Abstract

Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases (BVMOs) are versatile biocatalysts that catalyse the oxidation of ketones to esters with high regio- and enantioselectivity, operating under mild reaction conditions while reducing hazardous waste. Some BVMOs can convert cellulose-derived alkyl levulinates to 3-acetoxypropionates (3-APs), which are key intermediates in the production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP), a versatile building block chemical. In this study, a BVMO from Acinetobacter radioresistens (Ar-BVMO) was tested as a biocatalyst for the conversion of three marketed alkyl levulinates: methyl, ethyl and butyl levulinate. The enzyme showed 4-fold higher catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) and enhanced regioselectivity for the desired 3-AP product (4:1 ratio) when using butyl levulinate as a substrate. Escherichia coli whole-cells over-expressing Ar-BVMO were exploited to increase the product yield, achieving 85% conversion in 9 h. To further improve the sustainability of this biotransformation, butyl levulinate was obtained via microwave-assisted alcoholysis of pulp, a renewable cellulose feedstock, achieving 92.7% selectivity. Despite challenges posed by poor solubility of the resulting mixture in aqueous environment, Ar-BVMO in cell lysates was able to fully convert butyl levulinate within 24 h, efficiently producing 3-HP precursors without additional purification steps. These findings highlight the feasibility of this chemoenzymatic approach to convert cellulose-based raw materials to platform chemicals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Baeyer-Villiger (BV) reaction is a versatile organic transformation that involves the oxidation of a variety of carbonyl compounds: linear ketones are converted into esters, cyclic ketones into lactones, benzaldehydes into phenols, and carboxylic acids and α-diketones into anhydrides. Traditionally, the reaction relies on the use of organic peracids, which provide a straightforward and effective synthetic pathway. However, these compounds are expensive and/or hazardous, and their use results in the formation of one equivalent of the corresponding carboxylic acid salt as waste, posing challenges to sustainability and environmental compatibility1,2. In this regard, biocatalysts have emerged as powerful tools for the synthesis of enantiopure fine chemicals, as they offer high selectivity, function under mild reaction conditions and generate minimal/no hazardous waste, thereby reducing environmental impact compared to conventional organic synthesis3,4.

Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases (BVMOs) are flavin-containing enzymes that can catalyse the insertion of an oxygen atom into their substrates using the free, abundant and green molecular oxygen (O2) as an oxidant and produce only water as a byproduct5. These enzymes exhibit broad substrate tolerance and high chemo-, regio-, and/or enantioselectivity, making them valuable tools for the synthesis of complex molecules used in the pharmaceutical, fragrance, and polymer industries6,7,8. For instance, a biocatalytic cascade involving a BVMO from Leptospira biflexa was designed for the synthesis of aroma compounds that are used as fragrance ingredients in cosmetic and non-cosmetic products, as well as flavours and aromas in food and drink preparations9. Additionally, a BVMO from Pseudomonas putida has been used in a multistep enzymatic reaction to obtain ω-hydroxy fatty acids (ω-HFAs), which are of great interest in the synthesis of polyamides, polyesters and other polymer materials10.

More interestingly, a few BVMOs have been found to catalyse the conversion of alkyl levulinates (e.g. methyl, ethyl and butyl levulinate) to 3-acetoxypropionates (3-APs), which are key intermediates in the production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP), recognized by the U.S. Department of Energy as one of the 12 top bio-based building-block chemicals11. 3-HP is a C3 non-chiral mono-carboxylic acid containing both -COOH and β-OH functional groups. It is used as a substrate to synthesize various industrially important chemicals, such as acrylic acid, acrylonitrile, 1,3-propanediol (1,3-PDO), acrylamide, propiolactone, etc12. Additionally, 3-HP acts as a coating, adhesive and antistatic agent, and is therefore used in the textile, adhesives, polymer, cosmetics, and paint industries13. With its broad range of applications, 3-HP has significant commercial potential, with an expected market value of more than USD 10 billion/year.14

Current research is mainly focused on the biotechnological production of 3-HP starting from renewable carbon sources, glycerol and glucose, through fermentation with metabolically engineered microbial strains15,16,17. However, a critical challenge for sugar-based 3-HP production at industrial scale is the limited yield, mainly caused by the preferential formation of by-products and the cytotoxic effects of 3-HP on microbial cells at high concentrations18. For this reason, alkyl levulinates can serve as an alternative carbon source for the biosynthesis of 3-HP. Alkyl levulinates are mainly produced from lignocellulosic biomass via levulinic acid esterification, which involves the preliminary acid-catalysed hydrothermal conversion of cellulose to levulinic acid, followed by its purification and hence esterification with the desired alkyl alcohol (e.g. methanol, ethanol, or butanol), adopting a suitable catalyst19. The one-pot synthesis of alkyl levulinates directly from monosaccharides, polysaccharides and lignocellulosic biomass has gained more interest due to the low cost of these feedstocks20.

Fink and Mihovilovic demonstrated that a variant of a BVMO from Comamonas could be exploited to produce ethyl 3-AP on the gram scale starting from ethyl levulinate using Escherichia coli whole-cells and their crude cell extracts21. Similarly, Liu and co-workers identified a BVMO from Rhodococcus pyridinivorans with high catalytic activity and excellent regioselectivity towards methyl levulinate, obtaining the corresponding methyl 3-AP with high yields22. However, less attention has been given to butyl levulinate, which is produced from levulinic acid using butanol. Butanol is biodegradable and safer than methanol and ethanol in terms of both toxicity and general handling. Moreover, there are no studies available on the feasibility of using enzymes for the BV oxidation of alkyl levulinates directly obtained from a renewable cellulose feedstock.

