasion success among classifiers is determined by the Average Success Rate (ASR). The alterations performed to guarantee that there are as few disruptions as possible for stealth are measured by the Amount of Opcode Modifications (AMC). MSR and ASR are used to create the Concluded Success Rate (CSR), which assesses overall evasion. The detection model’s performance is measured by precision, recall, and F1-score. We measured the time complexity of creating adversarial samples to gauge practical application, and DOpGAN achieved an efficient rate of 2.1 ms/sample. Analysis of resource usage further demonstrated that DOpGAN works well on computers with moderate processing power, making practical implementation possible.

The study employed four detection models and conducted ten-fold cross-validation to evaluate the efficacy of evasion. The results are presented in Table 3. The findings indicate that each detection model effectively identifies malware, suggesting the attack system’s efficacy when a substantial fraction of modified malware is erroneously classified as benign APKs.

The Modification Success Rate is a measure that indicates DOpGAN’s effectiveness in altering malware across different sizes of benign feature databases. Secondly, the Average Success Rate offers insight into the probability of modified malware successfully circumventing detectors, assessing the system’s resilience. Thirdly, the Amount of Opcode implantation parameter measures the degree of implantation within the virus, providing critical insights into the level of manipulation accomplished by DOpGAN. Finally, the Concluded Success Rate encompasses the ultimate evasion success rate of DOpGAN across several detection systems, indicating its overall efficacy.

Furthermore, the assessment is augmented using metrics like Precision, Recall, F-score, and False Negative Rate, providing a comprehensive analysis of the model’s performance and efficacy.

The entirety of the test dataset, comprising 5017 malware samples, is submitted to DOpGAN for alteration. The Modification Success Rate is recorded in Table 4. The modified AndrOpGAN APK samples are subsequently forwarded to detectors for analysis. The resulting Evasion Success Rate is displayed in Table 5. The comprehensive evaluation of 5017 malware samples through the lens of DOpGAN modification and subsequent detector analysis yields profound insights into the adaptive capabilities of modern malware against defensive mechanisms. The modification success rates, as captured in Table 4, demonstrate a remarkable progression, with the success rate escalating significantly alongside the increase in database size, ultimately achieving a perfect success rate of 100% for databases sized at 10,000 samples and beyond. Further analysis of the modified AndrOpGAN APK samples against various detectors unveils nuanced evasion capabilities, as detailed in Table 5

Here, the evasion success rates exhibit a marked increase with the expansion of the dataset, peaking at a 100% evasion rate for databases with 10,000 to 13,000 samples across multiple detection models, including MSR, KNN, SVM, Kaggle-RF, and CNN. This indicates a high degree of adaptability and sophistication in the modified samples, enabling them to circumvent traditional detection mechanisms with considerable success. The modified DOpGAN APK samples are forwarded to detectors for analysis. The resulting Evasion Success Rate is displayed in Table 6. This analysis of DOpGAN-modified APK samples showcases even more striking evasion success rates, with nearly all models achieving or approaching a 100% evasion rate for database sizes of 3,000 samples and upwards. This underscores the potent challenge that such modified malware presents to current detection frameworks, highlighting the urgent need for cybersecurity measures to counteract advanced threats effectively.

In Fig. 6, the Modified Success Rate is presented across varying dataset sizes. The figure illustrates the success rates with different detection models, demonstrating the beneficial impact of dataset size on the evasion success rate.

In Fig. 7 Comparison of Evasion Success Rates with AndrOpGAN. With the continual expansion of the size of the database, the bypassing success rates for numerous systems are observed to increase.

In Fig. 8 Comparison of Evasion Success Rates with DOpGAN. With the continual expansion of the size of database, the bypassing success rates for numerous models are observed to increase.

In our endeavor to thoroughly comprehend the superiority of DOpGAN over AndrOpGAN, we delve into the intricacies of their respective training methodologies. It is imperative to recall that the success of an attack method hinges on its ability to achieve two pivotal objectives: breaching firewalls and outwitting malware detectors. Upon closer scrutiny, a distinct disparity emerges between AndrOpGAN and DOpGAN. AndrOpGAN, it appears, tends to concentrate on fulfilling one objective at the expense of the other. This becomes apparent when we analyze the outcomes of AndrOpGAN when applied to detectors, as depicted in Fig. 6.

