Abstract

This study investigates the impact of different mechanical properties, test procedures, and environmental and economic factors on the Material Circularity Index (MCI) of rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures. Four mixtures, including new and rejuvenated mixtures with 35%, 50%, and 65% reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP), were evaluated using resilient modulus, moisture susceptibility, indirect tensile fatigue, semi-circular bending, and dynamic creep tests. A novel definition of MCI was introduced, integrating cost, CO2 emissions, and mechanical properties. Results indicate that the 50% RAP mixture consistently performed best across a range of scenarios, especially in varying climates and when multiple performance criteria were considered, with an MCI ranging from 0.38 to 0.83. Meanwhile, the 65% RAP mixture was optimal when cost and environmental considerations were prioritized, particularly in moderate to low temperatures. The findings also imply the importance of selecting appropriate performance parameters and test methods, as the choice of dynamic creep test procedures was shown to significantly influence MCI values. Ultimately, this study demonstrates that the MCI can serve as a multi-conceptual index for selecting appropriate asphalt mixtures. This process ensures a sustainable, performance-based asphalt mixture selection by integrating regional conditions, performance needs, and environmental factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recycled asphalt mixtures are increasingly used in pavement construction due to their environmental and economic benefits. The use of recycled asphalt mixtures serves as an effective and sustainable alternative to conventional asphalt mixtures1. Environmental advantages include reducing landfill usage, conserving nonrenewable materials such as bitumen and aggregates, and lowering greenhouse gas emissions2,3,4,5. Moreover, the overall cost of asphalt mixtures is reduced through decreased production costs, reduced consumption of raw materials, and minimized landfill expenses5,6,7. However, concerns regarding the low-temperature and fatigue performance of recycled asphalt mixtures have limited their broader adoption. Studies have shown that using high percentages of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) can lead to increased mixture stiffness and reduced phase angles8,9. Consequently, rejuvenators are employed to restore the properties of RAP materials, particularly in high RAP content mixtures10.

Numerous studies have been conducted to evaluate the performance of rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures. Bilema et al.11 investigated recycled asphalt mixtures containing 25% and 40% RAP and observed that the use of a rejuvenator led to an increase in permanent deformation and rut depth. This effect was attributed to the reduction in stiffness of the recycled asphalt mixtures due to the presence of the rejuvenator. Additionally, they reported an improvement in moisture susceptibility resistance, which was attributed to enhanced cohesion between bitumen and aggregate, as well as improved adhesion between aged and virgin bitumen. In another study, Zhang et al.12 investigated the fatigue, rutting, and moisture susceptibility of high-percentage recycled asphalt mixtures. They reported that using a rejuvenator increased the fatigue life of the mixture, although it also led to increased moisture susceptibility and permanent deformation. Moniri et al.13 examined the effects of two different rejuvenators on recycled asphalt mixtures containing 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% RAP. They concluded that the use of rejuvenators effectively improved the intermediate and low-temperature performance of the mixtures, though it also increased the rutting potential by reducing the flow number value. Other researchers have also concurred on the positive impact of rejuvenators on the fatigue and low-temperature performance of recycled asphalt mixtures, as well as the negative impact on rutting resistance14,15,16,17,18,19,20. A review of previous studies indicates that the presence of a rejuvenator reduces the stiffness of aged bitumen and RAP materials, leading to a decrease in the overall stiffness of the final rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures10,11,12,13. Consequently, the low-temperature properties of the mixtures are enhanced due to the improved flexibility. However, this reduction in stiffness negatively affects the rutting resistance and resilient modulus of the asphalt mixtures11,12,13. Additionally, the softening of the asphalt mixture, combined with a reduction in the phase angle of the recycled asphalt mixture, contributes to an improvement in the fatigue performance of the asphalt mixture10,11,13. Therefore, it is crucial to establish a balance between the various mechanical performance aspects of recycled asphalt mixtures to ensure optimal overall performance.

The circular economy is a framework designed to minimize waste and maximize resource efficiency. In this model, products, materials, and resources are reused, refurbished, or recycled rather than discarded, spanning various stages such as production, distribution, and consumption21,22. Several tools exist to quantify the sustainability impacts of products, including Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Environmental Sustainability and Circularity Index (ESCI), Biogenic Carbon Storage (BCS), and Material Circularity Index (MCI), among others. LCA is used to evaluate the environmental impacts of products or processes across their entire life cycle23. It helps identify areas for sustainability improvement by quantifying energy consumption, waste generation, emissions, and resource use24. ESCI measures the sustainability and circularity of a system or product, incorporating environmental impacts weighted by the level of circularity25. Additionally, BCS refers to the capture and storage of carbon through biological processes, such as the biogenic carbon sequestered within individual products, and it is not included in the lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions removals26.

One of the effective tools which can be employed to investigate the circularity level of products (recycled asphalt mixtures in this study), is the material circularity index (MCI). This tool considers the different performance of the asphalt mixture together and at the same time, compares the performance of the recycled asphalt mixture to the original asphalt mixture based on the mechanical properties26,27,28,29,30,31. Corona et al.26 used the MCI to evaluate the performance of lignin-based asphalt. They considered service life and permanent deformation as the parameters for assessing asphalt mixture performance. Their findings indicated that the MCI of lignin-based asphalt roads was slightly higher than that of bitumen-based asphalt roads. The observed effects may be attributed to the lower biobased mass in the lignin-based scenarios. In addition, Maltalovas and Di Mino28 studied the performance of recycled asphalt mixtures in different layers of road pavement using the MCI. They considered permanent deformation and service life as performance parameters for evaluating MCI and found that recycled asphalt mixtures achieved the highest MCI value when used in the base course. In another study, Maltalovas and Di Mino29 evaluated the combined effects of permanent deformation and fatigue performance of recycled asphalt mixtures containing 30%, 60%, and 90% RAP using the MCI. The results showed that recycled asphalt mixtures with 60% and 90% RAP had similar MCI values, both higher than other mixtures, indicating a more favorable performance based on the MCI approach.

If economic and environmental analyses demonstrate the desirability of using RAP, rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures serve as an alternative to original asphalt mixtures for road construction. However, the mechanical properties of these mixtures vary, necessitating an appropriate evaluation tool to assess their performance comprehensively. The MCI has recently gained popularity for evaluating various aspects of asphalt mixture performance. Despite the introduction of MCI for assessing the influence of mechanical properties in the selection of asphalt mixtures, prior studies have primarily utilized this index by considering only two or three performance parameters. Additionally, the impact of various performance indices and different experimental test procedures on MCI outcomes has not been addressed in previous research works. Furthermore, cost and CO2 emissions were not incorporated as factors in the MCI evaluation in the previous studies. In this study, the influence of including various combinations of performance properties—such as permanent deformation (using an index from three different test setups), fatigue performance, low-temperature properties, moisture susceptibility, resilient modulus, cost, and environmental impact—on the MCI value has been investigated. This approach is crucial for comprehensively determining the MCI in the comparison of different types of recycled asphalt mixtures and highlights the importance of selecting appropriate performance parameters to identify the most suitable mixture type. The objectives of this study are twofold: first, to assess the impact of various combinations of mechanical properties, cost, and CO2 emissions on the Material Circularity Index (MCI); and second, to examine the influence of different testing procedures for similar mechanical properties on the MCI.

