Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of mortality worldwide, particularly among older adults. Identifying modifiable dietary factors associated with CVD prevalence is essential for prevention. This cross-sectional study analyzed 7,341 adults aged ≥ 65 years from NHANES 2007–2018. CVD was defined based on self-reported physician-diagnosed conditions, including coronary heart disease, heart failure, angina, heart attack, or stroke. A nutrient-wide association study (NWAS) evaluated associations between 56 dietary nutrients and CVD prevalence using multivariable logistic regression. Dose–response relationships were assessed using restricted cubic spline (RCS) models. Model discrimination was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Eight nutrients were significantly associated with CVD prevalence after adjusting for confounders and correcting for multiple comparisons: PUFAs 20:4 (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.80–0.97, P = 0.024), 22:5 (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.56–0.92, P = 0.019), and 22:6 (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.87–0.99, P = 0.032); total choline (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.93–0.99, P = 0.024); cholesterol (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.82–0.96, P = 0.037); protein (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.76–0.89, P = 0.040); vitamin A (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.91–0.99, P = 0.045); and total sugars (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.96–0.98, P = 0.049). Clustering analysis identified protective effects of fat-soluble vitamins and unsaturated fatty acids. The inclusion of these nutrients significantly improved model discrimination (P < 0.05). This study identified key dietary nutrients and clusters associated with CVD prevalence and characterized their dose–response relationships. Integrating these nutrients into predictive models enhances CVD risk discrimination, providing actionable dietary targets for prevention strategies in older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of mortality worldwide, with older adults disproportionately bearing the burden due to both age-related physiological changes and cumulative lifetime risk exposures. In the United States, nearly half of adults aged 60 and above have some form of CVD, including coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke, contributing to significant healthcare costs and loss of life quality. Globally, CVD accounts for over 17.9 million deaths annually, representing 31% of all deaths, with a substantial burden among aging populations in both high-income and low- and middle-income countries1. This demographic transition toward an aging population underscores the urgent need to identify modifiable factors that can mitigate the burden of CVD in older adults.

Nutritional status is a key modifiable determinant in the development and progression of chronic diseases, including CVD, offering a critical avenue for both prevention and management. A growing body of evidence suggests that imbalanced nutrient intake—both deficiencies and excesses—is closely associated with various health outcomes. For instance, inadequate intake of essential micronutrients such as potassium, magnesium, and omega- 3 fatty acids has been linked to increased blood pressure and dyslipidemia, both of which are major risk factors for CVD2,3,4,5. On the other hand, excessive consumption of sodium and saturated fats has been consistently implicated in the pathogenesis of hypertension and atherosclerosis6,7,8. Emerging research also highlights the role of non-nutrient bioactives, such as polyphenols and flavonoids, in cardiovascular health, suggesting the complexity of nutrient-disease interactions9.

The concept of “food as medicine” highlights the intertwined roles of diet in nourishment and disease prevention, a philosophy supported by both historical tradition and contemporary scientific findings. Historical records and modern clinical evidence support the premise that dietary components can serve as both preventive and therapeutic agents in chronic disease management. For example, traditional diets such as the Mediterranean and DASH diets, rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, have demonstrated significant cardiovascular benefits10,11,12. Additionally, bioactive compounds derived from foods, such as curcumin, catechins, and anthocyanins, have been shown to possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, further underscoring the therapeutic potential of diet13,14,15. However, these dietary patterns consist of multiple interacting nutrients, making it difficult to isolate the effects of individual components. To address this complexity, large-scale, systematic approaches such as nutrient-wide association studies (NWAS) and nutrient clustering analyses are needed to identify the most influential dietary factors for CVD prevention.

The NWAS provides a systematic approach to understanding the multifaceted relationships between diverse nutrient exposures and health outcomes. Unlike traditional studies focusing on single nutrients or dietary patterns, NWAS systematically evaluates multiple nutrients simultaneously, allowing for the identification of protective and deleterious nutrient exposures. Additionally, given that nutrients often co-exist in biologically meaningful clusters, an emerging area of research focuses on hierarchical clustering of dietary components, allowing for the assessment of nutrient interactions that may exert synergistic or antagonistic effects on cardiovascular health. This methodological advantage aligns with the multifactorial etiology of CVD, where multiple dietary factors may interact to influence disease risk16. Identifying nutrient-CVD associations can inform public health interventions, including dietary recommendations and supplementation strategies, tailored to the needs of older adults.

