Abstract

N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP) is important for diagnosing and predicting heart failure or many other diseases. However, few studies have comprehensively assessed the factors correlated with NT-proBNP levels in people with cardiovascular health. We used data from the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Machine learning was employed to assess 66 factors that associated with NT-proBNP levels, including demographic, anthropometric, lifestyle, biochemical, blood, metabolic, and disease characteristics. The predictive power of the model was assessed using five-fold cross-validation. The optimal features predicting NT-proBNP levels were identified using univariate and step-forward multivariate models. Weighted least squares regression (WLS) was applied for supplementary analysis. Finally, the relationship between the corresponding features and NT-proBNP was validated using weighted and adjusted generalized additive models (GAM). We included 12, 526 participants without cardiovascular diseases. In the univariate model, age exhibited the highest association with NT-proBNP levels (the coefficient of determination (R2) = 36.91%). The multivariate models revealed that age, gender, red blood cell count, race/ethnicity, systolic blood pressure, and total protein level were the top six predictors of NT-proBNP. GAM demonstrated a noteworthy non-linear association between NT-proBNP and age, red blood cell count, systolic blood pressure, and total protein. Our study contributes to explaining the biological mechanisms of NT-proBNP and will facilitate the design of relevant cohort studies. We underscore the significance of assessing various population subgroups when employing NT-proBNP as a biomarker, and the need for developing innovative clinical algorithms to establish personalized levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natriuretic peptides (NPs) are heart-produced hormones, including A-type natriuretic peptide (ANP) and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), utilized as predictive biomarkers for various cardiac diseases, notably heart failure1,2. Elevated BNP and N terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels are linked to increased cardiovascular event and ischemic stroke risks3,4. Moreover, higher NT-proBNP levels are associated with elevated all-cause and cardiovascular mortality5, making it a crucial indicator for diagnosing and predicting cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

In cardiovascular disease, accurately interpreting NT-proBNP levels requires comparison with established normal ranges in non-diseased individuals. This not only necessitates an adequate assessment of the normal range in the general population but also a precise understanding of the factors associated with variations in BNP levels. Research has indicated associations between NT-proBNP levels and variables such as race/ethnicity, age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)5,6. In addition, there is a negative association between NP levels and conditions like dyslipidemia and insulin resistance7. However, these results may vary due to the limited number of variables included, or because they originate from different laboratories. Currently, there is a lack of systematic and comprehensive research evaluating the factors influencing NT-proBNP levels.

Machine learning (ML) offers a powerful tool for data integration and feature selection, addressing the aforementioned issues and providing thorough analysis. Thus, in this study, we utilized data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), and applied ML techniques to comprehensively assess potential factors positively or negatively correlated with NT-proBNP levels in people without cardiovascular diseases. Our aim is to enhance our understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying the variations in NT-proBNP, thereby facilitating clinical decision-making, and optimizing covariate selection in clinical research.

Methods

Study participants

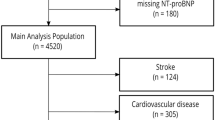

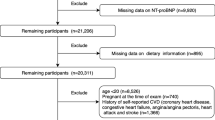

Our study utilized data from the 1999 to 2004 cycles of the NHANES, a representative sample of the U.S. non-institutionalized population’s health and nutritional status, obtained through a multi-stage probability sampling design8,9. It consistently collects demographic and lifestyle information, anthropometric data, current health status, prescription drug use, and indications of clinical examinations and laboratory tests. Our study aims to identify factors associated with NT-proBNP levels in disease-free populations. We only take data from 1999 to 2004 cycles for analysis because only serum specimens in the NHANES 1999–2004 cycles were tested for NT-proBNP. The exclusion criteria10 involved: (1) history of cardiovascular disease (e.g., stroke, coronary heart disease, angina, and “heart attack”. The definitions of these diseases are primarily based on the medical conditions section (prefix MCQ) in NHANES, which provides self-reported data from personal interviews. Participants were asked whether they had ever been diagnosed with these conditions. For example, stroke was defined by the question: “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had a stroke?” Similar definitions apply to the other conditions, using corresponding self-reported responses); (2) heart failure (NT-proBNP concentrations ≥ 450 pg/mL in adults < 50 years old, ≥ 900 pg/mL in adults 50–75 years old, and ≥ 1,800 pg/mL in adults > 75 years old); (3) morbid obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2); (4) pregnancy (women aged 20–44 years who had either a positive laboratory pregnancy test or self-reported pregnancy at the time of the exam, according to the NHANES variable named “RIDEXPRG”). We also eliminated instances of NP deficiencies with NT-proBNP concentrations beneath the weighted 2.5th percentile for each gender and race10. To enhance the performance of our models, we log-transformed the NT-proBNP levels. The procedure of our study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Variable selection and determination

