Abstract

Flood vulnerability mapping has significantly progressed with the advent of Machine Learning (ML), bringing greater certainty to predictions. However, conventional supervised ML techniques may not be feasible in regions where recorded flood inventory data is scarce. This study introduces a novel deep learning approach using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-led Autoencoder to assess flood vulnerability under such conditions. The methodology utilizes eleven causative factors, represented as geospatial layers, to characterize the regional environment. These layers are processed using CNN Autoencoder and K-means clustering to produce a flood risk zonation map for the upper and middle basins of the Damodar River. The autoencoder’s reconstruction performance is evaluated using metrics Mean Squared Error (MSE), precision, recall, and accuracy apart from cluster-based indices to evaluate its classification ability. The resulting map shows that 92% of the study area is safe, while less than 8% faces moderate to very high flood risk, aligning with historical patterns and validation analysis. The study highlights the strong impact of Drainage Density on model outcomes, while certain factors like Aspect introduce noise. These findings provide valuable insights into flood vulnerability, even in data-scarce regions, aiding proactive mitigation strategies for future flood events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Floods worldwide have had a devastating impact throughout recorded history, affecting economic, social, and environmental spheres. These events occur due to inundation from an adjacent water body or rapid accumulation of excessive rainfall within a short span of time leading to destruction across the spheres mentioned1.Floods can be broadly classified into flash floods, River floods, and Coastal floods. Inland basins often grapple with flash and river flood types. A river flood is an overflow-led disaster often caused by intense rainfall in the immediate vicinity or excess rainfall in upstream areas, leading to flooding downstream. Flash floods, a form of riverine flooding, occur when an overwhelming volume of water is rapidly released within a short timeframe, often between two to five hours following intense rainfall. These floods are marked by a sudden surge in water velocity, leading to severe damage to life and property2. While river-induced floods can cause widespread damage in their floodplains, high rainfall even in micro watersheds in the lower mountain slopes or plateau edges causes flash floods3.

Tropical regions are particularly susceptible to various hydrological hazards, with tropical floods being among the most devastating4. Located in a tropical geographical setting, India ranks second in global flood vulnerability5. At the macro level in India, it is relatively lower in northern India and the Western Ghats, while the Kosi, Gandak, and Damodar sub-basins have the highest vulnerability6. Flood vulnerability emanates from relative positioning with respect to the surrounding area, type of land use, control measures taken, if any, and the various water sources the region possesses. So, the first crucial step in managing flood disasters is conducting a vulnerability assessment.

Vulnerability maps act as the first line of defense in the process of Disaster management of floods by ensuring preparedness. They help assess the likelihood of flooding in a region based on its geographic characteristics. Remote sensing offers the advantage of large-scale predictive control over flood risks, with minimal field inputs7. Machine learning (ML) has revolutionized flood disaster management, providing advanced tools for analyzing large datasets and identifying complex patterns8. In recent years, a trend of multidisciplinary approach to flood risk assessment integrating GIS and ML models has been extensively used9,10. ML algorithms, such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), support vector machines, decision trees, and deep learning networks, process huge data from multiple sources like satellite imagery, weather stations, and historical recorded data11. In the case of flood vulnerability mapping, various thematic maps of geographical and meteorological factors are processed and compared with past flood events12. Using past recorded data as a reference to training models is supervised learning in ML parlance. ANNs excel at modelling non-linear systems, facilitating accurate flood hazard assessment and zonation by integrating GIS and remote sensing data13. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), a subset of ANNs, are specialized in image data analysis and achieve high accuracy in tasks like facial and action recognition14.

Across the globe, often there is an undercount of small-scale extensive disasters such as localized flooding especially due to flash flooding15. This leads to a situation where many regions lack recorded data to perform vulnerability mapping through supervised methodologies mentioned in previous sections. The unavailability and absence of recorded data bring to the fore unsupervised learning algorithms, which identify natural groupings and simplify data, setting the stage for deeper insights through deep learning16.

Materials and methods

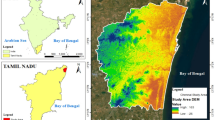

Study area

The Damodar River basin stretches across an extensive area of 23,370.98 km2, spanning majorly across Jharkhand and West Bengal17. It is one of the major river basins of eastern India and a key socioeconomic driver of the adjoining areas. The Damodar River travels through diverse topography characterized by the rugged plateau and the fertile alluvial plains. The Damodar River has tributaries such as Barakar, Konar, Tilaiya, and Katri18.

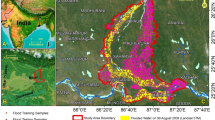

Damodar River Basin is one of India’s most analyzed basins for flood monitoring and risk categorization. Most works focus on the lower riparian part of the river19 whereas the upper and middle basin of the river is also known for floods, as shown in Fig. 1. The upper and middle basin is predominantly known for the economic activity of mining, especially coal. The mining sector is a frequent victim of surface water-led flooding and is relatively less scientifically investigated in this part of the world. Though not as rampant as the lower part, flooding impact is significant in the light of energy security of India. So, the present study’s focus is to analyze flood risk in this mining heartland of India, spanning 18,767.4 km2, as shown in Fig. 1.

