Abstract

Integrating renewable energy (RE) into electricity generation enhances sustainability, reduces greenhouse gas emissions, improves energy security, lowers costs, and supports sustainable development, particularly in remote and underserved regions. This study evaluates the feasibility and performance of a hybrid renewable energy system (HRES) designed to meet the energy demands of Hobyo Seaport, Somalia. The proposed HRES incorporates a photovoltaic (PV), wind turbines (WT), diesel generator (DG), pumped hydro energy storage (PHES), and battery energy storage system (BESS). Four configurations—PV/WT/PHES, PV/WT/DG/PHES, PV/WT/DG/BESS, and WT/DG/PHES—were analyzed using HOMER Pro and MATLAB software to optimize system sizing and assess techno-economic and environmental performance. Results indicate that the PV/WT/PHES configuration is the most efficient, achieving a 100% renewable energy fraction, a net present cost of $619,720, the lowest levelized cost of electricity at $0.03845/kWh, and a simple payback period of 0.31 years. Additionally, the system offers significant environmental benefits, mitigating 1,029 tons of CO annually, valued at $20,593 in carbon credits. Over a 20-year period, it reduces cumulative cash flow by 97.1% compared to a diesel-based system. These findings highlight the proposed HRES as a cost-effective and environmentally advantageous solution, establishing its sustainability and practicality for enhancing energy infrastructure in Somalia’s Seaports and similar coastal regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

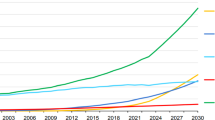

Global energy demand has risen significantly with industrial development, while conventional energy sources are declining1. Fossil fuels have historically become the primary energy source and accounted for most of this growth. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), fossil fuels in the global energy mix declined from 82% in 2013 to 80% in 2023, while clean energy met 40% of a 15% rise in energy demand. Consequently, global CO2 emissions from energy sources rose by 1.3% in 2023, reaching 37.3 gigatonnes2. If this trend continues, carbon emissions will further rise, posing challenges to limiting global temperature increases to below 2 °C3. Given the finite nature of fossil fuels and the environmental challenges, there is growing support for an “energy transition” towards renewable sources to ensure sustainable, low-carbon energy for the future. In the future, electricity will be key to addressing two main issues: fulfilling energy needs and reducing carbon emissions4,5. Global electricity consumption is projected to double by 20506. However, if fossil fuels continue to be the primary energy source, CO2 emissions are expected to increase significantly. In 2022, electricity production accounted for 261 Mt of global CO2 emissions7, with only 28% of electricity generated from renewables2 By 2050, renewable energy (RE) is projected to supply 91% of global energy, with solar and wind contributing significantly, and to generate 60% of global electricity8.

Numerous studies have examined the performance of RE sources in electricity generation, either as stand-alone energy systems for domestic load9, in conjunction with conventional grid systems10, or off-grid systems11. Hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES) have emerged as optimal solutions for addressing the increasing demand for electricity, mitigating fossil fuel consumption, and resolving the environmental and economic challenges associated with conventional energy sources12,13,14. Concurrently, substantial research and development efforts in this area are focused on the energy needs of several countries, as detailed in Table 1.

Samatar et al.15 proposed and evaluated an HRES for rural electrification in Somalia. The proposed system comprises photovoltaic (PV) panels, a wind turbine (WT), a diesel generator (DG), and a battery energy storage system (BESS). The performance of the proposed system was numerically investigated in terms of techno-economic and environmental analyses using HOMER and MATLAB. The obtained results were compared with alternative HRES configurations, namely PV/WT/BESS and PV/DG/BESS. The analysis revealed that the proposed system achieves a net present cost (NPC) of $96.9k and a levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) of $0.090/kWh. Additionally, the system demonstrates a RE penetration rate of 91.8% and a 53.34% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. These results confirm the proposed system’s superior feasibility for achieving sustainable rural electrification. In another work published by Samatar et al.16, the techno-economic feasibility of a PV/DG/BESS hybrid system is investigated. The HRES is proposed for rural electrification in the Lower Shabelle region of Somalia. The performance of the proposed system was analyzed using HOMER Pro and compared to the PV/BESS and DG/PV configurations. The results show that the proposed PV/DG/BESS hybrid system exhibits superior economic performance, with an NPC of $129.7k, an LCOE of $0.180/kWh, and a lower payback period of 1.8 years. Environmentally, the proposed configurations result in an emission of 12.41 tons/yr. Kerboua et al.17 investigate the feasibility of a grid-connected PV/WT hybrid energy system using HOMER and MATLAB software to replace the existing energy setup. The results show that the hybrid system offers competitive energy costs compared to most European countries. However, the cost of public grid energy in the region is six times lower due to government subsidies. Bouregba et al.18 evaluated the energy efficiency of an urban dairy farm in Tlemcen, Algeria, by assessing the feasibility of a grid-connected PV/wind hybrid energy system. HOMER and MATLAB software explored replacing the farm’s existing energy systems with the hybrid system, integrated into a low-voltage electrical grid. The optimization focused on minimizing NPC, LCOE, and CO2 emissions while maximizing the renewable fraction (RF). The results demonstrate the proposed system’s significant economic and environmental benefits compared to the current energy configuration, with a total grid sale of 42,488 kWh/yr. The economic assessment shows an NPC of $106.12k, an LCOE of $0.0959/kWh, and a payback period of 33 months. Environmentally, the proposed HRES can mitigate approximately 594 kg of CO2/d, with an RF of 98%. Kushwaha et al.19 optimized an off-grid microgrid for rural India using two different optimization algorithms: the Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). Key technical, economic, and environmental factors were analyzed across various energy configurations. The PV-WT-MG-DGs-battery-converter system was identified as the optimal solution, with SMA outperforming PSO in terms of efficiency, global optimization capability, and computational speed. Bilal et al.20, have highlighted the potential of HRES to address energy challenges in remote and underserved regions. Their findings underscore the importance of optimizing HRES configurations to ensure cost-effectiveness, reliability, and sustainability, particularly in areas with limited access to conventional grid infrastructure.

Previous studies have demonstrated the high feasibility of utilizing RE sources for electricity production. However, most research focuses on conventional energy storage systems, primarily relying on various types of batteries, such as lithium-ion and lead-acid batteries. Notably, these batteries have a limited life cycle21, necessitating replacements throughout the lifecycle of HRES. This replacement requirement significantly increases the capital cost of such systems. Additionally, the batteries’ manufacturing and recycling phases consume substantial amounts of energy and contribute to elevated levels of carbon emissions. These two challenges, short operational lifespan and high environmental impact highlight the limitations of conventional batteries, making them less favorable as an energy storage option. Pumped hydro energy storage (PHES) has emerged as a suitable energy storage system, offering several advantages, including a long lifecycle, virtually unlimited storage capacity, and a clean energy storage solution22. Numerous researchers have investigated the performance of PHES systems within HRES. A comprehensive summary of this work is presented in the review by23,24. PHES systems show higher feasibility in terms of supporting 100% energy in remote communities25. Yimen et al.26 present a techno-economic evaluation of a PV/WT/BG hybrid system with PHES for electrifying a small village in northern Cameroon using HOMER software. The findings indicate that by 2030, the proposed HRES incorporating PHES is estimated to provide affordable, reliable, and modern energy access. Jurazs et al.27 investigate the performance of a PV/WT/PHES hybrid system under the climatic and operational conditions of Lower Silesia, Poland. Geographic Information System tools are employed to estimate the solar and wind capacity potential of the region’s solar and wind capacity potential. The study explores the feasibility of reducing both emissions and overall costs while increasing the share of RE. A significant finding reveals that the RE share rises to 50% when the carbon dioxide price reaches €30/ton. Pali et al.28 present a novel PV system integrated with PHES to ensure continuous power generation at a stable voltage for rural areas and regions with access to open wells or water sources. The performance of the proposed HRES is evaluated numerically using MATLAB based on real solar irradiation data. The system utilizes PHES to deliver reliable, high-quality power unaffected by fluctuations or the absence of solar irradiation, eliminating the need for batteries, inverters, transformers, or complex circuitry. The results demonstrate that the proposed system offers a sustainable, uninterrupted energy solution. Liu et al.29 evaluated an innovative PV/WT/PHES/BESS hybrid system, focusing on optimizing hydropower operations during the dry season by minimizing discrepancies in monthly water consumption while accounting for water flow constraints and battery storage fluctuations. The study confirmed the system’s feasibility in mitigating water shortages for hydropower generation. Guezgouz et al.30 conducted a detailed performance analysis of a hybrid PV/WT/PHES/BESS system, emphasizing optimal sizing and sensitivity analysis. The study found that hybrid storage systems reduce electricity costs by 3.5 times and achieve a 290% reduction in curtailment compared to single storage systems.

