Abstract

Orthopoxvirus (OPXV) genus includes emerging and re-emerging zoonotic viruses that pose threats to global health. Smallpox caused pandemics in the 20th century. Borealpox was responsible for a death in Alaska in 2024. Mpox, declared a Public Health Emergency by the WHO in 2022, with an alert reclassification in 2024. The lack of effective therapies and the limitations of attenuated virus vaccines, especially for immunocompromised individuals, reinforce the urgent need for new strategies to prevent diseases caused by pathogens of the OPXV genus. This study aimed to identify conserved epitopes in proteins essential for the entry and exit of these viruses and, based on this identification, develop a promising multivalent vaccine candidate. Viral protein sequences were extracted from the NCBI Virus database, and 160 sequences were analyzed to identify conserved epitopes using the Immune Epitope Database. After filtering the data, epitopes were concatenated to create a chimeric multi-epitope protein combined with β-defensin and PADRE adjuvants. The resulting protein, with eight conserved epitopes covering all OPXV viruses (including Mpox Clade Ib), was evaluated for antigenicity, allergenicity, and structural stability. It showed strong interaction with the TLR2 receptor, along with good predictions for immune responses after three doses. This proposed multivalent vaccine represents a potential approach against these zoonotic viruses, with promising results for in vitro and in vivo studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emerging viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2 and re-emerging ones, such as Monkeypox (Mpox), pose constant challenges to global health1. While the former emerges unexpectedly and can cause sudden and devastating epidemics, the latter, although previously documented, resurface significantly, requiring continuous surveillance2. Recently, the Mpox virus, belonging to the genus Orthopoxvirus (OPXV), has once again become an international concern3.

OPXV, part of the Poxviridae family, is one of the most significant viral genera for human health4. These viruses, characterized by their double-stranded DNA and complex structure, have a broad host spectrum, including various animal species, classifying them as zoonotic2,4. Although many are named after the animals with which they are associated, it is believed that these animals primarily act as vectors rather than the original sources of the viruses4.

Currently, 16 species are recognized under the OPXV genus, including Abatino, Akhmeta, Borealpox, Buffalopox, Camelpox, Cowpox, Ectromelia, Horsepox, Monkeypox, Rabbitpox, Raccoonpox, Skunkpox, Taterapox, Vaccinia, Variola, and Volepox2,5. In particular, the Variola virus (VARV), the causative agent of smallpox, was responsible for one of the most devastating pandemics of the 20th century, resulting in approximately 300 to 500 million deaths4,6. Smallpox was officially eradicated in 1980, due to a global vaccination program2,7. However, with the decline in immunization, the risk of OPXV transmission has grown, raising concerns about the morbidity of these zoonotic infections8.

In recent years, outbreaks of OPXV infections have been recorded in various animals around the world. Cases of Cowpox, Camelpox, Buffalopox, and Mpox have been reported in Europe, the Middle East, India, South America, Africa, and the United States8. Moreover, new emerging viruses from this genus continue to be identified globally, such as the Alaskapox virus (recently renamed Borealpox), which caused the first death of an immunocompromised patient earlier this year9.

Among the viruses of the OPXV genus, Mpox has stood out due to its recent global impact3. Although it shares symptoms similar to smallpox, Mpox is distinguished by characteristic skin lesions10. Initially restricted to the African continent, Mpox was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2022, following a significant increase in cases, including around 100,000 reported infections worldwide11. In 2024, the WHO reaffirmed this global emergency due to the evolution of Clade Ib, which demonstrated higher transmissibility and the ability to spread to other continents3.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), two vaccines are available for the prevention of infections caused by OPXV: ACAM2000 and JYNNEOS2. Both are licensed for use in at-risk individuals who have had contact with Mpox-infected persons and are being administered to contain current outbreaks2. However, as they use attenuated viruses, these vaccines are contraindicated for immunocompromised individuals and other at-risk groups2.

In this context, our research group previously developed an in silico multi-epitope vaccine candidate for Mpox, focusing on the viral entry and exit proteins in the host cell12. Additionally, we identified three Mpox epitopes that are fully conserved in proteins similar to those of the Borealpox virus13. These findings led us to suggest that conserved epitopes might be present across the entire OPXV genus13.

