Abstract

Bird population estimation over broad spatial and temporal scales is a key objective in ornithology. To date, bird ecologists mainly relied on standard point counts where the number of detected individuals is interpreted as either the true abundance or proportionally related to it. However, providing accurate estimates of species abundance requires modelling the observation process with temporally replicated data, which is not always possible with the increasing use of ever-bigger datasets from citizen science programs. Data integration methods allow combining temporally replicated sampling at coarser spatial grains with data collected over larger spatial extents. Here, we developed an Integrated distance sampling (IDS) to combine national structured and semi-structured citizen-based bird surveys in France to estimate species abundances using observation distances and accounting for availability, i.e. the probability of individuals being detectable during a given sampling visit. While our simulation study showed an overall increase in the accuracy of estimated parameters for both ecological and observation processes, without significant biases, our case study suggests that such model improvements will depend on specific sampling scenarios. Integrated models represent a promising tool for ecological science, permitting the joint use of large unstructured datasets with scale-restricted structured surveys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To estimate bird species abundance, ornithologists mainly rely upon standardised point-count methods consisting of individual records of detected birds, either visual or auditory, over a given time period1. While standard models like GLMs (generalised linear models) allow extrapolating these observed counts to novel unsampled conditions through covariates, they also imply that the number of detected individuals represent an accurate estimate of true abundance, or corresponds to a constant proportion of the sampled population across space and time2,3. However, multiple studies have shown that this assumption is not always viable2,4,5 because of variations in species detectability arising from observation errors3, or changes in species phenologies6. can affect the actual proportion of detected individuals.

For a set sampling effort, data collection faces a trade-off between (i) the sampling of a large quantity of unstructured data across a broad spatial scale, or (ii) sampling of highly standardised data collected at a smaller scale7. Given the nature and volume of data collected by standard protocols, ecologists must address this issue relying increasingly on more or less opportunistic or semi-structured Citizen Science (CS) programs8. However, reliable abundance estimates require additional information such as repeated visits, collection of detection distances or data collected by multiple observers, to enable the combined modelling of the distinct ecological and observation processes9, see Box 1.

While the ecological process corresponds to species response to environmental covariates variations through space and/or time, the observation process depicts a probabilistic representation of mechanism underlying data collection10. Nichols et al.,11 describe the observation process as being represented by four components; (i) the probability that individuals’ home ranges overlap the sampling units \({p}_{s}\); (ii) given \({p}_{s}\), the probability that individuals are present on the sampling units during observers visits \({p}_{p}\); (iii) the probability that individuals’ are available for detection (for instance, bird vocalizing during observer visits) denoted \({p}_{a}\) and (iv) the probability of detection given individuals presence and detectability \({p}_{d}\). While \({p}_{s}\) is assessed through sampling design and \({p}_{d}\) can be inferred from specific data collection, such as detection distances; \({p}_{a}\) and \({p}_{p}\) probabilities require temporal replicates to be estimated12.

Ecological inferences, explicitly accounting for the ecological and observation processes, require flexible statistical tools such as hierarchical models able to account for global model complexity by a succession of submodels of lesser complexity13. These models vary depending on the studied ecological process14 from species presence/absence – (occupancy models; Ref.15) to species abundance – (hierarchical distance sampling,16; N-mixture models,17) or demographic parameters estimation – (Cormack-Jolly-Seber models, Ref.18).

In the last two decades, Citizen Science has seen exponential growth19 thanks to the development of several online databases such as eBird (www.ebird.org), iNaturalist (www.inaturalist.org) and GBIF (www.gbif.org) aiming to handle observation data collected by volunteers20 over increasingly longer temporal and larger spatial scales21. These databases rely mostly on opportunistic data, information gathered without sampling design or focused taxa21. While the use of metadata and ad hoc filters can increase the value of collected data22, Citizen Science tends to lack specificities of structured surveys, including intra- and inter-year repeated visits23,24.

Data integration, or the simultaneous joint analysis of an ecological process using multiple datasets25 developed a growing interest in recent years26,27. It is used, for instance, in the case of complex ecological inference requiring different data sources, such as integrated population models (IPM;25). These models rely on count data as well as nest monitoring and/or banding to infer population spatiotemporal variations and population growth parameters28,29; or to combine data collected at different spatial and/or temporal resolutions30.

Here, we focus on data collected for breeding bird atlases, depicting known distribution and population size estimates using data collected over a short timeframe. In France, the previous breeding bird atlas31 was based on a semi-quantitative method to estimate national population size32. This approach extrapolated bird densities locally determined over a few local areas without accounting for the detection process. It resulted in biased estimations of French breeding bird populations when compared to estimates inferred from a structured CS scheme EPOC-ODF (Structured Estimation of Common Bird Population Size, see33). While structured schemes result in intensive data collection to collect high-quality data, they tend to be conducted over a rather limited spatial extent. In contrast, semi-structured schemes aim at overcoming this issue to gather interpretable data while still enlisting the largest possible number of observers and associated field data34. For our study, we used datasets from both the structured CS scheme EPOC-ODF and the semi-structured CS scheme EPOC (Estimation of Common Bird Population Size), where one scheme allows inference of the detection process through repeated visits, while the other focuses on the collection of environmental data without repeated visits, akin to a double-sampling design35.