The literature highlights the significant advantages of implementing HRES to supply electricity in isolated areas. Advancements in this research field primarily focus on exploring diverse configurations, operating conditions, and geographical locations. While RE systems have been widely studied, Somalia’s unique geographical and socio-economic context, particularly for seaport energy needs, remains underexplored. Existing research on HRES in Somalia has focused mainly on rural electrification, with limited attention to critical infrastructure like seaports. This study addresses this gap by proposing a fully renewable HRES for Hobyo Seaport, integrating PHES as a sustainable alternative to conventional batteries, which are limited by short lifespans, high costs, and environmental impacts. Current HRES studies often emphasize either economic or environmental aspects, lacking integrated techno-economic evaluations. Additionally, region-specific requirements for countries like Somalia are overlooked, and lifecycle environmental time (LCT) analysis—critical for long-term feasibility—is rarely incorporated31. By introducing PHES and LCT analysis, this study provides a comprehensive, scalable, and sustainable energy solution tailored to Somalia’s seaport infrastructure, setting a new benchmark for renewable energy research in underserved regions. However, the primary research question addressed in this study is: How can a fully HRES be optimally designed and implemented to meet the energy demands of Hobyo Seaport, Somalia, while ensuring cost-effectiveness, environmental sustainability, and long-term reliability? This question is addressed through a detailed techno-economic and environmental analysis of various HRES configurations, with a focus on the integration of PHES as a sustainable alternative to conventional battery storage systems. Therefore, the novelty of this study lies in its comprehensive techno-economic and environmental analysis of a fully HRES specifically designed for seaport infrastructure in Somalia, a region that has been largely overlooked in previous research32. Unlike existing studies that predominantly focus on conventional battery storage systems, this work introduces PHES as a sustainable and scalable alternative, offering an extended lifecycle and reduced environmental impact. Furthermore, this study integrates a detailed lifecycle environmental assessment, ensuring long-term sustainability, and provides a replicable model for other remote and underserved regions. The proposed PV/WT/PHES configuration achieves 100% RE integration, demonstrating significant cost-effectiveness and environmental benefits, which sets it apart from previous works in the field. The key contributions of this research are summarized as follows:

-

A detailed techno-economic assessment of an HRES designed specifically for seaport energy requirements.

-

Feasibility analysis of achieving full RE integration through a hybrid energy system for powering seaports in Somalia.

-

Incorporates a comprehensive lifecycle environmental assessment, ensuring the proposed system’s long-term sustainability.

-

Introduces PHES as a viable alternative to conventional batteries, highlighting its benefits in terms of extended lifecycle, reduced emissions, and scalability.

Methodology

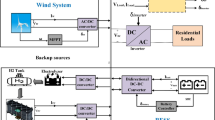

This section outlines the tools and methodology employed for optimizing an HRES to establish a sustainable microgrid. The study models and optimizes systems integrating PV, WT, PHES, BESS, DG, and power converters. PV and WT serve as the primary energy sources, with DG acting as a backup. Excess energy generated is stored in PHES and BESS to address energy deficits during periods of low generation. The proposed framework, illustrated in Fig. 1, encompasses site selection, resource assessment, load data analysis, and the definition of key constraints, such as NPC, LCOE, and carbon emissions.

HOMER Pro® software is utilized for its multi-objective optimization capabilities, which balance competing objectives, including minimizing LCOE and NPC, maximizing RE penetration, reducing carbon emissions, and ensuring system reliability. In this study, these objectives were optimized to identify cost-effective, sustainable, and reliable energy system configurations. The proposed methodology was validated through a comparative analysis of HRES performance against diesel-only and storage-supported hybrid systems. The results demonstrate that the PV/WT/PHES configuration outperforms other systems in terms of cost-effectiveness, environmental sustainability, and energy reliability. Case studies further confirm its robustness and feasibility for remote off-grid applications.

Description of the location and load profile

The current energy situation in Hobyo, Somalia, particularly its coastal regions, presents significant challenges due to limited infrastructure, reliance on diesel generators, and high energy costs. Hobyo Seaport, strategically located on Somalia’s central coast at 5°21.1’N and 48°31.5’E, serves as a key hub for regional trade due to its proximity to southern Ethiopia and vital Indian Ocean shipping routes. However, the port’s development is hindered by insufficient infrastructure and heavy dependence on diesel generators, resulting in high operational costs and environmental pollution. These energy constraints limit the port’s operational efficiency and economic potential. Recent development proposals emphasize the urgent need to modernize Hobyo’s infrastructure, particularly through the establishment of reliable energy systems essential for supporting port operations, enhancing transportation networks, and powering container processing facilities and ancillary services. This study aims to address these challenges by proposing an HRES to provide a cost-effective, reliable, and sustainable energy solution, thereby enhancing Hobyo’s operational capacity and fostering regional economic growth and integration.

Figure 2 highlights variability in load power consumption, with Subplot (a) showing consistent daily demand patterns and Subplot (b) indicating peak load distributions. This variability necessitates a microgrid system with energy storage, RE integration, demand response mechanisms, load forecasting, and HRES. Such a system would ensure a reliable, cost-effective, and sustainable energy supply, addressing the fluctuating demands evident in the data. Based on the load demand, the daily energy consumption is calculated to be 2,042.70 kWh. HOMER software was employed to determine the peak load, which was found to be 245.62 kW, ensuring the system’s reliability in meeting the daily load requirements. To account for the variability in the seaport’s daily power demand, random time-step and day-to-day fluctuations of 8.05% and 12.075%, respectively, were incorporated into the HOMER analysis to predict the proposed system’s peak load accurately. The study established baseline and scaled energy values of 4,564.10 and 2,042.70 kWh/d, respectively. Additionally, the analysis revealed a scale load of 245.62 kW and a baseline electric load of 548.80 kW, providing critical insights into the system’s performance parameters.

Modeling of system components

HRES integrates multiple energy sources, storage systems, and power converters to manage generation, storage, and load demands efficiently. The proposed HRES for Hobyo Seaport, as illustrated in Fig. 3, combines RE sources, such as WT and PV systems, with conventional sources like DG to ensure a reliable energy supply. Power converters enable seamless energy exchange between AC and DC buses, ensuring compatibility across diverse components. Energy storage systems, including BESS and pumped storage systems, play a critical role in balancing supply and demand. Excess RE is stored during low-demand periods and discharged during high-demand or low renewable availability. An integrated energy management strategy prioritizes RE sources, relying on the DG only when necessary to maintain system reliability. This coordinated operation ensures a sustainable, reliable, and efficient energy supply for diverse applications, including seaports and remote areas.

Mathematical modeling

This subsection presents the mathematical models for each component of the proposed system. These models form the basis for analyzing and evaluating the performance of each component. The objective is to comprehensively understand the system’s behavior under the specific operating conditions of Hobyo Seaport, Somalia.

Wind turbine

Nowadays, electricity production using wind turbine energy systems has gained significant attention worldwide, particularly in regions with high wind velocity. These systems efficiently convert wind energy into electricity through a two-step process. First, the wind’s power is transformed into kinetic energy using a WT, and then this kinetic energy is converted into mechanical energy to drive an electric generator. In this study, a WT with a rated output of 10 kW and a hub height of 24 m with a lifetime of 20 years was selected. The mechanical power (\(\:{P}_{m}\)) generated by the WT can be calculated as follows

where \(\:\rho\:\), \(\:V\), and \(\:{\rm\:A}\) represent the density of the air (1.22 kg/m3), wind speed (m/s), and the area moved by the rotor (m2), respectively.

