Abstract

In the past 10 years, anesthesiologists have been concentrating on opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) and utilizing locoregional anesthesia/analgesia to manage pain during open and laparoscopic surgeries. The goal is to reduce the negative effects of using opioids during and after surgery. This study aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of OFA protocol with low doses of magnesium sulfate, Clonidine, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) employing transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block and rectus sheath block (RSB) for intraoperative and postoperative pain control in laparoscopic abdominal surgery. We conducted a single-center unblinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) to compare the OFA protocol with bilateral TAP and RS block versus the conventional analgesic plan with opioids. We included all consecutive patients older than 18 who planned for laparoscopic scheduled abdominal surgery and underwent general anesthesia. We found a statistically significant lower numeric rating scale (NRS)score at each time point in the OFA group (p < 0.001). A significant statistical difference was also found in the mobilization recovery time, which occurred at 36.00 [18.00, 48.00] hours in the OFA group versus 48.00 [24.00, 72.00] hours in the control one (p < 0.001). The length of stay (LOS) was also in favor of the OFA group 4.00 [2.00, 6.00] days versus 6.00 [4.00, 9.00] days in the control one (p < 0.001). Concerning side effects, there was a reduced/null onset in the OFA group compared with the control. No ICU admissions were recorded in the first 24 h after the end of surgery. This study showed that the preoperative implementation of locoregional anesthesia techniques with our OFA protocols guarantees the adequacy of intraoperative antinociception, while low dose magnesium sulfate and clonidine ensure hemodynamic stability comparable to opioids during surgery. OFA eliminates the side effects of opioids and decreases patients’ length of stay and early mobilization without requiring additional drugs.

Trial registration ISRCTN15228105. Retrospectively registered 02/12/2023.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Under general anesthesia, nociception occurs without pain. This means that nociception and pain are different phenomena. In this context, intraoperative analgesia controls the autonomous nervous system response to nociception1. After surgery, patients often experience acute postoperative pain (20–40%) caused by direct damage to peripheral nerve fibers and alterations in neuromodulation1. In addition, a considerable percentage (20–65%) also experience chronic postoperative pain (CPOP), which is closely related to perceived long-term disability after recovery from surgery and significantly affects the individual’s quality of life2.

Hence, in recent years, anesthesiologists have focused on opioid-sparing anesthesia, multimodal anesthesia that combines different drugs and techniques. Locoregional anesthesia/analgesia ensures a perfect blockage of nociceptive afferents, while drugs (i.e., lidocaine, ketamine, magnesium sulfate, dexamethasone, NSAIDs, alpha- 2-agonists) that interfere with the sympathetic system preserve the hemodynamic response to the surgical stimulus3. The goal is to reduce the negative effects of opioids and episodes of acute postoperative pain. The most frequently reported side effects of opioids are postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) and constipation4. In the high-risk class of patients, PONV has been reported in 80% of cases4,5. PONV can have a negative impact on well-being and patient satisfaction, increase morbidity (dehydration, wound dehiscence, pain, and immobility), and lead to longer hospital stays and higher hospital cost5. Additionally, a hypothesis has been posited that the use of opioids may increase the risk of metastasis and cancer recurrence in cancer surgery6.

Evidence of the role of magnesium in analgesic adjuvants against a range of acute and chronic pain has accumulated over the decades. Magnesium is a noncompetitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor antagonist with antinociceptive effects, central sensitization, and inhibitor of catecholamine release7,8.

Recent studies have shown that during general anesthesia, the intravenous administration of magnesium sulfate significantly reduces the use of anesthetics, analgesics, and opioids and extubation time, improves hemodynamic stability, and attenuates postoperative pain intensity without increasing the risk of adverse events in various surgeries9,10, and, if associated with IV infusion of local anesthetics, ensures the prolonged duration of the block11,12.

Ketamine possesses both analgesic and antihyperalgesic properties, reducing postoperative pain, analgesic needs, and intraoperative blood pressure variability12.

Because a significant feature of opioids is to maintain intraoperative hemodynamic stability, OFA should minimize sympathetic response. α2- adrenergic agonists (clonidine and dexmedetomidine) may provide analgesia, antihyperalgesia, sedation/hypnosis, anxiolysis, anti-emesis, and sympatholysis12. Alpha- 2 adrenergic agonists should be considered hemodynamic stabilizers.

