Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) represents a significant public health concern. However, the relationship between MAFLD and different types of respiratory diseases is not yet fully understood. In UK Biobank prospective cohort, 11 types of respiratory diseases were identified according to the ICD-10 codes. Cox regression was used to determine the association between MASLD and respiratory disease risk. A total of 393,416 subjects with an average age of 56.6 years were included, MASLD patients account for 34.9%. After fully adjustment for confounding factors, 9 out of 11 respiratory diseases were significantly associated with MASLD, including influenza (hazard ratio (HR): 1.294), pneumonia (HR: 1.258), chronic lower respiratory diseases (HR: 1.297), asthma (HR: 1.222), lung diseases due to external agents (HR: 1.190), interstitial lung diseases (HR: 1.336), diseases of the pleura (HR: 1.175), pulmonary embolism (HR: 1.225), lung and bronchus cancer (HR: 1.212) and respiratory system death (HR: 1.108) (P < 0.05 for all). The risk of respiratory diseases increases with the severity of MASLD assessed by fibrosis score. The relationship between the MASLD phenotype and respiratory diseases is independent of polygenic risk scores and four related risk alleles. These findings emphasize the value of comprehensive prevention of respiratory diseases by targeting MASLD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Respiratory diseases are a significant global burden, affecting about 500 million adults and having a prevalence of approximately 7.1%1. They are the third leading cause of death worldwide and are responsible for 4 million deaths annually2. Respiratory diseases are systemic and interconnected disorders, and all respiratory disease subtypes are usually attributed to similar risk factors, such as smoking, air pollution, and obesity3. Therefore, identifying key risk factors is critical for the comprehensive prevention of systemic respiratory diseases.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a common chronic liver disease affecting over 25% of the global population4. However, the current definition of NAFLD, which relies on exclusionary criteria and lacks consideration of metabolic factors, has been criticized5,6. The alternative term metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) has also been criticized for stigmatization and the confounding of multiple metabolic and hepatic factors6,7. Recently, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) defined as the presence of steatotic liver disease (SLD) and at least one cardiometabolic risk factor has been proposed8. Associations between MASLD and the cardiovascular system and urinary system have been shown9,10, but the adverse outcomes and disease burden associated with this redefinition are still being investigated.

Several clues have suggested that MASLD may be closely related to systemic respiratory diseases. Metabolic abnormalities including diabetes and obesity are associated with multiple types of respiratory diseases3,11. Besides, it has been proven that NAFLD is associated with pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and lung cancer12,13. Importantly, in our previous studies investigating multisystem diseases and the trajectory of death in MAFLD, respiratory diseases were found to be crucial mediating factors of death, and respiratory system death accounted for approximately 13% of the total death14. Mechanistically, liver diseases, metabolic disorders and respiratory diseases share several pathological processes, including liver-lung axis, gut-liver-lung axis, immune dysfunction, and inflammatory response, oxidative stress15,16.Despite these findings, significant gaps remain in our understanding of the relationship between MASLD and respiratory diseases. Existing studies are often limited by small sample sizes, lack of longitudinal data, and inadequate control for confounding factors. Furthermore, the specific mechanisms underlying the association between MASLD and respiratory diseases are not fully understood. Above all, it is necessary to further confirm the association between NAFLD and systemic respiratory diseases, which could deepen our understanding of the adverse outcomes of MASLD and benefit certain populations by decreasing respiratory disease-related health burdens.

Thus, in this study, we hypothesized that participants with MASLD are at increased risk of all categories of respiratory diseases. Therefore, we aimed to explore the relationship between MASLD and 13 types of respiratory disease according to previous classifications in a large community-based UK Biobank cohort.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 393,416 participants (44.3% males) aged 56.6 ± 8.0 years were included in this study according to the flowchart (Fig. 1). Among them, 137,295 participants were complicated with MASLD. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Males, older individuals, non-white and smokers were more likely to have MASLD (P < 0.05). Compared to non-MASLD participants, MASLD participants had higher waist circumference, BMI, higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension, and liver function index, such as serum triglycerides, serum cholesterol, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma glutamyltransferase, and air pollution levels, but lower FEV1/FVC (P < 0.05).