Unlike previous studies, which applied the MCI within limited and controlled scenarios featuring a narrow range of asphalt mixture properties, this research broadens its application to a more diverse set of conditions. In other words, prior studies typically incorporated only two or three performance properties of asphalt mixtures in the utility factor for MCI calculation, without explicitly clarifying the rationale behind selecting these properties. This study identifies multiple utility factors encompassing various performance properties while considering aspects such as practical applicability and regional climate conditions. This approach allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of different scenarios on MCI values. Therefore, the novelty of this study lies in evaluating the effectiveness of the MCI as a selection tool for identifying the most suitable asphalt mixture under varying conditions. Additionally, this study explores the influence of different test methods on MCI outcomes, an aspect that has not been previously investigated. Furthermore, incorporating cost and CO2 emissions into the MCI calculation represents a key innovation, as earlier studies rarely accounted for factors beyond performance properties in utility factor evaluations.

Theoretical basis

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation developed a framework to assess product circularity using a tool called the Material Circularity Index (MCI)30. MCI is a methodological framework developed to assess the circularity of recycled asphalt mixtures by systematically integrating environmental impact metrics (e.g., resource efficiency, waste reduction) and mechanical performance criteria (e.g., rutting resistance, fatigue life, moisture susceptibility)26,27,28,29,30,31. The MCI quantifies the alignment of recycled materials with circular economy principles while evaluating their performance against conventional asphalt mixtures. This framework ensures recycled mixtures achieve resource efficiency and meet engineering performance standards, addressing potential trade-offs between sustainability and structural integrity. The MCI is measured on a scale from 0 to 1, where a value of 1 represents a fully circular product, indicating optimal performance in terms of material reuse and recycling. In contrast, an MCI of 0.1 indicates a product that meets basic industry standards but remains suboptimal, while an MCI of 0 signifies a product that falls below acceptable industry thresholds and demonstrates poor circularity performance31. The MCI is mathematically represented by Eq. (1):

where, the MCI* is calculated using Eq. (2)31.

in which, the Linear Flow Index (LFI) and the Utility Factor (X) are key components, determined by Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively31.

In these equations, the variables V, W, M, WF, and WC denote the mass of virgin feedstock, the mass of unrecoverable waste material, the total mass of production, the mass of waste produced during the generation of recycled content, and the mass of waste generated during the recycling process, respectively. These variables are computed through Eq. (5) to (8). Additionally, Pi in Eq. (4) represents the desired properties of the product, with mechanical performance being the primary focus in this study31.

In these equations, PRA refers to the percentage of RAP in the recycled asphalt mixture, FRA represents the percentage of recycled material at the end of its life cycle, EF signifies the efficiency of the recycling process during production, and EC refers to the efficiency of the recycling process during treatment. Furthermore, the total mass of waste material sent to the landfill, denoted as WEOL, is computed using Eq. (9)31.

Given that the efficiency of the recycling process during both production and treatment is assumed to be 100%, and that no recycling of the asphalt mixture occurs at the end of its service life (i.e., FRA = 0) for all mixtures analyzed in this study, the MCI* can be simplified. The simplified form is presented in Eq. (10)31.

Furthermore, the researchers incorporated the effects of cost and environmental considerations into the MCI as a utility factor. In this study, the modified Material Circularity Index, denoted as MCIME, was introduced and calculated to include mechanical, economic, and environmental impacts. It is important to note that the equation for MCIME remains the same as that of the original MCI*. However, in the MCIME calculation, the utility factor is expanded to include cost and environmental components, which are treated as critical parameters alongside the mechanical properties. This holistic approach ensures a more comprehensive evaluation of the recycled asphalt mixtures, taking into account not only their performance but also their economic viability and environmental sustainability.

Methodology

In this section, the properties of the materials utilized in this study are presented. Additionally, the test methods employed in this research, including different types of dynamic creep tests, resilient modulus test, semi-circular bending test, moisture susceptibility test, and indirect tensile fatigue test, are discussed. Finally, the procedures for producing artificial RAP, selecting the appropriate rejuvenator content, and preparing samples for all the experiments considered in this study are described.

Materials

Bitumen

The bitumen used in this study had a performance grade (PG) of 64-22. Table 1 outlines the properties of this bitumen, which was acquired from the Pasargad oil company.

Aggregate

The physical properties of the limestone aggregate used in this study are described in Table 2. The aggregate gradation employed for producing the asphalt mixture is illustrated in Fig. 1. The proposed gradation falls appropriately within the specified lower and upper limits defined by ASTM D44838. Notably, the nominal maximum aggregate size (NMAS) used in this study was 19 mm.

Rejuvenator

Table 3 presents the properties of the Triglyceride/Fatty Acid rejuvenator used in this study to restore the chemical and rheological properties of the aged bitumen.

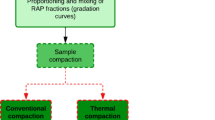

Sample preparation

In this section, the production processes of Laboratory RAP, identification of rejuvenator content, and production of reclaimed asphalt mixtures were explained. The Marshall mix design for medium traffic, using 50 blows of the Marshall hammer, was employed to determine the optimal bitumen content for the asphalt mixtures following the MS-2 guideline44. Following this procedure, the optimum bitumen content was determined to be 5.65% by total weight of the mixture. It is noteworthy that laboratory-produced RAP, derived from the same mix design, was utilized in this study. To ensure methodological consistency and eliminate variability introduced by differing mix designs, all mixtures -including both new and recycled asphalt formulations- were produced using the standardized mix design. This approach assumes full participation of the aged bitumen in the recycled mixtures. The volumetric properties of the mix design were validated and are summarized in Table 4.

In this study, laboratory RAP was utilized to produce recycled asphalt mixtures, enabling precise control over experimental conditions and variables. Various methods exist for producing laboratory RAP45; however, in this study, laboratory RAP was manufactured following the NCHRP 973 guidelines developed by Kim et al.46. According to recent findings reported by Gholami et al.47, the 5-day aging duration prescribed by this protocol results in an aging level comparable to one cycle of PAV aging, equivalent to approximately 10 years of field-aged RAP, with aging beyond 5 days showing no significant impact on the properties of the bitumen. To achieve short-term aging, the loose asphalt mixture was spread in a 4 cm deep pan and placed in an oven at 135 °C for 4 h, with stirring every hour. For long-term aging, the mixture from the previous step was transferred to an oven at 95 °C for 5 days, with daily stirring to ensure uniform aging.

Rejuvenator content

Following the production of laboratory RAP, the bitumen was extracted from the laboratory RAP mixtures following the ASTM D217248 standard, which involves separating the aged bitumen from the aggregate using trichloroethylene as the solvent. After the extraction process, the solvent was removed from the bitumen using a Buchi rotary evaporator, in accordance with ASTM D540449.

The optimal percentage of rejuvenators is the amount that, when added to recycled asphalt mixtures, improves their stiffness and cracking resistance without compromising rutting resistance. Several methods are available to determine the optimal rejuvenator content. One approach involves the use of penetration and softening point tests50, while performance tests for bitumen51,52,53,54,55 offer another method. In the first approach, the optimal rejuvenator percentage is determined by restoring the penetration of the blended bitumen (a combination of fresh and aged bitumen). The softening point at the calculated rejuvenator percentage should fall within the acceptable range for fresh bitumen. Additional tests, such as viscosity and rheological properties, may be conducted if necessary50.

In the second method, the optimal rejuvenator percentage is determined through functional performance tests, which can be done in three ways: (1) restoring the lower performance grade (PGL) while controlling the higher performance grade (PGH), (2) achieving a ΔTc value of − 5 °C, or (3) restoring PGH51.

