Abstract

Real-world scenarios are inherently dynamic and open-ended, necessitating that current deep models adapt to general objects in open realities to be practically useful. In this paper, we extend a valuable computer vision task called General Object Search in Open Reality (GOSO). The main objective of GOSO is to determine whether an object from the open world appears in another gallery image, even when composed of arbitrary entities and backgrounds. However, two significant challenges arise: the high scale variance among different instances of the same entity and the vast openness with an ever-expanding set of unknown categories in the open world. To address these issues, we formalize the GOSO problem and propose a simple yet effective architecture named Siamese Exchanged Attention Network (SEA-Net). Specifically, based on a standard siamese structure, SEA-Net introduces a novel branch that comprises multiple stage-stacked Siamese Exchanged Attention (SEA) layers followed by a Hierarchical Feature Fusion (HFF) module, enabling efficient scale adaptation and the extraction of matching-friendly deep features. Moreover, an Open Score Fusion (OSF) module is integrated into SEA-Net during inference to yield a more robust matching score in open-world scenarios. We construct two new evaluation benchmarks suitable for the GOSO task using the existing COCO and LVIS datasets, and extensive experiments consistently demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Humans exhibit a powerful ability to search for designated targets in the open world. That is, given a query of dog, regardless of whether this class has been seen before or not, even a child can easily determine whether other images contain its objects. This kind of ability is innate to humans, yet it is hard to reach deep networks. Moreover, with the exponential increase in the amount of data, object search is becoming one of the most essential techniques for many downstream vision tasks, such as auto-labeling and so on.

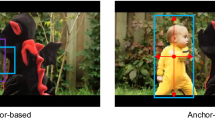

Lately, some related topics have been explored in depth, such as image retrieval and matching1, but most of them work under the setting of specific scenes or entities, e.g., pedestrians2, vehicle3, products4 and buildings1, which is still far from satisfactory for many real needs. It is of thus motivating us to extend a valuable vision task called General Object Search in Open Reality (GOSO), where a deep model is tasked to identify whether an object query from the open world appears in another complicated image with arbitrary entities and background or not. Consider the Fig.1, there are two main challenges in this task: (1) high scale-variance, the object scales of the same category in different gallery images vary greatly, leading to the inability to align between local and global features, and (2) large entity-openness, the category range in the open scenario is progressively expanding, i.e., a coming query may contain objects from unknown space, and it should still be discovered aright even if the model is not updated anymore.

Prior to this, the matter of scale-variance has been widely studied in object detection, which often employs the region-of-interest (RoI) pooling to align multi-scale features5. Unlike these current detection pipelines with equipping RoI or localization branch, GOSO only focuses on the question of whether or not without any box priors, which is achieved through feature-level matching with lower complexity. Besides, although the multi-label classification task6 can judge which categories are contained in a picture, it only works in the closed setting with seen classes, which greatly limits its application scenarios in open reality. In fact, we argue that openness is one of the criteria for measuring the ability of a task to adapt to open world. In spite of some subtasks of image retrieval, which are formalized as a matching problem, have weak openness in certain specific fields, their paradigms of patch-to-patch (instance-level) or image-to-image (pixel-wise) yet increase the difficulty of directly adapting to general object search. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 2, due to the high scale-variance, large openness and category-level searching, the GOSO is still under-explored.

In this work, we propose a simple yet effective approach, named Siamese Exchanged Attention Network (SEA-Net), to deal with the essential challenges in GOSO. The overall architecture of SEA-Net is very straightforward as demonstrated in Fig. 3. Compared with the standard siamese structure, SEA-Net additionally adopts another attention branch to perform rich feature interaction and flexible scale adaptation between the query and gallery across multiple stages. From the perspective of intra- and inter-stage, the newly inserted branch consists of two novel modules, i.e., Siamese Exchanged Attention layer (SEA) and Hierarchical Feature Fusion module (HFF). The former is a symmetric structure that takes the query feature and gallery feature of the other two branches as inputs, see the right part of Fig. 3. Based on the attention mechanism, on the one hand, information interaction is conducted by exchanging query matrices between two inner-branches of SEA layer, and on the other hand, the fusion feature with stronger semantics is obtained by performing mutual response on the attention map. The latter one is a weighted summation operator for integrating the output features from multiple stages. Since hierarchical blocks have gradually-scaled receptive fields from low- to high-level, the HFF helps to extract features with richer semantics. However, under the setting of GOSO, the above branch can only be optimized on known classes, which is far less than unknown data in open reality. In order to narrow the inductive bias on seen spaces, SEA-Net further employs an Open Score Fusion module (OSF) to produce robust scores for queries from know and unknown spaces.

The main contributions of our approach are four-folds:

-

To tackle the matter of whether or not, we formally extend a valuable and practical vision task, named GOSO, which models the real world more closely.