The electrical power (\(\:{P}_{e}\)) of the WT can be calculated in Eq. (2)

where \(\:{C}_{p}\) refers to the power coefficient of a WT.

Therefore, the overall power output of the selected WT can be calculated as follows46:

where \(\:{P}_{r}\), \(\:{V}_{C,in}\), and \(\:{V}_{c,out}\) represent the rated output power of the WT, cut-in wind speed, and cut-out wind speed, respectively.

Photovoltaic system

Solar PV systems are devices that directly convert sunlight into electricity through a chemical reaction. These systems are highly recommended for domestic and larger energy production stations due to their competitive pricing, environmental benefits, and ease of implementation. However, the output of these systems depends on several factors, including solar radiation, ambient temperature, tilt angle, and degradation effects. In this study, the SunPower E20-327 PV module is considered for investigation. This model consists of 96 monocrystalline cells, with a nominal power output of 0.327 kW, a conversion efficiency of 20.4%, and a power temperature coefficient degradation rate of -0.38%/°C. The electrical output of the PV array can be estimated using Eq. (4)47.

where \(\:{Y}_{PV}\:\), \(\:{{\upalpha\:}}_{\text{P}}\), \(\:{f}_{PV}\), \(\:{G}_{T}\), \(\:{T}_{C}\), and STR denotes the PV power output (kW), PV temperature coefficient of power (%/°C), PV derating factor (\(\:\text{\%})\), the incident irradiance \(\:(\text{k}\text{W}/{\text{m}}^{2})\), PV cell temperature °C, and standard test conditions, respectively.

Diesel generator

DG is an energy system traditionally used to supply electricity in areas where grid connections are not viable. In HRES, the DG serves as a backup generator, operating during periods of power deficiency from RESs. This study considers a DG unit with a power capacity of 1 kW and an operational lifespan of 15,000 h to assess the overall performance of the proposed system. The fuel consumption for power generation is calculated as follows:

Where \(\:\varvec{F}\) represents the DG fuel intake (units/hr). \(\:{\varvec{F}}_{0,\varvec{D}\varvec{G}},\:{\varvec{F}}_{1,\varvec{D}\varvec{G}}\) are the fuel curve intercept coefficient (1.40 L/hr rated) and the fuel curve slope (0.236 L/hr/kW), respectively. YDG is the generator’s rated capacity (kW), and PDG is the generator’s power output (kW).

Power converter

The proposed system includes both AC and DC buses, requiring a reversible converter to ensure continuous electricity flow between them. The utilized converter functions as an inverter to convert DC to AC and as a rectifier to convert AC to DC. This study used a 1 kW converter with an estimated lifespan of 20 operating years, along with inverter and rectifier efficiencies of 95%. The power rating of the converter is evaluated using the following Equation:

where \(\:{\eta\:}_{con}\) and \(\:{P}_{peak}\) represents the converter efficiency and the peak load at the point of consumption, respectively.

Storage system

In HRES, various storage solutions, such as batteries, have been introduced to store electricity. However, batteries are limited by their short lifecycle, low charging autonomy, long charging times, and high emissions during manufacturing and disposal. PHES has emerged as a greener alternative, offering higher storage capacity by storing excess electricity as potential energy in water. This study examines the impact of integrating both systems on the performance of the proposed configuration.

Battery energy storage system

The BESS employed in this study is characterized by a nominal voltage rating of 12 V and an energy storage capacity of 1 kWh. The BESS serves a critical role in storing excess energy generated by the RE system, thereby enhancing the power supply’s overall reliability, stability, and operational efficiency, particularly during RE source unavailability. Moreover, it plays a significant role in mitigating fuel consumption, contributing to improved system sustainability. The maximum energy stored in a BESS can be practically determined by utilizing Eqs. (7–10) as follows: Eq. (7) represents the stored energy in the BESS over a given time frame. At the same time, Eq. (8) specifies the battery’s state of charge (SOC). As indicated by Eqs. (9) and (10), implementing SOC limits is recommended to maintain stability and prevent abrupt changes in the BESS’s SOC48.

where \(\:{E}_{ch}\)(t) denotes the energy input to the battery during charging at a specific time while \(\:{E}_{dch}\left(t\right)\) represents the energy output during discharging at the same moment. The parameters \(\:{\eta\:}_{dch}\) and \(\:{\eta\:}_{ch}\) correspond to the charging and discharging efficiencies of the battery, respectively, ensuring the processes are accurately modeled. The variables \(\:{E}_{dch}^{max}\) and \(\:{E}_{ch}^{max}\) define the upper operational limits for charging and discharging capacities. Furthermore, the binary variable \(\:{R}_{bat}\) is used to indicate the battery’s operational mode, where a value of 1 specifies charging activity and 0 indicates discharging activity during a given hour. \(\:{P}_{bat}\left(t\right)\) indicates the power variation at a particular time and, \(\:{B}_{nom}\) refers to the nominal storage capacity of the battery, serving as a key parameter in system design and analysis.

Pumped hydro energy storage

PHES stands out as one of the most reliable and efficient energy storage technologies, particularly in regions with abundant water resources. This system leverages the potential energy difference between two water reservoirs at varying elevations. During the charging cycle, surplus energy is used to pump water from the lower reservoir to the upper reservoir, effectively storing energy for later use. In the discharging cycle, this stored energy is harnessed by allowing the water to flow back to the lower reservoir, driving turbines to produce electricity through conventional hydropower processes. This study incorporates a PHES system with a capacity of 245 kWh to assess its feasibility compared to BESS. To effectively simulate both the pumping and power generation modes of operation, it is essential to accurately execute the power balance within the system, as described by the following Equation:

Where \(\:{P}_{B}\), \(\:{P}_{RE}\), and \(\:{P}_{L}\) represent the system’s power balance, the output power of the RE, and the consumed power, respectively.

The generation and pumping cycles are directly related to the \(\:{P}_{B}\) value, where the generation cycle corresponds to \(\:{P}_{B}<0\) and the pumping cycle corresponds to \(\:{P}_{B}>0\). The following Eqs. (12) and (13) represent the mathematical models used to determine the electrical power during the generation and pumping cycles, respectively49.

where \(\:{Q}_{disch}\left(t\right)\) represent the discharge flow rate, \(\:g\) is the gravitational acceleration, \(\:\rho\:\) is the water density. \(\:{\eta\:}_{T}\), \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}\), \(\:{\eta\:}_{pump}\) represent the efficiencies of the turbine, generator, and pump, respectively. \(\:\left({h}_{add}+{h}_{3}\right)\) represents the total head, which is used to determine the power output.

It is worth noting that the PHES system considered in this study features a reservoir capacity of 1000 m3, capable of discharging water over a 12 h period. With a practical head of 100 m and a generator efficiency of 90%, the system generates power at a rate of 20.4375 kW, yielding a total electrical energy output of 245.25 kWh during discharging. In reverse operation, the generator functions as a pump with the same efficiency. The calculated flow rate for the pump is 0.01875 m3/s, requiring 14.8 h to refill the reservoir. The total electrical energy required for pumping is 302.7 kWh, reflecting the system’s efficiency and overall performance.

Economic assessment

Before assessing the economic feasibility of the proposed configuration, it is crucial to evaluate the investment costs, including capital, replacement, and operation and maintenance expenses. These cost parameters are essential inputs for HOMER software to analyze the economic viability of each configuration effectively. The costs of PV, WT, DG, and storage systems were obtained from15. A detailed summary of the costs and specifications for the various components of the proposed system is presented in Table 2.

HOMER software serves as an advanced platform for evaluating the economic viability of hybrid energy systems, providing critical insights into the feasibility of proposed configurations. A comprehensive economic assessment forms a cornerstone of this evaluation, with HOMER quantifying key metrics such as LCOE, NPC, payback time (PBT), and return on investment (ROI). These parameters are instrumental in optimizing system design and ensuring cost-effective and sustainable energy solutions. The main Equation used for conducting the economic feasibility of the proposed configurations can be given as follows4:

Where \(\:TAC\), \(\:CRF\), \(\:TInvC\), \(\:LCT\), and \(\:{NC}_{i}\) represent the total annualized cost, capital recovery factor, total investment cost, life cycle time, and net cash flow in the year, respectively.

