Abstract

The geometric configuration of the vertebrobasilar artery (VBA) can influence hemodynamic changes in the posterior circulation. This study aims to analyze the correlation of vascular morphology with posterior circulation infarction (PCI) and high-risk plaques on vessel wall imaging (VWI). A total of 249 atherosclerotic inpatients with 530 plaque segments located in the basilar artery (BA) and vertebral artery (VA) were retrospectively enrolled, comprising 98 PCI and 151 non-PCI patients. The configurations of VBA were classified on VWI and 3-dimensional time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography (3D TOF-MRA), with a further quantitative evaluation conducted on VWI. VWI achieved higher diagnostic accuracy in detecting tuning fork, walking, and lambda VBA configurations, and revealed increased sensitivity in diagnosing VA hypoplasia (VAH), compared to TOF-MRA. Higher proportions of PCI and high-risk plaques were observed in the lambda and walking configurations than the tuning fork. No statistical difference in VAH was observed between the PCI and non-PCI groups (P = .972). Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that high-risk plaque [odds ratio (OR) = 1.997 (1.039–3.837), P = .038], the mean diameter of bi-VAs [OR = 1.557(1.012–2.395), P = .044], and the grade of BA lateral position [OR = 1.416 (1.029–1.950), P = .033] were independent risk factors associated with PCI. High-risk plaque segments featured larger vascular diameter, wall area, normalized wall index (NWI), remodeling index (RI), plaque volume, BA-midline, and vessel length compared with those with low-risk plaques (all P < .05). VWI offers the dual advantages of observing vascular morphology and evaluating high-risk plaques, which aids in the timely identification of individuals with PCI risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of mortality worldwide, with ischemic stroke being the most common type1. According to the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association, approximately 795,000 people suffer with a stroke each year, of which 690,000 are ischemic2. And atherosclerosis is the primary cause of ischemic stroke3. Posterior circulation infarction (PCI) accounts for approximately 20-25% of all ischemic strokes, occurring mainly in the brainstem, cerebellum, and parts of the occipital and temporal lobes, which is closely related to the vertebrobasilar artery (VBA) system4,5. Embolism is reported more common in posterior circulation area6, and PCI is considered to have a higher risk of recurrent stroke and worse outcomes compared to anterior circulation infarction (ACI)7. The geometric configurations of the VBA have been reported to affect vessel hemodynamics of posterior circulation, mainly by varying the radius, curvature, length, and angles among VBAs8,9,10,11. The velocity of blood changes in the irregular or stenotic region of vessels and improves the transformation between pressure and kinetic energy12, potentially causing plaque migration and blood clot formation, thus further increasing the risk of plaque rupture and PCI. A cohort study13 demonstrated that the morphology of VBA was associated with the risk of PCI recurrence and mortality. Meanwhile, a research14 indicates that individuals with PCI or vertebrobasilar artery syndrome tend to be younger compared to those with ACI, and the former ones often have a smaller diameter in bi-VAs. When a vertebral artery is equal to or less than 2–3 mm in diameter, it is reported as vertebral artery hypoplasia (VAH)15,16. Large-sample studies have demonstrated that VAH is an independent risk factor for PCI, especially in patients under 65 years old14,16. Therefore, given the high prevalence and serious outcomes associated with PCI, particularly in younger individuals with peculiar vertebrobasilar artery characteristics, further research into the relationship between VBA morphology and PCI or plaque vulnerability is critical.

An accurate evaluation of imaging of the intracranial artery is essential for stroke prevention and treatment. Conventional cerebrovascular imaging techniques, mainly including digital subtraction angiography (DSA), computed tomography angiography (CTA), and time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography (TOF-MRA), diagnose vascular diseases by visualizing blood flow and assessing lumen stenosis. However, these methods have a limited ability to evaluate tiny lesions on the vessel wall as they primarily focus on the arterial lumen, rendering the vessel wall largely invisible—particularly in cases of positively remodeled atherosclerotic plaques without luminal stenosis3,17. High-resolution MR vessel wall imaging (VWI) is based on black-blood imaging to suppress blood flow signals in the lumen, and advanced VWI technologies, such as sample perfection with application-optimized contrasts using varying flip angle evolutions (SPACE) and Cube, are being increasingly applied in clinical practice18. These techniques offer substantial improvements in spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio, which are particularly useful in detecting atherosclerotic plaques, identifying high-risk (vulnerable) plaques, and demonstrating the morphologic features of vessels19,20,21. VWI offers two key advantages over conventional vascular lumen imaging techniques like DSA, CTA, and TOF-MRA: it enables the detection of non-stenotic vascular pathologies within the vessel wall and provides detailed characterization of stenotic lesions already identified by traditional angiographic methods22. Besides, while VWI incorporates thin-slice T1-weighted imaging with and without contrast, it differs significantly from conventional T1-weighted imaging by being specifically optimized to evaluate the vessel wall, suppressing luminal signals and enhancing vessel wall visualization. This makes VWI an indispensable tool in diagnosing cerebrovascular diseases, particularly in analyzing vessel wall configurations, detecting non-stenotic plaques, identifying vessel wall lesions, and providing detailed insights into their pathological course.