-

We propose a simple yet effective architecture for GOSO, called SEA-Net, which consists of multiple stage-stacked SEA layers, a following HFF module and a cost-free OSF strategy, to address the challenges of GOSO task.

-

We curate two large GOSO datasets from existing detection datasets, i.e., COCO and LVIS. We set up benchmarks for comprehensive GOSO performance evaluation.

-

Extensive experiments on these benchmarks consistently demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed method.

The architecture of Siamese Exchanged Attention Network (SEA-Net) for General Object Search in Open Reality (GOSO). The model is composed of three parallel branches, two of which share weights and are used to extract the features of gallery and query respectively, termed as G-branch (blue) and Q-branch (green). The other branch (orange) progressively extracts the desirable features with richer semantic information through multiple stage-stacked SEA layers. Then these features are fused by the Hierarchical Feature Fusion module (HFF), which is concretized as a weighted summation function (\(\Sigma\)) in Section “Siamese exchanged attention module”. Note that \({W}_{Q}\), \({W}_{K}\), \({W}_{V}\) are shared by G-branch and Q-branch in each SEA layer. Finally, the features from all three branches are fed into a shared classification layer C (yellow) to calculate loss value (during training) or the proposed Open Score Fusion module (OSF) in Section “Open score fusion module” to produce matching scores (during inference).

Related works

Content-based image retrieval

Content-based Image Retrieval searches for semantically similar pictures in a large gallery by analyzing their visual content with a query. It is generally divided into two groups:

Instance-level image retrieval

Given a query image of a particular object, this task aims at finding images containing the same instance that may be captured under different conditions. With the rise of deep models, most of the recent progresses in this field are based on CNNs. For example, re-identification (ReID) retrieves a query-of-interest across multiple non-overlapping cameras, where the instance can be pedestrian7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 or vehicle3,15,16. In addition, clothing retrieval17 is also a similar research topic. No matter which one of the above tasks, their query and gallery usually appear in the form of cropped patches, that is, there is no complicated background. However, the gallery image in GOSO usually contains more entities and complex scenes, which greatly increases the difficulty of object retrieval. One of the most related to GOSO is person search18,19,20, which is usually regarded as an extension of the person ReID with an additional detector in the scenes. Note GOSO extends the entity category from pedestrian to arbitrary objects and solves the problem end-to-end.

Category-level image retrieval

The goal of this task is to retrieve images including the same category as the query, which focuses more on coarse-grained information than instance-level.21 proposes a bidirectional approach to rank for representation learning and22 deploys the multiple labels to learn the semantic space. Moreover,23 looks into the effectiveness of classification-based approaches on image retrieval tasks and4 introduces a cooperative embedding to integrate category-level and instance-level while preserving their specific level of semantic representation. Instead of evaluating on the fine-grained and closed datasets, such as Cars-19624, CUB20025 and Product26, the GOSO task shares the same vision with category-level retrieval but focuses more on open scenario.

Image matching

Image matching is a vision task of identifying then corresponding the similar structure from two images1, which generally maintains at the pixel-wise and instance-level correspondence. In particular, the deep feature-based image matching pipeline, which is composed of feature detection, description and then matching sequentially, has been flexibly adopted into 3d-reconstruction27,28, VSLAM29,30 and image retrieval31,32,33. Due to the image similarity being intrinsically determined by the feature matches between images, the retrieval score can be obtained by aggregating votes from the matched features. Recent advances in re-identification further push the boundaries of image matching. For example,34 proposes a novel dual-domain modulation framework that mitigates the domain gap between daytime and nighttime vehicle images by incorporating a glare suppression module, a dual-domain structure enhancement module, and a cross-domain class awareness module. These components help obtain more robust features for cross-domain matching. Similarly,35 leverages high-order structural information to learn middle-level features that are effective for matching visible and infrared images. Moreover,36 provides a comprehensive review of Transformer-based approaches that, by exploiting both global and local feature correspondences, enhance the robustness of image matching in object re-identification tasks. However, unlike retrieval based on image matching, where the images for matching are taken from the same or similar object while captured at different times or viewpoints, GOSO is set to retrieve based on high-level semantics, not pixel-by-pixel.

Multi-label classification

This task aims to gain a comprehensive understanding of image and then identify all known entities in it accordingly. There are three main research branches: (1) improving the loss function from the perspective of imbalance data37,38,39, (2) mining label correlations from the view of knowledge transfer40,41 and (3) digging out more reasonable regions of activation response42,43,44. Due to the closed nature of this topic6, all above approaches can only identify known categories, while ignoring meaningful classes of unseen entities. Yet, GOSO is essentially a matching problem, that is, to determine whether a picture contains a certain category, including unknown entities.

Open-world applications

Due to the inductive-bias of deep networks, the performance of most existing approaches on many vision tasks will be severely degraded in open-world scenarios.45,46,47 and48 identify unknown classes in classification and detection problems through softmax-variant and contrastive-clustering, respectively. Moreover, some few-shot methods further explore feature adaptation on novel domain49 with very few annotated data, such as model-finetuing50,51,52 and feature-attention53. As for the category-level retrieval, our SEA-Net focus on the multi-scale feature matching, as well as the adaptation on query-shot.