Environmental impact

Recently, implementing stand-alone systems to electrify isolated areas worldwide has become increasingly common and preferred, particularly in regions where extending the electrical grid is not feasible. However, environmental assessments have become crucial to demonstrating the efficiency and sustainability of energy systems, especially in African nations. Including multiple energy sources in the proposed hybrid system necessitates a comprehensive assessment of its environmental impact across various stages, including manufacturing, transportation, installation, operation and maintenance, and recycling. This section presents the mathematical equations used to evaluate both the emissions and the mitigated amounts of greenhouse gases over the life cycle of the proposed system. Equations (10) and (11) are employed to quantify the greenhouse gas emissions and the corresponding mitigated amounts, respectively50.

where \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{i}}\) represents the pollutant emission factor associated with the oil-based electricity production power plant. \(\:{\text{P}\text{E}}_{\text{i}}\) and \(\:{\text{P}\text{M}}_{\text{i}}\) denote the emitted and mitigated amounts of greenhouse gases, respectively. \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{y}}\) is the yearly energy production, and \(\:\text{C}\text{e}\text{x}\text{C}\) refers to the cumulative exergy consumption over the life cycle of the proposed HRES, which can be calculated as follows:

Where \(\:NPC\) is the net present cost of the proposed system, \(\:CE\) is the cost of electricity in Somalia.

In this study, the environmental benefits of the HRES are further evaluated by considering the CO2 credit (\(\:{\text{C}\text{R}\text{I}}_{{\text{C}\text{O}}_{2}})\), a parameter that incentivizes carbon emission reductions through financial mechanisms. Additionally, the carbon tax (\(\:{\text{C}\text{T}}_{{\text{C}\text{O}}_{2}})\), is analyzed as a complementary parameter to quantify the economic implications of emissions. Both \(\:{\text{C}\text{R}\text{I}}_{{\text{C}\text{O}}_{2}}\) and the \(\:{\text{C}\text{T}}_{{\text{C}\text{O}}_{2}}\) contribute to understanding the overall environmental and economic impact of the system. These two parameters can be estimated as following equation51:

where \(\:{\text{c}\text{r}\text{i}}_{{\text{C}\text{O}}_{2}}\) represents the carbon credit index, estimated at $20/ton, and \(\:{\text{c}\text{t}}_{{\text{C}\text{O}}_{2}}\) denotes the carbon tax rate in African countries, which is equivalent to $15/ton52,53.

The CO2 Payback Period (CO2 PBP) for the system is considered in the present study. This metric represents the time required for the system to offset the total CO2 emissions generated during its life cycle by replacing diesel-based power generation. Therefore, the CO2 PBP can be calculated as following:

Overall operating weather conditions

This study investigates a microgrid HRES incorporating a PV system and a WT, both of which depend on the availability of natural resources, namely solar and wind energy. A comprehensive evaluation of the proposed HRES necessitates an in-depth analysis of prevailing meteorological conditions to ensure optimal performance and reliability. While existing studies provide foundational insights, there remains a critical gap in the detailed assessment of localized weather patterns, particularly in understudied regions such as the Hobyo Seaport. This research leverages high-resolution meteorological data sourced from the NASA Power Project (https://power.larc.nasa.gov/)54, a globally recognized database, to conduct a precise and site-specific analysis. By referencing the exact geographical coordinates of the study area, this investigation not only bridges the gap in localized weather data but also establishes a robust framework for optimizing HRES design and deployment in similar coastal environments. This approach underscores the intersection of advanced meteorological analytics and renewable energy systems, offering a novel contribution to the field and paving the way for sustainable energy solutions in geographically unique locations. The results are presented in Fig. 4.

Figure 4 shows the overall weather conditions. As exhibited in Fig. 4a, the wind velocity varies throughout the year, with the maximum and minimum wind speeds recorded at approximately 11.85 m/s in July and 5.14 m/s in April, respectively. The average wind speed over the year is approximately 8.8 m/s, which is considered ideal for operating the WT at a higher power output. In terms of solar radiation, the data indicate a high radiation intensity throughout the year, with an average of 5.89 kWh/m²/d and an average clearness index of 59.13% (see Fig. 4b). This indicates that the location experiences favorable solar conditions for energy generation based on PV systems, with a consistent and substantial amount of solar radiation throughout the year. On the other hand, the selected location exhibits a suitable ambient temperature, with an average of 26.43 °C (see Fig. 4c). This indicates that the area has a moderate and stable ambient temperature, which is favorable for efficiently operating energy systems such as PV panels and WT. Stable temperatures help maintain system performance and reduce thermal stress on equipment, enhancing the overall reliability and efficiency of the microgrid. The weather conditions at Hobyo Seaport indicate excellent potential for RE implementation, with favorable wind speeds, high solar radiation, and a moderate, stable temperature, supporting the efficient operation of a HES.

Overall operating weather conditions for the selected location: (a) Wind speed, (b) Solar radiation, and (c) Ambient temperature54.

Energy management strategy

This study optimized energy system sizing using HOMER software, ensuring reliable power supply by meeting load demands through the load-following (LF) dispatch strategy. Recent studies, namely Bilal et al.55, have demonstrated the effectiveness of advanced energy management strategies in optimizing HRES, emphasizing real-time management and predictive maintenance. In this study, the LF dispatch strategy was employed due to its effectiveness in maximizing RE utilization and minimizing reliance on DGs. Unlike the cycle charging strategy, which operates DGs at full capacity, the LF strategy activates DGs only, when necessary, significantly reducing fuel consumption and operational costs. This approach is particularly beneficial for systems with high RE penetration, as it optimizes solar and wind energy usage while ensuring system reliability. By prioritizing primary loads, the LF strategy minimizes DG runtime and maintenance expenses, while enhancing the utilization of RE and energy storage systems. A 10% operational buffer was included for demand spikes or RE variability, with PV and wind turbines contributing 25% and 50% of total RE output, respectively. Simulations showed high reliability, with peak unmet energy at 0.0639% and annual capacity shortage at 0.0926%, demonstrating LF’s effectiveness in energy management.

Figure 5 illustrates the optimized HRES design with an integrated energy management strategy developed using HOMER Pro® software. The process includes modeling, optimization, simulation, and sensitivity analysis. The system components, PV panels, WT, storage system (SS), and a DG are configured to meet the load demand efficiently. The solar power output PPV(t) and WT generation EWT(t) are analyzed in comparison to the electric load demand (ELoad(t)). The PV and WT output is supplied to the load, and any excess electricity is stored in the storage system, provided it is not fully charged (SSSOC < SSSOC, max) with the excess electricity Eexcess (i.e., Pgen (t) \(\:\ge\:\) Pd), indicating that the generated power exceeds the power demand. When the storage system attains its maximum state of charge, the surplus energy is designated as the dump load and is allocated to fulfill the load demand. When EWT(t), PPV(t), and SS are insufficient to meet the load demand, and the demand surpasses the defined minimum load ratio, the DG is activated as a failsafe to provide the necessary power. However, when the power load demand (ELoad(t)) falls below the minimum load ratio required for DG activation and cannot be supplied by P(t) or the storage system, it results in an unmet load (PElec(t)) over the 20-year evaluation period. The optimization tool performs a comprehensive simulation of the HRES, determining the optimal system configuration to minimize the NPC while satisfying the load demand within predefined technical constraints. The simulation outcomes are then critically evaluated from technical, economic, and environmental perspectives, including the analysis of pollutant emissions throughout the full lifecycle time.