Based on this hypothesis, the presence of conserved epitopes in the ten key proteins involved in OPXV entry and exit would enable the development of a next-generation vaccine candidate capable of targeting different regions of the viruses. This would potentially trigger a broad and specific immune response against viruses of the OPXV genus, even simultaneously. This approach represents a novelty that has not yet been reported in the literature for this genus.

The aim of this study is to identify conserved epitopes in ten key proteins involved in the viral entry and exit process across all 16 viruses belonging to the OPXV genus, with particular attention to the emerging Mpox Clade Ib sub-lineage. If these epitopes are identified, we intend to construct, develop, and validate an immunogenic multi-epitope chimeric vaccine for the OPXV genus, providing a broader and more effective approach to combating these viruses.

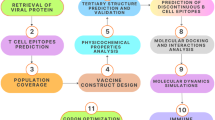

Materials and methods

Obtaining protein sequences from viruses of the OPXV genus

The proteins involved in the viral entry mechanisms into the host cell (A17L, A28L, A33R, H2R, L1R), exit (A27L, A35R, A36R, C19L), and in both processes (B5R) of all viruses of the OPXV genus were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Virus (NCBI Virus) database using the identifier “taxid:10242”12,14. The Mpox virus Clade Ib sub-lineage sequences were obtained from the PQ220056.1 sequence, deposited in the NCBI. To ensure the acquisition of proteins for all organisms, the selection followed this order: I—Selection of reference proteins (RefSeq); II—Selection of other proteins and generation of a consensus sequence when RefSeq were not found; III—BLAST for sequence similarity; IV—Proteins from the PQ220056.1 sequence. If the protein was not found by these methods, it was determined to be absent.

Determination of consensus sequences and identification of epitopes for BCR, MHC-I, and MHC-II receptors

Consensus sequences for each protein, when necessary, were obtained using the Jalview software15. The RefSeq and consensus sequences were submitted to the Immune Epitope Database and Analysis Resource (IEDB) server for epitope identification16. For BCR epitopes, the BepiPred Linear Epitope Prediction 2.0 tool was used with a cutoff of 0.5. For MHC-I epitopes, the NetMHCpan EL 4.1 tool was used, selecting peptide options with sizes ranging from 8 to 14 amino acids and a reference set of 27 alleles, representing 97–99% of the global population. For MHC-II epitopes, the same tool was used, with peptides of 15 amino acids and a reference set of 7 HLA alleles. After obtaining the epitopes, the following exclusion criteria were applied: for MHC-I, a cutoff limit of 1% of epitopes interacting with each allele was established, ensuring an equal number of epitopes for each allele. For MHC-II, a consensus percentile cutoff of < = 10.0 was defined. For BCR, all found epitopes were selected. All cutoff thresholds followed the recommendations of the platform16.

Analysis of antigenic, allergenic, and physicochemical properties

For the antigenicity analysis, the VaxiJen 2.0 server was used, configured to recognize the target organism as a virus with a cutoff threshold of 0.517. For allergenicity assessment, the AllerCatPro 2.0 server was used, following the default settings18. For the analysis of physicochemical properties, the ProtParam tool from the Biopython library was used, with a structural stability parameter set to < 40.

Alignment, consensus epitope determination, and validation of epitope regions

The epitopes approved in all previous stages were aligned with the sequences of all viruses for each specific protein using the Jalview software, through the ClustalW plugin. Conserved regions for each protein were identified, defined as those with at least eight conserved amino acids in all sequences and containing at least one epitope aligned with the region. Conserved regions located in transmembrane areas and containing N-glycosylation sites were identified using the SOSUI19 server and NetNGlyc 1.0 server20, respectively, and they were removed from the analysis.

Construction of a multi-epitope chimeric protein with conserved epitopes

Four multi-epitope chimeric proteins were created: I - containing the epitopes with the highest antigenicity value from each protein; II - with all conserved epitopes from the A17L protein; III - with all conserved epitopes from the H2R protein; and IV - with all conserved epitopes from the C19L protein. In the construction of chimeric protein I, the epitopes were arranged in sequence (entry, both, and exit). The other chimeric proteins were designed based on the increasing antigenicity value of the epitopes. To link the epitopes, the AAY linker was used to provide flexibility to the proteins12,13. At the beginning of the proteins, two adjuvants, PADRE and beta-defensin, were added using the EAAAK linker to provide a more rigid characteristic to these adjuvants12,13. At the end of the protein, a HIS-tag (HIS, 6x) was added.

