Abstract

A Fe-modified black peanut shell biochar (Fe@BC) was fabricated using FeCl3 as a magnetic modifier, its sorption for Pb(II) in mixed Pb(II), Cu(II), Ni(II) solutions was examined. It was showed that Fe@BC had better adsorption for Pb(II). While the optimal pH was 4.0, and equilibrium time was 8 h. The adsorption capacity of Fe@BC for Pb(II) was 22.535 mg/g in mixed systems. Interestingly, the adsorption of Fe@BC for Pb(II) and Ni(II) exhibited a decreasing trend. In contrast, its adsorption for Cu(II) increased with the rising temperature. The fitting of theoretical models showed that the adsorption of Fe@BC for them followed quasi-second kinetic model, and such an adsorption was a spontaneous process. Additionally, the adsorption of Fe@BC for Pb(II) fitted well with Freundlich isotherm model. Conversely, its adsorption for Cu(II) and Ni(II) obeyed Langmuir–Freundlich isotherm model. Mechanisms of Fe@BC for metal ions mainly enclosed ion exchange, surface physic-sorption, pore adsorption, groups’ adsorption, and bonding effect. Regeneration of Fe@BC for Pb(II) showed that it can be cycled four times using HCl as a desorbent. Especially in the simulated wastewater, Fe@BC exhibited remarkable adsorption for metal ions and organic matters, demonstrating that it was a promising adsorbent for removing Pb(II) from wastewater.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The massive emissions of industrial wastes have led to severe pollution from heavy metal ions (HMIs). These HMIs will accumulate in food chains and generate serious threat to human health1,2. Typically, lead (Pb), copper (Cu), and nickel (Ni) are toxic heavy metal contaminants that are extremely prone to cause serious damage to human organs. For example, Pb is able to cause kidney, gastrointestinal and cardiovascular problems in human body3. While, Cu can damage human liver4. Similarly, excessive Ni will lead to a wide range of chronic and acute illnesses and damage the lungs and kidneys5,6. Clearly, if these toxic metals are discharged freely, they will cause serious pollution of HMIs in soil and water resources. In addition, Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) are the main compositions of electroplating effluent, mining and spent new-energy rechargeable battery7,8,9. Hence, developing effective techniques to remove or delete Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) from water medium has become a hot topic.

Currently, various effective methods are developed to remove these HMIs from water, they mainly contained ion exchange, chemical precipitation, bioremediation10, adsorption, and so on. Among which, adsorption revealed such advantages as high efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and the absence of secondary pollution. Therefore, adsorption and adsorbents become vital importance. Among these adsorbents, biochar (BC) adsorbents attract much interest due to their advantages such as rich polar functional groups, porous structure and low cost11. Presently, many authors conducted such investigations and gained great achievements. For example, Zhang et al.,12 used KOH activation of sludge to prepare biochar and used it to remove Pb(II) from water, it was reported that the amount of activated BC for Pb(II) could reach up to 57.48 mg/g. In addition, Zhang et al.,13 made magnetic chitosan/sludge BC to adsorb Cu(II) and found that the maximum adsorption capacity of Cu(II) was 55.16 mg/g. As a substitute, Zheng et al.,14 used chitosan-EDTA modified magnetic BC (E-CMBC) to remove HMIs from single Cu or Ni system, it was found that the maximum quantity of Cu and Ni was 48.36 mg/g and 41.17 mg/g, respectively. Obviously, biochar adsorption for HMIs can obtain good adsorption efficiency. However, the current study mainly focused on the removal of HMIs from mono-metal ions solution. Researches on the removal of HMIs from mixed systems were done little. Especially, these adsorbing materials are less environmentally friendly. Thus the current study is unsatisfactory. Developing green, low-cost and environmentally friendly adsorbing materials is highly needed.

It is well accepted that agricultural wastes are cheap adsorbing materials, they can be applied to prepare biochar adsorbents and used in the field of wastewater treatment. China is a major producer of peanuts and faces the tricky problems of waste peanut shells (PSHs). These agricultural waste PSHs are good biochar materials, they can be used to delete pollutants from water. It was reported that the recycling of PSHs can effectively decrease the emission of carbon dioxide15. While, PSHs used as biomass adsorbents exhibit adsorption capabilities for HMIs16. Moreover, using PSHs as adsorbents can achieve the goal of “waste to cure waste” and environmental friendliness. However, the raw PSHs adsorbents have lower adsorption capability for HMIs. Thus, the modification of PSHs adsorbents is an effective technique to increase their adsorption performances for HMIs. For example, Li et al.,17 prepared a Fe-modified biochar (HFO-BC) by impregnating hydrous ferric oxide (HFO). It was reported that the maximal sorption capacities of 29.9 mg/g for Cd(II) and 34.1 mg/g for Cu(II). In addition, Gupta et al.,18 prepared citric acid-modified peanut shell biochar (CA-GNH) and used it to adsorb Cu(II); it was found that its maximum adsorption capacity was 2.18 times higher than that of unmodified BC. Differing from these ordinary peanuts, it was reported that black peanuts (BP) had high sorption quantity for HMIs19. Hence, it is necessary to make deeper exploration using waste BP as biochar materials. Therefore the objective of this study is to produce a modified BC adsorbent using waste BP as a starting material and explores its adsorption for HMIs from multiple heavy metal systems and simulated industrial wastewater.

Considering that industrial wastewater is a complicated mixture of HMIs and organic matter. Thus competition will produce among them. However, the current researches mostly focus on the single or binary heavy metal systems. Little work is done to explore the removal of HMIs from mixed HMIs solutions, and HMIs/organic matter systems. Consequently, the current researches are insufficient. Due to this reason, we place our research on the removal of HMIs from multiple mixed systems. To further explore the adsorption selectivity of modified black PSHs for HMIs in multi-component systems and increase its adsorption for HMIs, herein, a novel Fe-modified black peanut shell biochar (Fe@BC) was fabricated, in which FeCl3 was used as a magnetic modifier to modify black PSHs. The role of FeCl3 as a Fe-based modifier is to advance its magnetism and adsorption capacity for HMIs. The Fe@BC was pyrolyzed at the temperature of 450, 550, 650 and 750 °C and its adsorption for HMIs in Pb(II)&Cu(II)&Ni(II) mixed solutions was evaluated. The adsorption process was scrutinized through kinetics and thermodynamics analyses. The adsorption mechanism of metal ions in mixed systems was also evaluated. The novelty of this job is: (1) A novel Fe-modified biochar (Fe@BC) was fabricated thru magnetic Fe-based modifier, in which FeCl3 was used to modify black peanut shell biochar. (2) As a representative metal ions from electroplating effluent, mining and spent new-energy rechargeable battery, its sorption for Pb(II) in multi-component Pb(II), Cu(II), Ni(II) mixed solution systems was explored. (3) The adsorption mechanism was scrutinized through kinetics and thermodynamics analyses. (4) Toward examine its application in industrial process, Fe@BC was used to remove HMIs from simulated industrial wastewater.