Upon scrutinizing the examples generated by AndrOpGAN, a discernible pattern emerges: many of these examples indeed manage to deceive the adversarial example detector, but they are just as swiftly identified by the malware detector. Consequently, it becomes evident that AndrOpGAN struggles when confronted with the task of simultaneously addressing both objectives. This characteristic renders AndrOpGAN more suitable for single-objective tasks where the focus is more specialized.

In stark contrast, DOpGAN showcases a remarkable ability to adeptly handle these dual objectives and strike a balance between them. To provide clarity, we present the results of DOpGAN when applied to detectors in Fig. 8. Here, the majority of the generated examples exhibit the remarkable ability to evade detection from both adversarial example detectors and malware detectors. The superiority of DOpGAN over AndrOpGAN can be attributed to a pivotal design choice - the incorporation of two Discriminators. This strategic inclusion acts as a potent motivator for the Generator, pushing it to tackle both objectives simultaneously throughout the rigorous training process.

State-of-the-art comparison of android malware detection methods

A dual-objective GAN model called DOpGAN was created to avoid adversarial example and malware detection. With a low false positive rate of 4.8% and a high evasion success rate of 95.4%, it is an extremely powerful tool for detecting hostile malware. MalGAN36, a black-box evasion model, by contrast, has a 92.3% success rate but a little lower detection accuracy. Though it has a slower real-time feasibility and a higher false positive rate of 12.7%, Defensive Distillation uses knowledge distillation for robust models.

Models are retrained using adversarial examples in Adversarial Training, which provides balanced performance but still has slower processing times and 10.4% false positives. Optimization-based adversarial detection is used in recent techniques such as PAD40, which achieve 90.9% detection accuracy with enhanced real-time feasibility of 2.5 milliseconds per sample. MalPurifier41 maintains evasion success at 90.9% while improving detection accuracy to 92.0%. Graph-based models are the focus of BagAmmo14, which achieves 87.0% evasion success and 85.0% detection accuracy.

AndrOpGAN, while effective in altering opcode distributions, focuses on evading static malware detectors. However, it often fails when faced with adversarial example detectors, as it lacks a dual-objective design. In contrast, DOpGAN integrates a dual-discriminator architecture, allowing it to effectively target both malware detection systems and adversarial example detectors. This makes it significantly more robust in real-world applications. Alos, Despite its dual-discriminator framework, DOpGAN achieves comparable computational efficiency to AndrOpGAN by leveraging an optimized DCGAN structure and the Adam optimizer with an adaptive learning rate. Training on a database of 13,000 samples, DOpGAN demonstrates efficient convergence within 200 epochs, highlighting its feasibility for large-scale applications. Furthermore, DOpGAN is designed to handle large datasets without performance degradation. For instance, it maintains a consistent evasion success rate of nearly 100% even with datasets exceeding 10,000 samples. Its Opcode Feature Optimization Algorithm (OFOA) dynamically adjusts opcode modifications, ensuring adaptability across varying dataset sizes and complexities.

Ethical implications of evasive malware generation

The framework is designed to enhance malware detection by generating adversarial examples, we acknowledge the potential misuse of such techniques by attackers. To mitigate this risk, all experiments were conducted in isolated environments, and the generated adversarial APKs are intended solely for retraining and improving malware detection systems. The results are shared exclusively for academic and research purposes to ensure responsible usage. Furthermore, we emphasize the importance of collaborating with industry stakeholders to align defensive advancements with emerging adversarial threats. By leveraging adversarial samples to identify vulnerabilities in existing systems, we aim to strengthen the resilience of malware detection frameworks.