Evaluation of the multi-epitope chimeric protein properties

Allergenicity, toxicity, and physicochemical properties were evaluated using the servers Vaxijen, AllerCatPro 2.0, and ProParam, respectively. The search for potential autoimmune responses was conducted by aligning the sequence of the multi-epitope chimeric protein with human and murine genomes using the BLASTp tool. The solubility analysis of the proteins was performed on the SoluProt 1.0 server, where proteins with values > 0.5 are considered soluble21. The chimeric protein was submitted to the C-ImmSim server for immune response profile prediction using the following parameters: single injection, random seed = 12,345, injection without LPS, simulation volume of 10, and 300 simulation steps, with doses set at 1, 100, and 200 steps, representing days 0, 30, and 60 respectively, where both humoral and cellular responses were analyzed22.

Modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics

For molecular modeling by homology and molecular docking, the AlphaFold Server was used, powered by the new AlphaFold3 and AlphaFold2 prediction model23. The amino acid sequences of the multi-epitope chimeric proteins and the TLR2 receptor, available in the PDB under code 2Z7X, were provided to the tool. Additionally, ClusPro 2.0 was used to perform molecular docking between the multi-epitope protein and TLR2 receptor for comparative analysis. Molecular dynamics simulation was performed using GROMACS 2019.3 software with the OPLS-AA/L force field24. The water equilibrium under NVT (Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature constant) and NPT (Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature constant) conditions was maintained for 100 ps, at a temperature of 300 K and pressure of 1 bar. Subsequently, a 100 ns simulation was conducted, and RMSD values were generated by GROMACS24.

Results

Protein profile of selected OPXV genus viruses

The proteins responsible for entry (A17L, A28L, A33R, H2R, L1R), exit (A27L, A35R, A36R, C19L), and both (B5R) of viruses from the OPXV genus were obtained in FASTA format from the NCBI Virus database. The “taxid:10242”, which covers all organisms of this genus, was selected. A total of 16 virus species were identified, including Orthopoxvirus Abatino, Akhmeta virus, Borealpox virus, Buffalopox virus, Camelpox virus, Cowpox virus, Ectromelia virus, Horsepox virus, Monkeypox virus, Rabbitpox virus, Racoonpox virus, Skunkpox virus, Taterapox virus, Vaccinia virus, Variola virus, and Volepox virus.

Among these, nine have RefSeq for all studied proteins, four have RefSeq for nine of the ten proteins, necessitating the generation of a consensus for one protein. Three viruses do not have reference sequences; thus, the available proteins were collected, and a consensus was generated. It is important to note that Rabbitpox virus was the only one with a protein (A27L) found by BLAST, and Mpox virus had two RefSeqs for each protein, corresponding to clades I and II, except for A27L, for which a consensus sequence was generated.

For sequencing of the Mpox clade Ib virus, the PQ220056.1 sequencing was used, with the respective proteins aligned and identified. The A27L protein was not found and thus was marked as absent. All data are detailed in Table 1.

Antigenic, non-allergenic, and stable epitopes identified in conserved regions of eight proteins

The IEDB server was used to find epitopes that can bind to MHC-I, MHC-II, and BCR, with all parameters set by the server. A global consensus sequence was generated for each of the ten proteins from each virus. The epitopes were identified, collected, and subjected to antigenicity analysis on the VaxiJen server, and their stability was assessed using the ProtParam tool from the Biopython library. It was noted that there were more epitopes for MHC-I and MHC-II receptors compared to BCR (Table 2).

The obtained epitopes were aligned using Jalview software and the ClustalW tool with the proteins from the sixteen viruses to identify conserved epitopes across all proteins, i.e., conservation regions that had at least one epitope were selected (Table 2).

Proteins A28L and B5R, although having conserved regions, did not show the presence of epitopes in these regions or, when present, the epitopes did not fully occupy these regions, failing to meet the minimum length of 8 amino acids. A total of 26 epitopes were identified and none of them presented evidence of allergenicity using the AllerCatPro 2.0. The amino acid sequences of each conserved epitope along with their respective antigenicity values are presented in Table 3. It is worth noting that the identified conserved epitopes are also present in the new Mpox variant, clade Ib. Although proteins A17L, A36R, C19L, and L1R have mutations in their protein composition, the identified epitopes remain conserved in this new variant (Fig. 1).

