Abstract

The correlation between sound and psychophysiological health is complex. This study explores effects of various sound pressure levels (SPLs) on psychophysiological responses, utilizing dynamic features of neural activity. Two sound types (traffic noise and spring water sound) and five SPLs (40, 45, 50, 55, and 60 dBA) were tested, with no sound serving as the control condition. The electrocardiography (ECG) and electroencephalogram (EEG) of 38 young college students were collected. The results indicate that spring water sound (SWS) significantly enhances sound perception, with sound comfort votes (SCV) and sound pleasure votes (SPV) increasing by 0.10–0.95 and 0.05–1.10, respectively. SWS facilitated parasympathetic nervous system comfort. Compared to the no sound, as SPLs increased, LF/HF decreased (by 0.07–0.41), and SDNN increased (by 8.85–18.56 ms), whereas traffic noise (TN) exhibited the opposite trend. For brain oscillatory activity, α, θ, and β power—associated with stress recovery—initially increased and then decreased with rising SPLs under spring water sound exposure. At 50 dBA SWS, effective delay duration, linked to comfort, peaked at 284.78 ms. Conversely, the α power and τe for TN diminished with increasing SPLs. The left frontal-parietal and right occipital lobes exhibited the highest sensitivity (p < 0.01). SWS exposure reduced the avalanche critical index (ACI) by 4.78–17.29% compared to no sound, enhancing brain comfort, while TN increased the ACI by 2.28–29.37%. The 50 dBA SWS showed the greatest improvement in brain comfort, being 1.74 times higher than that of TN. Furthermore, compared to no sound, brain power loss was lower for 52.63–63.16% of participants exposed to 50–60 dBA SWS. This study provides a methodology for soundscape evaluation and enhances understanding of how brain activity changes under sound exposure can improve the indoor acoustic environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The acceleration of urbanization has led to increased indoor activity, simultaneously escalating psychological stress. Consequently, enhancing indoor environment quality has become central to research on healthy living spaces. While the visual aspects of environments often receive attention, the acoustic environment, particularly crucial for those spending extended periods indoors working or studying, frequently goes neglected1. Increasing evidence suggests that noise exposure can adversely affect psychophysiological health, causing issues such as hearing loss, depression, and diminished concentration2,3,4. A high-quality acoustic environment can facilitate recovery, thus improving environmental quality and well-being5. Comprehending the mechanisms by which acoustic environments influence individual psychophysiological responses is essential for optimizing indoor acoustic conditions.

Sound type and sound pressure level (SPL) are crucial variables in studying indoor acoustic environments. Sound types can be categorized by source into artificial, active, and natural sounds, and by impact into negative noise and positive sound. Research indicates that artificial and active sounds, such as traffic noise (TN), and conversational noise, predominantly constitute negative noises that disrupt concentration and impair work performance6. Cohen et al.7 and Schlittmeier et al.8 found that noise exposure leads to increased anxiety and stress, whereas music and natural sounds have a restorative effect. Kallinen et al.9 discovered that fast-paced music helps increase alertness. Alvarsson et al.10 found that natural sounds, such as spring water sound (SWS) and bird song, aid in stress recovery. Guan et al.11 and Yang et al.12 also reported similar results. TN and SWS are common types of sounds. Most research has demonstrated that different sound types have distinct effects on psychophysiological responses. TN has been shown to increase stress and anxiety6, whereas natural sounds promote relaxation and recovery10. TN is one of the most common environmental noise sources, widely present in residential areas, schools, and other spaces8, and its negative effects have been well-documented. In contrast, SWS is a typical natural sound that has been recognized in environmental psychology and soundscape studies for its restorative effects13. This study aims to explores the impact of sound on psychophysiological comfort by comparing negative and positive auditory stimuli. This study examines how sound influences psychophysiological comfort by contrasting positive and negative auditory stimuli. Therefore, TN and SWS were selected as the experimental sound conditions. Besides the type of sound, SPL also affects individuals’ psychophysiological responses. Pierrette et al.14 reported a significant correlation between the degree of annoyance and SPL. Some studies have considered both the type of sound and SPL on individuals (see Table 1). Yang et al.12 found that different types of sounds (noisy sounds, fan sounds, music, and water sounds) and various SPLs (45, 55, 65, and 75 dBA) significantly affect subjective comfort, with water sounds having a positive effect. Meng et al.15 found that the interference effect increases when TN rises from 50 to 65 dBA. Several studies have examined the masking effect of SWS at different SPLs on noise. Hong et al.16 explored how adding SWS at varying SPLs influences soundscape quality and examined the related psychoacoustic characteristics. Yang et al.17 investigated the influence of 35, 40, 45, and 50 dBA SWS on noise perception through subjective evaluations of both unpleasant and pleasant emotions. Cai et al.18 found that when the SPL of SWS (fountain sounds) matches industrial noise, it is most effective in minimizing perceived annoyance. Similarly, Jeon et al.19 reported that SWS enhance soundscape quality, particularly when their SPL is close to or at least 3 dB higher than the noise level. The 40–60 dBA range closely aligns with typical SPLs in daily life. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that nighttime noise in residential areas should not exceed 45 dBA to ensure good sleep quality. The European Union Environmental Noise Guidelines suggest that daytime noise should be ≤ 55 dBA, as levels exceeding 55 dBA may pose health risks, such as an increased likelihood of cardiovascular diseases20. China’s Environmental Quality Standard for Noise (GB 3096 − 2008) specifies that nighttime noise in quiet residential areas should not exceed 40 dBA. Noise levels below 40 dBA may have negligible effects21, whereas exposure to 60 dBA and above may increase anxiety, with its negative impact widely discussed15. To better identify the key thresholds for sound comfort and pleasure, this study analyzes five sound pressure levels: 40, 45, 50, 55, and 60 dBA. However, these studies rarely incorporate psychophysiological measurements. Existing research primarily explores two areas: the effects of different sounds on emotions and behavior, and the masking impact of SWS on noise. Limited studies have assessed sounds from the perspective of psychophysiological comfort.

Subjective voting and physiological signals are recognized as valid indicators of sound evaluation. Psychologically, noise exposure primarily elicits annoyance and stress29, emotions that can be assessed through subjective measures like sound comfort votes (SCV) and sound pleasure votes (SPV)15. Physiologically, sound affects autonomic nervous system (ANS) and central nervous systems (CNS). Yang et al.30 found that as SPLs increased, the influence of noise on increasing LF/HF also intensified. Annerstedt et al.31 reported that exposure to natural sounds led to a reduction in LF/HF, facilitating effective stress recovery. Additionally, Yang et al.30 observed that higher noise levels were associated with lower SDNN. Li et al.32 found that natural sounds could enhance physiological comfort, leading to an increase in SDNN. These findings suggest that a decrease in LF/HF and an increase in SDNN are associated with enhanced ANS comfort activity. The brain makes up just 2% of the body’s weight but uses 20% of its oxygen, plays a crucial role in processing internal and external information. Electroencephalogram (EEG) reflects the periodic changes in cortical electrical activity on the scalp and quantitatively describes the brain’s energy consumption33. Different frequency bands may exhibit unique responses to different sound stimuli. δ are typically associated with drowsiness and deep sleep states34. Noise exposure has been found to increase γ activity, which is often linked to negative emotions and heightened arousal35. Asakura et al.36 reported that, compared to no sound, TN suppressed α and β oscillatory activity, whereas SWS enhanced θ, α, and β activity, indicating a more relaxed state. Similarly, Li et al.37 reported that exposure to natural sounds increased α and β power, contributing to stress recovery. Among different brainwave frequencies, α are considered an effective indicator of neural activity in the brain and are closely associated with comfort and relaxation38. Jafari et al.39 and Asakura et al.40 found that TN decreases α power, whereas SWS increase it, enhancing psychophysiological comfort—a finding also supported by Li et al.41. Different brain regions respond variably to sound stimuli, suggesting that these relationships require further exploration42. Beyond the commonly used dynamic features of EEG, such as the effective delay duration (τe) of α oscillatory activity, have been demonstrated to correlate with subjective preference and positive emotions, indicating more complex brain activity28. Additionally, the brain demonstrates both oscillatory and avalanche dynamics, with the latter akin to high-amplitude bursts indicating a shift towards a comfortable state due to slowed neuron activity43,44. This is associated with a smaller avalanche critical index (ACI), suggesting reduced nervous system stimulation by external stimuli45. The ACI has been effectively used in studies of indoor environments to reveal correlations between thermal comfort and brain activity, offering new perspectives for assessing sound comfort43. These findings provide an effective method to study the effect of sound on psychophysiological comfort. As the brain is an important organ for receiving and processing sound information, it is essential to understand the influence of TN and SWS of different SPLs on heart-brain activity more comprehensively, and master the changes of ECG and dynamics features of EEG. Although previous studies have explored the effects of TN and SWS, most have been limited to subjective evaluations or psychological aspects, lacking in-depth analysis of physiological signals such as EEG. This study integrates psychological assessments with ECG and EEG data, providing a more comprehensive evaluation approach to better understand the physiological mechanisms underlying sound perception.