Relationship between MASLD and respiratory diseases

Compared to those without MASLD, individuals with MASLD had generally higher incidences of respiratory diseases and respiratory death (P < 0.05 for all), including acute upper respiratory infections [968 (0.7%) vs. 1505 (0.6%)], influenza [512 (0.4%) vs. 604 (0.2%)], pneumonia [8078 (5.9%) vs. 8700 (3.4%)], other diseases of the upper respiratory tract[3908 (2.8%) vs. 6196 (2.4%)], chronic lower respiratory diseases [6704 (4.9%) vs. 8111 (3.2%)], asthma [9932 (7.2%) vs. 13416 (5.2%)], lung diseases due to external agents [1114 (0.8%) vs. 1307 (0.5%)], interstitial lung diseases [1399 (1%) vs. 1365 (0.5%)], diseases of the pleura [5059 (3.7%) vs. 6245 (2.4%)], pulmonary embolism [2456 (1.8%) vs. 2549 (1.0%)], lung and bronchus cancer [1474 (1.1%) vs. 2126 (0.8%)], and respiratory system death [598 (0.4%) vs. 817 (0.3%)]. The findings of the Cox regression analysis for MASLD and respiratory diseases are shown in Fig. 2. After fully adjusting for variables involving demographics, physiology, laboratory examination, and chronic medical conditions, 9 out of 11 respiratory diseases were significantly associated with MASLD. They were, in order, influenza (HR 1.294, 95% CI 1.081–1.549, P = 0.005), pneumonia (HR 1.258, 95% CI 1.201–1.317, P < 0.001), chronic lower respiratory disease (HR 1.297, 95% CI 1.235–1.362, P < 0.001), asthma (HR 1.222, 95% CI 1.174–1.273, P < 0.001), lung disease due to external agents (HR 1.190, 95% CI 1.055–1.342, P = 0.005), interstitial lung disease (HR 1.336, 95% CI 1.195–1.494, P < 0.001), disease of the pleura (HR 1.175, 95% CI 1.111–1.243, P < 0.001), pulmonary embolism (HR 1.225, 95% CI 1.126–1.332, P < 0.001), lung and bronchial cancer (HR 1.212, 95% CI 1.095–1.341, P < 0.001 and respiratory system death (HR 1.108, 95% CI 1.036–1.181, P = 0.004). Results of sequentially adjusted models are shown in Table S1. According to the competitive risk models, the relationship between MASLD and respiratory diseases was almost consistent (Fig. 3).

Association between MASLD scores and 11 types of respiratory diseases using Cox regression models. The model was adjusted for sex, age, deprivation index, alcohol intake (g/day), smoking (never, former, current), BMI, diabetes, hypertension, serum triglycerides, serum cholesterol, glucose, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, FEV1/FVC, NO2, NOx, PM2.5, and PM10.

Association between MASLD and 11 types of respiratory diseases using the Gray-Fine sub-distribution hazard model. The model was adjusted for sex, age, deprivation index, alcohol intake (g/day), smoking (never, former, current), BMI, diabetes, hypertension, serum triglycerides, serum cholesterol, glucose, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, FEV1/FVC, NO2, NOx, PM2.5, and PM10.

To explore the relationship between the severity of MASLD and respiratory disease risk, the population was stratified based on NFS. Set non-MASLD group as reference, MASLD participants with high levels of NFS had the largest HR (1.777 (95% CI 1.114–2.835, P = 0.016), 1.738 (95% CI 1.548–1.953, P < 0.001), 1.470 (95% CI 1.279–1.690, P < 0.001), 1.643 (95% CI 1.225–2.205, P = 0.001), 1.430 (95% CI 1.080–1.895, P = 0.013), 1.307 (95% CI 1.018–1.678, P = 0.036), 1.206 (95% CI 0.867–1.677, P = 0.265) and 1.149 (95% CI 0.982–1.315, P = 0.096) (Table 2) for risk of influenza, pneumonia, chronic lower respiratory disease, lung disease due to external agents, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary embolism, lung and bronchus cancer and respiratory system death respectively, compared with lower NFS level. From the overall trend, the risk of respiratory diseases increased with increasing MASLD severity.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

In our subgroup analysis employing adjusted Cox regression analysis, we observed that the association between MASLD and respiratory diseases was statistically significant across various subgroups defined by age, BMI, and sex. Notably, the strength of this association was more pronounced among participants aged ≤ 60 years (Table S2). Overweight or obese individuals with MASLD had higher risk for lung and bronchial cancer (HR 1.21 vs. 1.13), but a lower risk of pneumonia (HR 1.25 vs. 1.38), chronic lower respiratory diseases (HR 1.28 vs. 1.44), asthma (HR 1.26 vs. 1.33), diseases of the pleura (HR 1.15 vs. 1.31), and pulmonary embolism (HR 1.22 vs. 1.53) than normal-weight MASLD (p for interaction < 0.05) (Table S3). The gender subgroup analysis revealed that the risk of all of the 9 respiratory diseases was higher in females with MASLD (Table S4).