We searched the literature and screened 66 features from the NHANES database for our study (Table S1). These selected features encompassed: (1) demographic factors such as gender, age, and race/ethnicity; (2) anthropometric measures including BMI, height, waist circumference, and blood pressure parameters; (3) lifestyle factors including alcohol consumption, physical activity level, and smoking status; (4) biochemistry test results including serum albumin, alanine aminotransferase, calcium, blood urea nitrogen, total cholesterol, gamma-glutamyl transferase, bicarbonate, total protein, glucose, iron, triglycerides, potassium, uric acid, sodium, osmolality, chloride, globulin, and C-reactive protein; (5) blood test results including white blood cell count, red blood cell count, lymphocyte number, monocyte number, basophil number, neutrophil number, eosinophil number, lymphocyte percent, monocyte percent, eosinophil percent, neutrophil percent, basophil percent, hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean cell hemoglobin concentration, mean cell hemoglobin, mean cell volume, red cell distribution width, mean platelet volume, and platelet count; (6) metabolism test data including c-peptide, insulin, Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, and glycohemoglobin; (7) diseases such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, kidney conditions, asthma, arthritis, hyperlipidemia, emphysema, headaches, chronic bronchitis, liver conditions, cancer, and insulin resistance. Quantitative features were described using the mean and standard deviation (SD), while qualitative features (binary variables) were described using percentages (Table 1). Given that our objective was to pinpoint the biological determinants of NT-proBNP, we deemed it unnecessary to consider social and economic factors.

The detailed description of the variables we selected in NHANES have been documented in an additional table (Table S2).

Statistical analysis

Machine learning model build

We used Scikit-learn (version 1.3.2) based on Python (3.11) to analyze the data. We constructed four machine learning models including MultiLayer Perceptron (MLP), Random Forest, Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). The MLP is a fundamental neural network model comprising numerous layers It includes an input layer, several hidden layers, and an output layer, with each layer composed of multiple neurons. These neurons undergo non-linear transformations to each other through an activation function. Random Forest is an ensemble learning technique that makes predictions using multiple decision trees. Each tree is trained on a random subsample of the dataset. It is suitable for classification and regression tasks, and is especially good at working with nonlinear data. LightGBM is a gradient boosting framework using a histogram-based algorithm optimized for computation efficiency and memory usage. It is mainly used for classification, regression, and ranking tasks, and performs well with large-scale data. XGBoost is also a tree-based gradient boosting framework ensuring accurate and efficient implementation of gradient boosting algorithms. It finds extensive use in classification, regression, ranking, and other machine learning tasks.

We performed hyperparameter tuning using RandomizedSearchCV in sklearn. For instance, in the case of the random forest model, we searched across a range of possible parameter values, including the number of trees (n_estimators: 100–1000), maximum features for splits (max_features: ‘auto’ or ‘sqrt’), maximum tree depth (max_depth: 3–12), minimum samples required to split a node (min_samples_split: 2–11), minimum samples required for leaf nodes (min_samples_leaf: 1–5), and whether to use bootstrap sampling (bootstrap: True or False). The model was trained with 5-fold cross-validation and evaluated using the R2 score. A total of 100 iterations were performed to determine the best combination of parameters. Finally, we selected the best parameters for all four machine learning methods, with the details provided in Supplemental Methods: Settings of Parameters for Four Machine Learning Models.

In building our machine learning models, we used unweighted data from the NHANES because our objective is not to estimate nationwide prevalence rates, but rather to model the relationship between NT-proBNP and selected features for individual subjects11,12. Despite this, considering that the NHANES database employs a multi-stage sampling method, we have incorporated weights in our subsequent weighted least squares (WLS) models and generalized additive models (GAM) to validate the conclusions drawn from our machine learning analysis. We utilize the specific weights developed for measuring NT-pro BNP in NHANES, ‘Cardiac Biomarkers Weights’ (NHANES Variable Name: WTSSCB2Y and WTSSCB4Y), as the weighting factor.

Model evaluation

In this study, we split the entire dataset into training (80%) and test (20%) sets. Within the training set, we performed a fivefold cross-validation, grounded in the Pareto principle (80/20 rule)13, to evaluate model performance14. In this process, each fold acted as a validation set during training. After training, we evaluated the performance of our models using the 20% test data that were not used during the training process.

In our evaluation process, we utilized two metrics, the coefficient of determination (R2) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE), to assess the performance of the four machine learning models, thus determining the most optimal model for downstream analysis. R2 elucidates the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that can be predicted from the independent variable(s) - a perfect model would achieve R2 = 1. On the other hand, MAE quantifies the average magnitude of the differences between the predicted and actual observations.

SHapley additive explanation (SHAP) values

To further elucidate the internal mechanics of our machine learning model, we incorporated the use of SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) values15, which visualized internal mechanics of our model. This approach allowed us to interpret the relationship between the original value of a feature and its subsequent impact on model prediction. The SHAP value measures both the magnitude and direction (positive or negative) of each feature’s contribution to the model’s prediction, visually highlighting the input of each feature to the predicted results. In the context of this study, we inputted all features to observe their effects on model output, and generated a SHAP summary plot for the top 20 features that most significantly influenced the prediction outcomes of the model.