In this context, the study objectives are to investigate the psychophysiological differences and relationships between exposure to TN and SWS at varying SPLs. Firstly, psychological responses are evaluated using SCV and SPV. Secondly, physiological comfort was assessed using ECG (LF/HF, SDNN), EEG frequency-domain features (power of different frequency bands), and nonlinear dynamic features (τe, avalanche parameters). The different effects of different sound are compared using one-way ANOVA, while the Spearman correlation coefficient is employed to explore the relationship between psychological and physiological comfort. This study provides an effective approach for evaluating indoor sound comfort and offers scientific evidence for optimizing building acoustic environments and intelligent soundscape control. These findings contribute to the improvement of personalized indoor environmental control systems and the enhancement of human well-being.

Materials and methods

Experimental environment and device

The experiment took place in the climate laboratory of the iSMART (3 m × 3 m × 2.6 m, see Fig. 1). It took place from January 3rd to March 4th, 2024, running daily from 10:00 am to 12:00 am. To minimize external influences and maintain participant comfort, the PMV was controlled to not exceed ± 0.5. Participants wore clothing with a thermal resistance of 1.0 clo and had a metabolic rate of 1.0 met. Room conditions were maintained at a temperature of 24 ± 0.5℃, RH at 50 ± 5%, and the air velocity from the air conditioning was set at 0.05 m/s, ensuring comfort levels were unaffected, as detailed in Table 2. The laboratory’s sound insulation is effective, and indoor illumination was controlled at 300 lx, 4000 K. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of iSMART.

In this study, ECG signals were recorded by the Healink-R211B (Healink, China, 1000 Hz). EEG signals were collected by the EPOC Flex Saline Sensor Kit (Emotiv Inc., USA, 128 Hz). The device’s 32 electrode positions were aligned according to the 10–20 system. Prior to data collection, the felt pads were immersed in normal saline to boost conductivity. Recording began after verifying that the impedance levels were under 10 kΩ, guaranteeing superior signal quality.

Participants

The recruitment information was posted on the official website of iSMART, with a brief introduction of the experimental purpose and process. Criteria for volunteers included good hearing and the absence of any mental health issues or sleep disorders. A total of 38 young college students (19 males and 19 females, 22.08 ± 2.76 years) were recruited (see in Table 3). They all come from the architecture major. Participants underwent a hearing screening test using a GSI 18 audiometer within a soundproof compartment, confirming normal hearing ranges between 0 and 25 dBA HL13. In the 24 h leading up to the experiment, Participants were advised to refrain from smoking, alcohol consumption, neurostimulant beverages, and neurogenic drugs, while also ensuring adequate sleep46. Additionally, participants were instructed to avoid strenuous activities for at least five hours before the experiment to maintain stable physiological indicators within normal ranges5.

Subjective evaluation

The subjective questionnaires used in this study are divided into basic information survey and sound perception evaluation. Before the experiment began, participants completed a survey that collected basic information such as age, gender, and health status. Following each sound exposure, participants were required to complete the sound perception evaluation, which included sound comfort votes (SCV) and sound pleasure votes (SPV) (see Fig. 2)47. SCV represents participants’ ratings of the overall comfort of the sound environment, with higher scores indicating a greater level of comfort. SPV reflects participants’ ratings of emotional pleasure within the sound environment, where higher scores signify a stronger sense of auditory-induced enjoyment. Both SCV and SPV are assessed using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from − 3 to 3, where − 3 represents extremely uncomfortable/unpleasant, 0 indicates normal, and 3 signifies extremely comfortable/pleasant. These measures enable the quantification of participants’ subjective perceptions of different sounds48. SCV and SPV provide a more comprehensive and human-centered evaluation of the sound environment compared to purely physical acoustic parameters22,47. Subjective comfort and pleasure not only influence psychological experiences but also impact physiological indicators48. Therefore, this study adopts SCV and SPV as subjective measurement methods.

Experimental procedure

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the effects of different sounds on psychophysiological comfort. TN, a prevalent form of indoor acoustic pollution, negatively affects concentration and cognitive performance. In contrast, SWS is a common natural sound49. According to Chinese classroom acoustics standards, 40 dBA and 45 dBA are considered optimal SPLs50. Research indicates that noise levels exceeding 50 dBA can distract college students, and it is recommended that office noise levels should not surpass 60 dBA51,52. Commonly, recommended SPLs range from 40 to 60 dBA, with increments of 5 dB generally accepted53,54. Consequently, this study established ten different sound conditions, featuring both TN and SWS at 40, 45, 50, 55, and 60 dBA, alongside a no sound control group. The sound spectrum can be seen in Fig. 3.

The laboratory’s background noise level ranged from 11 to 13 dBA. To ensure accurate SPLs, a head and torso simulator (Brüel & Kjær 4100) and Adobe Audition software were employed for calibration41. The headphones were positioned on the simulator’s ears, and SWS recordings were played in stereo through Adobe Audition. A SPL meter (SVAN 977 A SVANTEK) was placed near the simulator’s ears to measure the actual SPLs. Adjustments were made in Adobe Audition until the A-weighted equivalent continuous sound levels (LAeq,3-min) reached 40, 45, 50, 55, and 60 dBA, meeting the experimental requirements5. The study employed headphones (Sennheiser HD 280 Pro), which provide high external noise attenuation of up to 32 dB, effectively minimizing background noise42.

Figure 4 shows the experimental procedure. To prevent fatigue from the lengthy experimental sessions, half of the participants listened to TN at five different SPLs on the first day and SWSs on the second day. The other half listened to SWSs at five different SPLs on the first day and TN on the second day. Before beginning the experiment, participants were given 30 min to relax and were equipped with the ECG and EEG device. The experimental process was then briefly explained, lasting no more than 5 min. Participants were instructed to stay seated all the time. Subsequently, ECG and EEG were recorded for 5 min under no sound to establish a baseline. Next, participants listened to a specific sound for 5 min, during which EEG data continued to be collected. During this period, the participants remained with their eyes closed. After each sound exposure, participants filled out the subjective questionnaire. Finally, a 5-minute rest period was provided before proceeding to the next sound set. Each sound exposure was presented in a random order.

ECG signals processing

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a widely used parameter in ECG analysis to measure fluctuations in the intervals between consecutive heartbeats. Among HRV parameters, the ratio of low-frequency (LF, 0.04–0.15 Hz) to high-frequency (HF, 0.15–0.4 Hz) power (LF/HF) is an indicator of the ANS ability to regulate HR55,56. A decrease in LF/HF indicates greater parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity, which is generally linked to reduced stress and enhanced comfort35,57. Additionally, an increase in SDNN (the standard deviation of normal-to-normal heart intervals) suggests sympathetic nervous system (SNS) inhibition and PNS dominance, reflecting a more relaxed and healthier psychological state. Therefore, LF/HF and SDNN serve as physiological indicators to assess the influence of different sound environments on physiological comfort.

