Abstract

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) represents a major subtype of kidney cancer with variable prognosis. A comprehensive understanding of sex hormone-related pathways could potentially refine the prediction of patient outcomes in ccRCC. Patients from TCGA-KIRC (n = 528) and GSE22541 (n = 40) cohorts were analyzed. Sex-hormone-associated pathways were manually collected and calculated with the activated score, then subtypes were identified. Differential gene expression, pathway enrichment, and tumor-infiltrating immunocytes were assessed. A prognostic signature was developed using Cox analysis and LASSO regression. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed to validate the protein level of key model gene in ccRCC tissues. Three distinct subtypes (C1, C2, C3) based on sex hormone pathway activation were discovered. C1 showed the most favorable prognosis (P = 0.00029). 1,094 genes were upregulated in C1 and 197 in C3. 20 risk-associated and 172 protective genes for ccRCC prognosis were identified. LASSO regression narrowed down to 33 genes for the sex-hormone-related-gene (SHAG) prognostic model. In the TCGA-KIRC cohort, the high-SHAG score group had a worse prognosis with an HR of 3.26 (95% CI: 2.334–4.555, P < 0.001). Validation in the GSE22541 cohort corroborated these findings. The nomogram incorporating the SHAG model demonstrated robust predictive accuracy higher than 0.75. IHC validation confirmed that ARHGEF17 protein levels were higher in early-stage ccRCC (stage I-II) compared to advanced-stage (stage III) tumors, supporting its prognostic relevance. The SHAG signature serves as a promising prognostic tool for ccRCC, providing insights into the role of sex hormone-related pathways in tumor progression. Further experimental and clinical validation is warranted to explore its potential in personalized therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is currently one of the major factors affecting human life and health, and urological cancers are one of the more common ones. renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common type of cancer in the urinary system, with clear cell RCC (ccRCC) being the most common subtype1,2. ccRCC is usually divided into four pathological stages, with the fourth stage having the worst prognosis and a survival rate of high to 20%. In the latest cancer report, the number of new cases of RCC diagnosed in the United States has increased to 80,980 in 2025, also with approximately 14,510 deaths, this shows that ccRCC has a high morbidity and mortality rate3. The distinguishing characteristic of ccRCC is the polygonal morphologies containing clear cytoplasm rich in carbohydrates and lipids. Available studies suggest that this is due to a deletion in the short arm of chromosome 3 and mutations in the tumour suppressor gene (VHL) and its resulting overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)4,5. ccRCC is usually treated with surgery and medication. For surgical treatment, chemotherapy is administered postoperatively with cytokines including high-dose interleukin 2 (HDIL- 2) and interferon (IFN)-α. ccRCC is usually cured by surgical resection if it has not metastasised, while metastatic ccRCC still has a high mortality rate after surgery6. Current drug treatments work mainly by acting on targets and include the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab, which acts on VEGF, sorafenib, sunitinib, pazopanib, axitinib, cabozantinib and lenvatinib, which act on the target of rapamycin (mTOR), and tesilomycin and everolimus inhibitors, which act on the target of rapamycin (mTOR)7. Long-term use of existing drugs can cause cells to develop some resistance to them. The identification of key pathways and key genes plays an important role in the diagnosis of renal clear cell carcinoma and in the research of new drugs, as new therapeutic approaches and drugs are urgently needed due to the limitations of existing treatments.

RCC is among the most heavily immune-infiltrated tumors, with the characteristics of its tumor microenvironment not only influencing tumor initiation and progression but also potentially affecting responses to systemic therapies8,9. Compared to untreated patients, ccRCC samples from those receiving bevacizumab treatment exhibit reduced microvascular density, along with a decreased presence of CD68-positive macrophages and chymase-positive mast cells10. Additionally, in RCC patients, the overexpression of miR- 29b and miR- 198 in CD8 + T cells downregulates JAK3 and MCL- 1, leading to immune dysfunction. A study analyzing multi-omics data of ccRCC further confirmed that ccRCC constitutes a highly heterogeneous group of tumors. The immune-exhausted subtype, characterized by a depleted immune microenvironment and activated hypoxic features, is associated with the poorest prognosis; The immune “cold” subtype, predominantly defined by frequent VHL and PBRM1 mutations, exhibits a more favorable prognosis and responds well to sunitinib treatment; Meanwhile, the immune “hot” subtype, marked by immune cell activation, is more responsive to anti-PD- 1 therapy11. The aberrant activation of multiple metabolic pathways in RCC further contributes to tumor progression. In ccRCC, the kynurenine pathway enzymes and their catabolic metabolites are significantly upregulated and serve as independent prognostic factors associated with poor outcomes12. A study revealed that patients with ccRCC exhibit increased levels of creatine, alanine, lactate, and pyruvate, while hippuric acid, citric acid, and betaine are significantly reduced13. Available studies show that RCC is much more common in men than in women, about twice as common as in women14. It is therefore speculated that RCC may be associated with sex hormones including progesterone, estrogen and androgen. Existing studies have also confirmed the presence of progesterone, estrogen and androgen loci in RCC tissue. For progestins we found that PAQR5, which belongs to the class II progestin and adipoQ receptor(PAQR) family, was downregulated in ccRCC and associated with disease exacerbation and poor outcome15. For androgens (AR) we found that AR exacerbates disease by altering circHIAT1/miR- 195 - 5p/29a- 3p/29c- 3p/CDC42 signaling, promoting migration and invasion of ccRCC, which may help open up new therapies to inhibit ccRCC metastasis16,17. For estrogen receptor β (ERβ), which increases cancer stem cell (CSC) populations in ccRCC by altering ERβ/circPHACTR4/miR- 34b- 5p/c-Myc signaling, and targeting this newly discovered signaling pathway may help physicians better inhibit ccRCC progression. Also promoting ccRCC cell invasion by altering the ERβ/circATP2B1/miR- 204 - 3p/FN1 axis, therapeutic targeting of this newly discovered pathway may better halt ccRCC progression18,19. It can be seen that sex hormones play an important role in the pathological mechanism and prognosis of ccRCC, and the existing models of sex hormone regulation of renal clear cell carcinoma development and prognosis prediction are still immature, therefore we conducted a study on the mechanism of sex hormone pathway regulation of renal clear cell carcinoma development and the construction of a prognosis prediction model.

