Abstract

In the last decade, the incidence of stroke among young adults has risen globally. The relevance of carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) and plaque in predicting ischemic stroke (IS) in this population remains uncertain. This study investigated the relationship between ultrasound-evaluated carotid wall properties and occurrence and severity of IS in young adults. Young adults (n = 147) aged 18–50 years with IS and 294 age- and sex-matched controls were included. Ultrasound-assessed variables included carotid atherosclerosis, perivascular adipose tissue, and arterial stiffness. Ultrasound parameters included IMT, plaque presence, extra-media thickness (EMT), and flow augmentation index (FAI). Multivariate and ROC curve analyses were conducted. All ultrasound parameters were elevated in the IS group. Carotid EMT and FAI were associated with IS, while IMT and plaque were not. The multivariate model combining carotid EMT and FAI showed a superior area under the curve compared to models incorporating either parameter alone. Plaque presence and increased EMT thickness correlated with higher scores on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Carotid EMT and FAI are independent vascular risk factors for IS in young adults. The potential of EMT and plaque presence as biomarkers for assessing disease severity warrants further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ischemic stroke (IS) is a significant cause of death and disability worldwide, impacting individuals across all age groups, from neonates to older individuals1. The global incidence of IS among young adults (aged 18–50 years) has surged by 40% over the past decade2. This significant increase suggests that traditional risk factors used to screen for IS may not fully apply to younger populations.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) are widely recommended for diagnosing cerebrovascular diseases3. As a screening tool, carotid ultrasound is ideal for detecting atherosclerosis. It is non-invasive and highly sensitive, with better spatial resolution compared to other methods. It is considerably less costly and can be performed at the bedside without requiring a specific location. These attributes make carotid ultrasound particularly suitable for large-scale screenings.

The common carotid artery (CCA) intima-media thickness (IMT) and the presence of carotid plaque, especially vulnerable plaque, are established predictors of ischemic stroke in extensive atherosclerosis of the large arteries4,5. Yet, most existing research focuses on older adults, typically those aged 60 years or older ;6,7 the applicability of these findings to younger adults remains uncertain. The impact of carotid perivascular adipose tissue and arterial stiffness on IS in young adults has been minimally explored despite their known roles in vascular dysfunction8,9. Studies have shown that ultrasound measurements of perivascular adipose tissue (extra-media thickness; EMT) relate to vascular aging and coronary artery disease10, while measurements of arterial stiffness (flow augmentation index; FAI) may be linked to minor cerebral vascular injuries11.

Therefore, we conducted a prospective observational case-control study to investigate carotid ultrasound parameters for identifying IS and their association with disease severity in young adults.

Methods

The ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University approved this study for medical research. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Informed written consent was obtained from each patient or their relatives before participation. We adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines.

Study design and participant recruitment

This prospective observational case-control study took place at the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University in Fuzhou, China, from March 2021 to May 2024. We recruited 147 patients with IS from the Department of Neurology, which includes the Main and the Binhai Campuses of the First Affiliated Hospital, designated as a National Regional Medical Center. Additionally, 294 control participants were recruited from the Health Management Center at these locations (Supplementary File 1, Fig. S1).

Patients with IS were diagnosed based on any sudden and persistent neurological deficit resulting from an infarction, confirmed by neuroimaging. Each patient underwent an etiological examination that included a comprehensive history and physical examination, as well as additional tests, encompassing a complete blood count, biochemistry, coagulation tests, a 24-h ECG, carotid ultrasound, transcranial Doppler, transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography, and CTA and MRA to assess extracranial and intracranial vessels3,12,13. The inclusion criteria were patients aged 18–50 years at the time of examination, with a definitive first occurrence, < 50% carotid stenosis, and complete imaging results. Exclusion criteria included IS in the posterior circulation, cerebral hemorrhages, coronary atherosclerotic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, mitral stenosis, cardiac thrombosis, prior carotid endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting, a family history of hypercholesterolemia, systemic vasculitis (including Takayasu arteritis, lupus vasculitis, and rheumatoid vasculitis), and abnormal kidney or hepatic function.

Control participants were matched with the IS group at a 2:1 ratio based on sex and age at the time of examination. Control participants were identified as those with at least one traditional risk factor (TRF) for IS during the same period as IS participants. Exclusion criteria for controls included cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral artery diseases; malignant tumors; history of head and neck surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy; a family history of hypercholesterolemia; systemic vasculitis (including Takayasu arteritis, lupus vasculitis, rheumatoid vasculitis); and abnormal kidney or hepatic function.