Intravenous lidocaine carries various beneficial effects related to both anti-nociceptive and antihyperalgesic properties13. Lidocaine also acts as an anti-inflammatory drug. Combined mechanisms of action translate into clinical benefits: analgesia with morphine-sparing effect, secondary reduction of PONV, earlier resumption of transit, faster rehabilitation, and reduced length of stay12,13,14.

The international scientific community has investigated the use of locoregional anesthesia/analgesia in the pain management of different surgical procedures and standardized protocol that recommends its use in all open and laparoscopic surgical abdominal procedures15. Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block, ultrasound-guided (USG) administration of local anesthetic in the interfascial space between the transversus abdominis muscle and the internal oblique abdominal muscle, ensures the block of the ventral rami of spinal nerves T6-T11 and wall anesthesia16,17,18.

Similarly, the rectus sheath block (RSB), USG administration of local anesthetics in the interfascial plane between the rectus muscle and the posterior rectus sheath, was performed in surgical procedures with a midline approach on the abdominal wall19.

Locoregional anesthesia, alone or in combination with general anesthesia, reduces endocrine response to surgical stress15. This is due to sympathetic blockade combined with afferent blockade of central chordal fibers that modulate the pituitary-adrenocortical system. However, limited data on the stress response during infiltration anesthesia or nerve block associated with OFA are available15.

This study aims to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of the OFA protocol with low doses of magnesium sulfate and NSAIDs in association with TAP and RS block to ensure adequate intraoperative anesthesia and satisfactory postoperative pain control.

Methods

We conducted a single center unblinded randomized controlled trial to compare the OFA protocol with bilateral TAP block and RSB versus the conventional analgesic plan with opioids. The study (register n° 118 AOR/29 - 04- 2019) was approved by the Palermo2 Ethics Committee (n°16/13 - 06- 2019). The trial was retrospectively registered on 02/12/2023 (ISRCTN15228105). All research methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

The study was reported according to the CONSORT checklist (CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Statement).

Inclusion criteria

We included all consecutive patients older than 18 who planned for laparoscopic scheduled abdominal surgery and underwent general anesthesia at Villa Sofia Hospital of AOOR Villa Sofia-Cervello in Palermo from 1 October 2020 to 31 December 2022. The patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to control or intervention group. The allocation sequence used computer-generated random numbers in a block of fours and allocation concealment20.

Exclusion criteria

Age below 18 years old; pregnant women; confirmed diagnosis of hypermagnesemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, hyperkalemia; acidosis states; acute or chronic kidney disease; hypothyroidism; hypoadrenocorticism; neuromuscular disorders; bradycardia; bradyarrhythmia; AtrioVentricular block; pacemaker; heart failure associated with hypotension and reduced cardiac function; shock.

Each patient underwent preoperative evaluation to evaluate anesthesiologist risk according to the ASA and signed the informed consent to be involved in the study at least 24 h before the scheduled surgery.

After admission to the operating room, all patients were monitored with continuous monitoring of heart rate (HR), noninvasive blood pressure (NIBP), pulse oximetry (SpO2), bispectral index (BIS), and Train of Four (TOF). If necessary, other monitoring techniques (i.e., Invasive Blood Pressure, ClearSight) were adopted according to surgical specialties.

Intervention groups

Preoperative management

Based on ideal body weight (IBW), patients were premedicated with IV 75 mcg clonidine and 0.05 mg/kg midazolam in bolus. Thus, locoregional anesthesia of the abdominal wall was performed by expert operators: first, single-shot ultrasound-guided (USG) bilateral TAP block with the administration of 20–25 ml of ropivacaine (0.3%) for each side, in an overall volume of 40–50 ml, according to patient body mass index (BMI); finally, single-shot USG-bilateral RSB with the administration of 10 ml of ropivacaine (0.3%), for each side, in an overall volume of 20 ml, according to patient BMI. After the execution, the efficacy and extension of the blocks were tested with a prick test after 15 min. Five minutes before induction, a bolus of 30 mg/kg magnesium sulfate in 100 ml of 0.9% NaCl solution was administered; after that, an intravenous infusion of 8 mg/kg/h magnesium sulfate 5% was started.

Intraoperative management

A continuous intravenous infusion of 90 mg ketorolac (2 ml/h) in a solution of 48 ml NaCl 0.9% was administered 10 min after the surgical incision.