In this work, commercially available and pure alkyl levulinates were tested as possible substrates of a wild-type NADPH-dependent BVMO from Acinetobacter radioresistens (Ar-BVMO). Initially, reactions were carried out with the purified enzyme and characterised using different techniques: first a colorimetric assay, then a NADPH consumption assay, and finally gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Once demonstrated that butyl levulinate was the best substrate in terms of both total conversion and regioselectivity towards the desired product (i.e. butyl 3-AP), reactions were performed using Escherichia coli whole-cells over-expressing the enzyme to increase the yield. Moreover, butyl levulinate was obtained via microwave-assisted one-pot alcoholysis of pulp deriving from an industrial papermaking process to further improve the sustainability of the biocatalytic transformation. Finally, the mixture resulting from this reaction was directly subjected to enzymatic conversion using E. coli cell lysates containing Ar-BVMO to efficiently produce 3-HP precursors without any further purification steps.

Results and discussion

Ar-BVMO is an NADPH-dependent flavin-containing enzyme that can catalyse the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation on the carbonyl moiety of linear ketones, converting them to their corresponding esters23. Alkyl levulinates are linear esters which present an additional carbonyl group: it has been shown that a few other BVMOs can insert an oxygen atom next to this carbonyl group, leading to the formation of 3-acetoxypropionates (3-APs)21,22. For this reason, Ar-BVMO was heterologously expressed in E. coli and purified using affinity chromatography to test three commercially available alkyl levulinates – methyl, ethyl and butyl levulinate – as possible substrates. All reactions needed NADPH to reduce the enzyme’s flavin cofactor (FAD), which could subsequently activate molecular oxygen (O2) for later oxygen transfer to the substrate (Fig. 1A).

Colorimetric assay for substrate screening

In order to investigate the substrate selectivity of Ar-BVMO, a high-throughput colorimetric assay based on the formation of a purple-coloured complex was used24. Initially, all three alkyl levulinates were incubated with the purified Ar-BVMO at 30 °C for 2 h in presence of NADPH. Subsequently, reaction products were extracted, and the assay was performed as described in the Methods section. Solvent-extracted esters initially reacted with an alkaline hydroxylamine solution to produce hydroxamic acid, which was then combined with ferric iron to form a ferric hydroxamate complex with strong absorbance at 520 nm. The highest absorbance (i.e. the highest concentration of the ester product) was recorded for Ar-BVMO incubation with butyl levulinate. As shown in Fig. 1B, absorbance decreased from 0.34 ± 0.03 to 0.07 ± 0.01 when using ethyl levulinate instead of butyl levulinate whilst hardly any absorbance change at 520 nm was recorded for the reaction with methyl levulinate. These data suggest that only ethyl and butyl levulinate are substrates of Ar-BVMO: the enzyme, in presence of NADPH, converts these molecules to esters that can be detected spectrophotometrically following the assay. On the other hand, methyl levulinate was not accepted as a substrate. In general, a clear positive correlation between ester production and substrate chain length was observed (i.e. butyl > ethyl > methyl).

Substrate docking analysis

Substrate selectivity of Ar-BVMO was further investigated by performing an in silico molecular docking analysis with YASARA. Methyl, ethyl and butyl levulinates were docked into the active site of Ar-BVMO, whose 3D structure was predicted with AlphaFold 2Monomer v2.0 (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/D7PBN2). As shown in Fig. 1D and E, Trp289 facilitates the proper positioning of ethyl and butyl levulinates for the insertion of the oxygen atom next to their carbonyl group, which is in proximity to the cofactor (FAD) and the coenzyme (NADP+) involved in the reaction. In contrast, methyl levulinate interacts with FAD and NADP+ via its side chain, positioning the carbonyl group involved in the BV reaction away from the catalytic site (Fig. 1C). The key interactions (5.0 Å or less) with FAD, NADP+ and active site residues are listed in Fig. 1F.

The dissociation constant (KD) of butyl levulinate was found to be approximately 40 times lower than the one of methyl levulinate, and around 30 times lower than the one of ethyl levulinate (Supplementary Table S1).

These in silico results are in line with the in vitro results obtained with the colorimetric assay screening described in the previous paragraph, confirming the positive correlation between substrate chain length and substrate conversion.

In silico and in vitro analysis of Ar-BVMO reaction with three different alkyl levulinates: methyl (R = CH3), ethyl (R = CH2CH3) and butyl (R = CH2CH2CH2CH3) levulinate. A Reaction scheme. Ar-BVMO structure was predicted with AlphaFold2 Monomer v2.0 (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/D7PBN2). B Absorbance at 520 nm measured after performing a high-throughput colorimetric assay for detection of esters produced by Ar-BVMO reactions with alkyl levulinates. Data points are mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Binding and interactions (black dashed lines) within Ar-BVMO’s active-site were calculated using VINA software embedded in YASARA (https://www.yasara.org); C Methyl levulinate, D Ethyl levulinate and, E Butyl levulinate. The carbonyl group involved in the BV reaction is circled in dark green. F Distances (in Å) and interaction types of each substrate with Ar-BVMO’s active site residues, cofactor (FAD) and coenzyme (NADP+). Figures C, D and E were produced by the 3D molecular visualisation software PyMOL (https://www.pymol.org/).

Determination of kinetic parameters via NADPH consumption

A second spectrophotometric method based on NADPH consumption by Ar-BVMO in the presence of the 3 alkyl levulinates was investigated. In this assay the absorbance decrease at 340 nm was followed over time in presence of methyl, ethyl and butyl levulinate. Absorbance decreased more rapidly when butyl levulinate was added to the enzyme-NADPH mixture. The same behaviour was observed for ethyl levulinate but to a lesser degree. Instead, no difference in NADPH consumption could be detected after the addition of methyl levulinate. These data confirm the results obtained with the colorimetric assay: only ethyl and butyl levulinate are substrates of Ar-BVMO. At this point, kinetic parameters were measured by monitoring the NADPH consumption rates at 340 nm in a 200 s timeframe using increasing concentrations of both substrates. The obtained Michaelis-Menten curves are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. The calculated KM, kcat and kcat/KM are summarized in Table 1. The kcat for butyl levulinate was found to be 10 times higher compared to the one calculated for the other substrate. Although the enzyme showed higher affinity (i.e. lower KM) towards ethyl levulinate, the calculated catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) was found to be 4 times higher (Table 1) for the conversion of butyl levulinate, making this molecule a preferred substrate of Ar-BVMO.