EEG signals processing

EEG preprocessing

To ensure the cleanliness of EEG data and minimize the impact of noise and artifacts on results, a standard preprocessing protocol is implemented prior to data analysis. The preprocessing involves the following four steps: (1) Channel localization and filtering, which involves aligning EEG data with channel information and applying bandpass filtering to retain only the frequencies within the range of 1–45 Hz. (2) Repeated referencing, using the average reference method. (3) Independent component analysis (ICA), aimed at removing artifacts and improving the signal-to-noise ratio. (4) Removal of bad segments, which entails deleting data of poor quality. If the data contamination range exceeds 50%, all data of that participant will not be included in subsequent analysis. EEG data were split into 2-s length epochs that overlapped 1 s, and 50% of the power spectral density (PSD) in the range of 1–45 Hz was extracted using the p-welch function. All of the above steps are done using EEGLAB in Matlab 2016b (Mathworks, USA).

Power

Different EEG frequency bands are associated with various states and cognitive abilities. δ (0.5–4 Hz) is linked to deep sleep, while θ (4–8 Hz) is associated with REM sleep and meditation. β (13–30 Hz) and γ (> 30 Hz) are related to wakefulness and cognitive processing36,58, whereas α (8–13 Hz) is commonly associated with a relaxed mental state. Power is a commonly used indicator to reflect the strength of oscillatory activity within each frequency band. Higher power values indicate more pronounced oscillatory activity in the respective frequency range. Due to the large magnitude of the calculated results, a logarithmic transformation is often performed (as shown in Eqs. 1–2).

Where, Pk is absolute power, i is the lower frequency and j is the upper frequency of the band. FFTn is the series extracted from time domain data by Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Pl is Pk after logarithmic transformation.

Effective delay duration (τe)

The autocorrelation function (ACF) is used to describe the correlation on the time series of EEG signals59,60,61. If α oscillatory activity contains a significant repeating pattern, ACF will show a significant peak at the corresponding delay time point28, and the calculation method is shown in Eq. (3).

Where, N is the length of the signal, x (t) is the value of the signal at time point t, x ̅ is the mean of the signal, and τ is the delay time. τe is the time required for the signal to decay from its peak to its initial value. The greater the τe, the longer the correlation of the signal in time, and the more regular α oscillation activity, which is linked to increased comfort [24].

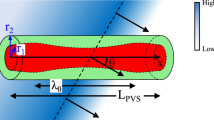

Brain avalanche parameters

Some studies strengthen that the brain can be regarded as a self-organizing critical system, functioning optimally when in a critical state. Research indicates that the brain experiences massive bursts of neuronal activity, similar to avalanche activity in dynamics, propagating in a form that satisfies a power-law distribution. Using a power-law index of avalanche duration (AD) and size (AS), the avalanche critical index (ACI) that describes the scale of avalanche activity in the brain can be obtained. A lower ACI indicates that the brain activity is closer to this critical state, thereby being more comfortable and healthy62. The specific analysis method is as follows: (1) Detection of avalanche activity: This step involves determining whether avalanche activity has occurred, specifically if activity exceeding a predefined threshold has taken place within a set time window. The time window used here is 31.2ms, which is four times the time resolution. The threshold is defined as the mean ± SD of the entire signal. Once brain activity surpasses this threshold, it is recorded as an event. (2) Measurement of avalanche events: AD refers to the number of the time window during which continuous avalanche activity occurs. AS is determined by the total number of events within these time windows. (3) Calculation of ACI: ACI is calculated using the fit value and the calculated value of the avalanche event63. In this study, maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) is employed to calculate power law indices of the size (k1), duration (k2), and average size (k3) of avalanche activities [as shown in Eqs. (4)–(8)]64,48.

Data analysis

Data analysis mainly uses three methods: (1) The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test was employed to assess whether the data followed a normal distribution. (2) One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized to examine the effects of two or more factors on the dependent variable. If p < 0.05, there is a significant difference. After the Bonferroni test was adopted, Eta2 represented the impact effect size, and the larger the value, the bigger the impact effect. 0.01, 0.06, and 0.14 represented small, medium, and large effects, respectively65. (3) Spearman test was used to reflect the correlation among SCV, SPV, ECG, and EEG under different sound conditions. The higher the correlation coefficient (r), the stronger the correlation: 0.40 (weak), 0.70 (medium), and 0.90 (strong), respectively66.

Results

The results indicate that while SCV, SPV, LF/HF, SDNN, power of α, δ, θ, β and γ, τe, k1, k2, and ACI are not perfectly normal, they can generally be accepted as normally distributed for analytical purposes, given that the absolute value of kurtosis is less than 10 and the absolute value of skewness is less than 3. The ANOVA results are presented in Table 4. Different sounds have a significant impact on SCV, SPV, and ACI, with Eta2 of 0.591, 0.496, and 0.359, respectively. Detailed analyses of these results are discussed in the following sections.

Analysis of the psychological responses

Figure 5 shows the results of sound comfort and pleasure under different sound conditions. Regarding sound comfort, SWS is significantly better than TN, with SCV increasing by 0.26–2.68. Compared to no sound, SWS consistently demonstrated a positive effect, enhancing SCV by 0.16–0.95, whereas TN had a detrimental effect. As SPLs increased, SCV for SWS initially rose and then declined, reaching its peak (1.32) at 50dBA. In contrast, SCV for TN decreased with increasing SPLs, hitting its lowest point (-1.89) at 60dBA. Similarly, the results of SPV mirrored those of SCV. The most substantial enhancement in pleasure occurred at 50dBA SWS. Compared to 60dBA TN, which had the most adverse effect, SPV significantly increased by 2.21 (p < 0.001). Interestingly, at 40dBA, the effects of SWS, TN, and no sound on sound comfort and pleasure were similar, with SCV and SPV ranging from 0.26 to 0.53 and 0.05–0.16, respectively. As SPLs increased, the differences in SCV and SPV between SWS and TN first increased and then decreased. The SCV and SPV of SWS at 55dBA were 2.68 and 2.47 higher than those of TN (p < 0.001). Overall, at 50dBA SWS was the most favorable in terms of psychological responses, corroborating the findings of Hsieh et al.67.

Analysis of the physiological responses

LF/HF

In Fig. 6, at the given SPLs, LF/HF for SWS remained consistently lower than that for TN (by 0.03–0.55), suggesting enhanced PNS activity, which is linked to stress reduction. As SPLs increased, LF/HF for TN gradually increased, whereas LF/HF for SWS initially decreased and then increased, reaching its lowest value of 1.24 at 50 dBA. Compared to 60 dBA TN, LF/HF at 50 dBA SWS was significantly reduced by 0.40 (p < 0.05). Interestingly, compared to the no-sound condition, 40–50 dBA SWS reduced LF/HF by 0.07–0.41, whereas 55 dBA and 60 dBA SWS increased LF/HF by 0.01 and 0.05, respectively. In contrast, TN at 45–60 dBA increased LF/HF by 0.03–0.29 relative to no sound, while 40 dBA TN reduced LF/HF by 0.05, slightly improving comfort. These findings suggest that when the SPL exceeds 55 dBA, both TN and SWS suppress PNS activity, interfering with comfort.

SDNN

In Fig. 7, the SDNN for SWS was consistently higher than that for TN, with the largest difference of 19.42 ms observed at 50 dBA. As the SPL increased, SDNN for SWS initially increased and then reduced, achieving its peak at 50 dBA (63.69 ms), whereas SDNN for TN gradually decreased. Compared to the no-sound condition, SWS increased SDNN by 4.27–18.56 ms, while TN at 50–60 dBA decreased SDNN by 0.85–6.50 ms. TN at 40 dBA and 45 dBA showed SDNN values similar to no sound (45.13–45.22 ms). Overall, 50 dBA SWS significantly activated PNS, enhancing physiological comfort, whereas TN above 50 dBA had a pronounced negative effect on PNS, which could be detrimental to physiological health.