Previous VWI studies mainly focused on the association between VBA geometric configuration and atherosclerotic plaque characteristics, and often conducted during the acute phase of cerebral infarction21,23. However, these studies have not fully validated the accuracy of VWI in vascular morphology assessment or the association between VBA morphology and PCI during the overall infarct period or high-risk plaques. Also, studies on the use of VWI in evaluating VAH are limited. Therefore, our study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of high-resolution VWI in assessing VBA morphology. Specifically, this study sought to determine whether certain VBA configurations are associated with an increased risk of PCI and the presence of high-risk atherosclerotic plaques. We hypothesized that specific morphological characteristics may serve as independent risk factors for PCI and be related to plaque vulnerability.

Methods

Patients

From January 2018 to December 2021, 536 inpatients in neurology department of the Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University were enrolled. The sample size was determined by considering previous VWI studies and accounting for data exclusion criteria. All patients were with neurologic symptoms and subjected to laboratory and imaging tests within 1 week of hospitalization. This was a retrospective case–control study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) atherosclerosis of the BA and/or VA (V4 segment) detected using VWI, (2) all patients performed a TOF-MRA or CTA examination before VWI, (3) durations of neurological symptom onset and exams time within six months, and (4) complete baseline data of clinical information and laboratory examinations. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) combined with non-atherosclerotic vascular diseases, including intracranial arterial thrombosis (n = 100), cerebral venous thrombosis (n = 61), arteritis (n = 9), arterial dissection (n = 28), aneurysm (n = 5), vascular malformations (n = 20), and moyamoya disease (n = 25); (2) with potential cardiogenic embolic factors, such as atrial fibrillation, precordial heart disease, and infective endocarditis (n = 10); (3)internal carotid artery stenosis > 50% or occlusion (n = 9); (4) poor image quality or incomplete images(n = 11); and (4) with no confluence VBA configuration (n = 9). Finally, 249 patients with 530 atherosclerotic VBA segments were included in this study. Of these, 98 with infarction in the cerebellar and/or brainstem, detected by routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) protocols, were assigned to the PCI group, and the other 151 patients without PCI were included in the non-PCI group. Among the PCI patients, 43 acute-phase infarcts exhibited high signals on DWI, while 55 non-acute-phase infarcts displayed low signals on DWI. Additionally, 192 participants underwent both the 3-dimensional (3D) TOF-MRA and VWI, and the diagnostic accuracy of VWI on VBA configurations was compared with that of TOF-MRA. The reference standard was a comprehensive combination of TOF-MRA and VWI. The remaining 57 patients performed a CTA examination before VWI. Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart of the patient selection strategy for this study. The demographic data and laboratory tests for risk factors of atherosclerotic or stroke in the enrolled patients are demonstrated in Table 1. Protocols of this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University (KY2024-118-01). This study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

MRI protocols

MR images were acquired on 3T MR scanners (MAGNETOM Verio Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany, or Discovery MR750w, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, USA) with a 32-element head coil array. Routine clinical MRI protocols for stroke assessment included T1-weighted (T1W) imaging, T2-weighted (T2W) imaging, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). 3D TOF-MRA was performed prior to contrast. SPACE or Cube sequences were conducted both pre- and post-contrast. The parameters for 3D TOF-MRA images were as follows: repetition time = 21.0 ms, echo time = 3.6 ms, field of view = 200 × 200 mm2, slice thickness = 0.6 mm, voxel size = 0.8 × 0.5 × 0.6 mm3, and matrix size = 261 × 384. The VWI protocols included pre- and post-contrast 3D T1W SPACE images (repetition time = 600 ms, echo time = 14 ms, flip angle = 120°, slice thickness = 0.8 mm, matrix size = 264 × 384, field of view = 210 × 210 mm2, resolution/voxel size = 0.8 × 0.5 × 0.8mm3, and scan time = 8 min), or 3D T1W Cube imaging (repetition time = 600 ms, echo time = 14 ms, flip angle = 90°, slice thickness = 0.8 mm, matrix size = 384 × 384, field of view = 256 × 256 mm2, resolution/voxel size = 0.7 × 0.7 × 0.8mm3, and scan time = 7 min). A contrast agent was used (gadobutrol Gadovist 1.0 at 0.1 mmol/kg; Schering, Basel, Switzerland).

Geometric configurations of VBAs and VWI-based plaque classification

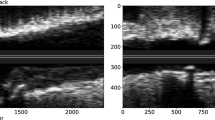

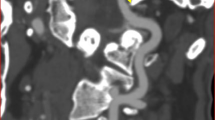

VBA morphology and plaque classifications were evaluated by 2 radiologists (J.X. and M.L., with 8 and 4 years of experience in neurologic VWI, respectively) blinded to patients` information, and disagreement between the observers was resolved by a consistency test or with consensus. VWI data were analyzed using Syngo.via (Siemens Healthineers) with reconstruction of 1.0-mm slice thickness and 1.0-mm intervals. On TOF-MRA or VWI, VBAs were arranged into 4 configurations and bi-VAs of the former 3 types emerged into BA21,24,25: (a) tuning fork: bi-VAs were equal in diameter (< 0.3 mm in difference) and bent in opposite directions to form a symmetrical confluence (Fig. 2a-c); (b) walking: bi-VAs were equal in diameter and bent in the same direction (Fig. 2d-f); (c) lambda: bi-VAs with a diameter difference of \(\:\ge\:\:\)0.3 mm, regardless of the displacement of VBAs (Fig. 2g-i); and (d) no confluence: VAs were not confluent, with one of these extending into the BA and another into other arteries. The no configuration was excluded from this study mainly due to its special vascular composition and rare incidence. VAH was defined as conditions in which the diameter of the VA was \(\:\le\:\)2 mm, with the contralateral larger VA as the dominant VA26. Plaques of VBAs were identified and analyzed on VWI combined with axial, coronal, and sagittal images. The high-risk plaques were defined as those which met with at least 1 of the following 2 features19,27,28,29: (a) hyperintense signal in plaques on pre-contrast T1W images: signal intensity of the brightest spot >150% compared with the normal vessel wall; (b) strong enhancement: similar to or greater than that of the pituitary infundibulum, as depicted in Fig. 3a and b. Otherwise, the plaques were defined as low-risk plaques.