Product identification and regioselectivity of Ar-BVMO

Since the NADPH consumption assay revealed ethyl and butyl levulinates as possible substrates of Ar-BVMO, the enzymatic products were identified via GC-MS. To this end, both substrates were incubated with the purified enzyme at 30 °C for 6 h. NADPH was added first to start the reaction, and then after 3 h to further enhance the catalysis. GC-MS analysis of the enzymatic reactions revealed that both substrates were converted into two regioisomeric products: 3-acetoxypropionates (3-APs, compounds 2 and 5 in Fig. 2) and methyl succinates (compounds 3 and 6 in Fig. 2). It is known that BVMOs can insert an oxygen atom next to the carbonyl group either on the most substituted side – producing “normal” acetoxypropionates – or on the less substituted side – generating “abnormal” succinates7,25. In this specific case, normal regioselectivity is particularly important since only 3-APs can be hydrolysed to 3-HP21,22. Moreover, a highly regioselective enzyme allows improved substrate utilization and reduced by-product formation, further simplifying the downstream separation and purification of the compound of interest. Ar-BVMO displayed higher normal regioselectivity for the conversion of butyl levulinate with butyl 3-AP as the main product of the enzymatic reaction, with a normal: abnormal ratio of 4:1 (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, ethyl levulinate was converted mainly to ethyl methyl succinate (normal: abnormal ratio of 1:2) (Fig. 2A). The mass spectra of ethyl and butyl 3-AP are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2 and Fig. S3. This data confirms that butyl levulinate is a better substrate than ethyl levulinate in terms of both total conversion (82% versus 48%) and regioselectivity towards the normal product.

GC-MS chromatograms with peak assignment for Ar-BVMO reactions with alkyl levulinates. A Reaction with ethyl levulinate (1) in presence (red) and in absence (blue, control) of NADPH. Two products are formed: ethyl 3-acetoxypropionate (2) and ethyl methyl succinate (3). B Reaction with butyl levulinate (4) in presence (red) and in absence (blue, control) of NADPH. Two products are formed: butyl 3-acetoxypropionate (5) and butyl methyl succinate (6).

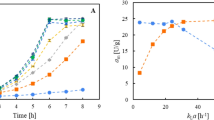

Butyl levulinate conversion by purified enzyme versus whole-cells

Once butyl levulinate was identified as the best substrate for Ar-BVMO, time-course reactions with purified enzyme and E. coli whole-cells were performed. The latter were carried out to determine the most efficient set-up for butyl 3-AP production. The purified Ar-BVMO could convert up to 40% of butyl levulinate in 2 h, generating mostly butyl 3-AP (38%) (Fig. 3A). The reaction was allowed to proceed for 8 h, but substrate conversion did not go beyond the aforementioned percentage. Addition of extra amounts of NADPH would most probably increase the catalytic activity of the enzyme, as already stated in the previous paragraph. However, NADPH is a metastable and expensive molecule that makes its continuous external addition economically unfeasible26. For this reason, exploiting a NADPH regeneration system in E. coli whole-cells overexpressing the enzyme would make butyl 3-AP production more cost-effective. Therefore, an NADPH regeneration system consisting of NADP+, citrate and MgCl2 was utilized. Citrate is hypothesized to be isomerized by aconitase to isocitrate which is subsequently decarboxylated by isocitrate dehydrogenase to 2-oxoglutarate and thereby producing NADPH by reduction of NADP+. This system utilizes intracellular enzymes of the host organism and has been previously shown to result in a sustained activity of different monooxygenases, Ar-BVMO included27,28,29,30.

In addition, previous research has also demonstrated that permeabilizing the cells is an effective way in order to increase the substrate conversion rate31,32,33. Therefore, different reagents including DMSO, TWEEN 20, TWEEN 80 and Triton X-100 were added to the reaction mixture in order to change the membrane permeability, thus allowing butyl levulinate to enter the cells. While TWEEN 20 and TWEEN 80 have no positive effect on substrate conversion, DMSO and Triton X-100 were found to improve the butyl levulinate conversion by 1.6 and 2.3 times, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S4). Given these results, 1% Triton X-100 was used as a permeabilization reagent for the subsequent time-course reactions, where substrate conversion was monitored via GC-MS every 3 h. As expected, the amount of butyl 3-AP produced over time increased with increasing concentrations of substrate (Supplementary Fig. S5). Whole-cells could almost fully convert up to 15 mM substrate – limit of solubility in aqueous environment, without any co-solvent addition – within 9 h (Fig. 3B). While substrate was being consumed, both regio-isomers accumulated over time. Butyl 3-AP was found to be the main product, with a relative amount of 85% in the 9 h reaction mixture (Fig. 3B). This set-up turned out to be highly efficient and faster than the previously reported whole-cell biotransformations, which were performed in LB medium for up to 24 h21. Supplementary Table S2 compares the efficiency of Ar-BVMO and other wild-type BVMOs in the oxidation of butyl levulinate in E. coli whole-cells. Moreover, there was no need to add any other enzymes to support the catalysis (e.g. glucose dehydrogenase for NADPH regeneration), making it easier and less expensive.