Furthermore, this research has the potential to uncover novel insights into nutrient interactions and their roles in cardiovascular health. For example, the synergistic effects of vitamins and minerals, such as the interplay between vitamin D and calcium in vascular function, remain poorly understood but may have profound implications for prevention strategies17,18,19. Similarly, emerging evidence suggests that nutrient metabolism may be influenced by genetic and environmental factors, adding another layer of complexity to understanding nutrient-disease associations20. By integrating NWAS with clustering-based approaches, this study aims to bridge the gap between isolated nutrient research and holistic dietary patterns, offering new insights into how dietary components collectively impact CVD prevalence.

This study investigates the associations between nutrient intake, nutrient clusters, and CVD prevalence among older adults, leveraging the nationally representative NHANES 2007–2018 dataset, renowned for its detailed dietary, biomarker, and health outcome data. NHANES provides a unique opportunity to explore these associations due to its comprehensive dietary data, longitudinal follow-up, and representativeness of the U.S. population. By leveraging both NWAS and hierarchical clustering approaches, this research seeks to identify (1) protective and harmful nutrients, (2) synergistic nutrient clusters, and (3) whether these dietary factors improve CVD risk discrimination. The ultimate goal is to inform precision nutrition strategies that account for individual variability in nutrient needs and responses, enhancing the feasibility and impact of dietary interventions21,22,23.

In addition to its potential public health impact, this study addresses critical gaps in the literature by focusing on older adults, a population that is often underrepresented in nutritional research. The integration of NWAS methodology with NHANES data also represents a novel approach to studying nutrient-disease relationships, offering robust and generalizable findings. By evaluating both individual nutrients and clustered dietary patterns, this study provides a more holistic understanding of dietary contributions to CVD, with the potential to refine dietary guidelines and targeted interventions aimed at reducing cardiovascular risk in aging populations.

Methods

Study design and population

This study utilized a cross-sectional design based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a program specifically developed to assess the health and nutritional status of the United States population. NHANES employs a rigorous, stratified, multistage probability sampling framework to ensure that its findings are generalizable to the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population24. Ethical oversight for NHANES was provided by the institutional review board of the National Center for Health Statistics, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants25. The data, along with detailed protocols and documentation, are publicly available on the NHANES website and adhere to standardized laboratory and anthropometric methodologies consistent with prior studies26,27.

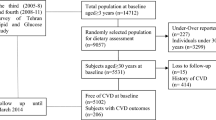

For this prospective cohort study, data spanning five two-year cycles from 2007 to 2018 were screened and analyzed. To ensure the robustness and validity of the results, strict exclusion criteria were implemented: (1) individuals under 65 years of age (n = 51,329); (2) individuals without total nutrient intake measurements (n = 136); (3) individuals without outcome measurement for CVD (n = 3); and (4) individuals missing essential covariate data (n = 0). Following the application of these criteria, 7,341 participants from the 2007 to 2018 cycles were included in the final analytic cohort (Fig. 1).

Assessment of dietary nutrient intakes

The primary variable of interest in this study was nutrient intake, assessed using a rigorous 24-h dietary recall methodology. This approach provided comprehensive information on participants’ nutrient and energy consumption, enabling detailed subsequent analyses. Dietary data were collected from each participant through two separate 24-h recall sessions. The initial recall was conducted in person at a mobile examination center, ensuring a controlled environment for data collection. The second recall occurred via telephone within 3 to 10 days of the first, allowing for temporal variability in dietary intake. Nutrient intake data were processed and standardized using the Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS), a resource developed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), ensuring consistency and accuracy in dietary analysis. The abbreviations of the nutrients, along with their full names, are provided in Table S1.

Assessment of CVD

CVD was defined as the presence of any of the following conditions: heart failure, coronary heart disease (CHD), angina, heart attack, or stroke. These conditions were identified based on participant responses to specific survey questions: heart failure (MCQ160b), coronary heart disease (MCQ160c), angina (MCQ160 d), heart attack (MCQ160e), and stroke (MCQ160f.). For the purpose of this study, individuals with a self-reported diagnosis of any of these conditions were classified as having CVD.

Covariates

The following covariates were included in this study: age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, family poverty-to-income ratio (PIR), body mass index (BMI), smoking status, drinking status, hypertension, and diabetes.

BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2) and classified into four categories: underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25), overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30), and obesity (BMI ≥ 30). Smoking status was determined based on participants’responses to two questionnaire items:"Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your life?"(SMQ020) and"Do you currently smoke cigarettes?"(SMQ040). Participants were categorized as smokers if they answered“yes”to either question.

Drinking status was assessed using the questionnaire item"Have you had at least 12 alcoholic drinks in any given year?"(ALQ101). Participants were classified as drinkers if they reported consuming at least 12 alcoholic drinks per year. One unit of alcohol was defined as 12 oz of beer, 5 oz of wine, or 1.5 oz of distilled spirits.