Power

To comprehensively understand the unique responses of different brain frequency bands to various sounds, this study compared the differences in δ, θ, α, β, and γ power under different sound conditions, with a particular focus on α activity analysis. As shown in Fig. 8(a), compared to the no sound, TN enhanced δ activity, with δ power increasing as SPL increased. In contrast, SWS suppressed δ activity, resulting in δ power lower than that in the no sound condition, with values stabilizing above 50 dBA (1.47–1.52 µv2). As shown in Fig. 8(b), SWS enhanced θ activity, with θ power exhibiting a U-shaped pattern as SPL increased, reaching its peak at 50 dBA, which was 0.23 µv2 higher than in the no sound condition. In contrast, as the SPL of TN increased, θ power decreased, showing a reduction of 0.10–0.16 µV2 compared to no sound. The effects of TN and SWS on β activity were similar to those on θ (see Fig. 8(c)). Compared to the no-sound condition, β power reduced by 0.12–0.22 µv2 under TN, while it increased by 0.12–0.24 µv2 under SWS. The changes in γ power under TN and SWS followed a pattern similar to δ (see Fig. 8(d)). With increasing SPL, γ power under TN increased, peaking at 60 dBA (1.76 µv2), which was 1.26 times that of the no-sound condition. Conversely, γ power under SWS was 0.10–0.21 µv2 lower than no sound, reaching its lowest value at 50 dBA (1.20 µv2). Overall, TN enhanced δ and γ activity, with stronger activation effects at higher SPLs, whereas SWS promoted θ and β activation, particularly at 50 dBA.

Figure 9 displays the plot of average α oscillation activity of all participants under different sound conditions. The darker the color, the more intense α oscillation activity68. SWS elicited greater α oscillatory activity compared to TN, particularly in the parietal and occipital lobes. As SPLs of TN increased, the color on the plot gradually faded. Specifically, α oscillation activity in the frontal lobe at 60 dBA TN was significantly reduced compared to that at 40 dBA. In contrast, with SWS, α oscillation activity first increased and then decreased with rising SPLs, reaching its peak activity at 50dBA, which is related to the comfortable state.

Figure 10 shows the results of α power under different sound conditions. The α power of SWS was consistently higher than that of TN, ranging from 0.13 to 0.52 µv2, with the difference being statistically significant (p < 0.001). At 40–50 dBA SWS, α power increased with rising SPLs. However, at 55 dBA and 60 dBA, α power initially decreased and then increased. In contrast, α power of TN decreased as SPLs increased. When compared with no sound, α power for TN at 40 dBA and 45 dBA increased slightly by 0.15 to 0.16 µv2, but for levels exceeding 50 dBA, α power decreased by 0.01 to 0.04 µv2. It is evident that α power at 50dBA SWS is the highest, indicating the greatest level of comfort. Conversely, exposure to TN above 50 dBA tends to have detrimental effects on brain comfort. These observations support the findings by Li et al.37, who noted that TN can increase brain stress levels and suppress α oscillatory activity.

The influence of different SPLs of TN and SWS on α power across various channels was further analyzed, with significant differences between groups shown in Fig. 11. Notable differences were observed in channels F3, FC1, C3, Cz, and O2 (p < 0.01, as detailed in Table 5), and the differences in α power in response to TN and SWS were similar to those observed in the whole brain. On F3, Cz, and O2, with the increase in SPLs, the α power of SWS exhibited an inverted U-shaped change, and was consistently 0.10–0.62 µv2 higher than that of TN at the same SPL. On FC1 and C3, as SPLs increased, the α power of TN decreased. The α power of SWS at 55–60 dBA was 0.10–0.35 µv2 higher than that of TN. It can be seen that the sensitive areas to sound stimulation are primarily in the left frontal-parietal lobe and the right occipital lobe, and the positive effect of high SPL SWS on α oscillatory activity is significantly better than that of TN. Indrani et al.69 and Wang et al.70 also reached similar conclusions that different brain lobes respond differently to different sound stimuli.

Effective delay duration

Figure 12 displays the results of τe under different SPLs of TN and SWS. The τe of SWS is consistently higher than that of TN, indicating more regular α oscillatory activity. Compared to no sound, the τe of SWS increases by 0.02–3.44 ms, whereas the τe of TN decreases by 0.49–8.73 ms. As SPLs increase, the τe of SWS initially rises and then decreases, with the peak increase of 0.76–3.42 ms observed at 50 dBA. Conversely, as SPLs of TN increase, the τe fluctuation decreases, reaching its lowest at 60 dBA (272.61 ms). Although no statistical difference was observed (p = 0.998), it is evident that SWS enhances the autocorrelation of α oscillatory activity in the brain, contributing to improved brain comfort.

Brain avalanche

Figure 13 shows the variation in k1 under different sound conditions. Compared to no sound (k1 = 1.87), k1 is larger under high SPLs SWS, indicating a more stable number and deviation degree of active neurons, which is more conducive to the recovery of brain stress levels to their baseline state45. At 40 dBA and 45 dBA, the probability of large avalanche activity is similar between TN and SWS, with k1 ranging from 1.86 to 1.88. At higher SPLs of 50–60 dBA, the probability of large-scale avalanche activity is significantly lower in SWS than in TN, with k1 increasing by 0.14–0.16. The lowest probability of large-scale avalanche activity occurs at 50 dBA, where k1 reaches 1.92. This suggests that SWS at higher SPLs is more conducive to maintaining a balance between the organized and chaotic phases of brain activity compared to TN.

Figure 14 shows the variation in k2 under different sound conditions. Compared to no sound (k2 = 1.48), k2 is larger under exposure to SWS, and the duration difference between the first and last neuron activation is shorter, which is closer to the theoretical value of 2.045. Similar to k1, at 40 dBA and 45 dBA, TN and SWS show similar probabilities of prolonged avalanche activity, with k2 ranging from 1.49 to 1.51. However, at higher SPLs of 50–60 dBA, the probability of long-term avalanche activity in SWS is significantly lower than that of TN, with k2 increasing by 0.13–0.18. The highest probability of prolonged avalanche activity occurs at 60 dBA TN, where k2 is 1.39. This finding indicates that traffic sound can induce long-term, large-scale cascade reactions in the brain, potentially pushing the brain into a supercritical state and leading to brain fatigue.

Figure 15 illustrates the power law indices of AS (k1) and AD (k2) across all participants under different SPLs of TN and SWS. The data points for k1 and k2 form an approximately linear distribution on the coordinate plane. Taking the average values under the no-sound condition (k1 = 1.87, k2 = 1.48) as the central reference, the plane is divided into four quadrants. In the lower-left quadrant, where both k1 and k2 are lower than under no sound, brain activity exhibits large-scale, long-duration bursts, indicating a shift in neural dynamics. This indicates that the nervous system consumes more power and deviates from a comfortable state43, mainly observed in participants exposed to TN (64.65%). Specifically, participants exposed to 45–60 dBA of TN comprised 63.15–84.21% of this group (as detailed in Fig. 16). In contrast, the upper-right quadrant represents a low-power consumption region, where energy expenditure is lower than in the no-sound condition. This quadrant is primarily occupied by participants exposed to SWS (67.57%), with those experiencing 50–60 dBA SWS accounting for 52.63–63.16% of the group. This suggests that SWS exposure, particularly at higher SPLs, enhances brain energy efficiency, supporting cognitive processing and comfort in integrating external information.

In order to more accurately reflect the brain activity’s distance from the critical state under different sound, avalanche critical index (ACI) was compared, as depicted in Fig. 17. A lower ACI signifies a closer approximation to the critical state, indicative of more comfortable and healthy brain activity43. The SWS was found to contribute to increased comfort, showing ACI significantly lower than those of no sound and TN (p < 0.001). Specifically, compared to the no-sound condition, exposure to high SPL of SWS resulted in a decrease in ACI by 0.01 to 0.04, corresponding to an increase in brain comfort by 4.78 to 17.29%. Notably, at 50 dBA, ACI reached its lowest value (0.20), where the improvement in comfort was most pronounced. On the other hand, ACI for TN gradually increased with the rise in SPLs. At 40 dBA, TN had the least disturbance on the brain, with ACI similar to that of no sound (0.239 and 0.243, respectively), and the highest ACI was observed at 60dBA (0.32). Overall, SWS notably helped improve brain health, especially at 50 dBA, whereas exposure to high SPLs of traffic sound had a detrimental effect.