Time-course analysis of butyl levulinate conversion by Ar-BVMO. Data points are mean ± SD of three independent experiments. A Conversion of butyl levulinate by purified Ar-BVMO. The reactions were stopped at different times (0 min, 10 min, 30 min, 2 h, 4 h and 8 h). Butyl levulinate (blue circles) was mainly converted to butyl 3-AP (red squares). Butyl methyl succinate (green triangles) was also detected. Reaction conditions: 2 µM Ar-BVMO, 7 mM substrate, 7 mM NADPH, 30 °C, 200 rpm. B Conversion of butyl levulinate by E. coli whole-cells over-expressing Ar-BVMO. The reactions were stopped at different times (0 h, 3 h, 6 h, and 9 h). Reaction conditions: 3 mL E. coli BL21 (DE3) (OD600 = 10), 1% Triton X-100, 15 mM substrate, NADPH regeneration system, 30 °C, 180 rpm.

Proposed route towards 3-hydroxypropionic acid

To make this enzymatic reaction even more sustainable, the possibility to obtain 3-HP precursors starting from a renewable cellulose feedstock was investigated. To this end, we designed a chemo-enzymatic route considering that: (i) the starting material should come from renewable resources; (ii) the route must pass through the biocatalyst’s preferred substrate (i.e. butyl levulinate); (iii) the use of too many purifications steps should be avoided; and (iv) the reagents needed for the process should be cheap and easily accessible. The proposed route consisted of three steps (Fig. 4): first, production of butyl levulinate via butanolysis of cellulose from hardwood pulp (Fig. 4, reaction a); second, enzymatic conversion of the produced butyl levulinate into butyl 3-AP by Ar-BVMO (Fig. 4, reaction b); and third, hydrolysis of butyl 3-AP to 3-HP (Fig. 4, reaction c). With this strategy, all the conditions set at the beginning are met, since (i) hardwood pulp derives from lignocellulosic biomass, which is abundant, renewable and can be sourced from various agricultural and forestry residues; (ii) the selected treatment leads to the production of butyl levulinate, which is the preferred alkyl levulinate substrate of the biocatalyst of choice; (iii) the mixture obtained from pulp alcoholysis is mainly composed of butyl levulinate, which does not need to be necessarily separated from other reaction intermediates or by-products to be recognized and converted by the enzyme; and (iv) all the solvents, acids and salts needed for each step are of common use and readily available. Here we focused our attention on the first two steps of the proposed route, performing a microwave-assisted one-pot butanolysis of hardwood pulp followed by Baeyer-Villiger enzymatic conversion of the obtained reaction mixture.

It has been previously reported that 3-APs can easily form 3-hydroxypropionates in aqueous environment at sub-physiological pH19. This includes butyl 3-AP, whose acetate moiety can be cleaved to obtain butyl 3-hydroxypropionate (i.e. 3-HP butyl ester), which can be further hydrolysed to 3-HP (Fig. 4, dotted lines).

The proposed route for the synthesis of 3-hydropropionic acid (3-HP) starting from hardwood pulp. The cellulose fibers forming the pulp are converted to butyl levulinate through microwave-assisted one-pot alcoholysis (reaction a). Butyl levulinate is the substrate of Ar-BVMO, which catalyses the insertion of an oxygen atom next to the carbonyl group in presence of O2 and NADPH (reaction b). The resulting butyl 3-acetoxypropionate (butyl 3-AP) can be further hydrolysed to 3-HP (reaction c). Cleavage of the acetate moiety of butyl 3-AP leads to the formation of butyl 3-hydroxypropionate (3-HP butyl ester), which can also be hydrolysed to give 3-HP.

Microwave-assisted Butyl levulinate production from cellulose and hardwood pulp

The alcoholysis reaction in butanol to produce butyl levulinate was carried out in a microwave reactor. Microwave heating represents an important tool to improve the efficiency of this process, since it can reduce reaction time and energy consumption34,35. Preliminary studies were performed on commercial cellulose to determine the best reaction conditions (i.e. acid catalyst, temperature, incubation time), which were chosen based on the previous literature36,37,38. The results are shown in Table 2. In presence of a low content of H2SO4 (1.2% w/w), almost all cellulose (95.4%) was converted after 30 min. However, GC-FID analysis of the crude mixture revealed that the selectivity towards butyl levulinate was low (58.8%). Increasing the reaction time to 1 h boosted this value up to 100%. p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TsA, 0.25 M) was also tested as the acid catalyst at 225 °C, with the addition of KBr or KCl as co-catalysts. KCl proved to be more effective than KBr since high cellulose conversion (90.6%) was achieved after only 2 min. However, selectivity was found to be low (26.7%). Taken together, the best conditions were found to be 1.2% w/w H2SO4, 190 °C temperature, 1 h total reaction time. These conditions were subsequently applied to hardwood pulp deriving from an industrial papermaking process, hence a renewable cellulose feedstock (Table 3). The process resulted in a 93.2% conversion of the starting material and 60% selectivity towards the desired compound. To improve this result, the reaction temperature was raised to 225 °C. 1H-NMR analysis of this sample revealed both high conversion (87.6%) and high selectivity (92.7%), even though hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF- a reaction intermediate) and dibutyl ether (DBE - a by-product from butanol condensation), were also detected (Supplementary Fig. S6). The molar yield of butyl levulinate was 36.9%, which was satisfactory considering the low amount of acid catalysts used for the reaction. Moreover, butyl levulinate represents 72.2% w/w of the final reaction mixture, thus making it a valuable starting point – in terms of purity grade – for the following enzymatic step.

