Abstract

Bone disorders represent a significant global burden. Currently, animal models are used to develop and screen novel treatments. However, interspecies variations and ethical concerns highlight the need for a more complex 3D bone model. In this study, we developed a simplified in vitro bone-like model using a U-CUP perfusion-based bioreactor system, designed to provide continuous nutrient flow and mechanostimulation through 3D cultures. An immortalized human fetal osteoblastic cell line was seeded on collagen scaffolds and cultured for 21 days in both a perfusion bioreactor system and in static cultures. PrestoBlue™ assay, scanning electron microscopy, and proteomics allowed monitoring of metabolic activity and compared morphological and proteome differences between both conditions. Results indicated an altered cellular morphology in the bioreactor compared to the static cultures and identified a total of 3494 proteins. Of these, 105 proteins exhibited significant upregulation in the static culture, while 86 proteins displayed significant downregulation. Enrichment analyses of these proteins revealed ten significant pathways including epithelial-mesenchymal transition, TNF-alpha signaling via NF-kB, and KRAS pathway. The current data indicated of osteogenic differentiation enhancement within the bioreactor on day 21 compared to static cultures. In conclusion, the U-CUP perfusion bioreactor is beneficial for facilitating osteogenic differentiation in 3D cultures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), bone and joint diseases are the fourth most prevalent global health issue, underscoring the need to understand their pathophysiology and improve their treatments1. One example is osteoporosis, which affects approximately 10.2% of adults over the age of 50, is expected to become more prevalent in the coming years2. Fractures resulting from osteoporosis significantly impact a patients’ quality of life and can be challenging to treat. A common treatment for osteoporosis involves anti-resorptive medication, but this can lead to an adverse event known as medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, which affects the alveolar bone3. Currently, animal models are the golden standard for developing and screening novel treatments for bone-related pathologies. However, these models present several challenges, including ethical concerns, high costs, and need to induce human diseases which may not truly represent the human condition. Furthermore, bone density and turnover differ markedly between animals and humans4.

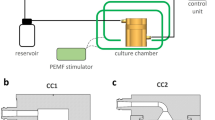

Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine (TERM) offer promising alternatives by mitigating some of the limitations posed by animal models and bridge the gap between clinical and translational research. A key aspect of TERM is the selection of an appropriate tissue engineering environment. While static cultures are widely used, they have limitations such as inefficient cell distribution and poor tissue development. The lack of circulation results in a model of diffusion-based nutrient transport, which limits uniform nutrient distribution5,6. Bioreactors overcome these limitations by providing a circulating environment that delivers nutrients and oxygen to the cells, while removing waste products, thereby promoting more uniform tissue development5,6,7. Additionally, bioreactors allow researchers to control and monitor environmental factors such as the perfusion rate, pH, temperature, and compound supplementation. Various bioreactor systems have been used in bone tissue engineering including spinner flask bioreactors, rotating bioreactors and electromagnetic field-based bioreactor systems. However, these systems have limitations such as unevenly distributed shear stress, poor mineralization effects in outer scaffold regions, and high costs8. Perfusion-based bioreactors emerged as the most suitable for our specific application in bone tissue engineering due to the artificial mechanostimulation and the unique perfusion system they provide9,10. Previous studies have shown that providing mechanical stimulation promotes the development of bone-like structures through various mechanoreceptors and by mimicking muscle forces9,11,12,13,14. This stimulation is particularly beneficial in activating Piezo channels in bone cells, where mechanical stress induces ion flux, enhancing cellular mechanostimulation9. In osteoblasts, Piezo1 channels are responsible for migration while in osteoclasts, it is responsible for the indirect regulation of bone resorption15. In this research, another key motivation for using perfusion-based bioreactors is their compatibility with standard cell culture incubators, making them easily accessible for any laboratory. Besides, the U-shaped bioreactor has been shown to enhance cell seeding efficiency and homogeneous cell distribution16,17.

We used a proteomic-based method to assess the effect of bioreactor perfusion on osteogenic differentiation and to provide an overall proteomic profile. This approach allows for large-scale high-throughput comparative analyses that offers deep insights into mechanistic pathways and key protein regulators18. Compared to studies using transcriptomics, proteomics provides a more accurate representation of the final products of cellular processes19. In this study hFOB1.19 were used due to their osteogenic capabilities and commercial availability which helps standardizing this model20,21. Additionally, Collagen scaffolds were used as collagen is a major component of the bone extracellular matrix (ECM) and has beneficial characteristics such as biocompatibility, low antigenicity, and ability to support the adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of bone cells22,23. The high porosity of these scaffolds also promotes uniform nutrition distribution, which is critical when using a perfusion bioreactor system.