Material and methods

Material and chemicals

Black peanuts (BPs) were purchased from Sixian of Anhui province (Anhui, China), Both FeCl3·6H2O and NaOH were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). HNO3 was purchased from Yantai Shuang-Shuang Chemical Co. (Shandong, China). All reagents were AR grade.

Preparation of Fe@BC

Figure 1 is the flow chart for the preparation of Fe@BC. The preparation steps can be briefly described as follows.

First, black PSHs were washed repeatedly with deionized water to remove the sludge from their surfaces and then were dried to constant weight at 125 °C. Followed, the dried black PSHs were pulverized and soaked in deionized water for 24 h to remove the suspended matter and dried to constant weight. The obtained black PSHs powder was bagged for next using. Second, the Fe-modified PSHs (Fe@PSHs) were obtained by adding the washed black PSHs powder (ca.5 g) in FeCl3 solution (0.012 mol/L), sonicated for 2 h, and then dried to constant weight. Third, the Fe@PSHs were pyrolyzed at 450, 550, 650, and 750 °C for 3 h in a muffle furnace under air, respectively. Finally, the obtained Fe@BC underwent a thorough washing with deionized water and was subsequently dried to constant weight at 125 °C. For comparison, the unmodified peanut shell biochar (labeled as BC) was prepared under the same conditions.

Characterizations

The means for characterizing Fe@BC and BC included elemental analyzer (varioEL cube V4.0.2, German), scanning electron microscope (SEM, SU8010, Japan), energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS, SU8010, Japan), X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF, DY690, Netherlands), X-ray diffractometer (XRD, SmartLab SE, Nihon Rikaku Co.), fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR, Nicolet iS 50 + Contiuum, USA), thermogravimetric (TG, Q-500, USA), surface area analyzer (BET, ASAP 2460 3.01, USA), Dual Beam UV Spectrophotometer (UV, TU9001, China), atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS, AA900, USA), respectively.

Batch adsorption experiments

For the adsorption kinetics, the adsorption time was set as 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h. For the sorption thermodynamics, the temperature was changed from 25, 35, 45, to 55 °C. For the adsorption isotherms, the C0 of the ternary mixed metal ion solutions was set as 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 mg/L, respectively. All experiments were conducted thrice and the average values of three times testing was taken as the final results. The testing error was limited within 5%.

Desorption-adsorption studies were carried out to investigate the regeneration cycle times of Fe@BC. First, Fe@BC was adsorbed in mixed Pb(II)&Cu(II)&Ni(II) solutions (100 mg/L) for 24 h. Subsequently, the adsorbed Fe@BC was filtered and then immersed in hydrochloric acid (HCl) or sulfuric acid (H2SO4) solution (1 mol/L) for 2 h to conduct the desorption experiments, and then it was washed repeatedly with deionized water after the desorption was completed. Thus, the residual HCl or H2SO4 on the adsorbent can be removed. The sample was then dried and performed the next cycle, in which the desorption-adsorption experiments were repeated four times.

The adsorption capacity (Qe) of Fe@BC and BC for HMIs can be got from Eq. (1):

where C0 and Ce (mg/L) were the concentrations of initial and equilibrium state, respectively. V (mL) was the volume of mixed metal solutions, M (g) was the weight of Fe@BC or BC.

Adsorption of Fe@BC for HMIs from simulated industrial wastewater

As well known, industrial wastewater contains various HMIs and organic matter20. For example, electroplating industrial wastewater contains such HMIs as Pb, Cu, Ni, Cr, Cd, Zn and other substances21. Given the above contents of industrial wastewater simulants, the mixed metal ions solution (the total concentration of HMIs was set as 20 mg/L) containing Pb(II), Cu(II), Ni(II), Cr(III), and Co(II) was prepared. For comparison, it will be with and without citric acid and methylene blue. The reagents chosen for the experiments of simulated industrial wastewater were Pb(NO3)2, Cu(NO3)2, Ni(NO3)2, CrCl3, CoCl2, citric acid and methylene blue, in which citric acid and methylene blue were used as the organic additives. Referring to the literature22, the concentration ratios of each metal salt, citric acid, and methylene blue were set as 1:0:0, 1:1:1, and 1:2:2, respectively.

Model equations

Currently, it is well accepted that theoretical equations are very useful tool to examine the correctness of experimental data. As the theoretical equation was obtained from a specific system, thus it is hard to elucidate the experimental phenomena observed from other different systems. Hence, the fitting of tested data with theoretical equations only gives an approximate explanation. Such a description usually is inaccurate to various systems. To further verify the precision of tested data, multiple models are used to examine the identical tested data.

The theoretical equations used in this study are shown in Table 1.

Results and discussion

Determination of calcination temperature

To select proper calcination temperature, Fe@BC and BC were pyrolyzed within the range of 450–750 °C. Figure 2 showed the adsorption capacity of Fe@BC and BC pyrolyzed at 750 °C for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II). Clearly, upward trends are observed. Such trends suggested that higher temperature is more conducive to the adsorption of metal ions on modified BC19. Therefore, the calcination temperature of biochar in this case was established at 750 °C as the optimal condition. Additionally, by comparison of their Qe data, it was found that Fe@BC and BC had the best adsorption capacities for Pb(II), followed by Cu and Ni, i.e., their adsorption affinities for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) followed such a sequence as: Pb(II) > Cu(II) > Ni(II).

Elemental analysis

To determine the element contents (C, H, O, and N) in Fe@BC and BC, elemental analysis was made. Table 2 presents the elemental analysis of biochar at various calcination temperatures.

As shown in Table 2, element C was the major part in Fe@BC and BC. While, C content in both Fe@BC and BC increased with the elevated pyrolysis temperature. Conversely, both H and O contents decreased with the elevated pyrolysis temperature. Typically, at 750 °C, the C content peaked at 83.080% for BC and 78.370% for Fe@BC, in this case, the O content was 15.015% and 19.427%, and the H content was 1.085% and 1.483%, respectively. This might be due to the gradual loss of H and O containing functional groups as a result of pyrolysis at high temperatures35. While, at 750 °C, the atomic ratios of H/C, O/C, and (O + N)/C in BC decreased from 0.026 to 0.013, 0.370 to 0.181, and 0.380 to 0.191, respectively. Whereas those in Fe@BC decreased from 1.03 to 0.72, 0.304 to 0.248, and 0.318 to 0.257. This trend suggests that an increase in pyrolysis temperature will enhance the aromaticity, hydrophobicity, and polarity of both Fe@BC and BC, which will be more favorable for the removal of HMIs36.

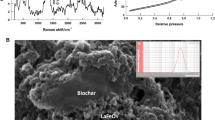

SEM images of Fe@BC and BC

To detect the changes of surface of Fe@BC and BC, SEM observation was performed and is presented in Fig. 3a–d.