Aligned with previous research findings, restoring the PGH value has proven to be an effective method for determining the optimum rejuvenator content51,53. Therefore, in this study, this method was employed to identify the optimal rejuvenator dosage for each type of recycled asphalt mixture. For this purpose, the aged bitumen extracted from RAP was initially blended with three different rejuvenator percentages—5%, 6%, and 7% by weight of the aged bitumen. Following this, neat bitumen was added to the mixture according to the mix design for each type of recycled asphalt mixture. This approach for producing the blended bitumen was considered optimal for identifying the rejuvenator content, based on the rutting and fatigue performance results, as supported by the findings of Ma et al.56. Ultimately, the rejuvenator content was selected to achieve a PGH value similar to that of the neat bitumen. This adjustment resulted in rejuvenator dosages of 2.345%, 2.85%, and 3.77% by weight of bitumen in the total mixtures, equivalent to 6.7%, 5.7%, and 5.8% by weight of aged bitumen, for recycled asphalt mixtures containing 35%, 50%, and 65% RAP, respectively. This indicates that the rejuvenator dosage required for 1000 kg mixtures with 35%, 50%, and 65% RAP was calculated to be 1.38 kg, 1.61 kg, and 2.13 kg, respectively.

Producing recycled asphalt mixture

To evaluate the performance of the rejuvenator and the effectiveness of recycled asphalt mixtures at lower RAP percentages, a 35% RAP content was considered in this study. This selection is based on the fact that pavements containing less than 30% RAP typically do not require rejuvenators to restore their properties. Given the significance of 50% RAP content and its widespread application in construction projects, this percentage was also considered. Moreover, the RAP content in recycled hot mix asphalt is generally capped at 50% in conventional batch plants due to limitations in heat capacity and concerns regarding carbon emissions. The inclusion of 65% RAP content in this study is justified by the capability of drum mix plants to accommodate higher RAP levels, allowing for RAP proportions between 60% and 70%. Additionally, the maximum practical utilization of RAP in pavements is typically below 70%57. Therefore, three distinct rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures were produced in this study, incorporating RAP contents of 35%, 50%, and 65%, respectively.

The RAP content was initially combined with the optimal rejuvenator dosage. Subsequently, new bitumen and aggregate were added to the RAP and rejuvenator blend according to the mix design, and the mixture was thoroughly combined. This process resulted in the production of rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures. The same procedure was followed for recycled asphalt mixtures containing other RAP content.

Test methods

To assess the performance of rejuvenated asphalt mixture, different types of dynamic creep tests, resilient modulus test, moisture susceptibility test, indirect tensile fatigue test, and semi-circular bending test were performed which are outlined as follows:

Dynamic creep test

In this section, three different procedures for conducting the dynamic creep test were presented, as outlined in AASHTO T37858, BS-EN 12697-2559, and AS2891-12-152. These standards were employed to evaluate the permanent deformation behavior of the asphalt mixtures, providing a comprehensive comparison of test methods used in different regions and contexts.

AASHTO T378 test method

This test was conducted on cylindrical specimens with dimensions of 100 mm in diameter and 150 mm in height in accordance with AASHTO T37858. three standard samples were prepared by producing an asphalt mixture slab with a 7% air void content, and 100 mm cores were extracted from it. During the test, a repeated haversine axial compressive stress with a frequency of 1 Hz was applied, consisting of a cyclic stress of 600 kPa for 0.1 s and a contact stress of 30 kPa for the remaining 0.9 s using a UTM25-IPC device. The test was performed at a temperature of 50 °C, and measurements of the cycle and permanent deformation were recorded.

BS-EN 12697-25 test method

The dynamic creep test was conducted on cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 150 mm and a height of 60 mm, as specified in the BS-EN 12697-25 standard test method59. Gyratory compacted specimens, also 150 mm in diameter, were prepared with an air void content of 4%. Three samples of the required dimensions were extracted from these gyratory specimens for testing. A loading platen with a diameter of 100 mm was used to apply compressive stress to the confined sample, facilitating the evaluation of rutting resistance. In this procedure, a rectangular compressive cyclic stress of 100 kPa was applied for 1 s, followed by a contact stress of 15 kPa for 1 s, resulting in a cycle time of 2 s using a UTM25-IPC device. The test temperature was maintained at 50 °C, and permanent deformation was recorded after each cycle.

AS2891.12.1 test method

This test method utilized cylindrical specimens with an air void content of 7%, measuring 100 mm in diameter and 75 mm in height52. To prepare three required samples, asphalt mixture slabs were first produced using a Pres.Box, and the cylindrical specimens were then extracted by coring the slabs with a core drill. The loading protocol involved the application of a haversine cyclic compressive stress of 400 kPa for 0.5 s, followed by a contact stress of 20 kPa during a 1.5-second rest period, resulting in a total cycle duration of 2 s52 using a UTM25-IPC device. The test was conducted at a controlled temperature of 50 °C, and the permanent deformation was measured after each loading cycle.

Flow number calculation

In the AASHTO T378 standard, the Flow Number (FN) obtained from the dynamic creep test results is used to assess the asphalt mixture’s resistance to rutting. The flow number represents the cycle at which the permanent strain rate reaches its minimum value. An approach recommended by Arizona State University was used to calculate the flow number for each type of asphalt mixture, which involves fitting the Francken model to the curve of permanent strain versus load cycle. The fitted model is shown in Eq. (11).

Where: ɛp and n represent the permanent axial strain and the number of cycles, respectively, while A, B, C, and D are the fitting coefficients. The flow number (FN) is calculated as the cycle at which the second derivative of the permanent strain with respect to the number of cycles becomes zero.

Moisture susceptibility test

In this test, conducted in accordance with AASHTO T28360, six cylindrical specimens were cored from an asphalt mixture slab with a 7% air void content. The diameter and height of each specimen were 100 mm and 63.5 mm, respectively. Half of the specimens were conditioned prior to testing. These samples were partially saturated in water until the degree of saturation reached between 55% and 80%. The saturated specimens were then sealed in plastic bags containing 10 mL of water and placed in a freezer at − 18 °C for 16 h. Following this, the samples were removed from the plastic bags and placed in a water bath at 60 °C for 24 h. Finally, the samples were transferred to a water bath at 25 °C for 2 h.

A displacement-controlled test was conducted on both dry and conditioned samples at a rate of 50 mm/min at 25 °C using a UTM25-IPC device. For each specimen, the maximum load was recorded. The tensile stress ratio (TSR) was defined as the ratio of the average tensile strength of the conditioned specimens to the average tensile strength of the dry specimens.

Resilient modulus test

This test was performed following ASTM D736961. To prepare the samples, asphalt mixture slabs with an air void content of 4% were produced, from which three cylindrical samples with a diameter of 100 mm and a height of 63.5 mm were cored. The test was performed at a temperature of 25 °C, applying an indirect haversine tensile load with an amplitude of 1000 N by rotating the samples 90° under the UTM device, with no rest period during the test. After 100 pre-loading cycles, the average of the subsequent five resilient modulus measurements was recorded as the resilient modulus value.

Indirect tensile fatigue (IDT-Fatigue) test

This test was conducted on cylindrical samples with a diameter of 100 mm and a height of 63.5 mm. The sample preparation was consistent with that used for the resilient modulus test, and the test temperature was maintained at 25 °C. For each type of asphalt mixture, three different stress levels—250, 350, and 450 kPa—were applied using a UTM25-IPC device, resulting in nine samples for each asphalt mixture. The loading was a haversine type with a frequency of 2 Hz, consisting of a 0.1-second cyclic stress followed by a 0.4-second contact stress. The test procedures were detailed in the BS EN 12697-2462 standard. The cycle count, deformation, and strain were recorded until the sample failed or the device reached its operational limits.