Animal models, though commonly used for such research, have significant limitations and fail to model human biology. We hypothesized that a dynamic perfusion bioreactor would provide an environment that enhances osteogenic differentiation by targeting the involved pathways. Using the commercialized fetal osteoblastic cell line, this standardized model could serve as a globally accessible tool for bone research. Additionally, these cells are pre-programmed for osteoblastic differentiation and do not require added supplements or modifications to the culture environment to induce osteogenic differentiation24. Therefore, this research focuses solely on the effects of perfusion in the U-CUP bioreactor system on osteogenic differentiation. This study aimed to develop a bioreactor model for bone tissue engineering while investigating the molecular basis of this model. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the proteomic basis of osteogenic differentiation within the U-CUP bioreactor system.

Results

Osteoblast metabolic activity and the morphological status in static and bioreactor models

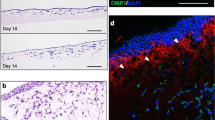

To evaluate the impact of a dynamic environment on the metabolic activity and indirectly the viability of the hFOB1.19 cells in perfusion bioreactor and static cultures, a PrestoBlue assay was performed on days 2, 9, and 16 (Figs. 1, 2A,B). On day 2, the bioreactor cultures showed significantly higher relative cell metabolic activity compared to the static cultures (ratio: 4.18:1, P value = 0.035). However, by day 16, the relative metabolic activity in the bioreactor cultures was significantly lower (ratio: 0.39:1, P value = 0.002). On day 21, the mean cell number from the bioreactor culture (4000) was significantly (P value = 0.027) lower than the mean cell number from the static culture (13 406). The osteoblastic marker alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was quantified in both conditions over the 21-days as a measure of osteogenic differentiation. However, its levels remained constant over time, with no significant differences observed between the groups (Figs. 1, 2C). To analyze the scaffold morphology and assess cell attachment, the samples were examined using SEM. Scaffolds retrieved from the dynamic perfusion bioreactor (Fig. 3A–C) showed fewer cells, which is also supported by the results of cell counting (Fig. 2D, Supplementary table 1) and live/dead staining (Supplementary Fig. 1) on day 21. These cells have a more spread-out and smoothened morphology compared to the more round and scattered morphology in scaffolds from static cultures (Fig. 3D–F).

The results of the PrestoBlue™ metabolic assay, Alkaline phosphatase assay, and cell dissociation results of the bioreactor (n = 4) compared to the static cultures (n = 4). (A) PrestoBlue™ metabolic Assay results. The relative cell viability of bioreactor compared to static cultures are shown. (B) PrestoBlue™ metabolic Assay results. The fluorescence abundance of bioreactor and static cultures are shown. (C) Alkaline Phosphatase Assay results. The mean ALP amount on days 2, 9, 16, and 21 of the bioreactor compared to static culture is shown. (D) Cell Dissociation results. Cell counting results of the bioreactor and static culture on day 21. For all values, the mean and standard deviations are shown. ALP = Alkaline phosphatase, *P value < 0.05.

Scanning Electron Microscopy micrographs of the collagen scaffold with hFOB1.19 cells grown for 21 days in a dynamic perfusion bioreactor system or in a static system (A) An overview of the collagen scaffold in the bioreactor with a magnification of 500×. (Scale bar set at 10 µm) (B) A hFOB1.19 cell in the bioreactor shown with a magnification of 500×. (Scale bar set at 10 µm) (C) hFOB1.19 cells embedded in the collagen scaffold shown in the bioreactor with a magnification of 500×. (Scale bar set at 10 µm) (D) An overview of the collagen scaffold in static conditions with a magnification of 500×. (Scale bar set at 10 µm) (E) hFOB1.19 cells shown in static conditions with a magnification of 500×. (Scale bar set at 10 µm) (F) hFOB1.19 cells embedded in the collagen scaffold shown in static conditions with a magnification of 500×. (Scale bar set at 10 µm).

Proteomic analysis of the differentiation of hFOB1.19 cells in a dynamic VS static bone tissue model

To provide a comprehensive picture of how bioreactors impact the differentiation potential of hFOB1.19, the proteomic changes were analyzed in both bioreactor (n = 4) and static cultures (n = 4). A total of 3494 proteins were identified (Supplementary Table 2). From these identified proteins, 3466 were shared among all samples, with 27 unique to the bioreactor and 1 protein unique to static cultures, respectively. Furthermore, principal component analysis (PCA) plot of proteome profiles projected onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) demonstrated a clear separation between bioreactor and static culture samples. The bioreactor samples (blue) are positioned on the right, while the static culture samples (orange) are positioned on the left, reflecting separation based on PC1 (Fig. 4).