Correlation analysis

Figure 18 shows the correlation analysis between subjective and objective indicators, demonstrating a significant correlation between psychological comfort and physiological comfort. SCV and SPV showed a significant negative correlation with LF/HF, δ and γ power, and ACI, while they were significantly positively correlated with SDNN, power of α, θ, and β, τe, k1, and k2 (p < 0.01). Additionally, there was a significant correlation between ECG and EEG. As LF/HF decreased, α, θ, and β power significantly increased (p < 0.01). Similarly, as SDNN increased, power of α, θ, and β showed a significant increase (p < 0.001), whereas δ and γ power significantly decreased (p < 0.05). Overall, this analysis confirms that there is a substantial link between psychophysiological comfort and the acoustic environment, aligning with the findings of Lu et al.43.

Discussion

The effects of TN on Psychophysiological comfort

Exposure to high SPL TN is detrimental to psychophysiological comfort34. Studies have consistently shown that noise exposure exacerbates subjective annoyance71, with annoyance levels escalating as SPL increases72. Our findings align with these observations, indicating that compared to no sound, SCV and SPV decrease by 0.11–2.26 and 0.06–1.85 respectively under TN exposure. Physiologically, the study found that compared to no sound, exposure to TN above 50 dBA led to an increase in LF/HF by 0.09–0.60 and a decrease in SDNN by 0.85–6.50 ms. This may be attributed to the increased auditory load induced by TN, which stimulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to the release of stress hormones (e.g., cortisol) and triggering cardiovascular system responses. Consequently, the SNS becomes highly activated, while the PNS is suppressed73, indicating a heightened state of psychological tension. As the SPL increases, these negative effects intensify. Li et al. also found that as SPL increased (55–85 dB), LF/HF increased by 0.34–0.53, while SDNN decreased by 1.71–8.60 ms30. Furthermore, the study found that TN reduced θ, α, and β power while increasing δ power, which is consistent with the findings of Li et al.74. Additionally, TN exposure above 50 dBA has been found to suppress α oscillatory activity, consequently elevating stress levels, which corroborates the findings of Li et al.32. Further analysis revealed that TNs exceeding 50 dBA lead to a decrease in k1 and k2 by 0.11–0.14 and 0.12–0.23, respectively. This increase in the probability of long-term and large-scale avalanche activity contributes to more disordered brain activity, which adversely affects comfort45,75. Additionally, ACI increased by 0.05–0.08 compared to no sound, indicating that the brain was in a supercritical state characterized by intense activity and higher power consumption. This reduces the resources available for information integration and cognition, thereby lowering comfort levels. In this study, TNs at 40dBA and 45 dBA exhibited fewer negative effects and also stimulated α oscillatory activity associated with relaxed states. Some studies found that appropriate short-term exposure to TN can enhance visual cognitive work performance15, potentially boosting attention and resistance to noise interference75. At a medium arousal level, work efficiency is at its peak76. However, when noise reaches or exceeds 50dBA, reaction times slow as SPL increases, and the detrimental impacts on psychophysiological health escalate rapidly at higher noise levels77. In summary, exposure to TN has a negative impact on psychophysiological comfort, and this effect increases with higher sound pressure levels.

The effects of SWS on Psychophysiological comfort

The SWS has a beneficial influence on psychophysiological comfort. Recognized as a typical natural sound, SWS not only enhances approach motivation and positive emotions but also increases comfort69. Under exposure to SWS, the PNS was significantly activated. Compared to the no-sound condition, LF/HF decreased by 0.07–0.41, while SDNN increased by 8.85–18.56 ms under 40–50 dBA SWS exposure, suggesting enhanced physiological comfort. Moreover, this positive effect strengthened as SPLs increased, which is consistent with the findings of Annerstedt et al.31. SWS is known to reduce cortisol secretion and regulate limbic system activity, particularly in the amygdala78, thereby reducing SNS excitability and enhancing parasympathetic function79,80. This study also found that SWS enhanced θ, α, and β activity while suppressing δ activity, which aligns with previous research36,74. This study found that SWS, ranging from 40 to 60 dBA, improves brain comfort and boosts α power by 0.25–0.51 µv2. Li et al. also observed that α oscillatory activity increases under the influence of natural sounds37. Additionally, τe was found to significantly increase by 0.02–3.44 ms. Frescura et al. noted that this increase in τe is associated with enhanced perceptions of pleasure and satisfaction28. However, this study identified that the positive effects of SWS exhibit an inverse-U-shaped response to SPLs, with the 50 dBA showing more significant benefits compared to 40, 45, 55, and 60 dBA. The ACI for 50 dBA SWS was the lowest, being 0.12 less than that for 60dBA TN, and brain comfort improved by 36.48%. Meng et al. also found that the positive sound at 50 dBA significantly enhanced the sense of pleasure compared to 40 dBA and 60 dBA81. It is important to note that the duration of exposure may influence these improvements. Some research suggests that a 3-minute exposure can yield effects1, while other studies advocate for a 20-minute exposure to aid in comfort restoration82. This study used a fixed exposure duration of 5 min, indicating that further exploration into optimal recovery times is necessary. In conclusion, moderate SPLs of SWS are particularly effective in enhancing psychological and physiological comfort. Utilizing 50 dBA of SWS in indoor sound environment design could improve the comfort of occupants. However, the specific exposure duration required for recovery need further investigation.

The correlation of psychophysiological comfort

Psychological and physiological comfort are significantly correlated83,84. SCV and SPV showed a significant negative correlation with LF/HF, δ and γ power, and ACI, while they were significantly positively correlated with SDNN, power of α, θ, and β, τe, k1, and k2 (p < 0.01). These findings support the interconnectedness of psychological and physiological comfort as suggested by Li et al.32 and Mir et al.29. The SNS and PNS are responsible for stress responses and relaxation, respectively85. When individuals subjectively feel comfortable, PNS activity becomes more dominant86, whereas negative emotions are associated with reduced PNS activity85. When discomfort is perceived subjectively, the brain responds by releasing neurotransmitters (e.g. dopamine and serotonin), which are linked to pleasure and satisfaction. This process promotes PNS activation, thereby enhancing both psychological and physiological comfort. Sound stimulation affects the limbic structures of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and nucleus accumbens, modulating individual emotions through changes in neurotransmitter release87. An increase in negative emotions activates the hypothalamus, which releases neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin, associated with happiness and satisfaction, to combat stress88,89. δ, θ, α, β, and γ can serve as important indicators for reflecting sound-induced emotions. Mir et al.29 also confirmed that these five frequency bands are effective in identifying emotional responses to sound and developed a corresponding model. This finding provides new insights for future personalized sound environment design. In various brain frequency bands, α oscillation activity serves as an effective comfort level indicator38. Different brain regions have distinct roles in processing these emotional responses. For instance, the frontal lobe, highly sensitive to emotional stimuli, shows increased neural activity in response to unpleasant sounds90. Significant differences in frontal lobe activity are observed when processing natural versus artificial sounds42, with frontal α oscillatory activity being closely linked to emotional changes90,91. Sound stimulation typically induces a left-sided brain activity pattern29, with increased left frontal α oscillatory activity correlating with positive emotions90. Furthermore, sound affects directed attention allocation in the brain, primarily involving the frontal and parietal lobes69. Stobbe et al.69 noted significant differences in parietal brain activity due to sound stimulation, and Codispoti et al.38 found that subjective comfort was linked to parietal α oscillatory activity. An increase in parietal α oscillatory activity indicates a lower mental load70. Additionally, sound processing involves regions beyond the auditory cortex, such as the visual regulatory cortex42,92, with Ma et al. highlighting the close association of the O2 with comfort93. Similar to these findings, this study identified that the left frontal-parietal lobe (F3, FC1, C3, Cz) and the right occipital lobe (O2) are particularly sensitive to TN and SWS at varying SPLs (p < 0.01). Future research could focus on these areas to streamline the EEG setup by reducing unnecessary electrodes, thereby simplifying signal acquisition and processing. Different frequency bands respond differently to various sounds. Future research can further explore the key neural pathways associated with these frequency bands to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms by which different sounds influence brain activity.

