Abstract

The challenge of harnessing entanglement during the non-equilibrium dynamics of open quantum systems, especially at high temperatures, is highly prominent within recent scientific researches. Due to the ongoing trend of miniaturization of quantum devices that exploit quantum correlations, proposing novel schemes to overcome this challenge is itself a crucial task within current quantum technological research. We contribute to this research by proposing a new scheme to control entanglement dynamics of a non-equilibrium two-qubit Heisenberg XXZ spin chain model in an external magnetic field. The design of the scheme is based on a coupling asymmetry in the model induced by the asymmetrical connection of qubits to two independent thermal reservoirs. While in the absence of the coupling asymmetry, non-equilibrium effects generally suppress the dynamical generation of thermal entanglement, making entanglement production impossible at high mean temperatures of reservoirs, it is shown that this asymmetry in the coupling potentially enables us to generate a maximal non-equilibrium entanglement even in the high mean temperature regime. We show that the coupling asymmetry can also lead to a complete protection of the maximum initial entanglement between the qubits at high mean temperatures of the reservoirs thanks to the non-equilibrium conditions. Depending on the initial state of the two qubits, this can be achieved either by accessing a coherence-free subspace or by fully reviving the initial qubit-qubit entanglement. Furthermore, we investigate the quantum heat transport of the chain, and find that by turning on the asymmetry in the qubit-reservoir coupling, although the chain loses its initial thermal rectification property over time, it regains this property and maintain it until the non-equilibrium steady state is reached. Our results show that, at higher temperature gradients, the chain leverages the steady-state entanglement to completely block the heat released from the hot reservoir. Our findings can be significant for heat management in quantum computing devices such as solid-state thermal circuits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum entanglement or as Einstein called it, “spooky action at a distance”, is a fundamental quantum mechanical phenomenon that occurs when two or more individual particles enter into a temporary (in)direct interaction. As a consequence of entanglement, two entangled particles effectively abandon their individuality and behave as a single entity, even when spatially separated1. The emerging quantum technologies, such as quantum teleportation2, quantum telecloning3, quantum dense coding4, quantum cryptography5 and quantum computing6 benefit significantly from the manipulation and control of entanglement. In practice, however, quantum systems are open to the surrounding environment, and decoherence caused by the system-environment interaction generally destroys entanglement in times much shorter than those required for implementing quantum information processes7,8,9. Nevertheless, decoherence can also be useful, and may indeed be utilized to generate quantum entanglement under suitable conditions10. Consequently, understanding the dynamical behavior of entanglement in the presence of decoherence is crucial for generating and harnessing quantum features against the environmental noises (see11 and references therein). For this end, several studies have been carried out to investigate the dynamical behaviors of the entanglement among the quantum systems subjected to various environmental decoherence effect, and building on these studies several methods have been proposed in recent years to avoid decoherence12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37.

On the other hand, over the last few decades, entanglement dynamics of the Heisenberg spin chains have garnered significant interest. This is because the Heisenberg spin systems describe the novel physics of localized spins in the magnetic systems. Additionally, they play a crucial role in modeling many of new miniaturized systems such as quantum heat engines38, quantum batteries40,41,42, quantum gates43 and quantum transistors39, and are also current-front runners in the practical realization of solid-state quantum computation schemes. For example, the Heisenberg chains have been used to construct quantum computers based on, quantum nuclear spins44,45, quantum dots46,47, and quantum optical lattices48.

During the last decade, there has been a growing interest in the study of the generation and protection of entanglement induced by thermal interactions between the quantum systems and their environments. Thermally induced entanglement is important in many situations, especially in the solid-state systems. Therefore, the relationship between quantum entanglement and thermal observables needs to be elucidated. The notion of thermal entanglement was proposed by Nielsen in a spin chain system at thermal equilibrium49, since then, thermal entanglement has been studied extensively in a variety of physical systems50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65 over the past two decades. However, the assumption that real systems are in equilibrium has been questioned, bringing quantum correlations under non-equilibrium conditions to the center of the debate. The simplest configuration that allows for the investigation of quantum correlations under non-equilibrium conditions is likely a two-spin Heisenberg system, where each spin is coupled to a separate reservoir66. Due to the temperature difference of the thermal reservoirs, a typical characteristic of non-equilibrium open quantum systems is the quantum heat current that flows from the hot reservoir to the cold one through the open system67,68. This important characteristic has been widely used to design a series of thermal devices such as thermal diodes28,69, quantum thermal batteries70, thermal transistors71, thermal memory72. In one of the early studies on the non-equilibrium thermal entanglement, Quiroga and et al.73 evaluated the concurrence of a two-qubit Heisenberg XXX spin model and showed that the enhancement of the concurrence due to the temperature gradient is possible. Sinaysky et al.74 studied analytical solution and non-equilibrium dynamics of a two-qubit Heisenberg XX model, by analyzing the effect of system parameters on the thermal entanglement between the qubits in the steady state to which the system relaxes over long times. The authors of75 extended the study of non-equilibrium steady-state entanglement to a three-qubit XX model with the help of effective Hamiltonian approach. Ref.76 explored non-equilibrium entanglement dynamics of a two-qubit Heisenberg XY system in the presence of an inhomogeneous magnetic field and spin-orbit interaction. Subsequently, Ref.77, discussed non-equilibrium steady-state entanglement and coherence of two coupled qubits in the general non-equilibrium setting for both boson and fermion reservoirs. Moreover, dynamical behaviors of entanglement and quantum discord in a two-qubit Heisenberg XYZ model interacting with two independent thermal reservoir has been investigated in78.

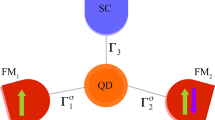

All of the previous studies on the non-equilibrium thermal entanglement between two couples qubits have been limited to simplified cases, and some of the possible couplings between the qubits and baths have been neglected. An interesting scenario arises when one considers a two-qubit Heisenberg XXZ model in an external magnetic field asymmetrically coupled to two independent thermal baths in which one qubit coupled to both cold and hot reservoirs, while the other qubit is just connected to the cold reservoir (see Fig. 1). The configuration asymmetry induced by the asymmetric couplings of a Heisenberg XXZ spin-chain quantum battery to two thermal baths has been shown to enhances energy stored in the non-equilibrium steady state of that battery42. This asymmetry also brings the passive steady state of a non-equilibrium Heisenberg XXZ spin chain to an active state from which a positive work can be extracted through unitary cyclic processes. In this work, we aim to exploit the additional connection of the hot bath to one of the qubits and harness dynamical behavior of non-equilibrium entanglement as well as heat current among the qubits of same model. We also investigate in detail the non-equilibrium effects especially the influence of temperature gradient on the dynamics of entanglement, and carefully analyse the possibility of generation and preservation of maximal entanglement during the dynamical evolution through the non-equilibrium condition.

The paper is organized as follows. In “The model and its analytical solutions”, we introduce the two-qubit Heisenberg XXZ model in an external magnetic field and drive its Markovian dynamics in both the symmetric and asymmetric coupling configurations. In “Results and discussion”, by choosing different initial two-qubit states, we examine the influence of the chain anisotropy, external magnetic field and temperature gradient of reservoirs on the non-equilibrium entanglement and heat current between the qubits, and lay out the different results in generating and harnessing the non-equilibrium entanglement and heat current in the symmetric and asymmetric coupling configurations. Finally, in “Outlook and summary” we draw some conclusions from the present study and give concluding remarks on possible physical realizations of our non-equilibrium model.

The model and its analytical solutions

The model under consideration consists of a two-qubit antiferromagnetic XXZ Heisenberg spin system subjected to a static uniform magnetic field and interacting with two independent thermal baths. Figure 1 illustrates a schematic diagram of the interaction between the spin chain system and thermal reservoirs. As can be seen, a coupling switch is used to provide the interaction of qubis and baths in two symmetrical or asymmetrical configurations. In the symmetrical coupling configuration where the switch is off, the qubit 1 is coupled to the left bath and the qubit 2 to the right bath. In the asymmetrical coupling configuration, the switch is flipped on, and an extra connection between the qubit 2 and left bath will be established. At this time, qubit 2 interacts with both baths, whereas the qubit 1 is coupled just to the left bath.

The schematic diagram of the two-qubit Heisenberg XXZ model with two coupled qubits 1 and 2 interacting with a non-equilibrium environment consisting of left and right reservoirs. The key \(\varepsilon\) is used to switch on/off the coupling between the qubit 2 and left reservoir, allowing us to control chain-reservoir coupling asymmetry.