Functional enrichment analysis of differentially abundant proteins

Among the 3466 overlapping proteins, 105 exhibited significant upregulation (Abundance Ratio: (S)/(B) > 0 p adj < 0.05) in static cultures compared to bioreactor cultures, while 86 proteins displayed significant downregulation (Abundance Ratio: (S)/(B) < 0 p adj < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 3). The top ten abundant proteins in bioreactor and static cultures are shown in Table 1. Among them, proteins involved in DNA replication and fibrinolysis, such as HMGA1 and PAI2, were shown to be abundant in bioreactor cultures. In the static cultures proteins associated with apoptosis, including S100A8, HSP76, and LEG7, were abundant.

To elucidate the functional roles of these proteins over-representation analysis (ORA) utilizing the Hallmark database (Table 2, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Table 4). The analysis of the ORA identified “Epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT)”, “TNFA signaling via NF_B”, and “KRAS signaling” as the most significantly regulated pathways with an FDR less than 0.002. Respectively, 19, 11, and 15 proteins were identified in these pathways (Supplementary Table 4). Intriguingly, all three pathways have been previously reported to be associated with osteogenic differentiation or mineralization.

To further understand the interaction between the regulated proteins, a protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis was performed using the String online tool (https://string-db.org), which integrates both known and predicted PPIs (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 5). Active interaction sources and an interaction score > 0.9 were applied to construct the PPI networks. The PPI networks identified few clusters of highly interconnected nodes. The multiple interactions of those proteins enriched in the selected pathways were represented by different color lines. The results showed that 115 of these regulated proteins were from the extracellular region, 110 were from the extracellular space, and 27 were from the ECM which suggests that our bioreactor possibly impacted the ECM (Supplementary Table 6). Three main clusters were identified involved in different biological processes (Fig. 5). The largest cluster involved PPI related to angiogenesis, bone formation, cell adhesion, and motility. The remaining two clusters involved PPI related to protein synthesis and energy metabolism, respectively. Overall, these proteomics results suggest that the bioreactor culture affects the hFOB1.19 cell differentiation by modulating the expression of specific proteins and pathways involved in cell motility and ECM regulation.

Protein–protein interaction analysis and overrepresentation enrichment analysis of the significant proteins. The String online tool was used to gain insights into the interactions and functions of these proteins. Each node is representative of a protein. Red node = extracellular region, purple node = extracellular space, green node = secreted, white node = second shell of interactors, filled node = 3D structure is known or predicted, empty node = unknown 3D structures. Each line represents protein–protein interactions. Light blue and pink interactions refer to known interactions (from databases or experiments). Green, red, and dark blue interactions refer to predicted interactions (gene neighborhood, fusions, and co-occurrence). Yellow line = text mining, black line = co-expression, light purple line = protein homology.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a 3D culture model using hFOB1.19 cells in static and perfusion bioreactor conditions and conducted a comprehensive quantitative proteome analysis. While static cultures are commonly used, they rely heavily on diffusion for nutrient and oxygen delivery, which can negatively impact cell metabolic activity, and indirectly viability over time25. The perfusion provided by the bioreactor was hypothesized to mimic the dynamic bone microenvironment, potentially promoting osteogenic differentiation5,9,10. Our results align with previous findings indicating that osteogenic differentiation requires approximately three weeks26. Consistent with the hFOB1.19 cell line’s characteristics, cell metabolic activity decreased over time in the bioreactor culture compared to the static cultures likely due to an increase in differentiation21. These results suggested that bioreactor cultures provide better nutrient access, although prolonged culturing leads to a reduction in cell metabolic activity. Among the bioreactor cultures, variability was higher in the earlier stages but stabilized over time, while metabolic activity declined after day 9. Importantly, the ALP content remained unchanged, highlighting day 9 as a crucial time point for differentiation. In contrast, the static culture exhibits an increase in metabolic activity, suggesting that in this condition the cells were primarily proliferating rather than differentiating.

SEM imaging qualitative analysis revealed that within the static cultures, cells exhibited a round scattered morphology and were more connected to the scaffold by cell microfilaments. In contrast, cells within the bioreactor cultures exhibited a smoothened and spread-out morphology27,28. Fewer cells are visible in the dynamic bioreactor culture, which could be attributed to osteogenic differentiation as apoptosis is one of the terminal outcomes for osteoblasts29. Furthermore, the involved mechanisms of the bioreactor culture were further elucidated by the top four significantly enriched pathways, as identified through ORA analysis. The most significantly regulated pathway was EMT, a process in which epithelial cells gain mesenchymal characteristics, lose their adhesion structures, and become motile30. In this pathway proteins such as transforming growth factor beta receptor type 3, important for the bone morphogenetic protein signaling pathway and cell migration, were identified31,32. To form bone, it is critical that precursor cells can move to be recruited and to form the correct bone shape33. Past research has shown that EMT promotes osteoblastic differentiation34. Additionally, EMT transcription factors such as ZEB1 and SNAIL can inhibit osteoblastic differentiation, so their downregulation supports differentiation35. In the bioreactor culture, the EMT pathway was downregulated on day 21. Since EMT supports precursor cell motility essential for bone formation, its downregulation at a later stage likely reflects osteogenic differentiation completion33. Two other significantly regulated pathways were TNF-alpha signaling via NFĸB, and KRAS signaling. TNF-alpha promotes osteogenic differentiation by activating the NFĸB pathway, which upregulates osteogenic markers36. Additionally, the NFĸB pathway increases TAZ expression, further enhancing osteogenic differentiation37,38. Past research has shown that the NFĸB pathway can stimulate key osteogenic regulators BMP2, RUNX2, and osterix, and promote mineralization37. While less frequently associated with osteogenic differentiation, the KRAS signaling pathway, involving the small GTPase KRAS, has been identified as an osteogenic regulator influencing ECM accumulation and mineralization 39,40.