In our research, we included 659 samples from the TCGA-KIRC and GSE22541 cohorts in this study, and we used the TCGA-KIRC cohort to construct the model and then tested its validity with the GSE22541 cohort. In the TCGA-KRIC cohort, we assessed differences in the activation of sex hormone-related pathways between patients and ultimately selected 32 genes to construct a model to predict the prognosis of ccRCC, and this was validated in the GSE22541 cohort.

Methods

Summary of patients

In this investigation, a total of 568 ccRCC patients were enrolled. Specifically, we sourced gene expression profiles and associated clinical data for 528 patients from the TCGA-KIRC cohort via the UCSC Xena platform (http://xena.ucsc.edu/). We used the GENCODE27 annotation document to define mRNA gene symbols. The TPM expression data of mRNA was first transformed by log2 calculation. In addition, we incorporated data from 40 ccRCC patients from the GSE22541 cohort, retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) platform (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Comprehensive baseline data for patients across both cohorts are presented in Table 1.

Remove batch effects between cohorts

To harmonize the datasets from the TCGA-KIRC and GSE22541 cohorts, we addressed and mitigated potential non-biological biases to ensure comparability in gene expression profiles across cohorts. We employed the ComBat algorithm from the R “SVA” package to correct for batch effects, subsequently adjusting all gene expression profiles. Prior to this correction, the two cohorts were distinctly separate (Figure S1A). However, post-adjustment, they coalesced into a unified dataset (Figure S1B).

Deciphering central pathways in CcRCC patients

Utilizing the single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) via the “GSVA” software, we meticulously assessed 50 quintessential HALLMARK gene sets for each patient to elucidate pivotal biological pathway activations. This rigorous analysis juxtaposed the activation dynamics of 50 tumor-associated trajectories with gene compilations sourced from MsigDB20. The Enrichment Score (ES) epitomizes the primary outcomes of the gene enrichment scrutiny. Within the hierarchical arrangement, gene sets with positive ES values ascend to prominence, while those with negative ES values reside at the lower echelons. The Normalized Enrichment Score (NES) stands as the paramount metric for evaluating gene set enrichment outcomes. Meanwhile, the False Discovery Rate (FDR), delineating the proportion of erroneous identifications in all discerned results, adheres to a stringent threshold of 0.05. To elucidate disparities in immune activation statuses, NES values across various cohorts were derived from gene sets underscored by immune and stromal characteristics, as inferred from prior research21.

Collection sex-hormone-associated pathways and identifying distinct sex-hormone subtypes

We focused on the different activation status of sex hormone associated pathways in different ccRCC patients, and aim to identify the inner connection between it and the molecular feature or prognosis of ccRCC. Therefore, we collected several sex hormones associated signaling pathways reported in the MsigDB project, including hallmark gene set, ontology gene sets, and reactome gene sets of human beings. The details of these pathways listed in Table S1.

The distanceMatrix function of “ClassDiscovery” package, with the preset parameters of “euclidean”, “ward.D” setting was applied to identify the most sex-hormone enriched and scarce subtypes.

Genomic pathway elucidation

Utilizing the ‘limma’ package in R, we meticulously identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Criteria for DEG extraction were defined by an absolute log2(fold-change) surpassing 0.6, coupled with an adjusted P-value falling beneath 0.05. For a comprehensive Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, we harnessed the capabilities of the ‘org.Hs.eg.db’ and ‘msigdbr’ packages. To delve deeper into gene functionality and intricate pathway enrichment, the ‘ClusterProfiler’ tool was invoked22. Additionally, we employed the single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) to meticulously examine the tumor infiltration dynamics of 28 distinct immunocytes, subsequently deriving an individualized infiltration score for each immunocyte subtype across every patient23. The genetic aberrations were gleaned from the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) using the “TCGAbiolinks” suite. A graphical representation of these mutations was subsequently rendered utilizing the “maftools” R package24.