According to the sensitivity analyses, after excluding individuals with less than 24 months of follow-up and additionally adjusting for statins, antihypertensive drugs, and hypoglycemic drugs, the relationships between the MASLD and 9 respiratory diseases were consistent (Table S5-S6).

Genetic risk of MASLD and respiratory diseases

Overall, the relationship between MASLD and respiratory diseases was independent of the polygenic risk scores and the four risk alleles (Table S7-S10). The association of MASLD with influenza and lung diseases due to external agents was stronger in participants with high PRS than in those with low-PRS (Fig. 4, P for interaction < 0.05). Among the four risk alleles, MASLD with PNPLA3 rs738409 (C > T) showed significantly larger HR for influenza (HR: 1.376 vs. 1.275) than those without PNPLA3 rs738409, while MBOAT7 rs641738 (C > T) showed significant large HR for interstitial lung diseases (HR: 1.551 vs. 1.274) and pulmonary embolism (HR: 1.503 vs. 1.282) than those without PNPLA3 rs641738.

Discussion

This large-scale prospective cohort study with long-term follow-up was the first to systematically investigate the association between MASLD and multiple respiratory diseases based on the UK Biobank community-dwelling population. In this study, the participants with MASLD had elevated risk rates ranging from 10 to 34% for respiratory disease death and 9 respiratory diseases, including influenza, pneumonia, chronic lower respiratory diseases, asthma, lung diseases due to external agents, interstitial lung diseases, diseases of the pleura, pulmonary embolism, and cancer. However, the relationship between MASLD and acute upper respiratory infections was not significant. These relationships remained consistent after eliminating the competitive risk of death. Thus, our findings emphasized that MASLD may be an important predictor and target of almost all types of respiratory disease.

In subgroup analysis, the association between MASLD and various respiratory diseases appears to be stronger among younger, thinner, and female individuals. Although the prevalence of SLD is currently the highest in the elderly, its prevalence in adolescents and middle-aged adults should not be underestimated17. Younger MASLD patients generally have more pronounced obesity, liver function abnormalities and genetic susceptibility, which may lead to more severe complications18. This is also in accordance with our findings that patients aged < 60 years have a higher risk of developing respiratory diseases. It is noteworthy that women with MASLD are more susceptible to multiple respiratory diseases compared to men. Possible causes include changes in estrogen levels19.

As research has progressed, the concept of a specific type of MASLD, namely lean MASLD, has been proposed. Visceral obesity, poor life habits and genetic risk factors are common in patients with lean MASLD, and those with lean MASLD have been confirmed to have a worse liver status20 Studies show that lean MASLD patients have higher risks of liver-related events21,22 and liver, pancreatic and colorectal cancers23, compared to non-lean MASLD patients. A meta-analysis indicated that the overall mortality risk in lean MASLD patients is 1.6 times higher than in non-lean MASLD patients24. Despite the worse liver outcomes observed in lean MASLD patients, their cardiovascular outcomes were comparable to those of non-lean MASLD patients, underlying clinical management should consider multiple metabolic factors rather than relying solely on body type to assess cardiovascular risk. Similar to common perceptions, our study also revealed that MASLD patients with lower BMIs were at higher risks than those with higher BMI. This phenomenon is unlikely to be coincidental, although a clear and universally accepted cause has yet to be established. However, several potential factors may mediate this phenomenon, including the following possible reasons. While individuals with lean MASLD exhibit a lower degree of metabolic derangements compared to their non-lean counterparts, accumulating evidence indicates that both hepatic inflammation and fibrosis tend to progress more rapidly in lean MASLD patients, which may be attributed to underlying immune dysfunction. Conversely, obese individuals typically experience chronic low-grade inflammation; however, their immune systems may achieve a relative degree of stability through the regulatory effects exerted by adipose tissue25. Besides, individuals with lean MASLD often carry high-risk genes for fatty liver (such as PNPLA3 rs738409 GG and TM6SF2 rs58542926 TT), leading to increased liver cell damage and chronic inflammation, which further elevate the risk of respiratory diseases and mortality26,27. Additionally, the current BMI formula, which fails to effectively differentiate between fat, muscle, and bone composition as well as between subcutaneous and visceral fat, may lead to inaccurate assessments of obesity-related health risks. All of these reasons may result in findings that are counterintuitive or contrary to established assumptions, potentially contributing to the phenomenon known as the “obesity paradox”. This finding also suggested that the relationship between metabolic disorders and respiratory diseases is independent of obesity.