Using the stress value, permanent horizontal deformation, sample diameter, and Poisson’s ratio, the horizontal strain and stiffness modulus of the mixtures were calculated through Eqs. (12) and (13), respectively.

where, ΔH represents the horizontal deformation (mm), D is the sample diameter (mm), σ refers to the horizontal tensile stress at the center of the specimen (MPa), ε denotes the horizontal strain (µm/m), ν is the Poisson’s ratio, and Smix is the stiffness modulus (MPa). The stiffness modulus Smix values were calculated using Eq. (13) for all test results. In the previous studies, different methods were used to compare the fatigue life of asphalt mixtures63. One of the accepted methods used in this study defines the fatigue failure criterion as the cycle at which the maximum value of the product of stiffness modulus and the number of cycles (Smix×cycle) is achieved63,64. The fatigue life determined using this method, established in ASTM D746065 and based on the dissipated energy theory, is denoted as NfNM.

Semi-circular bending (SCB) test

In this test, cylindrical samples were produced using gyratory compaction to achieve an air void content of 4%. The cylindrical specimens were then cut to a thickness of 25 mm and halved to create two semi-cylindrical specimens, each with a diameter of 150 mm and a thickness of 25 mm. For each asphalt mixture type at each temperature, three semi-cylindrical specimens were utilized, resulting in a total of six specimens per mixture type. These specimens were used to determine fracture energy (Gf), stiffness (S), and fracture toughness (KIC) following AASHTO TP10566. A notch with a length of 15 mm and a width of 1.5 mm was introduced along the axis of symmetry in each specimen. The test was performed on each type of asphalt at two temperatures, − 12 °C and − 24 °C, using displacement-controlled loading at a load line displacement rate of 0.05 mm/min using a UTM25-IPC device. Throughout the test, both load and displacement values were recorded.

Several approaches outlined in the AASHTO TP10566 manual are available to assess the low-temperature performance of asphalt mixtures using SCB test results. These include evaluating fracture energy (Gf), fracture toughness (KIC), and stiffness (S)66. This study focused on KIC (which indicates the material’s resistance to crack propagation) to assess the low-temperature performance of the asphalt mixture. AASHTO TP10566 provides Eq. (14) for calculating the value of KIC.

Where, P represents the applied load (MN), r is the specimen radius (m), t is the specimen thickness (m), and a denotes the notch length (m).

Results and discussions

In this section, the mechanical properties of the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures are first presented. Following that, the influence of considering various performance properties on the Material Circularity Index (MCI) is analyzed and discussed. This study does not undertake a comprehensive analysis of the specific factors influencing the performance outcomes observed in the asphalt mixtures. Instead, it emphasizes presenting these results to establish a foundation for calculating the MCI.

Mechanical properties

Dynamic creep test results

The results of the dynamic creep test and the flow number values obtained for each type of rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture are presented in Fig. 2. As shown, the flow number values varied with different percentages of RAP, each adjusted with the rejuvenator content determined using the PGH method. Despite identifying the rejuvenator content based on the rutting performance of the bitumen (following Superpave specifications), the rutting performance at the mixture scale exhibited variability. This indicates that the most realistic approach for determining the optimal rejuvenator content is through performance tests conducted at the mixture level. It was observed that for higher percentages of RAP in the recycled asphalt mixture, determining the rejuvenator content based on bitumen properties did not align with the performance outcomes observed in the full mixtures. This suggests that as the RAP content increases, the rejuvenator content determined using traditional methods may not fully restore the desired performance characteristics, highlighting the need for alternative approaches or adjustments when dealing with higher RAP levels.

Furthermore, the results demonstrate that all mixtures met the flow number requirements for medium traffic conditions. Specifically, mixtures containing up to 65% RAP passed the requirement for up to 10 million ESALs, while the other mixtures were suitable for up to 30 million ESALs, in accordance with AASHTO T37858.

On the other hand, the flow number results obtained from the BS EN 12697-25 and AS 2891.12.1 test methods for all recycled asphalt mixtures are presented in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. As shown, the performance of the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures, in terms of flow number, varied between the two testing methods, both of which differed with the AASHTO T378 test method. This indicates that the trend in rutting performance assessment may differ depending on the test method used. Therefore, it can be concluded that using different test procedures may yield inconsistent trends in evaluating the rutting performance of rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures.

Various parameters can influence the observed trends and may lead to variations in the flow number values obtained from different test procedures. One potential reason for these discrepancies is that the selection of the optimal rejuvenator content was based on restoring the high PG of the blended bitumen, which consists of aged bitumen, neat bitumen, and rejuvenator. It appears that the chosen rejuvenator content affects the performance of the mixtures at the mixture scale in distinct ways. Analysis of the dynamic creep properties indicates that the rejuvenator dosage used for mixtures with varying percentages of RAP may have been either higher or lower than the required level, resulting in differing trends in the rutting performance and flow number of recycled asphalt mixtures. Additionally, variations in testing conditions, such as loading and resting times, the magnitude of applied loads, and particularly the dimensions of test specimens across different test procedures, could contribute to the observed variations in results. These factors underscore the importance of carefully considering testing protocols and parameters when interpreting experimental outcomes and thus, special attention should be given to the deformation and recovery behavior of materials with varying stiffness levels, as these properties can significantly influence the rutting performance observed in different tests.

Moisture susceptibility test results

As mentioned previously, the moisture susceptibility of the mixtures was evaluated using the Tensile Strength Ratio (TSR), determined in accordance with AASHTO T28360. A higher TSR value indicates that the impact of wet conditioning on the indirect tensile stress results was minimal. Previous research has shown that incorporating RAP into asphalt mixtures can enhance resistance to moisture susceptibility12,67,68. However, the use of rejuvenators in recycled asphalt mixtures has often been found to increase moisture susceptibility, leading to a reduction in TSR values13,69,70. Additionally, an acceptable TSR value for asphalt mixtures is generally above 80% in most standards, although some agencies also accept a TSR value above 70% according to local experience44.

Considering the results presented in Fig. 5, it is evident that the TSR values of the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures fall within the acceptable range. As observed, the asphalt mixture containing 35% RAP exhibited a lower TSR percentage compared to the original asphalt mixture, whereas the other rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures demonstrated better moisture susceptibility performance than the new mixtures. This difference may be attributed to the lower percentage of RAP and the relatively higher percentage of rejuvenator (to the RAP weight in the mix), which could have increased the moisture susceptibility of the 35% RAP mixture compared to the others in this study. As demonstrated in previous studies, the reduction in moisture susceptibility observed in recycled asphalt mixtures can be attributed to enhanced cohesion between the bitumen and aggregate, as well as improved adhesion between aged and virgin bitumen11,13. However, the use of rejuvenators has been shown to weaken the layered structure of recycled asphalt mixtures due to the increased participation of aged bitumen in the mixtures13.

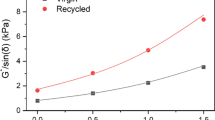

Resilient modulus test results

Figure 6 presents the results of the resilient modulus for all asphalt mixtures in this study. The data indicates that the resilient modulus of the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures increased in comparison to the original asphalt mixture. This improvement in resilient modulus suggests that, if traditional pavement design methods such as the AASHTO 199371 guideline are applied, the increased stiffness of the recycled mixtures could lead to a reduction in the required pavement layer thickness. The resilient modulus plays a key role in determining the required pavement layer thickness. In these methods, the pavement thickness is designed to distribute the loads over the subgrade, minimizing deformation and prolonging pavement life.

