Abstract

TERT promoter mutation is associated with poor prognosis in differentiated thyroid carcinoma, with US features varying by mutation status. However, this correlation in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) is understudied. We investigated the association between clinicopathological characteristics and US features of ATC with TERT mutation status and prognosis. From November 1994 to May 2022, 58 ATC nodules from 58 patients were analyzed. Two radiologists retrospectively reviewed US features based on the revised K-TIRADS and ACR-TIRADS. Of all 58 ATC nodules, 32 nodules were tested for TERT promoter mutation and detected in 11. TERT promoter-mutated ATC was larger than TERT wild-type ATC (p = 0.032); however, no other differences were observed. ATC with survival period of less than 12 months were more likely to have lymph node metastasis (p = 0.012) or distant metastasis at diagnosis (p < 0.001), larger size on US (p = 0.005), and suspicion for gross extrathyroidal extension on US (p = 0.04) compared to ATC with survival period of 12 months or more. Advanced disease at diagnosis was a critical factor associated with 1-year survival in patients with ATC, whereas the TERT promoter mutation status was not.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) accounts for only 1%–2% of all thyroid cancers but is responsible for over 50% of thyroid cancer-related deaths1,2. In a recent single-institution study on a cohort spanning the past 20 years, changes in management have been reported to increase the median overall survival (OS) of ATC patients, with the median OS for the entire cohort reaching 9.5 months3. However, despite this improvement, ATC remains one of the most aggressive and fatal solid tumors, with disease-specific mortality approaching 100%1,3. Studies have identified several factors associated with ATC prognosis, including age, sex, tumor size, resectability, extent of disease, gross residual disease after surgery, and the presence of distant metastasis1,4,5,6,7,8.

Recently, the identification of diagnostic and prognostic molecular markers has led to improved risk stratification and personalized management of patients with thyroid cancer9,10. Among these markers, the BRAF mutation is one of the most common alterations and serves as a key oncogenic driver in thyroid cancer, observed in approximately 27.3%–87.1% of all papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC)11. Previous studies have demonstrated that the BRAF V600E mutation was associated with high-risk clinicopathological features12,13. However, other studies have presented conflicting evidence, with some reporting no significant correlation between the BRAF mutation and prognosis14,15,16. ATCs are frequently characterized by additional molecular alterations, including telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutation. TERT promoter mutation is highly prevalent in advanced thyroid cancers, with a collective prevalence of 11.3% in PTCs, 17.1% in follicular thyroid carcinomas (FTCs), and 40.1% in ATCs17. TERT promoter mutation is associated with aggressive tumor characteristics, increased recurrence, and higher mortality rates in PTC17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. The coexistence of BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations is known to significantly enhance the aggressiveness of PTC, particularly in terms of tumor recurrence and patient mortality7,17,20,25. Moreover, several studies have reported that TERT promoter mutations are also associated with worse survival outcomes in FTC, further highlighting their clinical significance beyond PTC18,19,22,23,24. However, studies have reported inconsistent results regarding the association between the TERT promoter mutation status and prognosis in ATC. Some studies have reported that TERT promoter mutation is associated with frequent distant metastasis or worse overall survival7,8,26, while others have shown no association between TERT promoter mutations and the prognosis of ATC19,27,28,29.

Despite the characteristic of a rapidly enlarging thyroid mass in ATC, ultrasonography (US) remains one of the fundamental diagnostic modalities. Several studies have investigated the relationship between the US features of DTCs and patient prognosis30,31,32,33,34,35. In terms of TERT promoter mutation, research indicates that TERT-mutated PTCs are more likely to exhibit malignant-like US features34,35. Another recent study indicates that FTCs with TERT promoter mutations are more frequently categorized as high suspicion according to Korean Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (K-TIRADS) and American College of Radiology-TIRADS (ACR-TIRADS) criteria31. However, due to the rarity of ATC, it remains uncertain whether US findings of ATC vary based on the TERT promoter mutation status and how these findings correlate with patient prognosis. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the association between the clinicopathological characteristics and US features of ATC with the TERT promoter mutation status and patient survival.