General object search in open reality

To define the problem of GOSO formally, we assume that there are two disjoint datasets \({D}_{K}\) and \({D}_{U}\) in real world, with known classes \({C}_{K} = \{1, \dots , C \}\) and unknown classes \({C}_{U} = \{C+1, \dots \}\) respectively, where C is the number of annotated categories and \({C}_{U}\) can only be encountered during inference. Hereafter, let us first consider the training set \({D}_{tr}\) with consisting of a query set \({D}^{Q}_{tr} = \{x_q, y_q\}\) and a gallery set \({D}^{G}_{tr} = \{ x_g, \vec {y}_g\}\), i.e., \({D}_{tr} = \{ {D}^{Q}_{tr}, {D}^{G}_{tr} \}\), where \(x_q\) is an object patch (cropped image without background) and \(y_q \in {C}_{K}\) is its label, \(x_g\) is an image from the open reality and \(\vec {y}_g = \{y_i\}_{i=1}^{N}\) is annotated by a label vector, where \(y_i \in \{0, 1\}\) denotes whether the class i is present in the image (‘1’) or absent (‘0’). As for the testing set \({D}_{te} = \{ {D}^{Q}_{te}, {D}^{G}_{te} \}\), in order to realistically model the dynamics of open world, we further introduce unknown entities into both query set \({D}^{Q}_{te} = \{x_q, y_q\}\) and gallery set \({D}^{G}_{te} = \{ x_g, \vec {y}_g\}\), where \(y_q \in {C}_{K} \cup {C}_{U}\) and \(\vec {y}_g = \{y_i\}_{i=1}^{N+\mid {C}_{U} \mid }\).

Under this setting, the ultimate goal of our algorithm is to optimize a robust feature extractor F based on the known dataset \({D}_{tr}\) and then, given a query \(q_{i}\) from \({D}_{te}^{Q}\) (one-shot), the trained model calculates the matching probability \(p_{i}\) between the query and a gallery image \(g_i\) from \({D}_{te}^{G}\), i.e.,, \(p_{i} \leftarrow {F}(q_{i}, g_{i})\). Due to the limited number of seen classes during the training procedure, matching unknown queries correctly requires the model to have strong generalization and adaptability. In addition, in open reality, different objects of the same category, or even the same object while captured at different times or from different viewpoints, are inconsistent in scale. Thus, a scale-insensitive and efficient content-to-content matching module is desirable to establish appropriate correspondences.

As shown in Fig. 2, GOSO is fundamentally a cross-image matching task. Unlike multi-label open-set recognition-which classifies every object within a single image and rejects unknown categories based on global features-GOSO focuses on verifying whether a query object appears in a gallery image using fine-grained content matching.

Methodology

This section first provides an overview of the SEA-Net architecture and then elaborates on the Siamese Exchanged Attention module (SEA) to learn a general embedding containing semantic and matching representation, which takes intra- and inter-stage scale adaptation into consideration. Next, the Open Score Fusion (OSF) module is proposed to improve the robustness of matching scores in open reality.

Architecture overview

Figure 3 shows the high-level architectural overview of our method. To be concrete, given a pair of query image \({I}_q\) and gallery image \({I}_g\), a weights-shared backbone is first employed to extract the deep features \(x^k_q\) and \(x^k_g\) for query and gallery respectively, where k represents the k-th stage of backbone. Then the features \(x^k_q\) and \(x^k_g\) from the same stage are fed into the novel Siamese Exchanged Attention layer (SEA), which is illustrated in the Fig. 3 (right) in details (see Section “Siamese exchanged attention module”), to perform dense content-to-content matching on feature-level by attention activation. Furthermore, since different stages have gradually-scaled receptive fields, the following Hierarchical Feature Fusion module (HFF) summarizes the SEA features for richer semantics, \(\Sigma\) in Fig. 3, which further alleviates the problem of high scale-variance under the setting of GOSO. During training, all these features from three branches are fed into a shared classification layer C for predicting labels. With optimizing on the known dataset \({D}^{tr}_{K}\), the overall loss function can be formalized as,

where \(\theta _b\) , \(\theta _s\) and \(\theta _{c}\) are the parameters of the siamese backbone, the SEA module and the classifier respectively. Note the \(\theta _b\) is frozen during finetuning and we choose cross-entropy loss as the supervised function. In inference, the forward pipeline removes the last classifier and then uses the Open Score Fusion module to produce matching scores.