The incorporation of RAP in asphalt mixtures leads to an increase in the resilient modulus, primarily due to the higher stiffness of the final mixtures. However, the presence of a rejuvenator in recycled asphalt mixtures reduces the stiffness contributed by the RAP materials10,11,12,13. As it is represented in Fig. 6, the resilient modulus of rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures is slightly higher than that of original asphalt mixtures, indicating that the stiffening effect of the RAP material overcomes the influence of the rejuvenator. Furthermore, the mixture containing 50% RAP exhibits the highest resilient modulus, which may be attributed to the relatively lower rejuvenator content (by weight of RAP) compared to mixtures with other RAP percentages.

Indirect tensile fatigue (IDT-Fatigue) test

Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between Smix and the number of cycles for the rejuvenated asphalt mixtures. The values of NfNM as a function of the stress level for all rejuvenated mixtures are also presented in Fig. 7, commonly referred to as the Wöhler diagram. The results indicate that using a rejuvenator can enhance the fatigue performance of recycled asphalt mixtures. However, its effectiveness diminishes at higher stress levels compared to lower ones. Additionally, the slope of the Wöhler diagram increases with the rise in RAP content, which is an expected outcome.

Consistent with previous studies, the use of RAP materials in asphalt mixtures increases the stiffness of the final mixtures due to the presence of aged bitumen. This elevated stiffness has a detrimental effect on the intermediate performance, particularly the fatigue resistance, of the mixtures. Additionally, restoring the phase angle of the aged bitumen in RAP is a critical factor in enhancing the fatigue performance of recycled asphalt mixtures. Both of these issues were addressed through the use of a rejuvenator10,11,13. Since the rejuvenator content in this study appears to exceed the necessary amount for improving rutting performance, it is probable that mixtures with a high percentage of RAP exhibit slightly better or comparable fatigue performance relative to new mixtures, as evidenced by the results of this study. Additionally, at lower stress levels, mixtures with higher RAP content exhibited improved fatigue resistance compared to the control mixture. This enhancement can be attributed to the increased stiffness provided by the aged bitumen in the RAP, which is advantageous under low-stress conditions. However, at higher stress levels, the trend reversed, likely due to the increased brittleness and reduced flexibility of the mixtures with higher RAP content, making them more susceptible to cracking under elevated stress.

Semi-circular bending (SCB) test results

Figure 8 presents the value of KIC calculated for all rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures at two temperatures of − 12 °C and − 24 °C. As observed, the addition of the rejuvenator resulted in KIC values that were comparable to those of original asphalt mixtures. However, an increase in the percentage of RAP correspondingly led to a reduction in the KIC value, indicating that the RAP content shows a more significant influence than the rejuvenator content on the low-temperature performance of the asphalt mixtures. In addition, a decrease in temperature led to an increase in the KIC value72. However, when the temperature drops significantly, the KIC value may diminish due to the occurrence of brittle failure and the increased presence of microcracks73, as observed in this study.

As illustrated in Fig. 8, the fracture toughness (KIC) of rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures at − 12 °C was higher than that at − 24 °C. This observation aligns with the expected behavior of asphalt mixtures at lower temperatures, where the material becomes more brittle and less capable of resisting crack propagation. Additionally, the mixture containing 50% RAP demonstrated higher fracture toughness compared to mixtures with other RAP percentages, likely due to its relatively lower rejuvenator content (by weight of RAP). The observed reverse trend in fracture toughness between − 12 °C and − 24 °C can be attributed to the temperature-dependent behavior of asphalt mixtures, particularly the interaction between the aged binder in RAP and the virgin binder. At − 12 °C, the increased RAP content introduces stiffer and more brittle aged binder, reducing the mixture’s ability to resist crack initiation and resulting in lower fracture toughness. Conversely, at − 24 °C, the extreme cold causes the entire mixture to become highly stiff, and the aged binder in RAP may provide a stabilizing effect, improving stress distribution and leading to higher fracture toughness with increased RAP content.

Material circularity index (MCI)

In this section, various alternatives were analyzed, and the MCI values were calculated using both MCI* and MCIME approaches. The performance of different rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures was evaluated based on these indices. MCI* focused on mechanical properties, while MCIME incorporated additional factors such as cost and environmental impact, providing a more comprehensive assessment. This dual evaluation allowed for a thorough comparison of the mechanical, economic, and environmental performance of the mixtures under different conditions and criteria.

To calculate the value of MCI for both MCI* and MCIME approaches, all parameters were kept the same except for the utility factor. The parameters were calculated using Eq. (3) to (9), as outlined in the Sect. 2. The calculated values are presented in Table 5. It should be noted that all calculations were performed for 1,000 kg of each asphalt mixture.

Calculation of MCI*

As previously discussed, the utility factor in the MCI* formula includes mechanical properties such as permanent deformation, fatigue behavior, moisture susceptibility, resilient modulus, and low-temperature performance. In this section, a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of selecting the necessary desired properties on the MCI* value is presented. The desired properties (Pi) are given in Eqs. (15) to (19).

In these equations, the parameters P(PDi), P(NfNM), P(Mr), P(TSR), and P(KIC) represent the ratios of flow number, fatigue life, resilient modulus, moisture susceptibility, and fracture toughness of each rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture relative to the control mixture, respectively. These ratios provide a comparison between the performance of recycled mixtures and the conventional asphalt mixture used as a baseline, helping to quantify the effectiveness of the rejuvenated mixtures in the MCI framework. The Pi values were calculated using Eqs. (15) to (19), which represents the fraction of each performance property relative to the control mixtures and presented in Table 6 for further analysis. As evidenced by the data presented in Table 6, the desired properties (Pi) values of the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures are influenced by RAP content and rejuvenator dosage, as discussed in Sect. 4.1 for each mechanical and durability performance.

Different alternatives can be considered based on the specific conditions or objectives of using the mixtures. Additionally, employing different testing procedures for the same test, such as the dynamic creep test in this study, may yield varying results. To address these issues, various scenarios were developed to reflect real-world situations or challenges. These scenarios are outlined in Table 7, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of how changes in performance criteria or test methods can affect the overall evaluation of rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures. This approach helps ensure the selection of mixtures best suited to their intended use while accounting for variations in testing outcomes. In Table 7, a binary system was applied in the table, where a value of 0 indicates that a given performance index was not included as part of the scenario’s evaluation criteria. In contrast, a value of 1 signifies that the performance index was considered. The utility factor for each scenario was calculated as the final product of all desired properties (Pi), where the binary weighting factor for these properties (as specified in Table 7) was assigned a value of one for each asphalt mixture. Following the methodology outlined earlier, the MCI was derived from the calculated utility factor for each mixture type. By comparing the resultant MCI values across scenarios and identifying the maximum MCI value under each set of conditions, the optimal mixture for the corresponding scenario was systematically identified.

By applying Eqs. (1), (2), (4), and (10), the utility factor (X), MCI*, and MCIME values were calculated and are summarized in Table 8. The first three scenarios were designed to assess the effect of different test procedures on the MCI values. The results reveal that using different procedures to evaluate rutting performance leads to varying outcomes. Specifically, when employing the BS EN 12697-25 test method for dynamic creep testing, the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture with 65% RAP exhibited the highest MCI. However, in the other two methods, the mixture containing 50% RAP demonstrated superior performance. This indicates that the choice of test procedure can significantly influence the perceived performance of recycled asphalt mixtures.

Scenarios 5 to 12 were designed for regions with hot climates, which may or may not experience intermediate and low temperatures. Half of these scenarios were also used to assess the durability performance of the mixtures in these regions. The results showed that in all cases, the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture containing 50% RAP exhibited the best performance and the highest MCI, making it the most suitable option for these regions. On the other hand, the mixture with 65% RAP performed the worst in scenarios where high-temperature performance (or a combination of high, intermediate, and low-temperature performance) was critical. Additionally, the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture with 35% RAP emerged as the second-best option, demonstrating higher favorability compared to both the original asphalt mixture and the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture containing 65% RAP. These findings underscore the importance of selecting the appropriate mixture composition based on the specific environmental conditions and performance requirements.