Recent studies have shown the potential of data integration on ecological inferences combining data from multiple data sources for occupancy modelling36,37 and species abundance estimates38. In this study, we relied on a joint likelihood approach39 based on the integrated distance sampling (IDS) formulation from38. While Kéry et al.,38 formulated an IDS model integrating data from unreplicated distance sampling data using point count and detection/non-detection data assessing species availability through list duration, we aim to calibrate an IDS model accounting for species availability through temporal replicates. Availability, or temporary emigration11,12,17, can represent different biological processes, such as (i) random temporary emigration, when individuals display conspicuous behaviours allowing increased detection rate during survey (birds vocalisations40, burrowing or diving41,42); (ii) spatial temporary emigration, where individuals remain undetected due to being physically outside the sampled sites during survey period; and (iii) availability resulting from variation in population-level processes, such as recruitment, survival, emigration or immigration13,43. Survey duration, addressed in38, accounts primarily for random temporary emigration where individuals could be present on site but remained undetected due to a lack of emitted vocal or visual cues. In contrast, temporal replicates across broader time scales, used in this study, mainly account for spatial temporary emigration instead.

In this manuscript, we applied the developed IDS model to a structured and semi-structured dataset, EPOC-ODF and EPOC, collected over three French regions under distinct data collection schemes. We compared ecological and observation parameters estimates from the IDS model to those obtained from a HDS model calibrated using only data collected by EPOC-ODF to test if data integration could lead to improvement in the accuracy of estimated parameters, i.e. reduction of their uncertainties. In addition, we conducted a simulation study aiming (i) to assess model identifiability, i.e., its capabilities to accurately estimate parameters; and (ii) to test potential improvement in estimated accuracy over multiple ranges of variation of simulated species availability, detectability and sampling scenarios.

Material and methods

Simulation study 1: model identifiability

For simulation study 1, we generated 1000 cases each consisting of a structured dataset, with 9 temporal replicates, collected over 200 sites and a semi-structured dataset containing 1000 sites with single visits over one season (Fig. 1). For each case, we randomly generated sets of parameters related to the ecological and observation processes, with (\({\beta }_{0}\)) species mean abundance, (\(\beta\)) effect of covariate \({X}_{i}\) on species abundance; (\({\varphi }_{0}^{DSopen};{\varphi }_{0}^{DS}\)) depicting mean species availability estimated by, respectively the structured and semi-structured dataset; (\(\gamma\)) effect of covariates \({U}_{i,j}\) and \({V}_{i}\) over species availability; (\({\sigma }_{0}\)) mean species detectability and (\(\alpha\)) effect of covariate \({Z}_{i,j}\) over species detectability, see Box 1 and Eq. (1). We also included residual errors on species abundance and species detectability, respectively (\({\varepsilon }_{i}^{abund}\); \({\varepsilon }_{i}^{det}\)) generated from a normal distribution of mean 0 and standard deviation (\({\sigma }_{{\varepsilon }^{abund}}\); \({\sigma }_{{\varepsilon }^{det}}\)).

Schematic representation of the simulation study design. We simulated 1000 datasets (structured and semi-structured) using the same set of simulated parameters across the two simulation studies. We simulated distinct detection probabilities \({\varphi }_{0}^{DSopen}\) and \({\varphi }_{0}^{DS}\) for each sampling design aiming to mimic a protocol effect.

We used an altered version of the function simHDSopen from AHMbook45 to simulate the datasets. All models were fitted using JAGS 4.3.146 through the jagsUI47 R package, while MCMC samples were retrieved using mcmcoutput48. See appendix S1 for MCMC parameters and priors used for simulation and case study.

Simulation study 2: estimates accuracy across different sampling scenarios

In simulation study 2, we aimed to assess improvement in accuracy of estimated parameters through data integration across multiple sampling scenarios. We used the same 1000 cases generated in simulation study 1, but varied the number of structured sites (ranging from 50 to 300) and semi-structured lists. The latter was determined by the multiplication of the number of structured sites, using a ratio ranging from 1 to 6. We defined ranges of the number of structured sites and ratio of added semi-structured lists based on the proportion of sampling schemes in our case study, see Fig. 2 and appendix S2. Inference improvement was associated with a reduction of uncertainty (i.e. reduction of the posterior distribution spread of estimated parameters using the 95% credible intervals CRI).