Formulating the prognostic SHAG signature

We executed a univariate Cox regression to meticulously dissect prognostic genes across both TCGA-KIRC and GSE22541 datasets. Following this, a Venn diagram was adeptly curated to spotlight intersecting prognostic genes warranting deeper exploration. The sophisticated least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis, facilitated by the ‘glmnet’ package25, was pivotal in optimizing and streamlining all input variables. This led to the construction of a statistical paradigm renowned for its unparalleled predictive acuity and elucidative prowess. LASSO, a distinguished regularization approach, proficiently circumvents overfitting, enhances feature selection prowess, and refines the regression model’s architecture with a finesse surpassing conventional ordinary least squares subset selection methodologies. This modus operandi is especially germane when confronted with a plethora of potential predictors, albeit with a mere subset anticipated to bear significance. In our study, we selected lambda.min, which is the value of lambda that results in the lowest cross-validation error. Genes discerned through LASSO analysis were integral in computing each patient’s risk quotient. This amalgamated gene expression metrics with coefficients to craft a quintessential sex-hormone-associated-gene (SHAG) prognostic marker. The formula is articulated as:

Here, \(\:{X}_{i}\) signifies the coefficient attributed to a gene, while \(\:{B}_{i}\) delineates the expression magnitude of the pertinent gene.

Establishment of a predictive nomogram

The prognostic prowess of the SHAG score across each dataset was rigorously evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier (K-M) plot and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Additionally, a multivariate Cox regression analysis was judiciously carried out to mitigate the influences introduced by other clinical variables, with findings elegantly illustrated within a forest plot. To further refine our diagnostic tools, we harnessed the capabilities of the “regplot” software, culminating in the formulation of a clinical prognostic nomogram. Variables emerging as salient from the multivariate Cox regression analysis were seamlessly integrated into the nomogram’s design. To ensure the nomogram’s clinical reliability and precision, we embarked on a series of evaluations, leveraging calibration curves, decision curve analysis, and clinical impact curve assessments. This meticulous verification process was facilitated by the “rms” and “rmda” toolkits.

Immunohistochemistry validation

To confirm the correlation between ARHGEF17 expression and the pathological stages of ccRCC, we employed an immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay to assess the protein expression levels of the aforementioned genes in a ccRCC tissue array obtained from Outdo Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). IHC staining was performed using ARHGEF17 antibodies (Cat. #: BD-PT3494, Biodragon LTD., Suzhou, China) at a dilution of 1:300.

Statistical analysis

To discern disparities between subgroups characterized by continuous variables, we deployed either the T-test or the Mann-Whitney U test. The Kaplan-Meier technique was instrumental in illustrating survival trajectories, with the log-rank methodology further validating these findings. In Chap. 5 “Assessing the Fit of the Model” of “Applied Logistic Regression”, it emphasized that “there is no “magic” number, only general guidelines”. Therein, the following values are given: ROC = 0.5 This suggests no discrimination; 0.5 < ROC < 0.7 We consider this poor discrimination; 0.7 ≤ ROC < 0.8 We consider this acceptable discrimination; 0.8 ≤ ROC < 0.9 We consider this excellent discrimination; ROC ≥ 0.9 We consider this outstanding discrimination26. Through a univariate Cox regression framework, we determined hazard ratios (HR) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for prospective genes. To evaluate the autonomous prognostic influence of the SHAG score, we engaged in multivariate Cox analyses, post-adjustment for an array of clinical determinants. Adhering to a significance benchmark of P < 0.05, our statistical evaluations were two-tailed in nature. All analytical endeavors were facilitated using the R software platform (version 4.2.2).

Results

Sex hormone-related signaling pathways exert a protective role in the prognosis of CcRCC patients

To ascertain the signaling pathways most intimately linked with tumor prognosis in ccRCC, we initially employed the GSVA technique. Upon assessing the activation levels of 50 hallmark tumor signaling pathways across all TCGA-KIRC patients, a comparative analysis was executed between those who succumbed to the disease and those who survived. Remarkably, among the deceased patients, there was a pronounced activation of pathways related to the cell cycle and gene repair, including G2M_CHECKPOINT, DNA_REPAIR, MYC_TARGETS_V1, and E2 F_TARGETS. Conversely, among surviving patients, there was evident activation of hormone-related pathways such as ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_EARLY and ANDROGEN_RESPONSE, in addition to immune response pathways like TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB, NOTCH_SIGNALING, and IL2_STAT5_SIGNALING (Fig. 1A).

Molecular landscape and clinical relevance of sex hormone signaling in ccRCC patients. (A) GSVA analysis of 50 hallmark tumor signaling pathways in TCGA-KIRC patients; (B) Unsupervised clustering based on the activation scores of 21 curated signaling pathways related to estrogen and androgen action; (C) Volcano plot presenting the differential gene expression between C1 and C3 subtypes; (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the three subtypes.