The Hamiltonian describing the above model reads

where \(H_S\) is the free Hamiltonian of the two-qubit spin chain described by a two-qubit Heisenberg XXZ system in the presence of an uniform external field \(B_0\)79,80

\(\sigma _x^{(i)}\), \(\sigma _{y}^{(i)}\) and \(\sigma _{z}^{(i)}\) (\(i=1,2\)) are spin 1/2 operators for the ith spin and B is a magnetic field in the z direction. \(J>0\) indicates interqubit coupling and \((0\le \Delta \le J)\) denotes the chain anisotropy in the z direction. Remarkably, for the particular values \(\Delta =0\) and \(\Delta =J\), the Hamiltonian (2) corresponds to the XX81 and XXX82 spin chains, respectively. In the two-qubit bare basis \(\{|1,1\rangle ,|1,0\rangle ,|0,1\rangle ,|0,0\rangle \}\), the eigenenergies and corresponding eigenbasis of \(H_S\) are

The Hamiltonians for the left and right baths are given by (\(\hbar =1\) and \(k_B=1\) in the following)

where \(a_{j_L}\) \((a^{\dagger }_{j_L})\) and \(a_{j_R}\) \((a^{\dagger }_{j_R})\) are the annihilation (creation) operators associated with the \(j-\)th bosonic mode of the left and right bath, respectively. For simplicity, we only consider the dissipative interaction between the system and the environment, excluding pure dephasing type environmental noise. Therefore, the interaction between the qubits and the thermal baths can be written as

where \(\lambda _{j_L}\) (\(\lambda _{j_R}\)) is the dissipative interaction strength between the qubit and the left (right) bath. In addition, \(\varepsilon\) is a switching parameter which gets 0 or 1. Precisely, \(\varepsilon =0\) switches off the connection between qubit 2 and left bath. In this situation we have a symmetric coupling configuration. Conversely, \(\varepsilon =1\) switches on the connection between qubit 2 and the left bath, inducing an asymmetry in the qubit-bath coupling.

We assume that the qubit-bath interaction strength is in the weak coupling regime. Therefore, using the theory of the open quantum systems with the Born-Markov and rotating wave approximations, dynamics of the reduced density matrix of two-qubit Heisenberg XXZ system can be described by the following Lindblad form master equation83

where \(H_{Ls}\) and \(\mathfrak {D}_{L(R)}(\rho )\) are the Lamb-shift correction to the system Hamiltonian and dissipator associated with the left (right) bath, respectively. The dissipator takes the form as

where, \(\mathcal {J}_{\nu }(\omega )=\pi \sum _{j}|\lambda _j^{\nu }|^2\delta (\omega -\omega ^{(\nu )}_j)\) is the spectral density of the bath \(\mathcal {R}_{\nu }\), \(n_{\nu }(\omega )=\left[ e^{\frac{\omega }{T_{\nu }}}-1\right] ^{-1}\) denotes the average particle number on frequency \(\omega\) in that bath, and \(A_{\nu }(\omega )\) and \(A_{\nu }^{\dag }(\omega )\) are the transition operators satisfying \(A_{\nu }(\omega )=A_{\nu }^{\dagger }(-\omega )\) and the commutation relation \([H_B,A_{\nu }(\omega )]=-\omega A_{\nu }(\omega )\). The transition operators are constructed as follows

for all positive eigenfrequencies \(\omega =\omega _{ij}=E_i- E_j>0\), corresponding to the transitions \(|\Phi _i\rangle \rightarrow |\Phi _j\rangle\).

In addition, the Lamb-shift Hamiltonian in Eq. (6) reads

where \(S_{\nu }(\omega )\) is imaginary parts of the Fourier transform of the reservoir correlation function \(\langle \mathcal {B}_{\nu }(t) \mathcal {B}_{\nu }(0) \rangle\), takes the following form

with \(\mathbb {P}\) denoting the Cauchy principal value. In the following, we are interested in the Ohmic dissipation, \(\mathcal {J}_{\nu }(\omega )=\kappa \omega\), where \(\kappa\) is a dimensionless constant that quantifies dissipation strength. It should be noted that, in order to guarantee the validity of the Markovian approximation, \(\kappa\) needs to satisfy the condition \(\kappa \ll \{B_0, J, \Delta \}\). Using the Eqs. (8a) and (8b), we can derive an explicit expression for the dissipator \(\mathfrak {D}_{\nu }(\rho )\),

where \(\tau _{ij}=|\Phi _i\rangle \langle \Phi _j|\), \(L_{X}=X\rho X^{\dagger }-\frac{1}{2}\{\rho ,X^{\dagger }X\}\) and

where \(\gamma _{ij}^{(\nu ,e)}\) (\(\gamma _{ij}^{(\nu ,a)}\)) is emission (absorption) rate from \(|\Phi _i\rangle\) to \(|\Phi _j\rangle\) (\(|\Phi _j\rangle\) to \(|\Phi _i\rangle\)), thanks to the interaction of the spin chain with the bath \(\nu\). From the above set of equations, the emission and absorption rates \(\gamma _{31}^{(L,e)}\), \(\gamma _{31}^{(L,a)}\), \(\gamma _{23}^{(L,e)}\) and \(\gamma _{23}^{(L,a)}\) will be zero when the coupling switch is flipped on (\(\varepsilon =1\)). This means that the energy transitions \(|\Phi _1\rangle \leftrightarrow |\Phi _3\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _2\rangle \leftrightarrow |\Phi _3\rangle\) induced by the hot (left) bath are impossible. All allowed energy transitions induced by the chain-bath interaction are depicted in Fig. 2, at which a four-level qudit will be populated due to the interaction with both the left and right baths. Meanwhile, to get the effect of the Lamb shift, we define

then the Lamb-shift Hamiltonian can be rewritten as

where \(\Delta _k\) in the symmetric and asymmetric coupling configurations are given respectively as

According to Eq. (14), the Lamb-shift Hamiltonian \(H_{Ls}\) commutes with \(H_S\), indicating that it represents an effective shift in the eigenenergies of the system. Due to the fact that \(H_{Ls}\) is of the second order in terms of the interaction Hamiltonian \(H_{S-B_{L(R)}}\), Lamb shift appears here as a second-order correction to the dynamics. Although in some studies the Lamb-shift corrections to the eigenenergies are ignored due to their smallness, a careful analysis of the Lamb-shift corrections are still in order.

To solve the master equation (6), it is often useful to represent it in the energy basis \(|\Phi _i\rangle |_{i=1}^4\). In the energy basis the master equation is reduced to two sets of differential equations: one set is differential equations for the population (diagonal) elements and the other is for the coherence (non-diagonal) elements. The differential equations for the coherence elements are not coupled and have the simple form \(\dot{\rho }_{ij}(t)= -M_{ij}\rho _{ij}(t)\). The time dependence of these elements can be obtained easily as \(\rho _{ij}(t)=\rho _{ij}(0)e^{-M_{ij}t}\), where \(M_{ij}\) are given by

and \(M_{21}=M^{*}_{12}\), \(M_{31}=M^{*}_{13}\), \(M_{32}=M^{*}_{23}\), \(M_{41}=M^{*}_{14}\), \(M_{42}=M^{*}_{24}\) and \(M_{43}=M^{*}_{34}\). In the above equations \(*\) denotes complex conjugation. However differential equations for the populations can be rewritten with the form

where \(\vec {\rho }(t)\) is a single vector given by \(\vec {\rho }(t)=(\rho _{11},\rho _{22},\rho _{33},1-\rho _{11}-\rho _{22}-\rho _{33})^T\), and N is a \(4\times 4\) coefficient matrix with the following nonzero components

The formal solution of Eq. (17) is given by

where the matrix exponentials \(\exp [\xi t]\) can be computed readily using the diagonal representation of the coefficient matrix N, as follows

where, \(\lambda _i\) are eigenvalues of the coefficient matrix N, and S is the unitary matrix which diagonalizes N, satisfying \(S^{-1}\,N\,S=\textrm{diag} (\lambda _1,...,\lambda _{4})\). After straightforward but tedious algebras, we find the dynamical solution for the population components \(\rho _{ii}(t)\). However, the resulting solutions are quite lengthy, so we omit them here. From Eqs. (16)–(20), it is evident that the Lamb-shift term does not influence the evolution of the population terms. However, the evolution of the coherence terms depends on the Lamb-shift Hamiltonian.

Now we have all the expressions in hand required to analyze the dynamics of quantum features of the chain. In the next section, we will explore the non-equilibrium effects on the dynamical behavior of entanglement and heat current between the qubits by considering various initial two-qubit states in both the symmetric \((\varepsilon =0)\) and asymmetric \((\varepsilon =1)\) qubit-bath coupling configurations. More importantly, we will investigate the possibility of protecting initial entanglement as well as dynamically generating maximal qubit-qubit entanglement in the asymmetric coupling configuration and find the proper conditions that make the chain a thermal diode. To quantify qubit-qubit entanglement, we use the Wootters concurrence measure84 defined as follows:

with \(\mu _i\)’s are the eigenvalues in decreasing order of \(\tilde{\rho }(t)\) where \(\tilde{\rho }(t)=\rho (t)\left( \sigma _y^1\otimes \sigma _y^2\right) \rho ^{*}(t)\left( \sigma _y^1\otimes \sigma _y^2\right)\) denotes the spin flip density matrix with \(\rho ^{*}(t)\) and \(\sigma _y^i\) being the complex conjugate of \(\rho (t)\) and the y-component of Pauli operator for the i-th qubit, respectively. The concurrence C ranges from 0 for a separable (unentangled state) to 1 for a maximally entangled state.