Association between the features and NT-proBNP levels

We commenced the construction of machine learning models employing three strategies: (1) integrating all 66 features into one model; (2) formulating an individual univariate model for each feature; (3) implementing a stepwise forward selection multivariate model. The individual univariate model was built for each feature separately. The univariate predictive value of each feature was determined by calculating their R2 values via five-fold cross-validation. Subsequently, we adopted the stepwise forward selection multivariate model for analysis. In this model, the features with the highest association were initially selected and progressively added one-by-one to fine-tune the model. This process halted once the model met the predetermined criterion - stopping the addition of predictors once the cross-validated R2 improvement failed to exceed zero. This threshold was selected to optimize the precision of the model results.

Complementary analysis was likewise undertaken to calculate the relative effect sizes (alongside 95% Confidence Intervals) of each predictor, as well as the collective association of all predictors to NT-proBNP levels, using WLS. WLS served to assess the directionality of the predictors, determining whether they are positively or negatively associated with NT-proBNP levels. And WLS can allow the inclusion of sampling weights. Then, we conducted the Breusch-Pagan test on both univariable and multivariable models to check for heteroscedasticity in linear regression models. Ultimately, we validated the relationship between the corresponding features and NT-proBNP using the weighted and adjusted GAM. For the GAM model, our goal is to model the nonlinear relationships between the selected features and NT-proBNP. We included six variables in the model: Red.blood.cell.count, Age, Gender, Race, Systolic.blood.pressure, and Total.protein, using the R package mgcv (version 1.8.41). The categorical variables were included as factors, while the continuous variables were modeled with cubic regression splines (bs = “cr”, k = 5). This setup uses cubic regression splines to fit the model, and the remaining parameters are set to the default values of the gam() function in the mgcv package.

For the forward selection process, feature selection is performed using XGBoost regression combined with cross-validation. Two improvement thresholds are defined: a primary threshold of 1% and a secondary threshold of 0.5% to control when to stop adding features. Starting with an empty set of selected features, the algorithm iteratively evaluates each remaining feature by training an XGBoost model with the current set of selected features plus the candidate feature. It performs 5-fold cross-validation to compute the R2 score for each model. The feature that maximizes the R2 score is added to the selected features. This process continues until the improvement in R2 from adding a new feature is smaller than the secondary threshold. Once no further improvement is observed, the process stops, and the final list of selected features, representing the most impactful predictors for the model, is presented. We did not consider multicollinearity issues because machine learning models such as XGBoost and other decision tree-based algorithms are robust to multicollinearity and are generally unaffected by it. This is one of the advantages of using machine learning to identify key features of NT-proBNP.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Upon screening, we selected data of 12, 526 participants from the NHANES database, and organized participant characteristics in Table 1 according to quartiles of NT-proBNP levels. The average age of the study sample was 40.69 years (SD: 21.6), with 50.2% male and 45.5% white participants.

Selection of the machine model

We compared four classes of machine learning algorithms: random forests, XGBoost, MLP, and LightGBM. To evaluate the performance of these models on both the training and testing datasets, we utilized two metrics: R2 and the MAE. Upon the completion of five-fold cross-validation, the XGBoost model emerged superior in the training data, exhibiting a high R2 (0.530), and the lowest MAE (0.580) for testing data (Figure S1). An examination of the scatterplot revealed the data points to be densely packed around the diagonal axis, illustrating the tight association between actual values and those predicted by the model (Figure S2). Consequently, XGBoost was selected for subsequent downstream analysis.

Model explainability

The SHAP summary plot elucidated the inner workings of the XGBoost model, offering a visual portrayal of each feature’s role in shaping the model’s decisions. The top 20 determinants impacting the model’s predictions for NT-proBNP were ranked in descending order based on their average effect on the predictions. Notably, age, sex, race/ethnicity, red blood cell count, and systolic blood pressure are the five strongest predictors (Fig. 2A). To identify differences among populations of different age groups, we studied the age-related variations in the associations between other characteristics and NT-proBNP (Fig. 2B). Notably, in individuals under 60 years of age, sex demonstrates a stronger predictive effect on NT-proBNP expression levels. Conversely, the predictive ability of systolic blood pressure becomes more prominent after the age of 60. However, when stratified by sex and race/ethnicity, no variables were identified as influencing NT-proBNP levels across different sexes or racial groups (Figure S3-S4).

SHAP plot showing the features influencing the NT pro-BNP model predictions. (a) SHAP plot of the top 20 most important variables affecting the NT pro-BNP model predictions, with different features in descending order based on the mean SHAP values (Y axis). The X-axis represented the SHAP values, categorized as positive or negative if a feature has a positive or negative relation to NT pro-BNP. Each point reflected the individual’s SHAP value with red and blue, indicating high and low values of the trait, respectively. (b) Heatmap showed the effects of other characteristics on NT pro-BNP across ages, with higher mean absolute SHAP values shown in deeper yellow). A total of 12526 participants were included.