The continuous intravenous infusion of magnesium sulfate was stopped 5 min before the end of the surgery, and an IV 1 g acetaminophen bolus was administered 15 min before the end of surgery.

Postoperative management

Rescue analgesia: 1 g of acetaminophen IV a bolus was administered if NRS > 3 in the 24 h from the end of the surgery.

Dropout criteria

An opioid-based rescue therapy (IV 3 mcg/kg of fentanyl, according to clinical conditions of patients) would have been administered if the following intraoperative criteria after surgical stimulus were present.

-

1.

Blood pressure and heart rate of more than 20% of related presurgical incision values, not correctable by increasing halogenated inspiratory fraction within the therapeutic range.

-

2.

BIS < 40 with clinical signs of pain (i.e., tearing, sweating) not removed by increasing the halogenated inspiratory fraction within the therapeutic range.

-

3.

Insufficient regional anesthesia documented also by pinprick preoperatively.

In these conditions, the OFA protocol would have been considered unsafe to ensure an adequate analgesic plan, and opioids would have been administered. Intraoperative administration of an IV continuous infusion of remifentanil was considered according to the patient’s clinical conditions and rescue therapy clinical response.

Control group

Preoperative management

Midazolam 0.05 mg/kg IV.

Intraoperative management:

Target-controlled infusion (TCI) IV (3 to 5 ng/ml corresponding to 0.1 to 0.25 µg·kg − 1·min − 1 of remifentanil. IV bolus 1 g acetaminophen plus IV ondansetron (4 mg) was administered 30 min before the end of surgery.

Postoperative management

Continuous infusion (2 ml/h) with an elastomeric pump of 90 mg ketorolac and 0.1 mg/kg/h morphine was administered in the 24 h postoperative period.

Rescue analgesia: 1 g of acetaminophen IV a bolus was administered if NRS > 3 in the 24 from the end of the surgery.

General anesthesia was induced by administering IV 2 mg/kg propofol 1% in 60 s and IV 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium bromide in 15 s. Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane 1–3%, according to the patients’ clinical conditions and response21.

Administering rocuronium bromide 10 mg in bolus according to TOF ≥ 2.i.v ensured muscle paralysis. Figure 1.

Antibiotic prophylaxis according to local guidelines was carried out in both groups.

All patients were admitted to the recovery room and monitored for heart rate, noninvasive blood pressure, and pulse oximetry.

The patients were discharged from the PACU when their Aldrete score was higher than 922.

Pain was assessed by the NRS scale in the postoperative period: at the end of surgery (T0) and at 6 (T1)− 12 (T2)− 18 (T3)− 24 (T4) hours.

Moreover, we recorded adverse effects such as hypoxemia, defined as a SpO2 level of less than 95% with a need for oxygen supplementation; postoperative ileus, defined as an absence of flatus or stools; postoperative nausea and vomiting with the need for rescue antiemetic medication, unplanned intensive care unit (ICU) admission, mobilization recovery time, and in-hospital length of stay3.

Sample size

We based our sample size calculation on the postoperative NRS score from the literature1. The anticipated percentage of NRS scores > 3 postoperatively was 40%. We considered a 50% reduction in the OFA group to be clinically relevant. With a type 1 error of 0.01 and a power of 90%, a sample size calculation determined that 164 patients per group were needed in the study. We aimed to recruit an additional 10% of patients for drop-out or loss to follow-up. The sample size was calculated using R software (version 2.6 - 1).

Primary outcome

Primary outcomes were postoperative pain control evaluated with NRS at each time point and episodes of postoperative pain (defined as any episode with a numeric rating scale greater than or equal to 3) within 24 h after extubation.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome was a composite of mobilization recovery time and in-hospital length of stay with postoperative adverse events within the first 24 h after extubation.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the means, the standard deviation (SD), or medians (interquartile range, IQR) as appropriate, and discrete variables as counts (percentages). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test for normality. The independent samples t-test or a Mann–Whitney test was used to compare quantitative variables. A chi-square or Fisher exact test was used to compare qualitative variables if necessary. First, we performed a univariate analysis to identify the explanatory variables (the type of surgery) with a significant contribution to the response variable (the rate of postoperative pain NRS > 3). Afterward, we conducted a multivariate analysis to adjust for covariates with the stepwise method by the Aikake Information Criterion (AIC). A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered significant. The analysis was performed using R software (version 2.6 - 1).