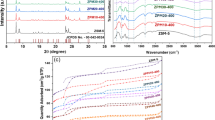

Enzymatic conversion of Butyl levulinate obtained from hardwood pulp

As already mentioned, the mixture obtained from butanolysis of hardwood pulp – after filtration of the unreacted starting material – consisted of butyl levulinate (ca. 72% w/w), DBE (ca. 28% w/w) and HMF (in traces). This mixture was not subjected to any further purification step prior to enzymatic conversion to make the whole process faster and more practical for large-scale applications. Initially, the reaction was performed with purified Ar-BVMO in buffer: after 6 h, the enzyme could only convert 16% of butyl levulinate into butyl 3-AP. The low turnover could be due to the poor solubility of the mixture in aqueous solution, which makes the enzyme-substrate encounter more challenging. The same set of experiments were subsequently carried out using E. coli whole-cells over-expressing Ar-BVMO. The product yield worsened, with hardly any detectable product peak in GC-MS. A possible explanation could lie in the presence of DBE in the mixture, which is likely to be toxic for the recombinant host organism. In order to circumvent this problem, we opted for E. coli cell lysate reactions. As shown in Fig. 5, the production of butyl 3-AP (desired normal product) increased up to 42% in 6 h. As mentioned earlier, butyl 3-AP can spontaneously hydrolyse to 3-HP butyl ester, thus decreasing the presence of normal enzymatic product in the reaction mixture. Therefore, an additional 16% – relative to 3-HP butyl ester – must be taken into consideration, increasing the yield up to 58%. After 24 h, almost all butyl 3-AP was consumed, and 86% of the reaction mixture consisted of 3-HP butyl ester. These results highlight the potential of the proposed route to convert cellulose-based raw material to 3-HP precursors in a selective and “green” manner compared to traditional chemical methods.

Time-course analysis of cell lysate biotransformation of butyl levulinate from hardwood pulp. The reactions were stopped at different times (0 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h). Initially, butyl levulinate (blue circles) was converted to butyl 3-AP (red squares) and butyl methyl succinate (green triangles). After 6 h, a new product (3-HP butyl ester, purple triangles) forms as a result of butyl 3-AP spontaneous hydrolysis. Reaction conditions: 1 mL reaction volume, 5 mM substrate, NADPH regeneration system, 30 °C, 180 rpm. Data points are mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Conclusion

In this study, a wild-type NADPH-dependent Bayer-Villiger monooxygenase from Acinetobacter radioresistens (Ar-BVMO) was investigated as a potential biocatalyst for the conversion of cellulose-derived alkyl levulinates to 3-acetoxypropionates (3-APs), which are key intermediates in the synthesis of 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP), a versatile platform chemical.

Initially, the catalytic activity and regioselectivity of the purified enzyme were assessed using three commercially available and pure alkyl levulinates: methyl, ethyl, and butyl levulinate. A NADPH consumption assay revealed that Ar-BVMO can convert butyl levulinate 10 times faster than ethyl levulinate (kcat = 27.30 ± 0.77 min− 1). Moreover, GC-MS analysis indicated an enhanced regioselectivity for the 3-AP product (i.e. normal ester) when using butyl levulinate as a substrate.

Considering these findings, butyl levulinate was selected to carry out whole-cell reactions to improve the product yield. Escherichia coli whole-cells over-expressing Ar-BVMO and supplemented with a citrate-based NADPH regeneration system proved to be an efficient set-up, achieving 85% conversion of butyl levulinate into butyl 3-AP within only 9 h. These results are of particular interest, considering that: (i) the enzyme was used in its wild-type form, presenting opportunities to enhance selectivity and/or broaden substrate specificity through active site mutagenesis; and (ii) previous research mainly focused on the bioconversion of methyl and ethyl levulinate, making the investigation of butyl levulinate especially compelling.

To further improve the sustainability of the biocatalytic transformation, the enzyme’s preferred substrate was obtained via one-pot alcoholysis of pulp, a renewable cellulose feedstock using a microwave-assisted process. The best results were obtained in presence of a low content of H2SO4 (1.2% w/w) at 225 °C in 1 h, with a total conversion of 87.6% and 92.7% selectivity towards the desired compound. The mixture was directly subjected to enzymatic conversion, thereby eliminating the need for additional purification steps. Despite challenges posed by poor solubility of this mixture in aqueous buffer solution, the employment of Ar-BVMO in Escherichia coli cell lysates allowed 89% conversion of butyl levulinate in only 6 h. Notably, spontaneous hydrolysis of the main enzymatic product (i.e. butyl 3-AP) resulted in significant formation of 3-HP butyl ester, with 86% of the 24-hour reaction mixture comprising this 3-HP precursor.

These preliminary findings underscore the potential of this chemo-enzymatic approach, demonstrating efficient conversion of pulp into 3-HP precursors by integrated microwave-assisted alcoholysis and Ar-BVMO biotransformation. Finally, the proposed route offers a “green” alternative to produce 3-HP from a renewable cellulose feedstock, paving the way for novel sustainable pathways towards this high-added value building-block chemical.

Methods

Materials

Monopotassium phosphate, glycerol, ampicillin, isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), octylphenoxy poly(ethyleneoxy)ethanol (IGEPAL), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) disodium salt, iron(III) chloride, sodium hydroxide, β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reduced form (NADPH), β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+), trisodium citrate, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), TWEEN 20, TWEEN 80, Triton X-100, methyl levulinate, ethyl levulinate, butyl levulinate, n-butanol, hexane, methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), sulphuric acid, p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TsA), perchloric acid and cellulose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Dipotassium phosphate, riboflavin, hydroxylamine hydrochloride and magnesium chloride were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Ethanol absolute was purchased from VWR. High alpha cellulose hardwood pulp (Södra purple) was purchased from Södra (Växjö, Sweden).

Enzyme expression and purification

Ar-BVMO was expressed in E. coli and purified via affinity chromatography according to the previously published methodology23,39. Briefly, 10 mL of overnight liquid culture of E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells transformed with pT7-BVMO were used to inoculate 1 L LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg mL− 1) and riboflavin (20 µg mL−1). The cells were grown at 37 °C and 200 rpm until OD600 of 0.6 was reached. Protein expression was induced by the addition of IPTG, and the temperature was lowered to 24 °C. The cells were harvested 20 h post-induction by centrifugation at 4000 rpm at 4 °C and the pellet was stored at -20 °C until further use. Protein purification was performed on a 5 mL HisTrap Fast Flow column. The bound enzyme was eluted by addition of 300 mM imidazole and the fractions displaying the characteristic flavin spectrum with absorbance maxima at around 375 and 450 nm were pooled and buffer exchanged with Amicon centrifugal units (30 kDa cut off). The final yield was 4 mg L−1.