Proceeding with our investigation, we meticulously curated 21 signaling pathways from the GO and REACTOME databases that reflect the activation levels of estrogen and androgen. By leveraging the ssGSEA approach, each pathway was scored. Employing unsupervised cluster analysis based on these activation levels, patients were segregated into three subtypes (Fig. 1B). Patients of subtype C1 exhibited pronounced activation of pathways related to sex hormone action, encompassing gene expression, transcription, and intra- and inter-cellular signal transduction. The C3 subtype manifested strong activation in pathways concerning sex hormone metabolism and biosynthetic. Meanwhile, the C2 subtype demonstrated a moderate activation level across all pathways. Evaluating the prognosis of these subtypes, we discerned that subtype C1 patients had the most favorable outcomes, while C3 patients fared the worst (P = 0.00029, Fig. 1D).

Identification of pivotal genes linked to CcRCC prognosis concerning sex hormones

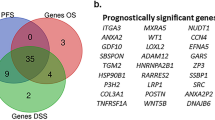

Our subsequent research delved into the differential gene expression between C1 and C3 subtypes. We identified 1,094 genes significantly upregulated in the C1 subtype, and 197 genes markedly elevated in the C3 subtype (Fig. 1C). These genes were predominantly involved in extracellular matrix regulation, endothelial cell differentiation, and GTPase activation (Figure S2). Utilizing univariate cox regression analysis across both TCGA-KIRC and GSE22541 cohorts, we pinpointed genes that either posed risks or conferred protective effects on the prognosis of ccRCC patients (Fig. 2A-B). By intersecting prognostic genes from both cohorts, we ultimately unveiled 20 risk-associated genes and 172 protective genes pertaining to ccRCC prognosis (Fig. 2C). The expression profile of these 192 genes across individual patients is depicted in Fig. 2D (for the TCGA-KIRC cohort) and Fig. 2E (for the GSE22541 cohort).

Prognostic gene identification and expression profiling in ccRCC cohorts. (A) Univariate Cox regression analysis of the TCGA-KIRC cohort highlighting genes with prognostic value. (B) Univariate Cox regression analysis for the GSE22541 cohort. (C) Venn diagrams displaying the overlap of risk-associated genes (upper diagram) and protective genes (lower diagram) between the TCGA-KIRC and GSE22541 cohorts. (D) Expression heatmap of the 192 intersected prognostic genes in the TCGA-KIRC cohort. (E) Expression heatmap of the 192 intersected prognostic genes in the GSE22541 cohort.

LASSO regression analysis identifies genes most reflective of CcRCC patient prognosis

We incorporated the 192 selected genes into a LASSO Cox regression analysis (Fig. 3A-B). Using a predetermined optimal lambda value 0.026, 33 genes and their respective coefficients were finalized for the model. Subsequently, we computed the SHAG scores for 528 patients in the TCGA-KIRC cohort (Fig. 3C), visualizing the relationship between SHAG scores and overall survival (OS), as well as the expression distribution of the 33 genes. Simultaneously, SHAG scores for 40 patients in the GSE22541 cohort were calculated (Fig. 3D), highlighting their association with OS and the expression distribution of the 33 genes within each patient.

LASSO Cox regression analysis and construction of SHAG prognostic model. (A) LASSO coefficient profiles of the 192 selected genes. Each curve corresponds to a gene, and the plot showcases changes in coefficients as the penalty parameter lambda increases on a log scale. (B) Plot of partial likelihood deviance against the log scale of lambda, highlighting the optimal lambda value (0.026) for model selection, indicated by the vertical dotted line. (C) Risk map showing the SHAG score for each patient and distribution of overall survival time in TCGA-KIRC cohort, with the heatmap illustrating the expression profiles of the 33 prognostic genes across patients. (D) Risk map showing the SHAG score for each patient and distribution of overall survival time in GSE22541 cohort, with the heatmap illustrating the expression profiles of the 33 prognostic genes across patients.

Cause the prognostic value of ARHGEF17 is less validated in real-world sample. We used ccRCC tissue samples to validate the protein level of ARHGEF17 with IHC staining. We present the 8 represantative results, and showing that ARHGEF17 protein displayed a higher level in stage I-II samples, as compared to stage III samples. And we also observed that the ARHGEF17 protein most presented in cytosol (Fig. 4).

SHAG risk score differentiates CcRCC patient prognosis

Within the TCGA-KIRC cohort, based on the median of SHAG scores, patients were divided into two groups: high-SHAG and low-SHAG score groups. We observed that patients in the high-SHAG score group had a significantly worse prognosis compared to those in the low-SHAG score group (HR = 3.26, 95% CI: 2.334–4.555, P < 0.001, Fig. 5A). Furthermore, employing ROC curves to evaluate the model’s predictive capabilities, the model’s AUC was 0.768 at 1 year, 0.747 at 3 years, and 0.751 at 5 years (Fig. 5B), indicating its robust prognostic value. Additionally, the model’s predictive ability was compared against other clinical parameters, revealing superior prognostic prediction. When combined with other clinical markers to form a new model, its predictive power improved to an AUC of 0.836 (95% CI: 0.793–0.879, Fig. 5C). We further assessed the variance in SHAG scores across different tumor stages, discovering that as tumor staging increased, so did the SHAG scores (P < 0.001, Fig. 5D). This trend was consistent across different tumor grades (P < 0.001, Fig. 5E). In the GSE22541 cohort, after grouping patients based on the median of SHAG scores, it was observed that those with high-SHAG score had poorer prognosis (HR = 3.22, 95% CI: 1.549–6.693, P = 0.002, Fig. 5F). In this cohort, the model’s AUC was 0.791 at 1 year, 0.801 at 3 years, and 0.858 at 5 years (Fig. 5G). Moreover, the newly developed model displayed enhanced prognostic prediction capabilities over metrics like tumor type and gender (Fig. 5H).