Results and discussion

This section evaluates the optimal HRES configuration for Hobyo Seaport by analyzing RE resource data and the community’s daily power requirements. Key factors assessed include RE potential, storage systems, and DG fuel availability, with a mathematical model iteratively refined to ensure feasibility. Four configurations (PV/WT/PHES, PV/WT/DG/PHES, PV/WT/DG/BESS, and WT/DG/PHES with a bidirectional converter), as detailed in Table 3, were simulated using HOMER Pro® to evaluate their technical, economic, and environmental performance. Key components such as PV panels, WT, DG, PHES, power converter, and BESS were optimally sized to meet peak load demands while adhering to system constraints. The configurations were ranked based on economic perspective and environmental metrics, including NPC, LCOE, initial capital, fuel costs, operational expenses, RE penetration, capacity shortages, surplus electricity, and CO2 emissions. Config. 1, comprising a PV/WT/PHES system with a power converter, emerged as the most effective, demonstrating superior technical and economic performance compared to Config. 2–4. This highlights its feasibility, reliability, and capacity to efficiently meet Hobyo Seaport’s energy requirements while minimizing costs and environmental impacts.

Performances evaluation of various configurations

The optimization results identify the optimal configuration of the microgrid HRES, including a PV capacity of 98 kW. This capacity was determined based on the suitability of the allocated area, which features a ground reflectance of 20%, making it conducive to installation and allowing for excess electricity generation to support adjacent Hobyo Searport facilities, such as small retail businesses surrounding the Seaports. For wind energy, an installed capacity of 140 kW was achieved through the deployment of 14 wind turbines, each with a rated capacity of 10 kW. HOMER’s selection of 14 turbines from a total of 28 available options reflects the high wind speeds at the site, emphasizing its strong potential for wind power generation. Furthermore, the HRES integrates a 280 kW DG as a backup power source. To ensure efficient energy storage, the system includes 796 strings of 1 kWh lead-acid batteries and 245 kWh pumped hydro storage, designed to store excess electricity generated by the PV and wind systems. Additionally, a bidirectional converter with a rated capacity of 225 kW was implemented to facilitate the conversion of power between DC and AC as required, ensuring operational flexibility and reliability. It should be noted that lead-acid batteries were chosen for their low cost and lower embodied energy compared to lithium-ion and flow batteries, making them suitable for cost-sensitive applications. However, a direct comparison with PHES is not appropriate, as PHES is designed for large-scale, long-duration energy storage, whereas lead-acid batteries are better suited for short-term storage and require higher maintenance. Given these fundamental differences, including other battery types in the comparison would be inconsistent.

The feasibility of PHES in a seaport context depends on the availability of elevation differences for water storage. While traditional PHES systems require significant altitude variations, alternative designs, such as coastal or underground PHES, enable deployment in flat terrains. This study primarily analyzes the feasibility of HPSS, but future research is needed to evaluate site-specific elevation data and explore potential modifications, such as utilizing man-made reservoirs or repurposing existing infrastructure. Additionally, seawater-based PHES, which has been successfully implemented in coastal regions, is considered a viable solution for such environments.

The system’s components were analyzed individually to evaluate performance. Figure 6 illustrates the monthly electricity production patterns (in MWh) for the four configurations, highlighting contributions from PV systems, WT, and DG. The annual electricity generation for ConFigs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 was 1130.86, 1130.94, 1217.56, and 781.97 MWh, respectively, successfully meeting all load demands with minimal capacity shortages.

In Fig. 6a, the energy production contributions for Config. 1 are shown, where PV systems and WT exclusively generate electricity. PV provided 46.7% of the total energy, while WT contributed 53.3%. This configuration achieved a 100% renewable energy fraction, with no DG usage. The monthly distribution demonstrates consistent WT production throughout the year, complementing the variability in PV output due to seasonal solar resource fluctuations. This configuration highlights the viability of achieving 100% renewable energy reliance, with PV and WT operating in harmony to ensure reliability. Figure 6b represents the energy production breakdown for Config. 2, which also achieves a 100% renewable energy fraction. Corresponding Config. 1, PV and WT systems dominate electricity generation, contributing 46.7% and 53.2%, respectively. A marginal DG usage of 84 kWh annually underscores its minimal role as a backup source during rare instances of insufficient renewable generation. The monthly breakdown mirrors Config. 1, with high WT output during the peak wind season (July) and balanced contributions from PV during sunnier months. This configuration demonstrates almost identical performance to Config. 1, emphasizing the robust potential of renewable energy systems. Figure 6c illustrates the energy production in Config. 3, where PV and WT contributions drop slightly to 42.7% and 49.5%, respectively. This configuration also incorporates DGs as a more significant contributor, providing 7.8% of the total energy (approximately 94,967 kWh annually). The inclusion of DGs reduced the renewable energy fraction to 87.3%. While WT still dominates electricity production, the increased DG usage highlights the system’s reliance on fossil fuels during periods of insufficient renewable generation. This configuration indicates the trade-offs between achieving higher reliability and maintaining lower environmental impact. Figure 6d displays the energy production in Config. 4, which relies predominantly on WT (77%) and DG (23%), with no PV contribution. This configuration produced the lowest annual electricity output (781.97 MWh) due to the absence of PV. DGs contributed significantly, generating 179,769 kWh annually, reducing the renewable energy fraction to 75.9%. The monthly breakdown shows higher DG activity in periods of lower WT production (e.g., April), underscoring its role in maintaining supply reliability. This configuration demonstrates a heavier dependence on fossil fuels compared to Configurations 1–3, emphasizing the critical role of PV and WT in reducing DG reliance.

Across all configurations, Fig. 6 highlights that WT consistently dominated electricity production, with varying contributions from PV systems and DG depending on the configuration. ConFigs. 1 and 2 achieved 100% renewable energy fractions, entirely minimizing DG reliance and demonstrating the potential for cost-effective and sustainable energy solutions with proper hybrid system design. Config. 3 introduced DG as a supplementary source, achieving an 87.3% RE fraction, while Config. 4 relied more heavily on DG, resulting in a lower RE fraction of 75.9%. Wind energy reliably supplied sufficient power throughout the year, minimizing capacity shortages in all configurations. The analysis underscores the critical importance of integrating energy storage systems and maximizing RE utilization to ensure cost-effective, reliable, and environmentally sustainable HRES designs while highlighting the need to optimize system components based on site-specific resource availability and demand profiles.

The operating hours of various components across four configurations of an HRES are summarized in Table 4. The PV system operates for 4318 h in Configs. 1, 2, and 3, excluded in Config. 4. The WT operates consistently for 8136 h across all configs., highlighting its importance as a primary energy source. The DG is absent in Config. 1, operates minimally for 1 h in Config. 2 and is utilized more extensively in Configs. 3 and 4, running for 1032 and 1911 h, respectively. The converter operates for 5273 h in Config. 1, with its runtime decreasing progressively to 3933 h in Config. 4, reflecting variations in system operation. These findings emphasize how the selected configuration determines component inclusion and operating hours.

The comparison of storage system autonomy across four configurations is summarized in Table 5. battery storage is utilized only in Config. 3, providing 5.62 h of autonomy, while Configs. 1, 2, and 4 excluded batteries. In contrast, PHES is employed in Configs. 1, 2, and 4, offering autonomies of 113, 119, and 266 h, respectively, whereas Config. 3 excludes this storage option.

Power curtailment refers to the percentage of generated energy that is not utilized due to oversupply, storage limitations, or grid constraints. It is typically calculated by dividing the excess electricity by the total power output of the system. In this study, power curtailment is considered to assess the feasibility of the proposed configuration, and the obtained results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6 presents the total, wind, and PV curtailment percentages for the four system configurations analyzed in HOMER. The results indicate significant variations in curtailment across the configurations, reflecting differences in system design, energy demand, and storage integration. Config. 3 exhibits the highest curtailment (37.34%), indicating significant excess energy due to oversizing or insufficient storage, while Configuration 4 has minimal curtailment (0.07%), suggesting a well-balanced system. Wind power curtailment is consistently higher than PV due to its greater share in total generation. In Configurations 1 and 2, total curtailment is around 28%, with wind and PV curtailments at ~ 15% and ~ 13%, respectively, highlighting the need for better energy utilization. To reduce curtailment, energy storage, load management, and optimized system sizing are crucial. Config. 4 demonstrates an effective design, while the high curtailment in other cases underscores the necessity for improved integration strategies.