We calibrated a linear model of the log-transformed CRI width to assess if its reduction was affected by factors such as the model formulation used (either HDS or IDS) or estimated parameters. As we expect that model formulation could benefit from the number of input data, we included an interaction between model formulation and the simulated sampling design, i.e. the number of simulated structured sites and the ratio of added semi-structured sites. As the response variable of our intended model is derived from simulation results, we conducted a bootstrap to assess variation of CRI reduction through resamples over simulated cases and their associated parameters. Confidence intervals were estimated using 100 linear models, each based on resamples of 250 from converging IDS and HDS models.

Case study

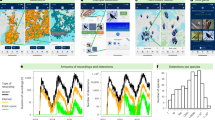

We relied on EPOC-ODF (Structured Estimation of Common Bird Population Size) and EPOC (Estimation of Common Bird Population Size) citizen science schemes data collected over 2021–2023 breeding seasons. These two schemes consist of 5-min point count completed checklists, during which observers point locations of detected individuals using the mobile app NaturaList49. Observation distances between observers and detected individuals are measured through GIS (Geographic Information System) using observers location determined by GPS. We used data from 31 bird species collected during their breeding season over 2021–2023 across three French regions (Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, Nouvelle-Aquitaine and Normandie). These regional datasets differ in terms of data quantity providing diverse distributions of structured and semi-structured data collections (Fig. 2.).

The EPOC scheme does not constrain observers to pre-selected sites, nor require repeated visits whereas, for EPOC-ODF, survey locations are randomly selected from a systematic grid and have to be visited three times during the breeding season, each session consisting of three successive 5-min point counts. For the semi-structured dataset (EPOC), we applied a spatial filter to select EPOC lists collected at least two kilometres away from sites with temporal replicates (EPOC-ODF) and other EPOC lists, see appendix S2. For each species, we calibrated a HDS model, using only data collected by the EPOC-ODF schemes and an IDS model using data collected by both schemes.

Bird species selection was based upon targeted species from the two schemes33 and had a sufficient number of observations, at least detected once at 20 distinct EPOC-ODF sites, in each region. We applied a temporal filter that considered both observed bird activities during the breeding season and expert knowledge to define the breeding phenology of each targeted species and exclude potential early or late migrants. For each species, we applied a right-side truncation of 5% over the observation distance to remove extreme distance values for model robustness50.

We modelled the population size of a site \({M}_{i}\) using a Zero-inflated Poisson with parameter \({\mu }_{i}\) (Fig. 3):

The expected species abundance parameter (\({\lambda }_{i}\)) was modelled using reduced habitat51 and bioclimatic52 covariates obtained through PCA33.

The zero-inflation parameter (\({\omega }_{i}\)) corresponds to site suitability depicted by a Bernoulli process with the probability (\({\rho }_{i}\)) of a site being considered unsuitable. We modelled \({\rho }_{i}\) in regards to site ecoregions, as a categorical variable53 and its spatial continuity54. We also included a site random effect for abundance (\({\varepsilon }_{i}^{abund}\)).

From the sampling scheme and temporal intervals between EPOC-ODF sessions, we considered that species availability primarily reflected spatial temporary emigration, due to migratory arrivals and departures during breeding seasons, potentially affecting the number of individuals potentially present on sites during surveys. Consequently, we modelled the probability of an individual being available for detection (\({\varphi }_{i,j}\)) using covariates such as hour from sunrise and julian date with quadratic effect to represent birds’ phenology across the breeding season. In the IDS model, we included a categorical covariate (\({\gamma }^{cat}\)) to account for variations in species availability due to the difference of temporal sampling over breeding seasons of the two schemes.

For species detectability, we used a half-normal detection function with parameter (\({\sigma }_{i,j}\)), where we modelled observers detection probabilities in regards to observed distances using categorical variables describing the habitat over four categories (Agricultural, Forest, Open and Urban;33) as well as the distance between their GPS locations and the nearest road55. For the IDS model, we considered two distinct intercepts allowing calibration of two separate detection functions, one for each dataset.

For species availability and detectability; we accounted for the study design of the structured dataset by implementing random effects over each session (\({\varepsilon }_{i,j}^{avail}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{i,j}^{det}\)) while also adding observers random effect over surveyed sites or lists (\({\eta }_{i}^{avail}\) and \({\eta }_{i}^{det}\)), as one observer can partake in both CS schemes, see appendix S1 for used priors.

Directed acyclic graph (DAG) representation of the hierarchical model. Observed and latent variables are represented using solid squares and dotted circles respectively. Arrows depicted links between parameters and covariates. Estimated coefficients are depicted on the side of covariates. We include the protocol origin as a categorical covariate, represented by a red box, solely for the IDS model. Each sub-process is represented by distinctive colours and pictograms, from left-to-right and up-to-down we depicted processes (i) describing variation of species abundance across space in relation to habitat covariates; (ii) representing sites’ probability of being considered unsuitable for modelled specie; (iii) assessing species probability of being exposed to sampling occasions and (iv) depicting species probability of being detected given its observation distance.