Results

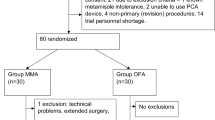

We enrolled 379 consecutive patients who had undergone laparoscopic surgery, 188 in the OFA group and 191 in the control group. Figure 2 shows a diagram flow.

Regarding the first OFA group, 55.3% were female, and the mean age was 61 y (Sd 16).

In the control group, 42.9% were female, with a mean age of 55 y (Sd 16). Table 1 shows surgical procedures and comorbidities.

We observed a statistically significant difference in the hypercholesterolemia, 16% OFA group versus 31.9% control group (p < 000.1). Only one patient in the OFA group, for the failure of RA, received a rescue dose of 0.2 mg of fentanyl IV, followed by continuous infusion of remifentanil. Furthermore, it was necessary to convert from a laparoscopic to an open surgical approach for 10 patients in the intraoperative period; these patients were excluded from the study.

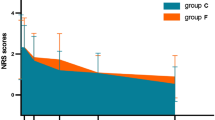

An NRS score > 3 at each time point was recorded in 8 patients (4.2%) in the control group. A significantly lower NRS score at each time point in the OFA group was p < 0.001, as shown in Table 2; Fig. 3.

Moreover, we found a significant difference in the mobilization recovery time, which occurred at 36.00 [18.00, 48.00] hours in the OFA group versus 48.00 [24.00, 72.00] hours in the control group (p < 0.001). We also found a significant difference in the length of stay, 4.00 [2.00, 6.00] days in the OFA group versus 6.00 [4.00, 9.00] days in the control group (p < 0.001), Table 3. Concerning the evaluation of side effects, we found a reduced/null onset in the OFA group compared with the control group. As Table 4 shows, we did not detect other clinically considerable side effects in the OFA group. No ICU admission was recorded in the first 24 h after the end of surgery.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that the use of analgesic abdominal wall blocks (TAP block and RSB) in association only with magnesium sulfate, clonidine, and NSAIDs has ensured adequate intraoperative anesthesia and analgesia. Data from comparisons with controls suggest that the choice of OFA in abdominal surgery has proven effective and safe for pain management in both the intra- and postoperative periods. According to data about the time of mobilization recovery and hospitalization period, the value of the proposed OFA protocol has also been proven in terms of enhanced recovery after surgery and reduced/null adverse effects associated with its application.

Various meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials have provided evidence that magnesium sulfate is effective in reducing23and minimizing postoperative pain if intravenously administered in the perioperative period24.

NSAIDs and Clonidine demonstrate significant opioid-sparing effects and are among the most effective analgesics for postoperative pain control. They showed benefits in several aspects of perioperative rehabilitation, such as reducing pain, nausea, and fatigue and should be (pending any contraindications) part of OFA protocol13.

The only randomized controlled trial that examined the combination of locoregional anesthesia and OFA was conducted by Li et al.25The study compared ultrasound-guided intermediate cervical plexus block (ICBP) with OFA to opioid-based anesthesia in thyroid surgery. The findings indicate that this combined approach resulted in a lower incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), more stable intraoperative hemodynamic conditions, a more effective postoperative analgesic effect, and better quality of recovery 24 h after surgery, in accordance with our achievements25.

Only one retrospective matched case-controlled study26 compared the efficacy in terms of LOS, opioid consumption, postoperative pain hospital cost, and side effects (PONV and respiratory depression) of OFA versus opioid anesthesia in laparoscopic surgery for sleeve gastrectomy. In all, 44 patients, comparable for clinical characteristics (age, height, weight, BMI, sex, ASA score, and comorbidity), were matched and analyzed: OFA group (n = 22) and control group (n= 22). After analyzing the data, no significant differences were found between the groups in any outcome. However, there are still several limitations. In the OFA protocol, ketamine, a drug with analgesic and antihyperalgesic properties, was not used because it was not available27.

Second, opioid consumption and symptoms of PONV in both groups were not analyzed due to the small-matched retrospective nature of the study.

In a randomized controlled double-blind trial, Jarahzadeh et al.28 recruited 60 patients who had undergone abdominal hysterectomies, 30 per group, with intraoperative administration of fentanyl and morphine. Afterward, the intervention group received 50 mg/kg magnesium sulfate versus placebo. Postoperative pain at 1, 2, 6, and 12 h after surgery was lower in the intervention group than in the placebo group, P < 0.001. There was no significant difference concerning side effects in either group.