Demographic characteristics

During the enrollment process, we collected information from participants, including age at examination, sex, BMI, SBP, DBP, smoking status, and diabetes mellitus. Serum biochemical indicators, including TC, TG, LDL, and HDL, were also analyzed.

Ultrasound parameters measurement

Participants underwent vascular ultrasound examinations, with data collection occurring at least two hours after their last meal. They were advised to avoid coffee, tea, alcohol, and vigorous exercise for at least 12 h before the test.

Imaging of the common carotid artery was performed using a Resona 7 S/9 ultrasonic diagnostic instrument (Mindray, Shenzhen, China) with transducers of L14-5WU (5–14 MHz)/L15-3WU (3–15 MHz) and a Hi-Vision Preirus ultrasonic diagnostic instrument (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) with a transducer of L74M (5–13 MHz).

Intima-media thickness (IMT) measurement IMT is visualized as a double-line pattern on ultrasound, representing the lumen–intima and media–adventitia interfaces of the CCA in a longitudinal view (Fig. 1a)14. IMT was measured on the far wall of the CCA, at least 5 mm below the bifurcation, over a 10-mm length of a straight arterial segment. This segment needed to be plaque-free to ensure the high-quality image acquisition necessary for reproducible measurements. Three IMT measurements were taken at 1-mm increments along the far wall of the CCA, and the average of these measurements was calculated.

(a, b) Carotid ultrasound images were used to measure carotid atherosclerosis, perivascular adipose tissue, and stiffness. (a) The measurement of IMT demonstrates the distance between the short blue equal-like lines representing the lumen–intima interface and the media–adventitia interface at the 10-mm length segment starting 5 mm proximal to the bulb of the carotid artery. The measurement of EMT demonstrated the distance between the short, orange, equal-like lines representing the carotid media–adventitia interface and the jugular lumen at the segment where the carotid artery and jugular vein are closest. (b) The calculation method of FAI was defined as (Vsr−Ved)/(Vs−Ved). At least three common carotid artery flow velocity waveforms obtained from a stable area of the record were analyzed to determine the following parameters: peak systolic flow velocity (Vs); end-diastolic flow velocity (Ved); and peak flow velocity of the secondary rise in the common carotid flow velocity waveform (Vsr). EMT, extra-media thickness; IMT, intima-media thickness; FAI, flow augmentation index.

Extra-media thickness (EMT) measurement EMT was defined as the distance between the media-adventitia interface of the CCA and the lumen of the internal jugular vein (IJV). This measurement was manually taken on the near wall of the CCA in the longitudinal view at the segment where the IJV and CCA were the closest and visible, approximately 1–1.5 cm proximal to the carotid bulb (Fig. 1a)15. Three frames from each side were used for these measurements. The average of the EMT measurements from both sides was calculated.

Flow augmentation index (FAI) measurement FAI was calculated using at least three stable waveforms of standard carotid artery flow velocity. These waveforms allowed for the determination of the following parameters: peak systolic flow velocity (Vs), end-diastolic flow velocity (Ved), and the peak flow velocity of the secondary rise in the standard carotid flow velocity waveform (Vsr) (Fig. 1b)16. FAI was defined as (Vsr−Ved)/(Vs−Ved). Three frames from each side were used for these measurements. The average of the FAI measurements from both sides was computed.

The measurements were performed by ultrasonographers with over 10 years of experience in vascular ultrasound.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized using mean or median, as appropriate. The normality of continuous data was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage (%). Comparisons of non-parametric continuous variables were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test for two groups. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square (χ2) or Fisher’s exact tests when the expected value was less than 5.

Logistic regression was used to assess associations between carotid ultrasound parameters, TRFs, and IS. Linear regression was utilized to evaluate associations between carotid ultrasound parameters, TRFs, and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores in terms of disease severity.

The area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to assess the prognostic ability of carotid ultrasound parameters for IS in young adults.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 and GraphPad Prism 9.0. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study participants

A total of 441 participants were included in the study: 147 were case patients with IS, and 294 were control participants without IS. The median BMI for control participants was 25.3 (24.8–25.8) kg m–2, which was lower than that of patients with IS (P < 0.0001). TRFs, including SBP, DBP, diabetes mellitus, smoking, TC, TG, LDL, and HDL, were higher in patients with IS than in control participants (all P < 0.0001) (Table 1).

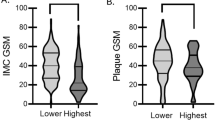

Comparison of carotid ultrasound parameters between patients with IS and control participants

In this study, the median IMT was 0.9 mm in patients with IS, significantly thicker than that in control participants (P < 0.0001). The frequency of plaque was also markedly higher in patients with IS than in control participants (P < 0.0001). The EMT in patients with IS was significantly thicker than that in control participants (P < 0.0001). The FAI of the former was considerably larger than that of the latter (P < 0.0001).