Studies have shown that MASLD-related disease and mortality are correlated with the severity of liver fibrosis28. In the present study, MASLD subjects with higher NFS were also more likely to have higher risk of systemic respiratory disease, except for COPD. This means that only subjects with mild liver disease raise similar risks as severe liver disease. This further emphasizes the significance of MASLD prevention and early intervention.

MASLD progression is influenced by environmental and genetic factors29. Genome-wide association studies have advanced the knowledge of MASLD’s genetic basis, with PNPLA3 being a key gene, and TM6SF2, MBOAT7, and GCKR also playing significant roles30. In this study, association between MASLD and 9 respiratory diseases were independent of genetic risk. Interestingly, the association of MASLD with influenza and lung diseases due to external agents was stronger in participants with high-PRS than those of low-PRS.

Some mechanism may explain the association between MASLD and respiratory diseases. First, the liver plays a crucial role in both innate and adaptive immune responses, which may affect infectious disease development such as influenza and pneumonia31. Second, research shows that MASLD and COPD share common causes like oxidative stress and insulin resistance, and are linked by the gut-liver-lung axis32. The liver-lung axis concept also shows how liver disease can increase lung inflammation through changes in acute-phase proteins33. Third, metabolic disorders, which are common in MASLD patients, increase free fatty acids and insulin resistance, leading to worsened airway inflammation and higher sensitivity34. Fourth, interstitial lung disease, characterized by lung inflammation and fibrosis, shares mechanisms like oxidative stress, ER stress, aberrant autophagy process and lymphocyte infiltration with MASLD, explaining their connection35. The identification of key targets for intervention may contribute to the integrated management of respiratory diseases.

Strength and limitations

This study advances MASLD understanding by evaluating the associations between MASLD and multiple respiratory outcomes, including 11 diseases and mortality, in a large cohort. Particularly, this study leverages the UK Biobank study, with its nationwide recruitment and extensive follow-up data, enables us to access an extensive array of respiratory disease diagnoses and conduct a prospective analysis of the long-term impact of MASLD on respiratory diseases. This approach provides compelling evidence of temporal causality regarding their association. Additionally, the use of polygenic risk scores and whole-genome sequencing data enhances the study’s ability to quantify genetic risk comprehensively and identify high-risk individuals.

-

However, the study is also subject to several limitations. First, the lack of liver biopsy, the diagnostic gold standard for SLD, is a notable limitation due to its impracticality for large cohorts. This may affect the accuracy of SLD diagnosis. Second, the identification of respiratory diseases via ICD codes, although generally accurate, may not capture all cases, potentially leading to underestimation or misclassification. Third, the predominantly European genetic background of the dataset limits the generalizability of the findings to other ethnic groups. Additionally, the homogeneous sample lacks geographic and ethnic diversity, further constraining the external validity of the results. Fourth, potential confounders, such as chronic health conditions and demographic profiles, may not be fully accounted for, which could influence the study outcomes. Fifth, the absence of an external database for validation limits the reproducibility of the study findings. Finally, long-term follow-up, while beneficial for longitudinal analysis, may introduce unadjustable confounding factors, such as the impact of COVID-19.

Conclusion

The present study systematically analyzed the association between MASLD and 11 respiratory diseases. Among these, the risk of 9 respiratory diseases was significantly elevated in individuals with MASLD, according to a large prospective cohort study. The high risk of respiratory diseases associated with MASLD was independent of genetic susceptibility. These findings emphasize the importance of comprehensive prevention and early intervention for respiratory diseases by targeting MASLD. Future research still needs to focus on exploring whether the alleviation or cure of MASLD can mitigate the progression of respiratory diseases and the precise mechanisms.

Methods

Study design and population

Since its inception in 2006, the UK Biobank has effectively garnered a broad participant base from various UK regions, leveraging postal invitations supported by the National Health Service36. The project enlisted 502,655 individuals aged 39 to 69 years from a range of communities between March 13th, 2006 and October 1st, 2010. The research protocol received green light from the North‒West Research Ethics Committee. All subjects provided informed consent in writing, ensuring that the study conformed to the ethical standards set by the Helsinki Declaration. The West China Hospital of Sichuan University’s Human Ethical Committee sanctioned the use of the data (2023 − 1829).