Economic assessment of various configurations

This study evaluates the economic performance of four energy system configurations (Configs. 1–4) with a bidirectional converter, as detailed in Table 7. Key metrics, including capital investment, NPC, NPV, payback period, and LCOE, are analyzed to assess their financial performance. The configurations differ in integrating RE technologies and storage systems, providing insights into the trade-offs between initial investment and lifecycle benefits. The objective is to identify the most sustainable and economically viable solution for energy system design. The subsequent discussion provides a detailed comparison of these configurations based on the defined economic parameters.

The economic assessment of the four configurations (Configs. 1–4) highlights notable differences in financial viability and cost-effectiveness. Regarding capital investment, Config. 1 gain the lowest upfront cost at $348,277, followed by Config. 3 at $505,969, while Config. 4 necessitates the highest investment at $593,873. However, a lower initial investment does not necessarily equate to superior overall performance, as the subsequent metrics show. When evaluating the NPC, Config. 1 stands out with the lowest NPC of $619.72k, indicating tremendous cost efficiency over its lifecycle. Config. 2 shows a slightly higher NPC of $682k, while Config. 3 and Config. 4 exhibit significantly higher values at $4.29 M and $6.39 M, respectively. This pattern suggests that Config. 4’s reliance on WT, DG, and PHES with a bidirectional converter incurs substantial operational and maintenance costs, making it the least economical choice in terms of lifecycle costs. Correspondingly, Config. 1 and Config. 3 achieve the highest NPV at $25.5 M, demonstrating superior long-term economic benefits. Config. 4, on the other hand, records the lowest NPV at $19.8 M, further highlighting its limited profitability.

Annualized savings further reinforce the superior performance of Config. 1 and Config. 3 achieve $1.20 M in yearly cost reductions. Config. 2 follows closely with $1.04 M, while Config. 4 lags behind at $941,451, reflecting its inefficiency compared to the other configurations studied. Additionally, the payback period metric indicates that Config. 1 offers the quickest recovery of investment at 0.31 years, while Config. 4 requires the longest at 0.675 years. This disparity aligns with Config. 1’s robust financial returns, as it boasts the highest ROI of 339% and IRR of 330%. In contrast, Config. 4 records the lowest ROI (154%) and IRR (155%), highlighting its weaker financial performance. From the perspective of electricity generation costs, Config. 1 excels again with the lowest LCOE at $0.03845/kWh, making it the most cost-effective option. Config. 2 follows with a slightly higher LCOE of $0.04228/kWh, while Config. 3 and Config. 4 demonstrate considerably higher values at $0.2658/kWh and $0.3960/kWh, respectively. This indicates that Config. 4 has the highest lifecycle costs and strains to produce electricity efficiently. Notably, the LCOE of Config. 1 is lower than the most recently reported energy costs in the literature to some extent1,15,18,56,57.

Overall, Config. 1 (PV/WT/PHES with bidirectional converter) emerges as the most economically viable configuration, delivering the best performance across all metrics, including ROI, IRR, NPV, and LCOE, while maintaining a short payback period and high annualized savings. Config. 3 (PV/WT/DG/BESS with bidirectional converter) presents a balanced alternative, particularly in scenarios where advanced storage technologies like BESS are necessary. However, Config. 4 (WT/DG/PHES with bidirectional converter) performs poorly in almost all economic metrics, making it the least favourable adoption. Thus, Config. 1 is highly recommended for its superior overall economic performance, followed by Config. 3 as a viable option under specific technical requirements.

Cash flow for the current system and the proposed configuration

In this section, the cumulative cash flow (CCF) analysis, illustrated in Fig. 7, highlights significant cost differences between the current and the proposed systems over 20 years. The current system exhibits steadily increasing costs, culminating at $21,541,962.14 by the end of the project. This growth reflects the high operational and maintenance expenses associated with the existing configuration (only diesel generator). In contrast, the proposed systems, as depicted in Fig. 7, demonstrate substantial long-term cost savings, with each configuration delivering distinct financial benefits.

In Config. 1, the proposed system achieves the most dramatic savings, reducing CCF to $624,378.41, a 97.1% reduction compared to the current system. This configuration stands out for its minimal cash flow growth over time, as clearly shown in Fig. 7, indicating exceptional efficiency and cost control. Config. 2 also offers significant financial benefits, reducing cash flow to $3,695,786.02, an 82.85% reduction. While slightly less cost-effective than Config. 1, it balances substantial savings with potential system enhancements or resilience. Config. 3 ends with a CCF of $7,895,796.95, reflecting a 63.36% reduction compared to the current system. The higher cash flow trajectory, evident in Fig. 7, suggests potential trade-offs for enhanced performance, added features, or greater reliability. Config. 4 achieves a cumulative cash flow of $5,429,434.81, marking a 74.79% reduction. This configuration balances long-term savings with improved system capabilities, making it a competitive alternative to Config. 2.

The tendencies depicted in Fig. 7 emphasize the financial benefits of transitioning to the proposed systems. Config. 1 emerges as the most cost-effective option, followed by ConFigs. 2 and 4, and 3. The analysis underscores the importance of evaluating the cash flow trajectory of each configuration, as visualized in Fig. 7, to align with operational priorities and budgetary goals while achieving significant long-term cost reductions.

Environmental impact

In this section, the environmental impacts of various configurations are evaluated, and the results are presented in Table 8. As shown in Table 8, all configurations’ emissions over the LCT depend on the system components and their associated cumulative exergy consumption. Among the configurations, Config. 1 exhibits the lowest CO2 emissions over the LCT. This can be attributed to its reduced energy consumption during manufacturing, production, and end-of-life stages, primarily due to the absence of BESS and a DG. The config. 1 is responsible for emitting 531.7 tons of CO2, representing 90.85%, 14.45%, and 9.7% of the emissions from Configs. 2, 3, and 4, respectively. This lower CO2 emission positions Config. 1 as the least impactful in terms of GWP compared to the other configurations. Furthermore, the results indicate a lower CO2 emission per kWh of electricity produced in Config. 1 compared to the other configurations studied. Config. 1 emits only 17.9 gCO2/kWh, which is 4.9 gCO2, 106.3 gCO2, and 218 gCO2 lower than Configs. 2, 3, and 4, respectively. This demonstrates the superior environmental performance of Config. 1 with respect to carbon emissions per unit of electricity generated. The environmental benefits of the proposed HRES are further supported by recent studies (e.g. Bilal et al.58), which highlight the potential of hybrid energy systems to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and promote sustainability in coastal regions. Their findings align with the significant CO2 mitigation and carbon credit savings achieved by the PV/WT/PHES configuration in this study.

In this study, the carbon tax is considered based on an estimated index (i.e., $15/tons of CO2), as no specific carbon tax index is currently established for Africa, particularly in Somalia. Including the carbon tax as a factor highlights its potential benefits in reducing emissions by encouraging the adoption of cleaner technologies and energy-efficient practices. By internalizing the environmental costs associated with carbon emissions, the carbon tax serves as an economic incentive to lower greenhouse gas outputs, contributing to a more sustainable and environmentally conscious energy system. The obtained results are presented in Table 8.

The lower emission CO2 amount for the Config. 1 shows a lower carbon tax compared to the other configurations. The result shows that the Config. 1–4 over LCT are responsible of $7.97k, $8.78k, $55.21k, and $55.7k. This underscores the dual benefit of Config. 1, combining significant economic savings with a significantly lower environmental impact, making it the most sustainable and cost-effective choice among the configurations.

On the other hand, the environmental benefits of the proposed configuration are assessed in this section, and the results are presented in Table 8. Based on the data in Table 8, Config. 1 can be considered the most environmentally friendly compared to the other configurations. This is attributed to its higher mitigated CO2 emissions, amounting to approximately 1029.6 tons over one production year, which is equivalent to the avoided CO2 emissions of Config. 3. Furthermore, the avoided CO2 emissions of configs. 1 and 3 are 13.35% and 21.52% higher, respectively, compared to configs. 2 and 4. In terms of carbon credits, configs. 1 and 3 demonstrate a saving of $20.59k, which is $2.75k and $4.44k higher than the savings achieved by configs. 2 and 4, respectively.