We fitted two linear mixed-effects models for assessing CRI reduction and shift in means of estimated parameters between the IDS and HDS. For both linear models, we considered a fixed effect of estimated parameters and included an interaction between model formulation and studied regions. We also added nested random effects over species and studied regions to account for specific species response for each region. Models were fitted using lme456. We used emmeans57 to estimate marginal means from the linear model and pairwise post hoc multiple comparisons. For the case study analysis, we removed (\({\gamma }^{cat}\)) and (\({\delta }^{cat}\)) parameters from comparison as the \({\gamma }^{cat}\) is not estimated in the HDS formulation and \({\delta }^{cat}\) parameters varied across studied regions.

Results

Simulation study

Simulation study 1

For simulation study 1, 861 out of 1000 simulated datasets resulted in converging models. Overall, the IDS model demonstrated its ability to accurately estimate the parameters for both the ecological and observation processes. While \({\varphi }_{0}^{DSopen}\), \({\varphi }_{0}^{DS}\), \({\sigma }_{{\varepsilon }^{abund}}\) and \({\sigma }_{{\varepsilon }^{det}}\) parameters appeared to have lower precision, all parameters had a coefficient of correlation (R2) above 0.85 between their simulated and estimated values (Fig. 4; S4.1). We also see that estimation of \({\beta }_{0}\) were centered over the generated value across all simulation. See appendix S3 for an analysis of model convergence of simulation studies.

Identifiability plot of converged model for the simulation study 1 for \({\varphi }_{0}^{DSopen}\); \({\varphi }_{0}^{DS}\); \({\sigma }_{ 0}\); \(\beta\); \({\beta }_{0}\) and their associated linear regression (dotted red line) R2 values. Accurate parameter identification is represented by a dotted blue line. The \({\beta }_{0}\) parameter is depicted as a histogram of estimated values, as we didn’t vary it across simulations. See appendix S4 for identifiability plots of the other generated parameters.

Simulation study 2

For simulation study 2, out of 1000 simulated datasets, we had 892 converging models using the HDS formulation and 930 converging models using the IDS formulation. There were no signs of major bias between simulated and the mean of parameter estimates considered (Fig. 5). Bootstrap resamples were based on 844 converging models for both the HDS and IDS formulation. We obtained a considerable reduction of CRI width across all estimated parameters for the IDS model (Fig. 6a). Overall, the IDS and the HDS models produced narrower CRI for available and more easily detectable species, however, the IDS model produced narrower CRI, for equivalent species availability-detectability profiles simulated than the HDS (Fig. 6b). The number of structured sites, i.e. including temporal replicates, was correlated with a reduction of CRI width for both models (Fig. 6c), although the IDS model CRI reduction was also correlated with an increasing proportion of semi-structured sites added to the calibration dataset (Fig. 6c). While the increasing proportion of semi-structured sites added to the calibration dataset had no substantial effect on the HDS model, we found an important correlation to a CRI reduction for the IDS model (Fig. 6c). See Appendix S6 for a comparison of CRI reduction in simulation study 2, where three temporal replicates were considered instead of nine.

Boxplot of differences (simulated—estimated) across mean estimated parameters for the HDS and IDS models. Parameters are represented in their respective scale (log or logit). Accurate estimation, i.e. no bias, is depicted by the dotted line. \({\varphi }_{0}^{DS}\) and standard deviations of residual errors of the semi-structured schemes (DS) were only estimated in the IDS model.

Marginal plot the simulation study 2 representing credible intervals (CRI) width obtained from the HDS and IDS models over 844 simulations. (a) Average CRI and their associated bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs), depicted by vertical density plots, over simulated parameters. (b) CRI average responses and CIs over simulated species availability (\({\varphi }_{0}^{DSopen}\)) and detectability (\({\sigma }_{0}\)) continuums on natural scales. Species availability averaged across multiple classes (0.05, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 0.95 detection probability) are depicted by colour-graded lines. (c) CRI average responses and CIs over multiple data collection cases. Ratio of semi-structured data (without temporal replicates) averaged over three classes (1,3 and 6) are depicted by colour-graded lines. Each dot (a) and line (b,c) correspond to a model marginal response from a bootstrapped resample consisting of 250 randomly selected converged models, allowing visualisation of the response signal CIs. For visual comparison between the HDS and the IDS estimates accuracy, we plotted CRI responses, grey ribbons, depicting the case of simulated species with high mean detectability (\({\sigma }_{0}\) = 200 m) and high probability of being available (\({\varphi }_{0}^{DSopen}\) = 0.95) surveyed over 100 sites with temporal replicates and six times the number of added semi-structured sites (c), depicted with vertical lines. Lower and upper bounds of the rectangles correspond to minimal and maximal estimated CRI width values.