Analysis of the A17L, A36R, C19L, and L1R proteins from the new Mpox virus lineage (Clade Ib), sequenced in 2024. The conservation percentages of these proteins compared to Clade I are indicated to the right of each protein. Conserved epitopes are highlighted in blue, mutations in red, transmembrane regions in yellow, and N-glycosylation sites in green. (A) Protein A17L with 99.20% conservation, displaying multiple conserved epitopes but with mutations outside these regions. (B) Protein A36R with 99.40% conservation, showing one mutation and one conserved epitope. (C) Protein C19L with 99.46% conservation, revealing several mutations and conserved epitopes. (D) Protein L1R with 99.34% conservation, having two conserved epitopes and one mutation outside these regions. The identified mutations do not affect the conserved epitopes, suggesting that they remain preserved in this new virus lineage.

The new Mpox sublineage, declared a global emergency by the WHO due to the evolution of Clade Ib, has demonstrated increased transmissibility and the ability to spread to other continents3. Therefore, it is crucial to verify if conserved epitopes remain preserved in this new variant. Sequencing conducted in 2024 on patients from the Democratic Republic of Congo regarding the new Clade Ib lineage is available on NCBI under code PQ220056.125, and it was used for analysis. The A27L protein was not found, which is consistent with the results in Table 1, where A27L is the only analyzed Mpox protein without a RefSeq. Additionally, among the eight proteins with conserved epitopes, A33R, A35R, and H2R are 100% conserved, ensuring epitope conservation (Fig. 1A). The A17L, A36R, C19L, and L1R proteins show 99.20%, 99.40%, 99.46%, and 99.34% conservation, respectively, compared to Mpox Clade I proteins; however, mutations do not occur in the identified epitopes (Fig. 1B–D).

Characterization and evaluation of the constructed multi-epitope chimeric proteins indicate adequate physicochemical properties, absence of allergenicity, good antigenicity, and positive humoral and cellular immune responses

After identifying the epitopes for each protein, four multi-epitope chimeric proteins were constructed. Two adjuvants were selected and added to the beginning of the chimeric protein: PADRE, a synthetic epitope capable of binding to MHC-II, which enhances the immune response by increasing the activation and proliferation of helper T cells, and β-defensin, which stimulates both the innate and adaptive immune responses12. It is worth noting that the chimeric proteins related to A17L, C19L, and H2R were created individually as they were the only ones presenting more than one conserved epitope.

The chimeric protein constructs range from 146 to 173 amino acids, molecular weights varying from 16 to 19 kDa, and isoelectric points of approximately 9, indicating a basic nature for all proteins. Furthermore, all proteins meet the cut-off thresholds for stability, antigenicity, allergenicity, solubility, and autoimmunity, indicating that they are suitable for vaccination (Table 4).

Subsequently, the simulation of the possible immune response to the four vaccine candidates was conducted on the C-ImmSim server. The multi-epitope protein containing epitopes from different proteins exhibited lower IgM + IgG titers compared to the vaccine candidates based on individual proteins (Fig. 2A). Additionally, the population of memory B cells was lower in the vaccine candidate containing epitopes from different proteins during the first 30 days, with an increase observed after the second dose administration. Comparing the cellular response, IFN-γ cytokine production was similar among the four vaccine candidates, while variations were observed in the levels of IL-2, TGF-β, IL-10, and IL-12 (Fig. 2A–D). All four vaccine candidates showed nearly null values for the “Danger” variable (Fig. 2A–D).

The constructed multiepitope chimeric proteins show satisfactory predictions for cellular and humoral responses after three doses. Cytokine and interleukin levels after 3 doses are displayed, with “D” in the graph indicating a potential danger signal. (A) Results for the chimeric protein containing epitopes from different proteins. (B) Protein with epitopes from A17L. (C) Protein with epitopes from C19L. (D) Protein with epitopes from H2R.

Structural stability and interaction with the TLR-2 receptor of the multivalent chimeric protein: modeling and molecular dynamics reveal good stability and fluctuation patterns

To determine the three-dimensional structure of the vaccine candidates and assess their interaction capability with the TLR-2 receptor, the AlphaFold 3 server was used. The predicted template modeling (pTM) score, interface predicted template modeling (ipTM) score, and per-residue measure of local confidence (pLDDT) were evaluated for each vaccine candidate. The modeling showed similarities, with TLR-2 exhibiting high pLDDT values, while the vaccine candidates showing low values. It was observed that the adjuvant region is responsible for anchoring to TLR-2 (Fig. 3A–D). Additionally, the pTM values ranged between 0.70 and 0.73, suggesting that the overall folds are close to the true structure, as values above 0.5 indicate good correspondence. However, ipTM values ranged from 0.20 to 0.22, indicating a potential failure in predicting the interaction. Therefore, validation of the structures through molecular dynamics was necessary.