Materials and methods

Study population

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (IRB No. SMC 2024-07-031), which waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study. In addition, all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

The 54 patients included in this study were part of a previous study, which focused on the clinicopathological characteristics and survival between symptomatic and asymptomatic ATC36. The current study focuses on the US features of ATC, the status of TERT promotion mutation, and the survival period. A total of 120 patients with ATC registered at our hospital between November 1994 and May 2022 were identified. Among them, 37 patients without initial US images, eight patients with recurrence, five patients lost to follow-up, four patients without pathologic review at our institution, four patients with anaplastic foci found only in the lymph nodes, and four patients with US images inappropriate for analysis were excluded. Finally, 58 patients were included in the study. Two of the 58 patients exhibited two ATC nodules; in such cases, only the larger nodule was included in the analysis. A flowchart of the study population is shown in Fig. 1.

Clinicopathological data

Clinicopathological data were collected through a review of electronic medical records. The data included patient age, sex, TERT promoter mutation status, BRAF mutation status, presence of pathological extrathyroidal extension (ETE) if surgery was performed, lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis, distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and the survival period. The survival period was defined as the time interval between diagnosis and death for deceased patients or between diagnosis and the most recent hospital visit for living patients. TERT promoter mutation and BRAF V600E mutation statuses were analyzed using either next-generation sequencing (NGS) or Sanger sequencing. The details of mutation analyses are described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods, Tables S1, and S2.

US examinations and US image analysis

All thyroid US examinations were performed using a 7–15 MHz linear array transducer with HDI 3000 or 5000 (Philips Healthcare), a 5–12 MHz linear array transducer with iU22 (Philips Healthcare), or a Logiq 700 scanner (GE Healthcare). Examinations were conducted by one of 53 radiologists (including six faculty members and 47 fellows) with 1–19 years of experience in thyroid imaging. Two radiologists (S.Y.H. and H.K.) retrospectively reviewed the US images and resolved any discrepancies through consensus. The radiologists were blinded to the clinicopathological characteristics of the patients during the analysis.

Tumor size on US was measured as the maximum diameter on transverse or longitudinal grayscale images. Following the revised K-TIRADS37, ATC nodules were evaluated based on following criteria: (1) composition (purely cystic, predominantly cystic, predominantly solid, or solid), (2) echogenicity (hyperechoic, isoechoic, mild hypoechoic, or marked hypoechoic), (3) margin (smooth, ill-defined, or irregular), (4) echogenic foci (punctate echogenic foci, macrocalcification, rim or peripheral calcification, or intracystic echogenic foci with comet tail artifact), (5) orientation (parallel or non-parallel). Additional features assessed included lobulation (defined as rounded protruding areas where the base measures 2.5 mm or more)38 and heterogeneity (defined as the presence of two distinct echogenic regions within the solid part). Thyroid nodules were classified into five categories in the final K-TIRADS assessment: category 1, no nodule; category 2, benign nodule (isoechoic/hyperechoic spongiform, partially cystic nodule with intracystic echogenic foci and comet tail artifact, or purely cystic); category 3, low-suspicion nodule (partially cystic or isoechoic/hyperechoic nodule without any of the three suspicious US features such as punctate echogenic foci, non-parallel orientation, and irregular margin); category 4, intermediate suspicion nodule (solid hypoechoic nodule without any of the three suspicious US features, partially cystic or isoechoic/hyperechoic nodule with any of the three suspicious US features, or entirely calcified nodules); and category 5, high suspicion nodule (solid hypoechoic nodule with any of the three suspicious US features). The ACR-TIRADS US lexicon is summarized in Table S339.

Statistical analysis

All categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were analyzed using the Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Advanced disease was defined as positive if two or more of the following four criteria were met: presence of lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis, presence of distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis, nodule size larger than 4 cm on US, and suspicion of gross ETE on US.

We performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis to identify the factors associated with a survival period of < 12 months. A logistic regression model was run for rare events using Firth’s penalized maximum likelihood estimation method. In multivariable analysis, we included variables with p values less than 0.1 in the univariable analysis. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. All statistical analysis were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p value < 0.05.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics and US features of overall study population

We included 58 ATC nodules from 58 patients (mean age ± standard deviation, 66.74 ± 12.44 years). Females were more common (36/58, 62.07%) than men. BRAF mutation testing was performed in 38 (65.51%) of the 58 ATC nodules and was present in 18 (47.37%) of the 38 nodules. Thirty-nine (67.24%) ATC nodules underwent surgery, with pathological ETE identified in 31 (79.49%) of the 39 cases. Forty-one (70.69%) of the total 58 ATC nodules had lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and 30 (51.72%) of the total 58 ATC nodules had distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. The overall median survival period of the total included patients was 7.12 months (interquartile range, 2.67–28.53).

The mean size of the ATC nodules on US was 4.69 ± 1.65 cm. The majority of ATC nodules were solid (42/58, 72.41%), markedly hypoechoic (44/58, 75.86%), had a parallel orientation (53/58, 91.38%), had calcifications (47/58, 81.03%), were heterogeneous (49/58, 84.48%), and were lobulated (38/58, 65.52%). Twenty-eight (48.28%) of the 58 ATC nodules had smooth margins, 27 (46.55%) had irregular margins, and 3 (5.17%) had ill-defined margins. Of the 58 ATC nodules, 48 (82.76%) were suspected of gross ETE on US. Thirty-two (55.17%) ATC nodules were classified as K-TIRADS 5 (high suspicion) and 49 (84.48%) as ACR TI-RADS 5 (highly suspicious).

At the time of diagnosis, 50 (86.21%) of the 58 ATC nodules met the criteria for advanced disease, defined as meeting two or more of the following four conditions: lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis, distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis, nodule size greater than 4 cm on US, and suspicion of gross ETE on US.

Clinicopathological characteristics and US features of ATC according to the TERT promoter mutation status

Of the 58 ATC nodules, 32 were tested for TERT promoter mutation: 11 had mutation while 21 did not. Age, sex, BRAF mutation status, presence of pathological ETE, lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis, distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and survival period showed no significant differences between the groups (p > 0.05) (Table 1). Kaplan–Meier analysis (Fig. 2) showed no significant difference in survival in relation to TERT promoter mutation status (log-rank p = 0.409).

ATC nodules with TERT promoter mutation were significantly larger on US than those without the mutation (5.47 ± 1.12 cm vs. 4.14 ± 1.77 cm, p = 0.032), while other US features—composition, echogenicity, margin, orientation, echogenic foci, heterogeneity, lobulation, gross ETE, K-TIRADS, and ACR TI-RADS—showed no significant differences (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Although all 11 ATC nodules with TERT promoter mutation showed advanced disease at the time of diagnosis, they did not statistically differ from the nodules without TERT promoter mutation (100.00% vs. 76.19%, p = 0.138).

Clinicopathological characteristics and US features of ATC according to survival period

The clinicopathological characteristics of ATC nodules based on the survival period (< 12 months vs. ≥ 12 months) were assessed (Table 2). Patients with a survival period of less than 12 months were more likely to have lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis (82.86% vs. 52.17%, p = 0.012) and distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis (74.29% vs. 17.39%, p < 0.001). Other factors such as age, sex, TERT promoter mutation status, BRAF mutation status, and pathological ETE did not differ significantly between the two survival groups (p > 0.05).

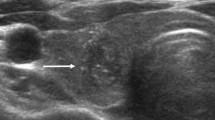

When comparing US features based on survival period, nodules in patients with a survival period of less than 12 months were larger (5.17 ± 1.49 cm vs. 3.95 ± 1.63 cm, p = 0.005) and more likely to be suspicious for gross ETE on US (91.43% vs. 69.57%, p = 0.04) (Table 2, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Other US features, such as composition, echogenicity, margin, orientation, echogenic foci, heterogeneity, lobulation, K-TIRADS, and ACR TI-RADS, did not significantly differ between the two groups (p > 0.05).