The higher carbon mitigation achieved by Config. 1 and 3 ranks them as the most effective in reducing equivalent CO2 emissions in day-to-day commodities, as shown in Table 9. For instance, Table 8 demonstrates that the more significant CO2 mitigation in config.1 and 3 translates to avoiding the use of an equivalent of 190.48 cars, which is 13.33% and 21.3% higher than config. 2 and 4, respectively. Furthermore, the annual production of Config. 1 mitigates approximately 486.2 m³ of gasoline consumption, 2368.1 barrels of oil, 355.22 tons of waste recycling, and offsets about 226.52 acres of forest absorption.

In terms of the carbon payback period, the results indicate that Configuration 1 can offset the emitted CO2 over its lifespan in 0.52 years, which is 0.14, 3.06, and 6.27 years shorter than Configurations 2, 3, and 4, respectively. These findings demonstrate the higher feasibility of Configuration 1 compared to the other configurations.

To sum it up, based on the obtained performance results, Config. 1 can be considered the most suitable option in terms of lower environmental impact and higher benefits compared to the other configurations. This configuration demonstrates the feasibility of integrating hydro-pumped storage into the HRES system. Pumped hydro storage technology offers several advantages, particularly in terms of environmental and economic benefits. HRES systems based entirely on RE sources and pumped hydro storage can be regarded as a highly suitable approach to addressing the global environmental challenges posed by conventional energy resources, particularly in Somalia. However, several challenges must be addressed before the proposed system can be implemented in the Hobyo Seaport area. These include funding constraints, technological limitations, the availability of qualified personnel, and the infrastructure required for water storage systems.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of a HRES for powering Hobyo Seaport, Somalia, integrating PV, WT, and PHES. The study highlights the system’s potential to provide a sustainable, cost-effective, and reliable energy solution, contributing to improved energy security and environmental sustainability. In the following sections, the key findings, challenges, and future research directions are summarized.

-

The HRES integrating PV, WT, and PHES effectively meets the energy needs of Hobyo Seaport, Somalia.

-

The PV/WT/PHES configuration was identified as the optimal solution, offering outstanding economic, technical, and environmental performance.

-

The system demonstrates cost-effective energy production with a NPC of $619,720, a LCOE of $0.03845/kWh, and a simple payback period of 0.31 years.

-

The HRES achieves a 100% RE fraction, eliminating reliance on fossil fuels and reducing CO2 emissions by 1,029 tons annually, equivalent to $20,593 in carbon credits.

-

The integration of PHES extends energy storage autonomy to 113 h, improving system reliability and reducing environmental impact compared to conventional batteries.

-

Over a 20-year lifecycle, the system reduces cumulative cash flow by 97.1% compared to diesel-based generation, highlighting its long-term financial and operational benefits.

While the proposed system presents significant advantages, there are a few challenges and considerations that must be addressed for successful implementation and scalability.

-

High initial capital investment remains a barrier to widespread adoption of the HRES.

-

The need for skilled personnel for system maintenance and infrastructure development for water storage in PHES systems are operational challenges.

-

Logistical constraints in remote areas such as Hobyo, coupled with funding limitations, must be addressed for successful deployment and scalability.

The findings from this study pave the way for future research and development to enhance the performance and scalability of HRES in similar regions.

-

Future research could focus on integrating advanced energy storage solutions, such as hydrogen and next-generation batteries, to address intermittency and enhance storage capacity.

-

Assessing the impacts of climate change on RE resources will be crucial for designing more resilient and adaptable systems.

-

Further studies should explore socio-economic factors such as job creation, community engagement, and equitable energy access, especially in underserved regions.

-

Leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for optimized energy management could improve the efficiency and reliability of HRES.

-

Expanding the application of HRES to other critical infrastructure, particularly in coastal or remote regions, will support the scalability and sustainability of RE solutions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The custom MATLAB code used in this study, solely for plotting the results obtained from HOMER software, is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Al-Hanoot, A. K. et al. Distributed PV systems in Saudi Arabia: current status, challenges, and prospects. Energy Strategy Rev. 55 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2024.101535 (2024).

Energy Agency, I. & World Energy Outlook 2024. http://www.iea.org/terms (2024).

Napp, T. A. et al. The role of advanced demand-sector technologies and energy demand reduction in achieving ambitious carbon budgets. Appl. Energy. 238, 351–367 (2019).

Lekbir, A., Hassani, S. & Mekhilef, S. Techno-economic and life cycle assessment of a nanofluid-based concentrated Photovoltaic/Thermal-Thermoelectric hybrid system. J. Power Sources 595, (2024).

Lekbir, A., Zaoui, F., Khenfer, R., Tey, K. S. & Mekhilef, S. A comprehensive energy, exergy, economic, and environmental impact assessment of building-integrated photovoltaic systems. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-024-03099-0 (2024).

Global Energy Perspective 2023. (2023).

Energy agency, international. CO2 Emissions in 2022. http://www.iea.org (2022).

World Energy Transitions Outlook 2023. (International Renewable Energy Agency IRENA, 2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Renewable energy systems for Building heating, cooling and electricity production with thermal energy storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 165, (2022).

Hoseinzadeh, S., Astiaso Garcia, D. & Huang, L. Grid-connected renewable energy systems flexibility in Norway Islands’ decarbonization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 185, (2023).

Javed, M. S. et al. Impact of multi-annual renewable energy variability on the optimal sizing of off-grid systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 183, (2023).

Hüner, B. Feasibility and environmental analysis of biogas-based hybrid energy system using HOMER pro software: A case study for Hatay. Energy Convers. Manag 326, (2025).

Croce, L. F., Filho, T., Santos, G. L. & Barros, R. M. I. F. S. dos Attractivity analysis of hybrid energy generation based on current energy market scenarios in Brazil. Energy 318, (2025).

Gaurav, A., Tyagi, A., Jha, S. K. & Kumar, B. Feasibility analysis using MCDM techniques of hybrid energy systems powering healthcare facility on Island. Energy Convers. Manag 327, (2025).

Samatar, A. M., Mekhilef, S., Mokhlis, H., Kermadi, M. & Alshammari, O. Performance analysis of hybrid off-grid renewable energy systems for sustainable rural electrification. Energy Convers. Manag X 24, (2024).

Samatar, A. M., Mekhilef, S., Mokhlis, H., Kermadi, M. & Alshammari, O. Optimal design of a hybrid energy system considering techno-economic factors for off-grid electrification in remote areas. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-024-02939-3 (2024).

Kerboua, A., Hacene, F. B., Goosen, M. F. A. & Ribeiro, L. F. Development of technical economic analysis for optimal sizing of a hybrid power system: A case study of an industrial site in Tlemcen Algeria. Results Eng. 16, (2022).

Bouregba, H. et al. Feasibility study of a grid-connected PV/wind hybrid energy system for an urban dairy farm. Heliyon e40650 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e40650 (2024).

Kushwaha, P. K. & Bhattacharjee, C. Integrated techno-economic-environmental design of off-grid microgrid model for rural power supply in India. J. Inform. Optim. Sci. 43, 37–54 (2022).

Bilal, M., Bokoro, P. N. & Sharma, G. Hybrid optimization for sustainable design and sizing of standalone microgrids integrating renewable energy, diesel generators, and battery storage with environmental considerations. Results Eng. 25, (2025).

Yudhistira, R., Khatiwada, D. & Sanchez, F. A comparative life cycle assessment of lithium-ion and lead-acid batteries for grid energy storage. J. Clean. Prod. 358, (2022).

Ali, S., Stewart, R. A. & Sahin, O. Drivers and barriers to the deployment of pumped hydro energy storage applications: Systematic literature review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 5 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clet.2021.100281 (2021).

Psarros, G. N., Dratsas, P. A. & Papathanassiou, S. A. A comprehensive review of electricity storage applications in island systems. J. Energy Storage. 83 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.110658 (2024).