Hypertension and diabetes were determined based on self-reported responses to specific questionnaire items. Hypertension was assessed using the question"Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have high blood pressure?"(BPD035). Diabetes mellitus was identified using the question"Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have diabetes?"(DIQ010).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina, USA) and R software (version 4.3.1; https://www.R-project.org). Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage, while continuous variables were represented as mean and standard deviation (SD). A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

First, CVD was used as the outcome variable in a multivariable logistic regression model that included 10 covariates (age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, PIR, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, hypertension, and diabetes) to identify significant confounders associated with CVD. Second, adjusting for these covariates and total energy intake, 56 individual nutrients were sequentially included in the regression models to screen for nutrients significantly associated with CVD. P-values were corrected using the false discovery rate (FDR) method with the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure28. Next, restricted cubic spline (RCS) analyses were employed to investigate dose–response relationships between the identified nutrients and the prevalence of CVD. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the strength and direction of these associations29. Finally, the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) was evaluated to compare the discriminatory power for CVD using models that included only covariates versus models incorporating the identified nutrient markers. To address missing data for covariates, excluding the exposure and outcome variables, multiple imputations with five imputed datasets were performed30.

Results

Study population characteristics

The study included 7,341 participants, of whom 2,033 (27.7%) had CVD (Table 1). Participants with CVD were older (mean age 74.58 vs. 72.94 years, P < 0.001) and had a lower poverty-to-income ratio (PIR) compared to non-CVD participants (mean 2.31 vs. 2.50, P < 0.001). Men constituted a higher proportion of the CVD group (59.7%) compared to the non-CVD group (45.9%, P < 0.001). CVD was more prevalent among participants with a high school education or less (59.1% vs. 53.1%, P < 0.001) and among Non-Hispanic Whites (61.8% vs. 52.6%, P < 0.001). Smoking status was significantly associated with CVD, with a higher percentage of smokers in the CVD group (12.1% vs. 8.9%, P < 0.001). Participants with CVD had a higher prevalence of diabetes (28.0% vs. 17.1%, P < 0.001) and obesity (39.1% vs. 35.0%, P < 0.001) compared to those without CVD. Differences in BMI categories were also observed, with higher obesity prevalence in the CVD group (39.1% vs. 35.0%, P < 0.001).

Associations between traditional risk factors and CVD

The associations between traditional risk factors and CVD are summarized in Table 2. Older age was significantly associated with higher odds of CVD (OR 1.07; 95% CI, 1.05–1.08; P < 0.001). Men had over twice the odds of CVD compared to women (OR 2.03; 95% CI, 1.73–2.38; P < 0.001). Lower PIR and lower education levels were associated with increased odds of CVD (PIR: OR 0.94; 95% CI, 0.89–0.99; P = 0.015; education: OR 0.81; 95% CI, 0.69–0.95; P = 0.012). Racial disparities were evident, with Non-Hispanic White participants (OR 1.66; 95% CI, 1.35–2.03; P < 0.001) and participants of other races (OR 1.71; 95% CI, 1.22–2.40; P = 0.003) having higher odds of CVD compared to Mexican Americans. Smoking was strongly associated with increased odds of CVD (OR 1.73; 95% CI, 1.31–2.26; P < 0.001), and obesity also elevated the odds (OR 1.24; 95% CI, 1.02–1.50; P = 0.030). Hypertension and diabetes were the strongest risk factors, with hypertension more than doubling the odds of CVD (OR 2.09; 95% CI, 1.74–2.52; P < 0.001) and diabetes increasing the odds by 89% (OR 1.89; 95% CI, 1.57–2.28; P < 0.001).

Nutrient intake in participants with and without CVD

The distribution of daily dietary intake for 56 nutrients among participants with and without CVD is detailed in Table S2. Participants with CVD had significantly lower energy intake compared to those without CVD (mean 1,725.34 vs. 1,776.02 kcal; P = 0.010). Similarly, protein intake was lower in the CVD group (mean 66.58 vs. 69.72 g; P < 0.001), as was carbohydrate intake (mean 211.54 vs. 217.31 g; P = 0.020). Dietary fiber intake was notably reduced in participants with CVD (mean 15.04 vs. 16.45 g; P < 0.001), while total fat intake did not differ significantly between groups (P = 0.190). Among micronutrients, participants with CVD had lower beta-carotene (mean 2,040.02 vs. 2,467.21 mcg; P < 0.001) and lutein + zeaxanthin intake (mean 1,275.64 vs. 1,670.34 mcg; P < 0.001). Vitamin K intake was also significantly reduced in the CVD group (mean 92.34 vs. 114.72 mcg; P < 0.001). In contrast, some nutrients showed no significant differences, such as total sugars, cholesterol, and vitamin B12. Obesity-related nutrients such as total saturated fatty acids and total polyunsaturated fatty acids were comparable between groups.