Siamese exchanged attention module

Attention mechanisms aim to highlight important local regions and extract more discriminative features. Yet, on the one hand, due to learning only on the closed priors of known classes, the conventional attention structure cannot be well generalized to unknown spaces. On the other hand, it is high-complexity to establish a dense region-to-region matching relationship between the separated feature maps from the query branch (Q-branch) and gallery branch (G-branch), resulting in poor adaptability to the object scale. In this section, we first revisit the existing structure of All-Attention Fusion (AAF)54 and analyze its shortcomings, and then propose a novel Siamese Exchanged Attention module (SEA) with the symmetrical structure to model the semantic relevance between the gallery and query features, \({i.e. },\), \(x^k_g\) and \(x^k_q\), thus draw scale-insensitive attention to the target objects and benefit the subsequent matching.

Revisiting all-attention fusion

As one of the most straightforward approaches for feature interaction, All-Attention Fusion (AAF) simply concatenates all features from the query and gallery branches and then integrates the information via a standard self-attention module55. This module comprises a multi-head attention mechanism followed by a feed-forward network, with layer normalization (LN) applied prior to each block. In our implementation, given an input feature matrix \(x_f^k\), the multi-head attention mechanism first projects it into query (Q), key (K), and value (V) matrices using learnable linear transformations. These matrices are then divided into h independent heads:

where each head operates in a subspace of dimension \(d_k = \frac{d}{h}\) (with d being the original feature dimension). For each head i, the attention output is computed as:

The outputs from all heads are then concatenated and passed through an additional linear projection to form the final output of the multi-head attention block. In our formulation, this entire multi-head attention process is denoted by \({AAF}^{\dagger }(\cdot )\) in Equation (2). However, due to a lack of branch-specific consideration, this scheme incurs a quadratic computational cost relative to the number of features. The output \(z^k\) of AAF can be expressed as:

where \(\Vert\) denotes the concatenation operation and \(g(\cdot )\) is the back-projection function implemented via an MLP to align the feature dimensions.

Siamese exchanged attention layer

In order to integrate the features from Q-branch and G-branch more efficiently, we propose an extension to attention, named as Siamese Exchange Attention Layer (SEA), to exchange information between the Q-branch and G-branch in a symmetrical manner, which is shown in the right part of Fig. 3. To be concrete, given the representations \(x^k_\star\) from the shared feature encoder, where \(\star\) can be q or g, the process starts by adapting inputs for query-key-value attention computation. With utilizing three learnable embedding matrices, \({i.e. },\), \({W}_{Q}\), \({W}_{K}\), \({W}_{V}\), the SEA layer first projects the context \(x^k_\star\) into the query \({Q}_\star\), the key \({K}_\star\) and the value \({V}_\star\) respectively. Note that the learnable projection matrices are shared between the Q-branch and G-branch. Hereafter, the interactive attention map is computed via exchanging the query matrix mutually and then performing softmax dot-product between the swapped query \({Q}_g\) (or \({Q}_q\)) and the original key \({K}_q\) (or \({K}_g\)), which can be viewed as content-to-content interaction between two branches. Finally, SEA aggregates the value embeddings \({V}_g\) (or \({V}_q\)) with using the corresponding attention map \({A}_q\) (or \({A}_g\)) as kernel weights separately and then concatenates the output representations from two branch together as a joint feature for next modules. Mathematically, the SEA layer can be formulated as:

where C and h are the embedding dimension and the number of heads, \({W}_{Q}\), \({W}_{K}\), \({W}_{V}\) \(\in \mathbb {R}^{C\times (C/h)}\) are learnable parameters and shared between Q-branch and G-branch. Note that typically, since the query matrix Q of one branch is replaced by the other branch, the computation and memory complexity of generating the attention map A in SEA layer are linear rather than quadratic as in AAF, which makes the entire process more efficient. Moreover, after further employing the multi-heads mechanism with layer normalization and residual shortcut, the output \(z^k\) of SEA layer for a given features pair \(x^k_q\) and \(x^k_g\) is defined as follows:

Intra- and inter-stage scale adaptation

To alleviate the problem of high scale-variance in GOSO, the proposed SEA adapts various-scale matching from two orthogonal view, namely Intra- and Inter-stage. As mentioned in the Section “Siamese exchanged attention module”, the feature maps from the same stage of the backbone are fed into the SEA module, which can be regarded as conducting dense region-to-region matching between query and gallery with the same receptive field, i.e., intra-stage scale adaptation. Concretely, for an object of any scale in the gallery, part of the content (if exists) on its feature map can always correspond to the query one, and then be activated by attention, which is illustrated by the green shade and blue shade in Fig. 3. Moreover, with the bottom-up feed-forward computation of the backbone, one widely intuition is that deep networks combine low-level features to increasingly complex shapes until the object can be readily discriminated56. Therefore, based on the hierarchical structure for different granularity, we apply several SEA layers among multiple stages of the model and then fuse them with a Hierarchical Feature Fusion module (HFF), that is, inter-stage scale adaptation, which can be formulated as:

where N is the number of stages in backbone, GAP represents the global average pooling function, \({Z}^{k}\) is the output of k-th SEA layer and \({B}^N\) is the final fusion feature.

