Abstract

The time-dose reciprocity has long been a cornerstone in understanding ultraviolet (UV) sterilization. However, recent studies have demonstrated significant deviations from this law, attributed to complex mechanisms involving reactive oxygen species (ROS). This study investigates whether similar deviations occur at much shorter wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation than UV, specifically in the X-ray region, with a focus on the dose-rate dependence of bacterial inactivation. Using Escherichia coli as a model organism, it is found that dose-rate effects were highly dependent on the bacterial growth phase. In the stationary phase, lower dose rates with prolonged irradiation resulted in greater inactivation efficacy. The inactivation ratio obtained by the dose rate of 15.3 mGy/s shows more than 3 times larger than that obtained by the dose rate of 147 mGy/s at the dose of 200 Gy, which is consistent with findings from previous UV studies. On the other hand, in the exponential phase, higher dose rates with shorter irradiation durations were more effective. The inactivation ratio obtained by the dose rate of 147 mGy/s shows 40 times larger than that obtained by the dose rate of 15.3 mGy/s at the dose of 200 Gy. These results can be effectively explained by a stochastic multi-hit model that accounts for three terms of linearly proportional to dose, nonlinearly proportional to dose, and binary fission. This work bridges fundamental physical biology with practical applications, such as gamma sterilization, offering a robust framework for optimizing dose-rate strategies across diverse fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The principle of ultraviolet (UV) inactivation is traditionally described by the time-dose reciprocity (TDR) law: log(N/N0) = − Γ × DU, where Γ (cm2/mJ) is the inactivation rate constant, DU = IU × t, DU (mJ/cm2) is the UV dose, IU (mJ/s∙cm2) is the UV irradiance, and t (s) is the irradiation duration. This law has been widely applied to photoreaction processes, including photopolymerization, photoconductance, photodegradation, and UV sterilization1,2.

Recent studies indicate that UV inactivation shows significantly higher efficacy with lower irradiance and longer irradiation durations compared with higher irradiance and shorter durations at the same dose3,4. This effect, observed in Escherichia coli (E. coli), results in an inactivation ratio that is one to two orders of magnitude lower than expected under TDR-law assumptions3,4. Previous experiments have revealed that similar effects occur not only in E. coli but also in Bacillus subtilis spores5. This deviation from the TDR-law has been attributed to two mechanisms: (i) direct DNA damage (e.g., thymine dimer formation) from UV photon absorption, and (ii) indirect damage to DNA and/or proteins via reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during UV irradiation.

X-rays are physically the same type of electromagnetic radiation as UV radiation. However, at the higher photon energies compared to UV, electronic excitation becomes sufficient to eject absorbing electrons from their orbitals, resulting in molecular ionization6. This ionizing radiation induces DNA damage through both direct effects—ionization of bases and sugars7 and indirect effects—primarily through the generation of ROS in water8,9. For example, lower linear energy transfer (LET) radiation such as X-rays, the majority of DNA damage (~ 65%) is attributed to indirect effects, while direct effects account for the remaining approximately 35%8. While the biological effects of UV and X-rays are distinct, we consider that the inactivation mechanism, which involves both direct and indirect effects, could be understood in a unified physical framework.

This study investigates whether similar deviations occur under X-ray irradiation. To examine the TDR law in the X-ray region, experiments were conducted across an order of magnitude variation in dose rates (15 mGy/s ≤ P ≤ 150 mGy/s) under two conditions: (i) E. coli in saline solution (stationary phase) and (ii) E. coli in nutrient-rich agar culture (exponential phase), ensuring that a substantial change in dose rate could be applied. We demonstrate that the inactivation rate obtained by the experiments can be quantitatively described by three effects within a stochastic model10,11,12: (i) a term linearly proportional to dose, (ii) a term nonlinearly proportional to dose, and (iii) a replication term governed by binary fission in nutrient-rich environments. While the results and analyses presented here may not fully elucidate the microscopic DNA damage mechanisms induced by X-rays, they effectively capture various factors influencing X-ray inactivation in a simplified manner. The findings obtained here suggest that: (a) For gamma sterilization applications, where replication rates are negligible, lower dose rates and longer irradiation durations achieve more effective sterilization at the same total dose. (b) For therapeutic applications, where differences in replication rates are critical, higher dose rates and shorter irradiation durations are more effective.