3D TOF-MRA, coronal, and sagittal pre-enhanced T1W VWI images of tuning fork (a–c), walking (d–f), and lambda (g–i) configurations of VBA, presented sequentially. Arrows indicate BAs, and arrow heads indicate left and right VAs. The rectangle labeled stenosis of BA lumina resulted from atherosclerotic plaque (d,e). 3D TOF-MRA 3-dimensional time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography, T1W T1-weighted, VWI vessel wall imaging, VBA vertebrobasilar artery, BA basilar artery, VA vertebral artery.

High-risk plaque of the right VA (arrow) featured as an iso-intense signal on pre-enhanced T1W image and obviously enhanced post-contrast, and that of the left VA (arrowhead) characterized as a hyperintense signal on pre-enhanced T1W image and insignificantly enhanced post-contrast (a,b). Clip angles between bi-VAs (VAJ), BA and right VA (VBJR), and BA and left VA (VBJL) were measured on the coronal images (c). BA basilar artery, VA vertebral artery, T1W T1-weighted.

Assessment and quantitative indicators of morphologic features and plaques of VBA on VWI

Based on patients, the diameters of the outer edges of the proximal, middle, and distal VBAs were measured and averaged on the reconstruction images. Mean value and diameter difference of bi-VAs were calculated. The outer contour area (vessel area) and lumen area of the VBAs were measured and averaged using the same methodology described above. The remodeling index (RI) = vessel area /reference vessel area28,29, with the adjacent normal vessel as reference. Based on plaque segments, the diameter of outer edge of the vessel, vessel area, lumen area and RI were measured and calculated by manually tracing at the level of the unique plaque or that of the most narrowed lumen when multiple plaques existed on the axial image. Wall area = vessel area-lumen area. Normalized wall index (NWI) = wall area/vessel area*100%28. Plaque volume was calculated using the ITK-SNAP software (version 4.0.1, http://www.itksnap.org)30. The distance from the outermost edge of the BA to the midline of the brainstem (BA-midline) was measured. Vessel lengths were measured along the virtual mid-axis of the vessels, from the origin to the terminus point, using curved reconstruction images. The tortuosity index was calculated as the ratio between the true vessel length and the straight-line distance between the origin and terminus31. The lateral position of the BA was evaluated on axial images and graded as 0: midline, 1: midline or probably off midline, 2: definitely displaced to the side, or 3: reaching the cerebellopontine angle32,33. The height of the BA bifurcation was evaluated by combining axial and sagittal images and graded as 0: at or below the dorsum sellae, 1: at the level of suprasellar cistern, 2: at the level of the third ventricle floor, and 3: indenting and elevating the third ventricle floor32,33. The clip angles between bi-VAs (VAJ), BA and right VA (VBJR), and BA and left VA (VBJL) were measured on the coronal images, as illustrated in Fig. 3c. All continuous variables were measured 3 times by 1 observer (M.L.) and the average value was applied. The categorical variables were evaluated by two observers (J.X. and M.L.) and any disagreement was resolved with consensus.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics v29.0 (IBM Corporation, NY, USA). Continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range as M (Q25, Q75). Continuous variables in the 2 groups were compared using an independent-sample t test or the Mann–Whitney U test. The categorical variables were evaluated using the χ2 test for comparison between the 2 groups. The rank variables were evaluated and analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. A Cohen’s Kappa test was used to evaluate the agreements between the 2 observers in classifying the VBA morphology, or to analyze the consistency between VWI or TOF-MRA with the reference techniques, and the diagnostic accuracy was computed with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Consistency was considered good if the κ value is ≥ 0.75, unsatisfactory if the κ value is < 0.40, and otherwise moderate. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the risk factors of PCI, estimating the odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs. Variables for univariate analysis were selected based on the potential clinical relevance in PCI. Variables that show statistical significance (P < .05) in the univariate analysis were included as predictors in the multivariate analysis. A two-tailed P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline clinical data of patients

Of the 249 patients included in this study, 98 were classified into the PCI group, comprising 24 women and 74 men, with an average age of 61.86\(\:\:\pm\:\:\)11.30 years. The remaining 151 patients in the non-PCI group comprised 44 women and 107 men, with an average age of 61.25\(\:\pm\:\)11.69 years. The duration of clinical symptoms onset and examinations for all participants was 18.90 \(\:\pm\:\) 38.22 days, with a median of 4 days for the PCI group and 7 days for the non-PCI group. No statistically significant difference was observed in age, sex, durations of symptom onset and exams time, history of hypertension, smoking, alcoholism, or diabetes between the 2 groups (all P > .05). The activated partial thromboplastin (APTT) and prothrombin time (PT) levels were higher in the PCI group compared with the non-PCI group (P = .042 and.039, respectively). However, no statistically significant difference was noted between the 2 groups in thrombin time (TT), international normalized ratio (INR), fibrinogen (Fbg), triglycerides cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), apolipoprotein (Apo)-A, and Apo-B (all P > .05), as depicted in Table 1.