Open score fusion module

Given \(x_q\) and \(x_g\) under the setting of GOSO, with considering the known and unknown spaces simultaneously, a desirable matching score function should be defined as:

where \(f_{K}\) is the convergent parameter space after optimizing on known dataset, \(f_{U}\) represents the part of unknown, \(\phi\) is a pairwise distance function for similarity score and \(\oplus\) defines the final scores fusion operator. According to this definition, we propose the Open Score Fusion module (OSF) with concretizing the \(f_{K}\), \(f_{U}\), \(\phi\) and \(\oplus\) in Eq. (6).

After finetuning on the known dataset \({D}_{K}^{tr}\), \(f_{K}\) actually is the well-parameterized SEA module in Section “Siamese exchanged attention module”. In general, due to the unreachability nature of unknown space, we can only approximate the \(f_{U}\) for feasibility. The most straightforward way is to omit the \(f_{U}\) and then the matching score is completely determined by the \(f_{K}\), usually leading to poor performance due to severe overfitting, which has been also empirically verified in the Tables 1 and 2. Another that is not precise but very practical is to use the large-scale pre-trained model (e.g. ImageNet) to close in \(f_{U}\), which is cost-free to obtain and friendly for downstream tasks. Furthermore, the pairwise distance function \(\phi\) is denoted as cosine similarity and we use summation as the score fusion operator. As stated above, the overall OSF module can be denoted as,

where B is the output feature in the Eq. (5) and P represents that the feature is extracted by the pre-trained model.

Experiments

In this section, we first introduce the experimental setting in Section “Experimental settings” and then employ our approach with other existing baselines on multiple benchmarks in Section “Main results”. Finally, we provide comprehensive ablation studies in Section “Ablation studies”.

Experimental settings

Extending benchmarks

COCO63 is the most widely-used object detection benchmark for common entities, containing 80 categories, 112k images and 1.2M instances with exhaustive annotations. In order to simulate the open nature in GOSO, the 60 categories disjoint with VOC64 are used as known classes while the remaining 20 classes are used as unknown classes. Moreover, according to the number of queries in each category of \({D}^{Q}_{te}\), we further construct the small and large test set, in which there are 20 and 100 queries in each class correspondingly. LVIS65 is a more challenging benchmark for large-vocabulary instance segmentation, containing over 1200 entity labels and naturally retaining a long-tail distribution. As most of them contain few samples (even zero), we select the most frequent 400 categories and randomly split them into 300 for known classes and 100 for unknown, named LVIS-400. Compared to COCO, apart from more categories, LVIS-400 contains more small instances (\(< 32 \times 32\)) and more semantic-similar classes, which greatly increase the difficulty of GOSO.

Evaluation protocol

To better demonstrate the performance of our model, we adopt three classic metrics into our evaluation: (1) mAP, the mean Average Precision, (2) R@K, Recall@Top-K, where K is the number of positive samples for the target query in the gallery, and (3) AUROC, the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve, which is used to evaluate discrimination of retrieval score distribution between positive samples and negative samples in the gallery. For each of the above metrics, we report all results from six dimensions, that is, (1) All (all classes), Known (only known classes), Unknown (only unknown classes), Large (object area \(\geqslant 96\times 96\)), Medium (\(32\times 32 <\) object area \(< 96\times 96\)) and Small (object area \(\leqslant 32\times 32\)). This allows us to observe trends in performance on various openness settings, as well as the impact of the object scale on our approach. Note that all results in the paper are obtained on the large test set (about 100 queries of each category) of each benchmark for reliability.

Implementation details

We train all models for 10 epochs using the AdamW optimizer66 on 8 GPUs with a batch size of 64. We set the initial learning rate as \(\frac{batch size}{1024} \times 0.001\) and decay the learning rate to \(1e^{-5}\) using the cosine schedule. We use a linear warm-up learning rate in the first epoch and apply gradient clipping to stabilize the training process. Moreover, to adapt the CNN structure, the feature maps of each layer in CNN are obtained after the GAP to \(7\times 7\), and then flattened in the spatial dimension.

Main results

Comparisons with different training methods

All results are presented in Tables 1 and 2. First, we evaluate different training methods for GOSO including contrastive unsupervised learning (MoCo57), supervised learning, multi-label learning (Relabel59) based on ResNet-50 (RN50)58 trained on ImageNet. We find that the RN50 trained on Re-labeling ImageNet clearly outperforms other methods. Specifically, RN50-Relabel outperforms RN50 with supervised learning by almost 5%. In contrast, the performance of contrastive unsupervised training is much worse. This also proves that finer-grained annotation for multi-label can effectively improve the performance of GOSO.