The constructed chimeric proteins interact with the Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2), with modeling indicating good results for the receptor. However, the multiepitope proteins show low reliability. The multiepitope chimeric protein from different proteins demonstrates stability after 20 nanoseconds, maintaining a good interaction with TLR-2. (A) Modeling and binding of the multiepitope protein with TLR-2. (B) Binding of the A17L epitope protein with TLR-2. (C) Multiepitope from C19L and TLR-2. (D) Multiepitope from H2R and TLR-2. (E) RMSD obtained after 100 ns of molecular dynamics of the TLR-2 complex with the multiepitope protein. (F) RMSF of the multiepitope protein. (G) RMSF of TLR-2.

Molecular dynamics was performed exclusively with the chimeric protein containing epitopes from different proteins due to its potential representativeness and comprehensiveness for immunization against the OPXV genus. Structural stability over time was assessed using the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) graph, and the protein’s residual fluctuation was analyzed with the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) graph. The RMSD graph showed that the protein reached stability after 20 ns and remained stable until the end of the simulation (100 ns), with a structural variation from 0.4 nm to 0.5 nm (Fig. 3E). The RMSF graph indicated low variation in the initial part of the chimeric protein, with an increase in fluctuation occurring in the last amino acids of the protein (Fig. 3F). In contrast, the TLR-2 receptor exhibited a characteristic fluctuation pattern, with two fluctuation peaks occurring between amino acids 200 and 300 (Fig. 3G).

Additionally, analyses of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) and the radius of gyration (Rg) were conducted, as presented in Supplementary Fig. S1. The data show that the interaction complex between the TLR-2 receptor and the multi-epitope protein, composed of epitopes from different proteins, maintained between 450 and 550 hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation (Supplementary Fig. S1A). The radius of gyration ranged from 3.00 to 3.14 nm (Supplementary Fig. S1B), corroborating the RMSD values presented in Fig. 3E. These results indicate the preservation of structural integrity and stability of amino acid interactions during the 100 ns simulation, demonstrating the structural viability of the complex.

Discussion

The OPXV genus, with its 16 documented species and new emerging threats, continues to pose an increasing concern for global health2,3,5. Vaccination is a crucial strategy to prevent these potentially fatal diseases, but current vaccines like ACAM2000 and JYNNEOS, which use attenuated viruses, are unsuitable for immunocompromised patients, as reported by the CDC2. Therefore, subunit vaccines, designed with computational techniques, offer a promising alternative to overcome these limitations and address genetic and antigenic variations12.

In 2024, our research group reported the presence of immunogenic epitopes in the Mpox virus, developing an in silico multiepitope vaccine candidate targeting viral entry and exit processes proteins12. We also observed the conservation of these epitopes in Borealpox virus proteins, suggesting that conserved epitopes may exist throughout the OPXV genus13. In this study, we identified 26 conserved epitopes in eight proteins related to viral entry and release processes across the 16 OPXV species. These conserved epitopes can act as targets for neutralizing antibodies or induce a T-cell mediated cellular response12,13.

OPXV viruses share similarities in viral entry and exit processes, making their proteins ideal targets for vaccine development26. The A17L, a myristoylated protein, and A27L, an inclusion body type A protein, facilitate viral entry, while A28L, the membrane protein L1R, and the fusion complex H2R are essential for virus penetration into the cytoplasm27. Being exposed during viral entry, these proteins are more susceptible to immune system recognition26. Similarly, A33R, A35R, A36R, B5R, and C19L proteins, involved in the formation and maturation of extracellular viral particles (EEV), play a crucial role in virus dissemination27 (Fig. 4).