Colorimetric assay for alkyl levulinates conversion screening

The procedure described by Löbs et al. for the high-throughput quantitative analysis of ester biosynthesis was followed to screen different alkyl levulinates as possible substrates of Ar-BVMO20. First, enzyme-substrate incubations were performed at 30 °C using 5 mM NADPH and 7 mM of methyl, ethyl, or butyl levulinate in 200 µL of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The reactions were started by adding 3 µM of the pure protein and, after 2 h, were terminated by adding 200 µL of hexane. Control reactions were carried out in absence of NADPH. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min and the extraction continued for 10 min at room temperature with orbital shaking at 200 rpm. After settling, 60 µL of the hexane layer was transferred into a flat bottom 96-well plate. Hydroxymates were produced by combining 20 µL of hydroxylamine stock solution (2.5% w/v of hydroxylamine in 95% ethanol mixed with 2.5% w/v of sodium hydroxide in 95% ethanol at a 1:1 ratio) with 60 µL of hexane extracted esters and allowing the reaction to proceed for 10 min. Subsequently, 120 µL of the ferric working solution (0.4% w/v iron(III) chloride in 50% perchloric acid and 50% Milli-Q water, diluted 1:20 in ethanol) was added and incubated for 5 min. The production of ferric hydroxamate was measured at 520 nm using SPECTROstar Nano absorbance microplate reader (BMG LABTECH).

In silico molecular docking simulations

In the absence of a crystal structure, in silico molecular docking experiments were carried out using the AlphaFold 2 model of Ar-BVMO. Cofactors, specifically FAD and NADP+, were added to the model using a crystallographic structure as a reference (BVMOAFL210 from Aspergillus flavus in complex with NADP+, PDB ID: 6Y48). The ligands – methyl, ethyl and butyl levulinate – were obtained from the Chemspider database40. 999 runs of docking were run centring a simulation cell of 5 × 5 × 5 Å around the FAD cofactor using the VINA software embedded in YASARA (https://www.yasara.org). Asp 56, Ser 57, Tyr 141, Tyr 142 residues were kept flexible. The energy minimization was performed using the default settings of the software.

Calculation of steady state parameters by NADPH consumption assays

The steady state kinetic parameters for ethyl levulinate and butyl levulinate were determined spectrophotometrically by monitoring the NADPH consumption rates (A.U./s) at 340 nm using 0–5 mM ethyl levulinate and 0–15 mM butyl levulinate. The samples were evaluated in a total volume of 0.35 mL containing 1 µM enzyme and 160 µM of NADPH. Reactions were followed for 200 s at 30 °C in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4.

Enzymatic product(s) detection and identification by GC-MS

To characterize the enzymatic products, reactions were conducted at 30 °C in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, with 4 µM Ar-BVMO, 4 mM NADPH and 7 mM substrate (ethyl or butyl levulinate). A neutral pH was selected based on previously reported reaction conditions for the conversion of linear ketones and alkyl levulinates21,23. Although the optimum temperature for Ar-BVMO is 37 °C, the reaction temperature was lowered to 30 °C to extend the half-life of this biocatalyst and maintain its activity for a longer period of time28. The substrate concentration was set above the calculated KM value while remaining within solubility limits.

After 3 h, more NADPH was added to further carry on the reaction. After 6 h, MTBE was added to the mixture to stop the reactions (1:1 volumetric ratio). The produced esters were extracted by vortexing for 2 min, and then centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The organic phase was separated and dried with MgSO4. Samples were diluted 1:10 in MTBE before analysis. GC-MS measurements were performed using a Shimadzu single quadrupole GCMS-QP2020 NX equipped with a SH-I-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). Helium was used as a carrier gas with a flow of 1.85 mL min−1 and the injector temperature was set to 250 °C. Oven temperature was kept at 70 °C for 2 min, then it was raised at 15 °C min−1 up to 300 °C and held for 5 min. Mass spectra were collected using electrospray ionization.

Whole-cell biotransformation of Butyl levulinate

For Ar-BVMO-mediated whole-cell catalysis, E. coli BL21 (DE3) cell pellets transformed with the expression vector pT7-BVMO were resuspended in 3 mL of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, to a final OD600 of 10. Reactions were carried out for 9 h at 30 °C with 180 rpm shaking. As NADPH cofactor regeneration system, NADP+ (0.3 mM), trisodium citrate (50 mM) and MgCl2 (10 mM) were used to sustain the catalysis. Butyl levulinate was added at different concentrations: 5 mM, 10 mM, 15 mM. DMSO (0.4%), TWEEN 20 (1%), TWEEN 80 (1%) and Triton X-100 (1%) were used as permeabilization reagents to allow the substrate to enter cells freely33. Samples of 500 µL were collected after 0, 3, 6 and 9 h and mixed with 1 mL of MTBE. The reaction products were extracted as described above. GC-MS analyses were performed in an Agilent Technologies 7890B Network GC System with a 5977B Network Mass Selective Detector using a DB-VAX capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.5 μm). Helium was used as a carrier gas with a flow of 1 mL min−1 and the injector temperature was set to 250 °C. Oven temperature was kept at 70 °C for 5 min, then it was raised at 5 °C min−1 up to 100 °C and held for 5 min, and finally raised at 10 °C min−1 up to 170 °C and held for 5 min. Mass spectra were collected using electrospray ionization.