Accuracy of VWI and 3D TOF-MRA in assessing VBA geometric configurations

VWI achieved a higher degree of agreement with the reference standard in classifying tuning fork, walking, and lambda VBA geometric configurations compared with 3D TOF-MRA [\(\:\kappa\:\:\)= 0.960 (0.925–0.995), P < .001 vs. \(\:\kappa\:\:\)= 0.880 (0.821–0.939), P < .001]. For diagnosing VAH, VWI exhibited greater consistency with the reference standard compared with 3D TOF-MRA [\(\:\kappa\:\:\) = 0.928 (0.871–0.985), P < .001 vs. \(\:\kappa\:\:\)= 0.819 (0.735–0.903), P < .001]. Moreover, VWI demonstrated a considerably higher sensitivity (95.1% vs. 80.0%) and slightly lower specificity compared with TOF-MRA (97.7% vs. 99.2%) in diagnosing VAH, as demonstrated in Table 2. In 15 patients, a lambda configuration or VAH was misdiagnosed by TOF-MRA, presenting false-positive results due to luminal narrowing caused by VA atherosclerosis. This indicated that VWI may be superior in assessing the diameter of vessels with atherosclerosis compared with TOF-MRA. In 4 patients, vascular tortuosity was misjudged by VWI but accurately assessed by TOF-MRA, which suggested that TOF-MRA may be a more direct method for vessel tortuosity observation.

Morphologic features and quantitative analysis of VBAs associated with PCI

Based on VWI findings presented in Table 3, the percentage of patients with PCI was higher in walking (44.9%) and lambda (40.4%) configurations than in the tuning fork configuration (34.1%); however, no statistically significant difference was observed between the PCI and non-PCI groups (\(\:\chi\:\)2 = 2.009, P = .366) with a high coherence between observations [\(\:\kappa\:\:\)= 0.877 (0.853–0.901), P < .001]. Patients with or without VAH demonstrated no statistically significant difference in PCI incidence (\(\:\chi\:\)2 = 0.001, P = .972) with a good coherence between observations [\(\:\kappa\:\:\)= 0.790 (0.753–0.827), P < .001]. Quantitative analysis showed that diameter of the left VA, mean diameter of bi-VAs, and difference in diameter of bi-VAs were all greater in patients with PCI than in those without PCI (t = 2.951 and P = .003; t = 3.355 and P < .001; U = 6194.5 and P = .030, respectively). The vessel area, lumen area, and RI of the three arteries demonstrated no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups (all P > .05). The tortuosity index of the right VAs was greater in the non-PCI group compared with the PCI group (U = 5672.0, P = .002). In contrast, the grade of BA lateral position tended to be higher in the PCI group than in the non-PCI group (U = 6245.0, P = .028). No statistically significant difference was observed in BA-midline, grade of BA bifurcation height, vascular length, or angles of VBAs between the 2 groups (all P > .05). Furthermore, as shown in Table 4, the multivariable logistic regression analysis results demonstrated that high-risk plaque [odds ratio (OR) = 1.997 (1.039–3.837), P = .038], mean diameter of bi-VAs [OR = 1.557(1.012–2.395), P = .044], and the grade of BA lateral position [OR = 1.416 (1.029–1.950), P = .033] were independent risk factors associated with PCI. Whereas, tortuosity index of RVA [OR = 0.015 (0.001–0.263), P = .004] may have a protective effect to PCI.

Morphologic features of atherosclerotic VBA segments associated with plaque vulnerability

Based on 530 atherosclerotic VBA segments (122 BAs and 408 VAs; 314 of high-risk and 216 of low-risk plaque group), the percentage of segments with high-risk plaque gradually decreased in walking (61.2%), lambda (60.0%), and tuning fork (57.5%) configurations, although no statistically significance difference was noted among these configurations between the 2 groups (\(\:\chi\:\)2 = 0.561, P = .730) (Table 5). Diameter of the outer edge of target segments, wall area, NWI, RI, and plaque volume were larger in the high-risk plaque segments compared with the low-risk plaques (t = 4.388, P < .001; t = 3.205, P < .001; U = 28932.0, P = .005; t = 2.232, P = .026; and U = 25433.0, P < .001, respectively). The BA-midline was also larger in the high-risk plaque segments than in the low-risk group (U = 30204.0, P = .032), indicating that BA tortuosity in the former group was more obvious. Besides, the length of VBA segments was larger in the high-risk plaque group than in the low-risk (U = 22466.000, P < .001). Yet, no statistically significant difference in the segmental lumen area, tortuosity index, or angles of VBAs was observed between the 2 groups (all P > .05).