Official inventory of floods for the study is absent but various reported news articles, which reveal only a few recorded instances, of floods in the study area spanning across the last 3 decades20,21,22,23,24. The reports have highlighted the severe impact of heavy rains in the Damodar basin of Jharkhand, including flooding of mines, road inundations in Dhanbad, power outages in Jamtara, and bridge collapses due to flash floods in Bokaro, West Bardhaman district in West Bengal which are shown as flood points in Fig. 1.

Data used

The Digital Elevation Model of the study area was obtained from the Bhuvan website for this study. Rainfall data is obtained from IMD25. The Geology and Geomorphology data are obtained from the Bhukosh website of the Geological Survey of India (GSI). The Land Use Land Cover (LULC) base image was obtained from the Sentinel-2 imagery. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery of Sentinel-1.

Methodology

Flood risk is dependent on the climate-morphometric properties of the area under study. The regional morphometric features are captured using GIS layers. DEM of the study area is used to derive most of the morphological factors like Elevation, Slope, Aspect, Drainage Density, TWI, and SPI. Apart from these, the Distance to the river, Geology, Geomorphology, and LULC layers complete the morphology of the basin under study. The climatic characteristics of floods are related to precipitation in the area, which in this case is the annual rainfall that occurs predominantly in the summer monsoon.

Image overlay analysis of GIS spatial layers is the fundamental technique employed for the risk categorization tasks of disasters26. However, the overlay analysis is done using tools like fuzzy logic, Principal component Analysis27,28 in GIS software have limited capability in understanding and deducing patterns from the layers unless the analysis is linked to a well-established empirical-physical model like RUSLE for soil erosion. As mentioned earlier, the present study area lacks scientifically documented flood history; the most appropriate approach is the unsupervised Deep learning algorithms, which do not need previous records as a training data mandate. The autoencoder (AE) approach was chosen for this study given the image-based input to be employed29.

AE is primarily a Deep Neural Network comprising an encoder and a decoder. The encoder compresses the input data, a high-dimensional one, into an abstract form while the decoder rebuilds this encoded information back to the original input. In this process, hidden layers are used to reduce or build back the dimensions sequentially and symmetrically. Such an arrangement is termed Stacked Autoencoder (SAE)30. In this study, a novel deep learning methodology integrating SAE with a K-means cluster-based classification for making regional flood vulnerability predictions was shown as process workflow in Fig. 2. The methodology can be divided into primarily two parts: (1) Use of SAE to sequentially compress the high dimensional flood input datasets into a low dimensional encoded and then sequentially decompress and reconstruct the code into the original dataset; (2) using a K-means based clustering to learn clusters data from the encoded form and predicting the clusters from the original data that are vulnerable to flood inundation based on these learnings.

Neurons in the hidden layers are typically activated using the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) function, favoured for its computational efficiency compared to the traditional sigmoid function. Additionally, ReLU helps mitigate the vanishing gradient problem during the backpropagation process in Deep Learning Neural Networks (DLNN), allowing for more effective training of deeper networks31. Backpropagation helps weight adjustments by reducing differences in the predicted and the observed data, which is calculated using the mean square cost function32. This study employs the Adam algorithm to train the deep neural network model for flash flood spatial prediction. Adam’s adaptive learning rate adjustment for each parameter makes it ideal for optimizing deep learning models, boosting both speed and performance demonstrated by its rapid convergence rates and strong classification performance31.

Layers preparation

Elevation

Elevation plays a crucial role as a conditioning factor in flood dynamics, influencing both the likelihood and severity of flood events in a region33. Water flows naturally from higher to lower elevations due to gravity, making lower areas more prone to flooding as they accumulate runoff from higher regions. Elevated areas, with their steeper slopes, experience faster runoff and reduced infiltration, often leading to flash floods, especially in mountainous regions34. Additionally, higher elevations often receive more rainfall due to the orographic effect, further heightening flood risk in these areas. A filled DEM35 is used as an Elevation layer that provides insights into height above the mean sea level of the study area, as shown in Fig. 1.

Slope

The elevation difference influences the energy of flowing water, where steeper gradients result in more destructive floods due to increased speed and force, causing significant erosion and damage36. An important derivative of elevation data is the slope which influences the energy of water flow. In areas with steep slopes, rainfall tends to run off quickly, reducing the time for infiltration into the soil. Steep slopes are particularly associated with flash floods, as the quick accumulation of runoff can lead to sudden and intense flooding events downslope. A filled DEM is used to derive the Slope of the study area in degrees as shown in the Fig. 3b

Aspect

It influences flooded water flow patterns, indirectly impacting flooding by affecting the soil moisture regime. Aspect gives the orientation of a pixel of all possible 8 directions, i.e., N, E, S, W, NE, SE, SW, NW. This key input indicates the direction of the flow of the flood and acts as a secondary effect on flooding37. For the present study area, the aspect is shown in Fig. 3a

Drainage density

Drainage density indicates the stream concentration in a given area and helps understand stream movement in hydrological models for varying scenarios. It depends on slope and surface morphology features like fractures and joints. It is derived from a basin or watershed, which itself is derived from the DEM of the study area, as shown in Fig. 3e. High river network density accelerates surface runoff, increasing flood risk, especially near drainage basins and rivers38. Areas with high drainage density are prone to flash floods, while regions with low density may experience prolonged, widespread flooding39.