Case study

Marginal effect plots from the linear model (Fig. 7) showed that Credible Intervals (CRI) were slightly wider for Normandie (Nor), the region with fewer structured sites and semi-structured sites than Bourgogne-Franche-Comté (BFC), the region with a few numbers of structured sites and a large number of semi-structured sites, and Nouvelle-Aquitaine (NvA), the region with a larger number of semi-structured sites (Fig. 2). While there were no considerable differences (indicated by an overlap of marginal response confidence intervals) between the HDS and IDS CRI for NvA and Nor, CRI from the IDS model were considerably narrower than the HDS ones for all estimated parameters in BFC (Fig. 7 and appendix S5). Pairwise comparison of marginal means showed no signs of significant differences (p-values > 0.05) between the HDS and IDS mean estimated parameters across all monitored parameters and studied regions. Squared-GVIFs (Generalised Variance-Inflation Factor; Ref.58), measured using car R package59, were less than 4, showing no signs of multicollinearity for the terms used in each model.

Marginal effect plots of CRI widths of estimated parameters and their associated CIs, in regards to the model (IDS in blue and HDS in red) and French regions (Nor: Normandie; NvA: Nouvelle-Aquitaine and BFC: Bourgogne-Franche-Comté). Coefficients of habitat effects on species abundance (\({\beta }_{1\to 6}\)) are depicted to the left of the vertical black line, while mean abundance (\({\beta }_{0}\)) is represented on the right. Significant gaps of averaged mean estimated parameters between models are highlighted with an asterisk. See appendix S5 for additional marginal effect plots for parameters associated with suitability, availability and detectability.

Discussion

The present work brings new evidence that Integrated Distance Sampling (IDS) models can accurately identify parameters of a complex ecological process and expand their application accounting for species availability determined through repeated visits. Moreover, it also shows that data integration improves ecological inference, through the reduction of credible intervals (CRI) width, for all parameters of the studied ecological process, across multiple sampling design scenarios and species availability-detectability continuums. Results from the case study further strengthen the simulation study, by showing that this reduction of CRI span without significant variations of estimated mean parameters depends on the ratio of structured and semi-structured data used for each case study.

In recent years, there has been an increase in the interest for integrated models26,27 due to their efficiency in reducing potential biases inherent to a single dataset60 and allowing reliance on automated and non-invasive data collection methods61,62. Data integration through joint likelihood63 still has potential drawbacks when temporal and/or spatial mismatches, corresponding to discontinuity between dataset timeframes and spatial heterogeneity, are unaccounted for. Such mismatches could lead to biased inferences where the sampled timeframes and/or regions do not correctly represent the ecological process of interest63,64.

In our simulation studies, we did not include spatial bias in data collection, which could potentially misrepresent citizen science spatial sampling bias65. We accommodated this mismatch in the case study through a spatial filter over the semi-structured dataset based upon the 2 × 2 km systematic grid resolution of the structured scheme. This resulted in an important decrease in available data from the semi-structured dataset (see appendix S2) that could be resolved through random effects in the model27. In our case, we could consider distinct spatial subsets of the semi-structured dataset and implement them into a random effect structure encompassing the modelled sub-processes of the integrated model.

While hierarchical models offer a viable option to disentangle variations due to the observation process from the variations originating from the ecological process of interest9, the trade-off between data specificities and data quantity can limit their applications. Data integration corresponds to a valuable option to increase the number of available data to help calibrate such models. Data integration also needs to account for sampling schemes specificities and their potential effect on estimated parameters. For instance, the variation of species availability in regards to list duration between standardised schemes and non-standardised schemes with varying durations38. Options to calibrate integrated hierarchical models exist in a frequentist framework38 allowing fast computation. However, given the types of available data and ecological processes of interest, data integration is prone to rely on Bayesian frameworks. Bayesian computation is based on Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) techniques which are computationally intensive66. Novel approaches exist such as Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (INLA) or Bayesian emulation67,68 allowing efficient computation and facilitating implementation of spatial components69.

Integrated models could represent an important tool for macro-ecology related studies, spanning across large spatial scales27 or requiring multiple institutions to coordinate data collection70,71. It could be used, for instance, in the study of bird populations across Europe from the pan-european common bird monitoring (PECBMS), which gathers data from point count, line transect, or territory mapping schemes across 28 countries and varying numbers of fieldworkers72, while taking account of country discrepancies in sampling design, sampling effort or varying starting period that could alter estimation of long-term trend73. The joint analysis of multiple data sources, notably through the use of data collected upon schemes lacking design-based methodology74, could represent a substantial increase in the quantity of data available for the study of cryptic species75,76 and improve assessment of migratory patterns over large spatial scales77. It represents an influx of data for the estimation of ecological processes of interest27, potentially reducing the sampling effort of robust designs. For instance, the number of temporal replicates considered in simulation studies and case study exceeds that of most commonly used schemes. To assess data integration utility beyond our specific case, we conducted an additional simulation study considering a structured scheme composed of three temporal replicates instead of nine (see appendix S6). Comparison of the HDS and IDS formulations over both temporal replicate quantities revealed that data integration had a greater effect in parameter accuracy when applied to the less demanding structured survey. However, it remained less accurate than estimates derived from using only data collected from the structured scheme with nine temporal replicates (Figure S6.1–3). Before their implementation, we highly recommend assessing whether ‘lessen’ structured sampling designs developed in a data integration context are still capable of estimating the targeted ecological parameters or only partially, using power analysis78 and assessment of integrated models identifiability via simulations79.