Discussion

This study focused on revealing the relationship between VBA morphology and PCI and high-risk plaques using VWI. Firstly, we proved that VWI demonstrated a higher agreement with the reference standard in the morphologic assessment of VBAs and a higher sensitivity in detecting VAH, compared with 3D TOF-MRA. The percentages of patients with PCI or segments with high-risk plaques were both higher in the lambda or walking configurations than that in the tuning fork configuration. However, no statistically significant difference was noted among the three configurations, nor in patients with or without VAH (both P > .05). Then, quantitative analysis found that the diameter of the left VA, the mean or difference in diameter of bi-VAs, and the BA-midline distance were larger, and the lateral position of BA was of a higher grade in patients with PCI than those in the non-PCI group (all P < .05). Furthermore, multivariable logistic regression analysis demonstrated that high-risk plaque [odds ratio (OR) = 1.997 (1.039–3.837), P = .038], the mean diameter of bi-VAs [OR = 1.557(1.012–2.395), P = .044], and the grade of BA lateral position [OR = 1.416 (1.029–1.950), P = .033] were independent risk factors associated with PCI. Besides, the vascular diameter, wall area, NWI, RI, plaque volume, BA-midline, and vessel length were all larger in high-risk plaque segments compared with the low-risk ones (all P < .05). These findings underscored the advantages of VWI in evaluating high-risk vascular morphology of PCI and extracting segmental characteristics with vulnerable plaques.

Compared to TOF-MRA, primarily focusing on vascular lumen and blood flow signals, VWI provides significant advantages by directly visualizing the vessel wall. This enables the detection in morphology of vessel wall and a more accurate determination of vascular disease etiology. As a localizer for subsequent VWI20,34, TOF-MRA directly demonstrates the VBA morphology, but it cannot evaluate critical wall metrics, such as the outer diameter or area of the outer edge of vessels. Furthermore, TOF-MRA is susceptible to false positives and inaccuracies in assessing stenosis severity, such as misdiagnosing subtotal occlusions as complete occlusions or overestimating stenosis severity due to signal loss from spin dephasing or slow blood flow22. Particularly, VWI in this study was more suitable than TOF-MRA for assessing vascular diameter in atherosclerosis to avoid false-positive diagnosis of VAH, which was vital to accurately distinguish because of the varied atherosclerotic burdens35. Sarikaya et al.36 also demonstrated that VWI could be more reliable for quantitative evaluation than MRA in stenosis measurement. Therefore, VWI is more reliable for assessing vascular morphology in atherosclerosis, avoiding the false positives and limitations inherent to TOF-MRA.

Given the challenges of obtaining direct pathological samples of intracranial vascular lesions due to the unique anatomy of cranial blood vessels, cerebrovascular imaging plays a critical role in their assessment. As a complementary modality to TOF-MRA, VWI offers precise characterization of vascular lesions and accurate identification of the etiology of lumen narrowing, such as atherosclerotic plaques, thrombosis, vasculitis, and arterial dissections20. In particular, VWI has unparalleled value in assessing atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability. High-risk plaques have distinct structural and compositional features that render them unstable and more likely to cause thrombosis and infarction after rupture. These features mainly include thick and positive remodeling plaques (suggesting larger plaques), surface irregularities (indicating fibrous cap rupture), intraplaque hemorrhage (manifested as T1 shortening), and remarkable enhancement post contrast on VWI (suggesting a marker of inflammation and neovascularization)27,37,38,39. TOF-MRA may underestimate the risk of positive remodeling plaques during PCI because of insignificant luminal narrowing, whereas VWI could effectively detect these higher-risk plaques20. Meanwhile, VWI can acquire metrics indicating risk of rupture, such as plaque volume and remodeling index, which cannot be measured on TOF-MRA. Furthermore, VWI enables analysis of composition of the identified plaques, realizing extraction of vascular morphological features and quantitative evaluation for target segments with high-risk palques40. These unique capabilities of VWI allow for potentially improved stroke risk prediction, comprehensive lesion monitoring, and long-term follow-up for infarction and atherosclerosis.

Previous studies identified 4 VBA configurations: tuning fork, walking, lambda, and no confluence25,41. The tuning fork configuration, with symmetrical bifurcation and parallel flow, demonstrated a lower plaque prevalence due to fewer hemodynamic disturbances and a centrally peaked velocity profile of VBAs24. In contrast, the walking and lambda configurations, with asymmetries and altered flow patterns, were linked to increased intracranial atherosclerotic disease and PCI risk21,42,43. In this study, the lambda and walking configurations contributed to higher proportions of PCI and high-risk plaques compared with the tuning fork. The pathogenesis potentially involves reduced shear stress, slower blood flow velocity, and increased blood flow resistance by altering the radius, curvature, length, and angulation of VBAs13,25,44. Besides, the no confluence VBA configuration (n = 9) was excluded due to its rarity, as the study focused on clinically prevalent configurations with larger sample sizes (tuning fork, n = 91; walking, n = 69; lambda, n = 89). Meanwhile, the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between vascular configuration and ischemic stroke, so it is influenced by the number of major blood-supplying vessels in the posterior circulation. Additionally, missing quantitative data, such as BA length and the angle between the unconfluent VA and BA, further supported its exclusion. However, previous studies13,21 have included the “no confluence” type, either to explore the association between vascular configuration and plaque formation or distribution, or due to sufficient sample sizes allowing robust comparative data analysis. Future research with larger cohorts could enable robust subgroup analyses to understand these unique characteristics of VBAs and clinical relevance.