Stream power index (SPI)

The Stream Power Index (SPI) is a measure used to predict the erosive power of flowing water in a landscape using slope and contributing area from flow accumulation40. It is derived from Eq. (1) below

where A is the catchment area and β is the slope in radians. In the present study, in Fig. 3g, high SPI values emerged in the high-order streams, indicating that high power to move material is concentrated near the river and its tributaries.

Topographic wetness index (TWI)

The Topographic Wetness Index (TWI) is a hydrological parameter that quantifies the spatial distribution of soil moisture and the potential for surface saturation41. It is obtained by generating flow accumulation and slope and inserting them in Eq. (2)

where α is the upside slope area and b is the slope gradient (in degrees). In general, the high TWI values and flooding are strongly correlated with each other42. High values of TWI correspond to areas favouring water accumulation and high runoff, which appropriately correspond to water bodies and basins in the region, as shown in Fig. 3f

Distance to river

Flooding tends to decrease as the distance from a river increases, indicating a negative correlation between flood risk and proximity to the river. The farther an area is from the river, the less likely it is to experience flooding43. It is basically a buffer zone created around the river, signifying a decreasing propensity of flood as one moves away from it. The ‘distance to river’ map for the study area is shown in Fig. 3d

Geology and geomorphology

A permeable formation helps absorb rainwater into the ground and, as a result, minimizes flood hazards. Similarly, an impermeable formation, such as the presence of igneous and metamorphic rocks increases the runoff rate, thereby by the flood risk44. The shapefile thus obtained contains a landscape divided based on geological timelines as shown in Fig. 3i. The Quaternary deposits are more permeable whereas the Archean and Permian formations are impermeable, while the rocks of Tertiary are intermediate45.

Geomorphology plays a critical role in determining how landscapes respond to hydrological events, particularly in the context of flooding46,47. The various geomorphic features, as shown in Fig. 3j, were assigned empirical indices based on previous works48,49,50.

Land use land cover

LULC dynamics significantly impact various hydrological processes, including infiltration, surface runoff, evaporation, and evapotranspiration51. ESRI’s AI-based LULC derived from Sentinel-2 imagery is used. Forests and vegetation enhance infiltration and reduce runoff, thereby lowering flood risk. In contrast, barren lands, riverbanks, impervious roads, and buildings increase runoff due to their low infiltration capacity52. In this study, in Fig. 3h, land use categories of urban, built-up and mining were categorized as single category as they possess the general absence of greenery and as a consequence are more vulnerable to flooding.

Rainfall

Monsoonal trough formed over the Indian subcontinent during the summer monsoon passes through much of the present study area leading to very high rainfall between the months of June and September in the range of 1100–1400 mm. The rainfall map shown in Fig. 3c, is generated using the IMD’s 0.25 × 0.25 grid rainfall dataset. Rainfall data between 1973 and 2023 was used. An increased precipitation rate significantly raises the likelihood of flooding in flood-prone areas, especially when combined with other contributing factors53.

Method

Pre-processing the layers

The Flood causative factors prepared as 11 GIS layers in the earlier section are stacked as bands of a single raster. The raster with eleven bands is given as input to the SAE. Before stacking them, the same resolution and the same ‘no data’ value for all the layers are ensured.

Autoencoder

The stacked raster is given as input converted into a 3-dimensional array with length, breadth, and layers representing them. However, the raster should be made compatible with CNN and memory limitations. So, the raster is divided into patches before feeding it to the CNN. The input data is split into 80 and 20, respectively, for the training and testing phases of Autoencoder. Before feeding it to the SAE the data in all layers is normalized to values between 0 and 1. As iterated earlier the CNN-led autoencoder has 2 parts: encoder and decoder as shown in Fig. 4. Each patch is read by the network batch wise for a specified number of epochs. Iterating for the given number of epochs, the 10-layered DLNN learns to encode the input data into a concise or smaller form, which is the first step of Autoencoder, i.e. Encoding. The encoder part thus creates a ‘Latent space’, in Fig. 2, where the original high dimensional data is represented in an abstract low dimensional form. The Decoder part learns to bring back the encoded ‘latent’ information to its original state as given in the input. The ‘Loss’ function and metrics calculate and provide the ability of the Autoencoder to recreate the original image from the encoded representation.

K-means clustering

The algorithm is trained using the Latent space created by the encoder. Different clusters from the encoded data are finally used to predict the clusters in the original data. The final output of 5 clusters64 of the flood vulnerability classes, which, upon interpretation, represent risk categories, is shown in Fig. 5. The coding part mentioned in this section is performed using Python programming language.