Prognostic value and prediction performance of the SHAG model in TCGA-KIRC and GSE22541 cohorts. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of the TCGA-KIRC cohort. (B) Time-dependent ROC curves of the SHAG score model for 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival prediction in the TCGA-KIRC cohort. (C) Comparison of the prognostic accuracy between the SHAG score model and other clinical parameters in the TCGA-KIRC cohort. (D) Box plot showing the distribution of SHAG scores across different tumor stages in the TCGA-KIRC cohort. (E) Distribution of SHAG scores across various tumor grades in the TCGA-KIRC cohort. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for the GSE22541 cohort. (G) Time-dependent ROC curves of the SHAG score model for 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival prediction in the GSE22541 cohort. (H) Prognostic accuracy comparison of the SHAG score model against other parameters in the GSE22541 cohort.

Investigating differentially activated signaling pathways and genetic alterations between patients with high and low SHAG score in CcRCC

To provide a more comprehensive assessment of the disparities between patients with high and low SHAG scores during the tumorigenesis process of ccRCC, we initially evaluated the differences in pathway activation between these two groups. In high-SHAG score patients, several pathways were significantly upregulated, including INTERFERON_ALPHA_RESPONSE, INTERFERON_GAMMA_RESPONSE, TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB, P53_PATHWAY, ALLOGRAFT_REJECTION, IL6_JAK_STAT3_SIGNALING, INFLAMMATORY_RESPONSE, G2M_CHECKPOINT, and E2 F_TARGETS. In contrast, in low-SHAG score patients, alternative pathways such as ANDROGEN_RESPONSE, MITOTIC_SPINDLE, TGF_BETA_SIGNALING, UV_RESPONSE_DN, NOTCH_SIGNALING, WNT_BETA_CATENIN_SIGNALING, and HEDGEHOG_SIGNALING were more prominently activated (Fig. 6A). Concurrently, we further analyzed the infiltration of immune cells and found that high-SHAG score patients exhibited more extensive immune cell infiltration, predominantly consisting of various T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, and macrophages (Fig. 6B).

Disparities in pathway activation and immune cell infiltration between high and low-SHAG score patients in ccRCC. (A) Heatmap displaying the differential pathway activation between low- and high-SHAG score patients. (B) Heatmap illustrating the differences in immune cell infiltration between the two patient groups.

Moreover, we compared the genetic alterations between the two groups. We discerned a notably higher tumoral mutation burden in the high-SHAG score cohort (P = 0.012, Fig. 7A), potentially correlated with copy number variations. High-SHAG score patients manifested more extensive copy number alterations, whether genome loss or gain (P < 0.0001, Fig. 7B). Delving deeper into specific gene mutations, low-SHAG score patients exhibited a higher frequency of PBRM1 gene mutations (47.3% vs. 30.6%, P = 0.00124, Fig. 7C, Table S2), whereas the high-SHAG score group was characterized by more mutations in SETD2, BAP1, MUC16, and KDM5 C (Fig. 7C, Table S2). Additionally, we evaluated differentially expressed genes between patients with and without genomic alterations (Fig. 7D), noting a significant upregulation of the SCGN gene in patients with genomic alterations (P < 0.001, Fig. 7E). Elevated SCGN gene expression correlates with a favorable prognosis (HR = 0.52, P < 0.001, Fig. 7F), establishing SCGN as a protective prognostic factor for ccRCC patients.

Genetic alterations and their implications in low and high-SHAG score ccRCC patients. (A) Tumoral mutation burden comparison between low- and high-SHAG score patients. (B) Representation of the extent of copy number alterations in low- and high-SHAG score. (C) Mutation frequency of specific genes including PBRM1, SETD2, BAP1, MUC16, and KDM5 C. (D) Volcano plot highlighting differentially expressed genes between patients with genomic alterations and those without. (E) SCGN gene expression distribution between patients with and without genomic alterations. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curve elucidating the relationship between SCGN expression levels and overall survival.