A 78-year-old woman diagnosed with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, confirmed to be negative for TERT promoter mutation. (A) The transverse US image displays a 5.9 cm lobulated, predominantly solid, markedly hypoechoic nodule in the left thyroid gland, exhibiting parallel orientation and suspicious gross extrathyroidal extension (ETE) (arrows). (B) Multiple suspicious cystic metastatic lymph nodes are evident in both bilateral necks (arrows). (C) The axial contrast-enhanced CT image reveals a large necrotic mass in the left thyroid gland that is heterogeneously enhancing, with gross ETE and direct invasion of the adjacent trachea, esophagus, and anterior strap muscle (arrows). (D) The PET-CT image illustrates uptake in the thoracic spine (arrow), suggestive of bone metastasis. The patient died 1.57 months following diagnosis. CT, computed tomography; PET-CT, positron emission tomography-computed tomography; TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase; US, ultrasonography.

A 56-year-old woman diagnosed with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, confirmed to be negative for TERT promoter mutation. (A, B) The transverse and longitudinal US images reveal a 1.8 cm irregular, heterogeneous hypoechoic nodule with punctate echogenic foci in the right thyroid gland (arrows). The nodule is intrathyroidally located, and gross extrathyroidal extension (ETE) was not suspected on US. (C) Multiple metastatic lymph nodes are observed in the ipsilateral neck (arrow). (D) The axial contrast-enhanced CT image demonstrates a low-density mass in the right thyroid gland without evidence of ETE (arrow). There was no indication of distant metastasis at diagnosis. A total thyroidectomy with central neck dissection and right lateral neck dissection was performed, which revealed no pathological ETE. The patient remains alive, with a survival period of 59.77 months from diagnosis to the most recent follow-up, without recurrence. CT, computed tomography; TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase; US, ultrasonography.

ATC nodules in patients with survival period of less than 12 months more frequently showed advanced disease at the time of diagnosis (97.14% vs. 69.57%, p = 0.005).

Factors associated with survival period less than 12 months in ATC

Univariable and multivariable analysis were performed to identify factors associated with a survival period of less than 12 months (Table 3). Univariable analysis revealed that lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis (odds ratio [OR], 4.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.33–14.72; p = 0.015), distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis (OR, 13.72; 95% CI 3.67–51.27; p < 0.001), larger nodule size on US (OR, 1.70; 95% CI 1.13–2.54; p = 0.01), suspicion of gross ETE on US (OR, 4.67; 95% CI 1.06–20.49; p = 0.041), and advanced disease (OR, 14.87; 95% CI 1.69–131.31; p = 0.015) were significantly associated with a survival period of less than 12 months.

Among the variables with p values less than 0.1 in the univariable analysis, only the “advanced disease” variable was included in the multivariable analysis instead of the four following variables (lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis, distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis, size on US, and suspicion of gross ETE on US) because those are incorporated in the ‘advanced disease’ variable. Advanced disease was the only significant factor associated with a survival period of less than 12 months in patients with ATC (OR, 12.68; 95% CI 1.40, 114.87; p = 0.024) (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, the TERT promoter mutation in ATC was associated with a larger tumor size but did not exhibit significant differences in other clinicopathological characteristics or US features compared to ATC without the mutation. Notably, ATC nodules in patients with a survival period of less than 12 months were more likely to be larger, suspicious for gross ETE on US, and to present with distant or lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis. However, the TERT promoter mutation status was not associated with a survival period of less than 12 months in patients with ATC. These findings highlight that advanced disease at the time of diagnosis may serve as a more critical predictor of shorter survival periods in patients with ATC compared to the TERT promoter mutation status.