Microwave-assisted alcoholysis of cellulose and hardwood pulp into Butyl levulinate

The alcoholysis of cellulose and hardwood pulp into butyl levulinate was performed in a multimodale microwave reactor (SynthWAVE by Milestone srl, Sorisole, Italy) equipped with multiple gas inlets. The starting material (1 g) was mixed with n-butanol (12 mL) and H2SO4 (1.2% w/w) or a solution of p-TsA (0.25 M) were added as acid catalysts. When using p-TsA, KCl or KBr were also used as co-catalysts. Reactions were run in 15 mL glass vials immersed in 200 mL of brine solution. Mass transfer was provided through magnetic stirring. The mixtures were irradiated at 1500 W under inert atmosphere (N2, 40 bar). Heating ramps of 3 min and 6 min were used for reactions performed at 190 °C and 225 °C, respectively. After the reaction, the crude was recovered and filtered over paper to separate the unreacted starting material. The filter was vacuum dried and weighted to calculate the % of conversion of the substrate. The filtrate was dried under vacuum, redissolved in ethyl acetate, and analysed by GC-FID using an Agilent Technologies 7820 A Network GC System equipped with a FID detector and a HP-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). Helium was used as a carrier gas with a flow of 1.2 mL min−1 and the injector temperature was set to 250 °C. Oven temperature was kept at 50 °C for 5 min, then it was raised at 10 °C min−1 up to 100 °C, then at 20 °C min−1 up to 230 °C and finally at 20 °C min−1 up to 300 °C, with 1 min equilibration time. Butyl levulinate quantification was performed by external calibration curves based on peak areas of the pure standard. Selectivity was derived from the relative percentage area of the desired product peak after the integration of all the detected peaks. The molar yield was calculated as (moles of product/moles of glucose in starting material) × 100. Crude extracts were also dried and dissolved (10 mg) in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3, 0.7 mL) to be analysed by 1H NMR using a Jeol JNM-ECZ600R spectrometer (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) operating at a frequency of 600 MHz.

Cell lysate reactions with Butyl levulinate produced from alcoholysis of hardwood pulp

The cell pellet obtained after Ar-BVMO over-expression was resuspended in 20 mL of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.2 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM FAD, 0.2 mM NADP+ and 1% IGEPAL. Cells were lysed by sonication (15% amplitude, 30 s pulse, 60 s pause, 6 cycles) and subsequentially stirred at 4 °C for 10 min. The lysate was kept on ice until use. Butyl levulinate produced from the microwave-assisted alcoholysis of hardwood pulp was used as a substrate. The filtrate dissolved in ethyl acetate was dried under vacuum and the obtained black oil was redissolved in ethanol resulting in a 5 M stock solution. The use of a sonicator bath was necessary to then dissolve the oil in a solution containing 0.6 mM NADP+, 20 mM MgCl2, 100 mM trisodium citrate in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The final butyl levulinate concentration in this solution was 10 mM. The solution was mixed with the cell lysate in a 1:1 volumetric ratio to start the reaction. Samples of 300 µL were collected after 0, 3, 6 and 24 h and the reaction was terminated by adding 600 µL of MTBE. The reaction products were extracted and analysed by GC-MS as previously described.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Brink, G. J., Arends, I. W. C. E. & Sheldon, R. A. The Baeyer – Villiger reaction: new developments toward greener procedures. Chem. Rev. 104 https://doi.org/10.1021/cr030011l (2004).

Fatima, S. et al. Baeyer–Villiger oxidation: a promising tool for the synthesis of natural products: a review. RSC Adv. 14 https://doi.org/10.1039/D4RA03914A (2024).

Aslan, A. S. et al. Semi-Rational design of Geobacillus stearothermophilus L-Lactate dehydrogenase to access various chiral α-Hydroxy acids. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 179 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-016-2007-x (2016).

Rowles, I. et al. Engineering of phenylalanine ammonia lyase from Rhodotorula Graminis for the enhanced synthesis of unnatural l-amino acids. Tetrahedron 72 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2016.06.026 (2016).

Fürst, M. J. L. J., Gran-Scheuch, A., Aalbers, F. S. & Fraaije, M. W. Baeyer–Villiger monooxygenases: tunable oxidative biocatalysts. ACS Catal. 9 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.9b03396 (2019).

Liu, F. et al. A Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase from Cupriavidus basilensis catalyzes asymmetric synthesis of (R)-lansoprazole and other pharmaco-sulfoxides. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 105 (8), 105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-021-11230-0 (2021). 2021-03-29.

Schwendenwein, D. et al. Chemo-Enzymatic cascade for the generation of fragrance aldehydes. Catalysts 2021. 11, 07–30. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11080932 (2021).

Bučko, M. et al. Baeyer-Villiger oxidations: biotechnological approach. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 100 (2016). (2016-06-21). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-016-7670-x.

Ceccoli, R. D. et al. Sequential chemo–biocatalytic synthesis of aroma compounds. Green Chem. 25, https://doi.org/10.1039/D2GC02866B (2023).

Zhang, G. X. et al. Discovery and Engineering of a Novel Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenase with High Normal Regioselectivity. ChemBioChem 22 (2021). /04/06 https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.202000478

Werpy, T. & Petersen, G. Top Value Added Chemicals from Biomass: I -- Results of Screening for Potential Candidates from Sugars and Synthesis Gas. (2004). https://doi.org/10.2172/15008859

Della Pina, C., Falletta, E. & Rossi, M. A green approach to chemical Building blocks. The case of 3-hydroxypropanoic acid. Green Chem. 13 https://doi.org/10.1039/C1GC15052A (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Notable improvement of 3-Hydroxypropionic acid and 1,3-Propanediol coproduction using modular coculture engineering and pathway rebalancing. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9 https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c00229 (2021).

Bhagwat, S. S. et al. Sustainable production of acrylic acid via 3-Hydroxypropionic acid from lignocellulosic biomass. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9 https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c05441 (2021).

Kildegaard, K. R., Wang, Z., Chen, Y., Nielsen, J. & Borodina, I. Production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from glucose and xylose by metabolically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metabolic Eng. Commun. 2 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meteno.2015.10.001 (2015).