Constructing a prognosis prediction nomogram based on independent risk factors

Subsequently, incorporating various clinical indicators in the TCGA-KIRC cohort, we conducted a multifactorial cox regression analysis. The findings illuminated age (HR = 1.031, 95% CI: 1.016–1.046, P < 0.001), tumor stage (Stage IV: HR = 2.389, 95% CI: 1.486–3.842, P < 0.001), tumor status (With tumor: HR = 2.633, 95% CI: 1.799–3.855, P < 0.001), and SHAG score as independent prognostic factors (HR = 2.574, 95% CI: 1.909–3.471, P < 0.001, Table 1). Based on this analysis, we established a prognostic nomogram incorporating these independent factors (Fig. 8A). Utilizing the nomogram, we computed points for all included patients, discovering a significant negative correlation between nomogram points and survival duration for deceased patients (R=− 0.27, P = 0.00043, Fig. 8B). Furthermore, deceased patients had notably higher average points than survivors (P < 0.001, Fig. 8C). We validated the predictive capability of the nomogram through calibration analysis, revealing its accurate reflection of actual outcomes when forecasting 1-year (Hosmer-Lemeshow P = 0.195, Fig. 8D), 3-year (Hosmer-Lemeshow P = 0.306, Fig. 8E), and 5-year prognoses (Hosmer-Lemeshow P = 0.193, Fig. 8F). Based on the calculated points, patients were bifurcated into high and low point groups. Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrated a markedly worse prognosis for the high-point group compared to the low-point group (HR = 5.280, 95% CI: 3.576–7.787, P < 0.001, Fig. 8G). The ROC curve further showcased the commendable predictive capacity of the nomogram (AUC: 1-year, 0.861; 3-year, 0.843; 5-year, 0.842, Fig. 8H). A DCA curve was performed, underscoring the high clinical net benefit of the nomogram model across almost the entire threshold probability compared to other features (Fig. 8I).

Prognostic assessment and validation of the established nomogram for predicting survival outcomes. (A) Prognostic nomogram integrating independent factors such as stage, age, tumor status, and genetic prognostic model. (B) Scatter plot displaying the significant negative correlation between nomogram-derived points and survival duration for deceased patients. (C) Box plot contrasting the average nomogram points between alive and deceased patients. (D-F) Calibration plots demonstrating the predictive accuracy of the nomogram for 1-year (D), 3-year (E), and 5-year (F) survival outcomes. (G) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients stratified into high and low point groups based on the nomogram. (H) Receiver operating characteristic curves for 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year predictions. (I) Decision curve analysis emphasizing the superior clinical net benefit of the nomogram model over a range of threshold probabilities in contrast to other individual features.

Discussion

The intricate and multivariate processes underlying cancer prognosis have long been a subject of investigation, especially in relation to ccRCC, given its unpredictable disease course27,28,29. RCC is fundamentally a metabolic disorder characterized by the reprogramming of energy metabolism30,31. It has been reported that the tyrosine kinase Abl2 facilitates the activation of the TGFβ1/Smad signaling pathway, thereby promoting ccRCC cell invasion and the maturation of invadopodium32. ccRCC cells expressing MUC1 exhibit distinct metabolic reprogramming features, and the suppression of MUC1 expression leads to decreased cell motility and viability while enhancing cisplatin sensitivity33. Additionally, NDUFA4L2 is highly expressed in renal cancer cells, and its silencing impairs cell viability, increases mitochondrial mass, and induces ROS generation under hypoxic conditions34.

In our comprehensive study, we delved deeply into the signaling pathways and their association with the prognosis of ccRCC patients. Our analysis, leveraging the GSVA technique, provided evidence that pathways associated with the cell cycle and gene repair are prominently activated in deceased patients. This aligns with prior studies emphasizing the involvement of these pathways in various cancers. Particularly, cell cycle regulation disruption is pivotal in tumor development35,36,37, and elevated DNA repair capacity can provide tumors resistance against genotoxic treatments38,39. In stark contrast, our data suggested a protective effect for hormone-related pathways, such as the ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_EARLY and ANDROGEN_RESPONSE. Interestingly, hormone pathways, especially those related to estrogen and androgen, have been implicated in various cancer types, with diverse roles. For instance, estrogen is known to promote breast cancer40, but it exhibits suppressive effects in colon cancer41,42. Our findings suggest a protective role of these pathways in ccRCC, which is an intriguing avenue for future investigations.

Through a systematic and meticulous analysis, our study stratified patients based on activation levels of hormone-related signaling pathways, enabling the identification of distinct patient subtypes. Intriguingly, those with pronounced activation of pathways pertinent to sex hormone action fared better in terms of prognosis. The identification of pivotal genes associated with ccRCC prognosis in the context of sex hormones further augmented the depth of our analysis. While a myriad of models has been proposed for predicting the prognosis of ccRCC, the incorporation of 192 pivotal genes in a LASSO regression model culminated in SHAG model that offers robust prognostic value. Intriguingly, some of these genes have previously been reported with roles in various cancers, cementing their importance in tumor biology. For instance, MMP9, a member of the matrix metalloproteinase family, has been recognized for its role in tissue remodeling and, in the context of cancer, in promoting metastasis43,44. Furthermore, NOTCH3 signaling has been implicated in RCC progression45. Conversely, genes such as ATP10D, which appeared as protective factor in our model, might serve as potential therapeutic targets to enhance the survival prospects of ccRCC patients.