Furthermore, the heat current from the baths into the system can be unambiguously defined as the time variation of the internal energy of the baths being of the form85,86

where \(Q_{\nu }(t)=\textrm{Tr}\big \{\mathfrak {D}_{\nu }[\rho (t)]H_S\big \}\), (\(\nu =L,R\)) represents the heat current from the reservoir \(\mathcal {R}_{\nu }\) into the system. A positive heat current means that heat flows from the reservoir to the system, while a negative value indicates heat absorption by the reservoir from the system. Therefore, a change of sign of the heat current can be used as a witness for a crossover between heat absorption and heat release or vice versa. By substitution Eq. (11) to (22), the heat current from the bath \(\mathcal {R}_{\nu }\) reads

where \(\Gamma _{ij}^{\nu }(t)=\gamma _{ij}^{(\nu ,e)}\rho _{ii}(t)-\gamma _{ij}^{(\nu ,a)}\rho _{jj}(t)\) is net decay rate from the state \(|\Phi _i \rangle\) to \(|\Phi _j \rangle\). Notice that in general \(Q_{L}(t)\ne -Q_{R}(t)\), but once the steady state is reached, the total heat current flowing through the qubits must be zero, i.e., \(Q_{L}(t=\infty )+Q_{R}(t=\infty )=0\).

The heat may flow asymmetrically if the bath temperature is interchanged. In this situation, the two-qubit chain works as a heat rectifier87. Such asymmetric heat current is conventionally quantified by the rectification coefficient88,89

where \(Q_L^{r}\) is the heat current when the temperatures of the baths are interchanged. Note that \(0\le \Re \le 2\). Evidently, \(\Re\) is zero for the case where heat flows symmetrically through the qubits: \(Q_L^{r}=-Q_L\) and gets extreme 2 when the heat flows through the qubits independent of the sign of the temperature gradient: \(Q_L^{r}=Q_L\). Also, \(\Re =1\) is achieved when the qubits completely block the heat flow in one direction and thus the chain behaves as a perfect thermal diode.

Results and discussion

We now present numerical results for the dynamics of entanglement and heat current between the qubits for various initial two-qubit states in both the symmetric qubit-bath \((\varepsilon =0)\) and asymmetric qubit-bath \((\varepsilon =1)\) configurations. More importantly, we reveal the role of non-equilibrium effects on generation and protection of entanglement, in both the \(\varepsilon =0\) and \(\varepsilon =1\) cases, by investigating the effect of the temperature gradient of baths \(\Delta T=T_L-T_R\) on the dynamics of entanglement. Furthermore, we investigate heat current and the intriguing phenomenon of thermal rectification with emphasis on the role of asymmetry in the system-bath couplings.

Entanglement generation

In Fig. 3, we display dynamically generation of entanglement for the separable two-qubit initial state \(|\Phi _1\rangle =|00\rangle\), considering various values of the

Dynamics of concurrence as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(T_M\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B_0=0.6 J\) and \(\Delta =0.5 J\). The initial state is \(|\Phi _1\rangle =|00\rangle\). The plots correspond to the symmetric coupling configuration, i.e., \(\varepsilon =0\) (panels (a) and (b)) and asymmetric coupling configuration, i.e., \(\varepsilon =1\) (panels (c) and (d)). Panels (a) and (c), refer to \(T_M=0.5J\), while panels (b) and (d) refer to \(T_M=2J\).

temperature gradient \(\Delta T=T_L-T_R\). Here, we plot the concurrence as a function of Jt with the system parameters \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(\Delta =0.5J\) and \(B_0=0.6J\). In panels (a) and (b), the coupling switch is off \((\varepsilon =0)\) and thus the qubits interact with baths in the symmetrical coupling configuration, while in panels (c) and (d) the coupling switch is on \((\varepsilon =1)\) and thus the qubits interact with baths in the asymmetrical coupling configuration. Additionally, in panels (a) and (c) the mean temperature of the baths \(T_M=\frac{T_L+T_R}{2}\) is assumed to be low (e.g., \(T_M=0.5J\)), while in panels (b) and (d) \(T_M\) it is assumed to be sufficiently high (e.g., \(T_M=2J\)). We note that for initial state \(|\Phi _1\rangle =|00\rangle\), the coherence elements of matrix density \(\rho _{ij}(t)\) are zero, and therefore the Lamb shift does not affect the dynamical generation of entanglement between the qubits. Figure 3 shows that, at the low mean temperatures, the qubits become dynamically entangled in both the symmetric and asymmetric coupling configurations. Nevertheless, dynamically generation of qubit-qubit entanglement is possible only in the asymmetric coupling scenario when the mean temperature of baths is high enough (e.g., \(T_M=2J\) in the figures). Interestingly, in the asymmetric scenario, if entanglement is generated between the qubits, this occurs after a finite time has elapsed, whereas in the asymmetric scenario the qubits may become entangled at low mean temperature as soon as the dynamics begins.

To understand why the dynamical generation of qubit-qubit entanglement is possible in the asymmetric coupling configuration even when the mean temperature of baths is high enough, we look at the dynamics of the eigenstates populations \(\rho _{ii}=\langle \Phi _i|\rho |\Phi _i\rangle\) at high mean temperatures of the reservoirs. In Fig. 4 we plot \(\rho _{ii}\) as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for the initial state \(|\Phi _1\rangle\) corresponding to the panel (d) of Fig. 3.

Dynamics of the eigenstates populations as a functions of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B_0=0.6 J\), \(\Delta =0.5 J\) and \(T_M=2J\). The plots correspond to the asymmetric coupling configuration (\(\varepsilon =1\)), and the initial state is \(|\Phi _1\rangle =|00\rangle\).

As one can see, due to the direct and indirect transitions from \(|\Phi _1\rangle\) to \(|\Phi _2\rangle\), \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _4\rangle\), the eigenstate populations \(\rho _{11}\) (\(\rho _{jj}\), \((j=2,3,4)\)) decreases (increase) with time and then approaches some steady-state values depending on the value of \(\Delta T\). Also, at equilibrium condition at which the steady state of the system obeys the Gibbs distribution, the steady-state populations satisfy the ordering \(\rho _{22}<\rho _{44}<\rho _{11}<\rho _{33}\) as expected because the eigenstates satisfy the ordering \(E_3<E_1<E_4<E_2\) for \(B_0\le |J+\Delta |\). When the positive temperature gradient increases, the steady-state populations of \(|\Phi _1\rangle\), \(|\Phi _2\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) decreases, leading to an increase in the steady-state population of the ground state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\). Specially, at the higher temperature gradient \(\Delta T=2T_M\), once the system reaches the steady state, it populates exactly at the Bell state \(\Phi _3\) which is sufficient for the two-qubit steady-state concurrence to reach its maximum value. The physical reason behind the dynamical behavior of the populations at higher temperature gradient \(\Delta T=2T_M\) is quite clear: As we saw in the previous section, the transitions \(|\Phi _3\rangle \leftrightarrow |\Phi _1\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _3\rangle \leftrightarrow |\Phi _2\rangle\), induced by the interaction of the system with the left bath are never allowed in the asymmetric coupling configuration. On the other hand, from Eq. (12a), fixing \(T_L\) and

Dynamics of concurrence as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt and magnetic field \(B_0/J\) for the initial state \(|\Phi _1\rangle =|00\rangle\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(T_M=2J\), \(\Delta T=2T_M\) and \(\Delta =0.5 J\). The panels (a) and (b) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting, i.e., \(\varepsilon =0\) and asymmetric coupling setting, i.e., \(\varepsilon =1\), respectively.

taking the limit \(T_R\simeq 0\) (the high temperature gradient limit), we have \(\gamma _{13}^{(R,a)}=\gamma _{23}^{(R,a)}=0\), \(\gamma _{13}^{(R,e)}=\frac{\kappa (J+\Delta -B_0)}{2}\) and \(\gamma _{23}^{(R,e)}=\frac{\kappa (J+\Delta +B_0)}{2}\) for \(B_0\le |J+\Delta |\). This means that at high temperature gradients and for \(B_0\le |J+\Delta |\), the transitions from the entangled two-qubit Bell state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) into the separable basis \(|\Phi _1\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _2\rangle\) induced by the interaction of qubits with the right bath are forbidden, but the reverse transitions occur. Therefore, in the asymmetric coupling configuration, the population of the Bell state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) always increases at \(\Delta T=2T_M\) and for \(B_0\le J+\Delta\), leading to a population trapping phenomenon90 in this temperature gradient limi.