Discussion, limitations, and future work

This study illustrates how adversarial instances produced by DOpGAN might avoid detection and draws attention to flaws in malware detection systems. The work addresses how these hostile examples can reinforce defensive mechanisms by retraining current detection models, enhancing their capacity to recognize comparable evasive attempts, even when the focus is on evasion strategies. The scalability and resource requirements of DOpGAN were extensively examined in relation to real-world application. Datasets of different sizes were used to test the system, and Tables 4, 5, and 6 present performance parameters including false positives, detection accuracy, and evasion success rates. These findings demonstrate that DOpGAN continues to perform well even when dealing with bigger datasets. To further elucidate DOpGAN’s viability in practical settings, the book now includes the resource needs for training and deploying the system. lthough DOpGAN is good at avoiding static analysis by adjusting opcode distributions, it is not as effective against systems that use dynamic information, such execution traces and API call sequences, which are not the focus of DOpGAN’s current methodology. This is a result of the generator’s emphasis on static features rather than runtime behavior. To increase resistance to hybrid detection, future updates can incorporate behavior simulation into the adversarial example generation procedure.

Moreover, DOpGAN can handle larger datasets while still performing well, it trumps AndrOpGAN in terms of scalability. Even while AndrOpGAN is good at avoiding conventional malware detectors, its versatility to various dataset sizes is limited by the fact that it is made for single-objective tasks. On the other hand, DOpGAN has a dual-discriminator design that, even with growing datasets, strikes a balance between evasion for both malware and hostile example detectors. Table 4 demonstrates that DOpGAN outperforms AndrOpGAN in terms of evasion success rates on datasets with 10,000–13,000 samples, achieving nearly 100% success rates. To avoid detection without compromising scalability, DOpGAN’s design dynamically modifies opcode distributions by utilizing the Opcode Feature Optimization Algorithm (OFOA). These findings show that DOpGAN is more appropriate for practical uses involving huge datasets, guaranteeing excellent effectiveness and versatility.

Extension to other platforms and attack types

DOpGAN can be extended to different platforms, including Windows or Linux-based systems, by changing the feature extraction and generating procedures to conform to platform-specific requirements. For instance, the framework might target control-flow graphs or API call sequences frequently utilized in malware detection for other platforms rather than opcode manipulation.

Furthermore, the dual-objective architecture of DOpGAN can be modified to accommodate various attack types, such circumventing spam detection systems by changing email text or avoiding network intrusion detection systems (NIDS) by changing network traffic patterns.

Use of transformer models

We recognize that transformer-based systems have demonstrated remarkable efficacy across a range of fields, including as virus detection and natural language processing. By utilizing their contextual knowledge of opcode sequences and API call patterns, transformer models like BERT or comparable variations could improve DOpGAN’s capacity to produce adversarial samples.

Conclusion

DOpGAN presents a novel grey-box attack strategy that effectively alters opcode distribution features, enabling malware to bypass advanced Android malware detection systems. By generating adversarial examples that are misclassified as benign, DOpGAN showcases its ability to evade traditional detection mechanisms, posing a significant challenge to contemporary mobile security frameworks. This highlights the importance of integrating defensive strategies, such as adversarial example detection systems, to enhance the resilience of Android platforms against increasingly sophisticated threats. The evaluation of DOpGAN using multiple classification models and VirusTotal demonstrates its capacity to evade detection at a concerning rate, underscoring the vulnerability of current systems. However, the adversarial APKs generated by DOpGAN offer a valuable resource for retraining detectors, strengthening their ability to identify and counteract this class of malware. This continuous improvement of detection systems is vital in ensuring the long-term security of Android platforms as new and evolving threats emerge.

While DOpGAN demonstrates high evasion success against static feature-based detectors, its reliance on specific datasets, such as VirusShare for malware and XiaoMi for benign samples, may introduce biases, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results. The feature distributions in these datasets may not fully reflect real-world scenarios, necessitating future evaluations with diverse datasets like AndroZoo and Google Play Store. Additionally, integrating hybrid static-dynamic datasets and real-time behavioral analysis will provide a more comprehensive assessment of DOpGAN’s effectiveness against advanced detection systems employing behavioral analysis, hybrid methodologies, or ensemble approaches. These future directions will enhance the framework’s applicability in practical cybersecurity environments.