Assessing factors association with NT-proBNP variability

In univariate models, age showed the highest association with BNP levels, followed by systolic blood pressure and red blood cell count (Fig. 3A). Stepwise forward selection of multivariate models was also undertaken (Fig. 3B), where features were progressively added one by one; this began with the feature attributing most to the model, continuing until the stopping criterion was met. All features demonstrating an R2 enhancement to the model are included, with age delivering an R2 increment exceeding 1% (signaled by the red line), and six attributes indicating an R2 surge surpassing 0.5% (designated by the blue line), which are age, gender, red blood cell count, race/ethnicity, systolic blood pressure, and total protein levels.

Univariate and multivariable models assessing the contributions of different features to NT pro-BNP. (a) Separate univariate models were constructed with each feature individually and cross-validated R² values were used to gauge predictive power. (b) Multivariable models used a stepwise forward selection, first selecting and sequentially adding features based on their contributions one by one to refine the model until it met the predefined criteria. The figure showed all the features that contributed more than 0, with those before the red line contributing more than 1%, and those before the blue line more than 0.5%. The size of the circle corresponds to the magnitude of the influence.

We also did univariate and multivariate WLS models, standardized beta coefficients were calculated to obtain estimates of effect size (95% CI), which were used to assess the direction of influence of a given predictor which demonstrated the positive or negative relationships between these variables and NT-proBNP (Fig. 4). In both univariate and multivariate WLS models, age, blood pressure, and race/ethnicity demonstrate a positive correlation with NT-BNP expression levels and are identified as key predictors. Additionally, when all features are considered, several blood cell components, including red blood cell count and hemoglobin concentration, exhibit a positive association with NT-proBNP levels.

Univariate and multivariate associations between candidate predictors and NT-proBNP levels. In univariate (a) and multivariate (b) weighted least squares (WLS) models, standardized beta coefficients were calculated to obtain estimates of effect size (95% CI), which were used to assess the direction of influence of a given predictor. A total of 12,526 participants were included.

We verified the relationship between the first six characteristics and NT pro-BNP by the GAM (Fig. 5). Using GAM, we illustrated the significant nonlinear relationships between NT-proBNP and variables such as age, red blood cell count, systolic blood pressure, and total protein. Moreover, we identified the impacts of gender and race/ethnicity on NT-proBNP levels, consistent with the SHAP plot (Fig. 2A) and previous study. NT-proBNP levels are associated with age, and this association is more pronounced in White individuals and females. Additionally, within a certain range, NT-proBNP levels are negatively correlated with cell counts and total protein levels, while positively correlated with systolic blood pressure.

Generalized Additive Model (GAM) validated the relationship between the top features and NT-proBNP. (a) Adjusted relationship of age with logNT-proBNP varied by race and gender. NT pro-BNP values gradually increased with Age, more significant in male white people. (b) The adjusted relationship between red blood cell counts and logNT-proBNP showed that NT pro-BNP levels were negatively related to red blood cell count over a range. This trend was also found in (c) Higher systolic blood pressure correlated with elevated NT pro-BNP levels. (d) The relationship between total protein and NT-proBNP. A total of 12,526 participants were included.

Discussion

In this study, we utilized machine learning methods to explore the factors associated with NT-proBNP levels in a representative sample of noninstitutionalized individuals with cardiovascular health in the United States. Previous research that has predominantly focused on using BNP or NT-proBNP for disease-related prediction, but there is a scarcity of studies examining the determinants of NT-proBNP in populations without cardiovascular diseases. By employing machine learning techniques, we aimed to identify the key predictors of NT-proBNP levels in individuals with cardiovascular health in the United States.

We examined a total of 66 potential predictors, considering both individual factors and their collective influence in a multivariate context. Similar to previous research16, We did not include social and economic factors in our analyses because in this study we focused only on the association of biological factors with NT pro-BNP. Our results revealed that age, gender, race/ethnicity, red blood cell count, systolic blood pressure, and total protein were the six most significant factors that predict NT-proBNP levels in individuals without heart failure or related diseases. These findings will contribute to the refinement of the diagnostic criteria for NT-proBNP in cardiovascular disorders and highlight the need for further research in this field.

Several previous studies have identified the relationship between demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and race and NT-proBNP. However, the demographic parameters selected for analysis or stratification were mostly based on experience or random selection17,18,19,20. In this study, we utilized multivariable cross-validation to demonstrate that demographic factors, including age, sex, and race/ethnicity, are the most relevant factors associated with circulating NT-proBNP levels, which means those factors are the most significant predictors of circulating NT-proBNP levels. The association between age and NT-proBNP is strong, accounting for 37.3% of the variance, which exceeds the combined association of all other included factors. Notably, the relationship between age and NT-proBNP was non-linear, with NT-proBNP concentrations displaying a U-shaped distribution across different ages. Specifically, NT-proBNP levels exhibit a negative association with age in younger individuals (SHAP value < 0), whereas in older individuals, they show a positive association with age (SHAP value > 0). This finding corroborated a recent study10. Additionally, the combined association of age and gender with NT-proBNP was 43.5%. Females consistently exhibited higher NT-proBNP levels than males across all age groups, aligning with several prior studies10,18,20. In addition, akin to the research that well recognized the relationship between race and NT-proBNP levels, our study also found that white individuals typically have higher NT-proBNP levels than non-white individuals, respectively21,22. Such racial differences may be caused by genetic variations, and result in increased susceptibility to cardiovascular risk factors and diseases in specific races23.