In Fig. 5 we investigate the effect of magnetic field \(B_0\) on the dynamically generation of entanglement between the qubits \(|\Phi _1\rangle =|0,0\rangle\). We here plot the concurrence as a function of \(\tau =J t\) and \(B_0/J\) for the mean temperature \(T_M=2J\) by adjusting the system parameters as \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(\Delta =0.5J\), and \(\Delta T=2T_M\). Panel (a) depicts the dynamics of concurrence in the symmetric configuration, while panel (b) corresponds to the asymmetric coupling configuration. It is evident that the generation of entanglement is not affected by the magnetic field when the coupling switch is flipped off (\(\varepsilon =0\)). However, when the coupling switch is on (\(\varepsilon =1\)), the generated entanglement at the long times decreases with the magnetic field, as shown in panel (b).

Entanglement protection

In Fig. 6, we display the dynamics of entanglement for the initial maximally entangled state \(|\Phi _3\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle -|1,0\rangle \right]\), corresponding to the panels of Fig. 3. We note that for the chosen initial state, the coherence elements of matrix density \(\rho _{ij}(t)\) become zero, and therefore the Lamb shift does not affect the dynamics of entanglement.

Dynamics of concurrence as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(T_M\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B_0=0.6J\) and \(\Delta =0.5 J\). The initial state is \(|\Phi _3\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle -|1,0\rangle \right]\). The plots correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\) (panels (a) and (b)) and asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\) (panels (c) and (d)). Panels (a) and (c), refer to \(T_M=0.5J\), while panels (b) and (d) refer to \(T_M=2J\).

In the symmetric scenario, as shown in Fig. 6a,b, concurrence starts from its maximum value, decays over time and finally reaches a nonzero steady-state value for the chosen temperature gradient \(\Delta T\). We find that increasing the temperature gradient speeds up the decay rate of concurrence in both the low and high temperature regimes. This implies that the non-equilibrium feature of the environments plays a destructive role in protecting the initial entanglement of qubits in the symmetric coupling configuration. In the asymmetric coupling, however, increasing the temperature gradient, albeit at the positive bias, markedly slows down the decay rates of concurrence as illustrated in Fig. 6c,d. In particular, one could stop entanglement decay even at a high base temperature of the baths, provided the temperature gradient is increased to \(\Delta T=2T_M\). These results indicate that the temperature gradient between the reservoirs plays a constructive role in protecting the initial entanglement of qubits in the asymmetric coupling configuration.

To understand why in panels (c) and (d) the concurrence does not decay below one under the extreme condition (i.e., in the higher positive temperature gradient limit), we turn to previous subsection, where we proved that the transitions from the entangled two-qubit Bell state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) into other eigenstates are forbidden in the higher positive temperature gradient limit \(\Delta T=2T_M\) for \(B_0\le J+\Delta\). Therefore, in Fig. 6 entanglement preservation can be the result of confining the dynamics to the decoherence-free subspace \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) of the system’s Hilbert space. Note that a decoherence-free subspace is a subspace of a quantum system’s Hilbert space that is invariant to non-unitary dynamics. The states belonging to this subspace are called sub-radiant states.

Dynamics of concurrence as a functions of the dimensionless quantity Jt and magnetic field \(B_0/J\) for the initial state \(|\Phi _3\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle -|1,0\rangle \right]\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(T_M=2J\) and \(\Delta =0.5 J\). The panels (a) and (b) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\) and asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\), respectively.

Furthermore, in Fig. 7 we have explored the effect of the magnetic field on the preservation of the initial entanglement contained in \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) when the base temperature of reservoirs is relatively high (e.g., for \(T_M=2J\)). The panels (a) and (b) display concurrence as a function of Jt and \(B_0/J\) in the symmetric and asymmetric coupling configurations, respectively. Here the system parameters are chosen as \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(\Delta =0.5J\), and \(\Delta T=2T_M\). According to panel (a), when the coupling switch is flipped off (\(\varepsilon =0\)), the dynamics of concurrence is almost insensitive to changes in the magnetic field strength. However, when the switch is flipped on (\(\varepsilon =1\)), the dynamics of concurrence can be controlled by the magnetic field, as shown in panels (b). We observe that the decay of concurrence is slowed down by decreasing the strength of the magnetic field, thereby completely protecting the initial maximal entanglement of the qubits by adjusting the strength of the magnetic field within interval [0, 1.5J].

Entanglement death and rebirth

Finally, we explore the dynamics of entanglement for the initial maximally entangled state \(|\Phi _4\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle +|1,0\rangle \right]\). Here the Lamb shift does not affect the dynamics of entanglement because of the chosen initial state.

Dynamics of concurrence as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(T_M\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B_0=0.6J\) and \(\Delta =0.5 J\). The initial state is \(|\Phi _4\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle +|1,0\rangle \right]\). The plots are related to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\) (panels (a) and (b)) and asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\) (panels (c) and (d)). Panels (a), (c), refer to \(T_M=0.5J\), while panels (b), (d), refer to \(T_M=2J\).

In Fig. 8, we depict concurrence as a function of Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\), corresponding to the panels of Fig. 3. The results indicates that concurrence starts from its maximum value, dissipates to zero over the time (entanglement death), but rebirth after a period of time and finally reaches a steady-state value (entanglement rebirth). Comparing panels (a) with (b) and also (c) with (d) reveals that increasing the mean temperature \(T_M\) speeds up the death rate of entanglement in both symmetric and asymmetric coupling configurations. Notably, in the symmetric coupling configuration, high mean bath temperatures prevent the revival of dead entanglement. While, when entanglement death is followed by revival in the symmetric coupling configuration at low mean temperature, it occurs relatively quickly compared to the asymmetric coupling configuration.

Furthermore, similar to the dynamics of concurrence for the initial states \(|\Phi _1\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _3\rangle\), the non-equilibrium effect exhibits contrasting roles in the symmetric and asymmetric coupling configurations. In the symmetric coupling configuration, increasing temperature gradient suppresses the entanglement rebirth, as illustrated in panels (a) and (b), while in the asymmetric coupling configuration, the amount of revived entanglement enhances with the temperature gradient and becomes comparable to its initial maximum (see panels (c) and (d)). In the asymmetric configuration, a complete revival is achieved by adjusting the temperature gradient to \(\Delta T= 2T_M\). These findings imply that the non-equilibrium feature of the environments plays a destructive (constructive) role in reviving the initial entanglement of qubits in the symmetric (asymmetric) coupling configuration.

Dynamics of the eigenstates populations as a functions of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B_0=0.6 J\), \(\Delta =0.5 J\) and \(T_M=2J\). The plots correspond to the asymmetric coupling configuration (\(\varepsilon =1\)), and the initial state is \(|\Phi _4\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle +|1,0\rangle \right]\).

In order to gain a physical understanding of the behavior of concurrence in the asymmetric configuration, it is useful to explore dynamical behavior of the eigenstate populations for the initial state \(|\Phi _4\rangle\). In Fig. 9 we plot the eigenstate populations \(\rho _{ii}\) as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for the initial state \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) corresponding to panel (d) of Fig. 8. This figure shows that, as soon as the evolution starts, the direct transitions from \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) to \(|\Phi _1\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _2\rangle\) (please see Fig. 2) lead to a rapid increase in the population of the eigenstates \(|\Phi _1\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _2\rangle\), while the indirect transition between \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) leads to a slow increase in the population of \(|\Phi _3\rangle\). In turn, this suggests sudden death of entanglement at the beginning of the evolution. As can be seen, the population of \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) increases monotonously with time to reach its steady-state value. For \(\Delta T\le 0\), this increase is too small for the combined weight of the populations on the eigenstates to be able revive the dead entanglement. However, as illustrated in panels (c) and (d), for \(\Delta T>0\), the population of \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) increases over time and exceeds 0.5 which is sufficient to revive the dead qubit-qubit entanglement after a period of time. At higher temperature gradient \(\Delta T=2T_M\), the steady-state population of \(|\Phi _1\rangle\), \(|\Phi _2\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) becomes zero and thus the system populates exactly at the Bell state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\). This explains why in Fig. 8 the lines for \(\Delta T=2T_M\) reach one at steady state, while those for other values of \(\Delta T\) do not.

In Fig. 10, we examine the effect of magnetic field on the entanglement dynamics of the initial state \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) when the base temperature of baths is relatively high. In this figure, the panels (a) ((b)) corresponds to dynamics of concurrence in the symmetric (asymmetric) configuration. From panel (a), it is evident that, similar to the entanglement dynamics of the initial states \(|\Phi _1\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _3\rangle\), the entanglement of the initial state \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) is not affected by the magnetic field when the coupling switch is off.

Dynamics of concurrence as a functions of the dimensionless quantity Jt and magnetic field \(B_0/J\) for the initial state \(|\Phi _4\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle +|1,0\rangle \right]\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(T_M=2J\) and \(\Delta =0.5 J\). Panel (a) and (b) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\) and asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\), respectively.