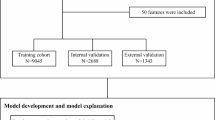

In this study, we initially included 502,897 participants during the baseline visit of the UK Biobank study (2006–2010). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) withdrawal from the study (n = 242); (2) without complete data for MASLD diagnosis (n = 40559); (3) alcoholic or other causes of induced SLD (n = 26100); (4) history of respiratory disease at baseline (n = 42432); and (5) > 20% missing covariates (n = 148). Thus, a total of 393,416 participants were included in our study. To further investigate the influence of genetic factors on the association between MASLD and respiratory disease, individuals with missing genetic data (n = 9,643) were excluded and a sub-cohort was established (n = 383,773) (Fig. 1).

Determination of MASLD

In accordance with the consensus established through a Delphi process among various healthcare organizations, MASLD is characterized by the simultaneous presence of SLD and a minimum of one cardiometabolic hazard, as indicated8: (1) a body mass index equal to or exceeding 25 kg/m2 or a waistline not less than 94 cm for men or 80 cm for women; (2) levels of fasting glucose at or above 5.6 mmol/L or HbA1c surpassing 5.7%, or an established case of type 2 diabetes, or the application of therapies for diabetes management; (3) a blood pressure measurement at or above 130/85 mmHg or the implementation of blood pressure-lowering medications; (4) triglycerides at or over 150 mg/dL or engagement with treatments aimed at reducing lipid levels; and (5) low-density lipoprotein cholesterol falling below 40 mg/dL in males or 50 mg/dL in females or the utilization of medications to reduce lipid levels. The exclusion criteria included individuals exhibiting excessive alcohol consumption (a weekly intake beyond 210 g for men or 140 g for women), those diagnosed with simultaneous liver conditions, or those prescribed drugs known to induce steatosis, including but not limited to methotrexate, amiodarone, glucocorticoids, or tamoxifen.

SLD was characterized through the estimation of the fatty liver index (FLI), taking into account factors such as body mass index, triglyceride levels, gamma-glutamyl transferase readings, and waist circumference measurements. An FLI value of 60 or higher indicated the presence of SLD, demonstrating 87% sensitivity and 86% specificity in diagnosis37. The FLI is recognized as a reliable substitute for liver biopsy and is especially beneficial for use in extensive research studies where invasive methods are impractical38.

Calculation of liver fibrosis scores

To assess the extent of liver fibrosis and thus gauge the intensity of MASLD, the NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS) served as a diagnostic tool. The NFS was calculated using the following formula: NFS = -1.675 + [0.037 × age (years)] + [0.094 × BMI (kg/m2)] + [1.13 × T2D (yes = 1, no = 0)] + [0.99 × AST/ALT ratio] - [0.013 × platelet count (109/L)] - [0.66 × albumin (g/dL)]. The criteria for delineating the severity range from a lower threshold of -1.455 to an upper threshold of 0.676 39.

Genotyping

Genotypic determination and imputation methods were performed via the Axiom and BiLEVE arrays from the UK. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) implicated in GWAS for MASLD (P < 5 × 10− 8), such as rs641738 C > T in MBOAT740 (22-44%)41, rs1260326 T > C in GCKR42 (13-45%)43, rs58542926 T > C in TM6SF244 (6-34%)45, and rs738409 C > G in PNPLA346 (17-42%)43, were included in this analysis. Allelic variants of the SNPs received values of 2 for homozygous, 1 for heterozygous, and 0 for noncarrier statuses of participants. The computation of polygenic risk scores (PRS) utilized the following equation: (β1 × SNP1 + β2 × SNP2 +. + βn × SNPn) × (total count of SNPs/combined β coefficients), with β sourced from initial GWAS data. The β coefficients for each SNP in this study are derived from previously published studies47. This PRS provided insights into an individual’s genetic susceptibility to MASLD. We categorized PRS into groups indicating either low or high genetic susceptibility to the disease.

Outcome

Hospital documentation, which included details on admissions and fatalities from all National Health Service (NHS) institutions across the UK, underwent meticulous categorization following the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) as set out by the World Health Organization. Anonymous numeric codes for participant identification were employed to securely link individuals to their respective records. According to previous reports, the discharge coding accuracy of medical conditions of inpatients in the UK was verified, with a primary diagnosis accuracy of 96% and an average diagnostic accuracy of 80.3%48.