Data availability

The data produced or analysed in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Change history

02 May 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Funding section in the original version of this Article was omitted. It now reads: “This work is funded under Project No. SEED-CCIS-2023-151 by Prince Sultan University.”

References

Adekotujo, A., Odumabo, A., Ademola, A. & Aiyeniko, O. A comparative study of operating systems: Case of windows, unix, linux, mac, android and iOS. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 176, 16–23. https://doi.org/10.5120/ijca2020920494 (2020).

Alkahtani, H. & Aldhyani, T. H. Artificial intelligence algorithms for malware detection in android-operated mobile devices. Sensors 22, 2268 (2022).

Almomani, I., Ahmed, M. & El-Shafai, W. Android malware analysis in a nutshell. PLoS ONE 17, e0270647 (2022).

Almomani, I. M. & Al Khayer, A. A comprehensive analysis of the android permissions system. IEEE access 8, 216671–216688 (2020).

Bai, T. et al. Ai-gan: Attack-inspired generation of adversarial examples, in 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP) 2543–2547. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP42928.2021.9506278 (2021).

Al Khayer, A., Almomani, I. & Elkawlak, K. Asaf: Android static analysis framework, in 2020 First International Conference of Smart Systems and Emerging Technologies (SMARTTECH) 197–202 (IEEE, 2020).

Ijaz, M., Durad, M. H. & Ismail, M. Static and dynamic malware analysis using machine learning, in 2019 16th International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technology (IBCAST) 687–691. https://doi.org/10.1109/IBCAST.2019.8667136 (2019).

Huang, S., Papernot, N., Goodfellow, I., Duan, Y. & Abbeel, P. Adversarial attacks on neural network policies. arXiv arXiv:1702.02284 (2017).

Kolter, J. Z. & Maloof, M. A. Learning to detect malicious executables in the wild, in Proceedings of the Tenth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 470–478 (2004).

Mao, X. & Li, Q. Generative Adversarial Networks (gans) 1–7 (2021).

Zhang, X., Wang, J., Sun, M. & Feng, Y. Andropgan: An opcode gan for android malware obfuscations, in Machine Learning for Cyber Security: Third International Conference, ML4CS 2020, Guangzhou, China, October 8–10, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 12–25 (Springer, 2020).

Croce, F., Andriushchenko, M., Singh, N. D., Flammarion, N. & Hein, M. Sparse-rs: A versatile framework for query-efficient sparse black-box adversarial attacks, in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 36, 6437–6445 (2022).

Rathore, H., Sahay, S. K., Nikam, P. & Sewak, M. Robust android malware detection system against adversarial attacks using q-learning. Inf. Syst. Front. 23, 867–882 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Black-box adversarial example attack towards \(\{\)FCG\(\}\) based android malware detection under incomplete feature information, in 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23) 1181–1198 (2023).

Maiorca, D., Demontis, A., Biggio, B., Roli, F. & Giacinto, G. Adversarial detection of flash malware: Limitations and open issues. Comput. Secur. 96, 101901 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Shadowdroid: Practical black-box attack against ml-based android malware detection, in 2021 IEEE 27th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS) 629–636 (IEEE, 2021).

Xu, G. et al. Ofei: A semi-black-box android adversarial sample attack framework against dlaas. IEEE Trans. Comput. 73, 956–969 (2023).

Bostani, H. & Moonsamy, V. Evadedroid: A practical evasion attack on machine learning for black-box android malware detection. Comput. Secur. 139, 103676 (2024).

Grosse, K., Papernot, N., Manoharan, P., Backes, M. & McDaniel, P. Adversarial examples for malware detection, in Computer Security–ESORICS 2017: 22nd European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Oslo, Norway, September 11-15, 2017, Proceedings, Part II 22 62–79 (Springer, 2017).

Berger, H., Hajaj, C. & Dvir, A. When the guard failed the droid: A case study of android malware. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.14123 (2020).

Yildiz, O. & Doğru, I. A. Permission-based android malware detection system using feature selection with genetic algorithm. Int. J. Software Eng. Knowl. Eng. 29, 245–262 (2019).