Correlation analysis and hierarchical clustering analysis of 56 nutrient intakes

We analyzed nutrient correlations within NHANES 2007–2018, identifying significant relationships among dietary components (Figure S1). Correlation coefficients (r) ranged from − 0.42 to 0.82, reflecting varying degrees of positive and negative associations between macronutrients, vitamins, and minerals. For example, dietary fiber showed strong positive correlations with vitamin C (r = 0.64, P < 0.001) and magnesium (r = 0.58, P < 0.001), while saturated fat intake demonstrated weak or inverse correlations with these micronutrients (e.g., r = − 0.21 with vitamin C, P < 0.001). Sodium intake exhibited an inverse correlation with potassium (r = − 0.33, P < 0.001). The majority of correlations were statistically significant (P < 0.001), underscoring robust interconnections among nutrients.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of 56 dietary nutrients revealed distinct nutrient groupings based on their biochemical properties and physiological functions (Figure S2, Table S3). Six major clusters were identified. Cluster 1, comprising macronutrients, included protein, carbohydrates, sugars, fiber, total fat, and cholesterol, reflecting their central role in energy metabolism and structural functions. Cluster 2 encompassed fat-soluble vitamins (e.g., vitamin A, retinol, and vitamin D2/D3), highlighting their shared absorption and storage mechanisms. Cluster 3 grouped water-soluble vitamins, including B vitamins, folate, and vitamin C, which are primarily involved in enzymatic reactions and antioxidant functions. Cluster 4, consisting of minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, and iron, underscored their critical roles in bone health, electrolyte balance, and enzymatic activity. Cluster 5 included various saturated fatty acids (SFAs), while Cluster 6 comprised monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs and PUFAs), emphasizing their structural and metabolic differences. These findings underscore the complex interrelationships among nutrients and the need to account for nutrient clustering in dietary research.

Associations between 56 nutrients, nutrient clusters and CVD

Among the nutrients assessed in the study participants, eight were significantly associated with reduced CVD prevalence after adjusting for confounders and correcting for multiple comparisons (Table S4). These included polyunsaturated fatty acids (docosapentaenoic acid, eicosatetraenoic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid), total choline, dietary protein, cholesterol, vitamin A (retinol activity equivalents), and total sugars. Odds ratios ranged from 0.72 to 0.97, with FDR-adjusted P-values between 0.019 and 0.049. These findings highlight the potential cardioprotective effects of specific nutrients, underscoring the importance of dietary composition in reducing CVD prevalence. Future research is warranted to validate these associations and explore underlying mechanisms.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis examining the associations between risk scores for dietary nutrient clusters and cardiovascular disease (CVD) revealed significant findings (Table 3). Higher intake of fat-soluble vitamins (Cluster 2, OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.85–0.99, P = 0.048) and water-soluble vitamins (Cluster 3, OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84–0.96, P = 0.041) was associated with a reduced risk of CVD after multiple comparison adjustments, suggesting potential protective effects. In contrast, higher intake of saturated fatty acids (Cluster 5, OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.02–1.22, P = 0.010) was significantly associated with increased CVD risk. Unsaturated fatty acids (Cluster 6, OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.58–0.94, P = 0.032) exhibited a protective association with CVD, further supporting the cardiovascular benefits of these nutrients. Notably, the interaction term between fat-soluble vitamins and unsaturated fatty acids (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78–0.95, P = 0.035) suggested a potential synergistic effect in reducing CVD risk. These findings highlight the importance of dietary patterns that emphasize vitamins and unsaturated fats while minimizing saturated fat intake for CVD prevention.

Sensitivity analyses stratified by sex, race/ethnicity, and body weight status demonstrated results largely consistent with the main analysis (Table S5 and Table S6). The associations between polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) 22:5 and 22:6, total choline, cholesterol, protein, and total sugars with CVD risk remained robust across subgroups, confirming the stability of our findings.