Results

Autoencoder metrics and evaluation

The ultimate architecture and criteria used are selected based on the trial-and-error method depending on the model’s performance in the testing phase. The Loss function of Mean Square error (MSE) was used to compute variation in predicted and actual values of pixels. Apart from that evaluation metrics accuracy, recall, and precision were used to understand the reconstruction ability of the autoencoder16,54. As can be inferred from Fig. 6a, the loss consistently declined over the epochs and stabilized at 0.052 for training data and 0.084 for validation data. Also, metrics accuracy, precision, and recall registered improvement over the epochal runs in Fig. 6b–d. Here, accuracy overall is lower, resulting from massive data with many classes. Recall values are also on the lower side, indicating the model’s tendency to avoid false positives. Precision in our study provides better insights into model performance, with true positive cases being dominant in 90% of the training data and 85% of the validation data. Overall, the performance of Autoencoder in regenerating the original image can be termed satisfactory from these metrics. The reconstruction closer to the original mirrors the efficacy of the model’s latent space, which is used to generate the ultimate flood zonation map. While these metrics evaluate overall AE’s performance, the latent space and its understanding of clusters from the input needs evaluation.

For Neural networks and especially Encoder of an AE, t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding (t-SNE)61 is used to understand the abstract or latent form of data. It is a non-linear dimensionality reduction technique designed for visualizing high-dimensional data in 2D or 3D, preserving local structures to reveal clusters and patterns. It measures pairwise similarities using a Gaussian distribution in high dimensions and a Student’s t-distribution in lower dimensions to address the crowding problem. By minimizing Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence through gradient descent, t-SNE captures complex, non-linear relationships, making it ideal for visualizing neural network embeddings, especially image features. Such t-SNE representation of the latent space in 2D is shown in Fig. 6e, enabling us to visualize cluster patterns recognised by the AE in the process.

While t-SNE is effective at visualizing clusters, it’s important to quantitatively evaluate how well the data has been clustered. Two widely used metrics are the Silhouette Score63 and the Davies-Bouldin Index62. The Silhouette Score measures how similar an object is to its own cluster compared to other clusters

where, for a data point i, a(i) is the Average distance from all other points in the same cluster and b(i) = Average distance to all points in the nearest neighboring cluster. It ranges from − 1 to 1: + 1 indicates that the data point is well matched to its cluster and poorly matched to neighboring clusters. − 1 suggests that the data point might be assigned to the wrong cluster. This model’s s(i) turned out to be 0.545 indicates that the clusters formed by the t-SNE visualization are well-separated, suggesting the encoder captured meaningful distinctions in the data.

The Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI) evaluates the compactness and separation of clusters. It is a ratio of intra-cluster distances to inter-cluster distances.

where, N is the Total number of clusters; Si is the Average intra-cluster distance (compactness) for cluster i; Mij is the Distance between the centroids of clusters i and j (separation); For each cluster i, you calculate the ratio of the sum of intra-cluster distances (Si + Sj) to the inter-cluster distance Mij with all other clusters j. The maximum of these ratios represents the worst-case scenario for cluster i. Lower values (< 1) suggest well-separated clusters. Higher values (> 1) indicate overlapping or poorly separated clusters. A DBI of 0.507, in our case, suggests the clusters are reasonably compact and well-separated, validating the encoder’s effectiveness in capturing meaningful data structure.

Flood vulnerability map

The patterns recognized based on input causative factors culminated into the final flood risk zonation map. The clustered dataset obtained has clear demarcations of flood risk zonation. Despite having 5 clusters as shown in Fig. 5, the region is primarily divided into 3 categories65 broadly.

-

Very high–high values: These areas likely have high flood vulnerability. The Southeastern region shows a lot of red, indicating a higher likelihood of flooding.

-

Moderate values: These areas have moderate flood vulnerability in yellow shade. These areas surround the high-risk zones.

-

Very low–low values: These regions are indicated in blue and light green shades. Spread across the western and central parts of the region.

Validation

A total of 10 known flood points over the span of three decades were shown in Fig. 1 and overlayed on the flood risk zonation map as shown in Fig. 7a. The flood points, except for an outlier, were consistent with the map generated. Based on the data availability, one of the floods that occurred in the region in the year 2021 was analysed to validate the Risk zonation map further. The region, as shown in Fig. 7b, is drained by the Barakar River, a tributary of Damodar. The IMD data25 indicates an unusual and erratic rain of 160 mm on October 30 of the year 2021 can be noticed in Fig. 7d. As covered by various news agencies, the district and surrounding areas witnessed the situation of flash floods leading to incidents of bridge collapse and damage to houses, as shown in Fig. 7c. The Sentinel-1 imagery, a Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) image enhanced for better visualization, indicates the overflow of the river at different areas, as shown in Fig. 7b via a before and after scenario. The flood intensity can be termed Moderate65 from the damage witnessed, and the area impacted is close to 500 m from the affected river. This bears evidence to the final risk map derived indicating the above area in the moderate category. Here it must be noticed that vulnerability emanating from all the factors employed in the study is such that the area witnessed moderate damage. This is consistent with the fact that the area falls in the middle basin of the overall Damodar drainage, where the elevation is close to 300 m above mean sea level; river flow is in a mature phase than low-lying plains near coasts, leading to overall moderate damage. Similarly, the high flood-vulnerable regions in the adjoining Bardhaman district of West Bengal are in consonance with the Flood Atlas map of West Bengal67, with recurring high-intensity floods in the last 3 decades. Historical flood locations helped validate the overall vulnerability of the study area, while this flood event analysis helped to validate the flood risk classification, further cementing the findings of this study.