Such a nuanced approach ensures that the derived risk score encapsulates the multifaceted genetic underpinnings of the disease. An essential aspect of our study was the examination of differences in pathway activation, immune cell infiltration, and genetic alterations between high and low SHAG score patients. High-SHAG score patients exhibited an amplified activation of inflammatory and immune response pathways. Such insights might pave the way for harnessing immunotherapies tailored to specific patient groups. Another pivotal finding was the establishment of the SCGN gene as a protective prognostic factor for ccRCC patients. Some studies have indicated that SCGN might be involved in processes that influence tumor progression. For example, the expression of SCGN correlates with an increased risk of suffering disease relapse after radical prostatectomy46.

Lastly, the prognostic nomogram developed in this study stands as an epitome of integrating various clinical indicators to furnish a holistic picture of patient prognosis. With its impressive predictive capability, this nomogram might soon find its way into clinical settings, aiding clinicians in tailoring therapies and counseling patients.

Despite the promising findings of this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the number of samples and cohorts included in the analysis is relatively limited, which may impact the generalizability of our conclusions. Although the TCGA-KIRC and GSE22541 cohorts provided valuable insights, larger and more diverse independent datasets are needed for further validation. Second, our model incorporates a relatively large number of genes, which may require an extensive sequencing panel for clinical application, potentially limiting its feasibility in routine clinical practice. Future studies should aim to refine the gene set while maintaining its predictive accuracy. Additionally, while we identified key pathways and prognostic markers, experimental validation in independent cohorts and functional studies are necessary to further confirm their biological significance and clinical utility.

Conclusion

In summary, our study elucidates the protective role of sex hormone signaling pathways in ccRCC prognosis. The identification of pivotal genes and the subsequent development of SHAG score formula offer a novel stratification tool, which, when combined with traditional clinical markers in our nomogram, presents a robust prognostic predictor. Our findings pave the way for further investigations into the therapeutic targeting of these pathways and genes, potentially altering the therapeutic landscape of ccRCC.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study can be found in the GEO database, and TCGA database. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/Changbaoyuan/SHAG).

References

Cairns, P. Renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 9 (1–6), 461–473 (2010).

Zi, H. et al. Global burden of benign prostatic hyperplasia, urinary tract infections, urolithiasis, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, and prostate cancer from 1990 to 2021. Mil Med. Res. 11 (1), 64 (2024).

Siegel, R. L., Kratzer, T. B., Giaquinto, A. N., Sung, H. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 75 (1), 10–45 (2025).

Ogawa, O. et al. Allelic loss at chromosome 3p characterizes clear cell phenotype of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 51 (3), 949–953 (1991).

Gossage, L., Eisen, T. & Maher, E. R. VHL, the story of a tumour suppressor gene. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 15 (1), 55–64 (2015).

Alchahin, A. M. et al. A transcriptional metastatic signature predicts survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 5747 (2022).

Yamana, K., Ohashi, R. & Tomita, Y. Contemporary drug therapy for renal cell Carcinoma- evidence accumulation and histological implications in treatment strategy. Biomedicines 10(11), 2804 (2022).

Vuong, L., Kotecha, R. R., Voss, M. H. & Hakimi, A. A. Tumor microenvironment dynamics in Clear-Cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 9 (10), 1349–1357 (2019).

Lasorsa, F. et al. Cellular and molecular players in the tumor microenvironment of renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 12(12), 3888 (2023).

Tamma, R. et al. Microvascular density, macrophages, and mast cells in human clear cell renal carcinoma with and without bevacizumab treatment. Urol Oncol 37(6):355 e311-355 e319. (2019).

Meng, J. et al. Multiomics characterization and verification of clear cell renal cell carcinoma molecular subtypes to guide precise chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Imeta 2 (4), e147 (2023).

Lucarelli, G. et al. Activation of the kynurenine pathway predicts poor outcome in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urol. Oncol. 35 (7), 461e415–461e427 (2017).

Ragone, R. et al. Renal cell carcinoma: A study through NMR-Based metabolomics combined with transcriptomics. Diseases 4(1), 7 (2016).

Rini, B. I., Campbell, S. C. & Escudier, B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet 373 (9669), 1119–1132 (2009).

Tao, C. et al. PAQR5 expression is suppressed by TGFbeta1 and associated with a poor survival outcome in renal clear cell carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 11, 827344 (2021).

Wang, K., Sun, Y., Tao, W., Fei, X. & Chang, C. Androgen receptor (AR) promotes clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) migration and invasion via altering the circHIAT1/miR-195-5p/29a-3p/29c-3p/CDC42 signals. Cancer Lett. 394, 1–12 (2017).

Zhao, H., Leppert, J. T. & Peehl, D. M. A protective role for androgen receptor in clear cell renal cell carcinoma based on mining TCGA data. PLoS One. 11 (1), e0146505 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Estrogen receptor beta increases clear cell renal cell carcinoma stem cell phenotype via altering the circPHACTR4/miR-34b-5p/c-Myc signaling. FASEB J. 36 (2), e22163 (2022).

Han, Z. et al. ERbeta-Mediated alteration of circATP2B1 and miR-204-3p signaling promotes invasion of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 78 (10), 2550–2563 (2018).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102 (43), 15545–15550 (2005).

