Abstract

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is an aggressive cancer with 60% survival rate, high mortality, and morbidity. Leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and its receptor (LIF-R) are involved in the activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) pathway which has central involvement in the signalling pathways involved in important pathological processes including carcinogenesis and inflammation. STAT3 and its activators have shown prognostic significance in OSCC. The aim is to evaluate the immunohistochemical (IHC) expression of LIF and LIF-R proteins in OSCC. Four tissue microarrays (TMA) including OSCC (n = 95) and normal oral mucosa (NOM; n = 11) as control tissue were used in this study. FIJI software was for semi-quantitative analysis of IHC expression of LIF and LIF-R. Statistical analysis were performed using SPSS. LIF-R was expressed to a significantly higher extent in OSCC compared to NOM (p = 0.02) and LIF was expressed to a significantly higher extent in NOM compared to OSCC (p < 0.001) and in the buccal mucosa compared to the gingiva/alveolar mucosa (p = 0.022) and the lip vermilion (p = 0.17). No other significant differences were found in LIF and LIF-R expression when OSCC were compared according to site, grade, or stage. This is the first study to confirm the expression of LIF in OSCC and NOM. The biphasic lower expression of LIF and higher expression of LIF-R in OSCC may indicate a key point of differentiation between NOM and OSCC. The downregulation of LIF expression may be an indication of promotion towards malignancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is defined as a carcinoma with squamous differentiation arising from the mucosal epithelium of the oral cavity1. As such it refers to squamous malignancies arising in the oral mucosa: the lip vermilion, labial, buccal, floor of mouth, gingival, tongue, and hard palate mucosa2. OSCC is an aggressive cancer with approximately 50% survival rate, high mortality, and morbidity.

Signal transducer and activator or transcription-3 (STAT3) signalling pathway play a central role in several physiological and pathologic processes, including carcinogenesis3,4,5. Our recent findings show that STAT3 is expressed in higher extents in OSCC than normal oral mucosa (NOM) and that leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) receptor (LIF-R) is expressed in OSCC tissues and cell lines6. LIF and LIF-R are involved in several developmental and pathologic processes, and are known to activate STAT3 signalling. LIF and LIF-R have been investigated in several cancers, where they play different roles in promoting and inhibiting carcinogenesis and its progression7,8.

We set out to investigate the immunohistochemical expression of LIF and LIF-R in OSCC by the use of high-throughput tissue microarray (TMA) technology which included tissue cores of oral cancer, normal oral mucosa, and other oral and maxillofacial lesions accompanied by oral cancer site, histological diagnosis, grading, and staging data. TMA technology allows the concurrent investigation of hundreds of samples on one slide. This reduces processing variations, ensures consistency, and reduces cost of use of reagents6.

Materials and methods

Ethical approvalwas obtained from Charles Sturt University Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol no. H19142). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The commercially available tissues were collected by the vendor US Biomax, Inc. (USA) under the highest ethical standards with the donors being informed completely and with their informed consent, following standard medical care and protect the donors’ privacy. All human tissues were collected under HIPAA approved protocols.

The four commercially available OSCC TMAs obtained and used in this study included a total of 214 cases with 519 cores (minus overlapping cases) of 1–1.5 mm in diameter. The tissue cores included a range of oral malignant and benign neoplasms, reactive lesions, and normal control tissue. TMAs OR208, OR2081, OR803, and T271b were used in this study. The specifications of these TMAs are presented in (Table 1).

Rabbit polyclonal LIF-R (1:400 dilution; ABCAM, UK antibody no: ab101228 Lot: GR3325776-2) and rat monoclonal LIF [IMG39N7D10] (1:400 dilution; ABCAM, UK antibody no: ab138002 Lot: GR3325397-1) antibodies were obtained from Abcam (Auckland, New Zealand) and optimised using the heat retrieval I protocol with a Leica Bond III automated IHC/ISH Stainer (Leica Microsystems Pty Ltd, Mt Waverley, VIC, Australia) then counter-stained with haematoxylin. The antibody was removed from the process as a negative control and positive control tissues were used as shown in (Table 2).

The stained slides were then quality assured and scanned. Images of the cores were captured using Leica Web Viewer v12.4.4.5015 at 100x magnification for the purpose of image analysis. Each of the image files were renamed by the TMA and core position. Semi-quantitative analysis of the extent of immunohistochemical staining was undertaken using previously published protocols6,9 using Fiji (ImageJ) software10. Briefly, colour deconvolution was used followed by measuring the area of positive staining in the red channel where the threshold was adjusted using visual comparison with a series of representative RGB colour images. The resulting score represents the extent of the average positive staining of the tissue in each core.