Materials and methods

Culturing and counting of microorganisms

A culture of E. coli strain O1, which was kept at 4 °C, was incubated in nutrient broth (E-MC35; EIKEN Chemical Co., Japan) at 37 °C for 20 h. A concentration of approximately 1010 colony forming units (CFU)/mL was obtained and used for the experiments. The growth curve of E. coli O1 used in this experiment is provided in Supplemental information (Fig. S1). The overnight culture of E. coli was taken and diluted with a saline solution to approximately 105 CFU/mL. Inactivation experiments were performed under sterile conditions for two phases: (i) stationary phase, and (ii) exponential phase. (i) To perform the inactivation experiments of E. coli in the stationary phase, 1 mL of the dispersed solution was taken and injected into a microtube. The lifetime of E. coli in the stationary phase exceeds 12 h; therefore, no significant reduction in CFU was observed in the control samples before and after the series of experiments. After irradiating the microtube using an X-ray irradiation source, 100 µL of bacterial cells was taken and dispersed on agar plates (E-MC63; EIKEN Chemical Co., Japan). The plates were inverted and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. (ii) To perform the inactivation experiments of E. coli in the exponential phase, 0.1 mL of the dispersed solution was taken and dispersed on an agar plate. The plates were covered to prevent drying; therefore, no significant reduction in CFU was observed in the control plates before and after the series of experiments. We note that the plates remained covered during X-ray irradiation to prevent drying, using a 0.8 mm thick polyethylene cover, which ensured that 99% of the X-rays reached the plate13. After the irradiation of the agar plate using an X-ray irradiation source, the plate was inverted and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The E. coli colonies were counted to determine bacterial concentration. Log inactivation for E. coli was calculated as log (Ni/N0), where the bacterial concentration before and after irradiation were denoted as N0 and Ni, respectively.

X-ray irradiation

Irradiation was performed using a MXR226/22 X-ray source (Comet Yxlon GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) operated at an applied voltage of 220 kV and current of 10 mA with a beam-hardening aluminium filter. We performed five doses (D = 0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 Gy). These doses were determined based on previous E. coli inactivation experiments14,15,16. The dose rate was adjusted by the distance between the source and the E. coli sample. Three dose rates were prepared: PH = 147 × 10−3 Gy/s (Hereafter, we use 147 mGy/s), PM = 35.2 mGy/s, and PL = 15.3 mGy/s, where the dose rate was calibrated using a RAMTEC1000 dosimeter (Toyo Medic Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The energy spectrum of the X-ray source was characterized using a standard energy calibration method, ensuring consistent radiation quality across all experiments. All experiments were conducted in a temperature-controlled environment at 22 °C, with relative humidity maintained at 60%.

Statistical analysis

Aliquots were extracted and diluted in saline solution in 10-hold steps to ensure the colony count in the range of 30–300 CFU. Drop plating in triplicate was used for each run to determine the number of colonies. All experiments were performed at least three times independently. The data in the figures are presented as averages of CFU with error bars representing mean ± standard deviation. A two-tailed paired t-test statistical analyses were performed to determine the significance of the observed data at 95% confidence (p-values < 0.05).