In Fig. 3a,b, plenty of pore structures were found on the surfaces of Fe@BC and BC. By comparison with that of BC, the surface of Fe@BC became rougher. Much more particles and a larger pore structure are found, indicating that the modification of Fe can effectively change the surface structure of biochar. In Fig. 3c,d, more particles were produced on the surface of Fe@BC and BC; this indicated HMIs have successfully been adsorbed on biochar surface, achieving the transformation of HMIs from the solution to the sorbent37.

Qualitative analysis of Fe@BC and BC

To determine the changes in the constituents of Fe@BC and BC before and after adsorbed by HMIs, qualitative analysis was performed and is presented in Fig. 4.

As showed in Fig. 4a–d, the main constituents of original BC were C and O. After modification with FeCl3, Fe@BC primarily comprised C, O, and Fe. After adsorbed in a ternary solution, C, O, Pb, Cu, and Ni were found on the surface of BC. Whereas, C, O, Fe, Pb, Cu, and Ni were detected on the surface of Fe@BC. By comparison of the weight percentage of C and O on the adsorbed Fe@BC with those on the original Fe@BC, it can be seen that the weight percentage of C increased slightly (around 2% rise). In contrast, and the weight percentage of O reduced obviously (close 8% reduction). This finding implied the sorption of HMIs on the surfaces of Fe@BC and BC was successful completion.

XRF analysis

To determine the ingredients of Fe@BC and BC, XRF analysis was carried out and the relevant data are presented in Table 3.

As displayed in Table 3, the percentage of Ca content in the original BC was 91.133%. But, the percentage of Ca content decreased to 78.731% after modification with FeCl3. Accordingly, the percentage of Fe content increased to 15.904%. This finding implies that the loading of Fe had successfully introduced onto the surface of BC.

XRD pattern

To detect the changes in the peaks of modified BC and original BC, the observation of XRD patterns Fe@BC and BC was carried out. Figure 5 illustrates the XRD patterns of Fe@BC and BC. According to the PDF card (#05-0586) diffraction peaks of BC can be attributed to CaCO3 at 2θ = 23.02°, 29.37°, 35.90°, 39.42°, 43.11°, 47.42°, and 48.47°, corresponding to the crystal planes (012), (104), (110), (113), (202), (018), and (116), respectively38,39.

Compared with BC, the XRD pattern of Fe@BC didn’t reveal any new peaks except that there was a diffuse peak at 2θ = 24.13°, indicating that the Fe@BC was an amorphous carbon structure. Significantly, the diffraction peaks within the 35–50° range were notably diminished or even absent. This suggests that the impurities on the modified BC were effectively eliminated or that the impact of inorganic impurities on the adsorption efficiency was reduced. This finding further implied that Fe@BC played a pivotal role in augmenting the adsorption capability.

FT-IR spectra

To determine the position of functional groups on Fe@BC and BC, FT-IR spectra of Fe@BC and BC were detected and the relevant information are shown in Fig. 6.

From Fig. 6, the FT-IR spectra of Fe@BC and BC exhibited similar characteristics, indicating that the introduction of Fe3+ had minimal impact on the functional groups. The peak observed at 3404 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching vibration of –OH groups from both Fe@BC and BC40. The peak (~ 1616 cm−1) could be attributed to the stretching vibration of C=O bonds of the nonionic carboxyl groups (–COOH), which might be linked to carboxylic acids and/or their ester groups41. The peak (~ 1384 cm−1) was nominated to the vibration of nitrogen oxides in conjugated system, and the band at 1127 cm−1 can be assigned to C–O bond. Additionally, the peaks at 876 and 610 cm−1 were the stretching of aromatic –C–H out-of-plane42,43. Upon the adsorption by Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II), the peak positions of Fe@BC and BC experienced shifts. Specifically, the peaks of –OH (at 3404 cm−1), C=O (~ 1612 cm−1), N–O (~ 1383 cm−1), C–O (~ 1127 cm−1), C–H (~ 874, and 615 cm−1) were changed to ~ 3405, ~ 1617, ~ 1386, ~ 1137, ~ 873, and ~ 605 cm−1, respectively. Moreover, the intensities of these peaks underwent significant changes, especially the N–O peaks (for Fe@BC, its peak intensity ratio was increased near 2.77 times after adsorbed by HMIs) and C=O peaks (for Fe@BC, its peak intensity ratio was increased around 3.08 times after adsorbed by HMIs), probably because the addition of Pb(NO3)2, Cu(NO3)2, and Ni(NO3)2 caused Fe@BC and BC to adsorb NO3−44. These observations indicate the involvement of functional groups in the adsorption of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II).

TGA analysis

To insight into the thermal stability and degeneration procedure of Fe@BC and BC, TGA analysis was done and the data are presented in Fig. 7a,b.

Undoubtedly, the pyrolysis process of PSHs and Fe@PSHs was mainly parted into three stages (Fig. 7a). The first (< 230 °C) was the drying of samples. At this step, the water within the samples was volatilized, and the loss of adsorbed water resulted in a reduction in the mass percentage (4.41% for PSHs and 2.02% for Fe@PSHs, individually). The second (230–375 °C) was the pyrolysis stage. With an increase in temperature, hemicellulose and cellulose within the biomass decomposed rapidly, and the declining rate of weight loss percentage of PSHs and Fe@PSHs increased rapidly to 59.79 and 62.17%, respectively42. The third (> 375 °C) was the carbonizing process. The pyrolysis rates of PSHs and Fe@PSHs decreased significantly and gradually leveled off because the thermal decomposition was completed. The slow decomposition of lignin within the samples eventually pyrolyzed into biochar and ash.

Differencing from the degeneration of PSHs and Fe@PSHs, the degradation of Fe@BC and BC revealed various trends. Similarly, evaporation of water at the initial 0–100 °C resulted in a 13.54% and 17.27% weight loss percentage for Fe@BC and BC, respectively (Fig. 7b). The significant difference in the ratio of water loss percentage in Fe@PSHs and biochar may be attributed to the higher water content in Fe@PSHs. During pyrolysis, a small portion of thermal energy supplied to the Fe@PSHs, which was used to remove the intrinsic moisture, and most of it was used to raise its temperature. Most moisture reduced the degradation rate, thus it will elapse the time and increase the pyrolysis temperature45. In the second phase, the weight loss rates of Fe@BC and BC were 20.28% and 8.42%, which was attributed to the decomposition of less volatile organic matter46. Fe@BC and BC lost 2.62% and 2.05% of their weight in the third stage, respectively. The probable cause was the decomposition of carbonates into ash and aromatic structures. Throughout the whole process, the weight loss percentage of Fe@BC (27.75%) was lower than BC (36.44%), illustrating the superior thermal stability of Fe@BC after the modification of FeCl31.

Zeta potential and grain size

To examine the charge of surface of Fe@BC and BC, Zeta potential and particle sizes were measured and are given in Table 4 and Fig. 8a–c.