Scenarios 13 to 16 were developed for regions with intermediate climates, which may or may not experience low temperatures and where durability performance may or may not be a key consideration. The results were consistent with those observed in hot climates, where the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture containing 50% RAP remained the optimal choice. However, in intermediate climates, the favorability of using the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture containing 65% RAP significantly increased, though it still lagged behind the 35% RAP mixture in terms of overall performance. This highlights that, while the 50% RAP mixture consistently performed best across both climate conditions, the 65% RAP mixture became more viable in regions with less extreme temperature fluctuations.

Scenarios 17 to 20 were designed to focus on the low-temperature performance of asphalt mixtures. The fracture toughness, KIC, was calculated for all mixtures at two temperatures: − 12 °C and − 24 °C. To assess the influence of lower temperatures on MCI values, the MCI was examined for both temperature conditions, revealing no significant differences in the results. When low-temperature properties were considered, with or without durability performance, the mixture containing 65% RAP showed the highest MCI value, followed by the mixture with 50% RAP as the second most favorable. As noted in the low-temperature properties analysis, the selection of optimal rejuvenator content (guided by achieving a restored high PG in the blended bitumen) may result in rejuvenator dosages exceeding the ideal threshold in mixtures with high RAP content. This surplus rejuvenator likely enhances the low-temperature performance of these mixtures. Furthermore, the MCI inherently prioritizes the use of recycled materials as a positive criterion in material selection. Consequently, the improved low-temperature properties of mixtures with high RAP content are amplified, making them more suitable for colder climatic conditions.

Additionally, the scenarios 21 and 22 examined the favorability of each mixture concerning pavement thickness, using the AASHTO 199371 method, where the resilient modulus was the primary factor. These results reinforced the suitability of the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures containing 65% RAP as the best choice, with the 50% RAP mixture closely following as a favorable option.

Finally, in Scenario 4, the combination of all mechanical performance parameters was assessed. The results demonstrated the favorability of the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures containing 50% RAP compared to the other mixtures. In conclusion, although factors such as weather conditions, test procedures, and specific performance requirements are critical in selecting the best option using the MCI approach, the overall findings from this study suggest that the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures containing 50% RAP were compatible with a variety of conditions and emerged as the most reliable option for use across diverse scenarios.

Several studies have applied the MCI to evaluate the circularity of recycled asphalt mixtures. Mantalovas and Di Mino29 assessed mixtures with 0%, 30%, 60%, and 90% RAP (analogous to Scenario 7 in this study), reporting that mixtures with 60% and 90% RAP exhibited superior circularity compared to lower RAP formulations. In contrast, this study demonstrates that—under a similar utility factor framework—the 50% RAP mixture achieves optimal circularity, while the 65% RAP mixture performs least favorably. This discrepancy arises from differences in rutting behavior. The current study employs a rejuvenator to mitigate stiffness in high-RAP mixtures, whereas Mantalovas and Di Mino29 analyzed unmodified mixtures, where rutting resistance improved monotonically with RAP content.

Further, da Costa et al.74 evaluated a utility factor incorporating fatigue, rutting, moisture susceptibility, tensile strength, and Cantabro abrasion for recycled asphalt mixtures incorporating cottonseed oil. Their findings revealed no direct linear relationship between RAP or cottonseed oil content and MCI, as the interaction of these parameters significantly influenced outcomes. Specifically, the 33% RAP mixture with 10% cottonseed oil yielded the highest MCI, followed by 15% RAP with 4% cottonseed oil, and 25% RAP with 6% cottonseed oil. These results align with the present study’s observation of synergistic interactions between RAP and rejuvenator content (Table 8), underscoring the need to account for combined parameter effects when interpreting MCI outcomes.

Calculation of MCIME

As previously discussed, the MCIME approach considers a combination of mechanical properties, economic factors, and environmental impacts. Given that lower cost and carbon footprint are favorable outcomes, these two parameters were included as desired properties in Eqs. (20) and (21).

In this equation, P(C), and P(E) refer to the cost and CO2 emission properties, respectively. These ratios were calculated inversely, meaning that a reduction in cost and CO2 emission indicates better performance. To identify the value of P(C), and P(E), it is necessary to calculate the cost and CO2 emission of all mixtures per ton. CO2 emissions are generated from various processes involved in the production and implementation of asphalt mixtures, including the production of aggregate, bitumen, RAP, rejuvenator, as well as the mixing operations and transportation. Table 9 provides a breakdown of the CO2 emissions associated with each of these processes, based on data from previous studies. Additionally, the costs associated with each process, extracted from previous studies and relevant data sources, are also presented in Table 9. It is mentioned that the RAP, aggregates, and bitumen are sourced from locations 35 km, 100 km, and 30 km away from the asphalt production plant, respectively.

By utilizing the CO2 emissions and cost associated with each process and material involved in asphalt mixture production, as presented in Table 9, and considering their respective quantities, the total cost and CO2 emissions for all the asphalt mixtures in this study were calculated. The resulting values are summarized in Table 10.

Using Eq. (20), the Pi values were calculated for all mixtures, and the results are presented in Table 11 for further analysis.

Considering the alternatives presented in Table 7, it is possible to incorporate the impact of cost and CO2 emissions to obtain a more comprehensive assessment of using rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures within the MCI framework, specifically the MCIME approach developed in this study. Therefore, the scenarios evaluating MCI, which include both cost and CO2 emissions, are presented in Table 12. This integrated approach allows for a more robust decision-making process when selecting suitable mixtures for different applications.

The utility factor, MCIME, and the resulting MCI values obtained from the MCIME calculations have been computed and are presented in Table 13. These values offer a comprehensive evaluation of the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures by integrating mechanical performance, cost, and environmental impact into the MCI framework, allowing for a more informed comparison of the different mixtures.

Similar to the MCI* approach, when considering all mechanical properties, as well as economic and environmental impacts, the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures containing 50% RAP emerged as the best option for use, especially when all performance factors are important. This conclusion is drawn from the MCIME results for Scenario 1.

In Scenarios 2 to 4, which represent hot climate conditions that may or may not experience intermediate and low temperatures, the cost and CO2 emissions are key criteria alongside mechanical properties. The MCIME results indicate that the best choice among the asphalt mixtures is still the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture containing 50% RAP. However, in these scenarios, the favorability of the 65% RAP mixture significantly increased compared to the MCI* evaluation, becoming the second-best option.

For Scenarios 5 and 6, which represent intermediate climates with or without low-temperature conditions, the MCIME results show no significant difference between the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures containing 50% and 65% RAP. Therefore, both mixtures are equally suitable for use in these conditions.

In the last five scenarios, which emphasize the importance of low temperatures, cost, and CO2 emissions, the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture containing 65% RAP emerged as the best option, with the 50% RAP mixture as the second-best alternative.

These findings highlight the crucial role of cost, CO2 emissions, climatic conditions, and the prioritization of specific mechanical properties in determining the MCI* and MCIME values and selecting the most appropriate asphalt mixture for each project. It is essential, however, to ensure that the minimum mechanical performance requirements are met before applying the MCI approach to identify the optimal solution.