Radford, A., Metz, L. & Chintala, S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv arXiv:1511.06434 (2016).

Hadiprakoso, R. B., Kabetta, H. & Buana, I. K. S. Hybrid-based malware analysis for effective and efficiency android malware detection, in 2020 International Conference on Informatics, Multimedia, Cyber and Information System (ICIMCIS) 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIMCIS51567.2020.9354315 (2020).

Du, C. & Zhang, L. Adversarial attack for SAR target recognition based on UNet-generative adversarial network. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13214358 (2021).

Li, H., Zhou, S., Yuan, W., Li, J. & Leung, H. Adversarial-example attacks toward android malware detection system. IEEE Syst. J. 14, 653–656. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2019.2906120 (2020).

Wang, X., He, K., Song, C., Wang, L. & Hopcroft, J. E. At-gan: An adversarial generative model for non-constrained adversarial examples. IEEE Syst. J. (2021).

Chen, J., Zheng, H., Xiong, H., Shen, S. & Su, M. MAG-GAN: Massive attack generator via GAN. Inf. Sci. 536, 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2020.04.019 (2020).

Xiao, C. et al. Generating adversarial examples with adversarial networks. arXiv arXiv:1801.02610 (2018).

Zhao, G., Zhang, M., Liu, J. & Wen, J.-R. Unsupervised adversarial attacks on deep feature-based retrieval with gan arXiv arXiv:1907.05793 (2019).

Hu, W. & Tan, Y. Generating adversarial malware examples for black-box attacks based on gan. arXiv arXiv:1702.05983 (2017).

Nazemi, A. & Fieguth, P. Potential adversarial samples for white-box attacks. arXiv arXiv:1912.06409 (2019).

Narodytska, N. & Kasiviswanathan, S. P. Simple black-box adversarial attacks on deep neural networks, in CVPR Workshops, Vol. 2, 2 (2017).

Liu, A. et al. Perceptual-sensitive gan for generating adversarial patches, in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 33, 1028–1035 (2019).

Goodfellow, I. J., Shlens, J. & Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6572 (2014).

Papernot, N. et al. Practical black-box attacks against machine learning, in Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security 506–519 (2017).

Hu, W. & Tan, Y. Generating adversarial malware examples for black-box attacks based on gan, in International Conference on Data Mining and Big Data, 409–423 (Springer, 2022).

Carlini, N. & Wagner, D. Towards evaluating the robustness of neural networks, in 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (sp), 39–57 (IEEE, 2017).

Xu, L. & Zhai, J. Dcvae-adv: A universal adversarial example generation method for white and black box attacks. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 29, 430–446 (2023).

Kang, B., Yerima, S. Y., McLaughlin, K. & Sezer, S. N-opcode analysis for android malware classification and categorization, in 2016 International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security), 1–7 (2016).

Li, D. et al. Pad: Towards principled adversarial malware detection against evasion attacks. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secure Comput. 21, 920–936 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Cheng, G., Chen, Z. & Yu, S. Malpurifier: Enhancing android malware detection with adversarial purification against evasion attacks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.06423 (2023).

Papernot, N., McDaniel, P., Wu, X., Jha, S. & Swami, A. Distillation as a defense to adversarial perturbations against deep neural networks, in 2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP) 582–597 (IEEE, 2016).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thanks Prince Sultan University for paying the APC of this publication.

Funding

This work is funded under Project No. SEED-CCIS-2023-151 by Prince Sultan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Naveed Ahmed: Lead on conceptualization, Methodology, Writing of the original draft, Material preparation, Data collection, Analysis. Amjad Rana Saleem: Contributed to review and editing, Material preparation, Data collection, Analysis. Hassan Jalil Hadi: Responsible for detail review of study. Faisal Bashir Hussain: Detailed review and editing of the manuscript. Mohammaed Ali Alshara: Responsible for detail review of study. Prasun Chakrabarti: Contributed to review and editing, Material preparation, Data collection, Analysis. Tulika Chakrabart: Provided supervision, Project administration.