Our results highlight the benefits of relying on statistical frameworks such as Integrated Models capable of improving estimates accuracy through expansion of usable data collected from structured and semi-structured surveys. While our simulation results showed a constant reduction of estimates uncertainty, results from field surveys in three distinct French regions, depicting distinct ratios in quantity of structured and semi-structured data, showed that this improvement is case-dependant and significantly reduced estimates uncertainty with a low quantity of structured data and high quantity of semi-structured data. While we advocate for thorough planning before sampling, this suggests that Integrated Models could represent a conceivable alternative in case of insufficient collection from structured surveys and could also greatly benefit from data collected by citizen science schemes.

Data availability

Scripts, BUGS model files and data for simulation and case studies replications are available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11452853

References

Blondel, J., Ferry, C. & Frochot, B. Point counts with unlimited distance. Stud. Avian Biol. (1981).

Yoccoz, N. G., Nichols, J. D. & Boulinier, T. Monitoring of biological diversity in space and time. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 446–453 (2001).

Kellner, K. F. & Swihart, R. K. Accounting for imperfect detection in ecology: A quantitative review. PLoS One 9, e111436 (2014).

Burnham, K. P. Summarizing remarks: Environmental influences. Stud. Avian Biol. 6, 324–325 (1981).

Thompson, W. L. Towards reliable bird surveys: Accounting for individuals present but not detected. Auk 119, 18–25 (2002).

Lehikoinen, A. Climate change, phenology and species detectability in a monitoring scheme. Popul. Ecol. 55, 315–323 (2013).

Devictor, V., Whittaker, R. J. & Beltrame, C. Beyond scarcity: citizen science programmes as useful tools for conservation biogeography. Divers. Distrib. 16, 354–362 (2010).

Castagneyrol, B. et al. Can school children support ecological research? Lessons from the Oak bodyguard citizen science project. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 5 (2020).

Guillera-Arroita, G. Modelling of species distributions, range dynamics and communities under imperfect detection: Advances, challenges and opportunities. Ecography 40, 281–295 (2017).

Royle, J. A. & Dorazio, R. M. Hierarchical modeling and inference in ecology: The analysis of data from populations, metapopulations and communities. https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/5200344 (2008).

Nichols, J. D., Thomas, L. & Conn, P. B. In Model. Demogr. Process. Mark. Popul. (eds. Thomson, D. L., Cooch, E. G. & Conroy, M. J.), 201–235 (Springer US, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-78151-8_9

Mizel, J. D., Schmidt, J. H. & Lindberg, M. S. Accommodating temporary emigration in spatial distance sampling models. J. Appl. Ecol. 55, 1456–1464 (2018).

Kéry, M. & Royle, J. A. Applied Hierarchical Modeling in Ecology: Analysis of Distribution, Abundance and Species Richness in R and BUGS: Volume 1: Prelude and Static Models (Academic Press, 2016).

King, R. Statistical ecology. Annu. Rev. Stat. Appl. 1, 401–426 (2014).

MacKenzie, D. I. et al. Estimating site occupancy rates when detection probabilities are less than one. Ecology 83, 2248–2255 (2002).

Sollmann, R., Gardner, B., Williams, K. A., Gilbert, A. T. & Veit, R. R. A hierarchical distance sampling model to estimate abundance and covariate associations of species and communities. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 529–537 (2016).

Chandler, R. B., Royle, J. A. & King, D. I. Inference about density and temporary emigration in unmarked populations. Ecology 92, 1429–1435 (2011).

Gimenez, O. et al. State-space modelling of data on marked individuals. Ecol. Model. 206, 431–438 (2007).

Sullivan, B. L. et al. eBird: A citizen-based bird observation network in the biological sciences. Biol. Conserv. 142, 2282–2292 (2009).

Bonney, R. et al. Citizen science: A developing tool for expanding science knowledge and scientific literacy. Bioscience 59, 977–984 (2009).

Hochachka, W. M. et al. Data-intensive science applied to broad-scale citizen science. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 130–137 (2012).

Johnston, A. et al. Analytical guidelines to increase the value of community science data: An example using eBird data to estimate species distributions. Divers. Distrib. 27, 1265–1277 (2021).

Bayraktarov, E. et al. Do Big Unstructured biodiversity data mean more knowledge? Front. Ecol. Evol. 6 (2019).

Johnston, A., Matechou, E. & Dennis, E. B. Outstanding challenges and future directions for biodiversity monitoring using citizen science data. Methods Ecol. Evol. (2022).