Conclusion

In this study, the impact of various combinations of mechanical properties, cost, and CO₂ emissions on the MCI was thoroughly examined for original asphalt mixtures and three rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures containing 35%, 50%, and 65% RAP. Additionally, the effect of different testing procedures for similar mechanical properties on the MCI outcomes was investigated. Two distinct MCI calculations were performed: one incorporating mechanical, economic, and environmental factors (MCIME) and another based solely on mechanical properties (MCI*). The following key findings were derived from the study:

-

1.

The choice of testing procedure, particularly for dynamic creep tests, significantly influenced the MCI outcomes, highlighting the necessity for consistent and appropriate methodological approaches. These variations may be attributed to differences in loading frequency and magnitude, the duration of applied and rest periods, and the dimensions of the experimental samples.

-

2.

The MCI was significantly affected by the selection of different mechanical properties, regional conditions, and additional evaluative criteria. Therefore, it is crucial to first identify the most critical performance parameters and subsequently apply either the MCI* or MCIME approach to facilitate an informed selection process.

-

3.

Based on the outputs derived from various scenarios using both the MCI* and MCIME approaches, the rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixture containing 50% RAP consistently emerged as the optimal choice in most cases. Additionally, the 65% RAP mixture demonstrated superior performance in low-temperature environments. The selection of the optimal rejuvenator content was based on restoring the high PG of the blended bitumen, which comprises aged bitumen, neat bitumen, and rejuvenator. It appears that the selected rejuvenator content influences the performance of mixtures scale in different ways. Analysis of the mechanical properties indicates that the rejuvenator dosage used for the 65% RAP mixture may have exceeded the necessary level, resulting in enhanced low-temperature properties and improved performance under colder climatic conditions.

-

4.

Incorporating higher RAP content proves advantageous in reducing both the cost and environmental impact of asphalt mixtures. Consequently, selecting mixtures with elevated RAP content -provided they achieve acceptable mechanical performance in line with circular economy principles and the MCI framework- offers an effective strategy for sustainable asphalt mixture design across diverse scenarios.

This study aims to employ the MCI framework to select the most suitable asphalt mixture based on various combinations of key performance properties and to examine the influence of different testing procedures on MCI outcomes. Future research can further explore the impact of different rejuvenator types and dosages, various asphalt mixture compositions, and alternative methods for determining the optimal rejuvenator content on the MCI framework.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhong, J. et al. Quantitative evaluation of microtexture frictional properties of aggregates and reclaimed asphalt pavement. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 36 (12), 04024421 (2024).

Vidal, R., Moliner, E., Martínez, G. & Rubio, M. C. Life cycle assessment of hot mix asphalt and zeolite-based warm mix asphalt with reclaimed asphalt pavement. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 74, 101–114 (2013).

Ma, F., Sha, A., Lin, R., Huang, Y. & Wang, C. Greenhouse gas emissions from asphalt pavement construction: A case study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13 (3), 351 (2016).

Liu, S., Shukla, A. & Nandra, T. Technological, environmental and economic aspects of asphalt recycling for road construction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 75, 879–893 (2017).

Williams, B. A. Asphalt Pavement Industry Survey on Recycled Materials and Warm-Mix Asphalt Usage: 2019 (2020).

Zaumanis, M., Mallick, R. B. & Frank, R. 100% recycled hot mix asphalt: A review and analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 92, 230–245 (2014).

Rafiq, W. et al. Life cycle cost analysis comparison of hot mix asphalt and reclaimed asphalt pavement: A case study. Sustainability 13 (8), 4411 (2021).

Izaks, R., Haritonovs, V., Klasa, I. & Zaumanis, M. Hot mix asphalt with high RAP content. Procedia Eng. 114, 676–684 (2015).

Lee, J. et al. Maximising the Re-use of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement: Outcomes of Year Two: RAP Mix Design 1925294048 (2015).

T.T.S.E.U.o & Track C.C.-P.R.f.H. Roads, Asphalt Technology News, NCAT 26 (2014).

Bilema, M. et al. Mechanical performance of reclaimed asphalt pavement modified with waste frying oil and crumb rubber. Materials 14 (11), 2781 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Evaluation on the mechanical performance of recycled asphalt mixtures incorporated with high percentage of RAP and self-developed rejuvenators. Constr. Build. Mater. 269, 121337 (2021).

Moniri, A., Ziari, H., Aliha, M. & Saghafi, Y. Laboratory study of the effect of oil-based recycling agents on high RAP asphalt mixtures. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 22 (11), 1423–1434 (2019).

Moon, B., Ledtje, P. & Williams, C. Evaluating effect of rejuvenators on high RAP mixtures through laboratory performance tests and construction of field test sections. Constr. Build. Mater. 340, 127698 (2022).

Ziari, H., Ayar, P. & Amjadian, Y. Mechanical performance evaluation of crumb rubber enriched rejuvenator modified RAP mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 342, 127951 (2022).

Eltwati, A., Enıeb, M., Ahmeed, S., Al-Saffar, Z. & Mohamed, A. Effects of waste engine oil and crumb rubber rejuvenator on the performance of 100% RAP binder. J. Innov. Transp. 3 (1), 8–15 (2022).

Yin, P. & Pan, B. Effect of RAP content on fatigue performance of hot-mixed recycled asphalt mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 328, 127077 (2022).

Saltan, M. & Khaliqi, M. H. Effects of utilization of rejuvenator in asphalt mixtures containing recycled asphalt pavement at high ratios. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, e03095 (2024).

Alae, M., Zhang, Z., Xu, L., Shahsamandy, A. S. & Xiao, F. Unveiling the composite rejuvenator efficacy on performance improvement of asphalt binder including high RAP contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 446, 137989 (2024).

Arafat, S., Wasiuddin, N. M. & Mohammad, L. N. Evaluation of bio-based and petroleum-based rejuvenator based on cracking susceptibility of hot mix asphalt with high RAP content. Constr. Build. Mater. 371, 130725 (2023).

Kirchherr, J., Reike, D. & Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: an analysis of 114 definitions. Resources. Conserv. Recycl. 127, 221–232 (2017).

Fini, E. H. & Hajikarimi, P. Bio-based and Bio-inspired Pavement Construction Materials (Matthew Deans, 2024).

De Luca, A. I. et al. Life cycle tools combined with multi-criteria and participatory methods for agricultural sustainability: insights from a systematic and critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 595, 352–370 (2017).

Guinée, J. B. et al. Life Cycle Assessment: Past, Present, and Future (ACS Publications, 2011).

Fellner, J., Lederer, J., Scharff, C. & Laner, D. Present potentials and limitations of a circular economy with respect to primary raw material demand. J. Ind. Ecol. 21 (3), 494–496 (2017).

Corona, B. et al. Metrics for minimising environmental impacts while maximising circularity in biobased products: the case of lignin-based asphalt. J. Clean. Prod. 379, 134829 (2022).

Corona, B., Shen, L., Reike, D., Carreón, J. R. & Worrell, E. Towards sustainable development through the circular economy—A review and critical assessment on current circularity metrics. Resourc. Conserv. Recycl. 15, 1104498 (2019).

Mantalovas, K. & Di Mino, G. The sustainability of reclaimed asphalt as a resource for road pavement management through a circular economic model. Sustainability 11 (8), 2234 (2019).

Mantalovas, K. & Di Mino, G. Integrating circularity in the sustainability assessment of asphalt mixtures. Sustainability 12 (2), 594 (2020).

E.M. Foundation. Circularity indicators: an approach to measuring circularity. Methodology 1, 1 (2015).