Discussion

Floods cause a significant amount of damage not only economically but also environmentally and socially by devastating biodiversity and livelihoods, among others. Flood vulnerability maps help in predicting the areas that are likely to be flood-prone and, in turn, help plan mitigative and adaptive measures55. The present study aims to identify flood-vulnerable areas with sparse historically recorded data but often subjected to flooding. This situation is often the case in many areas worldwide, which calls for a rather unsupervised approach because supervised machine learning requires training with historical data. For this, a novel combination of Autoencoder and K-means clustering was used in this study. The primary result of this study was a flood vulnerability map of the study region.

The flood vulnerability map identifies the lower southeastern and eastern of the basin as prone to flooding. A histogram graph generated to indicate risk classes as a percentage area covered is shown in Fig. 8. More than 92% of the study area is labelled as Safe from flooding, whereas less than 8% of the area is under moderate to very high risk of flooding. These findings are also in line with earlier studies on flood vulnerability of the entire Damodar basin18. The actual flood data collected from various sources like literature, news clippings, and local surveys indicate that within the area studied, the areas of Dhanbad, Bokaro, Giridh, parts of Jamtara, and areas of Bardhaman in West Bengal have histories of flooding, as mentioned in the earlier section on the study area. These parts of the study area are categorized under moderate to very high flooding categories, in line with flooding history. Morgan and Dobson et al.56 report on mines and floods, a world wildlife fund (WWF) study, indicates mines in these parts are victims of floods. Also, the performance of the autoencoder in recreating the original image is satisfactory because the precision, accuracy, and recall values of the model improved, whereas the loss function was reduced close to zero by the end of epochs. Also, a positive Silhouette score of 0.545 and DBI of 0.507 indicate a good level of pattern recognition by AE.

The impact of each causation factor on reconstruction in SAE was calculated using Perturbating error or Reconstruction error, as shown in Fig. 9. It is calculated by removing one of the 11 layers of the input and running the autoencoder to calculate the loss with respect to the original input. The reconstruction error is high if removing the factor has a high impact on the outcome and hence is important in the learning process. As indicated in Fig. 9, Drainage Density has created a very high loss among all the factors, indicating its role in developing patterns by the encoder witnessed in the final outcome. The factors of Slope, Elevation, TWI, and LULC have relatively similar losses in their absence. Flood around the middle basin of Damodar can also be attributed to changing land use in the form of urbanization and mining activity, making the land more vulnerable, evident in LULC led loss being higher. However, the negative reconstruction error values for Aspect and Distance to the River indicate these factors are creating noise to the learning process, evident from their very nature of uniformity over the map. It is prudent to note the ‘Distance to River’ role in the model’s learning, indicating decreasing risk away from the river, but greater than 92% of the study area being classified as little to no risk, leading to it being in the slightly noise category. On the other hand, the aspect’s contribution to pattern recognition is minimal from the fact that it only indicates the direction of water flow from pixel to pixel. Hence, the huge negative perturbation (noise). The local hills or Monadnocks within the high-risk zone are clearly indicated in the very low category despite being closer to the flood-vulnerable areas, indicating the fact that elevation layer’s role in the learning. These findings are in harmony with Costache et al.57 where similar studies based on the upper and middle basin of a river stretch were analysed for flood risk using ANN. Also, the relative importance of factors obtained is similar to the previous studies that employed supervised learning to categorize flood risk58,59.

The presence of dams in vulnerable areas helps to mitigate floods downstream, which is one of their prime mottos. However, the vulnerability despite such measures emanates from erratic rainfall(as seen in validation), haphazard urbanization, dam siltation, and poor communication with respect to the release of dam water, often leading to these areas under higher vulnerability are indicated in recent works66.The vulnerable areas need attention that includes structural like maintaining the water level in the Dams of Maithon and Panchet appropriately, timely desiltation, planned urbanization and non-structural measures including Floodplain zonation, mapping, conservation, plantation and vegetation growth around floodplains, emergency response, and Disaster preparedness17,58.

Minor upgrades can be made to improve its relevance for a smaller study area, like the use of higher resolution images to decode vulnerability on lesser spread features like a single mine. Future scope includes using cross-comparison studies worldwide, ensemble deep learning techniques, and the use of socio-cultural and political factors in prediction. The study has a huge scope in applicability universally especially where the inventory data is scarce. Overall, the model suggested in this study could be a valuable tool in disaster preparedness with the right set of causative factors.