Generally, VAH was defined as a 2–3 mm range14, however, recent researches over the past three years has consistently adopted a threshold of 2 mm26,45. Aligning with this trend, our study chose the 2 mm cutoff of VAH to ensure consistency with recent literature, enhance specificity, and reduce misclassification of borderline cases. A large sample retrospective study46 demonstrated that VAH was an independent risk factor for posterior circulation atherosclerosis (OR = 10.804, 95% CI = 6.273–18.606, P < .001). The low shear stress in the walls of dysplastic vertebral arteries induces phenotypic changes in endothelial cells, which promotes the onset and progression of atherosclerosis and the probability of vascular thrombosis47. However, in our study, no statistically significant difference in PCI occurrence was noted between patients with and without VAH (P > .05). The discrepancy between our findings and previous studies identifying VAH as an independent predictor of PCI may stem from several factors. First, prior studies primarily focused on acute ischemic stroke patients46, whereas we examined VAH-PCI associations across all clinical phases. Second, our stricter 2 mm threshold for VAH definition aligns with recent literature, enhancing specificity and minimizing misclassifications. Third, we utilized VWI for VAH diagnosis, providing clearer outer wall contours and more accurate vessel morphology assessments. This approach may be superior to transcranial doppler (TCD) used in prior studies48,49 in evaluating morphology of VAH, because TCD poorly visualizes the intracranial segment of the vertebral artery due to skull transmissibility and probe angle limitations. Additionally, studies26,50 using CTA and MRA rely on lumen imaging, assessing VAH based on vascular lumen morphology. In cases of severe arterial wall pathology causing lumen stenosis, lumen-based imaging may lead to false-positive VAH diagnoses. So, we believe that VWI is more appropriate for evaluating congenital variants, such as VAH, because the vessel morphology is judged on the basis of the wall rather than the lumen. We will further explore these factors in the future.

Quantitative analysis further proved our findings. First, blood flow increased exponentially with vessel radius8, and a small diameter reduced vascular capacity for clearing clots51. Whereas, positive remodeling plaques, characterized by a larger lipid core, thinner fibrous cap, and more inflammatory components, may effectively indicate the risk of ischemic events instead of stenosis52. The majority of the target plaques exhibited as positive remodeling in this study, with the values of RI ≥ 1.0528,29. High-risk plaque was independent risk factors to PCI [OR = 1.997 (1.039–3.837), P = .038] and associated with a larger diameter, wall area, NWI, RI, and plaque volume compared with the low-risk plaques (all P < .05). Meanwhile, the asymmetry of both VAs (diameter or flow rate differences) can increase the turbulence of blood in BA24, promoting atherosclerosis and PCI. Our study found that PCI patients charactered as larger mean or difference in diameter of bi-VAs (both P < .05), and the mean diameter of bi-VAs was an independent risk factor [OR = 1.709 (1.115–2.618), P = .014]. Besides, in this study, we observed that some vessels exhibited similar diameters but different vessel or lumen areas between the two groups. These differences in area can be attributed to plaque distribution, arterial remodeling, and non-circular vessel geometry. Plaque burden or asymmetry impacts lumen area, while irregular vessel shapes mean that unidimensional diameter measurements may not accurately reflect the entire cross-sectional geometry3,17,53.

Second, the vessel radius and curvature considerably impacted VBA hemodynamics by altering wall shear stress8,9, and the perforating artery may be stretched and compressed by the curved BA, promoting vasospasm and ischemia54. Our study identified BA lateral position as an independent PCI risk factor [OR = 1.461 (1.071–1.993), P = .017], and the high-risk plaque segments demonstrated a more obvious tortuosity (larger BA-midline) than the low-risk ones (P = .032). Similarly, previous studies21,43 suggested that a large diameter difference between bilateral VAs, ≥ 3 bends, or considerable tortuosity of the VBAs contributed to the formation of atherosclerosis plaques. Third, progressive elongation of the VBAs may influence tortuous flow patterns, disrupting hemodynamics and promoting plaque accumulation10. VBA segments with high-risk plaques were longer than low-risk ones (P < .001). In addition, Kim et al.11 demonstrated that a larger angle between the dominant VA and BA in patients with pontine infarction increased plaque formation, and Li et al.55 noted that the mid-BA angle could raise pontine infarction incidence. However, no statistically significant differences in measured angles were observed in this study (all P > .05), potentially due to various angular choices. Thus, our findings validated that the diameter, tortuosity, and vessel length of VBAs have a prominent impact on PCI and plaque vulnerability.

This study had certain limitations. Firstly, in a few cases of lambda configurations, bi-VA asymmetry and vascular tortuosity coexisted, whose synergies associated with PCI or plaque vulnerability need to be further explored. Secondly, certain findings in this study indicated a left or right VA dominance, which may be related to the lateral dominance of the VAs and requires further exploration. Additionally, CTA was utilized for 57 patients instead of MRA due to clinical needs and financial considerations. For the expanded analysis exploring the association of VWI findings with PCI or high-risk plaques, all patients with available VWI data were included. This approach maximized the dataset, but it may introduce variability in imaging modalities. Finally, further prospective studies are needed to reveal the relationship between VBA configurations and the progression of plaque vulnerability or PCI recurrence.

In conclusion, this study validated the accuracy of VWI in assessing VBA configurations and highlighted its advantages in identifying high-risk vascular morphology and vulnerable plaques. These findings will contribute to the stratification of stroke risk and significantly impact on clinical guidelines and treatment protocols for stroke prevention and management. Ultimately, this will be a step towards accurate diagnosis and treatment of PCI.

Data availability

The datasets used during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Koutsaliaris, I. K. et al. Oxidative stress, vascular aging and atherosclerotic ischemic stroke. Curr. Med. Chem. 29, 5496–5509. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867328666210921161711 (2022).

Kleindorfer, D. O. et al. Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 52, e364-e467. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000375 (2021).

Gomyo, M., Tsuchiya, K. & Yokoyama, K. Vessel wall imaging of intracranial arteries: fundamentals and clinical applications. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 22, 447–458. https://doi.org/10.2463/mrms.rev.2021-0140 (2023).