The classification of hospital admission data revealed 14 distinct respiratory system conditions identified in prior research49: acute upper respiratory infections (J00-J06), influenza (J09-J11), pneumonia (J12-J18), other diseases of the upper respiratory tract (J30–J39), chronic lower respiratory diseases (J40-J44, J47), asthma (J45-J46), lung diseases due to external agents (J60-J70), interstitial respiratory diseases (J80-J84), diseases of the pleura (J90-J94), pulmonary embolism (I26), and lung and bronchus cancer (C34). Due to the low incidence (< 0.1%), several respiratory diseases including necrosis of the lower respiratory tract (J85-J86, 0.02%), acute bronchitis (J20, 0.01%), and other respiratory diseases principally affecting the interstitium (J80-J84, 0.01%) were excluded. Finally, a total of 11 types of respiratory diseases and respiratory system death were analysed. The prominent cause of mortality related to respiratory diseases was documented in the UK Biobank dataset (J00-J99).

The follow-up period for each respiratory condition commenced on the participation date within the study and concluded upon the earliest report of the illness, death, or at the termination of the study monitoring (first of November 2023), depending on which occurred first.

Covariate assessment

A number of confounding factors were identified based on existing studies, and information was collected during the initial thorough evaluation at the time of participants’ enrollment in the UK Biobank. We established participant ages by determining the duration from their date of birth until the enrollment date. The Townsend Deprivation Index was used to gauge socioeconomic hardship. We classified smoking history into three categories: non-smokers, ex-smokers, and current smokers. The total alcohol consumption was calculated by tallying the daily average intake across alcoholic beverages. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using measured height and weight. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of ≥ 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 90 mmHg, or the use of antihypertensive medications. Diabetes was defined as a fasting blood glucose level of ≥ 126 mg/dL, a non-fasting blood glucose level of ≥ 200 mg/dL, or the use of hypoglycemic medications. The lung function testing procedures followed the UK Biobank’s manual and involved spirometry conducted by skilled technicians. Participants performed two, occasionally three, six-second blows within roughly six minutes, using the highest valid measurement. Lung function assessments relied on forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and their ratio, with an FEV1/FVC less than 70% indicating impaired lung function50. Data on prescription medications were obtained through a structured verbal interview conducted by a trained nurse. This included detailed information on the type and number of medications taken by participants, with specific categories comprising: statins, antihypertensive drugs and hypoglycemic drugs. The 2010 annual average concentrations of air pollutants, including NO2, nitrogen oxides (NOx), PM2.5, and PM1.0, were estimated using a land use regression (LUR) model developed by the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE) .The methodologies pertaining to the acquisition and analysis of blood specimens have been thoroughly described and corroborated previously51. Comprehensive data on blood biomarkers were obtained from the UK Biobank database, including measurements of glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycosylated hemoglobin, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and glutamyl transpeptidase.

Statistical analysis

Initial data were stratified and presented according to MASLD occurrence and liver fibrosis severity. The medians (25th and 75th percentiles) of nonparametric variables were calculated via the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis H test for statistical comparison. The means ± SDs denote parametric variables, which were assessed using independent sample t tests or one-way ANOVA. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages) and were compared through chi-square tests.

The relationship between MASLD and respiratory diseases was investigated using Cox regression to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A subcohort excluding individuals with a preexisting respiratory condition at baseline was formed to study these specific outcomes. Model 1 was a univariable analysis, Model 2 was adjusted for sex, age, deprivation Index, alcohol intake, smoking, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, and Model 3 was further adjusted for variables including serum triglycerides, serum cholesterol, glucose, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase,, FEV1/FVC, NO2, NOx, PM2.5, and PM10.

To eliminate the competitive risk of death, a Gray-Fine subdistribution hazard model was conducted to evaluate the association between MASLD and 11 respiratory diseases.

Age (≤ 60 vs. >60), sex (female vs. male), and BMI (≥ 25 vs. <25 kg/m2) were used to delineate subgroup differences, as assessed by the Cox regression models referenced above. The analysis incorporated MASLD severity and genetic predisposition. Cox regression models were also used to calculate the risk of respiratory disease across participants with various liver fibrosis scores and PRS, considering those without MASLD as the reference group. A sensitivity analysis was performed using Cox regression models, adjusting for statins, antihypertensive drugs, and hypoglycemic drugs, while omitting individuals with respiratory diagnoses within two years post-enrollment.