Results

Dose dependence of stationary phase inactivation ratio at various dose rates

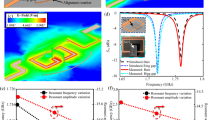

Figure 1a shows the inactivation ratio [Log(N/N0)] versus D at various dose rates. The red, green, and blue circles denote the inactivation ratios obtained by PH = 147 mGy/s, PM = 35.2 mGy/s, and PL = 15.3 mGy/s, respectively. The mean values of CFU and Log(CFU-ratio) are provided in Supplemental information (Table S1). It is found that decreasing the dose rate increased the inactivation ratio. At D = 200 Gy, the inactivation ratio obtained by PL was approximately 1.6 times higher than that obtained by PM (p-value = 0.015) and 3.1 times higher than that obtained by PH (p-value = 0.007). The observed inactivation curves exhibit shoulders followed by linear slopes, indicative of a multi-target inactivation process, where bacterial cells are inactivated by hits on multiple critical targets10,11,12. However, the differences in inactivation ratios across dose rates cannot be fully explained using standard target theory alone. A more comprehensive explanation requires incorporating nonlinear effects. The present dose-dependent experiments do not provide sufficient evidence to determine the origin of the nonlinear effects; however, we consider ROS to be responsible for this phenomenon3,4. Because, at higher dose rates, ROS concentrations increase rapidly, increasing the likelihood of ROS interacting and destroying each other before they can inflict biological damage. Conversely, at lower dose rates, ROS are produced more gradually, reducing the risk of mutual destruction and enhancing their damaging effects on cellular macromolecules. In the following section, we quantitatively analyze this phenomenon by introducing the nonlinear term into a stochastic theory framework, providing a detailed explanation of the dose rate dependence observed in the stationary phase.

(a) Inactivation ratio of E. coli O1 in the stationary phase as a function of dose for dose rates of 147 mGy/s (red circles), 35.2 mGy/s (green circles), and 15.3 mGy/s (blue circles). Solid lines represent theoretical fits obtained using the stochastic model with parameters: \(\small {{\Gamma }}_{0}=3.3\times {10}^{-2}\)(Gy−1), \(\small {{\Gamma }}_{1}=1.0\times {10}^{-3}\) (Gy−1/2s−1/2), and \(\small {{\Gamma }}_{2}=0\) (s−1). (b) Inactivation ratio as a function of irradiation duration. Red, green, and blue markers indicate inactivation ratios for dose rates of 147 mGy/s, 35.2 mGy/s, and 15.3 mGy/s, respectively. Solid triangles, rhombuses, squares, and circles denote results for doses of 50 Gy, 100 Gy, 150 Gy, and 200 Gy, respectively. Broken lines represent theoretical curves as a function of irradiation duration derived from Eq. (11) for P = 147 mGy/s (red), 35.2 mGy/s (green), and 15.3 mGy/s (blue). Dotted-dash lines represent theoretical curves for D = 50 Gy (purple), 100 Gy (blue), 150 Gy (green), and 200 Gy (red). Intersections between broken lines and dotted-dash lines correspond to the theoretically evaluated inactivation ratios.

Dose dependence of exponential phase inactivation ratio at various dose rates

Figure 2a shows the inactivation ratio [Log(N/N0)] versus D at various dose rates. Red, green, and blue circles denote the inactivation ratios obtained by PH = 147 mGy/s, PM = 35.2 mGy/s, and PL = 15.3 mGy/s, respectively. The mean values of CFU and Log(CFU-ratio) are provided in Supplemental information (Table S1). In contrast to the stationary phase results, decreasing the dose rate resulted in a lower inactivation ratio; thus, the exponential phase experiments showed the opposite trend. Notably, irradiation at the lowest dose rate (PL) exhibited minimal inactivation, even at a high dose of 200 Gy, compared with the significant inactivation observed with the highest dose rate (PH). Interestingly, the inactivation efficacy achieved with the highest dose rate (PH) is comparable between the exponential and stationary phases. At D = 200 Gy, the inactivation ratio for PH is approximately seven times larger than that for PM (p-value = 0.025) and 40 times larger than that for PL (p-value = 0.005). This behavior can be explained by considering two competing processes during the exponential phase: (a) Inactivation by X-ray irradiation: As in the stationary phase, dose dependent cellular damage with the nonlinear effect occurs. (b) Replication by binary fission: During the exponential phase, bacteria actively divide in the nutrient-rich agar. At lower dose rates, the replication rate may offset or exceed the inactivation rate, leading to reduced efficacy. These results suggest that the combined effects of inactivation and replication dynamics are critical to understanding dose-rate dependence in the exponential phase. In the following section, we present a more detailed quantitative analysis by incorporating the replication term into the stochastic theory.