The strength of our study, in contrast to previous research, lied in the use of a comprehensive machine learning approach to explore the association been 66 features from the NHANES database with the level of NT-proBNP, including demographic characteristics, blood biomarkers, and disease indicators. This method identified age and sex as the factors most strongly associated with NT-proBNP levels. The underlying reasons for age and gender differences in NT-proBNP remain uncertain. Previous studies have suggested that these differences might be related to sex hormones24,25,26, age-related renal, and non-renal NP clearance27, and the heterogeneity of endogenous NP antagonists, such as renin28. Further research is needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms.

Additionally, we found that red blood cell count ranked as the third most associated factor with circulating NT-proBNP in the multivariable cross-validation model. Studies on the association between red blood cell counts and (NT-pro) BNP has not been well founded. In this study, we found that NT-proBNP levels were negatively associated with red blood cell count (EDF = 3.354, P < 2e-16). Earlier investigations have indicated that NT-proBNP levels typically rise in individuals with anemia or hyperhemoglobinemia29,30. A reduction in hemoglobin (Hb) could adversely influence left ventricular function due to the advent of anemia-associated hemodynamic adjustments, which could instigate an increase in NT-proBNP production by cardiomyocytes; notably, this association is independent of age29. To date, no research has explored the association between red blood cell count and circulating NT-proBNP. Although generally, red blood cell counts correspond to Hb levels, notwithstanding potential variances. Interestingly, across all our machine learning analyses, red blood cell count showed a significant association with NT-proBNP in both multivariable cross-validation and univariate models. In the multivariable cross-validation model, its association ranked second only to age and sex, exceeding that of race/ethnicity.

Systolic blood pressure constitutes a vital predictor of BNP levels. NT-proBNP levels were negatively correlated with the systolic pressure below 120 mmHg, but positively associated with the systolic pressure exceeded 120 mmHg. NT-proBNP production is mainly triggered by increased stress on the left ventricular wall, so a higher systolic pressure also results in increased NT-proBNP release. We found that this association also varied with age; it is more pronounced in individuals over 60, with no such variation found between groups of different gender or races. Our study also found that within a certain range of total protein (≤ 9 g/dl), NT-proBNP levels are negatively correlated with total protein levels. (EDF = 3.566, P < 2e-16). Clinical trials have shown that long-term high-dose albumin therapy can normalize serum albumin levels, improve circulation stability and left ventricular function, suggesting a link between protein levels and NT-proBNP31.

In our univariate model, we assessed individual variables, and found that diseases such as arthritis, cancer, and emphysema correlated to the variability in NT-proBNP levels. However, when using a forward selection approach to filter out predictors with a nonzero R2 contribution, the aforementioned diseases were not identified. This discrepancy arises because the apparent contributions in the univariate model may be non-independent, which are replaced by truly significant predictors in the multivariate model.

In our stepwise multivariate model, we identified additional indicators that contributed positively to the R2 value, albeit less significantly than the top six indicators. These indicators include various physiological functions: metabolic-related markers like insulin and total cholesterol, indicating glucose metabolism and lipid levels; renal function markers such as blood urea nitrogen and bicarbonate, reflecting waste excretion and acid-base balance; inflammatory and immune function markers including lymphocyte percentage and C-reactive protein, which show the activity of the immune system and inflammatory status; liver function indicators such as alanine aminotransferase; and others like calcium and mean platelet volume, related to electrolyte balance and blood components. These results suggest that the role of characteristics other than age needs to be considered when interpreting NT-proBNP levels in a broader context.

Ventricular-derived NT-proBNP is associated with the extent of cardiac dysfunction. Its clinical applications include the diagnosis, exclusion, assessment, detection, treatment, and prognostic prediction of heart failure, as well as risk stratification for diseases like pulmonary embolism32. Recent research suggested that BNP and NT-proBNP levels reflected changes in the brain-heart33 and brain-kidney34 axis, and has been now used not only to diagnose heart failure, but also to assess and monitor the prognosis of ischemic stroke, end-stage renal disease, neocoronary syndrome, cancer, and other diseases. Although other studies have attempted to integrate different types of data to predict NT-proBNP, there are no studies systematically assessing the factors affecting NT-proBNP under physiological conditions, and evaluating their contributions. So, existing studies frequently fail to adjust appropriately for confounders or population stratification. This oversight can potentially skew the results in both prospective and retrospective clinical cohort studies.