Although numerous studies have shown that TERT promoter mutations are associated with poor prognosis in thyroid cancer, these findings are mostly derived from DTC18,19,20,24. However, research on the association of TERT promoter mutations with ATC is rare, likely due to the rarity of ATC itself, even though TERT promoter mutations are more prevalent in ATCs than in DTCs24,40,41. In our study, distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis was likely more frequent in TERT promoter-mutated ATC compared with TERT wild-type ATC; however, the difference was not statistically significant. Other findings, including pathological ETE, lymph node metastasis, and survival period, exhibited no significant differences between TERT promoter-mutated and wild-type ATC. A previous study showed that TERT promoter mutation was associated with distant metastasis in ATC; however, no association was found with lymph node metastasis and ETE of ATC8. In contrast, another study found that TERT promoter mutations in DTC were associated with distant metastasis; however, there was no such correlation in PDTC and ATC, which is consistent with the results of our study24. Regarding the survival period, several studies have shown conflicting results concerning the association between the TERT promoter mutation status and the survival of patients with ATC. Some studies indicate that TERT promoter-mutated ATC is associated with worse overall survival7,26, whereas others suggest that survival is not significantly influenced by the TERT promoter mutation status in ATC19,27,28,29. We did not find an association between TERT promoter mutation and prognosis-related factors other than nodule size, raising questions about the usefulness of testing for TERT promoter mutation in ATC. However, it is known that beyond a certain cutoff, an increase in cancer size is associated with a poorer prognosis42. While our study did not find statistically significant differences in other prognostic factors, the association between TERT promoter mutations and larger nodule size suggests that TERT promoter mutations may still contribute to tumor aggressiveness by driving increased tumor size, which then might affect prognosis. Therefore, TERT promoter mutations should not be regarded as completely unrelated to patient outcomes. The small sample size may have hindered our ability to draw definitive conclusions.

The four most common mutations in ATC are TP53 alterations, RAS mutations (H-K-N RAS), BRAF mutations (primarily V600E), and TERT promoter alterations (C228T and C250T), with TP53 alterations being the most frequent7,27,43,44. TP53 mutations cause protein inactivation, leading to the inhibition of apoptosis and uncontrolled cell cycle progression, which are very rare in DTC, supporting the notion that they occur as a late event in tumor dedifferentiation2. In our study, all six patients with TERT promoter mutations detected by NGS had accompanying mutations (Table S4). Three cases had three co-mutations, while the remaining three cases had two co-mutations. The most common co-mutation was TP53, found in four cases, followed by BRAF in three cases and RAS in two cases. The coexistence of BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations is known to significantly enhance the aggressiveness of PTC7,17,20,25, but studies on the association between other co-mutations and prognosis in ATC are lacking. Furthermore, a study analyzing 168 patients with PTC demonstrated that a high percentage of BRAF V600E alleles in PTC is associated with a poorer outcome45. This supports the idea that the prognostic relevance of genetic mutations may depend on the proportion of mutant alleles present. Although our small sample size limited the assessment of prognostic differences based on variant allele frequency (VAF) of TERT promoter mutation in ATC, future studies with a larger cohort may clarify whether VAF levels influence prognosis. In conclusion, in ATC, further research may be needed to investigate not only the presence of TERT promoter mutations alone but also the synergistic effects of co-mutations and factors such as VAF in relation to prognosis.

Owing to the rarity of the disease, only a few studies have evaluated the US findings of ATC. Previous studies showed that typical malignant-favoring US features such as uncircumscribed margins and irregular shapes are the common US features of ATC46,47,48. In our study, 91.38% ATC nodules showed parallel orientation, which is not a typical malignant-favoring US feature37,39. The mechanism of the “taller-than-wide sign” is no or minimal compressibility of a thyroid mass by the US probe, which occurs more frequently in malignant masses than in benign masses49,50. In cases of large ATC, the tumor often replaces nearly an entire thyroid lobe; since the thyroid itself is generally wider than it is tall, lesions that replace the entire thyroid might appear parallel in US images. Regarding the margin, nodules with smooth margins (48.28%) were slightly more common than those with irregular margins (46.55%) in our study. Circumscribed margins are usually benign-favoring US features, but some high-grade or rapidly growing tumors, such as those in breast cancer, can also present with circumscribed margins51. Similarly, rapidly growing ATC might present smooth but expanding and pushing border margins in some areas. On the other hand, US may be limited in comprehensively assessing the overall margins of large ATCs compared to CT. Therefore, some circumscribed margins may be evaluated using US, whereas irregular and infiltrative margins on the other side of the tumor may not be adequately assessed. This limitation is due to the large size of ATCs and the restricted field of view of US. This might explain our finding that only 55.17% of ATC nodules were classified as 5 (high suspicion) based on the K-TIRADS, whereas 84.48% were classified as 5 (highly suspicious) using the ACR TI-RADS. The ACR TI-RADS assigns a score of 3 if there is ETE regardless of the nodule margin, whereas nodules with smooth margins are more likely to be classified as K-TIRADS 4 (intermediate suspicion). Therefore, when evaluating large ATCs that do not fit within a single US screen, closely examining the entire lesion margin is crucial.