Entry and exit proteins of Orthopoxvirus in the host cell. In the upper part of the figure, the A17L protein is involved in the virus’s entry into the host cell; subsequently, the viral membrane proteins A28L, H2R, and L1R facilitate the fusion of the virus with the host cell, with A28L also enabling the formation of viral inclusions, assisting in the virus entry. In the lower part of the figure, the A33R and C19L proteins contribute to the formation of extracellular viral particles. The A35R protein is involved in the formation and maturation of extracellular enveloped virions (EEV); the B5R protein is essential for the formation of EEV and for the release of the virus; and finally, the A36R protein facilitates the virus’s exit and the infection of neighboring cells. A17L Myristylate protein for entry, A27L A-type inclusion protein, A28L Truncated P4c or P4c/ATI inclusion factor, A33R CPXV166 protein, A35R EEV membrane phosphoglycoprotein, A36R IEV and EEV membrane glycoprotein, B5R Ankyrin-containing protein, C19L Palmytilated EEV membrane protein, H2R Entry-fusion complex essential component, L1R IMV membrane protein J1.

The use of conserved epitopes, as well as their validation in in vitro and in vivo tests for other viruses like SARS-CoV-2 and hepatitis C, has been reported in the literature28,29,30.

The OPXV conserved epitopes were combined with β-defensins and PADRE adjuvants into four vaccine candidates: one containing epitopes from multiple proteins, and others specific to A17L, C19L, and H2R. The use of the pipeline presented in this study reinforces the accuracy and reliability of the proposed approach, as it was also compared with a traditional workflow involving molecular modeling, molecular dynamics simulation, and molecular docking using previous-generation tools, such as AlphaFold2 and ClusPro 2.012. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, the AlphaFold3-based strategy not only reduces the number of steps required for multi-epitope vaccine development but also provides superior structural modeling quality when compared to AlphaFold2. Furthermore, AlphaFold3 accurately predicted the interaction between the vaccine construct and the TLR2 receptor, clearly illustrating the interaction of adjuvants with the receptor.

These chimeric proteins aim to induce local immune responses, including the production of inflammatory cytokines by macrophages12,13. Captured by dendritic cells or macrophages, these antigens are presented on the surface by MHC molecules, allowing recognition by T-cell receptors and resulting in the generation of memory T-cells and the development of adaptive immunity7,8. Additionally, the presence of B-cell specific epitopes is essential for antibody production, and a multiepitope vaccine that interacts with both T-cell and B-cell receptors can effectively stimulate both humoral and cellular responses7,8,11.

Immunological simulation revealed a decrease in IgM + IgG titration for the candidate with multiple protein epitopes compared to the multiepitope protein developed for Mpox and individual protein candidates12. This variation in humoral response may be attributed to differences in protein immunogenicity, as the focus of this study is on conserved epitopes rather than the most immunogenic of a protein. However, the cellular immune response, mediated by cytokines such as IFN-γ, TGF-β, IL-2, IL-10, and IL-12, remained similar, indicating a consistent Th1 and regulatory profile. Furthermore, the robust cellular response suggests that both vaccines are effective in activating T-cells.

The results, introduce a new approach to vaccine development against OPXV genus viruses. The identification of conserved epitopes across different viruses demonstrates potential to induce robust humoral and cellular immune responses, even against the genetic diversity of these pathogens. We report the presence of conserved epitopes in eight OPXV genus proteins related to viral entry and exit processes in host cell.

As this study is based exclusively on in silico analyses, additional in vitro and in vivo studies are required to confirm the structural stability, immunogenic potential, and safety of the proposed multi-epitope vaccine candidate. Nevertheless, the structural, dynamic, and immunological data obtained strongly support the biological plausibility of the construct and provide a solid foundation for its future application not only as a prophylactic vaccine but also as a potential immunodiagnostic tool for all 16 Orthopoxvirus species.

Conclusion

It is evident that emerging and re-emerging viruses of the OPXV genus pose a persistent concern. Currently, vaccination is the most effective method against infections caused by this viral genus. In this study, we reported 26 conserved epitopes in key proteins and developed, as well as validated in silico, four multiepitope vaccine candidates. Analyses of antigenicity, allergenicity, structural stability, prediction of humoral and cellular immune responses, as well as the three-dimensional evaluation of interaction with the innate immune receptor TLR-2, indicated that the vaccine candidate with conserved epitopes from eight different proteins showed promising results.