Oliveira, D. M., Mota, T. R., Ferrarese-Filho, O. & Santos, W. D. d. Sustainable production of succinic acid and 3-hydroxypropionic acid from renewable feedstocks. Production of Top 12 Biochemicals Selected by USDOE from Renewable Resources (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823531-7.00008-1

Rathnasingh, C. et al. Production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid via malonyl-CoA pathway using Recombinant Escherichia coli strains. J. Biotechnol. 157 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.06.008 (2012).

Liang, B. et al. Recent advances, challenges and metabolic engineering strategies in the biosynthesis of 3-hydroxypropionic acid. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 119 https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.28170 (2022). /10/01).

Di Bucchianico, M. Production of levulinic acid and alkyl levulinates: a process insight. Green Chem. 24 https://doi.org/10.1039/D1GC02457D (2022).

Wang, M., Peng, L., Gao, X., He, L. & Zhang, J. Efficient one-pot synthesis of alkyl levulinate from xylose with an integrated dehydration/transfer-hydrogenation/alcoholysis process. Sustainable Energy Fuels. 4 https://doi.org/10.1039/C9SE00982E (2020).

Fink, M. J. & Mihovilovic, M. D. Non-hazardous Baeyer–Villiger oxidation of levulinic acid derivatives: alternative renewable access to 3-hydroxypropionates. Chem. Commun. 51 https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CC08734H (2015).

Liu, Y. Y., Li, C. X., Xu, J. H. & Zheng, G. W. Efficient synthesis of Methyl 3-Acetoxypropionate by a newly identified Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85 https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00239-19 (2019).

Catucci, G. et al. Characterization of a new Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase and conversion to a solely N-or S-oxidizing enzyme by a single R292 mutation. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Proteins Proteom. 1864 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.06.010 (2016).

Löbs, A. K., Lin, J. L., Cook, M. & Wheeldon, I. High throughput, colorimetric screening of microbial ester biosynthesis reveals high Ethyl acetate production from Kluyveromyces Marxianus on C5, C6, and C12 carbon sources. Biotechnol. J. 11 https://doi.org/10.1002/biot.201600060 (2016).

Leisch, H., Morley, K. & Lau, P. C. K. Baeyer – Villiger monooxygenases: more than just green chemistry. Chem. Rev. 111 (May 4). https://doi.org/10.1021/cr1003437 (2011).

Wu, H. et al. Methods for the regeneration of nicotinamide coenzymes. Green Chem. 15 https://doi.org/10.1039/C3GC37129H (2013).

Oeggl, R. et al. Frontiers | citrate as Cost-Efficient NADPH regenerating agent. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 6 https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2018.00196 (2018).

Catucci, G. et al. Green production of Indigo and indirubin by an engineered Baeyer–Villiger monooxygenase. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 44 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2022.102458 (2022).

Catucci, G. et al. Production of drug metabolites by human FMO3 in Escherichia coli. Microbial Cell Factories 2020 19:1 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-020-01332-1

Hanlon, S. P. et al. Expression of Recombinant human flavin monooxygenase and moclobemide-N-oxide synthesis on multi-mg scale. Chem. Commun. 48 https://doi.org/10.1039/C2CC17878H (2012).

Li, J. Y. et al. Effect of Tween Series on Growth and cis-9, trans-11 Conjugated Linoleic Acid Production of Lactobacillus acidophilus F0221 in the Presence of Bile Salts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2011, Vol. 12, Pages 9138–9154 12 (2011). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms12129138

Wang, G. L. et al. Triton X-100 improves co-production of β-1,3-D-glucan and pullulan by Aureobasidium pullulans. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2020 104:24 104 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10992-3

Wang, L. et al. Efficient biosynthesis of 10-Hydroxy-2-decenoic acid using a NAD(P)H regeneration P450 system and Whole-Cell catalytic biosynthesis. ACS Omega. 7 https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c00972 (2022).

Huang, Y. B., Yang, T., Cai, B., Chang, X. & Pan, H. Highly efficient metal salt catalyst for the esterification of biomass derived levulinic acid under microwave irradiation. RSC Adv. 6 https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA24305J (2015).

Szabó, Y. et al. Microwave-induced base-catalyzed synthesis of Methyl levulinate, a further improvement in dimethyl carbonate-mediated valorization of levulinic acid. Appl. Catal. A. 651 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2022.119020 (2023).

Antonetti, C. et al. Production of levulinic acid and n-Butyl levulinate from the waste biomasses grape pomace and Cynara cardunculus L. Proc. 1st Int. Electron. Conf. Catal. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECCS2020-07549 (2020).

Lorente, A. et al. Microwave radiation-assisted synthesis of levulinic acid from microcrystalline cellulose: application to a melon rind residue. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 237 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124149 (2023).

Raspolli Galletti, A. M. et al. Insights on Butyl levulinate bio-blendstock: from model sugars to paper mill waste cellulose as feedstocks for a sustainable catalytic butanolysis process. Catal. Today. 418 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2023.114054 (2023).

Minerdi, D., Zgrablic, I., Sadeghi, S. J. & Gilardi, G. Identification of a novel Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase from acinetobacter radioresistens: close relationship to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis prodrug activator EtaA. Microb. Biotechnol. 5 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7915.2012.00356.x (2012).

Pence, H. E., Williams, A. & ChemSpider An online chemical information resource. J. Chem. Educ. 87 https://doi.org/10.1021/ed100697w (2010).

Acknowledgements

Melissa De Angelis is the recipient of a three-year PhD scholarship (PON D.M.1061), University of Torino.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SJS; data curation: MDA; investigation: MDA, FB, GCA; methodology: MDA, FB, DC, CR; resources: GG and SJS; supervision: SJS; visualization: MDA; writing (original draft): MDA and SJS; writing (review & editing): MDA, FB, ST, GCR, GG and SJS. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

De Angelis, M., Correddu, D., Bucciol, F. et al. Biocatalytic production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid precursors using a regioselective Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase. Sci Rep 15, 13986 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96783-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96783-0