Normally, Zeta potential is used to describe the stability of solution system, the larger the absolute value of Zeta potential, the bigger the inter-particle repulsion, and the more uniform the particle dispersion, the more stable the system47. From Table 4, the Zeta potential values of Fe@BC and BC were − 17.6 and − 14.6 mV, respectively. That is, the negative charge and electronegative surface of Fe@BC and BC would be favorable for the adsorption of metal cations48. Since the difference in their zeta potential values and particle sizes was not significant, suggesting that the number of surface active sites between them was closer, but the Qe values of Fe@BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) was higher than those of BC, indicating the significant role of functional groups on Fe@BC.

BET analysis

Generally, the adsorption capacity of biochar for HMIs is associated with its specific surface area (SSA) and pore structure49. Figure 9a illustrated that the adsorption–desorption curves of Fe@BC and BC. Noticeably, the curves of BC exhibited I-type isotherms, suggesting that BC was monolayer adsorption and microporous filling occurred during the adsorption process. In contrast, the adsorption–desorption curves of Fe@BC belonged to type I/IV (Fig. 9b), indicating that Fe@BC was a microporous and mesoporous material. At very low relative pressure (P/P0), the adsorption amount of Fe@BC rose, which was probably due to the presence of a large number of microporous structures on the surface of Fe@BC; at higher relative pressures, the presence of mesoporous structures on the surface of Fe@BC led to a rise in the amount of adsorption of Fe@BC, and hysteresis loops appeared. As indicated in Table 5, the SSA of BC and Fe@BC increased from 740.012 to 820.504 m2/g, and the total pore volume increased from 0.317 to 0.503 cm3/g after modification with FeCl3. Compared with BC, Fe@BC had a larger pore size and SSA, such a pore structure will provide Fe@BC with more active sites for the sorption of HMIs and increase its adsorption capacity for HMIs.

The pore size distribution of Fe@BC and BC is given in Fig. 10. Evidently, the pore size of BC was 1.715 nm, while the pore size of Fe@BC was 2.454 nm. That is to say, after the modification with Fe3+, the holes of Fe@BC became larger than the unmodified BC, which will provide further evidence that BC was predominantly microporous, whereas Fe@BC was mainly characterized by a mesoporous structure.

To explain the above-named trends, two dominating factors such as the stiffness of inorganic modifier and composition of biochar need to be considered. One is the related to the stiffness of inorganic modifier FeCl3, which will provide Fe@BC with stronger support than BC during the period of calcination, resulting in an increase in SSA and pore size. The other can be attributed to the change in the composition of biochar. As presented in Table 2, for Fe@BC@750 and BC@750, the content (wt.%) of elements C and N in Fe@BC@750 was lower than that of BC@750. Conversely, the content (wt.%) of elements H and O in Fe@BC@750 was larger than that of BC@750. Such a composition in Fe@BC@750 will make its holes easy to collapse during the period of calcination. As a results, its SSA and pore size will become larger.

Sorption of Pb(II), Cu(II), Ni(II)

Effect of initial pH

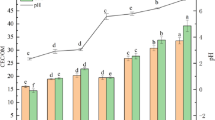

To investigate the impact of pH on the adsorption of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II) and Ni(II) in mixed metal ions solutions, pH versus the adsorption capacity of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) in mixed solution was explored, in which the initial pH was adjusted in the range of 2.0–5.0 by NaOH and HNO3. The related data are illustrated in Fig. 11.

From Fig. 11, the adsorption capacity of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) was all tend to increase and then decrease with the rise of pH values, and the adsorption capacity reached a maximum at pH = 4.0. The reason can be seen as follows. When pH = 2.0, the surface groups of biochar will bind with H+, which will reduce the negative charge of biochar surface, leading to a decrease in its sorption ability for heavy metal cations. Whereas, with the rising pH, the surface functional groups of biochar will lose their protons, thus it will rise the negative charge of biochar surface, accordingly the sorption amount of biochar for HMIs will be increased due to the effect of electrostatic attraction50. Typically, when pH = 4.0, the Qe of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) reached 19.854 and 21.804 mg/g, 8.324 and 19.416 mg/g, 1.350 and 2.212 mg/g, respectively. The adsorption order of biochar for them were ranked as Pb(II) > Cu(II) > Ni(II). Based on this result, the solution with pH 4.0 was selected as the optimal pH condition.

Influence of contact time

To insight into the influence of contact time on the Qe of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) in mixed metal ions solutions, the relationship of contact time against Qe was measured and is illustrated in Fig. 12.

Obviously, two sorption stages are found. In the first stage, the adsorption of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) increased with the elapsed time in very short time. In the second stage, such adsorptions became slow and reached the equilibrium as the time reached to 8 h. Therefore, the equilibrium time of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) was lower than 8 h. Several factors might be responsible for such trends. One is related to the combining force of functional groups on the surface of Fe@BC and BC to HMIs. Such forces is fast due to electrostatic effect. The second can be assigned to the effect of pore structure inside Fe@BC and BC. That is, inside hole will play a key role during the period of sorption of Fe@BC and BC for HMIs. Further, the amount of active sites on the surface of Fe@BC and BC will also generate some contributions to the sorption of Fe@BC and BC for HMIs. For example, the Qe of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) increased due to the high density of available active sites on the biochar adsorbents, but with the elapsed time, the amount of available active sites decreased, so the adsorption of metal ions gradually reached equilibrium state51. The adsorption of biochar for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) followed such an order as Pb(II) > Cu(II) > Ni(II).

Influence of solution concentration

Toward to detect the influence of initial concentration on the Qe of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) in mixed metal ions solutions, the relationship of initial concentration against Qe values of Fe@BC and BC was measured and is presented in Fig. 13.

From Fig. 13, their changing trends are different. For example, in the mixed metal ions solutions, the adsorption capacity of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Ni(II) increased with the elevated concentration. Conversely, the adsorption capacity of Cu(II) decreased with the increasing concentration. The adsorption of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) mostly reached the saturation state when the concentration of mixed metal ions solution was 100 mg/L. Therefore, the optimum condition was chosen as the solution concentration of 100 mg/L in the next experiment.

To explain the as-mentioned trends, the following dominating factors need to be considered. One is linked to the amount of metal ions in the mixed metal ions solution. If the amount of metal ions is considered, such trends are rational. It is well accepted that the higher the concentration of metal ions in solution, the larger the amount of metal ions in this solution. Accordingly, the amount of metal ions adsorbed by an adsorbent will be increased. Another factor will be associated to the competitive relation among metal ions. Due to the existence of completion among the metal ions, the sorption amount of metal ions on the adsorbent will be changed because of the difference in the adsorbing ability. Besides, the difference in the coordination number and the size of complex products will also be responsible for such trends.

Influence of solution temperature

Toward to evaluate the influence of solution temperature on the Qe of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) in mixed metal ions solution, the relationship of solution temperature versus Qe of Fe@BC and BC was determined and is given in Fig. 14.