This approach, combined with in vitro and in vivo testing, will be crucial for validating and refining the proposed vaccine candidates, strengthening the development of effective vaccines against the OPXV genus.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the NCBI database under Taxid 10242 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/virus/vssi/#/virus?SeqType_s=Nucleotide&VirusLineage_ss=Orthopoxvirus,%20taxid:10242) and in the PDB database under the code 2Z7X (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/2Z7X). Additionally, the following protein sequences were utilized in this study: Mpox virus Clade Ib sub-lineage: PQ220056.1.Protein A17L: YP_010085594.1, QED21147.1, NP_570524.1, NP_619932.1, NP_671638.1, YP_010509346.1, YP_010377125.1, NP_536554.1, YP_010085803.1, AAS49838.1, YP_009143444.1, YP_009282829.1, YP_717445.1, YP_233018.1, NP_042164.1, YP_009281883.1.Protein A27L: YP_010085604.1, QED21098.1, NP_570534.1, NP_619942.1, NP_671647.1, YP_010085812.1, YP_009282838.1, YP_717456.1, YP_233030.1, NP_042176.1, YP_009281892.1.Protein A28L: YP_010085605.1, QED21129.1, NP_570535.1, AUO16291.1, YP_010509355.1, YP_010377134.1, NP_536565.1, YP_010085813.1, AAS49847.1, YP_009143454.1, YP_009282839.1, YP_717457.1, YP_233031.1, YP_009281893.1.Protein A33R: YP_010085610.1, QED21259.1, NP_570540.1, NP_619950.1, NP_671652.1, YP_010509361.1, YP_010377140.1, NP_536570.1, YP_010085820.1, AAS49852.1, YP_009143460.1, YP_009282845.1, YP_717462.1, YP_233036.1, NP_042182.1, YP_009281899.1.Protein A35R: YP_010085610.1, QED21259.1, NP_570540.1, NP_619950.1, NP_671652.1, YP_010509361.1, YP_010377140.1, NP_536570.1, YP_010085820.1, AAS49852.1, YP_009143460.1, YP_009282845.1, YP_717462.1, YP_233036.1, NP_042182.1, YP_009281899.1.Protein A36R: YP_010085613.1, QED21233.1, AVO21161.1, NP_570543.1, NP_619953.1, NP_671655.1, YP_010509364.1, YP_010377143.1, NP_536573.1, YP_010085823.1, AAS49855.1, YP_009143463.1, YP_009282848.1, YP_717465.1, YP_233039.1, NP_042185.1, YP_009281902.1.Protein B5R: YP_010085641.1, QED21126.1, NP_570570.1, NP_619979.1, NP_671673.1, YP_010509386.1, YP_010377161.1, NP_536593.1, YP_010085850.1, AAS49879.1, YP_009143489.1, YP_009282875.1, YP_717494.1, YP_233068.1, NP_042218.1, YP_009281929.1.Protein C19L: YP_010085505.1, QED21148.1, NP_570438.1, NP_619848.1, NP_671554.1, YP_010509261.1, YP_010377040.1, NP_536472.1, YP_010085720.1, AAS49754.1, YP_009143359.1, YP_009282743.1, YP_717360.1, YP_232934.1, NP_042081.1, YP_009281797.1.Protein H2R: YP_010085556.1, QED21222.1, AVO21113.1, NP_570488.1, NP_619896.1, NP_671602.1, YP_010509310.1, YP_010377089.1, NP_536519.1, YP_010085768.1, AAS49802.1, YP_009143408.1, YP_009282793.1, YP_717409.1, YP_232982.1, NP_042129.1, YP_009281847.1.Protein L1R: YP_010085549.1, QED21242.1, NP_570481.1, NP_619889.1, NP_671595.1, YP_010509303.1, YP_010377082.1, NP_536512.1, YP_010085761.1, AAS49795.1, YP_009143401.1, YP_009282786.1, YP_717403.1, YP_232975.1, NP_042122.1, YP_009281840.1.

References

Choi, Y. K. Emerging and re-emerging fatal viral diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 53 (5), 711–712 (2021).

Mpox Vaccination from CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/interim-considerations/overview.html (Accessed 25 August 2024).

Adepoju, P. Mpox declared a public health emergency. Lancet 404 (10454), e1–e2 (2024).

Babkin, I. V., Babkina, I. N. & Tikunova, N. V. An update of orthopoxvirus molecular evolution. Viruses 14 (2), 388 (2022).

Molteni, C. et al. Evolution of the orthopoxvirus core genome. Virus Res. 323, 198975 (2023).

Mühlemann, B. et al. Diverse variola virus (smallpox) strains were widespread in Northern Europe in the Viking age. Science 369 (6502), eaaw8977 (2020).