Additionally, PPI analysis revealed three primary clusters with patterns among regulated proteins that further support our findings. The largest cluster included proteins associated with angiogenesis such as prostaglandin synthase, fibronectin, and various collagen chains. Proteins related to collagen synthesis, organization, and bone development were also identified, such as fibromodulin and periostin. Other proteins in this cluster were related to cell adhesion, cell motility, and cytoskeleton organization. These biological processes are critical for osteogenic differentiation. Angiogenesis, essential for bone formation by ensuring the supply of nutrients, oxygen, and cells, is stimulated by osteoblasts through their interaction with endothelial cells41. As mentioned, the perfusion in the bioreactor leads to a more uniform distribution of oxygen and nutrients. These results suggest that oxygen tension may be a key factor contributing to the enhancement of osteogenic differentiation. Collagen synthesis and organization are also crucial hallmarks of osteogenic differentiation, with collagen being a predominant protein in the bone ECM42. Osteoid, primarily produced by osteoblastic cells during bone formation, is an unmineralized ECM composed of mainly collagen type 1 and provides a nucleation point for mineralization43. The second-largest cluster involved ribosomal subunit proteins, reflecting the dynamic regulation of ribosome biogenesis during osteoblast differentiation44. The smallest cluster included proteins linked to glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and ATP biosynthesis, highlighting the metabolic demands of osteogenic differentiation45.

When examining the most abundant proteins for both conditions, the bioreactor culture shows SETSIP as the most abundant protein. This protein plays a role in endothelial cell differentiation, which, as previously mentioned, is critical for the osteoblast-endothelial cell communication during angiogenesis. Other abundant proteins in the bioreactor culture are associated with protein synthesis and DNA replication, such as SARNP, SERB1, and HMGA1. DNA replication is essential for the epigenetic regulation, while protein synthesis is integral to cell differentiation, proliferation, and function. Another noteworthy protein in the bioreactor culture is PAI2 or plasminogen activator inhibitor 2, which primarily contributes to fibrinolysis—a process commonly associated with wound healing. However, fibrinolysis also plays a role in bone development and osteogenic differentiation46,47. Following a fracture, fibrinolysis is necessary for breaking down the fibrin clot to aid bone healing. In contrast, the static culture exhibits a different set of abundant proteins. The most abundant protein, S100A8, is a calcium- and zinc-binding protein which has a wide plethora of intra- and extracellular functions. The extracellular functions involve pro-inflammatory, antimicrobial, oxidant-scavenging, and apoptosis-inducing activities48,49. Increased apoptosis is linked to reduced osteogenic potential because the loss of osteoblasts decreases the rate of bone formation50,51. This is supported by the fact that, although the bioreactor culture contained fewer cells, it did not show a decrease in ALP activity. Therefore, these results suggest that osteogenic differentiation progressed more efficiently in the bioreactor culture and most likely resulted in apoptosis. The second most abundant protein, HSP76, is a heat shock protein produced by cells in stressful conditions. Research has shown that heat shock proteins can regulate the osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. However, an overexpression of these proteins may suppress osteogenic differentiation, though this mechanism requires further investigation across different osteogenic precursor cell lines52. Surprisingly, no proteins directly associated with mechanostimulation were identified. However, the proteomic analysis revealed that nine of the regulated proteins are linked to integrin cell surface interactions, as evidenced by the related reactome pathways, highlighting the involvement of mechanical cues.

This study has some limitations that need to be recognized. There was no validation of possible mineralised structures. Future research should address this by incorporating techniques such as Raman spectroscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction analyses to quantify mineralization. This study also did not include calculations or direct measurements of shear stress, or the mechanical properties of the biomaterials involved. Besides, this study provides a snapshot of the involved cultures. In further research, it would be interesting to consider assessing the cell number and expression of osteogenic biomarkers over time. Performing an RT-qPCR would be a valuable tool to, for example, further establish the role of ALP in the bioreactor culture.