Salomè et al. compared OFA to opioid-based anesthesia in a meta-analysis that involved 33 RCTs with up to 2,000 participants29. The composite postoperative acute pain and morphine consumption were measured at 2, 24, and 48 h. Secondary outcomes included incidence of chronic pain, hemodynamic tolerance, adverse effects, and opioid-related adverse effects. Their analysis showed no clinically significant benefits in terms of acute episodic pain and rescue opioid use after surgery, but rather a clear benefit in terms of a reduction in side effects, particularly PONV RR of 0.46 (0.38, 0.56) and sedation SMD of − 0.81 (− 1.05; − 0.58) in the OFA group.

In a previous meta-analysis that included 23 trials, Frauenknecht et al.4 recorded postoperative pain with a visual analog scale (VAS, 0–10) at 2 postoperative hours in 2 groups of patients (opioid inclusive versus opioid-free) to investigate whether opioid-inclusive anesthesia reduces postoperative pain without increasing the rate of postoperative nausea and vomiting within the first 24 postoperative hours or the length of stay in the recovery area.

The analysis reported that OFA did not reduce pain scores after surgery (95% CI) of 0.2 (0.2 to 0.5), p = 0.38, and the LOS mean difference (95% CI) was 0.6 (8.2 to 9.3), min, P = 0.90, but it was associated with a decreased rate of PONV risk ratio (95% CI) of 0.77 (0.61–0.97), P = 0.03.

However, the main limitation of these meta-analyses is the large miscellany of OFA techniques.

Opioid Inclusive Anesthesia (OIA) based on continuous remifentanil infusion for breast cancer surgery was compared to OFA based on continuous infusion of ketamine and magnesium in a recent retrospective study by Di Benedetto at al30 They enrolled 51 patients in the OIA group and 38 in the OFA group. Their analysis showed lower NRS scores at 30 min and 6, 12, and 24 h after surgery (P < 0,001) and lower PONV incidence in the OFA group than in the OIA group (P 0.021). In contrast to our study, they evaluated the quality of life using a QoR- 40: no difference in the perception of hospitalization quality between the OFA and the OIA groups was reported.

Few studies have investigated the use of the OFA technique in abdominal surgery. In this prospective randomized study, Gimmel et al.31 compared 60 patients (similar characteristics and PONV risk scores) who underwent general anesthesia with volatile anesthetics and opioids to 60 patients who underwent general opioid-free anesthesia with TIVA (propofol, ketamine, and dexmedetomidine). Using a Likert scale (none, mild, moderate, and severe), the recorded PONV risk in the control group was [P.0.04; risk 1.27 (1.01–1.61)]. Moreover, the severity of PONV was significantly worse.

In agreement with the results of the present study, an OFA approach demonstrated favorable results and appears to be associated with reduced opioid consumption and PONV.

Despite growing evidence, opioids remain the most comfortable choice of a majority of health-care providers in perioperative medicine32.

This first randomized controlled trial about the efficacy and safety of the OFA protocol with abdominal wall block in laparoscopic abdominal surgery showed that the proposed OFA protocol allows adequate postoperative pain control, significantly reducing the side effects of opioids, and, at the same time, improving the length of stay and mobilization compared with the OIA regimen. The block of surgical stress and sympathetic reactions due to the preoperative execution of locoregional anesthesia techniques conditioned the efficacy and safety of the proposed OFA in these patients, guaranteeing the adequacy of intraoperative antinociception.

Moreover, the combined use of a low dose of magnesium sulfate and clonidine ensures hemodynamic stability to surgical stress comparable to that of opioids.

In addition, the OFA protocol has proven valid in both young and older adults, both males and females. Similarly, OFA has been employed for all types of laparoscopic surgical procedures (parietal and visceral) with success in proving that the type of surgery has not significantly influenced the possibility of avoiding opioids.

In the 10 patients who needed an intraoperative shift to an open surgical approach, it was not necessary to administer other and additional drugs. Although open surgery was not included in the field of the study, the poor and incidental clinical records about patients undergoing general anesthesia for open surgery also support the safe use of OFA proposed for this group and suggest an in-depth analysis in a wider group of patients.