Conclusion

Floods in the upper and middle of the Damodar basin threaten not only people’s lives but also India’s energy security as the coal extracted around the Damodar River forms the bulk of raw material for Thermal power plants in different parts of the country. The important economic activity of the region, Mining, is spread along the river basin of Damodar. The upper and middle Damodar basin forms one of India’s important economic and energy powerhouses; preparation of vulnerability maps forms the crux of planning and decision-making for mitigative and adaptation measures. However, studies are often limited to the lower basin of the river. So, this study uses a novel combination of Autoencoder and K-means to predict flood-vulnerable regions. The map generated categorized the regions in the southeastern and eastern parts of the study area as prone to floods. These results agree with the known flood points in the study area. Consequently, the mines and cities of Dhanbad, Bokaro, Giridh, and Jamtara districts are under moderate flood threat whereas neighboring areas of Bardhaman district of West Bengal are under High flood vulnerability. Also, the model’s learning implied that Drainage Density as a causation factor played a bigger part in identifying vulnerability. Overall, the model is extremely useful in predicting flood-prone areas, especially where flood inventory is absent.

Data availability

The data of the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sheet, S., Banerjee, M., Karmakar, M., Mandal, D. & Ghosh, D. Evaluation of flood risk at the river reach scale using Shannon’s Entropy Model: a case study of the Damodar River. Saf. Extrem. Environ. 5, 91–107 (2023).

Ouma, Y. O. & Omai, L. Flood susceptibility mapping using Image-Based 2D-CNN Deep Learning: overview and case study application using multiparametric spatial data in Data-Scarce urban environments. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2023, 1–23 (2023).

Nones, M. & Guo, Y. Can sediments play a role in river flood risk mapping? Learning from selected European examples. GeoEx. 10, (2023).

Eccles, R., Zhang, H. & Hamilton, D. A review of the effects of climate change on riverine flooding in subtropical and tropical regions. J. Water Clim. Change. 10, 687–707 (2019).

Sarkar, D. & Mondal, P. Flood vulnerability mapping using frequency ratio (FR) model: a case study on Kulik river basin, Indo-Bangladesh Barind region. Appl. Water Sci. 10, (2019).

Vegad, U., Pokhrel, Y. & Mishra, V. Flood risk assessment for Indian sub-continental river basins. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 1107–1126 (2024).

Ighile, E. H., Shirakawa, H. & Tanikawa, H. Application of GIS and machine learning to predict flood areas in Nigeria. Sustainability 14, 5039 (2022).

Bui, D. T. et al. A novel deep learning neural network approach for predicting flash flood susceptibility: A case study at a high frequency tropical storm area. Sci. Total Environ. 701, 134413 (2020).

Chan, S. W., Abid, S. K., Sulaiman, N., Nazir, U. & Azam, K. A systematic review of the flood vulnerability using geographic information system. Heliyon 8, e09075 (2022).

Weday, M. A., Tabor, K. W. & Gemeda, D. O. Flood hazards and risk mapping using geospatial technologies in Jimma City, southwestern Ethiopia. Heliyon 9, e14617 (2023).

Pandey, M. et al. Flood Susceptibility modeling in a subtropical humid low-relief alluvial plain environment: application of novel ensemble Machine Learning approach. Front. Earth Sci. 9, (2021).

Zhao, G., Pang, B., Xu, Z., Peng, D. & Zuo, D. Urban flood susceptibility assessment based on convolutional neural networks. J. Hydrol. 590, 125235 (2020).

Bouramtane, T. et al. Multivariate analysis and machine learning approach for mapping the variability and vulnerability of urban flooding: the case of Tangier City, Morocco. Hydrology 8, 182 (2021).

Goymann, P., Herrling, D., Rausch, A. Institute for Software and Systems Engineering, & Clausthal University of Technology. In Flood Prediction through Artificial Neural Networks: A Case Study in Goslar, Lower Saxony. IARIA, 2019: The Eleventh International Conference on Adaptive and Self-Adaptive Systems and Applications. https://personales.upv.es/thinkmind/dl/conferences/adaptive/adaptive_2019/adaptive_2019_5_10_58005.pdf (2019).

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2022: Our World at Risk: Transforming Governance for a Resilient Future (UNDRR, 2022).

Bentivoglio, R., Isufi, E., Jonkman, S. N. & Taormina, R. Deep learning methods for flood mapping: a review of existing applications and future research directions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 4345–4378 (2022).

Ghosh, D., Sheet, S., Banerjee, M., Karmakar, M. & Mandal, M. Flood characteristics and dynamics of sediment environment during Anthropocene: experience of the lower Damodar river, India. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 8, (2022).

Surajit, B., Mobin, A. & Alisha, P. Multi-criteria analysis for flood risk assessment using remote sensing & GIS technique—a case study of Damodar River Basin. I-manager’s J. Future Eng. Technol. 14, 64 (2018).

Ghosh, S. Flood dynamics and its spatial prediction using open-channel hydraulics and hydrodynamic model in the dam-controlled river of India. J. Ecohydraul. 8, 171–191 (2023).

Ahmed, F. Floodwaters fill Dhanbad colliery, claim 10 lives, leaving scores trapped. India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/indiascope/story/19951015-floodwaters-fill-dhanbad-colliery-claim-10-lives-leaving-scores-trapped-807782-1995-10-14 (1995).