Among the US features of ATC, larger size and suspicion of gross ETE on US were common in ATCs with a survival period of less than 12 months. Even in the presence of distant disease, achieving local control can improve short-term survival rates, as the rapid local progression of ATC, often leading to suffocation, is the most frequent cause of death in these patients1,2. ATC with a larger size and obvious ETE on US, revealing direct invasion into the adjacent trachea or critical perithyroidal structures, may be prone to an uncontrollable disease state, resulting in a shorter survival period. In contrast, an intrathyroidal ATC nodule on US, which lacks the US features of gross ETE, might be expected to show a longer survival period, in line with a previous study4,6.

This study has several limitations. First, the study population was small, reflecting the rarity of ATC. Second, because the data were collected retrospectively over an extended period, advances in treatment that could affect patient survival were not considered. Third, not all patients underwent surgery, resulting in the absence of pathological ETE data for 19 patients. Additionally, not all patients were tested for BRAF or TERT promoter mutations, leaving 20 and 26 cases, respectively, without this information. Among the 26 cases in which TERT promoter mutation testing was not performed, 7 were from the 39 surgical cases.

In conclusion, TERT promoter mutations were not associated with pathological ETE, the presence of lymph node or distant metastasis at diagnosis, or the survival period in patients with ATC. Moreover, US features, apart from size, did not significantly differ according to TERT promoter mutation status, in contrast to findings in other DTCs. However, larger nodule size, suspicion of gross ETE on US, and the presence of lymph node or distant metastasis at diagnosis were critical factors associated with 1-year survival in patients with ATC. These findings emphasize that the extent of advanced disease at the time of diagnosis may be more closely associated with survival outcomes than TERT promoter mutation in patients with ATC.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Are, C. & Shaha, A. R. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: Biology, pathogenesis, prognostic factors, and treatment approaches. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 13, 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1245/aso.2006.05.042 (2006).

Molinaro, E. et al. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: From clinicopathology to genetics and advanced therapies. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 13, 644–660. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2017.76 (2017).

Maniakas, A. et al. Evaluation of overall survival in patients with anaplastic thyroid Carcinoma, 2000–2019. JAMA Oncol. 6, 1397–1404. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3362 (2020).

Kebebew, E., Greenspan, F. S., Clark, O. H., Woeber, K. A. & McMillan, A. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Cancer 103, 1330–1335. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20936 (2005).

Smallridge, R. C. et al. American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid 22, 1104–1139. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2012.0302 (2012).

Kim, T. Y. et al. Prognostic factors for Korean patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Head Neck 29, 765–772. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20578 (2007).

Xu, B. et al. Dissecting anaplastic thyroid Carcinoma: A comprehensive clinical, histologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 360 cases. Thyroid 30, 1505–1517. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2020.0086 (2020).

Shi, X. et al. Association of TERT promoter mutation 1,295,228 C> T with BRAF V600E mutation, older patient age, and distant metastasis in anaplastic thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100, E632–E637 (2015).

Xing, M., Haugen, B. R. & Schlumberger, M. Progress in molecular-based management of differentiated thyroid cancer. Lancet 381, 1058–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60109-9 (2013).