Association between carotid ultrasound parameters and TRFs and IS

In this study, carotid ultrasound parameters, including the presence of plaque, IMT, EMT, and FAI, were associated with young patients with IS according to univariable logistic regression (Table 2).

We also observed that TRFs, including high BMI, SBP, DBP, TC, TG, LDL levels, low HDL levels, diabetes mellitus, and smoking, were significantly associated with IS in young adults, as determined by univariate logistic regression analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed a significant association between high BMI, SBP, DBP, TC, LDL and HDL levels, and IS in young adults (Table 2).

After adjusting for BMI, SBP, DBP, TC, LDL, and HDL, both EMT and FAI remained significantly associated with young patients with IS in the multivariate logistic regression. However, no significant associations were observed between IMT or the presence of plaque and IS in young adults (Table 2).

Identifiable ability of carotid ultrasound parameters for young adults with IS

ROC analysis of EMT and FAI showed a large AUC for predicting IS in young adults, ranging from 0.800 to 0.900, with corresponding cut-off values of 0.98 mm and 0.48, respectively (Table 3). However, the sensitivity of EMT and the specificity of FAI were only 64.6% and 74.8%, respectively. The combination of EMT and FAI performed well in identifying IS in young adults, with an AUC of 0.907 (0.878–0.935) and improved sensitivity and specificity of 80.3% and 81.3%, respectively (Table 3; Fig. 2).

The receiver operating characteristic curve showed that the multivariate models of EMT and FAI can better predict IS in young adults with AUC, sensitivity, and specificity than univariate models of EMT or FAI. AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; EMT, extra-media thickness; FAI, flow augmentation index.

Association between carotid properties and disease severity in young adults with IS

We investigated the association between carotid properties assessed by ultrasound and disease severity in young patients with IS. We observed significant associations between the NIHSS score and the following carotid ultrasound parameters: the presence of plaque (β = 0.279, P = 0.001), IMT (β = 0.297, P < 0.0001), EMT (β = 0.546, P < 0.0001), and FAI (β = 0.516, P < 0.0001) (Table 4). Several traditional risk factors, including age at examination, BMI, and the presence of diabetes mellitus, were significantly associated with NIHSS scores in these young patients (all P < 0.05) (Table 4).

The multivariate linear regression model revealed that thicker EMT (β = 0.458, P < 0.0001), the presence of plaque (β = 0.166, P < 0.0001), and older age at examination (β = 0.456, P = 0.005) were significantly associated with higher NIHSS scores in young patients with IS (Table 4).

Discussion

This study provides a detailed assessment of the association of carotid atherosclerosis, stiffness, and perivascular adipose tissue in young adults with ischemic stroke (IS). We found that carotid atherosclerosis (i.e., presence of plaque) was not associated with IS in young patients, however, perivascular adipose tissue (i.e., EMT) and carotid stiffness (i.e., FAI) were associated with IS in young patients, independently of conventional vascular risk factors and carotid atherosclerosis. When combining FAI and EMT this association was even stronger. Additionally, EMT was associated with disease severity in young patients with IS.

The measurement of carotid EMT was first proposed by Skilton et al. as an ultrasound parameter to investigate the association of arterial adventitia with cardiovascular risk15. In this study, we observed that CCA EMT was a vascular risk factor for IS in young adults, with thicker EMT correlating with more severe ischemic stroke. The main component in the EMT region is considerable amounts of adipose tissue15. The perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) around the carotid artery is white adipose tissue8. The metabolic activity of PVAT may act systemically or locally17. During obesity and hypertension, the paracrine effects of PVAT, particularly on vascular tone and inflammation, are significantly altered. Cytokines and classical adipokines dysregulate critical genes involved in vascular redox balance, leading to endothelial dysfunction and vascular stiffness8. Our results suggest that increased EMT can be a surrogate marker of arterial dysfunction and a vascular risk factor for stroke in young adults. This information underscores the potential for targeted medical interventions for PVAT in preventing IS in young adults.

We observed an association between carotid stiffness and IS in young adults, which is consistent with previous findings18,19. Kozo Hirata et al. reported that flow waves exhibited a strong correlation with pressure waves, closely approximating the line of identity16. In our study, we used the FAI instead of the augmentation index (Aix), which is a recognized indicator for atherothrombotic strokes20, to calculate carotid stiffness. We found that FAI was significantly larger in patients with IS than in control participants. Junichiro Hashimoto et al. also reported that carotid FAI was associated with age, aortic stiffness, and cerebral white matter hyperintensities, suggesting that increased cerebral flow pulsations may cause microcerebrovascular injury21.