Comparisons with different backbones

We compare different transformer-style architectures for GOSO including vision transformers (ViT60, DeiT61 and Swin Transformer62) trained on ImageNet in Tables 1 and 2. Compared to the RN50, ViT and DeiT achieve better performance on mAP and R@K, but do not show obvious advantages on AUROC. The local information is very important for the matching of multi-scale queries and galleries with multi-objects in GOSO. However, the structure of CNN is limited by inductive bias67, resulting in bias error. In contrast, Swin-Transformer gains almost 10% performance improvement. The hierarchical feature representation and multi-scale shifted windows in Swin-Transformer effectively promote the ability to extract effective local features for different scales objects in the gallery.

Comparisons with two finetuning methods

We compare our approach with two fine-tuning methods (Fine-Tuning and Two-stage Fine-Tuning Approach51). The evaluation protocols for these methods are detailed as follows:

-

Fine-Tuning (FT) initializes the model with ImageNet pre-trained weights and subsequently fine-tunes it using multi-label classification on the provided known classes.

-

Two-stage Fine-Tuning Approach (TFA)51 augments the frozen pre-trained model with an adaptive layer (e.g., a self-attention layer) appended after the last layer. This adaptive layer is then trained via multi-label classification using the known dataset. For evaluation, the proposed OSF is integrated into the TFA framework.

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, our method clearly outperforms both of these approaches as well as the baseline. Notably, for the Deit-B backbone on the COCO dataset, our method achieves a significant improvement of 10% in mAP-All compared to the baseline. A closer analysis of the transfer methods relative to the baseline yields several reliable insights. While FT generally enhances performance on known classes across most backbones, it also tends to overfit these classes, which in turn degrades performance on unknown classes and adversely affects overall results. Meanwhile, we observed that while FT can sometimes boost overall performance, it occasionally leads to a decrease on known classes. We attribute this to the fact that our model is trained with a multi-class classification loss, which is not specifically designed for image matching tasks. Consequently, the learned feature representations may lack the necessary discriminative power and robustness for effective matching, as reflected in the mAP results. On the other hand, TFA with OSF mitigates the performance drop on unknown classes; however, much of this gain can be attributed directly to the proposed OSF, as evidenced in Table 5. Particularly with transformer-style backbones, TFA still suffers from overfitting on known classes, leading to declines in unknown class performance. In contrast, our method consistently boosts performance on both known and unknown categories across all backbones. This improvement is not solely due to the integration of OSF; it also stems from our novel query and gallery matching training mechanism based on SEA-Net. Moreover, our approach, which incorporates hierarchical feature fusion, promotes a more balanced improvement across large, medium, and small queries. Figure 4 illustrates several successful examples achieved by our method.

Ablation studies

In this section, we first compare our SEA layer with different fusion schemes, then analyze the effects of our intra- and inter-stage scale adaptation. we finally show the importance of OSF to unknown object search in Open Reality.

Siamese exchanged attention layer

Table 3 shows the performance of different fusions schemes, including AAF (All-Attention Fusion), SA (Siamese-Attention does not exchange the attention map from two branches compared with SEA), SEA (Siamese Exchanged Attention). Among all these strategies, the proposed SEA achieves the best known, unknown, and overall performance on COCO. Despite the use of additional self-attention to combine information between two branches, all-attention with quadratic computation and memory complexity fails to achieve better performance. SA can be regarded as exchanging queries in two branches independent of self-attention, which reduces the consumption of computing and memory and achieves better performance than AAT. The SEA with exchanging the attention map fuses more useful information of the two branches than SA, so as to retain the common features more effectively.

Inter-stage scale adaptation

We perform experiments to understand the effect of inter-stage scale adaptation by testing the different layers combinations in Table 4. We keep the last layer containing more semantics and gradually add front layers. It can be observed that the combination of the last layer and more front layers achieves higher overall performance. Specifically, when only the last several layers are used, better performance is achieved on the large objects search. With the addition of shallow features, SEA-Net has better performance for small and medium objects. On the whole, the combination of all layer features has the best generalization in the search of objects with different scales.

Open score fusion module

Although TFA could maintain unknown performance on several backbones, its gains come from the better generalization ability of the pre-training model. Furthermore, both our method and TFA have different degrees of over-fitting on the known classes, which degrades the performance of the unknown classes as shown in Table 5. Without the help of the pre-training retrieval score, our method not only achieves the best performance on known classes but also performs better than TFA on unknown classes. In addition, the performance of SEA on known classes slightly exceeds the performance of SEA+OSF. Nevertheless, the OSF is still more suitable for open reality with unknown categories.