Smallridge, R. C., Marlow, L. A. & Copland, J. A. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: Molecular pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 16, 17–44. https://doi.org/10.1677/erc-08-0154 (2009).

Li, C., Lee, K. C., Schneider, E. B. & Zeiger, M. A. BRAFV600E mutation and its association with clinicopathological features of papillary thyroid cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, 4559–4570. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-2104 (2012).

Xing, M. et al. Association between BRAF V600E mutation and mortality in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. JAMA 309, 1493–1501. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.3190 (2013).

Elisei, R. et al. The BRAF(V600E) mutation is an independent, poor prognostic factor for the outcome of patients with low-risk intrathyroid papillary thyroid carcinoma: Single-institution results from a large cohort study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, 4390–4398. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-1775 (2012).

Russo, M. et al. The BRAF(V600E) mutation influences the short- and medium-term outcomes of classic papillary thyroid cancer, but is not an independent predictor of unfavorable outcome. Thyroid 24, 1267–1274. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2013.0675 (2014).

Gouveia, C. et al. Lack of association of BRAF mutation with negative prognostic indicators in papillary thyroid carcinoma: the University of California, San Francisco, experience. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 139, 1164–1170. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4501 (2013).

Lai, H.-F. et al. BRAF V600E mutation lacks association with poorer clinical prognosis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 31, 3495–3501. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-024-14935-4 (2024).

Liu, R. & Xing, M. TERT promoter mutations in thyroid cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 23, R143–R155. https://doi.org/10.1530/erc-15-0533 (2016).

Liu, T. et al. The age- and shorter telomere-dependent TERT promoter mutation in follicular thyroid cell-derived carcinomas. Oncogene 33, 4978–4984. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2013.446 (2014).

Kim, T. H. et al. TERT promoter mutations and long-term survival in patients with thyroid cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 23, 813–823. https://doi.org/10.1530/erc-16-0219 (2016).

Lee, S. E. et al. Prognostic significance of TERT promoter mutations in papillary thyroid carcinomas in a BRAF(V600E) mutation-prevalent population. Thyroid 26, 901–910. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2015.0488 (2016).

Gandolfi, G. et al. TERT promoter mutations are associated with distant metastases in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 172, 403–413 (2015).

Park, H. et al. Molecular classification of follicular thyroid carcinoma based on TERT promoter mutations. Mod. Pathol. 35, 186–192 (2022).

Muzza, M. et al. Telomerase in differentiated thyroid cancer: promoter mutations, expression and localization. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 399, 288–295 (2015).

Melo, M. et al. TERT promoter mutations are a major indicator of poor outcome in differentiated thyroid carcinomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, E754–E765. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-3734 (2014).

Xing, M. et al. BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations cooperatively identify the most aggressive papillary thyroid cancer with highest recurrence. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 2718–2726. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2014.55.5094 (2014).

Duan, H. et al. Mutational profiling of poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma by the use of targeted next-generation sequencing. Histopathology 75, 890–899. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13942 (2019).

Landa, I. et al. Genomic and transcriptomic hallmarks of poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 1052–1066. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci85271 (2016).

Lai, W. A., Liu, C. Y., Lin, S. Y., Chen, C. C. & Hang, J. F. Characterization of driver mutations in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma identifies RAS and PIK3CA mutations as negative survival predictors. Cancers 12, 1973. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12071973 (2020).

Wang, J. R. et al. Impact of somatic mutations on survival outcomes in patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. JCO Precis Oncol. 6, e2100504. https://doi.org/10.1200/po.21.00504 (2022).

Rhee, S. J. et al. Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: distinct biologic behavior based on ultrasonographic features. Thyroid 24, 683–688. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2013.0351 (2014).

Kim, M. K. et al. Association of ultrasonography features of follicular thyroid carcinoma with tumor invasiveness and prognosis based on WHO classification and TERT promoter mutation. Korean J. Radiol. 25, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2023.0461 (2024).