As for the implications of our findings, this study establishes a foundational model for advancing bone tissue constructs and research in bone regeneration and remodeling. The U-CUP bioreactor showed promising results by enhancing osteogenic differentiation through the representation of dynamic in vivo-like conditions, which provide improved oxygen and nutrient distribution, as well as mechanical stimulation. Proteomic analysis highlighted non-traditional pathways, such as EMT and KRAS signaling, and identified proteins like SARNP and SERB1 that warrant further exploration. While exploratory, these findings underscore the potential of the U-CUP bioreactor in bone tissue engineering.

Methods

Cell culture

To establish the 3D cell culture, immortalized human fetal osteoblastic cells (hFOB1.19, American Type Culture Collection, Virginia, USA) were used53. These cells were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12, HEPES, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and 0.3 mg/mL Geneticin (G418, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Preparation of the perfusion bioreactor and static cultures

The 3D culture was constructed using collagen sponges (porcine collagen type I, O3D304030, Optimaix, Matricel GmbH)54. Disc-shaped collagen scaffolds with a diameter of 8 mm and a thickness of 3 mm were cut using a disposable biopsy punch (8 mm, KAI medical, Japan). Within the bioreactor system, the scaffolds were embedded within a pair of adaptors inside the bioreactor chamber (UCUP, Cellec Biotek AG, www.cellecbiotek.com, UCUP001). Per scaffold, 1 × 106 hFOB1.19 cells in growth medium were seeded at a velocity of 1000 µm/s overnight using the PHD Ultra Syringe Pump55. The day after, the velocity was changed to 100 µm/s (Fig. 1)55. Furthermore, it was ensured that there were no air pockets or bubbles around the scaffold. For the control groups, referred to as the static culture, the scaffolds were placed in 6-well culture plates and seeded with 1 × 106 hFOB1.19 cells per construct. After 0.5 h, growth medium was added, and the day after, the constructs were moved to new plates and the medium was refreshed. Perfusion and static cultures were maintained for 21 days (37 °C, 5% CO2), with the medium changed every other day. The volume of the medium was the same for both conditions.

PrestoBlue™ metabolic assay

On day 2, 9, and 16 a PrestoBlue™ metabolic assay was performed. Static cultures and bioreactor systems were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 4 h with 10% (v/v) PrestoBlue™ reagent (A13262, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and then 100 µL of the supernatant were harvested from each culture/system. Fluorescence was measured using a CLARIOstar® spectrophotometer (BMG Labtech, Germany) at Ex/Em 560-10/590-10 nm. Cell viability (%) was calculated by dividing the bioreactor’s fluorescence abundance by the static cultures’ fluorescence abundance. The mean value and standard deviation were calculated, the normality was checked, and Welch’s t test was performed using GraphPad.

Alkaline phosphatase assay™

Medium derived from the cultured cell-loaded scaffolds was filtered and used for testing alkaline phosphatase using an Alkaline Phosphatase Assay Kit (Abcam, UK). The samples were diluted with Assay buffer provided with the kit and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 50 mM 4-Methylumbelliferyl Phosphate (MUP) substrate. Samples diluted with Assay buffer and incubated with the stop solution provided with the kit were used to correct for the background signal. The fluorescence of the ALP assay was measured (Ex/Em 360/440 nm) using a CLARIOstar® spectrophotometer (BMG Labtech, Germany). The ALP amount was calculated per sample following the manufacturer’s protocol. The mean value and standard deviation were calculated, the normality was checked, and two-way ANOVA was performed using GraphPad.

Scanning electron microscopy

The collected samples were washed with 1X DPBS (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and fixed using 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The fixed samples were washed in MilliQ water prior to stepwise ethanol dehydration and critical-point-drying using carbon dioxide (Leica EM CPD 030). The samples were mounted on specimen pins using double sided carbon adhesive tabs and sputter coated with a 10 nm layer of platinum (Quorum Q150T ES). SEM images were acquired using an Ultra 55 field emission scanning electron microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) at 5 kV and the SE2 detector.

LIVE/DEAD™ staining

The LIVE/DEAD™ Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit, for mammalian cells (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) was used. The live/dead solution (DPBS, 4 µM Ethidium Homodimer-1, 2 µM Calcein AM) was prepared. The scaffold pieces were incubated in 1 mL live/dead solution for 30 min (37 °C). Using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan) the fluorescence of the live/dead staining was visualized (Ethidium Homodimer-1: Ex/Em 528/617 nm, Calcein AM: Ex/Em 494/517 nm). The results were captured using the NIS elements F software (Nikon, Japan).