Indoor sound can significantly influence well-being, exerting either negative or positive effects on individuals. The SWS, is known to enhance comfort and elevate mood, particularly for those engaged in monotonous and repetitive tasks. A moderate SPL is generally more satisfying as excessively high SPLs can substantially increase subjective annoyance, diminish work motivation, and interfere with cognitive functions such as concentration, potentially leading to auditory fatigue94. Conversely, low SPLs sounds or quiet environments might not elicit a strong positive activation response. Research indicates that 50dBA SWS provides optimal improvement in terms of enhancing psychophysiological comfort, whereas TN exceeding 50 dBA tends to adversely affect comfort, suggesting that the brain may be particularly sensitive to 50 dBA94. Future studies could further explore effects of SPL on neural mechanisms. The study also uncovered individual differences in effects of different sound conditions on brain dynamics activity. Compared to no sound, 64.65% of participants exhibited an increased likelihood of higher brain power consumption under TN exposure, whereas 67.57% showed reduced power consumption under exposure to SWS. These variations may be attributed to factors such as individual sensitivity to sound and gender28,95, which warrant further exploration. In conclusion, TN and SWS at varying SPLs can significantly influence psychophysiological comfort, with effects deeply modulated by individual factors. Future research in neuroarchitecture and environmental psychology could provide deeper insights into these interactions, helping to optimize indoor sound environments for health and well-being.

Application and limitations

Traditional evaluations of building acoustic environments primarily rely on physical acoustic parameters and subjective assessments, which may not fully capture the psychophysiological effects of sound. This study integrates subjective evaluations with physiological signals, providing a multi-level analytical framework and innovatively incorporating the nonlinear dynamical characteristics of brain activity. ECG and EEG signals can directly reflect the real-time responses of the ANS and brain activity to the acoustic environment, avoiding potential biases associated with purely subjective surveys30,37. Through statistical analysis, this study quantifies the influence of different sound conditions on emotions and heart-brain activity. This comprehensive approach not only assesses the impact of sound on psychological and physiological health but also reveals the regulatory role of the ANS and the response patterns of different brain regions, providing scientific evidence for the design of healthy acoustic environments. The findings indicate that SWS has strong restorative effects, particularly at 50 dBA. This suggests that incorporating 50 dBA SWS in environments such as offices, schools, hospitals, and residences can optimize the soundscape and enhance comfort. In high-noise areas (e.g., airports and commercial districts), integrating water features can help mask noise and improve environmental quality. Additionally, appropriate SWS exposure can be beneficial for mental health therapy and stress management, improving the effectiveness of health interventions. By integrating physiological monitoring technologies, it is possible to provide real-time feedback on acoustic environment quality, guiding noise reduction and soundscape optimization strategies. Portable wearable physiological devices can be utilized to continuously monitor ECG and EEG variations, dynamically adjusting indoor sound environments based on users’ physiological responses, enabling personalized soundscape optimization. Some researchers have also developed sound-emotion recognition models based on EEG and other physiological signals29. This study further identifies that the left frontoparietal region (F3, FC1, C3, Cz) and right occipital region (O2) exhibit the most significant responses to sound comfort, suggesting that these regions could serve as key EEG feature extraction channels to simplify sound-emotion recognition models. Moreover, the study confirms that the nonlinear dynamical characteristics of brain activity are closely related to sound comfort, highlighting their potential role in enhancing the performance of sound-emotion recognition models. In summary, this study establishes a novel feedback mechanism for evaluating building acoustic environments, integrating subjective assessments with ECG and EEG signals. This approach provides scientific support for optimizing acoustic environments in offices, residences, and other buildings and, when combined with smart building technologies, promotes the development of healthy acoustic environments. The findings also contribute to the scientific formulation of building acoustic environment standards, offering a more data-driven and evidence-based approach to soundscape design. However, there are some limitations to the study. Only TN and SWS were selected as sound stimuli, considering that different sound sources might have different effects on perception and physiological activities. Therefore, it is essential to explore more sound types in the future. Additionally, the experiment was conducted in the common SPLs range of 40–60 dBA, considering that there may be extreme sound environments indoors, the research scope of SPL should be broadened. Thirdly, this study chose participants sitting with a low metabolic rate. Studies have shown that different activity states will also affect the experimental results. It is recommended to further investigate how various sounds affect comfort levels during different activities. Fourthly, to prevent fatigue from long-term experiments, the study concentrated on the effects of 5-minute sound exposures on comfort. However, in real-life scenarios, the impact of sound can be long-term. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the influence of prolonged sound exposure on comfort. Lastly, previous studies have shown that when humans are tested in laboratory settings, they are very similar worldwide. However, significant differences exist when they are in their own apartments. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen field research in the future.

Conclusions

This study investigated the differences in comfort levels of young college students under various sound pressure levels (SPLs) of traffic noise (TN) and spring water sound (SWS) through psychophysiological responses. Key findings are as follows:

-

Compared to no sound, SWS significantly enhanced psychological comfort, with sound comfort votes (SCV) and sound pleasure votes (SPV) increasing by 0.10–0.95 and 0.05–1.10, respectively. As sound pressure levels (SPLs) of TN increased, both SCV and SPV exhibited continuous declines, ranging from 0.11 to 2.26 and 0.06–1.85, respectively.

-

SWS more effectively promotes parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity than TN. As SPL increased, LF/HF for SWS decreased initially, reaching its lowest (1.24) at 50 dBA, then increased, while TN LF/HF continuously rose. Above 55 dBA, both sounds increased LF/HF (0.01–0.29), negatively impacting comfort. SDNN for SWS remained higher than for TN (by 8.76–19.42 ms). It peaked at 50 dBA (63.69 ms), where the largest gap (19.42 ms) occurred, indicating significant PNS activation and enhanced physiological comfort.

-

TN activated δ and γ while suppressing θ and β. The α power, associated with relaxation, initially increased and then decreased with rising SPLs of SWS. The peak α power was recorded at 50 dBA (2.10 µv2), indicating the highest comfort level. The left frontal-parietal lobe (F3, FC1, C3, Cz) and the right occipital lobe (O2) were most responsive to both TN and SWS at varying SPLs (p < 0.01).

-

The effective delay duration (τe), for SWS was consistently greater than for no sound or TN (0.02–8.76 ms), suggesting enhanced regularity in brain activity. Notably, the optimal 50dBA SWS increased τe by 12.18 ms compared to the worst 60 dBA TN.

-

Between 50 and 60 dBA, the SWS exhibited markedly less large-scale and long-duration avalanche activity compared to TN, with increases in k1 and k2 of 0.14–0.16 and 0.13–0.18 respectively, indicating a closer approach to a comfortable state. In comparison with no sound, 52.63–63.16% of participants exposed to 50–60 dBA SWS showed lower brain power consumption, enhancing efficiency.

-

The avalanche critical index (ACI) for SWS decreased by 0.02–0.10 compared to TN, reflecting a higher comfort level. Notably, the 50 dBA SWS demonstrated the most significant improvement, with the brain comfort level being 1.74 times higher than that of TN.

-

The effects of TN and SWS at various SPLs on SCV, SPV, and ACI are statistically significant (p < 0.001), with effect sizes (Eta2) ranging from 0.359 to 0.591. SCV and SPV show a significant positive correlations with power of α, θ and β, τe, k1, and k2 (p < 0.05). Conversely, SCV and SPV both show strong negative correlations with δ and γ power, and ACI (p < 0.001).