Dose–response relationships between identified nutrients and CVD

The RCS models were employed to investigate potential nonlinear associations between nutrient intakes and CVD prevalence, adjusting for energy intake, age, sex, race, education level, PIR, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, hypertension, and diabetes (Fig. 2). The analysis demonstrated that increased intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) 20:4 (Fig. 2A), 22:5 (Fig. 2B), and 22:6 (Fig. 2C), as well as vitamin A (Fig. 2G), was associated with a lower estimated prevalence of CVD. However, the confidence intervals for these relationships were not statistically significant, and no evidence of nonlinear relationships was observed (P > 0.05). For total choline (Fig. 2D), cholesterol (Fig. 2E), and protein (Fig. 2F), a dual effect was observed. Threshold values were identified for these nutrients: 264.6 mg/day for total choline, 196 mg/day for cholesterol, and 65 g/day for protein. Intake levels below these thresholds were associated with an increased prevalence of CVD, while intake levels above the thresholds were associated with a decreased prevalence of CVD. Finally, total sugars (Fig. 2H) exhibited a significant positive linear association with CVD prevalence (P for overall association = 0.002), although no significant nonlinear relationship was detected (P > 0.05).

Restrictive cubic spline analysis was conducted to examine the dose–response relationships between 8 significant nutrient-related markers and the risk of cardiovascular disease. The markers included: (A), PFA 20:4 (Eicosatetraenoic); (B), PFA 22:5 (Docosapentaenoic); (C), PFA 22:6 (Docosahexaenoic); (D), total choline; (E), cholesterol; (F), protein; (G), vitamin A (RAE); and (H), total sugars. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

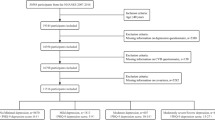

Improved discrimination of the identified nutrients, dietary clusters, and their interactions for CVD prevalence

In this study, we evaluated whether incorporating the identified eight nutrients and nutrient clusters could improve the discriminative ability of models for CVD prevalence. Discriminant analysis was performed to compare the predictive performance of three models (Fig. 3). Model 1 included only conventional covariates, such as energy intake, age, sex, race, education level, PIR, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, hypertension, and diabetes. Model 2 incorporated the same covariates as Model 1, along with the eight significant nutrients, including PFA 22:5, PFA 20:4, total choline, PFA 22:6, cholesterol, protein, vitamin A, and total sugars. Model 3 included the same covariates as Model 1 but instead integrated four significant nutrient clusters (fat-soluble vitamins, water-soluble vitamins, saturated fatty acids, and unsaturated fatty acids) and one nutrient interaction (fat-soluble vitamins*unsaturated fatty acids).

Improved discrimination for cardiovascular disease (CVD) was achieved through the selection of (A) 8 significant nutrient-related markers and (B) 4 significant nutrient clusters with 1 nutrient interaction. Eight significant nutrient-related markers include PFA 22:5 (Docosapentaenoic), PFA 20:4 (Eicosatetraenoic), total choline, PFA 22:6 (Docosahexaenoic), cholesterol, protein, vitamin A (RAE), and total sugars. Four significant nutrient clusters and their interaction include fat-soluble vitamins, water-soluble vitamins, saturated fatty acids, unsaturated fatty acids, and fat-soluble vitamins*unsaturated fatty acids. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to compare the discrimination performance of two models for distinguishing participants with CVD from those without. Model 1 included energy, age, PIR, sex, education level, race, drinking status, smoking status, body mass index, hypertension, and diabetes. Model 2 incorporated the same covariates as Model 1, along with the 8 selected nutrients. Model 3 incorporated the same covariates as Model 1, along with the 4 significant nutrient clusters. RAE, retinol activity equivalents; PIR, family poverty-to-income ratio; PFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids.

The findings revealed that both Model 2 and Model 3 significantly improved discrimination compared to Model 1, as demonstrated by a higher area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) (P < 0.05 for both comparisons using the Delong test). Notably, Model 3 exhibited even greater predictive improvement compared to Model 1, suggesting that nutrient clustering may enhance risk prediction by capturing synergistic effects between related nutrients.

Discussion

This study systematically investigated the relationships between dietary nutrient intake and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevalence among older adults using a nutrient-wide association study (NWAS) approach. Eight nutrients—polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) 20:4, 22:5, and 22:6; total choline; cholesterol; protein; vitamin A; and total sugars—were identified as significantly associated with CVD prevalence after adjusting for confounders and correcting for multiple comparisons. Notably, this study also revealed dose–response relationships for these nutrients and demonstrated their ability to improve the discrimination of CVD prevalence. Furthermore, when nutrients were analyzed in clusters, we identified significant associations between certain dietary patterns and CVD prevalence. In particular, fat-soluble vitamins and unsaturated fatty acids showed a protective effect, whereas saturated fatty acids were positively associated with CVD prevalence. These findings underscore the complexity of dietary contributions to cardiovascular health and highlight specific nutritional targets for prevention and management strategies in aging populations.