From Fig. 14, it can be found that in the competitive adsorption of three HMIs, the adsorption capacity of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II) and Ni(II) decreased with the increasing solution temperature, implying that the adsorption of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), and Ni(II) was an exothermic process. That is to say, elevating solution temperature will be unhelpful for the adsorption of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II) and Ni(II). Conversely, the adsorption capacity of Fe@BC and BC for Cu(II) increased with an increase in solution temperature, suggesting that its adsorption was an endothermic process, i.e., elevating solution temperature will be conducive to the sorption of Fe@BC and BC for Cu(II).

Generally, adsorption of HMIs on an adsorbent in aqueous solution is an endothermic process. And increasing the temperature of solution will be conductive to the sorption of HMIs. However, in some case, adsorption of HMIs on an adsorbent in water might be an exothermic manner. Increasing the temperature of solution will prevent its adsorption. As mentioned-above, the sorption of Pb(II) and Ni(II) on Fe@BC and BC was a exothermic process. Adsorptive interaction among metal ions and functional groups might be responsible for such directions. As reported in an articles52,53, the decrease in the attraction force between Pb(II) and active adsorption sites will be one of the key factors. Moreover, the decrease in bonding energy will also make contributions to this downward trend as concluded in an article54.

Cyclic regeneration test

Given that the sorption capacity of Fe@BC for Ni(II) was relatively lower, so only the adsorption of Fe@BC Pb(II) and Cu(II) was evaluated during the cyclic regeneration test.

In Fig. 15, the adsorption capacity of Fe@BC for Pb(II) and Cu(II) decreased with an increase in cyclic times. However, the degree of desorption of Fe@BC for Pb(II) and Cu(II) under different desorption solutions was different. For example, after four times desorptions with HCl, the adsorption of Fe@BC for Pb(II) decreased from 22.535 to 8.723 mg/g, with a decrease of 61.290%; and the adsorption of Fe@BC for Cu(II) decreased from 20.119 to 8.440 mg/g, with a decrease of 58.050%. In contrast, after four times desorptions of H2SO4, the adsorption of Fe@BC for Pb(II) was reduced from 22.535 to 4.120 mg/g, with a decrease of 81.718%, and the adsorption of Fe@BC for Cu(II) was reduced from 20.119 to 16.110 mg/g, with a decrease of 19.976%. Overall, after four times cycles of desorption, the adsorption capacity of Fe@BC for Cu(II) was significantly larger than that of Pb(II), and the affinity for Cu(II) was increased. Regarding the degree of desorption, H2SO4 was an influenceive de-sorbent for the regeneration of Fe@BC.

The reason can be assigned to the solubility difference of Pb(II) and Cu(II) in HCl and H2SO4 solution. This is because Pb(II) is easy to combine with H2SO4 to generate the sediment of lead sulfate in solution. Conversely, lead chloride is a soluble substance in solution. Hence, the adsorbed Pb(II) on Fe@BC is easy to be desorbed by HCl. Similarly, Cu(II) is easy to unite with H2SO4 to produce the copper sulfate. While copper sulfate is a soluble substance in solution. In the same way, copper chloride is also a soluble substance in solution. Due to the larger discrepancy in the solubility between copper sulfate and copper chloride, thus the adsorbed Cu(II) on Fe@BC is more easier to be desorbed by H2SO4.

Adsorption dynamic model

Toward explore the adsorption mechanism of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II), several dynamics models were utilized to fit the testing data so as to assess the accuracy of experimental values.

Quasi-first (QFDM) and quasi-second (QSDM) dynamic model

Figure 16 shows the fitting curves of QFDM and QSDM of Fe@BC and BC for the adsorption of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II). The model factors are summarized in Table 6, in which qcal (mg/g) is the calculated value and qexp (mg/g) is the experimental value.

Moreover, χ2 is a suitable factor to check the fitting degree of testing and theoretical data from various models. The χ2 values of QFDM and QSDM equations were also listed in Table 6.

As shown in Table 6, the R2 of QSDM for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on BC (R2 = 0.993, 0.978, 0.990, respectively), and the R2 of the QSDM for Pb(II), Cu(II) and Ni(II) on Fe@BC (R2 = 0.998, 0.990, 0.997, respectively) were closer to those of QFDM. However, the χ2 values of QFDM were all lower than those of QSDM. Thus, it is easily concluded that the sorption of Pb(II) and Cu(II) on Fe@BC and BC followed QFDM. These outcomes suggest that the adsorption of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC and BC was a physical process. That is, surface complexation will play a key role during the period of HMIs adsorption.

Other dynamics models

Apart from QFDM and QSDM, some other dynamics models are also applied to evaluate the correctness of HMIs adsorption on an adsorbents. To further inspect the accuracy of testing data with the fitting values of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC and BC, IPDM, EDM, BDM, and DCDM were applied to match the experimental data. The fitting curves are presented in Fig. 17. The model factors are listed in Table 6.

Form Table 6, it can be seen that the R2 of EDM, BDM, and DCDM for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC and BC were all greater than 0.9, so these models were applicable for describing the adsorption process. Taking IPDM into consideration, since the R2 of IPDM for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC was lower than 0.9, suggesting that the sorption of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC didn’t fit IPDM, multiple steps will be the dominating process manner. On the contrary, the R2 of IPDM for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on BC was larger than 0.95, while, the intercept xi values were below 1.0. These findings demonstrated that the adsorption of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on BC obeyed IPDM, i.e., intra-particle diffusion inside the holes will be governed the adsorption process. Moreover, the R2 values of DCDM for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC were 0.999, 0.996, and 0.993; while the R2 values of DCDM for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on BC were 0.993, 0.993, and 0.989, respectively. But, the qe data obtained from DCDM were highly larger than the experimental values, demonstrating that the sorption of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC didn’t followed chemisorption.

Adsorption isothermal model

Langmuir (LIM), Freundlich (FIM) and Langmuir–Freundlich (LFIM)

Figure 18a–c is the isotherm fitting curves of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II). The model factors are tabulated in Table 7.

From Table 7, for the adsorption of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC, the R2 values of LIM and FIM are all very lower, suggesting that they didn’t obey these models. But, they fitted better with LFIM as the R2 of LFIM was greater than or approach to 0.9, so the adsorption also fitted with LFIM. Taking Pb(II) as an example, the R2 of FIM of (0.898) Pb(II) on Fe@BC was greater than that of LFIM (0.894). Therefore, Pb(II) sorption on Fe@BC followed FIM. In contrast, the sorption of Cu(II) and Ni(II) on Fe@BC abided by LFIM.

Other adsorption isothermal models

To investigate the sorption process of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC and BC, these isotherm models such as HeIM, RPIM, KCIM, SIM, and HiIM were chosen to fit the testing data. The fitting curves are presented in Fig. 19 and relevant factors are listed in Table 7.

From Table 7, the R2 of HeIM, RPIM, KCIM, and SIM was greater than or converged to 0.9 for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC and BC. Thus, the sorption of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) on Fe@BC and BC followed those isothermal models.