P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significance. SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp) and R 3.5.0 were used to conduct the analyses.

Data availability

The data and materials can be obtained at https://ukbiobank.dnanexus.com/panx/projects.

References

Soriano, J.B. et al. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 8, 585–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30105-3 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Global National life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 388, 1459–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Trends and risk factors of mortality and disability adjusted life years for chronic respiratory diseases from 1990 to 2017: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Bmj 370, m3150, doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3150 (2020).

Byrne, C. D. & Targher, G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J. Hepatol. 62, 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.012 (2015).

EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetologia 59, 1121–1140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-3902-y (2016).

Zhao, Q. & Deng, Y. Comparison of mortality outcomes in individuals with MASLD and/or MAFLD. J. Hepatol. 80, e62–e64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.08.003 (2024).

Younossi, Z. M. et al. Are there outcome differences between NAFLD and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease? Hepatology 76, 1423–1437, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32499

Rinella, M. E. et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 79, 1542–1556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.06.003 (2023).

Mantovani, A. et al. MASLD, hepatic steatosis and fibrosis are associated with the prevalence of chronic kidney disease and retinopathy in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 50, 101497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2023.101497 (2024).

Lee, H. H. et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and risk of cardiovascular disease. Gut 73, 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2023-331003 (2024).

Visca, D., Pignatti, P., Spanevello, A., Lucini, E. & La Rocca, E. Relationship between diabetes and respiratory diseases-Clinical and therapeutic aspects. Pharmacol. Res. 137, 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2018.10.008 (2018).

Zeina, A. R. et al. Pulmonary embolism risk in hospitalized patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A case-control study. Med. (Baltim). 101, e31710. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000031710 (2022).

Roh, J. H. et al. A nationwide survey of the association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the incidence of asthma in Korean adults. PLoS One. 17, e0262715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262715 (2022).

Jia, Y. et al. Multi-system diseases and death trajectory of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: Findings from the UK biobank. BMC Med. 21, 398. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-03080-6 (2023).

Tilg, H., Adolph, T. E., Dudek, M. & Knolle, P. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: The interplay between metabolism, microbes and immunity. Nat. Metab. 3, 1596–1607. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-021-00501-9 (2021).

Young, R. P., Hopkins, R. J. & Marsland, B. The Gut-Liver-Lung axis. Modulation of the innate immune response and its possible role in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 54, 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2015-0250PS (2016).

Younossi, Z. M. et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 64, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28431 (2016).

Miller, M. J. et al. Progression to cirrhosis is similar among all ages in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, but liver-related events increase with age. Hepatol. Commun. 7 https://doi.org/10.1097/hc9.0000000000000148 (2023).

Pafili, K. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through the female lifespan: The role of sex hormones. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 45, 1609–1623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-022-01766-x (2022).

Nabi, O. et al. Lean individuals with NAFLD have more severe liver disease and poorer clinical outcomes (NASH-CO Study). Hepatology 78, 272–283. https://doi.org/10.1097/hep.0000000000000329 (2023).

Ha, J., Yim, S. Y. & Karagozian, R. Mortality and liver-Related events in lean versus Non-Lean nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 2496–2507e2495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2022.11.019 (2023).

Souza, M., Diaz, I. & Al-Sharif, L. Liver and cardiovascular outcomes in lean non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of about 1 million individuals. Hepatol. Int. 18, 1396–1415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-024-10716-z (2024).

Souza, M., Diaz, I., Barchetta, I. & Mantovani, A. Gastrointestinal cancers in lean individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver Int. 44, 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.15763 (2024).

Wongtrakul, W., Charatcharoenwitthaya, N. & Charatcharoenwitthaya, P. Lean non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the risk of all-cause mortality: an updated meta-analysis. Ann. Hepatol. 29, 101288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2024.101288 (2024).

Engin, A. B. Adipocyte-Macrophage Cross-Talk in obesity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 960, 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_14 (2017).

Zheng, M. et al. Genomic analysis of lean individuals with NAFLD identifies Monogenic disorders in a prospective cohort study. JHEP Rep. 5, 100692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2023.100692 (2023).

Chahal, D. et al. Distinctive clinical and genetic features of lean vs overweight fatty liver disease using the UK biobank. Hepatol. Int. 16, 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-022-10304-z (2022).

Jia, Y. et al. Association between metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and abdominal aortic aneurysm. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 34, 953–962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2023.11.004 (2024).