EMF. Circularity indicators. An approach to measuring circularity. Methodology 1, 1–64 (2019).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Penetration of Bituminous Materials (ASTM D5, 2013).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Softening Point of Bitumen (Ring-and-Ball Apparatus) (ASTM D36, 2014).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Viscosity Determination of Asphalt at Elevated Temperatures Using a Rotational Viscometer (ASTM D4402, 2015).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Ductility of Asphalt Materials (ASTM D113, 2017).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Density of Semi-solid Asphalt Binder (Pycnometer Method) (ASTM D70, 2018).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Flash and Fire Points by Cleveland Open Cup Tester (ASTM D92, 2018).

ASTM. Standard Classification for Sizes of Aggregate for Road and Bridge Construction (ASTM D448, 2017).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Flat Particles, Elongated Particles, or Flat and Elongated Particles in Coarse Aggregate (ASTM D4791, 2019).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Determining the Percentage of Fractured Particles in Coarse Aggregate (ASTM D5821, 2013).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Fine Aggregate (ASTM C128, 2015).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Coarse Aggregate (ASTM C127, 2015).

ASTM. Standard Test Methods for Specific Gravity of Soil Solids by Water Pycnometer (ASTM D854, 2014).

Institute, A. Asphalt Mix Design Methods (MS-2, 2014).

(!!! INVALID CITATION !!! 39–48.).

Kim, Y. R. et al. Long-Term Aging Asphalt Mixtures Perform. Test. Prediction: Phase III Results 0309460018 (2021).

Gholami, M., Khodaii, A. & Hajikarimi, P. Long-term aging simulation of asphalt mixture: A comparative experimental study. Constr. Build. Mater. 435, 136856 (2024).

ASTM. Standard Test Methods for Quantitative Extraction of Bitumen from Bituminous Paving Mixtures (ASTM D2172, 2011).

ASTM. Standard Practice for Recovery of Asphalt from Solution Using the Rotary Evaporator (ASTM D5404, 2012).

Association, E. A. P. Recommendations for the Use of Rejuvenators in Hot and Warm Asphalt Production (European Asphalt Pavement Association, 2018).

Arámbula-Mercado, E., Kaseer, F., Martin, A. E., Yin, F. & Cucalon, L. G. Evaluation of recycling agent dosage selection and incorporation methods for asphalt mixtures with high RAP and RAS contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 158, 432–442 (2018).

Daryaee, D., Ameri, M. & Mansourkhaki, A. Utilizing of waste polymer modified bitumen in combination with rejuvenator in high reclaimed asphalt pavement mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 235, 117516 (2020).

Zaumanis, M., Mallick, R. B. & Frank, R. Determining optimum rejuvenator dose for asphalt recycling based on superpave performance grade specifications. Constr. Build. Mater. 69, 159–166 (2014).

Tran, N. H. Effect of Rejuvenator on Performance Properties of HMA Mixtures with High RAP and RAS Contents. NCAT Report, vol. 1 (2012).

Nsengiyumva, G., Haghshenas, H. F., Kim, Y. R. & Kommidi, S. R. Mechanical-chemical characterization of the effects of type, dosage, and treatment methods of rejuvenators in aged bituminous materials. Transp. Res. Rec. 2674 (3), 126–138 (2020).

Ma, Y. et al. Rheological and aging characteristics of the recycled asphalt binders with different rejuvenator incorporation methods. J. Clean. Prod. 262, 121249 (2020).

Administration, F. H. User Guidelines for Waste and Byproduct Materials in Pavement Construction (FHWA-RD-97-148, 2011).

AASHTO. Standard Method of Test for Determining the Dynamic Modulus and Flow Number for Asphalt Mixtures Using the Asphalt Mixture Performance Tester (AMPT) (AASHTO T378, 2017).

B. EN. Bituminous Mixtures-Test Methods. Part25: Cyclic Compression Test (BS-EN 12697-25, 2016).

AASHTO. Standard Method of Test for Resistance of Compacted Asphalt Mixtures To Moisture-Induced Damage (AASHTO T283, 2022).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Determining the Resilient Modulus of Bituminous Mixtures by Indirect Tension Test (ASTM D7369, 2011).

B. EN. Bituminous Mixtures—Test Methods for Hot Mix Asphalt Part 24: Resistance to Fatigue (BS EN 12697–12624, 2012).

Cheng, H., Sun, L., Wang, Y., Liu, L. & Chen, X. Fatigue test setups and analysis methods for asphalt mixture: A state-of-the-art review. J. Road. Eng. 2 (4), 279–308 (2022).

Cheng, H., Liu, J., Sun, L., Liu, L. & Zhang, Y. Fatigue behaviours of asphalt mixture at different temperatures in four-point bending and indirect tensile fatigue tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 273, 121675 (2021).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Determining Fatigue Failure of Compacted Asphalt Concrete Subjected to Repeated Flexural Bending (ASTM 7460, 2019).

AASHTO. Standard Method of Test for Determining the Fracture Energy of Asphalt Mixture Using the Semicircular Bend Geometry (SCB) (AASHTO TP105, 2020).

Zaumanis, M. & Mallick, R. B. Review of very high-content reclaimed asphalt use in plant-produced pavements: state of the Art. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 16 (1), 39–55 (2015).

West, R. C. et al. Improved Mix Design, Evaluation, and Materials Management Practices for Hot Mix Asphalt with High Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement Content (Transportation Research Board, 2013).

Zhou, Z., Gu, X., Li, Q., Ni, F. & Yuan, R. Use of rejuvenator, styrene-butadiene rubber latex, and warm-mix asphalt technology to achieve conventional mixture performance with 50% reclaimed asphalt pavement. Transp. Res. Rec. 2575 (1), 160–167 (2016).

Jahanbakhsh, H., Karimi, M. M., Naseri, H. & Nejad, F. M. Sustainable asphalt concrete containing high reclaimed asphalt pavements and recycling agents: performance assessment, cost analysis, and environmental impact. J. Clean. Prod. 244, 118837 (2020).

AASHTO. AASHTO Guide for Design of Pavement Structures (1993).

Abbas Mukhtar, J. W. & Adnan Evaluation of the mechanical performance of asphalt mixtures containing waste tire rubber and graphene. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 36, 12 (2024).

Li, X. & Marasteanu, M. Evaluation of the low temperature fracture resistance of asphalt mixtures using the semi circular bend test. In Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists-Proceedings of the Technology Sessions, AAPT 2004 401–426 (2004).

da Costa, L. F. et al. Optimizing recycled asphalt mixtures with zeolite, cottonseed oil, and varied RAP content for enhanced performance and circular economy impact. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, e02707 (2024).

Xiao, F., Su, N., Yao, S., Amirkhanian, S. & Wang, J. Performance grades, environmental and economic investigations of reclaimed asphalt pavement materials. J. Clean. Prod. 211, 1299–1312 (2019).

Van Fan, Y., Perry, S., Klemeš, J. J. & Lee, C. T. A review on air emissions assessment: transportation. J. Clean. Prod. 194, 673–684 (2018).

Kaliampakos, D. & Benardos, A. Quarrying and sustainable development in large urban centres: A contradiction in terms? CIM Bull. 93, 86–89 (2000).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Tabriz for financially supporting this study within the scope of the Cooperation Agreement between the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK) and the Iranian Ministry of Science, Research and Technology (MSRT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Gh: Performing Experiments, Writing, Reviewing and Editing, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Visualization; A.Kh: Reviewing and Editing, Conceptualization, Supervision; P.H.: Reviewing and Editing, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Visualization, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gholami, M., Khodaii, A. & Hajikarimi, P. A multifaceted purpose-oriented approach to evaluate material circularity index for rejuvenated recycled asphalt mixtures. Sci Rep 15, 12213 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96749-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96749-2