Thermodynamic calculation

To compute the thermodynamic factors of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II), thermodynamic model was created. Given the adsorption capacity of Fe@BC and BC for Ni(II) was very lower, its calculated results were not included in the text. As typical examples, thermodynamic calculated data of Pb(II) and Cu(II) adsorptions on Fe@BC and BC are given in Fig. 20. The related parameters were calculated and are summarized in Table 8.

From Table 8, the ∆G of Pb(II) adsorption on Fe@BC and BC was less than 0. Meanwhile, the ∆S values were larger than 0, and ∆H values were negative (< 0). These information suggest that the adsorption of Pb(II) on Fe@BC and BC was spontaneous, entropic, and exothermic. Similarly, the ∆G of Cu(II) adsorption on Fe@BC and BC was less than 0, and the ∆S data were larger than 0. However, the ∆H of Cu(II) adsorption on Fe@BC and BC was positive (> 0), proving that its adsorption was a spontaneous, entropic, and heat-absorbing process. These results are consistent with the observations in Fig. 14.

The removal of HMIs from simulated industrial wastewater

To extend the application of Fe@BC in industrial process, the removal of HMIs from simulated industrial wastewater usiong Fe@BC and BC as adsorbents was performed. Figure 21 exhibited the adsorption of Fe@BC and BC for five different HMIs [i.e., Cu(II), Pb(II), Cr(III), Co(II) and Ni(II)], citric acid and methylene blue in simulated industrial wastewater.

In Fig. 21a–c, it described an obvious increase in the adsorption of Fe@BC and BC for Pb(II) and Cu(II). On the contrary, the adsorption of Fe@BC and BC for Ni(II), Cr(III), and Co(II) was weaker as the concentration of citric acid and methylene blue in the mixture was increased. Furthermore, under the specific condition in which the concentration ratio of HMIs to citric acid to methylene blue was maintained at 1:2:2, the sequence of HMIs sorption onto Fe@BC and BC followed such an order: Cu(II) > Pb(II) > Cr(III) > Co(II) > Ni(II).

Figure 21d,e portrayed the absorption of citric acid and methylene blue on Fe@BC and BC. When the concentration ratio of HMIs: citric acid: methylene blue was equal to 1:1:1, Fe@BC and BC exhibited similar adsorption capacity and could completely remove citric acid and methylene blue (Fig. 21d). However, when the concentration ratio was 1:2:2, the absorbance of Fe@BC at the adsorption equilibrium was lower than that of BC, which indicated that Fe@BC had a better adsorption for citric acid and methylene blue. According to the literature55, the adsorption process of organic pollutants by porous biochar includes both physical and chemical adsorption, inferring that Fe@BC had good affinity for citric acid and methylene blue, this was due to its larger SSA and pore structure. Additionally, by comparison of the test tubes, it was evident that the color intensity of three test tubes followed a gradient tendency from light to dark: III (sorption by Fe@BC), II (sorption by BC), and I (stock solution) (Fig. 21e). Therefore, Fe@BC had a better influence on the treatment of simulated wastewater.

Adsorption mechanism

Adsorption mechanism56,57 will be a useful tool to explore the adsorption process of an adsorbent for the removal of HMIs from water. Figure 22 illustrated the possible adsorption mechanisms of Fe@BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) in industrial wastewater, primarily encompassing cation exchange, surface physisorption, pore adsorption, groups adsorption, and bonding58, which will be discussed below.

As stated in an article59, HMIs can conduct ion exchange reactions with other cations such as (Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+) released from biochar. Both XRD and XRF analyses revealed the presence of Ca2+ in Fe@BC, while XRF and EDS images confirmed the occurrence of Fe3+ in Fe@BC. Ca2+ and Fe3+ can perform ion exchange reactions with Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) by cation exchange manner60. Thus, Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) can be removed from water through cation exchange.

The surface of Fe@BC exhibited numerous functional groups, including –OH, C=O, N–O, C–O, and C–H. FT-IR spectra proved that the shifts in the position of functional groups. As presented in Fig. 6, the peak intensity ratio of N–O and C=O had larger increase after adsorbed by HMIs. These changes prove the combination of functional groups with HMIs. Consequently, functional groups adsorption will be one of the adsorption mechanisms61. In addition, FT-IR indicated the presence of stretching vibrational peaks from aromatic C–H (Fig. 6). These aromatic structures could promote the binding with HMIs by providing more π-electron interaction62, so there will exist a cationic π-bonding mechanism.

The fitting of dynamic models evidenced that the sorption of Pb(II) and Cu(II) on Fe@BC followed QFDM and it was a physical process. Thus, surface complexation is one of the major mechanisms. Besides, the adsorption of Fe@BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) didn’t solely fit IPDM model and multiple steps will be the dominating process. Therefore, pore adsorption will be involved in this process. Furthermore, the matching of isotherm models disclosed that the adsorption of Fe@BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) didn’t obey LIM and FIM model, proposing that mono-layer Langmuir adsorption or chemical adsorption was not the chief mechanism.

A comparison of Qe with those reported in other references

To assess the potential application of Fe@BC in industry, the comparison of Qe of Fe@BC for HMIs in multi-component systems with those reported in other references was done and lists in Table 9. Clearly, Fe@BC exhibited better adsorption capability for Pb(II) and Cu(II), showing that Fe@BC is a promising adsorbent for the removal of metal ions from mixed HMIs and/or organic matter solutions.

Conclusion

A new Fe@BC adsorbent was obtained by using FeCl3 as a magnetic modifier. Its adsorption for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) in multi-component systems were inspected. The following results can be achieved:

-

(1)

The optimal removal conditions of Fe@BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) were pH 4.0, and time 8 h. Meanwhile, for Pb(II), HCl was an effective de-sorbent for the regeneration of Fe@BC.

-

(2)

Theoretical models indicated that the sorption of Fe@BC for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) were chemisorptive process. While, the adsorption of Fe@BC for Pb(II) was a spontaneous, entropy-increasing, and exothermic process. Whereas, its adsorption for Cu(II) was a spontaneous, entropy- increasing, and heat-absorbing process. Moreover, the sorption of Fe@BC for Pb(II) followed FIM model. Contrariwise, its adsorption for Cu(II) and Ni(II) abided by LFIM.

-

(3)

Mechanism insight suggested that the sorption of Fe@BC for HMIs possibly included cation exchange, surface physisorption, pore adsorption, groups adsorption, and bonding.

-

(4)

Fe@BC showed superiority in the removal of HMIs from simulated industrial wastewater, exhibiting promising application in the treatment of industrial wastewater.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current job are available upon reasonable request.

References

Shan, R., Shi, Y., Gu, J., Wang, Y. & Yuan, H. Single and competitive adsorption affinity of heavy metals toward peanut shell-derived biochar and its mechanisms in aqueous systems. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 28(5), 1375–1383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjche.2020.02.012 (2020).