The study population characteristics reveal the multifactorial nature of CVD prevalence in older adults. Consistent with prior research, participants with CVD were older, had lower socioeconomic status (as indicated by the poverty-to-income ratio), and exhibited higher prevalence of traditional risk factors such as smoking, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. These findings align with the well-established role of demographic, socioeconomic, and lifestyle factors in shaping CVD risk profiles1,31. The higher prevalence of CVD in men and individuals with lower educational attainment also reflects broader population-level disparities, emphasizing the need for targeted prevention efforts.

This study confirmed the strong associations between traditional risk factors and CVD, including age, sex, smoking, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. These factors collectively accounted for substantial variability in CVD outcomes, underscoring their importance as covariates in multivariable models. For example, hypertension more than doubled the odds of CVD, consistent with meta-analyses demonstrating its role as a primary driver of atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular complications32,33. Similarly, the strong association between diabetes and CVD corroborates evidence linking hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and chronic inflammation to vascular dysfunction34. These results reinforce the necessity of addressing these modifiable risk factors in CVD prevention strategies. Additionally, hierarchical clustering analysis revealed six distinct dietary clusters, with macronutrients, vitamins, and fatty acids forming separate groups. The associations observed at the individual nutrient level were largely consistent when analyzed at the cluster level, reinforcing the robustness of our findings.

The correlation analysis highlighted significant interrelationships among the 56 assessed nutrients, reflecting the intricate interactions inherent in dietary patterns. For instance, dietary fiber’s strong positive correlation with magnesium and vitamin C is indicative of diets rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Conversely, inverse correlations between saturated fats and these micronutrients suggest the predominance of processed and high-fat foods in certain dietary patterns. Recognizing these correlations was critical for the logistic regression modeling, as each nutrient was evaluated independently while adjusting for potential confounders. This approach minimized collinearity issues and allowed for the identification of individual nutrient contributions to CVD prevalence.

The restricted cubic spline analysis provided nuanced insights into the dose–response relationships between nutrient intake and CVD prevalence. While higher intakes of PUFAs 20:4, 22:5, and 22:6, as well as vitamin A, were generally associated with lower CVD prevalence, their confidence intervals lacked statistical significance. However, threshold effects were identified for total choline, cholesterol, and protein, with protective associations observed above specific intake levels. The linear relationship between total sugars and increased CVD prevalence further underscores the adverse impact of excessive sugar consumption. Sensitivity analyses across subgroups (e.g., sex, race, BMI categories) demonstrated consistent associations between these key nutrients and CVD prevalence, with no significant heterogeneity observed in most cases. However, some variations were noted, particularly among different racial groups and between men and women, suggesting potential differences in nutrient metabolism or dietary behaviors across populations. Importantly, incorporating the eight identified nutrients into predictive models significantly improved their discriminatory performance, demonstrating their potential utility as biomarkers for CVD risk stratification.

The observed associations between PUFAs 20:4, 22:5, and 22:6 and reduced CVD prevalence align with existing evidence supporting their anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective properties. These long-chain omega- 3 and omega- 6 fatty acids modulate lipid metabolism, reduce endothelial dysfunction, and attenuate systemic inflammation—key mechanisms implicated in atherogenesis35,36,37. For instance, docosahexaenoic acid (PUFA 22:6) has been shown to lower triglycerides and improve arterial compliance, while eicosatetraenoic acid (PUFA 20:4) influences eicosanoid production, balancing pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators38. Vitamin A’s protective role may stem from its antioxidant properties and involvement in immune regulation. Retinol and its derivatives influence vascular integrity and mitigate oxidative stress, which are critical factors in preventing plaque formation39.

The dual effects of total choline, cholesterol, and protein on CVD prevalence highlight the complexity of their biological roles. Choline is a precursor for acetylcholine and phosphatidylcholine, compounds essential for vascular function and lipid metabolism. However, excessive choline intake may contribute to trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) production, which has been implicated in atherosclerosis40. Similarly, cholesterol intake’s protective effects at moderate levels likely reflect its role in cell membrane integrity and steroid hormone synthesis, while excessive intake can exacerbate dyslipidemia and cardiovascular risk41. Dietary protein’s benefits may derive from its effects on muscle preservation and metabolic health, though excessive intake could contribute to renal strain and metabolic dysregulation42. At the dietary pattern level, we observed that clustering these nutrients together—particularly within the fat-soluble vitamin and unsaturated fatty acid cluster—further enhanced their predictive value for CVD prevalence, suggesting synergistic effects among these components.