Computational complexity analysis

To further evaluate the efficiency of our proposed approach, we analyze the computational complexity in terms of both FLOPs and the number of trainable parameters. Specifically, before incorporating our module, our model requires approximately 15.19 GMac of FLOPs and contains 86.83 million parameters. After integrating our module, the computational cost increases to 36.15 GMac, with the total parameter count rising to 118.92 million. Although the inclusion of our module introduces additional computational overhead, the significant performance improvements observed in our experiments justify this trade-off. This analysis demonstrates that our method achieves a favorable balance between computational efficiency and enhanced matching performance in open reality settings.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper extends a valuable and practical vision task, GOSO. Based on multiple granularity stage-stacked fusion mechanisms, we propose an effective matching architecture, that is, SEA-Net. Then, an open score fusion module is adapted during inference for more robust matching scores for both known and unknown queries. Our method achieves SOTA performance on two GOSO evaluation benchmarks. In the future, how to make full use of known classes to improve the generalization of the model on unknown classes is worth further exploration, including but not limited to questing the impact of the number and range of known classes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ma, J., Jiang, X., Fan, A., Jiang, J. & Yan, J. Image matching from handcrafted to deep features: A survey. Int. J. Comput. Vision 129, 23–79 (2021).

Zheng, L., Yang, Y. & Hauptmann, A. G. Person re-identification: Past, present and future. http://arxiv.org/abs/1610.02984 (2016).

Kanacı, A., Zhu, X. & Gong, S. Vehicle re-identification in context. In German Conference on Pattern Recognition, 377–390 (Springer, 2018).

Thong, W., Snoek, C. G. & Smeulders, A. W. Cooperative embeddings for instance, attribute and category retrieval. http://arxiv.org/abs/1904.01421 (2019).

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. & Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 28, 91–99 (2015).

Liu, W., Wang, H., Shen, X. & Tsang, I. The emerging trends of multi-label learning. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2021).

Zheng, L. et al. Person re-identification in the wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 1367–1376 (2017).

Leng, Q., Ye, M. & Tian, Q. A survey of open-world person re-identification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 30, 1092–1108 (2019).

Bedagkar-Gala, A. & Shah, S. K. A survey of approaches and trends in person re-identification. Image Vis. Comput. 32, 270–286 (2014).

Chen, G., Peng, P., Huang, Y., Geng, M. & Tian, Y. Adaptive discovering and merging for incremental novel class discovery. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 11276–11284 (2024).

Zou, Y. et al. Annotation-efficient untrimmed video action recognition. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 487–495 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Anonymous model pruning for compressing deep neural networks. In 2020 IEEE Conference on Multimedia Information Processing and Retrieval (MIPR), 157–160 (IEEE, 2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Micm: Rethinking unsupervised pretraining for enhanced few-shot learning. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 7686–7695 (2024).

Ma, L. et al. Picking up quantization steps for compressed image classification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 33, 1884–1898 (2022).

Liu, H., Tian, Y., Yang, Y., Pang, L. & Huang, T. Deep relative distance learning: Tell the difference between similar vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2167–2175 (2016).

Wang, Z. et al. Orientation invariant feature embedding and spatial temporal regularization for vehicle re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 379–387 (2017).

Liu, Z., Luo, P., Qiu, S., Wang, X. & Tang, X. Deepfashion: Powering robust clothes recognition and retrieval with rich annotations. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 1096–1104 (2016).

Xiao, T., Li, S., Wang, B., Lin, L. & Wang, X. End-to-end deep learning for person search. http://arxiv.org/abs/1604.01850 (2016).

Xiao, T., Li, S., Wang, B., Lin, L. & Wang, X. Joint detection and identification feature learning for person search. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 3415–3424 (2017).

Lan, X., Zhu, X. & Gong, S. Person search by multi-scale matching. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 536–552 (2018).

Wu, F. et al. Cross-media semantic representation via bi-directional learning to rank. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM International conference on Multimedia, 877–886 (2013).

Castrejon, L., Aytar, Y., Vondrick, C., Pirsiavash, H. & Torralba, A. Learning aligned cross-modal representations from weakly aligned data. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2940–2949 (2016).

Zhai, A. & Wu, H.-Y. Classification is a strong baseline for deep metric learning. http://arxiv.org/abs/1811.12649 (2018).

Krause, J., Stark, M., Deng, J. & Fei-Fei, L. 3d object representations for fine-grained categorization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, 554–561 (2013).

Welinder, P. et al. Caltech-Ucsd Birds 200 (California Institute of Technology, 2010).

Oh Song, H., Xiang, Y., Jegelka, S. & Savarese, S. Deep metric learning via lifted structured feature embedding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 4004–4012 (2016).

Fan, B. et al. A performance evaluation of local features for image-based 3d reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 28, 4774–4789 (2019).

Yi, K. M. et al. Learning to find good correspondences. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2666–2674 (2018).

Wu, J., Zhang, H. & Guan, Y. Visual loop closure detection by matching binary visual features using locality sensitive hashing. In Proceeding of the 11th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation, 940–945 (IEEE, 2014).

Liu, Y. & Zhang, H. Indexing visual features: Real-time loop closure detection using a tree structure. In 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 3613–3618 (IEEE, 2012).

Zhou, W., Li, H. & Tian, Q. Recent advance in content-based image retrieval: A literature survey. http://arxiv.org/abs/1706.06064 (2017).