Rajendran, S. et al. A critical review on various remediation approaches for heavy metal contaminants removal from contaminated soils. Chemosphere 287, 132369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132369 (2022).

Bombuwala, D. N., Fowler, R. E., Pittman, C. U. Jr., Mohan, D. & Mlsna, T. Lead (Pb2+) sorptive removal using chitosan-modified biochar: batch and fixed-bed studies. RSC Adv. 8(45), 25368–25377. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ra04600j (2018).

Guan, B.-B. et al. Highly selective and sensitive detection towards cationic Cu2+ and Fe3+ contaminants via an In-MOF based dual-responsive fluorescence probe. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 122, 108273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108273 (2020).

Borba, C. E., Guirardello, R., Silva, E. A., Veit, M. T. & Tavares, C. R. G. Removal of nickel(II) ions from aqueous solution by biosorption in a fixed bed column: Experimental and theoretical breakthrough curves. Biochem. Eng. J. 30(2), 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2006.04.001 (2006).

Priyantha, N. & Kotabewatta, P. A. Biosorption of heavy metal ions on peel of Artocarpus nobilis fruit: 1—Ni(II) sorption under static and dynamic conditions. Appl. Water Sci. 9(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-019-0911-2 (2019).

Shi, H. et al. The preparation of Fe3O4-MnO2-SiO2-NH2 for selective adsorption of Pb(II) in mixed solution of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II). Water Air Soil Pollut. 234, 381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-023-06353-1 (2023).

Al-Qahtani, K. M. et al. Efficiency of extremophilic microbial mats for removing Pb(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) ions from aqueous solutions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 53365–53378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14571-5 (2021).

Imran-Shaukat, M., Wahi, R. & Ngaini, Z. Bio-based activated carbon for Cu(II), Ni(II), and Pb(II) ions aqueous sequestration: Physiochemical characterization, isotherms, and kinetics. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-024-05856-6 (2024).

Singh, A. et al. Biological remediation technologies for dyes and heavy metals in wastewater treatment: New insight. Bioresour. Technol. 343, 126154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126154 (2022).

Xiao, J., Hu, R., Chen, G. & Xing, B. Facile synthesis of multifunctional bone biochar composites decorated with Fe/Mn oxide micro-nanoparticles: Physicochemical properties, heavy metals sorption behavior and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 399, 123067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123067 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Sludge-based biochar activation to enhance Pb(II) adsorption. Fuel 252, 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.04.096 (2019).

Zhang, M., Liu, Y., Yin, Z., Feng, D. & Lv, H. Preparation and adsorption properties of magnetic chitosan/sludge biochar composites for removal of Cu(2+) ions. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 20937. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46815-4 (2023).

Zheng, L. et al. Single and binary adsorption behaviour and mechanisms of Cd2+, Cu2+ and Ni2+ onto modified biochar in aqueous solutions. Processes 9(10), 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9101829 (2021).

Bai, S., Wang, T., Tian, Z., Cao, K. & Li, J. Facile preparation of porous biomass charcoal from peanut shell as adsorbent. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 15845. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72721-0 (2020).

Johnson, P. D., Watson, M. A., Brown, J. & Jefcoat, I. A. Peanut hull pellets as a single use sorbent for the capture of Cu(II) from wastewater. Waste Manag. 22(5), 471–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0956-053x(01)00036-8 (2002).

Li, Y. et al. Enhanced removal of heavy metals from water by hydrous ferric oxide-modified biochar. ACS Omega 5, 28702–28711 (2020).

Gupta, N. & Sen, R. Kinetic and equilibrium modelling of Cu(II) adsorption from aqueous solution by chemically modified Groundnut husk (Arachis hypogaea). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 5(5), 4274–4281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2017.07.048 (2017).

Duan, Q. et al. Ba-modified peanut shell biochar (PSB): Preparation and adsorption of Pb(II) from water. Water Sci. Technol. 88(7), 1795–1820. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2023.305 (2023).

Ajiboye, T. O., Oyewo, O. A. & Onwudiwe, D. C. Simultaneous removal of organics and heavy metals from industrial wastewater: A review. Chemosphere 262, 128379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128379 (2021).

Ramrakhiani, L., Ghosh, S. & Majumdar, S. Heavy metal recovery from electroplating effluent using adsorption by jute waste-derived biochar for soil amendment and plant micro-fertilizer. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 24(4), 1261–1284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-021-02243-4 (2022).

Kabra, K., Chaudhary, R. & Sawhney, R. L. Solar photocatalytic removal of Cu(II), Ni(II), Zn(II) and Pb(II): Speciation modeling of metal–citric acid complexes. J. Hazard. Mater. 155(3), 424–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.11.083 (2008).

Tang, L. et al. Adsorption of acetone and isopropanol on organic acid modified activated carbons. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 4(2), 2045–2051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2016.03.031 (2016).

Saha, B., Shil, G., Debnath, A. & Saha, B. Process optimization of victoria blue dye removal using polypyrrole-encapsulated zirconium oxide: Mechanistic pathway and economic assessment. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 101(11), 101407 (2024).

Gelaw, Y. B. et al. Adsorptive removal of cadmium(II) from wastewater using activated carbon synthesized from stem of Khat (Catha edulis). Heliyon 10, e40389 (2024).

Choque-Quispe, D. et al. Multimetal removal in aqueous medium using a potato starch/nopal mucilage copolymer: A study of adsorption kinetics and isotherms. Results Eng. 18, 101164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101164 (2023).

Li, C., Chen, D., Ding, J. & Shi, Z. A novel hetero-exopolysaccharide for the adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solutions: Isotherm, kinetic, and mechanism studies. J. Clean. Prod. 265, 121800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121800 (2020).

Chigbundu, E. C. & Adebowale, K. O. Equilibrium and fractal-like kinetic studies of the sorption of acid and basic dyes onto watermelon shell (Citrullus vulgaris). Cellulose. 24(11), 4701–4714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-017-1488-2 (2017).

Clark, I., Smith, J., Gomes, R. L. & Lester, E. Continuous synthesis of Zn2Al-CO3 layered double hydroxides for the adsorption of reactive dyes from water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7(3), 103175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.103175 (2019).

Jeppu, G. P. & Clement, T. P. A modified Langmuir-Freundlich isotherm model for simulating pH-dependent adsorption effects. J. Contam. Hydrol. 129, 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2011.12.001 (2012).

Xie, S., Wen, Z., Zhan, H. & Jin, M. An experimental study on the adsorption and desorption of Cu(II) in silty clay. Geofluids 2018(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3610921 (2018).

Fernandes, E. P. et al. Efficient adsorption of dyes by γ-alumina synthesized from aluminum wastes: Kinetics, isotherms, thermodynamics and toxicity assessment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9(5), 106198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2021.106198 (2021).