However, our results in panel (b) show that when the coupling switch is on, magnetic field affects the entanglement dynamics of \(|\Phi _4\rangle\). As shown in this panel, with the increase of \(B_0/J\) the revival time is shifted to longer times.

Heat current and thermal rectification: without the Lamb shift contribution

In this section we investigate the transient energy (heat) exchange between the qubits and reservoirs as well as thermal rectification, for the separable two-qubit initial states \(|\Phi _1\rangle =|00\rangle\) as well as the entangled two-qubit \(|\Phi _3\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle -|1,0\rangle \right]\) and \(|\Phi _4\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle +|1,0\rangle \right]\). Here, for simplicity, but without loss of generality, we ignore the Lamb shift contribution to the Lindblad equation (6).

In Fig. 11, we plot \(Q_L\) and \(Q_R\) as a function of Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\) in both symmetric and asymmetric coupling configurations. The system parameters are the same as in Fig. 3.

Dynamics of heat current \(Q_L\) and \(Q_R\) as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B_0=0.6J\), \(\Delta =0.5 J\) and \(T_M=2J\). Here, the initial state of qubits is \(|\Phi _1\rangle =|00\rangle\) and the Lamb-shift term is not included. Panels (a) and (c) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\), while (b) and (d) correspond to asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\) setting.

Panels (a) and (c) represent dynamics of quantum heat current in the symmetric coupling configuration, while (b) and (d) display dynamics of quantum heat current in the asymmetric coupling configuration. As expected, in both the symmetric and asymmetric coupling settings, the absolute value of the heat current increases with the temperature gradient. In the symmetric coupling scenario, as shown in the panels (a) and (c), heat initially flows from the qubits into the hot and cold bath. However, after some time, the direction of heat transfer from the qubits to the hot bath is reversed and the qubits start to absorb heat from the hot bath and reject it to the cold one. At this stage, the heat current absorbed (released) from (to) the hot (cold) bath increases with time to saturate at the steady-state values. In the symmetric coupling setting, the quantum heat currents \(Q_L\) and \(Q_R\) are equal regardless of the temperature gradient’s sign, as expected. However, the heat current seems to saturate faster (slower) by increasing \(\Delta T\) for the positive (negative) temperature gradient. In contrast, the dynamics of \(Q_L\) and \(Q_R\) undergo significant changes when coupling asymmetry is turned on, as depicted in panels (b) and (d).

Dynamics of the thermal rectification factor \(\Re\) as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B_0=0.6J\), \(\Delta =0.5 J\) and \(T_M=2J\). Here, the initial state of qubits is \(|\Phi _1\rangle =|00\rangle\) and the Lamb-shift term is not included. Panels (a) and (b) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\) and asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\), respectively.

Here, \(Q_L\) consistently decreases over time, while \(Q_R\) initially increases to a maximum value before decaying to its steady-state value. Obviously, the saturation of heat currents occurs more slowly in the asymmetric coupling setting compared to the symmetric one. We find that, due to the additional connection between the qubit 2 and the hot bath, the transient heat current absorbed from the hot bath by the qubits is greater than the heat released to the cold bath. However, this situation alters in the steady-state limit, where the heat exchange with the hot source vanishes and the qubits release heat only to the cold bath.

In Fig. 12, we present the computed dynamical behavior of the thermal rectification factor for the initial state \(|\Phi _1\rangle\) in both the symmetric coupling (Fig. 12a) and asymmetric coupling (Fig. 12b) settings. The Lamb-shift corrections is not included here. Both Fig. 12a,b confirm that, at the equilibrium condition (\(\Delta T=0\)), heat flows through the qubits independent of the temperature gradient’s sign, resulting in \(\Re =2\). The thermal rectification factor \(\Re\) exhibits nonlinear characteristics under non-equilibrium conditions, which are consequences of the behavior of the heat current at each positive and negative temperature bias. In the symmetric coupling setting, \(\Re\) decays oscillatory to zero and a perfect rectification (\(\Re =1\)) is achieved at early times, as shown in Fig. 12a. In the asymmetric coupling setting, however, \(\Re\) experience different dynamics: it initially reaches a maximum, then decreases to near zero, before increasing again to attain a nonzero steady-state value. Therefore, the dynamics of the thermal rectification lasts longer in the asymmetric coupling setting in comparison to the symmetric coupling setting. Another positive aspect of the asymmetry in system-bath couplings is that both the steady-state rectification and the time required to reach the steady state increase with the magnitude of \(\Delta T\), enabling perfect rectification

Dynamics of heat current \(Q_L\) and \(Q_R\) as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B_0=0.6J\), \(\Delta =0.5 J\) and \(T_M=2J\). Here, the initial state of qubits is \(|\Phi _3\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle -|1,0\rangle \right]\) and the Lamb-shift term is not included. The panels (a) and (c) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\), while (b) and (d) correspond to asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\) setting.

when \(\Delta T\) reaches its maximum value.

In Fig. 13, we plot dynamics of \(Q_L\) and \(Q_R\) as a function of Jt for the initial state \(|\Phi _3\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle -|1,0\rangle \right]\), corresponding to the panels of Fig. 11. Based on this figure, the initial state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) results in totally different heat current dynamics. In the symmetric coupling setting, both heat currents \(Q_L\) and \(Q_R\) experience a decaying dynamics to saturate at the steady-state values at each positive and negative temperature bias. In this setting, the heat current received from the hot bath saturates slower (faster) by increasing \(\Delta T\) at the positive (negative) bias. As shown in the panels (a) and (c), the heat flows from the reservoirs to the qubits in the beginning of the evolution, but after a time, the direction of heat transfer from the cold bath to the qubits is reversed and the qubits start to transfer the heat from the hot bath to the cold one. Then, the heat current absorbed (released) from (to) the hot (cold) reservoir increases with time to saturate at the steady-state values. This phenomena is also observed in the asymmetric coupling setting but only for the left bath (see Fig. 13b,d): for \(\Delta T=-T_M\), \(Q_L\) increases with time and reaches a positive maximum value, then decays to saturate at a negative steady-state value. The drawn curves in panels (b) and (d) also show that in the asymmetric coupling setting qubits always absorb heat from the right reservoir for both the positive and negative temperature biases. For temperature gradients \(\Delta T\le 0\), \(Q_L\) increases with time and reaches a maximum value, then decays to saturate at the steady-state values. Obviously, the saturation of heat currents occurs more slowly than in the symmetric coupling setting. As we can see, for the case \(\Delta T= 2T_M\), the qubits never exchange heat with the reservoirs. The physical reason behind this effect is the following: In “Entanglement protection” we proved that in the limit \(T_R\simeq 0\) (\(\Delta T\rightarrow 2T_M\)) and in the regime in which we work (\(B_0\le J+\Delta\)), when the coupling switch is turned on (\(\varepsilon =1\)), the initial state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) remains immune to dissipation, causing the population components \(\rho _{11}\), \(\rho _{22}\) and \(\rho _{44}\) remain zero at all times.

Dynamics of the thermal rectification factor \(\Re\) as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B_0=0.6J\), \(\Delta =0.5 J\) and \(T_M=2J\). Here, the initial state of qubits is \(|\Phi _3\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle -|1,0\rangle \right]\) and the Lamb-shift term is included. The panels (a) and (b) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\) and asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\), respectively.

On the other hand, adjusting \(\varepsilon =1\), and taking the limit as \(T_R\simeq 0\) (\(\Delta T\rightarrow 2T_M\)) in Eq. (12a), results in \(\gamma _{13}^{(R,a)}=\gamma _{13}^{(L,a)}=\gamma _{23}^{(R,a)}=\gamma _{23}^{(L,a)}=0\). By taking into account these considerations, it is straightforward from Eq. (23) that in the asymmetric coupling configuration, for \(\Delta T= 2T_M\), the heat current of the initial state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) remains zero at all times.

In Fig. 14, we display the dynamics of the thermal rectification factor for the initial state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) in both the symmetric coupling (Fig. 14a) and asymmetric coupling (Fig. 14b) settings. Both Fig. 14a,b reaffirm that, at equilibrium condition (\(\Delta T=0\)), heat flows through the qubits, independent of the sign of the temperature gradient, resulting in \(\Re =2\). In the symmetric coupling setting, as shown in Fig. 14a, \(\Re\) shows a monotonic decaying trend: for a given \(\Delta T\), the qubits acts as a thermal rectifier in the beginning of the evolution. After a time, when \(\Re\) decays monotonically to one, the qubits completely block the heat flow in one direction and thus behave as a perfect insulator. Then, as time goes on, the thermal rectification property of qubits gradually weakens again and finally disappears. As can be seen, when the temperature gradient increases to its maximum value, i.e. \(\Delta T=\pm 2T_M\), the qubits completely block the heat flow in one direction at the beginning of the evolution. However, they gradually lose their thermal rectification property over time until the heat flows symmetrically through the qubits.