The positive association between total sugars and CVD prevalence is consistent with extensive evidence linking high sugar consumption to metabolic syndrome, obesity, and type 2 diabetes—key precursors to CVD43,44,45. Excessive sugar intake promotes insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and systemic inflammation, exacerbating vascular damage. Reducing added sugars in the diet remains a cornerstone of public health recommendations to combat CVD46,47. Moreover, cluster-based analyses confirmed that macronutrient-heavy dietary patterns, particularly those high in sugars and saturated fats, were linked to an increased prevalence of CVD, reinforcing the importance of dietary balance rather than isolated nutrient modifications.

This study has several strengths, including its use of nationally representative NHANES data, robust dietary assessment methods, and rigorous statistical analyses. The NWAS approach enabled the identification of both protective and harmful nutrients, providing a comprehensive perspective on dietary contributions to CVD prevalence. However, the study has limitations, including its cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inference, and potential recall bias in dietary assessments and self-reported CVD diagnoses. Additionally, residual confounding from unmeasured variables cannot be excluded, and the findings may not generalize to non-U.S. populations. Longitudinal studies and randomized trials are needed to validate these associations and elucidate underlying mechanisms.

Conclusion

This study highlights the critical role of dietary nutrient intake in modulating CVD prevalence among older adults. By identifying eight key nutrients and characterizing their dose–response relationships, as well as evaluating nutrient clusters and interactions, this research provides actionable insights for dietary interventions and public health strategies. The findings suggest that specific nutrient clusters, particularly fat-soluble vitamins and unsaturated fatty acids, may have synergistic protective effects against CVD, while dietary patterns high in sugars and saturated fats are associated with increased CVD prevalence. Additionally, integrating these nutrient markers and clusters into predictive models significantly improved their discriminatory power for identifying individuals at risk of CVD. Future research should explore the interplay between nutrient metabolism, genetic predisposition, and environmental factors to refine precision nutrition approaches, develop more targeted dietary recommendations, and optimize cardiovascular health in aging populations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Additionally, all data, codebooks, and analytic code are also publicly accessible to researchers worldwide at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

References

Benjamin, E. J. et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 update: A Report from the American Heart association. Circulation 139, e56–e528. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000659 (2019).

Polonia, J. & Martins, L. A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J. Hum. Hypertens. 23, 771–772. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2009.64 (2009).

Wang, X. et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 349, g4490. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g4490 (2014).

Mozaffarian, D. et al. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 624–634. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1304127 (2014).

Larsson, S. C., Orsini, N. & Wolk, A. Dietary potassium intake and risk of stroke: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Stroke 42, 2746–2750. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.111.622142 (2011).

Micha, R. et al. Association between dietary factors and mortality from Heart Disease, Stroke, and type 2 Diabetes in the United States. JAMA 317, 912–924. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.0947 (2017).

Martínez-González, M. A. et al. Benefits of the mediterranean Diet: insights from the PREDIMED study. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 58, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2015.04.003 (2015).

Lichtenstein, A. H. et al. Summary of American Heart Association Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 2186–2191. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.0000238352.25222.5e (2006).

Wan, S. et al. The Effect of antioxidant polyphenol supplementation on Cardiometabolic risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16234206 (2024).

Appel, L. J. et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 1117–1124. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199704173361601 (1997).

Pasanisi, P. et al. Metformin treatment with or without mediterranean diet for the prevention of age-related Diseases in people with Metabolic Syndrome: The MeMeMe randomized trial. Diabetes Care https://doi.org/10.2337/dc24-1597 (2024).

Hu, F. B. Plant-based foods and prevention of cardiovascular disease: an overview. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 78, 544s–551s. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/78.3.544S (2003).

Zhang, A., Sun, H., Wang, P., Han, Y. & Wang, X. Modern analytical techniques in metabolomics analysis. Analyst 137, 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1an15605e (2012).

Liu, R. H. Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 78, 517s–520s. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/78.3.517S (2003).

Zhou, X. et al. Efficacy and safety of Chinese patent medicine Xiao Yao San in polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 313, 116517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2023.116517 (2023).

Willett, W. C. & Stampfer, M. J. Current evidence on healthy eating. Annu. Rev. Public Health 34, 77–95. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124646 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. Micro/nano-encapsulation of marine dietary oils: A review on biomacromolecule-based delivery systems and their role in preventing cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 261, 129820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129820 (2024).

Pál, É., Ungvári, Z., Várbíró, S., Bereczki, D. & Benyó, Z. Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for cerebrovascular diseases. Orv. Hetil. 165, 1958–1968. https://doi.org/10.1556/650.2024.32962 (2024).