Tran, H. N. et al. Thermodynamic parameters of liquid–phase adsorption process calculated from different equilibrium constants related to adsorption isotherms: A comparison study. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9(6), 106674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2021.106674 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. Biochars and modified-biochars for toxic-metal ions sorption in various mixed solution systems: A review on kinetic and isotherm models. Desalin. Water Treat. 319, 100404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dwt.2024.100404 (2024).

Kong, L., Gao, Y., Zhou, Q., Zhao, X. & Sun, Z. Biochar accelerates PAHs biodegradation in petroleum-polluted soil by biostimulation strategy. J. Hazard. Mater. 343, 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.09.040 (2018).

Guo, J., Wen, X., Yang, J. & Fan, T. Removal of benzo(a)pyrene in polluted aqueous solution and soil using persulfate activated by corn straw biochar. J. Environ. Manag. 272, 111058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111058 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. MgO-laden biochar enhances the immobilization of Cd/Pb in aqueous solution and contaminated soil. Biochar. 3(2), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-020-00080-0 (2021).

Estrada-Flores, S. et al. Facile synthesis of novel calcium silicate hydratednylon 6/66 nanocomposites by solution mixing method. RSC Adv. 8, 41818 (2018).

Yang, X., Cao, M., Hong, W., Li, L. & Chen, X. Preparation and microwave dielectric properties of calcite (CaCO3) ceramics. Ceram. Int. 50, 36948–36954 (2024).

Yun, X. et al. Pb(II) adsorption by biochar from co-pyrolysis of corn stalks and alkali-fused fly ash. Biochar. 4(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-022-00189-4 (2022).

Sattar, M. S. et al. Comparative efficiency of peanut shell and peanut shell biochar for removal of arsenic from water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26(18), 18624–18635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05185-z (2019).

Kushwaha, R., Singh, R. S. & Mohan, D. Comparative study for sorption of arsenic on peanut shell biochar and modified peanut shell biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 375, 128831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2023.128831 (2023).

Shakya, A., Vithanage, M. & Agarwal, T. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on biochar properties and Cr(VI) adsorption from water with groundnut shell biochars: Mechanistic approach. Environ. Res. 215, 114243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.114243 (2022).

Ding, C. et al. Competitive sorption of Pb(II), Cu(II) and Ni(II) on carbonaceous nanofibers: A spectroscopic and modeling approach. J. Hazard. Mater. 313, 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.04.002 (2016).

Tripathi, M., Sahu, J. N. & Ganesan, P. Effect of process parameters on production of biochar from biomass waste through pyrolysis: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 55, 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.122 (2016).

Leng, L. J. et al. Characterization and application of bio-chars from liquefaction of microalgae, lignocellulosic biomass and sewage sludge. Fuel Process. Technol. 129, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2014.08.016 (2015).

Inyang, M. I. et al. A review of biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46(4), 406–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2015.1096880 (2015).

Ding, Z. et al. Sorption of lead and methylene blue onto hickory biochars from different pyrolysis temperatures: Importance of physicochemical properties. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 37, 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2016.03.035 (2016).

Lemraski, E. G. & Sharafinia, S. Kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamics studies of Pb2+ adsorption onto new activated carbon prepared from Persian mesquite grain. J. Mol. Liq. 219, 482–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2016.03.031 (2016).

Qiu, B. et al. Biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal: A review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 155, 105081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2021.105081 (2021).

Ibrahim, A. G. et al. Chitosan-g-maleic acid for effective removal of copper and nickel ions from their solutions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 121, 1287–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.107 (2019).

Liu, X., Lai, D. & Wang, Y. Performance of Pb(II) removal by an activated carbon supported nanoscale zero-valent iron composite at ultralow iron content. J. Hazard. Mater. 361, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.08.082 (2019).

Zhang, M. et al. High and fast adsorption of Cd(II) and Pb(II) ions from aqueous solutions by a waste biomass based hydrogel. Sci. Rep. 10, 3285. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60160-w (2020).

Ojembarrena, F. et al. Ni(II) and Pb(II) removal using bacterial cellulose membranes. Polymers 15, 3684. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15183684 (2023).

Wu, T., Yang, G., Cao, J., Xu, Z. & Jiang, X. Activation and adsorption mechanisms of methylene blue removal by porous biochar adsorbent derived from eggshell membrane. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 188, 330–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2022.08.042 (2022).

Bulin, C., Zheng, R. & Guo, T. Fabrication of ion imprinted chitosan-polyethylene glycol-polyvinyl alcohol hybrid membrane for selective recovery of Nd(III). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 282, 136845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136845 (2024).

Bulin, C., Guo, T., Zheng, R. & Xiong, Q. Interaction mechanism of phytic acid functionalized graphene oxide with ionic dyes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 330, 125369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2023.125369 (2024).

Liu, S., Feng, Y. & Li, H. Mechanism of deep-sea microbial-mediated synergistic synthesis of ferromanganese oxidation products process for heavy metal ion adsorption. JOM 75(12), 5405–5419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-023-06130-9 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. Enhanced heavy metals sorption by modified biochars derived from pig manure. Sci. Total Environ. 786, 147595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147595 (2021).

Zeng, Q. et al. Oxalic acid modified copper tailings as an efficient adsorbent with super high capacities for the removal of Pb(2). Chemosphere 263, 127833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127833 (2021).

Zhuang, S., Mei, Y. & Wang, J. Adsorption performance and mechanisms of Co2+ onto carboxyl-functionalized carbon nanotubes. J. Clean. Prod. 430, 139709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139709 (2023).

Zhou, N. et al. Effect of pyrolysis condition on the adsorption mechanism of heavy metals on tobacco stem biochar in competitive mode. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26(26), 26947–26962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05917-1 (2019).

Lee, H. S. & Shin, H. S. Competitive adsorption of heavy metals onto modified biochars: Comparison of biochar properties and modification methods. J. Environ. Manag. 299, 113651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113651 (2021).

Guan, J. et al. Adsorption of heavy metals by Lycium barbarum branch-based adsorbents: Raw, fungal modification, and biochar. Water Sci. Technol. 85(7), 2145–2160. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2022.067 (2022).

Wang, S., Li, X. & Zhu, Y. Comparison of the adsorption capacity and mechanisms of mixed heavy metals in wastewater by sheep manure biochar and Robinia pseudoacacia biochar. Water Sci. Technol. 87(12), 3083–3094. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2023.180 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the University Natural Science Research Projects of Anhui Province (No. 2023AH052200) and the State Key Laboratory of Materials-Oriented Chemical Engineering (KL21-04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author statement Qianqian Duan: Methodology, Material preparation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing-original draft. Jingyi Chen: Project administration, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. Junsheng Liu: Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. Shuo Zhang: Investigation, Formal analysis. Junfei Zhang: Investigation, Data curation. Shitao Lin: Investigation, Data curation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Duan, Q., Liu, J. et al. Adsorption of Fe-modified peanut shell biochar for Pb(II) in mixed Pb(II), Cu(II), Ni(II) solutions. Sci Rep 15, 13558 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97042-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97042-y