Kim, S. Y., Kwak, J. Y., Kim, E. K., Yoon, J. H. & Moon, H. J. Association of preoperative US features and recurrence in patients with classic papillary thyroid carcinoma. Radiology 277, 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2015142470 (2015).

Nam, S. Y. et al. Preoperative ultrasonographic features of papillary thyroid carcinoma predict biological behavior. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98, 1476–1482. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-4072 (2013).

Kim, T. H. et al. Ultrasonographic prediction of highly aggressive telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter-mutated papillary thyroid cancer. Endocrine 57, 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-017-1340-3 (2017).

Shi, H. et al. Suspicious ultrasound and clinicopathological features of papillary thyroid carcinoma predict the status of TERT promoter. Endocrine 68, 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-020-02214-7 (2020).

Cho, S. et al. Comparison of clinicopathological characteristics and survival between symptomatic and asymptomatic anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 13, 3264 (2023).

Ha, E. J. et al. 2021 Korean thyroid imaging reporting and data system and imaging-based management of thyroid nodules: Korean society of thyroid radiology consensus statement and recommendations. Korean J. Radiol. 22, 2094–2123. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2021.0713 (2021).

Haug, L. P., Dahiya, N., Young, S. W. & Patel, M. D. Thyroid nodule margin assessment using ACR TI-RADS: Adding points for macrolobulation impairs performance. J. Ultrasound. Med. 42, 409–415. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.16034 (2023).

Tessler, F. N. et al. ACR thyroid imaging, reporting and data system (TI-RADS): White paper of the ACR TI-RADS committee. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 14, 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2017.01.046 (2017).

Landa, I. et al. Frequent somatic TERT promoter mutations in thyroid cancer: Higher prevalence in advanced forms of the disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98, E1562-1566. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-2383 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Highly prevalent TERT promoter mutations in aggressive thyroid cancers. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 20, 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1530/erc-13-0210 (2013).

Nguyen, X. V., Roy Choudhury, K., Tessler, F. N. & Hoang, J. K. Effect of tumor size on risk of metastatic disease and survival for thyroid cancer: Implications for biopsy guidelines. Thyroid 28, 295–300 (2018).

Wang, J. R. et al. Impact of somatic mutations on survival outcomes in patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. JCO Precis. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/po.21.00504 (2022).

Bonhomme, B. et al. Molecular pathology of anaplastic thyroid carcinomas: A retrospective study of 144 cases. Thyroid 27, 682–692. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2016.0254 (2017).

Guerra, A. et al. A high percentage of BRAFV600E alleles in papillary thyroid carcinoma predicts a poorer outcome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, 2333–2340 (2012).

Hahn, S. Y. & Shin, J. H. Description and comparison of the sonographic characteristics of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. J. Ultrasound Med. 35, 1873–1879. https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.15.09058 (2016).

Gu, L. S. et al. Comparison of sonographic characteristics of primary thyroid lymphoma and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. J. Thorac. Dis. 9, 4774–4784. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2017.09.48 (2017).

Suh, H. J., Moon, H. J., Kwak, J. Y., Choi, J. S. & Kim, E.-K. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: Ultrasonographic findings and the role of ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. Yonsei Med. J. 54, 1400–1406 (2013).

Yoon, S. J. et al. “Taller-than-wide sign” of thyroid malignancy: Comparison between ultrasound and CT. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 194, W420-424. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.09.3376 (2010).

Seo, Y. L. et al. Compressibility of thyroid masses: A sonographic sign differentiating benign from malignant lesions?. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 198, 434–438. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.11.6446 (2012).

Kettler, M. D. in Breast Imaging (eds Christoph I. Lee et al.) 0 (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K. and S.Y.H. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared Figs. 1–4. T.H.K. and Y.L.O. curated the data and performed the formal analysis. G.P. conducted the statistical analysis and validation. M.K.K. and J.H.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (IRB No. SMC 2024-07-031), which waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Park, G., Kim, M.K. et al. Prognostic significance of clinicopathological and ultrasonographic features in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma beyond TERT promoter mutation. Sci Rep 15, 11736 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96774-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96774-1