Zitnick, C. L. & Ramnath, K. Edge foci interest points. In 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, 359–366 (IEEE, 2011).

Jégou, H., Douze, M. & Schmid, C. Improving bag-of-features for large scale image search. Int. J. Comput. Vision 87, 316–336 (2010).

Li, H., Chen, J., Zheng, A., Wu, Y. & Luo, Y. Day-night cross-domain vehicle re-identification. In 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 12626–12635 (2024).

Qiu, L. et al. High-order structure based middle-feature learning for visible-infrared person re-identification. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2023).

Ye, M. et al. Transformer for object re-identification: A survey. http://arxiv.org/abs/2401.06960abs/ (2024).

Wu, T., Huang, Q., Liu, Z., Wang, Y. & Lin, D. Distribution-balanced loss for multi-label classification in long-tailed datasets. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 162–178 (Springer, 2020).

Ridnik, T. et al. Asymmetric loss for multi-label classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 82–91 (2021).

Ben-Baruch, E. et al. Multi-label classification with partial annotations using class-aware selective loss. http://arxiv.org/abs/2110.10955 (2021).

Chen, T., Xu, M., Hui, X., Wu, H. & Lin, L. Learning semantic-specific graph representation for multi-label image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 522–531 (2019).

Chen, Z.-M., Wei, X.-S., Jin, X. & Guo, Y. Multi-label image recognition with joint class-aware map disentangling and label correlation embedding. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), 622–627 (IEEE, 2019).

You, R. et al. Cross-modality attention with semantic graph embedding for multi-label classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 12709–12716 (2020).

Wang, Z., Chen, T., Li, G., Xu, R. & Lin, L. Multi-label image recognition by recurrently discovering attentional regions. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 464–472 (2017).

Liu, S., Zhang, L., Yang, X., Su, H. & Zhu, J. Query2label: A simple transformer way to multi-label classification. http://arxiv.org/abs/2107.10834 (2021).

Bendale, A. & Boult, T. E. Towards open set deep networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 1563–1572 (2016).

Chen, G. et al. Learning open set network with discriminative reciprocal points. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part III 16, 507–522 (Springer, 2020).

Chen, G., Peng, P., Wang, X. & Tian, Y. Adversarial reciprocal points learning for open set recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3106743 (2021).

Joseph, K., Khan, S., Khan, F. S. & Balasubramanian, V. N. Towards open world object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 5830–5840 (2021).

Qiao, L. et al. Transductive episodic-wise adaptive metric for few-shot learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 3603–3612 (2019).

Chen, W.-Y., Liu, Y.-C., Kira, Z., Wang, Y.-C. F. & Huang, J.-B. A closer look at few-shot classification. http://arxiv.org/abs/1904.04232 (2019).

Wang, X., Huang, T., Gonzalez, J., Darrell, T. & Yu, F. Frustratingly simple few-shot object detection. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 9919–9928 (PMLR, 2020).

Qiao, L. et al. Defrcn: Decoupled faster r-cnn for few-shot object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 8681–8690 (2021).

Fan, Q., Zhuo, W., Tang, C.-K. & Tai, Y.-W. Few-shot object detection with attention-rpn and multi-relation detector. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 4013–4022 (2020).

Chen, C.-F., Fan, Q. & Panda, R. Crossvit: Cross-attention multi-scale vision transformer for image classification. http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.14899 (2021).

Zhang, H., Goodfellow, I., Metaxas, D. & Odena, A. Self-attention generative adversarial networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 7354–7363 (PMLR, 2019).

Kriegeskorte, N. Deep neural networks: A new framework for modeling biological vision and brain information processing. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 1, 417–446 (2015).

He, K., Fan, H., Wu, Y., Xie, S. & Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 9729–9738 (2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Yun, S. et al. Re-labeling imagenet: from single to multi-labels, from global to localized labels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2340–2350 (2021).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2020).

Touvron, H. et al. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 10347–10357 (PMLR, 2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) (2021).

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 740–755 (Springer, 2014).

Everingham, M., Van Gool, L., Williams, C. K., Winn, J. & Zisserman, A. The pascal visual object classes (voc) challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vision 88, 303–338 (2010).

Gupta, A., Dollar, P. & Girshick, R. LVIS: A dataset for large vocabulary instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2019).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.05101 (2017).

Goyal, A. & Bengio, Y. Inductive biases for deep learning of higher-level cognition. http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.15091 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Postdoctoral Program of Smart Tower Co., Ltd.; the Shenzhen High-Level Talent Team Program and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (Grant No. KQTD 20240729102051063); as well as Phase I and Phase II Research Projects on Large-Scale Models for the Spatial Governance Industry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S. and W.M. conceptualized the experiments. G.S. and G.C. carried out the experiments. G.S., W.M., G.C., and Y.T. analyzed the results. All authors contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, G., Ma, W., Chen, G. et al. Toward general object search in open reality. Sci Rep 15, 13523 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97251-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97251-5