This study explores the effects of TN and SWS at different SPLs on psychophysiological comfort and proposes a sound environment evaluation method that integrates subjective assessments with ECG and EEG signals. The findings reveal the sensitivity of different brain regions to auditory stimuli and confirm that 50 dBA SWS provides the optimal comfort effect. Additionally, this study expands research on effects of natural sounds on brain dynamic activity, laying a foundation for future soundscape optimization and neuroarchitecture studies. These findings can be applied to soundscape design in offices, hospitals, and other environments and can be integrated with building intelligent control systems to achieve personalized sound environment optimization. Future research should further explore different sound types, the long-term effects of exposure, and intelligent sound environment control systems to promote the development of healthier indoor acoustic environments.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Wen, X. et al. Effect of thermal-acoustic composite environments on comfort perceptions considering different office activities. Energy Build. 305, 1–10 (2024).

Rajashekar, U., Bovik, A. C. & Cormack, L. K. Visual search in noise: revealing the influence of structural cues by gaze-contingent classification image analysis. J. Vis. 6, 7 (2006).

Shin, S. et al. Association between road traffic noise and incidence of diabetes mellitus and hypertension in Toronto, Canada: a population-based cohort study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e013021 (2020).

Golmohammadi, R. et al. Attention and short-term memory during occupational noise exposure considering task difficulty. Appl. Acoust. 158, 107065 (2020).

Long, X. et al. The impact of outdoor soundscapes at nursing homes on physiological indicators in older adults. Appl. Acoust. 221, 1–10 (2024).

Kaarlela-Tuomaala, A. et al. Effects of acoustic environment on work in private office rooms and open-plan offices – longitudinal study during relocation. Ergonomics 52, 1423–1444 (2009).

Cohen, S. & Weinstein, N. D. Nonauditory effects of noise on behavior and health. J. Soc. Issues. 37, 36–70 (1981).

Schlittmeier, S. J. et al. The impact of background speech varying in intelligibility: effects on cognitive performance and perceived disturbance. Ergonomics 51, 719–736 (2008).

Kallinen, K. Reading news from a pocket computer in a distracting environment: effects of the tempo of background music. Comput. Hum. Behav. 18, 537–551 (2002).

Alvarsson, J. J., Wiens, S. & Nilsson, M. E. Stress recovery during exposure to nature sound and environmental noise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 7, 1036–1046 (2010).

Guan, H. et al. People’s subjective and physiological responses to the combined thermal-acoustic environments. Build. Environ. 172 (2020).

Yang, W. & Moon, H. J. Combined effects of acoustic, thermal, and illumination conditions on the comfort of discrete senses and overall indoor environment. Build. Environ. 148, 623–633 (2019).

Yang, W. & Moon, H. J. Combined effects of sound and illuminance on indoor environmental perception. Appl. Acoust. 141, 136–143 (2018).

Pierrette, M. et al. Noise effect on comfort in open-space offices: development of an assessment questionnaire. Ergonomics 58, 96–106 (2015).

Meng, Q., An, Y. & Yang, D. Effects of acoustic environment on design work performance based on multitask visual cognitive performance in office space. Build. Environ. 205 (2021).

Hong, J. Y. et al. Effects of adding natural sounds to urban noises on the perceived loudness of noise and soundscape quality. Sci. Total Environ. 711, 134571 (2020).

Yang, W. & Moon, H. J. Effects of recorded water sounds on intrusive traffic noise perception under three indoor temperatures. Appl. Acoust. 145, 234–244 (2019).

Cai, J. et al. Effect of water sound masking on perception of the industrial noise. Appl. Acoust. 150, 307–312 (2019).

Jeon, J. Y. et al. Perceptual assessment of quality of urban soundscapes with combined noise sources and water sounds. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 127, 1357–1366 (2010).

Stansfeld, S. A. et al. Aircraft and road traffic noise and children’s cognition and health: a cross-national study. Lancet 365, 1942–1949 (2005).

Clark, C. et al. Does traffic-related air pollution explain associations of aircraft and road traffic noise exposure on children’s health and cognition? A secondary analysis of the united Kingdom sample from the RANCH project. Am. J. Epidemiol. 176, 327–337 (2012).

Chan, Y. N. et al. Influence of classroom soundscape on learning attitude. Int. J. Instr. 14, 341–358 (2021).

Lee, P. J. & Jeon, J. Y. Relating traffic, construction, and ventilation noise to cognitive performances and subjective perceptions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 134, 2765–2772 (2013).

Van Kempen, E. et al. Neurobehavioral effects of exposure to traffic-related air pollution and transportation noise in primary schoolchildren. Environ. Res. 115, 18–25 (2012).

Van Kempen, E. et al. The role of annoyance in the relation between transportation noise and children’s health and cognition. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 128, 2817–2828 (2010).

Van Kempen, E. E. et al. Children’s annoyance reactions to aircraft and road traffic noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 895–904 (2009).

Clark, C. et al. Exposure-effect relations between aircraft and road traffic noise exposure at school and reading comprehension: the RANCH project. Am. J. Epidemiol. 163, 27–37 (2006).

Frescura, A. et al. EEG alpha wave responses to sounds from neighbours in high-rise wood residential buildings. Build. Environ. 242 (2023).

Mir, M. et al. Investigating the effects of different levels and types of construction noise on emotions using EEG data. Build. Environ. 225 (2022).

Yang, B. et al. Effects of thermal and acoustic environments on workers’ psychological and physiological stress in deep underground spaces. Build. Environ. 212 (2022).

Annerstedt, M. et al. Inducing physiological stress recovery with sounds of nature in a virtual reality forest—results from a pilot study. Physiol. Behav. 118, 240–250 (2013).

Li, Z., Ba, M. & Kang, J. Physiological indicators and subjective restorativeness with audio-visual interactions in urban soundscapes. Sustain. Cities Soc. 75 (2021).

Lee, M., Shin, G. H. & Lee, S. W. Frontal EEG asymmetry of emotion for the same auditory stimulus. IEEE Access. 8, 107200–107213 (2020).

Zhang, N. et al. A review of EEG signals in the acoustic environment: brain rhythm, emotion, performance, and restorative intervention. Appl. Acoust. 230 (2025).

Järvelin-Pasanen, S., Sinikallio, S. & Tarvainen, M. P. Heart rate variability and occupational stress—systematic review. Ind. Health. 56, 500–511 (2018).

Asakura, T. Effects of face-to-face confrontation with another individual on the physiological response to sounds. Appl. Acoust. 213 (2023).

Li, Z. & Kang, J. Sensitivity analysis of changes in human physiological indicators observed in soundscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 190 (2019).

Codispoti, M., De Cesarei, A. & Ferrari, V. Alpha-band oscillations and emotion: A review of studies on picture perception. Psychophysiology 60, e14438 (2023).

Jafari, M. J. et al. The effect of noise exposure on cognitive performance and brain activity patterns. Open. Access. Maced J. Med. Sci. 7, 2924 (2019).

Asakura, T. Relationship between subjective and biological responses to comfortable and uncomfortable sounds. Appl. Sci. 12, 3417 (2022).

Li, Z., Ba, M. & Kang, J. Physiological indicators and subjective restorativeness with audio-visual interactions in urban soundscapes. Sustain. Cities Soc. 75, 103360 (2021).

Stobbe, E., Forlim, C. G. & Kühn, S. Impact of exposure to natural versus urban soundscapes on brain functional connectivity, BOLD entropy and behavior. Environ. Res. 244 (2024).

Lu, M. et al. Critical dynamic characteristics of brain activity in thermal comfort state. Build. Environ. 243 (2023).

Arviv, O., Goldstein, A. & Shriki, O. Near-critical dynamics in stimulus-evoked activity of the human brain and its relation to spontaneous resting-state activity. J. Neurosci. 35, 13927–13942 (2015).

Tian, Y. et al. Theoretical foundations of studying criticality in the brain. Netw. Neurosci. 6, 1148–1185 (2022).

Long, X. et al. The restorative effects of outdoor soundscapes in nursing homes for elderly individuals. Build. Environ. 242 (2023).

Liu, F. & Kang, J. Relationship between street scale and subjective assessment of audio-visual environment comfort based on 3D virtual reality and dual-channel acoustic tests. Build. Environ. 129, 35–45 (2018).