The extent of immunohistochemical staining of the cores belonging to the same case, including overlapping cases across the four TMAs, were averaged to yield a mean score. The average extent of staining was compared across different groups of OSCC tissue and with NOM tissue using independent-sample t-tests or Mann-Whitney tests where variances were deemed unequal, and post-hoc Tukey’s test was used for pairwise analysis of the expression of LIF and LIF-R in different OSCC sites, stages, or grades as previously described6. Significance was set at the 0.05 level6. The statistical tests were performed using SPSS (IBM, version 25, NY, USA) and the graphs were plotted using Prism Graph Pad (Prism version 9 for Windows 64-bit, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, www.graphpad.com).

Results

Tissue samples from a total of 95 OSCC and 10 NOM cases, and 85 OSCC and 7 NOM cases were examined for the immunohistochemical expression of LIF-R and LIF proteins, respectively.

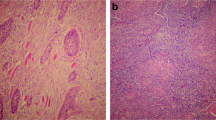

LIF-R was expressed to a significantly higher extent in OSCC compared to NOM (p = 0.02) and LIF was expressed to a significantly higher extent in NOM compared to OSCC (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

However, LIF-R expression was not significantly different in OSCC tissues when compared according to site (p = 0.168 for LIF-R; p = 0.024 for LIF), grade (p = 0.317 for LIF-R; p = 0.584 for LIF), or stage (p = 0.496 for LIF-R; p = 0.629 for LIF) (Tables 3, 4 and 5, Fig. 2).

Significantly higher expression of LIF was seen in the buccal mucosa compared to the gingiva/alveolar mucosa (p = 0.022) and the lip vermilion (p = 0.17) using Tukey’s posthoc test.

There were also no significant differences in the expression of LIF and LIF-R between intra-oral OSCCs and lip vermilion SCCs (LIF-R: Levene’s test p = 0.007, Mann-Whitney test p = 0.262; LIF: p = 0.22, Levene’s test p = 0.087).

The immunohistochemical expression of LIF-R and LIF proteins are shown in OSCC and NOM tissue. Significantly higher expression of LIF-R was seen in OSCC compared to NOM tissue (p = 0.02) and LIF in NOM compared to OSCC tissue (p < 0.001). The bars represent the average area of staining, and the error bars the standard error of the means.

Graphs showing the extent of LIF and LIF-R staining expressed in percentages. Apart from the significantly higher extent of LIF expression in buccal mucosa compared to gingival (p = 0.022) and lip vermilion (p = 0.17) OSCC, no significant differences were seen when comparing OSCC based on site, stage, or grade.

Discussion

The current study reports the immunohistochemical staining of LIF in OSCC and NOM. Two other studies have so far reported LIF expression in OSCC epithelial cells11,12, though one of them reported only weak LIF expression in OSCC cells but strong expression in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF)12. Experiments in both studies have shown that LIF signalling contributes to invasion and metastasis. In the first study, higher extents of immunohistochemical expression of LIF protein was shown to be associated with higher likelihood of regional metastases and also lower survival rates11 In the second study, immunohistochemical expression of LIF protein was detected in CAF and higher expression was associated with increased depth of invasion. In addition, antibodies targeted at LIF protein resulted in the inhibition of migration and invasion of OSCC in cell culture12.

Investigations of LIF and LIF-R expression in cancers have often yielded paradoxical results where they have shown pro-tumour effects in some and anti-tumour effects in others, which is reviewed in depth elsewhere8.This is not surprising due to the multitude effects of LIF/LIF-R signalling, which involve activation of a number of significant signalling pathways including MAPK, JAK/STAT, and PI(3)K, which ultimately lead to differentiation, maintenance, and survival, respectively of embryonic stem cells8,13. We and others have also previously reported the role of STAT-3 pathway upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in the suppression of the anti-tumour immune response6,8, which is another possible effect of LIF/LIF-R signalling in the context of cancer. It is also worth noting that the most commonly implicated pathway in LIF signalling in cancers is the JAK/STAT pathway, mainly STAT3. It is also important to recognise that the main activator of the STAT3 pathway is IL-6 and its receptor, both of which have already been investigated in a number of pathological processes, including cancer, and have even been used as targets for molecular therapy4,5,14.

In the current study, the expression pattern of LIF was significantly lower in OSCC than NOM whereas that of LIF-R was higher in OSCC. This biphasic pattern suggests a role of LIF/LIF-R signalling in differentiation indicated by LIF expression and loss of LIF expression seen in OSCC suggesting progression. This expression pattern and associated behaviour can be interpreted in relation to the expected natural biological behaviour of cancers, outlined in the seminal paper on the hallmarks of cancer15, which was updated in 2022 with the addition of new dimensions16, one of which – unlocking phenotypic plasticity, is most likely associated with the expression pattern of LIF/LIF-R observed in the current study and consistent with the role of LIF in stem cell differentiation. With unlimited proliferation potential and lack of sensitivity to inhibitory signals, tumour cells continue proliferation unchecked. This behaviour also affects differentiation where less differentiated or de-differentiated tumours are known to behave more aggressively.