Hypertension is a traditional risk factor for IS. It exerts pulsatile shear stress on the carotid and cerebral microvasculature due to increased pulsatile flow velocity, leading to vascular wall remodeling and damage20,22,23. In this study, SBP and DBP were higher in the young adults with IS than in the control participants, reinforcing the relevance of hypertension as a risk factor for IS in young adults.

Previous studies have shown that CCA IMT and carotid plaque are conventional vascular risk factors for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults4,24,25,26. In our study, no association was observed between CCA IMT, carotid plaque, and IS in young adults (˂ 50 years). Although CCA IMT was thicker in the young adults with IS than in control participants, the median CCA IMT was 0.9 mm in the young patients with IS, which was lower than the reference values of 0.9–1.0 mm27,28. This suggests that CCA IMT may not be a useful indicator of increased risk of IS in young adults.

Regarding carotid plaque, Mathiesen et al. reported that carotid plaque was a strong predictor for first-ever ischemic stroke in a healthy population aged 25–84 years over a 10-year follow-up period29. Our findings in young adults were inconsistent with these results29. Although carotid plaque was more frequent in young adults with IS than in control participants, only 55.1% of patients with IS had carotid plaques. Multivariate regression analysis further suggested that carotid plaque was not an independent vascular risk factor for IS in young adults.

In studying IS disease severity, we observed that thicker EMT and the presence of carotid plaque were significantly associated with higher NIHSS scores, suggesting that atherosclerosis may not be the primary cause of IS in young patients but could exacerbate vascular damage. The inflammation of PVAT promotes the formation and deep invasion of microvessels from the adventitia into the carotid plaque, contributing to vulnerable plaque that could lead to multifocal IS8,30.

We also investigated the ability of CCA EMT and FAI to identify IS in young adults, advancing their clinical application. We found that their combined application demonstrated a strong ability to identify IS, as evidenced by an AUC of 0.907, with sensitivities and specificities of 80.3% and 81.3%, respectively, and cut-off values of 0.97 mm for EMT and 0.45 for FAI.

There are some limitations to our study. First, we employed a case-control design, which allows for the examination of associations; however, longitudinal studies are necessary to determine whether these associations indicate causal relationships. Second, although our study investigated the association between ultrasound parameters of carotid properties and disease severity in young adults with IS, the prognostic value of these ultrasound parameters in young patients with IS has not yet been explored. Third, this study is a single-center investigation with a small sample size, which may exclude young adults with carotid stenosis exceeding 50%, potentially leading to selection bias. Multi-center, large-sample studies are essential for validating the findings.

Conclusions

In summary, our study provides evidence that carotid properties are correlated with IS in young adults. Our findings emphasize the association between carotid PVAT, stiffness, and IS in this population. EMT and FAI, serving as ultrasound markers for PVAT and carotid stiffness, respectively, exhibit robust capabilities to identify IS in young adults. EMT and FAI can be easily and noninvasively quantified using ultrasound in a clinical setting.

Data availability

The dataset used in our study was not publicly available to ensure the privacy and confidentiality of the patients involved. Interested parties can request access to the dataset by contacting the corresponding authors.

References

Powers, W. J. et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 50, e344-e418. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000211 (2019).

Béjot, Y., Bailly, H., Durier, J. & Giroud, M. Epidemiology of stroke in Europe and trends for the 21st century. Presse Med. 45, e391–e398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2016.10.003 (2016).

Feske, S. K. Ischemic stroke. Am. J. Med. 134, 1457–1464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.07.027 (2021).

O’Leary, D. H. et al. Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular health study collaborative research group. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199901073400103 (1999).

Brunelli, N. et al. Carotid artery plaque progression: proposal of a new predictive score and role of carotid Intima-Media thickness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020758 (2022).

Kokubo, Y. et al. Impact of Intima-Media thickness progression in the common carotid arteries on the risk of incident cardiovascular disease in the suita study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e007720. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.007720 (2018).

Jin, S. et al. Differential value of intima thickness in ischaemic stroke due to large-artery atherosclerosis and small-vessel occlusion. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25, 9427–9433. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.16884 (2021).

Antoniades, C. et al. Perivascular adipose tissue as a source of therapeutic targets and clinical biomarkers. Eur. Heart J. 44, 3827–3844 (2023).

Regnault, V., Lacolley, P. & Laurent, S. Arterial stiffness: from basic primers to integrative physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 86, 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-042022-031925 (2024).