Li, Z., Ba, M. & Kang, J. Measuring soundscape quality of urban environments using physiological indicators: construction of physiological assessment dimensions and comparison with subjective dimensions. Build. Environ. (2024).

Shu, S. & Ma, H. Restorative effects of classroom soundscapes on children’s cognitive performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 16 (2019).

Lau, S. Code for Design of Sound Insulation of Civil Buildings GB 50118 – 2010 (China Architecture & Building, 2010).

Dong, X. et al. Effect of thermal, acoustic, and lighting environment in underground space on human comfort and work efficiency: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 786 (2021).

Stansfeld, S. et al. Road traffic noise, noise sensitivity, noise annoyance, psychological and physical health and mortality. Environ. Health. 20, 1–15 (2021).

Cantuaria, M. L. et al. Residential exposure to transportation noise in Denmark and incidence of dementia: National cohort study. BMJ 374 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. The effects of indoor plants and traffic noise on english reading comprehension of Chinese university students in home offices. Front. Psychol. 13, 1003268 (2022).

Yılmaz, M., Kayançiçek, H. & Çekici, Y. Heart rate variability: highlights from hidden signals. J. Integr. Cardiol. 4, 1–8 (2018).

Shiga, K. et al. Subjective well-being and month-long LF/HF ratio among desk workers. PLoS One. 16, e0257062 (2021).

Mizuno, K. et al. Mental fatigue caused by prolonged cognitive load associated with sympathetic hyperactivity. Behav. Brain Funct. 7, 1–7 (2011).

Sanei, S. & Chambers, J. A. EEG Signal Processing (Wiley, 2013).

Soeta, Y., Uetani, S. & Ando, Y. Propagation of repetitive alpha waves over the scalp in relation to subjective preferences for a flickering light. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 46, 41–52 (2002).

Ando, Y. & Chen, C. Y. On the analysis of autocorrelation function of α-waves on the left and right cerebral hemispheres in relation to the delay time of single sound reflection. J. Archit. Plan. 61, 67–73 (1996).

Soeta, Y., Uetani, S. & Ando, Y. Relationship between subjective preference and alpha-wave activity in relation to Temporal frequency and mean luminance of a flickering light. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A. 19, 289–294 (2002).

Massobrio, P. et al. Criticality as a signature of healthy neural systems. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 9 (2015).

Marshall, N. J. et al. Analysis of power laws, shape collapses, and neural complexity: new techniques and MATLAB support via the NCC toolbox. Front. Physiol. 7 (2016).

ASHRAE S. Thermal environmental conditions for human occupancy. ASHRAE Standard 55 F. (1992).

Lan, L. & Lian, Z. Application of statistical power analysis – How to determine the right sample size in human health, comfort and productivity research. Build. Environ. 45, 1202–1213 (2010).

Mukaka, M. Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation in medical research. Malawi Med. J. 24, 69–71 (2012).

Hsieh, C. H. et al. The effect of water sound level in virtual reality: A study of restorative benefits in young adults through immersive natural environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 88 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Using the EEG + VR + LEC evaluation method to explore the combined influence of temperature and Spatial openness on the physiological recovery of post-disaster populations. Build. Environ. 243 (2023).

Stobbe, E., Lorenz, R. C. & Kühn, S. On how natural and urban soundscapes alter brain activity during cognitive performance. J. Environ. Psychol. 91 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Investigating the effect of indoor thermal environment on occupants’ mental workload and task performance using electroencephalogram. Build. Environ. 158, 120–132 (2019).

Zhang, L. & Ma, H. The effects of environmental noise on children’s cognitive performance and annoyance. Appl. Acoust. 198 (2022).

Park, S. H., Lee, P. J. & Jeong, J. H. Effects of noise sensitivity on Psychophysiological responses to Building noise. Build. Environ. 136, 302–311 (2018).

Castaldo, R. et al. Acute mental stress assessment via short-term HRV analysis in healthy adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 18, 370–377 (2015).

Li, J. et al. Improving informational-attentional masking of water sound on traffic noise by Spatial variation settings: an in situ study with brain activity measurements. Appl. Acoust. 218 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. Correlation between brain activity and comfort at different illuminances based on electroencephalogram signals during reading. Build. Environ. 111694 (2024).

Ljung, R., Israelsson, K. & Hygge, S. Speech intelligibility and recall of spoken material heard at different signal-to-noise ratios and the role played by working memory capacity. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 27, 198–203 (2013).

Mather, M. & Nesmith, K. Arousal-enhanced location memory for pictures. J. Mem. Lang. 58, 449–464 (2008).

Park, B. J. et al. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 15, 18–26 (2010).

Gladwell, V. et al. The effects of views of nature on autonomic control. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 112, 3379–3386 (2012).

Thayer, J. F. & Lane, R. D. Claude Bernard and the heart–brain connection: further elaboration of a model of neurovisceral integration. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 33, 81–88 (2009).

Meng, Q. et al. Effects of the musical sound environment on communicating emotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17 (2020).

Liu, G. et al. Stress recovery at home: effects of the indoor visual and auditory stimuli in buildings. Build. Environ. 244 (2023).

Zhang, N. et al. Effects of traffic noise on the Psychophysiological responses of college students: an EEG study. Build. Environ. 267 (2025).

Zhang, N. et al. Effects of spring water sounds on Psychophysiological responses in college students: an EEG study. Appl. Acoust. 228 (2025).

Gullett, N. et al. Heart rate variability (HRV) as a way to understand associations between the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and affective States: A critical review of the literature. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 192, 35–42 (2023).

Ehrhart, J. et al. Alpha activity and cardiac correlates: three types of relationships during nocturnal sleep. Clin. Neurophysiol. 111, 940–946 (2000).

Hahad, O. et al. Cerebral consequences of environmental noise exposure. Environ. Int. 165 (2022).

Beutel, M. E. et al. Noise annoyance is associated with depression and anxiety in the general population—The contribution of aircraft noise. PLoS One 11 (2016).

Beutel, M. E. et al. Noise annoyance predicts symptoms of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance five years later: findings from the Gutenberg health study. Eur. J. Public. Health (2020).

Harmon-Jones, E., Gable, P. A. & Peterson, C. K. The role of asymmetric frontal cortical activity in emotion-related phenomena: A review and update. Biol. Psychol. 84, 451–462 (2010).

Aftanas, L. I. & Golocheikine, S. A. Human anterior and frontal midline theta and lower alpha reflect emotionally positive state and internalized attention: High-resolution EEG investigation of meditation. Neurosci. Lett. 310, 57–60 (2001).

Musacchia, G. & Schroeder, C. E. Neuronal mechanisms, response dynamics, and perceptual functions of multisensory interactions in auditory cortex. Hear. Res. 258, 72–79 (2009).

Ma, X. et al. Relationships between EEG and thermal comfort of elderly adults in outdoor open spaces. Build. Environ. 235 (2023).

Liu, H., He, H. & Qin, J. Does background sound distort concentration and verbal reasoning performance in open-plan offices? Appl. Acoust. 172 (2021).

Frescura, A. & Lee, P. J. Emotions and physiological responses elicited by neighbors’ sounds in wooden residential buildings. Build. Environ. 210 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Innovation Institute for Sustainable Maritime Architecture Research and Technology. We also glad to give our special thanks to all participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Z. and C.L.; methodology, C.L.; software, Q.Y.; validation, R.G. and W.G.; formal analysis, N.Z.; investigation, C.L.; resources, Q.Y.; data curation, X.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Z.; visualization, N.Z.; supervision, W.Y.; project administration, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and ensured that ethical standards were met. Before the experiment began, the researchers explained the purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits of the study in detail to all participants. All participants signed informed consent forms. They had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without facing any negative consequences. All data collected were anonymized to protect the participants’ privacy and data confidentiality.

Informed consent

The consent has been obtained from all study participants for the publication of any identifying information or images (Fig. 1) in an online open-access publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, N., Liu, C., Yuan, Q. et al. Study on the effects of traffic noise and spring water sound at different sound pressure levels on brain dynamic activity. Sci Rep 15, 16670 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96591-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96591-6