In this study, we used an ML approach to perform a comprehensive series of analysis to explain the multifactorial nature of NT-proBNP. Cohort studies that incorporate these confounding factors could potentially delve deeper into the factors that influence NT-proBNP, and its implications on diagnosis or prognosis, among other outcomes. In addition, our research suggested that although NT-proBNP is widely used as an indicator of cardiac function in clinical practice, it should not only dictate the assessment of cardiac function in individuals of different ages, genders, and baseline physical conditions, but rather advocate tailored, precise medical treatment.

Our findings can be applied to the following three aspects in the future: (1) To develop individualized diagnostic strategies for heart failure. Current diagnostic criteria for heart failure have taken into account the important association of factors such as age with NT-pro BNP by using age-specific thresholds to diagnose or exclude acute heart failure35. However, other factors, like sex, blood pressure, race/ethnicity and blood cell count, have not been adequately considered. There are many questions that need to be addressed in the future. For example, are the diagnostic cut-off values identical across different racial or gender groups? Are the thresholds for diagnosing heart failure reliable for individuals with varying blood pressures or red blood cell counts? Furthermore, since conditions such as obesity, renal insufficiency, and lung disease are known to correlate with NT-proBNP expression, what NT-proBNP level can reliably indicate heart failure in individuals with these comorbidities? How can we minimize false negatives or false positives? To address these challenges, future research should integrate artificial intelligence technologies with multi-center, large-sample cohort studies conducted across diverse countries, regions, and racial/ethnic groups to explore truly individualized diagnostic strategies based on NT-proBNP levels. (2) Prediction of populations at risk for certain diseases based on NT-proBNP as a predictive marker. Studies have demonstrated that even a slight increase in NT-proBNP can predict the future risk of heart failure in asymptomatic individuals36. Measuring NT-proBNP levels in individuals without heart failure provides valuable insights for risk stratification, enabling the identification of those at the highest risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and most likely to benefit from intensified risk-reduction strategies. Additionally, numerous studies have confirmed that NT-proBNP is a significant marker for the occurrence or prognosis of conditions such as stroke37, respiratory diseases38, and kidney diseases39. Future research should focus on screening NT-proBNP levels across diverse populations and conducting large-scale cohort studies to elucidate its predictive value in preclinical stages of disease. This approach could aid in identifying high-risk populations and facilitating early intervention. (3) Guiding Individualized Treatment for Various Diseases, Including Heart Failure. The BATTLESCARRED (NT-proBNP-Assisted Treatment to Lessen Serial Cardiac Readmissions and Death) trial demonstrated that NT-proBNP-guided therapy significantly reduces long-term mortality in patients aged ≤ 75 years40. Similarly, the PRIMA II trial (Can NT-ProBNP-Guided Therapy During Hospital Admission for Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Reduce Mortality and Readmissions? ) found that, in hospitalized patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), targeting a reduction in NT-proBNP levels by ≥ 30% significantly increased the proportion of patients with stable cardiac function at discharge41. These findings suggest that NT-proBNP-guided treatment can provide substantial benefits to patients. However, due to biological variability—where NT-proBNP levels are influenced by factors such as age, sex, renal function, and obesity—future research should focus on developing multi-indicator models that combine NT-proBNP levels with other biomarkers. Additionally, long-term follow-up studies are needed to assess the sustained benefits of NT-proBNP-guided treatment across different patient subgroups.

Of course, our study has several limitations: (1) our data are cross-sectional, and do not allow for causal inferences. The relationship between features and Nt-pro BNP may be bidirectional, and there may also be complex interactions between multiple factors; we can only explain the magnitude of the association. (2) Our study was also limited to assessing individual NT-proBNP concentrations at a single time point rather than longitudinal changes over time; the factors that influence changes in NT-proBNP concentrations remain unknown; (3) The scope of screened indicators is limited, accounting for only half of the NT-proBNP variations. Future investigations should incorporate additional factors, such as genomic indicators, to enhance explanatory power; (4) We used self-reported diagnoses, among other metrics, to delineate the inclusion criteria. This approach may have resulted in the exclusion of participants with undiagnosed diseases; (5) social and economic factors have been demonstrated to be associated with the development of cardiovascular disease42 or with the expression of BNP43. However, our study exclusively considered biological factors, which may have overlooked the synergistic or interactive effects of social factors with biological factors. This also explains why the FEATURES we included were not sufficient to fully explain the variation in NT-PRO BNP, i.e., we omitted certain influential features, which requires further exploration in future studies; (6) While our study employed internal cross-validation, validation using an external independent cohort would further enhance the robustness of its findings. Future work will focus on validating these conclusions through studies with single-center or multi-center cohorts. Additionally, further studies are needed to investigate the significance and practical application of NT-proBNP expression predictors under physiological conditions for the precise diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases or other diseases.

In conclusion, our results highlight the importance of evaluating different population subgroups when using NT-proBNP as a diagnostic biomarker. In the future, novel statistical methods and clinical algorithms may be essential to determine personalized levels, thereby improving the accuracy of this important clinical parameter for identifying patients at risk and optimizing diagnostic procedures.

Data availability

The data can be accessed publicly at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm, and the programming code can be obtained by sending a reasonable request to the corresponding author’s email.