Our qualitative observations have shown LIF expression in in almost the entire thickness of NOM in addition to areas of obvious squamous differentiation in OSCC tissues. This leads to the suggestion that LIF expression is associated with squamous differentiation and loss of LIF expression is associated with malignant progression. However, the study by Lin et al.11, which is the only other study that has reported LIF expression in OSCC epithelial cells, report that approximately half of the stage 4 cancers had low LIF expression despite those particular cancers having also lower rates of regional metastases. In our study, we did not find any correlation between cancer stage and extent of expression of LIF in OSCC. As such, it seems that the expression of LIF in OSCC is expectedly variable due to the heterogenous nature of OSCC. It is yet unknown whether the proportion of immortalised versus mortal OSCC cells influences the LIF expression and hence biological behaviour of these tumours.

Conclusions

The current study is one of the first few to confirm the expression of LIF in OSCC and NOM. The biphasic lower expression of LIF and higher expression of LIF-R in OSCC may indicate a key molecular tipping point related to differentiation versus proliferation in NOM and OSCC. The downregulation of LIF expression may be an indication of promotion towards malignancy. Further research is required to determine the mechanisms, effects, and significance of LIF downregulation in OSCC.

Data availability

The raw and supplemental data are found on Figshare using these private sharing links: Raw data - https://figshare.com/s/156bb561f7e65c1db1bb. Statistical tests - Site based analysis: https://figshare.com/s/59c2bdc7deed2cbd954b.

References

Lingen, M. et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma. In WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours. (ed Muller, S.) (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2022).

Yakin, M., Gavidi, R. O., Cox, B. & Rich, A. Oral cancer risk factors in new Zealand. N. Z. Med. J. 130, 30–38 (2017).

Yu, H. et al. Revisiting STAT3 signalling in cancer: new and unexpected biological functions. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 736–746 (2014).

Macha, M. A. et al. Prognostic significance of nuclear pSTAT3 in oral cancer. Head Neck 33, 482–489 (2011).

Aziz, M. H. et al. Protein kinase Cɛ mediates Stat3Ser727 phosphorylation, Stat3-regulated gene expression, and cell invasion in various human cancer cell lines through integration with MAPK cascade (RAF-1, MEK1/2, and ERK1/2). Oncogene 29, 3100–3109 (2010).

Yakin, M., Seo, B. & Rich, A. Tunicamycin-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress up-regulates tumour-promoting cytokines in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cytokine 120, 130–143 (2019).

Kamohara, H. et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor functions as a growth factor in pancreas carcinoma cells: involvement of regulation of LIF and its receptor expression. Int. J. Oncol. 30, 977–983 (2007).

Christianson, J., Oxford, J. T. & Jorcyk, C. L. Emerging perspectives on leukemia inhibitory factor and its receptor in cancer. Front. Oncol. 11, 693724 (2021).

Crowe, A. & Yue, W. Semi-quantitative determination of protein expression using immunohistochemistry staining and analysis: an integrated protocol. Bio Protocol 9. (2019).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Lin, T-A. et al. Role and mechanism of LIF in oral squamous cell carcinoma progression. J. Clin. Med. 9, 295 (2020).

Ohata, Y. et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor produced by fibroblasts within tumor stroma participates in invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One 13, e0191865 (2018).

Nicola, N. A. & Babon, J. J. Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). Cytokine Growth Fact. Rev. 26, 533–544 (2015).

Yedida, G. R., Nagini, S. & Mishra, R. The importance of oncogenic transcription factors for oral cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 116, 179–188 (2013).

Hanahan, D. & Robert Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011).

Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12, 31–46 (2022).

Funding

This project was funded by a Faculty of Science–Charles Sturt University Compact Seed Grant and the Oral Molecular and Immunopathology Research Group at Sir John Walsh Research Institute at the University of Otago. The project was conceived, funded, and approved during the first author’s appointment with Charles Sturt University while data acquisition and analysis, and manuscript preparation was completed during their appointment at the Adelaide Dental School at the University of Adelaide.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors, including Alison M. Rich, made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, revised the work critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.H.H. and B.S. were responsible for antibody optimisation, immunohistochemical staining, and scanning of the slides. M.Y. performed the image acquisition, analysis, initial interpretation of the data, and drafted the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the lead author used ResearchRabbitAI in order to locate similar work in the topic. The tool was not used to generate any text or content. Generative AI was not used to create any content.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yakin, M., Seo, B., Hussaini, H.M. et al. Immunohistochemical expression pattern of leukemia inhibitory factor and its receptor may mark a tipping point in the progression of oral cancer. Sci Rep 15, 35059 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96841-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96841-7