Rain & dam fury flood Bokaro. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/rain-dam-fury-flood-bokaro/cid/379649 (2012).

Dey, S. & Mishra, S. Monsoon fury unabated; flood-like situation in some districts. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/ranchi/monsoon-fury-unabated-flood-like-situation-in-some-districts/story-uIic5rpWKmk124JbD5NnzI.html (2017).

Choubey, P. Coal town bridge caves in after flash floods. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraphindia.com/jharkhand/coal-town-bridge-caves-in-after-flash-floods/cid/1833022 (2021).

Commuters wade through inundated road, dams water recede. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/ranchi/dhanbad-commuters-wade-through-inundated-road-dams-water-recede/articleshow/104118828.cms (2023).

Pai, D. S., Sridhar, L., Rajeevan, M., Sreejith, O. P., Satbhai, N. S. & Mukhopadhyay, B. Development of a new high spatial resolution (0.25° × 0.25°) long period (1901–2010) daily gridded rainfall data set over India and its comparison with existing data sets over the region. Mausam 65, 1–18 (2014).

Liu, J. et al. Hybrid models incorporating bivariate statistics and machine learning methods for flash flood susceptibility assessment based on remote sensing datasets. Remote Sens. 13, 4945 (2021).

Chang, L.-C., Liou, J.-Y. & Chang, F.-J. Spatial-temporal flood inundation nowcasts by fusing machine learning methods and principal component analysis. J. Hydrol. 612, 128086 (2022).

Carreau, J. & Guinot, V. A PCA spatial pattern based artificial neural network downscaling model for urban flood hazard assessment. Adv. Water Resour. 147, 103821 (2021).

Jagannathan, P., Rajkumar, S., Frnda, J., Divakarachari, P. B. & Subramani, P. Moving vehicle detection and classification using Gaussian mixture model and ensemble Deep learning technique. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 1–15 (2021).

Kao, I.-F., Liou, J.-Y., Lee, M.-H. & Chang, F.-J. Fusing stacked autoencoder and long short-term memory for regional multistep-ahead flood inundation forecasts. J. Hydrol. 598, 126371 (2021).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep Learning (MIT Press eBooks, 2016).

Stateczny, A., Praveena, H. D., Krishnappa, R. H., Chythanya, K. R. & Babysarojam, B. B. Optimized deep learning model for flood detection using satellite images. Remote Sens. 15, 5037 (2023).

Das, S. Geospatial mapping of flood susceptibility and hydro-geomorphic response to the floods in Ulhas basin, India. Remote Sens. Appl.: Soc. Environ. 14, 60–74 (2019).

Hagos, Y. G., Andualem, T. G., Yibeltal, M. & Mengie, M. A. Flood hazard assessment and mapping using GIS integrated with multi-criteria decision analysis in upper Awash River basin, Ethiopia. Appl. Water Sci. 12, (2022).

Sheet, S., Banerjee, M., Mandal, D. & Ghosh, D. Time traveling through the floodscape: assessing the spatial and temporal probability of floods and susceptibility zones in the Lower Damodar Basin. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196, (2024).

Costache, R. Flash-Flood Potential assessment in the upper and middle sector of Prahova river catchment (Romania). A comparative approach between four hybrid models. Sci. Total Environ. 659, 1115–1134 (2019).

Edamo, M. L., Bushira, K. & Ukumo, T. Y. Flood susceptibility mapping in the Bilate catchment, Ethiopia. H2Open J. 5, 691–712 (2022).

Swain, K. C., Singha, C. & Nayak, L. Flood susceptibility mapping through the GIS-AHP technique using the cloud. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. 9, 720 (2020).

Seleem, O., Heistermann, M. & Bronstert, A. Efficient hazard assessment for pluvial floods in urban environments: a benchmarking case study for the City of Berlin, Germany. Water 13, 2476 (2021).

Rudra, R. R. & Sarkar, S. K. Artificial neural network for flood susceptibility mapping in Bangladesh. Heliyon 9, e16459 (2023).

Kakwani, D., Asodariya, G., Kumari, A., Prasad, K. S. & Prasad, B. Assessment and evaluation of flood vulnerability of Chhota Udepur District, Gujarat, India using analytical hierarchy process: a case study. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 52, 2281–2292 (2024).

Winzeler, H. E. et al. Topographic Wetness Index as a proxy for soil moisture in a Hillslope catena: Flow algorithms and map Generalization. Land 11, 2018 (2022).

Khalid, R. & Khan, U. T. Flood susceptibility mapping using ANNs: a case study in model generalization and accuracy from Ontario, Canada. Geocarto Int. 39, (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Flood susceptibility mapping in Dingnan County (China) using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system with biogeography based optimization and imperialistic competitive algorithm. J. Environ. Manag. 247, 712–729 (2019).

Luu, C. et al. Flood-prone area mapping using machine learning techniques: a case study of Quang Binh province, Vietnam. Nat. Hazards 108, 3229–3251 (2021).

Chaturvedi, R. & Mishra, S. D. Geomorphic features and flood susceptibility zones: A study for Allahabad district, Uttar Pradesh, India, using remote sensing and GIS technique. Trans. Inst. Indian Geog. 37, 259–268 (2015).