Abbreviations

- NP:

-

Natriuretic peptides

- ANP:

-

A-type natriuretic peptide

- BNP:

-

B-type natriuretic peptide

- NT-proBNP:

-

N terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- eGFR:

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- MLP:

-

MultiLayer perceptron

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- SHAP:

-

SHapley additive explanation

- WLS:

-

Weighted least squares regression

- GAM:

-

Generalized additive model

- R2 :

-

R-square, the coefficient of determination

- LightGBM:

-

Light Gradient Boosting Machine

- XGBoost:

-

eXtreme Gradient Boosting

- the BATTLESCARRED:

-

NT-proBNP-Assisted Treatment to Lessen Serial Cardiac Readmissions and Death trial

- the PRIMA II trial:

-

Can NT-ProBNP-Guided Therapy During Hospital Admission for Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Reduce Mortality and Readmissions? Trail

- ADHF:

-

Acute decompensated heart failure

References

Naruse, M. et al. Atrial and brain natriuretic peptides in cardiovascular diseases. Hypertens. (Dallas Tex: 1979). 23 (1 Suppl), I231–I234. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.23.1_suppl.i231 (1994).

Chow, S. L. et al. Role of biomarkers for the prevention, assessment, and management of heart failure: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 135 (22), e1054–e91. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000490 (2017).

Rodríguez-Yáñez, M. et al. High serum levels of pro-brain natriuretic peptide (pro BNP) identify cardioembolic origin in undetermined stroke. Dis. Markers. 26 (4), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.3233/dma-2009-0630 (2009).

Chaudhuri, J. R., Sharma, V. K., Mridula, K. R., Balaraju, B. & Bandaru, V. C. Association of plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels in acute ischemic stroke subtypes and outcome. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 24 (2), 485–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.09.025 (2015).

Bajaj, N. S. et al. Racial differences in plasma levels of N-terminal Pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and outcomes: the reasons for geographic and Racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. JAMA Cardiol. 3 (1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4207 (2018).

Patel, N. et al. Race-based demographic, anthropometric and clinical correlates of N-terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide. Int. J. Cardiol. 286, 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.02.034 (2019).

Sanchez, O. A. et al. The associations between metabolic variables and NT-proBNP are blunted at pathological ranges: the Multi-Ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Metabolism 63 (4), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2013.11.017 (2014).

Kalra, R. et al. Increased awareness, inadequate treatment, and poor control of cardiovascular risk factors in American young adults: 2005–2016. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 28 (3), 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487320905190 (2021).

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2023 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 147 (8), e93–e621. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000001123 (2023).

Shetty, N. S. et al. Natriuretic peptide normative levels and deficiency: the National health and nutrition examination survey. JACC Heart Fail. 12 (1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2023.07.018 (2024).

Tsai, S. F., Yang, C. T., Liu, W. J. & Lee, C. L. Development and validation of an insulin resistance model for a population without diabetes mellitus and its clinical implication: a prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 58, 101934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101934 (2023).

Bernard, D. et al. Explainable machine learning framework to predict personalized physiological aging. Aging Cell. 22 (8), e13872. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13872 (2023).

Tanabe, K. Pareto’s 80/20 rule and the Gaussian distribution. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. its Appl. 510 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2018.07.023 (2018). :635 – 40.

Newman, M. E. J. Power laws, Pareto distributions and Zipf’s law. Contemp. Phys. 46 (5), 323–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107510500052444 (2005).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global Understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2 (1), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0138-9 (2020).

Fitzgerald, K. C. et al. Contributors to serum NfL levels in people without neurologic disease. Ann. Neurol. 92 (4), 688–698. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.26446 (2022).

Gupta, D. K., de Lemos, J. A., Ayers, C. R., Berry, J. D. & Wang, T. J. Racial differences in natriuretic peptide levels: the Dallas heart study. JACC Heart Fail. 3 (7), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2015.02.008 (2015).

Braisch, U. et al. N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide reference values in community-dwelling older adults. ESC Heart Fail. 9 (3), 1703–1712. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.13834 (2022).

Greene, D. N. et al. Distribution of High-Sensitivity cardiac troponin and N-Terminal Pro-Brain natriuretic peptide in healthy transgender people. JAMA Cardiol. 7 (11), 1170–1174. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.3299 (2022).

Mu, S. et al. NT-proBNP reference intervals in healthy U.S. Children, adolescents, and adults. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 8 (4), 700–712. https://doi.org/10.1093/jalm/jfad024 (2023).

Fradley, M. G. et al. Reference limits for N-terminal-pro-B-type natriuretic peptide in healthy individuals (from the Framingham heart Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 108 (9), 1341–1345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.06.057 (2011).

Gupta, D. K. et al. Racial differences in Circulating natriuretic peptide levels: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J. Am. Heart Association. 4 (5). https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.115.001831 (2015).

Wang, T. J. et al. Heritability and genetic linkage of plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation 108 (1), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.Cir.0000081657.83724.A7 (2003).