Cell dissociation protocol

The collagen scaffold was washed three times with 1X DPBS (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Subsequently, the scaffold was cut into pieces and incubated three times with a trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution (0.25%, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 5 min at 37 °C. After each incubation period, the scaffold was flushed 20 times vigorously using a P1000 pipette, and the suspension was saved in a falcon tube containing three volumes of complete DMEM/F-12. Later, the cell suspension was filtered using a cell strainer (70 µm Nylon, Corning®) to separate the cells from the scaffold debris. The filtered cell suspension was centrifuged at 0.3 g for 5 min. The cell pellet was then collected and placed at − 20 °C for further analyses.

Protein digestion

The cell pellet obtained from perfusion (n = 4) and static cultures (n = 4) was utilized. Proteins were lysed, digested, and purified using the PreOmics SP3-iST kit (PreOmics GmbH, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The only adaptation was the last step of the protein lysis protocol where the samples were spun down, sonicated for 60 s with high-energy sound waves (amplitude 100%, CT, P 0–7 W, C 70%) and spun down again. These peptide extracts were then concentrated using a Speedvac (Thermo Savant SPD121P, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and stored at − 20 °C until further use.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry data acquisition

Peptides obtained from perfusion (n = 4) and static cultures (n = 4) were utilized. Peptides were prepared by reconstituting them in 20 µL of solvent A (2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) and injecting 3 µL onto a 50 cm long EASY-Spray C18 column connected to an Ultimate 3000 nanoUPLC system. This system used a 90-min gradient of solvent B (98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) ranging from 4 to 26% for 90 min, followed by 26–95% for 5 min, and 95% for 5 min at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. The mass spectra were obtained on a Q Exactive HF hybrid quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the range of m/z 375–1800 and at a resolution of R = 120,000 (at m/z 200) targeting 5 × 106 ions for a maximum injection time of 100 ms. This was followed by data-dependent higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) fragmentations of precursor ions with a charge state of 2 + to 8 +, using 45 s dynamic exclusion. The tandem mass spectra of the top 17 precursor ions were acquired with a resolution of R = 30,000, targeting 2 × 105 ions for a maximum injection time of 54 ms, setting the quadrupole isolation width to 1.4 Th and the normalized collision energy to 28%.

Protein quantification

The acquired raw data files were analyzed using Proteome Discoverer v3.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The MS Amanda search engine was used to search against the human protein database (SwissProt taxon ID: 9606 with 20,359 entries, version 2024-03-07). The search parameters included allowing for a maximum of two missed cleavage sites for full tryptic digestion and setting the precursor and fragment ion mass tolerance to 10 ppm and 0.02 Da, respectively. The static modification of carbamidomethylation of cysteine and the dynamic modifications of acetylation on N-termini, oxidation of methionine, and deamidation of asparagine and glutamine were also specified. The initial search results were filtered using the Percolator node in Proteome Discoverer, with a 1% and 5% protein false discovery rate (FDR). Quantification was based on the precursor intensities of unique peptides, and the data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical testing was performed using Proteome Discoverer v3.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the significance was determined using P adjust value (p-adj) < 0.05 as significant.

Bioinformatic analysis

We performed an over-representation enrichment analysis (ORA) using regulated proteins against all identified proteins as a background against on WebGestalt online tool (https https://www.webgestalt.org/, accessed on November 26th, 2024) against the Hallmark database. The top 10 enriched results based on FDR were reported. To gain further insights into the interactions between the significantly regulated proteins, we analyzed protein–protein interactions using the STRING database (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins; http://string-db.org/, accessed on May 10, 2023). The protein–protein interactions were calculated based on experimental evidence, curated database, and predictions based on gene neighborhood, gene fusion, gene co-occurrence, text mining, co-expression, and protein homology.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data were deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD057937.

References

Musculoskeletal health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/musculoskeletal-conditions.

Osteoporosis: Common Questions and Answers | AAFP. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2023/0300/osteoporosis.html.

Ruggiero, S. L. et al. American association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons’ position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the Jaws-2022 update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 80, 920–943 (2022).

Brent, M. B. Pharmaceutical treatment of bone loss: From animal models and drug development to future treatment strategies. Pharmacol. Ther. 244, 108383 (2023).

Gaspar, D. A., Gomide, V. & Monteiro, F. J. The role of perfusion bioreactors in bone tissue engineering. Biomatter 2, 167–175 (2012).

Born, G. et al. Mini- and macro-scale direct perfusion bioreactors with optimized flow for engineering 3D tissues. Biotechnol. J. https://doi.org/10.1002/biot.202200405 (2023).

Dahlin, R. L., Meretoja, V. V., Ni, M., Kasper, F. K. & Mikos, A. G. Design of a high-throughput flow perfusion bioreactor system for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 18, 817–820 (2012).