Inactivation ratio of E. coli O1 in the exponential phase as a function of dose for dose rates of 147 mGy/s (red circles), 35.2 mGy/s (green circles), and 15.3 mGy/s (blue circles). (a) Solid lines represent the theoretical fits obtained with the nonlinear mutual destruction term, using parameters \(\small {{\Gamma }}_{0}=3.3\times {10}^{-2}\)(Gy−1), \(\small {{\Gamma }}_{1}=1.0\times {10}^{-3}\) (Gy−1/2s−1/2), and \(\small {{\Gamma }}_{2}=6.7\times {10}^{-4}\) (s−1). (b) Broken lines are the theoretical fits without the nonlinear mutual destruction term, using parameters \(\small {{\Gamma }}_{0}=3.3\times {10}^{-2}\)(Gy−1) and \(\small {{\Gamma }}_{2}=4.7\times {10}^{-4}\) (s−1).

Analysis

Stochastic modeling of X-ray inactivation dynamics

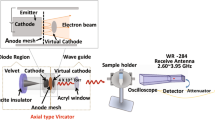

The inactivation of bacteria by X-ray irradiation occurs through stochastic hits on critical targets within the cells17,18,19. A schematic representation of this process is shown in Fig. 3a. During irradiation of duration t, the number of bacteria Nij(t) is defined as those with i total targets, j of which are hit. The parameters of λj, µj, and ν1 denote the hit rate, recovery rate, and replication rate, respectively. Based on these definitions, the dynamics of Nij(t) can be described by the following differential equations:

(a) Stochastic model in which the inactivation occurs by the hit of targets. Nij (t) is the number of bacteria where j targets are hit on the total number of i targets. λj, µj, and ν1 represent the hit rate, recovery rate, and replication rate, respectively. (b) Schematic of DNA inactivation. Γ0 represents the rate of linearly dose rate dependent term, Γ1 is the rate of the nonlinearly dose rate dependent term, and Γ2 is the rate of replication by binary fission at the Nij (t) state.

The hit rate λj is expressed as the proportion of non-hit targets to the total number of targets:

It is known that ROS at high densities undergo mutual destruction, which enhances the inactivation effect at lower dose rates3,4,20; therefore, we consider that ROS is responsible for the nonlinear effect. Figure 3b schematically illustrates the following three key processes influencing DNA inactivation during X-ray irradiation: (i) Dose-proportional term (Γ0Pt): Linearly proportional to the dose rate. (ii) Nonlinear mutual destruction term (\(\small {\Gamma _1}\sqrt P t\)): Accounts for the saturation effect for higher dose rate, modeled as \(\small \sqrt P\) based on previous studies3,4. (iii) Replication by binary fission term (Γ2t): Reflects bacterial replication in nutrient-enriched conditions, independent of dose rate. This framework integrates physical and biological mechanisms, providing a unified explanation for the observed dose-rate dependencies across both stationary and exponential phases.

Based on these considerations, the hit rate λ0 and replication rate ν1 can be expressed as:

and

A simplified multi-target model is adopted based on previous studies17,18,19, where the recovery rate μj is assumed to be negligible compared with λ0 and ν1. Thus, μj is excluded from further calculations.

To describe the observed shoulder behavior followed by linear slopes (Figs. 1a and 2a), we employ a simple two-target model where bacterial cells are inactivated by hits on two critical targets. The inactivation ratio I is expressed as the sum of non-hit (N20) and single-hit (N21) targets:

where N0 is the initial number of bacteria. This sum is obtained by solving Eqs. (1) and (2) in matrix form:

The solution is derived using eigenvalues. Substituting Eqs. (5) and (6) into the results yields the number of bacteria in non-hit (N20) and single-hit (N21) states as functions of irradiation duration:

Substituting Eqs. (9) and (10) into Eq. (7), the inactivation ratio I as a function of dose D is expressed as:

This equation successfully describes both the shoulder behavior followed by linear slopes and the dose rate dependence of the inactivation ratio observed in Figs. 1a and 2a.

Stationary phase analysis

Figure 1a shows the inactivation ratio of E. coli in the stationary phase across varying dose rates (PH = 147 mGy/s: red, PM = 35.2 mGy/s: green, PL = 15.3 mGy/s: blue). The data reveal that lower dose rates (PL) result in significantly higher inactivation efficacy compared with higher dose rates (PH), particularly at doses above 100 Gy. This trend is attributed to the nonlinear effect. The theoretical curves (solid lines) derived from the stochastic multi-hit model incorporating the nonlinear effect described by Eq. (11) using the parameters: Γ0 = 3.3 × 10−2 (Gy−1), Γ1 = 1.0 × 10−3 (Gy−1/2 s−1/2), and Γ2 = 0 (s−1), align closely with the experimental data, validating the model’s ability to capture key mechanistic behaviors.