Sparaco, M., Ciolli, L. & Zini, A. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke-a review part I: anatomy, aetiology and clinical presentations. Neurol. Sci. 40, 1995–2006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-019-03977-2 (2019).

Salerno, A., Strambo, D., Nannoni, S., Dunet, V. & Michel, P. Patterns of ischemic posterior circulation strokes: A clinical, anatomical, and radiological review. Int. J. Stroke. 17, 714–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930211046758 (2022).

Kim, J. S. et al. Risk factors and stroke mechanisms in atherosclerotic stroke: intracranial compared with extracranial and anterior compared with posterior circulation disease. Stroke 43, 3313–3318. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.658500 (2012).

Liu, H. et al. Stroke recurrence and antiplatelets in posterior versus anterior circulation minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke 54, 964–972. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.041738 (2023).

Hiller, A., Davis, J., Schulz, S., Henderson, J. & Wilhelmi, B. J. Recipient vessel selection in head and neck reconstruction. Eplasty 17, e42 (2017).

Woo, H. G. et al. Wall shear stress associated with stroke occurrence and mechanisms in middle cerebral artery atherosclerosis. J. Stroke. 25, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2022.02754 (2023).

Ngo, M. T., Kwak, H. S. & Chung, G. H. Change in Basilar artery length and bending according to aging and vertebral artery dominance: A longitudinal study. Sci. Rep. 10, 8904. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65682-x (2020).

Kim, B. J. et al. Basilar artery plaque and Pontine infarction location and vascular geometry. J. Stroke. 20, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2017.00829 (2018).

Hademenos, G. J. & Massoud, T. F. Biophysical mechanisms of stroke. Stroke 28, 2067–2077. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.28.10.2067 (1997).

Qu, M. et al. Association between vertebrobasilar artery geometry and vertebrobasilar stenosis, recurrence, and death in posterior circulation stroke and transient ischemic attack. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 32, 107306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2023.107306 (2023).

Vilimas, A., Gaigalaite, V., Urbonas, M. & Jatuzis, D. Association of vertebral artery hypoplasia and vertebrobasilar cerebrovascular accident. Medicine. 58 https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58091189 (2022).

Mitsumura, H. et al. Relationship between vertebral artery hypoplasia and posterior circulation ischemia. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 25, 266–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.09.027 (2016).

Zhang, D. P. et al. Vertebral artery hypoplasia, posterior circulation infarction and relative hypoperfusion detected by perfusion magnetic resonance imaging semiquantitatively. J. Neurol. Sci. 368, 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2016.06.043 (2016).

Yang, H. et al. High-resolution magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging provides new insights into Moyamoya disease. Front. Neurosci. 18, 1375645. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2024.1375645 (2024).

Bapst, B. et al. Post-contrast 3D T1-weighted TSE MR sequences (SPACE, CUBE, VISTA/BRAINVIEW, IsoFSE, 3D MVOX): technical aspects and clinical applications. J. Neuroradiol. 47, 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurad.2020.01.085 (2020).

Saba, L. et al. Carotid Plaque-RADS: A novel stroke risk classification system. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 17, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2023.09.005 (2024).

Mandell, D. M. et al. Intracranial vessel wall MRI: principles and expert consensus recommendations of the American society of neuroradiology. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 38, 218–229. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4893 (2017).

Zheng, J. et al. Association between the vertebrobasilar artery geometry and Basilar artery plaques determined by high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Neurosci. 22 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12868-021-00624-5 (2021).

Lindenholz, A., van der Kolk, A. G., Zwanenburg, J. J. M. & Hendrikse, J. The use and pitfalls of intracranial vessel wall imaging: how we do it. Radiology 286, 12–28. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2017162096 (2018).

Cho, S. M., Park, S. Y., Kwak, H. S. & Hwang, S. B. Strong contrast stagnation of unilateral vertebral artery on Three-Dimensional black Blood-Enhanced MRI predicts acute medulla infarction. Neurointervention 18, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.5469/neuroint.2023.00017 (2023).

Wake-Buck, A. K., Gatenby, J. C. & Gore, J. C. Hemodynamic characteristics of the vertebrobasilar system analyzed using MRI-based models. PLoS One. 7, e51346. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051346 (2012).

Yu, J. et al. Relationship between the geometry patterns of vertebrobasilar artery and atherosclerosis. BMC Neurol. 18, 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-018-1084-6 (2018).

Bae, J. H. et al. Association of left vertebral artery hypoplasia with posterior circulation stroke and the functional outcome of patients with atrial Fibrillation-Related cardioembolic stroke. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 44, 65–69. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A7738 (2023).

Qiao, Y. et al. Carotid plaque neovascularization and hemorrhage detected by MR imaging are associated with recent cerebrovascular ischemic events. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 33, 755–760. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A2863 (2012).

Zhang, D. et al. Assessing the characteristics and diagnostic value of plaques for patients with acute stroke using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 12, 1529–1538. https://doi.org/10.21037/qims-21-531 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Association of morphology of lenticulostriate arteries and proximal plaque characteristics with single subcortical infarction: A Whole-Brain High-Resolution vessel wall imaging study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13, e032856. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.032856 (2024).

Yushkevich, P. A. et al. User-Guided segmentation of Multi-modality medical imaging datasets with ITK-SNAP. Neuroinformatics 17, 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12021-018-9385-x (2019).