Anstee, Q. M. & Day, C. P. The genetics of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: spotlight on PNPLA3 and TM6SF2. Semin Liver Dis. 35, 270–290. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1562947 (2015).

Eslam, M., Valenti, L. & Romeo, S. Genetics and epigenetics of NAFLD and NASH: clinical impact. J. Hepatol. 68, 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.09.003 (2018).

Gjurašin, B., Jeličić, M., Kutleša, M. & Papić, N. The impact of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on severe Community-Acquired pneumonia outcomes. Life (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/life13010036 (2022).

Kotlyarov, S. & Bulgakov, A. Lipid metabolism disorders in the comorbid course of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cells 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10112978 (2021).

Hilliard, K. L. et al. The Lung-Liver axis: A requirement for maximal innate immunity and hepatoprotection during pneumonia. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 53, 378–390. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2014-0195OC (2015).

Shore, S. A. & Cho, Y. Obesity and asthma: Microbiome-metabolome interactions. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 54, 609–617. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2016-0052PS (2016).

Qian, H. et al. Autophagy in liver diseases: A review. Mol. Aspects Med. 82, 100973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2021.100973 (2021).

Fry, A. et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and Health-Related characteristics of UK biobank participants with those of the general population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 1026–1034. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx246 (2017).

Bedogni, G. et al. The fatty liver index: A simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 6 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230x-6-33 (2006).

Sberna, A. L. et al. European association for the study of the liver (EASL), European association for the study of diabetes (EASD) and European association for the study of obesity (EASO) clinical practice recommendations for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: evaluation of their application in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 35, 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13565 (2018).

Angulo, P. et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: A noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology 45, 846–854. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21496 (2007).

Mancina, R. M. et al. The MBOAT7-TMC4 variant rs641738 increases risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in individuals of European descent. Gastroenterology 150, 1219–1230e1216. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.032 (2016).

Caddeo, A., Spagnuolo, R. & Maurotti, S. MBOAT7 in liver and extrahepatic diseases. Liver Int. 43, 2351–2364. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.15706 (2023).

Speliotes, E. K. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variants associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease that have distinct effects on metabolic traits. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001324. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001324 (2011).

Santoro, N. et al. Variant in the glucokinase regulatory protein (GCKR) gene is associated with fatty liver in obese children and adolescents. Hepatology 55, 781–789. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24806 (2012).

Kozlitina, J. et al. Exome-wide association study identifies a TM6SF2 variant that confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Genet. 46, 352–356. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2901 (2014).

Kozlitina, J. Genetic risk factors and disease modifiers of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterol. Clin. North. Am. 49, 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2019.09.001 (2020).

Romeo, S. et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Genet. 40, 1461–1465. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.257 (2008).

Krawczyk, M., Liebe, R. & Lammert, F. Toward genetic prediction of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease trajectories: PNPLA3 and beyond. Gastroenterology 158, 1865–1880e1861. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.053 (2020).

Burns, E. M. et al. Systematic review of discharge coding accuracy. J. Public. Health (Oxf). 34, 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr054 (2012).

Horita, N. et al. Decline in mortality due to respiratory diseases in Japan during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Respirology 27, 175–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.14186 (2022).

Zhou, L. et al. Predictive value of lung function measures for cardiovascular risk: A large prospective cohort study. Thorax 79, 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax-2023-220703 (2024).

Collins, R. What makes UK biobank special? Lancet 379, 1173–1174. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60404-8 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the participants for their participation and contribution to this research in the UK Biobank study. This research was conducted using the UK Biobank resource under application number 112111.

Funding

This work was supported financially by grants from the 1.3.5 Project for Talent Excellence Development, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (No. ZYGD23035), the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (No. 2021YFS0023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. BL and YC designed the research. Dr. BL, YJ, and ZG analysed the data under the supervision of Dr. YC. Dr. BL and YJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Dr. BL, YJ, ZG, YL, YZ and YC reviewed the manuscript and provided critical scientific input. Dr. YC had main responsibility for the final content of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for the UK Biobank study was obtained from the NHS National Research Ethics Service (16/NW/0274). The experimental protocols were established according to the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants or their guardians. All methods were carried out in accordance with guidelines and regulations developed by the UK Biobank. The use of the data was approved by the Human Ethical Committee of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University (2023 − 1829).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Jia, Y., Gu, Z. et al. Metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease is associated with an increased risk of multiple respiratory system diseases. Sci Rep 15, 15937 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96710-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96710-3