Chang, A. Y. et al. Associations among androgens, estrogens, and natriuretic peptides in young women: observations from the Dallas heart study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49 (1), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.040 (2007).

Saenger, A. K., Dalenberg, D. A., Bryant, S. C., Grebe, S. K. & Jaffe, A. S. Pediatric brain natriuretic peptide concentrations vary with age and sex and appear to be modulated by testosterone. Clin. Chem. 55 (10), 1869–1875. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2009.123778 (2009).

Lam, C. S. et al. Influence of sex and hormone status on circulating natriuretic peptides. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 58 (6), 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.042 (2011).

Wang, T. J. et al. Impact of age and sex on plasma natriuretic peptide levels in healthy adults. Am. J. Cardiol. 90 (3), 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02464-5 (2002).

Parcha, V. et al. Chronobiology of natriuretic peptides and blood pressure in lean and obese individuals. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77 (18), 2291–2303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.03.291 (2021).

Willis, M. S., Lee, E. S. & Grenache, D. G. Effect of anemia on plasma concentrations of NT-proBNP. Clin. Chim. Acta. 358 (1–2), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cccn.2005.03.009 (2005).

Goei, D. et al. The interrelationship between preoperative anemia and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide: the effect on predicting postoperative cardiac outcome in vascular surgery patients. Anesth. Analg. 109 (5), 1403–1408. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b893dd (2009).

Fernández, J. et al. Effects of albumin treatment on systemic and portal hemodynamics and systemic inflammation in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 157(1), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.021 (2019).

Suntharalingam, J. et al. Role of NT-proBNP and 6MWD in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Respir Med. 101 (11), 2254–2262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.027 (2007).

Xu, C., Zheng, A., He, T. & Cao, Z. Brain-Heart axis and biomarkers of cardiac damage and dysfunction after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (7). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072347 (2020).

Liu, M. et al. Cardiovascular-renal axis disorder and acute-phase proteins in cats with congestive heart failure caused by primary cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 34 (3), 1078–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.15757 (2020).

Yancy, C. W. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the heart failure society of America. Circulation 136 (6), e137–e61. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509 (2017).

Kistorp, C. et al. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, C-reactive protein, and urinary albumin levels as predictors of mortality and cardiovascular events in older adults. Jama 293 (13), 1609–1616. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.13.1609 (2005).

Rodríguez-Castro, E. et al. NT-pro-BNP: A novel predictor of stroke risk after transient ischemic attack. Int. J. Cardiol. 298, 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.06.056 (2020).

Adrish, M., Nannaka, V. B., Cano, E. J., Bajantri, B. & Diaz-Fuentes, G. Significance of NT-pro-BNP in acute exacerbation of COPD patients without underlying left ventricular dysfunction. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 12, 1183–1189. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S134953 (2017).

Pfister, R. et al. NT-pro-BNP predicts worsening renal function in patients with chronic systolic heart failure. Intern. Med. J. 41 (6), 467–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02203.x (2011).

Lainchbury, J. G. et al. N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide-guided treatment for chronic heart failure: results from the BATTLESCARRED (NT-proBNP–assisted treatment to lessen serial cardiac readmissions and death) trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55 (1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.095 (2009).

Stienen, S. et al. NT-proBNP (N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide)-guided therapy in acute decompensated heart failure: PRIMA II randomized controlled trial (Can NT-ProBNP-guided therapy during hospital admission for acute decompensated heart failure reduce mortality and readmissions?). Circulation 137 (16), 1671–1683. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.117.029882 (2018).

Bann, D., Wright, L., Hughes, A. & Chaturvedi, N. Socioeconomic inequalities in cardiovascular disease: a causal perspective. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21 (4), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-023-00941-8 (2024).

Matusch, E. et al. Impact of socioeconomic and cardiovascular risk factors on the effect of genetic variants associated with NT-proBNP. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 15560. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19821-1 (2022).

Funding

This research was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LQN25H090017 and the Huzhou Science and Technology Plan Project under Grant No. 2024GYB04 from Ying Liu and the Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Healthcare Science and Technology Plan under Grant No. 2024KY1641 from Bing Zhang. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.ZY., J.XF., and H.H. contributed to study conception and design, interpretation of study data, and drafting of the manuscript. L.Y. led the conceptual design of the study and contributed to data curation, validation, review and editing. N.ZY. and J.XF. contributed to further analysis and revision of the manuscript. M.HG., and L.J. contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the raw study data. Y.XY., and Z.B. contributed to the methodology and validation. Z.B. and L.Y. contributed to the funding resources. All authors had full access to all the data in the study, and were ultimately responsible for the decision to submit it for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used the resources of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a program supported by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and approved by NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (ERB). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Consent for publication

All authors had full access to all the data in the study, and were ultimately responsible for the decision to submit it for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ning, Z., Jiang, X., Huang, H. et al. Machine learning integration of multimodal data identifies key features of circulating NT-proBNP in people without cardiovascular diseases. Sci Rep 15, 12015 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96689-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96689-x