Haberka, M. & Gąsior, Z. A carotid extra-media thickness, PATIMA combined index and coronary artery disease: comparison with well-established indexes of carotid artery and fat depots. Atherosclerosis Nov. 243(1), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.09.022 (2015).

Hashimoto, J., Westerhof, B. E. & Ito, S. . Carotid flow augmentation, arterial aging, and cerebral white matter hyperintensities. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 38(12), 2843–2853. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311873 (2018).

Powers, W. J. Acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1917030 (2020).

Adams, H. P. Jr et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke 24, 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.24.1.35 (1993).

Touboul, P. J. et al. Mannheim carotid intima-media thickness and plaque consensus (2004-2006-2011). An update on behalf of the advisory board of the 3rd, 4th and 5th watching the risk symposia, at the 13th, 15th and 20th European stroke conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, Brussels, Belgium, 2006, and Hamburg, Germany, 2011. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 34, 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1159/000343145 (2012).

Skilton, M. R. et al. Noninvasive measurement of carotid extra-media thickness: associations with cardiovascular risk factors and intima-media thickness. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2, 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.09.013 (2009).

Hirata, K., Yaginuma, T., O’Rourke, M. F. & Kawakami, M. Age-related changes in carotid artery flow and pressure pulses: possible implications for cerebral microvascular disease. Stroke 37, 2552–2556. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000242289.20381.f4 (2006).

Verhagen, S. N. & Visseren, F. L. Perivascular adipose tissue as a cause of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 214, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.05.034 (2011).

van Sloten, T. T. et al. Carotid stiffness is associated with incident stroke: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66, 2116–2125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.888 (2015).

Webb, A. J. S. & Werring, D. J. New insights into cerebrovascular pathophysiology and hypertension. Stroke 53, 1054–1064. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035850 (2022).

Sakamoto, Y., Kimura, K., Aoki, J. & Shibazaki, K. The augmentation index as a useful indicator for predicting early symptom progression in patients with acute lacunar and atherothrombotic strokes. J. Neurol. Sci. 321, 54–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2012.07.049 (2012).

Hashimoto, J., Westerhof, B. E. & Ito, S. Carotid flow augmentation, arterial aging, and cerebral white matter hyperintensities. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 38, 2843–2853. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311873 (2018).

Cipolla, M. J., Liebeskind, D. S. & Chan, S. L. The importance of comorbidities in ischemic stroke: impact of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 38, 2129–2149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678X18800589 (2018).

Zhang, D. et al. Hemodynamics is associated with vessel wall remodeling in patients with middle cerebral artery stenosis. Eur. Radiol. 31, 5234–5242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-07607-w (2021).

Prati, P. et al. Carotid intima media thickness and plaques can predict the occurrence of ischemic cerebrovascular events. Stroke 39, 2470–2476. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.511584 (2008).

Parish, S. et al. Assessment of the role of carotid atherosclerosis in the association between major cardiovascular risk factors and ischemic stroke subtypes. JAMA Netw. Open. 2, e194873. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4873 (2019).

Xu, M. et al. The diagnostic value of radial and carotid intima thickness measured by High-Resolution ultrasound for ischemic stroke. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 34, 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2020.09.006 (2021).

College of sonographers affiliated to CMDA. Guideline for vascular ultrasound examination. Chin. J. Ultrasonogr. 18, 911–920. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1004-4477.2009.10.037 (2009).

Simova, I. Intima-media thickness: appropriate evaluation and proper measurement, described. E-J. ESC Counc. Cardiol. Pract. 13, 1 (2015).

Mathiesen, E. B. et al. Carotid plaque area and intima-media thickness in prediction of first-ever ischemic stroke: a 10-year follow-up of 6584 men and women: the Tromsø study. Stroke 42, 972–978. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.589754 (2011).

Saba, L. et al. Carotid Plaque-RADS: a novel stroke risk classification system. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 17, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2023.09.005 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the Leading Project Foundation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province (Grant No. 2020Y0024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X. L. and X. X. designed and founded the study; L. F. and Z. X. provided material of participants; J. C., X. L., X. W., and L. W. Obtained ultrasound data; J. X. and L. W. analyzed data; X. X. and B. G. interpreted the data; X. X. and B. G. wrote the manuscript; X. L., X. X., B. G, L. F., Z. X., J. X., L. W., J. C., X. L., X. W., and L. W. reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, X., Guo, B., Chen, J. et al. Association of carotid atherosclerosis, perivascular adipose tissue, and stiffness by ultrasound assessment in young adults with ischemic stroke. Sci Rep 15, 13106 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96975-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96975-8