Schaub, M. & Abadi, F. Integrated population models: A novel analysis framework for deeper insights into population dynamics. J. Ornithol. 152, 227–237 (2011).

Fletcher, R. J. et al. A practical guide for combining data to model species distributions. Ecology 100, e02710 (2019).

Zipkin, E. F. et al. Addressing data integration challenges to link ecological processes across scales. Front. Ecol. Environ. 19, 30–38 (2021).

Besbeas, P., Freeman, S. N., Morgan, B. J. T. & Catchpole, E. A. Integrating mark-recapture-recovery and census data to estimate animal abundance and demographic parameters. Biometrics 58, 540–547 (2002).

Schaub, M. Popul. Ecol. Pract. 215–236 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2020).

Keil, P., Wilson, A. M. & Jetz, W. Uncertainty, priors, autocorrelation and disparate data in downscaling of species distributions. Divers. Distrib. 20, 797–812 (2014).

Issa, N. & Muller, Y. Atlas des oiseaux de France métropolitaine: Nidification et présence hivernale (DELACHAUX, 2015).

Roché, J.-E., Muller, Y. & Siblet, J.-P. Une méthode simple pour estimer les populations d’oiseaux communs nicheurs en France. Alauda 81, 241–268 (2013).

Nabias, J. et al. Reassessment of French breeding bird population sizes using citizen science and accounting for species detectability. PeerJ 12, e17889 (2024).

Kelling, S. et al. Using semistructured surveys to improve citizen science data for monitoring biodiversity. Bioscience 69, 170–179 (2019).

Mackenzie, D. I. & Royle, J. A. Designing occupancy studies: General advice and allocating survey effort. J. Appl. Ecol. 42, 1105–1114 (2005).

Lauret, V., Labach, H., Authier, M. & Gimenez, O. Using single visits into integrated occupancy models to make the most of existing monitoring programs. Ecology 102, e03535 (2021).

von Hirschheydt, G., Stofer, S. & Kéry, M. “Mixed” occupancy designs: When do additional single-visit data improve the inferences from standard multi-visit models?. Basic Appl. Ecol. 67, 61–69 (2023).

Kéry, M. et al. Integrated distance sampling models for simple point counts. Ecology 105, e4292 (2024).

Miller, D. A. W., Pacifici, K., Sanderlin, J. S. & Reich, B. J. The recent past and promising future for data integration methods to estimate species’ distributions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 10, 22–37 (2019).

Emlen, J. T. Estimating breeding season bird densities from transect counts. Auk 94, 455–468 (1977).

Andriolo, A. et al. The first aerial survey to estimate abundance of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the breeding ground off Brazil (Breeding Stock A). J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 8, 307–311 (2006).

Manning, J. A. Factors affecting detection probability of burrowing owls in southwest agroecosystem environments. J. Wildl. Manag. 75, 1558–1567 (2011).

Kéry, M. & Royle, J. A. Applied Hierarchical Modeling in Ecology: Analysis of Distribution, Abundance and Species Richness in R and BUGS: Volume 2: Dynamic and Advanced Models (Academic Press, 2020).

Buckland, S. T., Rexstad, E. A., Marques, T. A. & Oedekoven, C. S. Distance Sampling: Methods and Applications, Methods in Statistical Ecology (Springer International Publishing, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19219-2.

Kéry, M., Royle, A. & Meredith, M. AHMbook: Functions and data for the book ‘Applied Hierarchical Modeling in Ecology’ Vols 1 and 2. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/AHMbook/index.html (2023).

Plummer, M. JAGS: A program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. In Proc. 3rd Int. Workshop Distrib. Stat. Comput. (2003).

Kellner, K. & Meredith, M. jagsUI: A wrapper around ‘rjags’ to Streamline ‘JAGS’ Analyses. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/jagsUI/index.html (2021)

Juat, N., Meredith, M. & Kruschke, J. mcmcOutput: functions to store, manipulate and display Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Output. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mcmcOutput/index.html (2022)

LPO France. Oiseaux de France: Fiche tutoriel. https://oiseauxdefrance.org/get-involved/Tuto-EPOC-ODF.pdf

Buckland, S. T. et al. Introduction to Distance Sampling: Estimating Abundance of Biological Populations (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Thierion, V., Vincent, A. & Valero, S. Theia OSO Land Cover Map 2020. 10.5281/zenodo.6538861 (2022).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315 (2017).

IGN. Sylvoécorégions - Cartographie des sylvoécorégions. https://geo.data.gouv.fr/fr/datasets/a40c533b984bdcd33d8a38f2430a117672395bc0. (2011)

Guetté, A., Carruthers-Jones, J. & Carver, S. J. Projet CARTNAT Cartographie de la Naturalité (2021).

Cote, C., Troncon, C., Troncon, C. & Troncon, C. ROUTE 500® Version 3.0 - Descriptif de contenu. 27 (2021).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Lenth, R. V. et al. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.html (2024).