Khosravi, K., Pourghasemi, H. R., Chapi, K. & Bahri, M. Flash flood susceptibility analysis and its mapping using different bivariate models in Iran: a comparison between Shannon’s entropy, statistical index, and weighting factor models. Environ. Monit. Assess. 188, (2016).

Chetia, L. & Paul, S. K. Spatial assessment of flood susceptibility in Assam, India: A comparative study of frequency ratio and Shannon’s entropy models. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 52, 343–358 (2024).

Sonmez, O. & Bizimana, H. Flood hazard risk evaluation using fuzzy logic and weightage based combination methods in Geographic Information System (GIS). Sci. Iran. 27, 517–528 (2018).

Paule-Mercado, M. A. et al. Influence of land development on stormwater runoff from a mixed land use and land cover catchment. Sci. Total Environ. 599–600, 2142–2155 (2017).

Parsian, S., Amani, M., Moghimi, A., Ghorbanian, A. & Mahdavi, S. Flood hazard mapping using fuzzy logic, analytical hierarchy process, and Multi-Source geospatial datasets. Remote Sens. 13, 4761 (2021).

Thiagarajan, K., Anandan, M. M., Stateczny, A., Divakarachari, P. B. & Lingappa, H. K. Satellite image classification using a hierarchical ensemble learning and correlation coefficient-based gravitational Search algorithm. Remote Sens. 13, 4351 (2021).

Ghosh, S. & Mistri, B. Geographic concerns on flood climate and flood hydrology in Monsoon-Dominated Damodar River Basin, eastern India. Geogr. J. 2015, 1–16 (2015).

Ali, M. H. M., Asmai, S. A., Abidin, Z. Z., Abas, Z. A. & Emran, N. A. Flood prediction using deep learning models. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 13, 972–981 (2022).

Saeed, M. et al. Flood hazard zonation using an artificial neural network model: a case study of Kabul River Basin, Pakistan. Sustainability 13, 13953 (2021).

Morgan, A. J. & Dobson, R. An analysis of water risk in the mining sector. Water Risk Filter Research Series 1, WWF. https://wwfint.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/analysis_of_water_risk_in_mining_sector__wwf_water_risk_filter_research_series_.pdf (2020).

Costache, R. et al. Flood susceptibility evaluation through deep learning optimizer ensembles and GIS techniques. J. Environ. Manag. 316, 115316 (2022).

Das, S. & Gupta, A. Multi-criteria decision based geospatial mapping of flood susceptibility and temporal hydro-geomorphic changes in the Subarnarekha basin. India. Geosci. Front. 12, 101206 (2021).

Seleem, O., Ayzel, G., De Souza, A. C. T., Bronstert, A. & Heistermann, M. Towards urban flood susceptibility mapping using data-driven models in Berlin, Germany. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk. 13, 1640–1662 (2022).

Ghosh, S. & Kundu, S. Flood risk assessment and numerical modelling of flood simulation in the Damodar River Basin, Eastern India. In Floods in the Ganga–Brahmaputra–Meghna Delta. (eds. Islam, A., et al.). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21086-0_13 (Springer Geography, 2023).

Hadipour, H. et al. Deep clustering of small molecules at large-scale via variational autoencoder embedding and K-means. BMC Bioinform. 23(Suppl 4), 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-022-04667-1 (2022).

Ginting, D. S. B., Efendi, S., Amalia, & Sihombing, P. Enhancing CURE algorithm with stochastic neighbor embedding (CURE-SNE) for improved clustering and outlier detection. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. (IJACSA). 15(12), 382 (2024).

Vardakas, G., Papakostas, I., & Likas, A. Deep clustering using the soft silhouette score: Towards compact and well-separated clusters. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.00608v1. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.00608v1 (2024).

Schroeder, A. J. et al. The development of a flash flood severity index. J. Hydrol. 541, 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.04.005 (2016).

National Weather Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, & NOAA’s National Weather Service. Floods: The Awesome Power. https://www.weather.gov/media/bis/Floods.pdf (2005).

The Wire. Floods Ravage West Bengal as State Battles Centre Over Damodar Water Release. https://thewire.in/environment/floods-ravage-west-bengal-as-state-battles-centre-over-damodar-water-release (2024).

NRSC, NDMA & Department of Disaster Management, West Bengal. Flood Hazard Atlas—West Bengal. National Remote Sensing Centre, Hyderabad. https://ndma.gov.in/sites/default/files/PDF/FHA/WB_FloodHazardAtlas.pdf (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank IIT (ISM) Dhanbad for providing the research milieu for conducting this work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S.R.: Conception and design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, review, and editing. He is the first author. V.G.K.V.: Conceptualization, analysed the data, reviewing, and editing. He is the corresponding author. S.K.: Analysed the data, reviewing, and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thappitla, R.S., Villuri, V.G.K. & Kumar, S. An autoencoder driven deep learning geospatial approach to flood vulnerability analysis in the upper and middle basin of river Damodar. Sci Rep 15, 33741 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96781-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96781-2