Del Brutto, V. J. et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of intracranial Dolichoectasia in individuals with ischemic stroke. Stroke 52, 2311–2318. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032225 (2021).

Samim, M., Goldstein, A., Schindler, J. & Johnson, M. H. Multimodality imaging of vertebrobasilar Dolichoectasia: clinical presentations and imaging spectrum. Radiographics 36, 1129–1146. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2016150032 (2016).

Smoker, W. R., Price, M. J., Keyes, W. D., Corbett, J. J. & Gentry, L. R. High-resolution computed tomography of the Basilar artery: 1. Normal size and position. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 7, 55–60 (1986).

Kim, Y. N. et al. Usefulness of silent MRA for evaluation of aneurysm after Stent-Assisted coil embolization. Korean J. Radiol. 23, 246–255. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2021.0332 (2022).

Kim, C., Sohn, J. H. & Choi, H. C. Are the anomalous vertebral arteries more hypoplastic? Retrospective linear mixed model approach. BMC Neurol. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0951-x (2017).

Sarikaya, B. et al. Comparison of time-of-flight MR angiography and intracranial vessel wall MRI for luminal measurements relative to CT angiography. Br. J. Radiol. 94, 20200743. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20200743 (2021).

Xu, W. H. et al. Middle cerebral artery intraplaque hemorrhage: prevalence and clinical relevance. Ann. Neurol. 71, 195–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22626 (2012).

Yu, J. H. et al. Association of intraplaque hemorrhage and acute infarction in patients with Basilar artery plaque. Stroke 46, 2768–2772. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009412 (2015).

Gupta, A. et al. Gadolinium enhancement in intracranial atherosclerotic plaque and ischemic stroke: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5 https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.003816 (2016).

Song, J. W. et al. Vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers of symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Stroke 52, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031480 (2021).

Zheng, T. et al. Studying the imaging features and infarction mechanism of vertebrobasilar Dolichoectasia with high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Pathol. 33, e13135. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.13135 (2023).

Zhu, W. et al. Study on the correlation of vertebral artery dominance, Basilar artery curvature and posterior circulation infarction. Acta Neurol. Belg. 116, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-015-0570-5 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Effect of dominant vertebral artery angle on Basilar artery curvature and plaque. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 13, 5748–5758. https://doi.org/10.21037/qims-23-74 (2023).

Tudose, R. C., Rusu, M. C. & Hostiuc, S. The vertebral artery: A systematic review and a Meta-Analysis of the current literature. Diagnostics (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13122036 (2023).

Layegh, P., Jarahi, L., Hassannejad, E. & Arab, M. The association between vertebral artery hypoplasia and fetal-type variants of the posterior cerebral artery with imaging findings among patients with posterior circulation stroke: A single-center cross-sectional study. Health Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.1918 (2024).

Dinc, Y., Ozpar, R., Emir, B., Hakyemez, B. & Bakar, M. Vertebral artery hypoplasia as an independent risk factor of posterior circulation atherosclerosis and ischemic stroke. Medicine 100, e27280. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000027280 (2021).

He, L., Zhang, C. L., Chen, Q., Wang, L. & Huang, Y. Endothelial shear stress signal transduction and atherogenesis: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther. 235, 108152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108152 (2022).

Bakalarz, M., Rozniecki, J. J. & Stasiolek, M. Clinical characteristics of patients with vertebral artery hypoplasia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159317 (2022).

Katsanos, A. H., Kosmidou, M., Kyritsis, A. P. & Giannopoulos, S. Is vertebral artery hypoplasia a predisposing factor for posterior circulation cerebral ischemic events? A comprehensive review. Eur. Neurol. 70, 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1159/000351786 (2013).

Hong, J. M. et al. Vertebral artery dominance contributes to Basilar artery curvature and peri-vertebrobasilar junctional infarcts. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 80, 1087–1092. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2008.169805 (2009).

Thierfelder, K. M. et al. Vertebral artery hypoplasia: frequency and effect on cerebellar blood flow characteristics. Stroke 45, 1363–1368. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004188 (2014).

Yan, H. et al. Differences in intracranial atherosclerosis plaque between posterior circulation and anterior circulation on high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 33, 107616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2024.107616 (2024).

Kumar, R. K. & Balakrishnan, K. R. Influence of lumen shape and vessel geometry on plaque stresses: possible role in the increased vulnerability of a remodelled vessel and the shoulder of a plaque. Heart 91, 1459–1465. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2004.049072 (2005).

Cao, S. et al. Basilar artery curvature increases the risk of posterior circulation infarction occurrence in patients without vertebrobasilar stenosis. Neurol. Sci. 44, 1273–1280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06566-y (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Effect of Mid-Basilar artery angle and plaque characteristics on Pontine infarction in patients with Basilar artery plaque. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 30, 182–191. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.63520 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all the investigators’ contribution to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.X., X.Q. and J.W. conceived the study. J.X. and Y.L. wrote the article. J.X., L.M., Xia J. and H.C. collected and analyzed the data. J.X. performed the statistical analysis. C.Z. reviewed and edited the work for publication. X.Q. provided study supervision. J.W. received funding for the study. J.W. and X.Q. are the corresponding authors. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, J., Liu, Y., Mei, L. et al. Vessel wall imaging of vertebrobasilar artery configurations associated with posterior circulation infarction and high-risk atherosclerotic plaques. Sci Rep 15, 14780 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96729-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96729-6