Shchelkunova, G. A. & Shchelkunov, S. N. Smallpox, Monkeypox and other human orthopoxvirus infections. Viruses 15 (1), 103 (2022).

Diaz, J. H. The disease ecology, epidemiology, clinical manifestations, management, prevention, and control of increasing human infections with animal orthopoxviruses. Wilderness Environ. Med. 32 (4), 528–536 (2021).

Devi, S. First fatality from Alaskapox virus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24 (5), e282 (2024).

Walter, K. & Malani, P. N. What is Monkeypox? JAMA 328 (2), 222 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Three neutralizing mAbs induced by MPXV A29L protein recognizing different epitopes act synergistically against orthopoxvirus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 12 (2), 2223669 (2023).

De Araújo, L. P. et al. Immunoinformatic approach for rational identification of Immunogenic peptides against host entry and/or exit Monkeypox proteins and potential multi-epitope vaccine construction. J. Infect. Dis. 229 (Supplement_2), S285–S292 (2024).

De Araújo, L. P. et al. Shared Immunogenic epitopes between host entry and exit proteins from Monkeypox and Alaskapox viruses. Lancet Microbe. 5 (7), 624–625 (2024).

Hatcher, E. L. et al. Virus variation resource–improved response to emergent viral outbreaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (D1), D482–D490 (2017).

Waterhouse, A. M. et al. Jalview version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25 (9), 1189–1191 (2009).

Vita, R. et al. The immune epitope database (IEDB): 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 (D1), 339–343 (2019).

Doytchinova, I. A. & Flower, D. R. VaxiJen: a server for prediction of protective antigens, tumour antigens and subunit vaccines. BMC Bioinf. 8, 1–7 (2007).

Nguyen, M. N. et al. AllerCatPro 2.0: a web server for predicting protein allergenicity potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 50 (W1), W36–W43 .

Hirokawa, T., Boon-Chieng, S. & Mitaku, S. SOSUI: classification and secondary structure prediction system for membrane proteins. Bioinformatics 14 (4), 378–379 (1998).

Gupta, R. & Brunak, S. Prediction of glycosylation across the human proteome and the correlation to protein function. In Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 310–322. (2002).

Hon, J. et al. SoluProt: prediction of soluble protein expression in Escherichia coli. Bioinformatics 37 (1), 23–28 (2021).

Rapin, N. et al. Computational immunology Meets bioinformatics: the use of prediction tools for molecular binding in the simulation of the immune system. PLoS ONE 5 (4), e9862 (2010).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with alphafold 3. Nature 630 (8016), 1–3 (2024).

Abraham, M. J. et al. High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1, 19–25 (2015).

Masirika, L. M. et al. Ongoing Mpox outbreak in Kamituga, South Kivu Province, associated with Monkeypox virus of a novel clade I sub-lineage, Democratic Republic of the congo, 2024. Euro Surveill. 29 (11), 2400106 (2024).

Hatmal, M. M. et al. Comprehensive literature review of Monkeypox. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 11 (1), 2600–2631 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51 (D1), 384–388 (2023).

Geanes, E. S. et al. Cross-reactive antibodies elicited to conserved epitopes on SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein after infection and vaccination. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 6496 (2022).

Quandt, J. et al. Omicron BA. 1 breakthrough infection drives cross-variant neutralization and memory B cell formation against conserved epitopes. Sci. Immunol. 7 (75), 2427 (2022).

Mosa, A. I. et al. Polyvalent immunization elicits a synergistic broadly neutralizing immune response to hypervariable region 1 variants of hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120 (24), e2220294120 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support by the Brazilian agencies. This study was supported in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) (Grant/Award Number: 001), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (Grant/Award Number: BPD-00626-22), and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) (Grant/Award Number: BPD-00626-22 and APQ-01297-23). We also thank the research conducted with the support of HPC resources provided by the Information Technology Superintendency of the University of São Paulo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.P.D.A. conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation and writing—original draft. E.N.S, S.M.D.A. and P.P.C. data curation, formal analysis, investigation and methodology. L.A.D.A. conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, supervision, validation, visualization and writing—original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Araújo, L.P., Silva, E.N., de Alencar, S.M. et al. Multivalent vaccine candidate from conserved immunogenic peptides in entry or exit proteins of Orthopoxvirus genus. Sci Rep 15, 12503 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96755-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96755-4