Rauh, J., Milan, F., Günther, K.-P. & Stiehler, M. Bioreactor systems for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 17, 263–280 (2011).

Woloszyk, A. et al. Influence of the mechanical environment on the engineering of mineralised tissues using human dental pulp stem cells and silk fibroin scaffolds. PLoS ONE 9, e111010 (2014).

Yeatts, A. B. & Fisher, J. P. Bone tissue engineering bioreactors: Dynamic culture and the influence of shear stress. Bone 48, 171–181 (2011).

Damaraju, S., Matyas, J. R., Rancourt, D. E. & Duncan, N. A. The effect of mechanical stimulation on mineralization in differentiating osteoblasts in collagen-I scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part A 20, 3142 (2014).

Papachristou, D. J., Papachroni, K. K., Basdra, E. K. & Papavassiliou, A. G. Signaling networks and transcription factors regulating mechanotransduction in bone. BioEssays 31, 794–804 (2009).

Rosa, N., Simoes, R., Magalhães, F. D. & Marques, A. T. From mechanical stimulus to bone formation: A review. Med. Eng. Phys. 37, 719–728 (2015).

Duda, G. N. et al. Influence of muscle forces on femoral strain distribution. J. Biomech. 31, 841–846 (1998).

Xu, X. et al. Piezo channels: Awesome mechanosensitive structures in cellular mechanotransduction and their role in bone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6429 (2021).

Wendt, D., Marsano, A., Jakob, M., Heberer, M. & Martin, I. Oscillating perfusion of cell suspensions through three-dimensional scaffolds enhances cell seeding efficiency and uniformity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 84, 205–214 (2003).

Saggioro, M. et al. A perfusion-based three-dimensional cell culture system to model alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma pathological features. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36210-4 (2023).

Dadras, M. et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of osteogenic differentiated human adipose tissue and bone marrow-derived stromal cells. J. Cell Mol. Med. 24, 11814–11827 (2020).

Schwanhüusser, B. et al. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473, 337–342 (2011).

Subramaniam, M. et al. Further characterization of human fetal osteoblastic hFOB 1.19 and hFOB/ERα cells: Bone formation in vivo and karyotype analysis using multicolor fluorescent in situ hybridization. J. Cell Biochem. 87, 9–15 (2002).

Oliveira Pinho, F., Pinto Joazeiro, P. & Santos, A. R. Jr. Evaluation of the growth and differentiation of human fetal osteoblasts (hFOB) cells on demineralized bone matrix (DBM). Organogenesis 17, 136–149 (2021).

Glowacki, J. & Mizuno, S. Collagen scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biopolymers 89, 338–344 (2008).

Ferreira, A. M., Gentile, P., Chiono, V. & Ciardelli, G. Collagen for bone tissue regeneration. Acta Biomater. 8, 3191–3200 (2012).

hFOB 1.19 - CRL-3602 | ATCC. https://www.atcc.org/products/crl-3602#product-references.

Schröder, M., Reseland, J. E. & Haugen, H. J. Osteoblasts in a perfusion flow bioreactor—Tissue engineered constructs of TiO2 scaffolds and cells for improved clinical performance. Cells 11, 1995 (2022).

Abou Neel, E. et al. Demineralization–remineralization dynamics in teeth and bone. Int. J. Nanomed. 11, 4743–4763 (2016).

Xynos, I. D. et al. Bioglass ®45S5 stimulates osteoblast turnover and enhances bone formation in vitro: Implications and applications for bone tissue engineering. Calcif. Tissue Int. 67, 321–329 (2000).

Tong, S. et al. In vitro culture of hFOB1.19 osteoblast cells on TGF-β1-SF-CS three-dimensional scaffolds. Mol. Med. Rep. 13, 181–187 (2016).

Ponzetti, M. & Rucci, N. Osteoblast differentiation and signaling: Established concepts and emerging topics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6651 (2021).

Son, H.-J. & Moon, A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cell invasion. Toxicol. Res. 26, 245–252 (2010).

Kirkbride, K. C., Townsend, T. A., Bruinsma, M. W., Barnett, J. V. & Blobe, G. C. Bone morphogenetic proteins signal through the transforming growth factor-β type III receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7628–7637 (2008).

Mythreye, K. & Blobe, G. C. The type III TGF-β receptor regulates epithelial and cancer cell migration through β-arrestin2-mediated activation of Cdc42. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 8221–8226 (2009).

Ichida, M. et al. Changes in cell migration of mesenchymal cells during osteogenic differentiation. FEBS Lett. 585, 4018–4024 (2011).

Bi, F. et al. Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath cells show potential for periodontal complex regeneration. J. Periodontol. 94, 263–276 (2023).

Ruh, M. et al. The EMT transcription factor ZEB1 blocks osteoblastic differentiation in bone development and osteosarcoma. J. Pathol. 254, 199–211 (2021).