In the asymmetric coupling setting, however, \(\Re\) follows a different dynamical pattern. In this setting, as illustrated in Fig. 14b,

Dynamics of heat current \(Q_L\) and \(Q_R\) as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B=0.6J\), \(\Delta =0.5 J\) and \(T_M=2J\). Here, the initial state of qubits is \(|\Phi _4\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle +|1,0\rangle \right]\) and the Lamb-shift term is included. The panels (a) and (c) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\), while (b) and (d) correspond to the asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\) setting.

the qubits completely lose their rectification property over time, but immediately regain it until the steady-state is reached. An interesting effect of this asymmetric coupling setting is observed at \(\Delta T=\pm 2T_M\), where the the heat flow is always completely blocked in one direction by the qubits, thus enabling the implementation of a stable thermal diode. In Fig. 15, we plot the dynamics of \(Q_L\) and \(Q_R\) as a function of Jt for the initial state \(|\Phi _4\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle +|1,0\rangle \right]\) in both the symmetric coupling [panels (a) and (c)] and asymmetric coupling [panel (b) and (d)] settings. According to the drawn curves, dynamics of the heat current in the symmetric coupling setting is almost the same as the dynamics in the asymmetric coupling setting. In both symmetric and asymmetric coupling settings, in general, the heat flows from the qubits to the reservoirs in the beginning of the evolution. However, after a certain time, the direction of heat transfer from the qubits to the hot bath is reversed and the qubits start to transfer the heat from the hot bath to the cold one. At this time, the heat current absorbed (released) from (to) the hot (cold) bath increases with time to saturate at the steady-state values. According to the drawn curves, the heat current received from the hot bath saturates slower by increasing \(\Delta T\). Similar to what can be seen for the initial states \(|\Phi _1\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _3\rangle\), the heat current received from the hot bath saturates more slowly (more quickly) as \(\Delta T\) increases at the positive (negative) bias.

Finally, in Fig. 16 we display the dynamics of the thermal rectification factor for the initial state \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) in both the symmetric coupling (Fig. 16a) and asymmetric coupling (Fig. 16b) settings. This figure again confirms that at the equilibrium condition (\(\Delta T=0\)),

Dynamics of the thermal rectification factor \(\Re\) as a function of the dimensionless quantity Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\) by setting \(\kappa =0.05J\), \(B=0.6J\), \(\Delta =0.5 J\) and \(T_M=2J\). Here, the initial state of qubits is \(|\Phi _4\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle +|1,0\rangle \right]\) and the Lamb-shift term is included. The panels (a) and (b) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\) and the asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\), respectively.

the thermal rectification factor gets \(\Re =2\), indicating that, irrespective of the initial state of qubits, the heat flows through the qubits independent of the sign of the temperature gradient. In the symmetric coupling setting, for a given \(\Delta T\), the qubits rectify the heat in the beginning of the evolution. Then, when \(\Re\) suddenly increases to 2, the qubits transfer the received heat to the cold bath independent of the sign of the temperature gradient. After this time, the qubits start to rectify the heat again, completely blocking the heat flow in one direction once \(\Re\) decays to 1. Our results in Fig. 16a show that \(\Re\) eventually decays to zero at the steady state, indicating that qubits lose their rectification property upon reaching that state.

Furthermore, comparing Fig. 16a and b, it may be observed that dynamics of \(\Re\) in the asymmetric coupling setting is similar to the dynamics in the symmetric coupling setting, except in the steady-state limit where \(\Re\) has a nonzero value, indicating that the qubits exhibit thermal rectification. As can be seen, when the absolute temperature gradient increases to \(2T_M\), the steady-state rectification coefficient gets \(\Re =1\), where the qubits completely block the heat flow in one direction, thus realizing a thermal diode.

Before ending this section, we would like to comment on the relationship between the dynamical behavior of thermal entanglement and the phenomenon of heat rectification. By comparing Fig. 3 with 12, Fig. 6 with 14, and Fig. 8 with 16, one can clearly see that there is no a considerable relation between the dynamics of concurrence C and the dynamics of rectification coefficient \(\Re\). However, a close connection between rectification property and entanglement of qubits is observed in the asymmetric coupling setting when the system reaches the steady state. More precisely, for \(\varepsilon =1\), regardless of the initial state of qubits, both C and \(\Re\) reach one in the steady state when the gradient temperature of baths is \(\Delta T=2T_M\). This means that at the higher temperature gradient, qubits leverage the steady-state entanglement between themselves to completely block the heat released from the hot reservoir. This connection between thw steady-state rectification and steady-state entanglement can be explained as follows. As shown in Figs. 4d and 9d, at higher temperature gradient \(\Delta T=2T_M\) once the system reaches the steady-state, population of \(|\Phi _1\rangle\), \(|\Phi _2\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) becomes zero and the system populates exactly at the maximally entangled state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\). This is while, if the temperatures of the left and right reservoirs are interchanged in the reverse direction, the populations \(|\Phi _1\rangle\), \(|\Phi _2\rangle\) and \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) will no longer be zero in the steady-state limit. On the other hand, in the asymmetric setting, we have \(\gamma _{13}^{(L,a)}=0\), \(\gamma _{13}^{(L,e)}=0\), \(\gamma _{23}^{(L,a)}=0\) and \(\gamma _{23}^{(L,e)}=0\), while \(\gamma _{ij}^{(\nu ,a)}\), \(\gamma _{ij}^{(\nu ,e)}\) \((i=1,2;j=3,4)\) are nonzero at \(\Delta T=-2T_M\). Therefore, according to Eq. (23), in the forward direction the heat current \(Q_L(\infty )\) becomes zero. However, in the reverse direction, while the mentioned absorption and emission rates remain zero, the populations of \(|\Phi _1\rangle\), \(|\Phi _2\rangle\), and \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) are no longer zero, resulting in \(Q_L^{r}(t)\ne 0\). This leads to the phenomenon of perfect rectification.

Lamb-shift contribution to the thermal rectification property of qubits

In the previous subsection, we have ignored the Lamb shift correction, i.e. the effective shift of the eigenenergies of the qubits induced by the presence of the baths. The effective shift of the eigenenergies depends on both mean temperature \(T_M\) and gradient temperature \(\Delta T\), thus it may influence the rectification properties of the qubits.

Dynamics of the thermal rectification factor \(\Re\) for different values of \(\Delta T\) with and without the Lamb shift. The initial state of the qubits is \(|\Phi _1\rangle =|0,0\rangle\) and other parameters are set as same as Fig. 12. In the presence of the Lamb shift, the cutoff frequency of the Ohmic spectral density is \(\omega _D=1000 J\). The panels (a) and (b) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\) and the asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\), respectively.

As we now demonstrate, considering this correction allows us to achieve rectification dynamics different from that derived in the previous subsection. It is worth noting that for an Ohmic spectral density, the integrals that appear in Eq. (15) diverge. However, introducing a suitable cutoff frequency \(\omega _D\), resolves this divergence, yielding finite values for the integrals.

In Fig. 17, we illustrate the Lamb-shift contribution to the thermal rectification of the qubit for the initial state \(|\Phi _1\rangle\) in both the symmetric coupling (Fig. 17a) and asymmetric coupling (Fig. 17b) settings. Here, we plot the rectification factor \(\Re\) as a function of Jt for different values of \(\Delta T\) with and without the Lamb-shift in both symmetric and asymmetric coupling configurations. The system parameters are the same as in Fig. 3. Both Fig. 17a and b reveal that, at equilibrium condition (\(\Delta T=0\)), heat current among the qubits remains unaffected by the presence of the Lamb modification. We find that by taking into account the Lamb shift corrections, we attain rectification beyond the bounds derived in the previous sections. As shown in Fig. 17a, Lamb shift prevents qubits from achieving perfect rectification (\(\Re =1\)) in the symmetric setting. This implies that the bath-induced Lamb-shift correction plays a destructive role in the rectification performance of qubits in the symmetric coupling configuration. Conversely, Fig. 17b demonstrates that the Lamb-shift correction has a constructive effect in the asymmetric coupling configuration: for \(\Delta T=\pm T_M\), it increases the number of perfect rectification times and for \(\Delta T=2T_M\), it prolongs the perfect rectification time.

Dynamics of the thermal rectification factor \(\Re\) for different values of \(\Delta T\) with and without the Lamb shift. The initial state of qubits is \(|\Phi _3\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle -|1,0\rangle \right]\) and all other parameters are set as in Fig. 14. In the presence of the Lamb shift, the cutoff frequency of the Ohmic spectral density is \(\omega _D=1000 J\). The panels (a) and (b) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\) and the asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\), respectively.

Dynamics of the thermal rectification factor \(\Re\) for different values of \(\Delta T\) with and without the Lamb shift. The initial state of qubits is \(|\Phi _4\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[ |0,1\rangle +|1,0\rangle \right]\) and other parameters are set as same as Fig. 16. In the presence of the Lamb shift, the cutoff frequency of the Ohmic spectral density is \(\omega _D=1000 J\). The panels (a) and (b) correspond to the symmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =0)\) and the asymmetric coupling setting \((\varepsilon =1)\), respectively.