González-Quijano, G. K. et al. Effect of Genotype on the Response to Diet in Cardiovascular Disease-A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel) 12, 2292. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12222292 (2024).

Wang, P., Gao, X., Willett, W. C. & Giovannucci, E. L. Socioeconomic status, diet, and behavioral factors and Cardiometabolic Diseases and Mortality. JAMA Netw Open 7, e2451837. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.51837 (2024).

Ioannidis, J. P. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2, e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124 (2005).

Mozaffarian, D. Dietary and policy priorities for Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetes, and Obesity: A Comprehensive review. Circulation 133, 187–225. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.115.018585 (2016).

Gai, W., Lin, L., Wang, Y., Bian, J. & Tao, Y. Relationship between dietary fiber and all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nephrol 37, 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-023-01808-4 (2024).

Curtin, L. R. et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: Sample design, 2007–2010. Vital Health Stat. 2, 1–23 (2013).

Skrivankova, V. W. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian randomization: The STROBE-MR statement. JAMA 326, 1614–1621. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.18236 (2021).

Yan, Y. et al. The association between triglyceride glucose index and arthritis: a population-based study. Lipids Health Dis. 22, 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-023-01899-9 (2023).

Yan, Y. et al. The association between remnant cholesterol and rheumatoid arthritis: insights from a large population study. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02033-z (2024).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R Stat Soc. B 57, 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x (1995).

Desquilbet, L. & Mariotti, F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat. Med. 29, 1037–1057. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3841 (2010).

Sterne, J. A. et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 338, b2393. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2393 (2009).

Virani, S. S. et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 143, e254–e743. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000950 (2021).

Abariga, S. A., Khachan, H. & Al Kibria, G. M. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension in India Based on the 2017 ACC/AHA Guideline: Evidence from the India National family health survey. Am. J. Hypertens. 33, 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpz181 (2020).

Al Kibria, G. M. Racial/ethnic disparities in prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension among US adults following application of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline. Prev Med Rep 14, 100850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100850 (2019).

Rao Kondapally, S. S. et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 829–841. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1008862 (2011).

Calder, P. C. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Nutrition or pharmacology?. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 75, 645–662. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04374.x (2013).

Harris, W. S. et al. Omega-6 fatty acids and risk for cardiovascular disease: A science advisory from the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 119, 902–907. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.108.191627 (2009).

Mozaffarian, D. & Wu, J. H. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: Effects on risk factors, molecular pathways, and clinical events. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 58, 2047–2067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.063 (2011).

Dyall, S. C. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and the brain: A Review of the independent and shared effects of EPA. DPA and DHA. Front. Aging Neurosci. 7, 52. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2015.00052 (2015).

Semba, R. D. et al. Oxidative stress and severe walking disability among older women. Am. J. Med. 120, 1084–1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.028 (2007).

Tang, W. H. et al. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1575–1584. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1109400 (2013).

Mensink, R. P., Zock, P. L., Kester, A. D. & Katan, M. B. Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: A meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 77, 1146–1155. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1146 (2003).

Wolfe, R. R., Miller, S. L. & Miller, K. B. Optimal protein intake in the elderly. Clin. Nutr. 27, 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2008.06.008 (2008).

Malik, V. S. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Dia. Care 33, 2477–2483. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-1079 (2010).

Johnson, R. K. et al. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 120, 1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.109.192627 (2009).

Stanhope, K. L. Sugar consumption, metabolic disease and obesity: The state of the controversy. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 53, 52–67. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408363.2015.1084990 (2016).

Te Morenga, L., Mallard, S. & Mann, J. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ 346, e7492. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e7492 (2012).

Huang, Y. et al. Dietary sugar consumption and health: umbrella review. BMJ 381, e071609. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-071609 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the leaders of the Panzhihua Central Hospital for their full support during the implementation of the project.

Funding

The research received financial support from the Panzhihua Central Hospital. The findings and conclusions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. No private sponsors were involved in the decision to design the study, collect data, analyze or interpret data, write reports, or submit manuscripts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—Wen Li contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing – original draft, and project administration; Xiaoxia Meng was responsible for conceptualization, visualization and methodology. Huaman Liu was responsible for funding acquisition and investigation. Siqi Liu was responsible for supervision, validation and writing – review & editing. All authors declare that they have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Liu, S., Meng, X. et al. A nutrient wide association study of cardiovascular disease prevalence in older adults from NHANES 2007 to 2018. Sci Rep 15, 12710 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97143-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97143-8