Belibasakis, G. N. et al. Gene expression of transcription factor NFATc1 in periodontal diseases. APMIS 119, 167–172 (2011).

Hess, K., Ushmorov, A., Fiedler, J., Brenner, R. E. & Wirth, T. TNFα promotes osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by triggering the NF-κB signaling pathway. Bone 45, 367–376 (2009).

Feng, X. et al. TNF-α triggers osteogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells via the NF-κB signalling pathway. Cell Biol. Int. 37, 1267–1275 (2013).

Yang, Y.-Y. et al. Targeted proteomic profiling revealed roles of small GTPases during osteogenic differentiation. Anal. Chem. 95, 6879–6887 (2023).

Papaioannou, G., Mirzamohammadi, F. & Kobayashi, T. Ras signaling regulates osteoprogenitor cell proliferation and bone formation. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2405–e2405 (2016).

Stegen, S., van Gastel, N. & Carmeliet, G. Bringing new life to damaged bone: The importance of angiogenesis in bone repair and regeneration. Bone 70, 19–27 (2015).

Selvaraj, V., Sekaran, S., Dhanasekaran, A. & Warrier, S. Type 1 collagen: Synthesis, structure and key functions in bone mineralization. Differentiation 136, 100757 (2024).

Florencio-Silva, R., Sasso, G. R. S., Sasso-Cerri, E., Simões, M. J. & Cerri, P. S. Biology of bone tissue: Structure, function, and factors that influence bone cells. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 1–17 (2015).

Neben, C. L., Lay, F. D., Mao, X., Tuzon, C. T. & Merrill, A. E. Ribosome biogenesis is dynamically regulated during osteoblast differentiation. Gene 612, 29–35 (2017).

Shen, L., Hu, G. & Karner, C. M. Bioenergetic metabolism in osteoblast differentiation. Curr. Osteoporos Rep. 20, 53–64 (2022).

Lu, H. et al. Fibrinolysis regulation: A promising approach to promote osteogenesis. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 28, 1192–1208 (2022).

Okada, K., Nishioka, M. & Kaji, H. Roles of fibrinolytic factors in the alterations in bone marrow hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells during bone repair. Inflamm. Regen. 40, 22 (2020).

Zheng, Y. et al. The Pro-apoptotic and pro-inflammatory effects of calprotectin on human periodontal ligament cells. PLoS ONE 9, e110421 (2014).

Yucel, Z. P. K. et al. Salivary biomarkers in the context of gingival inflammation in children with cystic fibrosis. J. Periodontol. 91, 1339–1347 (2020).

Li, S., Meyer, N. P., Quarto, N. & Longaker, M. T. Integration of multiple signaling regulates through apoptosis the differential osteogenic potential of neural crest-derived and mesoderm-derived osteoblasts. PLoS ONE 8, e58610 (2013).

Grellier, M. et al. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in the communication between human osteoprogenitors and endothelial cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 106, 390–398 (2009).

Jin, C., Shuai, T. & Tang, Z. HSPB7 regulates osteogenic differentiation of human adipose derived stem cells via ERK signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 11, 1–13 (2020).

Harris, S. A., Enger, R. J., Riggs, L. B. & Spelsberg, T. C. Development and characterization of a conditionally immortalized human fetal osteoblastic cell line. J. Bone Miner. Res. 10, 178–186 (1995).

Ruoß, M. et al. A standardized collagen-based scaffold improves human hepatocyte shipment and allows metabolic studies over 10 days. Bioengineering (Basel) 5, 86 (2018).

Bao, K., Papadimitropoulos, A., Akgül, B., Belibasakis, G. N. & Bostanci, N. Establishment of an oral infection model resembling the periodontal pocket in a perfusion bioreactor system. Virulence 6, 265–273 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants from Swedish Research Council (2021-03528 to N.B.) and Karolinska Institute’s Strategic funds (N.B.). S.R. was supported by the Erasmus Plus Exchange Funds.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.B., B.K., R.J., D.C. conceived the experiments. S.R., B.K., A.V. conducted the experiments. S.R., B.K., A.V. analyzed the results. S.R. and B.K. performed the writing of the original draft preparation. N.B., B.K., R.J., D.C., M.E. interpreted the results, performed writing, review, and editing. N.B., B.K., R.J., M.E. performed supervision. All authors have read, reviewed, and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The cell line hFOB 1.19 is purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, Virginia, USA (accessioned progeny of ATCC CRL-11372 cited in US Pat. No. 5,681,701).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Radi, S., EzEldeen, M., Végvári, Á. et al. The proteome of osteoblasts in a 3D culture perfusion bioreactor model compared with static conditions. Sci Rep 15, 12120 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96632-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96632-0