In Fig. 18, we illustrate Lamb-shift contribution to the thermal rectification of the qubits prepared in the initial state \(|\Phi _3\rangle\) in both the symmetric coupling (Fig. 18a) and asymmetric coupling (Fig. 18b) settings. Here, the system parameters are the same as in Fig. 14. We find that, unlike the symmetric coupling setting, the Lamb-shift correction can change dynamical behavior of rectification in the asymmetric coupling setting. For \(\Delta T=\pm T_M\), as can be seen in Fig. 18b, the Lamb-shift correction although decreases rectification effect of the qubits in the beginning of the evolution, but increases it after a long time. The drawn curves in Fig. 18b also indicate that the Lamb-shift correction does not affect rectification dynamics of the qubits when the gradient temperature is \(\Delta T=0\) and \(\Delta T=2T_M\).

Finally, in Fig. 19, we illustrate Lamb-shift contribution to the thermal rectification of qubit prepared in the initial state \(|\Phi _4\rangle\) in both the symmetric coupling (Fig. 19a) and asymmetric coupling (Fig. 19b) settings. Here, the system parameters are the same as in Fig. 16. According to Fig. 19, the dynamics of rectification is affected by the presence of the Lamb modification only in the asymmetric coupling setting. For \(\Delta T=2T_M\) the Lamb-shift correction prolongs the perfect rectification time, while for \(\Delta T=\pm T_M\) this correction enhances the steady-state rectification performance of the qubits.

Outlook and summary

To summarize, we analyzed the dynamical behavior of quantum features including thermal entanglement, heat current and thermal rectification in a two-qubit XXZ spin chain coupled weakly to two independent Ohmic thermal baths. We considered two different qubit-bath coupling configurations, a symmetric configuration wherein each qubit is coupled to an individual reservoir, and an asymmetric configuration wherein one qubit is coupled to both baths, whereas the another qubit is coupled to just one of them. We showed that, depending on the initial two-qubit state, the asymmetry configuration induced by an extra connection of the hot (cold) bath to one of the qubits, significantly influences the generation, preservation and reviving of these quantum features in high temperature regime, where the system’s coherence dissipates drastically during the evolution. We also explored the stabilizing role of the asymmetry in the system-bath couplings on the thermal rectification properties of various two-qubit initial states and found that, if the qubits start the evolution with each of these initial states, the asymmetry in the system-bath couplings allows the qubits to dynamically recover their lost initial rectification property, and maintain it until the non-equilibrium steady state is reached. Accordingly, a two-qubit thermal diode is realized when the system is relaxed to the non-equilibrium steady state, under the temperature gradient condition \(\Delta T=2T_M\). Additionally, we investigated the Lamb-shift contribution to the thermal rectification property of qubits and found that the rectification performance of qubits can be changed significantly if taking the Lamb shift into account.

Our results represent a novel strategy to control the generation and protection of non-equilibrium thermal entanglement, as well as the quantum heat transport of two-qubit spin chain systems. It goes without saying that this strategy can be generalized to control the entanglement and rectification property of a spin-chain system with more spins and can be easily implemented in the circuit-QED setups, where the two-qubit spin system and thermal baths are implemented by a transmon qudit and two thermal circuits, respectively. In addition, the asymmetry in the qudit-bath coupling can be established by placing some LC circuit band-pass filters between the transmon qudit and one of the thermal circuits.

Data availibility

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

18 September 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17350-1

References

Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M. & Horodecki, K. Quantum entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 865 (2009).

Bennett, C. H. et al. Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 1895 (1993).

Murao, M., Jonathan, D., Plenio, M. B. & Vedral, V. Quantum telecloning and multiparticle entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 59, 156 (1999).

Bennett, C. H. & Wiesner, S. J. Communication via one- and two-particle operators on Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2881 (1992).

Ekert, A. K. Quantum cryptography based on Bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 661 (1991).

Raussendorf, R. & Briegel, H. J. A one-way quantum computer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5188 (2001).

Simon, C. & Kempe, J. Robustness of multiparty entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 65, 052327 (2002).

Yu, T. & Eberly, J. H. Phonon decoherence of quantum entanglement: Robust and fragile states. Phys. Rev. B 66, 193306 (2002).

Dur, W. & Briegel, H. J. Stability of macroscopic entanglement under decoherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 180403 (2004).

Ficek, Z. & Tańas, R. Delayed sudden birth of entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 77, 054301 (2008).

Schlosshauer, M. Decoherence and the quantum to classical transition (Springer, 2007).

Shor, P. W. Scheme for reducing decoherence in quantum computer memory. Phys. Rev. A 52, 2493 (1995).

Cirac, J. I. & Pellizzari, T. Enforcing coherent evolution in dissipative quantum dynamics. Science 273, 1207 (1996).

Carvalho, A., Reid, A. & Hope, J. J. Controlling entanglement by direct quantum feedback. Phys. Rev. A 78, 012334 (2008).

Maniscalco, S., Francica, F., Zaffino, R. L., Gullo, N. L. & Plastina, F. Protecting entanglement via the quantum zeno effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 090503 (2008).

Ba An, N., Kim, J., & Kim, K. Nonperturbative analysis of entanglement dynamics and control for three qubits in a common lossy cavity. Phys. Rev. A 82, 032316 (2010).

Xiao, X., Li, Y., Zeng, K. & Wu, C. Robust entanglement preserving by detuning in non-Markovian regime. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 42, 235502 (2009).

Huang, L.-Y., & Fang M.-F. Protecting entanglement by detuning: in Markovian environments vs in non-Markovian environments. Chin. Phys. B 19, 090318 (2010).

Forozesh, M., Mortezapour, A. & Nourmandipour, A. Controlling qubit-photon entanglement, entanglement swapping and entropic uncertainty via frequency modulation. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136, 778 (2021).

Damodarakurup, S., Lucamarini, M., Di Giuseppe, G., Vitali, D. & Tombesi, P. Experimental inhibition of decoherence on flying qubits via bang-bang control. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 040502 (2009).

Vitali, D. & Tombesi, P. Using parity kicks for decoherence control. Phys. Rev. A 59, 4178 (1999).

Fasihi, M. A. & Mojaveri, B. Protecting the entanglement of two interacting atoms in a cavity by quantum Zeno dynamics. Quantum Inf. Proc. 18, 75 (2019).

Bellomo, B., Franco, R. L. & Compagno, G. Non-Markovian effects on the dynamics of entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 160502 (2007).

Agarwal, G. S. Control of decoherence and relaxation by frequency modulation of a heat bath. Phys. Rev. A 61, 013809 (1999).

Agarwal, G. S., Scully, M. O. & Walther, H. Inhibition of decoherence due to decay in a continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4271 (2001).

Kofman, A. G. & Kurizki, G. Universal dynamical control of quantum mechanical decay: Modulation of the coupling to the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 270405 (2001).

Kofman, A. G. & Kurizki, G. Unified theory of dynamically suppressed qubit decoherence in thermal baths. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 130406 (2004).

Mojaveri, B., Dehghani, A. & Ahmadi, Z. Maximal steady-state entanglement and perfect thermal rectification in non-equilibrium interacting XXZ chains. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136, 1 (2021).

Bellomo, B., Lo Franco, R., Maniscalco, S. & Compagnoet, G. Entanglement trapping in structured environments. Phys. Rev. A 78, 060302 (2008).

Dehghani, A., Mojaveri, B. & Vaez, M. Entanglement dynamics of two coupled spins interacting with an adjustable spin bath: Effect of an exponential variable magnetic field. Quantum Inf. Proc. 19, 1 (2020).

John, S. & Quang, T. Spontaneous emission near the edge of a photonic band gap. Phys. Rev. A 50, 1764 (1994).

Quang, T., Woldeyohannes, M., John, S. & Agarwal, G. S. Coherent control of spontaneous emission near a photonic band edge: A single-atom optical memory device. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 5238 (1997).

Mossberg, T. W., & Lewenstein, M. In Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics, edited by P. R. Berman(Academic, New York, 1994), p. 171.

Yu, T. & Eberly, J. H. Finite-time disentanglement via spontaneous emission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 140404 (2004).

Almeida, M. P. et al. Environment-induced sudden death of entanglement. Science 316, 579 (2007).

Mojaveri, B. & Taghipour, J. Entanglement protection of two qubits moving in an environment with parity-deformed fields. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138, 263 (2023).

Nourmandipour, A., Vafafard, A., Mortezapour, A. & Franzosi, R. Entanglement protection of classically driven qubits in a lossy cavity. Sci. Rep. 11, 16259 (2021).

Altintas, F. & Hardal, A. Ü. C. Quantum correlated heat engine with spin squeezing. Phys. Rev. E 90, 032102 (2014).