Although using TAP block and RSB together may seem redundant, in our experience, this association has ensured a better spread of local anesthetic with full coverage of the abdominal region and also leads to systemic absorption of local anesthetic (LA). Low blood concentrations of LA may have significant beneficial effects related to nociception and opioid requirements, anti-inflammatory effect, ileus duration, and incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting, and consequentially, length of hospital stay and may improve postoperative analgesia and recovery. The systemic effects of OFA with local anesthetics administered IV combined with RA may be clinically relevant for the risk of toxicity.

Our study has some limitations.

First, patient recruitment was monocenter.

Second, postoperative evaluation was empirically fixed at 24 h after surgery. Such a short follow-up time made it impossible to effectively evaluate the efficacy of anesthesia in both groups during in-hospital length of stay.

Third, nonapplication of a specific risk score for PONV was applied.

Fourth, different types of procedures, parietal wall, and surgery involving the viscera could influence the need for intraoperative analgesia.

Lastly, a locoregional anesthetic technique anesthesia is an operator-dependent technique.

Conclusion

This study showed that the preoperative implementation of locoregional anesthesia techniques with OFA guarantees the adequacy of intraoperative antinociception, while only low magnesium sulphate and clonidine ensure hemodynamic stability comparable to opioids during surgery. Our OFA protocol combined with RA reduces the side effects of opioids and decreases patients’ length of stay and early mobilization without requiring additional drugs. Considering the advantages of the opioid-free protocol, we encourage its use. However, further study is needed to confirm our results in other settings and different surgical interventions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from corresponding authors but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Change history

13 June 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02624-5

References

Gerbershagen, H. J., Rothaug, J., Kalkman, C. J. & Meissner, W. Determination of moderate-to-severe postoperative pain on the numeric rating scale: a cut-off point analysis applying four different methods. Br. J. Anaesth. 107, 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aer195 (2011).

Kehlet, H., Jensen, T. S. & Woolf, C. J. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 367, 1618–1625. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68700-x (2006).

Carcamo-Cavazos, V. & Cannesson, M. Opioid-Free anesthesia the pros and cons. Adv. Anesth. 40, 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aan.2022.07.003 (2022).

Frauenknecht, J., Kirkham, K. R., Jacot-Guillarmod, A. & Albrecht, E. Analgesic impact of intra‐operative opioids vs. opioid‐free anaesthesia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Anaesthesia 74, 651–662. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14582 (2019).

Wesmiller, S. W. et al. A prospective study of nausea and vomiting after breast cancer surgery. J. PeriAnesthesia Nurs. 32, 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2015.12.009 (2017).

Exadaktylos, A. K. et al. Can anesthetic technique for primary breast cancer surgery affect recurrence or metastasis?? Anesthesiology 105, 660–664. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200610000-00008 (2006).

Herroeder, S. et al. Magnesium—Essentials for anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology 114, 971–993. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0b013e318210483d (2011).

Shin, H-J., Na, H-S. & Do, S-H. Magnesium and pain. Nutrients 12, 2184. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082184 (2020).

Hadavi, S. M. R. et al. Comparison of Pregabalin with magnesium sulfate in the prevention of remifentanil-induced hyperalgesia in patients undergoing rhinoplasty: A randomized clinical trial. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 7, 1360–1366. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.905 (2022).

Papireddy, B. M., N, S. M., Tarigonda, S. P. & S A comparative study of placebo versus Opioid-Free analgesic mixture for mastectomies performed under general anesthesia along with erector spinae plane block. Cureus 15, e34457. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.34457 (2023).

Hwang, J-Y. et al. I.V. Infusion of magnesium sulphate during spinal anaesthesia improves postoperative analgesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 104, 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aep334 (2010).

Hughes, L. M., Irwin, M. G. & Nestor, C. C. Alternatives to remifentanil for the analgesic component of total intravenous anaesthesia: a narrative review. Anaesthesia 78, 620–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15952 (2023).

BUGADA, D., LORINI, L. F. & LAVAND’HOMME, P. Opioid free anesthesia: evidence for short and long-term outcome. Minerva Anestesiol. 87, 230–237. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0375-9393.20.14515-2 (2021).

Forget, P. & Cata, J. Stable anesthesia with alternative to opioids: are ketamine and magnesium helpful in stabilizing hemodynamics during surgery? A systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Best Pr Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 31, 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2017.07.001 (2017).

Ibrahim, M. et al. Combined opioid free and loco-regional anaesthesia enhances the quality of recovery in sleeve gastrectomy done under ERAS protocol: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 22, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01561-w (2022).