A more detailed analysis of the dose-rate dependence of the inactivation ratio can be achieved by separating the dose into its components: dose rate and irradiation duration. Figure 1b demonstrates the dependency of the inactivation ratio on irradiation duration for varying dose rates. Here, red, green, and blue markers represent the inactivation ratios corresponding to dose rates of PH = 147 mGy/s, PM = 35.2 mGy/s, and PL = 15.3 mGy/s; and solid triangles, rhombuses, squares, and circles denote inactivation ratios for doses of 50 Gy, 100 Gy, 150 Gy, and 200 Gy, respectively. These curves were generated using the same parameters (Γ0, Γ1, and Γ2) across all conditions, with intersections between the broken and dotted-dash lines representing the theoretically evaluated inactivation ratios. The agreement between the intersections of the theoretical curves (broken and dotted-dash lines) and the experimental data provides quantitative support for the model parameters used, further highlighting the dose-rate sensitivity in stationary-phase E. coli. The stochastic model expressed in Eq. (11) provides a good fit to the observed behavior of the inactivation ratio as a function of dose rate. A slight discrepancy between the theoretical and experimental results at 50 Gy is noted. The minor discrepancies at D = 50 Gy likely arise from the assumptions of two targets and/or the elimination of additional mechanisms, such as the recovery rate of µj, which may not fully capture the complexity of the system at lower doses.

Exponential phase analysis

Figure 2a shows the inactivation ratio of E. coli in the exponential phase under varying dose rates. In contrast to the stationary phase, higher dose rates (PH) yield significantly greater inactivation efficacy. This phase-dependent reversal is explained by the interplay between the nonlinear effect and bacterial replication dynamics. At lower dose rates (PL), the replication rate outpaces inactivation, resulting in diminished efficacy. The theoretical curves (solid lines), derived from the model incorporating both nonlinear dynamics and replication, accurately capture these complex behaviors, underscoring the critical role of bacterial replication in shaping dose-rate dependence. Here the theoretical curves were fitted using: Γ2 = 6.7 × 10−4 (s−1), which corresponds to a replication time of approximately 25 min, consistent with the replication rate of E. coli at room temperature, and the other parameters, Γ0 and Γ1, remain unchanged. The model successfully explains the exponential phase behaviors, where the replication term (Γ2t) offsets inactivation effects at lower dose rates, resulting in reduced efficacy.

Notably, if the nonlinear mutual destruction term (\(\small {\Gamma _1}\sqrt P t\)) is excluded, the experimental results for the exponential phase can still be fitted, albeit with a slightly adjusted replication rate: Γ2 = 4.7 × 10−4 (s−1) (Γ1, remain unchanged), as shown in Fig. 2b. Under these conditions, the dose rates of PH = 147 mGy/s (red line) and PM = 35.2 mGy/s (green line) align well with the model. However, the exclusion of the mutual destruction term fails to explain the reduction in inactivation efficacy observed at doses above 150 Gy for PL = 15.3 mGy/s (blue line). This underscores the critical role of the nonlinear effect at lower dose rates in shaping the inactivation dynamics.

Discussion

Transition between dose rate effectiveness based on replication rates

The results demonstrate that the inactivation ratio is significantly influenced by replication rates at lower dose rates, whereas higher dose rates are unaffected by replication dynamics. Figure 4 shows 3D plots of the theoretical inactivation ratios given by Eq. (11) as a function of replication terms (\(\small 0 \leqslant {\Gamma _2} \leqslant 2.0 \times {10^{ - 4}}\); Γ0, Γ1 remain unchanged) for various dose rates. The red, green, and blue meshes correspond to the dose rates PL, PM, and PH, respectively. The boundaries defining the effectiveness of dose rates are indicated by the curves XL1 (broken grey line), XL2 (solid line), and XL3 (dotted broken grey line). These boundaries are determined by the following equation:

3D plots of the theoretical inactivation ratios as a function of replication terms (0 ≤ Γ2 ≤ 2.0 × 10−4) for various dose rates. The red, green, and blue meshes correspond to dose rates PL, PM, and PH, respectively. The boundaries defining the effectiveness of dose rates are indicated by the curves XL1 (broken grey line), XL2 (solid line), and XL3 (dotted broken grey line).

where the XL1 curve is derived by substituting Pi = PM and Pj = PL into Eq. (12). Similarly, the XL2 and XL3 curves are obtained by applying analogous substitutions for other dose rate combinations. The boundary curves XL1, XL2, and XL3 are obtained from Γ2 = 7.45 × 10−5, 9.35 × 10−5, and 1.26 × 10−4 (s−1), respectively. Below these boundary curves (Γ2 < XL1, XL2, XL3), a lower dose rate is more effective for inactivation due to reduced replication effects. Conversely, for Γ2 above these boundaries, a higher dose rate becomes more effective, as the replication rate dominates and offsets the inactivation process.

Implications for gamma sterilization

(a) Nutrient-poor Materials: For applications such as sterilizing medical equipment, where nutrient-rich environments are unnecessary, lower dose rates with longer durations can achieve equivalent inactivation ratios with smaller total doses. This approach is more energy-efficient and effective. (b) Nutrient-rich Materials: For biological products or fresh foods, replication plays a minimal role when using higher dose rates and shorter durations. Consequently, higher dose rates provide a more effective strategy for sterilization in such environments.

Limitations

This study investigated the dose-rate dependence of single high-dose X-ray irradiation on E. coli, revealing distinct inactivation behaviors between stationary and exponential phases. However, certain limitations must be acknowledged. Fundamental mechanisms, such as DNA repair, play a crucial role in bacterial survival, and these processes are closely linked to the growth phase. In this case, ROS and/or reactive nitrogen species (RNS) influence the initiation of specific repair pathways, where they function as signalling molecules20,21,22. However, these considerations are not included in this study.

Furthermore, we consider ROS and/or RNS to be responsible for the nonlinear effect. Because, at higher dose rates, ROS/RNS concentrations are expected to increase rapidly, raising the likelihood of their interactions leading to mutual destruction before they can inflict biological damage. This nonlinear effect is more pronounced in long-lived molecules with lifetimes exceeding 10−3 s, and it is likely that superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and nitric monoxide (NO) contribute to this mechanism9,23,24,25. Interpreting the inactivation behaviors observed in this study using a stochastic model with a nonlinear term may risk oversimplifying the above radiation-induced damage effects. Future studies incorporating real-time ROS/RNS detection, lifetime determination of ROS/RNS, and/or scavenger experiments are needed to further validate these findings.

Conclusion

This study found significant differences in E. coli inactivation efficacy under the same dose but with varying dose rates and irradiation durations using 220 keV X-rays. For stationary phase experiments, higher inactivation efficacy was observed at lower dose rates with longer irradiation durations than higher dose rates with shorter durations. On the other hand, in exponential phase experiments, higher inactivation efficacy was achieved at higher dose rates with shorter irradiation durations. These results were effectively explained using a stochastic model that incorporates nonlinear effects. The origin of nonlinear effects is likely due to long-lived ROS/RNS such as superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide and NO. However, the precise mechanism underlying these nonlinear effects warrants further investigation. Although the findings were derived from basic experiments with E. coli, this research provides foundational knowledge that can inform the optimization of sterilization protocols and radiotherapy techniques, particularly in applications requiring precise control of dose rate and duration.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bunsen, R. W. & Roscoe, H. E. Photochemical researches–Part V. On the measurement of the chemical action of direct and diffuse sunlight. Proc. R. Soc. 12, 306–312 (1862).

Wydra, J. W., Cramer, N. B., Stansbury, J. W. & Bowman, C. N. The reciprocity law concerning light dose–relationships applied to BisGMA/TEGDMA photopolymers: Theoretical analysis and experimental characterization. Dent. Mater. 30, 605–612 (2014).

Pousty, D., Hofmann, R., Gerchman, Y. & Mamane, H. Wavelength-dependent time–dose reciprocity and stress mechanism for UV-LED disinfection of Escherichia coli. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 217, 112129 (2021).