Meng, J. et al. Tumor immune microenvironment-based classifications of bladder cancer for enhancing the response rate of immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 20, 410–421 (2021).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics 16 (5), 284–287 (2012).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612 (2013).

Mayakonda, A., Lin, D. C., Assenov, Y., Plass, C. & Koeffler, H. P. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28 (11), 1747–1756 (2018).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33 (1), 1–22 (2010).

Hosmer, D. W. Jr, Lemeshow, S. & Sturdivant, R. X. Applied Logistic Regression (Wiley, 2013).

Nyman, J. et al. Spatially aware deep learning reveals tumor heterogeneity patterns that encode distinct kidney cancer States. Cell. Rep. Med. 4 (9), 101189 (2023).

Ye, S. et al. Protein arginine methyltransferases refine the classification of clear cell renal cell carcinoma with distinct prognosis and tumor microenvironment characteristics. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 19 (14), 4552–4570 (2023).

Dizman, N., Philip, E. J. & Pal, S. K. Genomic profiling in renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16 (8), 435–451 (2020).

Lucarelli, G. et al. Metabolomic insights into pathophysiological mechanisms and biomarker discovery in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 19 (5), 397–407 (2019).

di Meo, N. A. et al. Renal cell carcinoma as a metabolic disease: an update on main pathways, potential biomarkers, and therapeutic targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(22), 14360 (2022).

De Marco, S. et al. The cross-talk between Abl2 tyrosine kinase and TGFbeta1 signalling modulates the invasion of clear cell renal cell carcinoma cells. FEBS Lett. 597 (8), 1098–1113 (2023).

Lucarelli, G. et al. MUC1 tissue expression and its soluble form CA15-3 identify a clear cell renal cell carcinoma with distinct metabolic profile and poor clinical outcome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(22), 13968 (2022).

Lucarelli, G. et al. Integrated multi-omics characterization reveals a distinctive metabolic signature and the role of NDUFA4L2 in promoting angiogenesis, chemoresistance, and mitochondrial dysfunction in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 10 (12), 3957–3985 (2018).

Wang, W., Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Xu, Y. & Zhang, S. Identifies microtubule-binding protein CSPP1 as a novel cancer biomarker associated with ferroptosis and tumor microenvironment. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 3322–3335 (2022).

Wu, Y. et al. RCC1 functions as a tumor facilitator in clear cell renal cell carcinoma by dysregulating cell cycle, apoptosis, and EZH2 stability. Cancer Med. 12(19), 19889–19903 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. TROAP promotes the proliferation, migration, and metastasis of kidney renal clear cell carcinoma with the help of STAT3. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(11), 9658 (2023).

Chabanon, R. M. et al. PBRM1 deficiency confers synthetic lethality to DNA repair inhibitors in cancer. Cancer Res. 81 (11), 2888–2902 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. The deubiquitinase USP38 promotes NHEJ repair through regulation of HDAC1 activity and regulates cancer cell response to genotoxic insults. Cancer Res. 80 (4), 719–731 (2020).

Turrell, F. K. et al. Age-associated microenvironmental changes highlight the role of PDGF-C in ER(+) breast cancer metastatic relapse. Nat. Cancer. 4 (4), 468–484 (2023).

Hases, L. et al. Intestinal Estrogen receptor beta suppresses colon inflammation and tumorigenesis in both sexes. Cancer Lett. 492, 54–62 (2020).

Kim, N., Kwon, J., Shin, U. S. & Jung, J. Stimulatory anticancer effect of Resveratrol mediated by G Protein-Coupled Estrogen receptor in colorectal cancer. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 31(6), 655–660 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. G6PD upregulates Cyclin E1 and MMP9 to promote clear cell renal cell carcinoma progression. Int. J. Med. Sci. 19 (1), 47–64 (2022).

Gong, D. et al. The m(6)A-suppressed P2RX6 activation promotes renal cancer cells migration and invasion through ATP-induced Ca(2+) influx modulating ERK1/2 phosphorylation and MMP9 signaling pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38 (1), 233 (2019).

Han, Q. et al. Notch3 is involved in the proliferation of renal cancer cells via regulation of cell cycle progression and HIF-2alpha. Oncol. Lett. 20 (6), 379 (2020).

Flores-Morales, A. et al. Proteogenomic characterization of Patient-Derived xenografts highlights the role of REST in neuroendocrine differentiation of Castration-Resistant prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 25 (2), 595–608 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by Anhui Medical University Youth Science Fund Project (2023xkj071); Scientific research project of Suzhou Municipal Health Commission (SZWJ2023a011); Scientific research project of Suzhou Science and Technology Bureau (SZZCZJ202326).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GXY and SJH was responsible for data processing and wrote the manuscript, prepared tables and figures. SJH, DY and LZW analyzed the data. GXY, MSM and ZS performed statistical analyses. ZZY, SK, ZDB, JT and CBY contributed to study design, editing, directed the writing of the article and put forward suggestions. All authors contributed to the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geng, X., Shan, J., Dai, Y. et al. Regulatory mechanism and prognostic value of sex hormone pathways connected with metabolism and immune signaling in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 13482 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97163-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97163-4