Pattnaik, A., Dauda, A. K. & Panda, A. Optimal utilization of clean energy and its impact on hybrid power systems incorporating STATCOM and pumped hydro storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 187, (2023).

Ma, T., Yang, H., Lu, L. & Peng, J. Optimal design of an autonomous solar-wind-pumped storage power supply system. Appl. Energy. 160, 728–736 (2015).

Yimen, N., Hamandjoda, O., Meva’a, L., Ndzana, B. & Nganhou, J. Analyzing of a photovoltaic/wind/biogas/pumped-hydro off-grid hybrid system for rural electrification in Sub-Saharan Africa - Case study of Djoundé in Northern Cameroon. Energies 11, (2018).

Jurasz, J., Dąbek, P. B., Kaźmierczak, B., Kies, A. & Wdowikowski, M. Large scale complementary solar and wind energy sources coupled with pumped-storage hydroelectricity for lower Silesia (Poland). Energy 161, 183–192 (2018).

Pali, B. S. & Vadhera, S. A novel solar photovoltaic system with pumped-water storage for continuous power at constant voltage. Energy Convers. Manag. 181, 133–142 (2019).

Liu, Z., Zhang, Z., Zhuo, R. & Wang, X. Optimal operation of independent regional power grid with multiple wind-solar-hydro-battery power. Appl. Energy. 235, 1541–1550 (2019).

Guezgouz, M. et al. Optimal hybrid pumped hydro-battery storage scheme for off-grid renewable energy systems. Energy Convers. Manag 199, (2019).

Samatar, A. M. et al. The utilization and potential of solar energy in Somalia: current state and prospects. Energy Strategy Reviews. 48, 101108 (2023).

Breyer, C. et al. On the history and future of 100 renewable energy systems research. IEEE Access. 10, 78176–78218 (2022).

Oubouch, N., Redouane, A., Makhoukh, A. & El Hasnaoui, A. Optimization and design to catalyze sustainable energy in Morocco’s Eastern Sahara: A hybrid energy system of PV/Wind/PHS for rural electrification. Clean. Energy Syst. 9, (2024).

Fan, J. & Zhou, X. Optimization of a hybrid solar/wind/storage system with bio-generator for a household by emerging metaheuristic optimization algorithm. J. Energy Storage 73, (2023).

Medghalchi, Z. & Taylan, O. A novel hybrid optimization framework for sizing renewable energy systems integrated with energy storage systems with solar photovoltaics, wind, battery and electrolyzer-fuel cell. Energy Convers. Manag 294, (2023).

Kharrich, M., Selim, A., Kamel, S. & Kim, J. An effective design of hybrid renewable energy system using an improved Archimedes optimization algorithm: A case study of Farafra, Egypt. Energy Convers. Manag 283, (2023).

Al Afif, R., Ayed, Y. & Maaitah, O. N. Feasibility and optimal sizing analysis of hybrid renewable energy systems: A case study of Al-Karak, Jordan. Renew. Energy. 204, 229–249 (2023).

Shabani, M., Dahlquist, E., Wallin, F. & Yan, J. Techno-economic comparison of optimal design of renewable-battery storage and renewable micro pumped hydro storage power supply systems: A case study in Sweden. Appl. Energy 279, (2020).

Zhang, Z., Wen, K. & Sun, W. Optimization and sustainability analysis of a hybrid diesel-solar-battery energy storage structure for zero energy buildings at various reliability conditions. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 55, (2023).

Roy, D. Modelling an off-grid hybrid renewable energy system to deliver electricity to a remote Indian Island. Energy Convers. Manag. 281, (2023).

Borba, A. T. A., Simões, L. J. M., de Melo, T. R. & Santos, A. Á. B. Techno-economic assessment of a hybrid renewable energy system for a County in the state of Bahia. Energies. 17, (2024).

Araoye, T. O., Ashigwuike, E. C., Mbunwe, M. J., Bakinson, O. I. & Ozue, T. G. I. Techno-economic modeling and optimal sizing of autonomous hybrid microgrid renewable energy system for rural electrification sustainability using HOMER and grasshopper optimization algorithm. Renew. Energy. 229, (2024).

Kelly, E. et al. Off grid PV/Diesel/Wind/Batteries energy system options for the electrification of isolated regions of Chad. Heliyon. 9, (2023).

Halabi, L. M., Mekhilef, S., Olatomiwa, L. & Hazelton, J. Performance analysis of hybrid pv/diesel/battery system using HOMER: A case study Sabah, Malaysia. Energy Convers. Manag. 144, 322–339 (2017).

Maleki, A. Optimization based on modified swarm intelligence techniques for a stand-alone hybrid photovoltaic/diesel/battery system. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 51, (2022).

Xu, X., Zhang, Z., Yuan, J. & Shao, J. Design and multi-objective comprehensive evaluation analysis of PV-WT-BG-Battery hybrid renewable energy systems in urban communities. Energy Convers. Manag. X 18, (2023).

Olatomiwa, L., Blanchard, R., Mekhilef, S. & Akinyele, D. Hybrid renewable energy supply for rural healthcare facilities: an approach to quality healthcare delivery. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 30, 121–138 (2018).

Iqbal, M. M. et al. Optimal scheduling of residential home appliances by considering energy storage and stochastically modelled photovoltaics in a grid exchange environment using hybrid grey Wolf genetic algorithm optimizer. Appl. Sci. 9, (2019).

Agajie, T. F. et al. Optimal design and mathematical modeling of hybrid solar PV–Biogas generator with energy storage power generation system in Multi-Objective function cases. Sustainability. 15, (2023).

Hassani, S., Saidur, R., Mekhilef, S. & Taylor, R. A. Environmental and exergy benefit of nanofluid-based hybrid PV/T systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 123, 431–444 (2016).

Khenfer, R. et al. Experimental investigation of water-based photovoltaic/thermal-thermoelectric hybrid system: energy, exergy, economic and environmental assessment. J. Power Sources 598, (2024).

Govinda, R. & Timilsina, S. E. R. D. W. B. W. D. Carbon Tax Design Architectures for Developing Countries. (2022).

World Bank. CARBON TAX GUIDE A Handbook for Policy Makers. (2017).

NASA Power Project. NASA Prediction of Worldwide Energy Resources. (2024).

Bilal, M., Bokoro, P. N., Sharma, G., Pau, G. A. & Cost-Effective Energy management approach for On-Grid charging of Plug-in electric vehicles integrated with hybrid renewable energy sources. Energies (Basel) 17, (2024).

Kushwaha, P. K. & Bhattacharjee, C. Socio-techno-economic-environmental sizing of hybrid renewable energy system using metaheuristic optimization approaches. Environ. Prog Sustain. Energy. 43, e14386 (2024).

Kushwaha, P. K., Ray, P. & Bhattacharjee, C. Optimal sizing of a hybrid renewable energy system: a socio-techno-economic-environmental perspective. J. Sol Energy Eng. 145, (2022).

Bilal, M., Ahmad, F., Mohammad, A. & Rizwan, M. Techno-economic evaluation and sensitivity analysis of renewable energy based designing of plug-in electric vehicle load considering load following strategy. Appl. Energy 377, (2025).

Sreenath, S., Sudhakar, K. & AF, Y. 7E analysis of a conceptual utility-scale land-based solar photovoltaic power plant. Energy 219, 119610 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the University of Technology Sydney and Universiti Malaya for their invaluable support in providing equipment and software licenses, which were integral to the success of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Abdullahi Mohamed Samatar & Abdelhak Lekbir: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Saad Mekhilef: Validation, Resources, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Hazlie Mokhlis: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Kok Soon Tey: Writing – review & editing. Abdullah Alassaf: Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Samatar, A.M., Lekbir, A., Mekhilef, S. et al. Techno-economic and environmental analysis of a fully renewable hybrid energy system for sustainable power infrastructure advancement. Sci Rep 15, 12140 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96401-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96401-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Techno-economic optimization of renewable hydrogen infrastructure via AI-based dynamic pricing

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Multi-objective metaheuristic optimization algorithm for hydropower plant structural stability

Asian Journal of Civil Engineering (2025)