Matsumoto, T., Tatsuno, I., Yoshida, Y., Tomita, M. & Hasegawa, T. Time-dose reciprocity mechanism for the inactivation of Escherichia coli explained by a stochastic process with two inactivation effects. Sci. Rep. 12, 22588 (2022).

Sommer, R., Haider, T., Cabaj, A., Pribil, W. & Lhotsky, M. Time dose reciprocity in UV disinfection of water. Water Sci. Technol. 38, 145–150 (1998).

von Songtag, C. The Chemical Basis of Radiation Biology (Taylor & Francis, 1987).

Ward, J. F. DNA damage produced by ionizing radiation in mammalian cells: Identities, mechanisms of formation and reparability. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 35, 95–125 (1988).

Friedberg, E. C. et al. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis 2nd edn (ASM Press, 2006).

Riley, P. A. Free radicals in biology: Oxidative stress and the effects of ionizing radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 65, 27–33 (1994).

Atwood, K. C. & Norman, A. On the interpretation of multi-hit survival curves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 35, 696–709 (1949).

Luria, S. E. & Dulbecco, R. Genetic recombinations leading to production of active bacteriophage from ultraviolet inactivated bacteriophage particles. Genetics 34, 93–125 (1949).

Puck, T. T. & Marcus, P. I. Action of X-rays on mammalian cells. J. Exp. Med. 103, 653–666 (1956).

NIST PHYSICAL MEASUREMENT LABORATORY. https://physics.nist.gov/PhysRefData/Xcom/html/xcom1.html

Howard-Flanders, P., Theriot, L. & Stedeford, J. B. Some properties of excision-defective recombination-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 97, 134–141 (1969).

Zhang, H., Ha, T. M. H., Seck, H. L. & Zhou, W. Food Cont. 110, 107031 (2020).

Cha, M. Y. & Ha, J. W. Low-energy X-ray irradiation effectively inactivates major foodborne pathogen biofilms on various food contact surfaces. Food Microbiol. 106, 104054 (2022).

Zhao, L., Mi, D., Hu, B. & Sun, Y. A generalized target theory and its applications. Sci. Rep. 5, 14568 (2015).

Ballarini, F. From DNA radiation damage to cell death: Theoretical approaches. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 350608 (2010).

Lea, D. E. Actions of Radiations on Living Cells, 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, New York (1955).

Halliwell, B. & Gutteridge, J. M. C. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine 5th edn (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Chatterjee, N. & Walker, G. C. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair and mutagenesis. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 58, 235–263 (2017).

Portess, D. I., Bauer, G., Hill, M. A. & O’Neill, P. Low-dose irradiation of nontransformed cells stimulates the selective removal of precancerous cells via intercellular induction of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 67, 1246–1253 (2007).

Schmitt, F. et al. Reactive oxygen species: Re-evaluation of generation, monitoring and role in stress-signaling in phototrophic organisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837, 835–848 (2014).

Diaz, J. M. & Plummer, S. Production of extracellular reactive oxygen species by phytoplankton: Past and future directions. J. Plankton Res. 40, 655–666 (2018).

Thomas, D. D., Liu, X., Kantrow, S. P. & Lancaster, J. R. Jr. The biological lifetime of nitric oxide: Implications for the perivascular dynamics of NO and O2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 98, 355–360 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to thank Dr. Masanori Isaka and Dr. Hideyuki Matsui for information about bacterial handling techniques. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 24K02406 and a Grant-in-Aid for Research at Nagoya City University (Grant Number 2321102).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: T.M. is the first author. K.M., A.H., and H.I. contributed to the design of the X-ray inactivation system; K.M., I.T., and C.S. performed the E. coli X-ray inactivation experiments; and I.T. and T.H. provided technical support and bacterial expertise for bacterial growth techniques. T.M., H.I., and M.T. constructed and analysed the quantitative model that describes the difference in inactivation efficacy versus dose rate at the same dose. A.H. and T.H supervised the X-ray inactivation experiments. All authors read and approved this submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsumoto, T., Matsumoto, K., Tatsuno, I. et al. Time-dose reciprocity mechanism for the inactivation of Escherichia coli using X-ray irradiation. Sci Rep 15, 14803 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96461-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96461-1