Fox, J. & Monette, G. Generalized collinearity diagnostics. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 87, 178–183 (1992).

Fox, J. et al. car: Companion to applied regression. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/car/index.html (2023).

Zipkin, E. F., Inouye, B. D. & Beissinger, S. R. Innovations in data integration for modeling populations. Ecology 100, 1–3 (2019).

Doser, J. W., Finley, A. O., Weed, A. S. & Zipkin, E. F. Integrating automated acoustic vocalization data and point count surveys for estimation of bird abundance. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 1040–1049 (2021).

Pavanato Julião, H. Development of integrated distance sampling models. https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/handle/10523/1249 (2021).

Isaac, N. J. B. et al. Data integration for large-scale models of species distributions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 35, 56–67 (2020).

Powney, G. D., Preston, C. D., Purvis, A., Van Landuyt, W. & Roy, D. B. Can trait-based analyses of changes in species distribution be transferred to new geographic areas?. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 23, 1009–1018 (2014).

Johnston, A., Moran, N., Musgrove, A., Fink, D. & Baillie, S. R. Estimating species distributions from spatially biased citizen science data. Ecol. Model. 422, 108927 (2020).

Dorazio, R. M. Bayesian data analysis in population ecology: Motivations, methods, and benefits. Popul. Ecol. 58, 31–44 (2016).

Rue, H. et al. Bayesian computing with INLA: A review. Annu. Rev. Stat. Its Appl. 4, 395–421 (2017).

Fer, I. et al. Linking big models to big data: efficient ecosystem model calibration through Bayesian model emulation. Biogeosciences 15, 5801–5830 (2018).

Blangiardo, M., Cameletti, M., Baio, G. & Rue, H. Spatial and spatio-temporal models with R-INLA. Spat. Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol. 7, 39–55 (2013).

Navarro, L. M. et al. Monitoring biodiversity change through effective global coordination. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 29, 158–169 (2017).

Silva del Pozo, M., Body, G., Rerig, G. & Basille, M. Guide on harmonising biodiversity monitoring protocols across scales. 60 (Biodiversa+, 2023). <https://www.biodiversa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Biodiversa_Best-practices_2023_v5_WEB.pdf.

Brlík, V. et al. Long-term and large-scale multispecies dataset tracking population changes of common European breeding birds. Sci. Data 8, 21 (2021).

Duchenne, F. et al. Controversy over the decline of arthropods: A matter of temporal baseline?. Peer Community J. https://doi.org/10.24072/pcjournal.131 (2022).

Farr, M. T., Zylstra, E. R., Ries, L. & Zipkin, E. F. Overcoming data gaps using integrated models to estimate migratory species’ dynamics during cryptic periods of the annual cycle. Methods Ecol. Evol. 15, 413–426 (2024).

Martin, M. E. et al. An integrated spatial capture–recapture approach reveals the distribution of a cryptic carnivore in a protected area. Ecosphere 14, e4634 (2023).

Twining, J. P. et al. Integrating presence-only and detection/non-detection data to estimate distributions and expected abundance of difficult-to-monitor species on a landscape-scale. J. Appl. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14633 (2024).

Meehan, T. D. et al. Integrating data types to estimate spatial patterns of avian migration across the Western Hemisphere. Ecol. Appl. 32, e2679 (2022).

Guillera-Arroita, G. & Lahoz-Monfort, J. J. Designing studies to detect differences in species occupancy: power analysis under imperfect detection. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 860–869 (2012).

Ogle, K. & Barber, J. J. Ensuring identifiability in hierarchical mixed effects Bayesian models. Ecol. Appl. 30, e02159 (2020).

Acknowledgements

EPOC and EPOC-ODF schemes are supervised by LPO (Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux), the representative of Birdlife in France. We thank all participants and local coordinators from regional instances for contributing to data collection through faune-france.org, a collaborative online database. We would like to express our thanks to Benoit Fontaine for his comments on prior versions of the manuscript, we also would like to thank Marc Kéry, Niggel Yoccoz and an anonymous reviewer for their comments and suggestions that greatly improved this work. The IDS and HDS models were calibrated on the SACADO MCMeSU platform at Sorbonne Université in Paris – France.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided through OFB (Office Français de la Biodiversité), LPO and ANRT (Association Nationale Recherche Technologie; CIFRE grant, number: 2021/0305). The French Ministry of the Environment and OFB support the LPO through multi-year objectives agreements, in particular, to consolidate several EBV relating to birds, based on citizen science monitoring.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the current work. Study conceptualization was led by JN, RL, LB. Data collection management was performed by JD and LC. Analysis was carried out by JN and RL. Project administration was supervised by LB and LC. Writing was led by JN. Writing and reviews were conducted by JN and LB.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nabias, J., Lorrillière, R., Dupuy, J. et al. Improving national-scale breeding bird surveys with integrated distance sampling. Sci Rep 15, 18312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96787-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96787-w