Marchukov, O., Volosniev, A., Valiente, M., Petrosyan, D. & Zinner, N. T. Quantum spin transistor with a Heisenberg spin chain. Nat. Commun. 7, 13070 (2016).

Le, T. P., Levinsen, J., Modi, K., Parish, M. & Pollock, F. A. Spin-chain model of a many-body quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 97, 022106 (2018).

Yao, Y. & Shao, X. Q. Optimal charging of open spin-chain quantum batteries via homodyne-based feedback control. Phys. Rev. E 106, 014138 (2022).

Mojaveri, B., Jafarzadeh, R. & Fasihi, M. A. Extracting ergotropy from nonequilibrium steady states of an XXZ spin-chain quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 109, 042619 (2024).

Xue, X. et al. Quantum logic with spin qubits crossing the surface code threshold. Nature 601, 343 (2022).

Shi, X.-F. Rydberg quantum computation with nuclear spins in two-electron neutral atoms. Front. Phys. 16, 52501 (2021).

Lieven M., & Vandersypen, K. Experimental Quantum Computation with Nuclear Spins in Liquid Solution, PhD Thesis, Stanford University (2001).

Loss, D. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Quantum computation with quantum dots. Phys. Rev. A 57, 120 (1998).

Tadokoro, M. et al. Designs for a two-dimensional Si quantum dot array with spin qubit addressability. Sci. Rep. 11, 19406 (2021).

Lozano-Méndez, K., Cásares, A. H. & Caballero-Benítez, S. F. Spin entanglement and magnetic competition via long-range interactions in spinor quantum optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 080601 (2022).

M. A. Nielsen, Ph.D. dissertation, University of New Mexico (1998). arXiv:quant-ph/0011036.

Wang, X. Entanglement in the quantum heisenberg xy model. Phys. Rev. A 64, 012313 (2001).

Wang, X. Threshold temperature for pairwise and many-particle thermal entanglement in the isotropic Heisenberg model. Phys. Rev. A 66, 044305 (2002).

Arnesen, C. M., Bose, S. & Vedral, V. Natural thermal and magnetic entanglement in the 1D Heisenberg model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 017901 (2001).

Kamta, G. L. & Starace, A. F. Anisotropy and magnetic field effects on the entanglement of a two qubit Heisenberg XY Chain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 107901 (2002).

Zhou, L., Song, H. S., Guo, Y. Q. & Li, C. Enhanced thermal entanglement in an anisotropic Heisenberg XYZ chain. Phys. Rev. A 68, 024301 (2003).

Gunlycke, D., Kendon, V. M., Vedral, V. & Bose, S. Thermal concurrence mixing in a one-dimensional Ising model. Phys. Rev. A 64, 042302 (2001).

Kheirandish, F., Akhtarshenas, S. J. & Mohammadi, H. Effect of spin-orbit interaction on entanglement of two-qubit Heisenberg XYZ systems in an inhomogeneous magnetic field. Phys. Rev. A 77, 042309 (2008).

Abbasi, M. R. & Golshan, M. M. Thermal entanglement of a two-level atom and bimodal photons in a Kerr nonlinear coupler. Phys. A 392, 6161 (2013).

Zhang, G.-F. & Li, S.-S. Thermal entanglement in a two-qubit Heisenberg XXZ spin chain under an inhomogeneous magnetic field. Phys. Rev. A 72, 034302 (2005).

Del Cima, O. M., Franco, D. H. T. & Silva, M. M. Magnetic shielding of quantum entanglement states. Quantum Stud. Math. Found. 6, 141 (2019).

Kumar, A., Murch, K. W. & Joglekar, Y. N. Maximal quantum entanglement at exceptional points via unitary and thermal dynamics. Phys. Rev. A 105, 012422 (2022).

Capizzi, L. & Rotaru, A. Thermal entanglement in conformal junctions. J. High Energ. Phys. 2024, 10 (2024).

Wu, K.-H., Lu, T.-C., Chung, C.-M., Kao, Y.-J. & Grover, T. Entanglement Rényi negativity across a finite temperature transition: A Monte Carlo study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 140603 (2020).

Iglói, F. & Tóth, G. Entanglement witnesses in the XY chain: Thermal equilibrium and postquench nonequilibrium states. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 013158 (2023).

Ptaszýnski, K. & Esposito, M. System-bath entanglement of noninteracting fermionic impurities: Equilibrium, transient, and steady-state regimes. Phys. Rev. B 109, 115408 (2024).

Y.-Chen Lin, P.-Yun Yang, W.-Min Zhang, Non-equilibrium quantum phase transition via entanglement decoherence dynamics. Sci. Rep. 6, 34804 (2016).

Eisler, V. & Zimboras, Z. Entanglement in the XX spin chain with an energy current. Phys. Rev. A 71, 042318 (2005).

Bermudez, A., Bruderer, M. & Plenio, M. B. Controlling and measuring quantum transport of heat in trapped-ion crystals. Phy. Rev. Lett. 111, 040601 (2013).

Charalambous, C., Garcia-March, M. A., Mehboudi, M. & Lewenstein, M. Heat current control in trapped Bose-Einstein condensates. New J. Phys. 21, 083037 (2019).

Balachandran, V., Benenti, G., Pereira, E., Casati, G. & Poletti, D. Perfect diode in quantum spin chains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 200603 (2018).

Tacchino, F., Tiago, F. F., Santos, D., Gerace, M. Campisi. & Santos, M. F. Charging a quantum battery via nonequilibrium heat current. Phys. Rev. E 102, 062133 (2020).

Shankar, S. et al. Autonomously stabilized entanglement between two superconducting quantum bits. Nature 504, 419 (2013).

Wang, L. & Li, B. Thermal memory: A storage of phononic information. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 267203 (2008).

Quiroga, L., Rodríguez, F. J., Ramírez, M. E. & París, R. Nonequilibrium thermal entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 75, 032308 (2007).

Sinaysky, L., Petruccione, F. & Burgarth, D. Dynamics of nonequilibrium thermal entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 78, 062301 (2008).

Huang, X.-L., Guo, J.-L. & Yi, X.-X. Nonequilibrium thermal entanglement in three-qubit XX model. Phys. Rev. A 80, 054301 (2009).

Kheirandish, F., Akhtarshenas, S. J. & Mohammadi, H. Non-equilibrium entanglement dynamics of a two-qubit Heisenberg XY system in the presence of an inhomogeneous magnetic field and spin-orbit interaction. Eur. Phys. J. D 57, 129 (2010).

Wang, Z., Wu, W. & Wang, J. Steady-state entanglement and coherence of two coupled qubits in equilibrium and nonequilibrium environments. Phys. Rev. A 99, 042320 (2019).

Sun, Y., Ma, X.-P. & Guo, J.-L. Dynamics of non-equilibrium thermal quantum correlation in a two-qubit Heisenberg XYZ model. Quantum Inf. Proc. 19, 98 (2020).

Orbach, R. Linear antiferromagnetic chain with anisotropic coupling. Phys. Rev. 112, 309 (1958).

Wang, X. Effects of anisotropy on thermal entanglement. Phys. Lett. A 281, 101 (2001).

Baxter, R. J. Exactly solved models in statistical mechanics, Academic London Press, (1982).

Korepin, V. E., Izergin, A. G., & Bogoliubov, N. M. Quantum inverse scattering method and correlation functions, Cambridge University Press, (1993).

Breuer, H. P. & Petruccione, F. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002).

Wootters, W. K. Entanglement of formation of an arbitrary state of two qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2245 (1998).

Wu, L. A., Yu, C. X. & Segal, D. Nonlinear quantum heat transfer in hybrid structures: Sufficient conditions for thermal rectification. Phys. Rev. E 80, 041103 (2009).

Nieuwenhuizen, T. M. & Allahverdyan, A. E. Statistical thermodynamics of quantum Brownian motion: Construction of perpetuum mobile of the second kind. Phys. Rev. E 66, 036102 (2002).

Roberts, N. A. & Walker, D. A review of thermal rectification observations and models in solid materials. Int. J. Thermal Sci. 50, 648 (2011).

Joulain, K., Drevillon, J., Ezzahri, Y. & Ordonez-Miranda, J. Quantum thermal transistor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 200601 (2016).

Ruokola, T., Ojanen, T. & Jauho, A.-P. Thermal rectification in nonlinear quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. B 79, 144306 (2009).

Lambropoulos, P., Nikolopoulos, G. M., Nielsen, T. R. & Bay, S. Fundamental quantum optics in structured reservoirs. Rep. Prog. Phys. 63, 455 (2000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original PDF version of this Article contained errors in the equations. Equations 14, 17 and 19 were omitted and Equations 1, 2, 3(a), 3(b), 3(c), 3(d), 4, 7, (8a), (8b), 9, (10a), 11, (12a), (12b), (13a), (13b), (13c), 15, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 were clipped.

Rights and permissions