Børglum, J., Gögenür, I. & Bendtsen, T. F. Abdominal wall blocks in adults. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 29, 638–643. https://doi.org/10.1097/aco.0000000000000378 (2016).

Chin, K. J. et al. Essentials of our current Understanding. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 42, 133–183. https://doi.org/10.1097/aap.0000000000000545 (2017).

Tsai, H-C. et al. Transversus abdominis plane block: an updated review of anatomy and techniques. BioMed. Res. Int. 2017, 8284363. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8284363 (2017).

Karaarslan, E., Topal, A., Avcı, O. & Uzun, S. T. Research on the efficacy of the rectus sheath block method. Ağrı - J. Turk. Soc. Algology. 30, 183–188. https://doi.org/10.5505/agri.2018.86619 (2018).

Lim, C-Y. & In, J. Randomization in clinical studies. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 72, 221–232. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.19049 (2019).

Chen, G., Zhou, Y., Shi, Q. & Zhou, H. Comparison of early recovery and cognitive function after desflurane and Sevoflurane anaesthesia in elderly patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Int. Méd Res. 43, 619–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060515591064 (2015).

Deshmukh, P. P. & Chakole, V. Post-Anesthesia recovery: A comprehensive review of Sampe, modified Aldrete, and white scoring systems. Cureus 16, e70935. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.70935 (2024).

Oliveira, G. S. D., Castro-Alves, L. J., Khan, J. H. & McCarthy, R. J. Perioperative systemic magnesium to minimize postoperative pain. Anesthesiology 119, 178–190. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0b013e318297630d (2013).

Mansour, M. A., Mahmoud, A. A. A. & Geddawy, M. Nonopioid versus opioid based general anesthesia technique for bariatric surgery: A randomized double-blind study. Saudi J. Anaesth. 7, 387–391. https://doi.org/10.4103/1658-354x.121045 (2013).

Liu, Z., Bi, C., Li, X. & Song, R. The efficacy and safety of opioid-free anesthesia combined with ultrasound-guided intermediate cervical plexus block vs. opioid-based anesthesia in thyroid surgery—a randomized controlled trial. J. Anesth. 37, 914–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-023-03254-9 (2023).

Ma, Y., Zhou, D., Fan, Y. & Ge, S. An Opioid-Sparing strategy for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A retrospective matched Case-Controlled study in China. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 879831. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.879831 (2022).

Oernskov, M. P., Santos, S. G., Asghar, M. S. & Wildgaard, K. Is intravenous magnesium sulphate a suitable adjuvant in postoperative pain management? – A critical and systematic review of methodology in randomized controlled trials. Scand. J. Pain. 23, 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2022-0048 (2023).

Jarahzadeh, M. H. et al. The effect of intravenous magnesium sulfate infusion on reduction of pain after abdominal hysterectomy under general anesthesia: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Electron. Physician. 8, 2602–2606. https://doi.org/10.19082/2602 (2016).

Salomé, A., Harkouk, H., Fletcher, D. & Martinez, V. Opioid-Free anesthesia Benefit–Risk balance: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Med. 10 (2069). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10102069 (2021).

Benedetto, P. D. et al. Opioid-free anesthesia versus opioid-inclusive anesthesia for breast cancer surgery: a retrospective study. J. Anesth. Analg Crit. Care. 1, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44158-021-00008-5 (2021).

Ziemann-Gimmel, P., Goldfarb, A. A., Koppman, J. & Marema, R. T. Opioid-free total intravenous anaesthesia reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting in bariatric surgery beyond triple prophylaxis. Br. J. Anaesth. 112, 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aet551 (2014).

Sobey, C. M., King, A. B. & McEvoy, M. D. Postoperative ketamine. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 41, 424–426. https://doi.org/10.1097/aap.0000000000000429 (2016).

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GA: conceptualization and writing, original draft preparation. MC and DR: methodology data curation and writing—original draft preparation. SMR and LV visualization and investigation. SMR and AG : supervision. GA: software and validation. GA SMR LV and AG reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study (register n° 118 AOR/29 - 04 - 2019) was approved by the Palermo2 Ethics Committee (n°16/13 - 06 - 2019). All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Table 3 legend. Full information regarding the correction made can be found in the correction notice for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Accurso, G., Rampulla, D., Cusenza, M. et al. A blended opioid-free anesthesia protocol and regional parietal blocks in laparoscopic abdominal surgery- a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 14097 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97116-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97116-x