Abstract

Our study examined how metabolic syndrome (MetS) affects the risk of small airway dysfunction (SAD) and its progression to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). We also investigated the role of inflammation in mediating these effects. We included 13,948 non-COPD participants, aged 40 years and with a pulmonary function test, from multiple communities (Longquan, Mianzhu, and Pidu), and subsequently followed up the Longquan community after 3 years. Logistic models estimated the association between MetS and SAD risk, adjusted for confounders. Furthermore, a mediation analysis approach was employed to estimate the proportion of effect mediated by each marker of inflammation (e.g., the low-grade inflammation index) on the observed association. In West China Natural Population Cohort Study(WCNPCS), compared to the non-MetS group, individuals with MetS showed a significantly higher prevalence of SAD (odds ratio [OR] = 1.12, 1.02–1.22); however, this was not significant in women. For MetS components, high triacylglycerols(HTG), low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LHDL-C) and abdominal obesity (AO) were independent risk factors for SAD, which is consistent with men (OR = 1.09–1.33). In addition, the more metabolic disorder components, the higher the prevalence of SAD (P < 0.05). Further, when MetS as well as SAD outcomes were considered together, the incidence of COPD in individuals with both these irregularities was considerably higher (9-fold). Inflammation (the proportion of effect mediated: 14.3–28.6%) played a substantial mediating role in the observed association in Chinese participants. MetS is consistently linked to SAD and may facilitate progression from SAD to COPD; its components, HTG, LHDL-C and AO, were associated with a significantly increased risk of COPD. The observed associations were partly mediated by inflammation. Treating MetS may be an effective strategy for the prevention of the development of COPD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide as well as being a major incurable global health burden1. Using the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease(GOLD) definition, The prevalence of COPD among people aged 30–79 years was 10.3% in 20192. With increasing aging populations in high-income countries, the prevalence of COPD is expected to rise. Small airways are generally defined as airways with a luminal diameter < 2 mm. Small airway dysfunction (SAD) is therefore considered a precursor of COPD3. The global prevalence of SAD currently lacks official data, with available prevalence estimates ranging from 6.4–53.8%4,5, while the prevalence of SAD in China is as high as 43.5%6. People with SAD are more likely to develop COPD in the future6. Assessment of Renal and Cervical Artery Dysplasia-Poland(ARCADIA) study found that the severity of SAD is related to acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) and mortality7. GOLD emphasized the clinical importance of SAD recognition in the implementation of earlier interventions8. However, little is known about what determines this progression.

Earlier observational reports have described that Mets was associated with an increased risk of COPD9. And COPD can also predispose to Metabolic syndrome (MetS). MetS includes obesity, dysglycemia, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LHDL-C) levels, which were inversely related with lung function, especially obesity10. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and its components increases significantly with age, particularly after the 40 years11. Previous studies have demonstrated that the components of Mets (diabetes and hypertension) can affect small airway function12,13. Inflammation, smoking, physical inactivity and adipokine dysregulation may contribute to the link between MetS and SAD or COPD14,15. However, knowledge is lacking regarding the correlation between MetS and SAD, and evidence of Mets to predict SAD progression to COPD. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investigate this association among Chinese individuals aged 40 years and older who completed a 3-year follow-up and We also investigated the role of inflammation in mediating these effects.

Methods

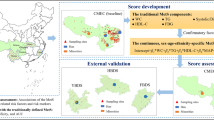

Study population and design

Cross-sectional study data were taken from the Natural Population Cohort Study of West China Hospital of Sichuan University, a longitudinal study conducted in communities that was started in Longquan in 2019 (with the first wave in 2019 and the second in 2020), in Mianzhu in 2020, and in Pidu in 202116. In brief, baseline data for 13,948 non-COPD participants aged 40 years with a pulmonary function test from multiple communities (Longquan, Mianzhu, and Pidu) were selected. The investigators underwent extensive training with regard to the study questionnaire and outcome measures prior to the beginning of the investigation. Participants were excluded according to the following parameters: pregnancy, lack of mobility, old age (> 85 years of age), weakness, communication barriers, poor compliance, history of long-term chronic disease, recent acute disease, those with one of the following diseases in the previous 6-month period: liver cirrhosis, stroke, myocardial infarction and malignant tumour; and those with respiratory diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and bronchiectasis, among others.

Each participant provided written informed consent relating to their participation in this study. In accordance with the ethics standards in the Declaration of Helsinki, ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University.

Follow-up study

The longitudinal analysis was restricted to 1,667 participants with a pulmonary function test recruited in the Longquan region in September 2020, with approximately 3 years of follow-up to August 2023. The occurrence of COPD incorporated new self-reports of physician-diagnosed COPD (acquired yearly), and newly diagnosed COPD by pulmonary function test (during the third year).

MetS and its components

MetS was defined based according to International Diabetes Federation criteria17 when three of the following five components were present: (1) abdominal obesity (AO): waist circumferenc (WC) ≥ 90 cm in men and ≥ 80 cm in women (specific cut-off value for Asians); (2) High fasting plasma glucose (HFPG) ≥ 5.6 mmol/L or the use of glucose-lowering drugs; (3) High blood pressure (HBP): systolic BP ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 85 mmHg or receiving antihypertensive medications; (4) Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LHDL-C): fasting HDL-C < 1.0 mmol/L in men and < 1.3 mmol/L in women; (5) High triglycerides (HTG): fasting TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L or use of lipid-modifying drugs.

We briefly describe how BP, WC, and lipid and glucose levels were measured: During the baseline interview, a physical examination was carried out, during which BP was measured at the right brachial artery three times in a seated position, at 5-min intervals, using an automatic sphygmomanometer. Waist circumference was measured horizontally around the narrowest part of the torso, between the lowest rib and the iliac crest. Blood samples were obtained the morning following an 8-h overnight fast. FPG, TG, and HDL-C were determined by a glucose oxidase method, colorimetric enzyme assays, as well as endpoint colorimetry respectively.

SAD and COPD

A pulmonary function test was performed by trained medical technicians using a portable spirometer (MasterScreen Pneumo, Hoechberg, Germany) according to the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society. The indicators of forced expiratory flow (FEF)50%, FEF75% and FEF25–75%, also known as maximum midexpiratory flow, are the most frequently used to evaluate the function of small airways. It is now generally accepted that SAD exists when two of the above three indicators are below the expected value of 65%18. The forced expiratory volume in one second divided by forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) was commonly used for assessing airflow limitation, with FEV1/FVC < 0.7 indicating the presence of COPD1.

Mediators: low-grade inflammation

Low-grade inflammation index(LGII) was included in 10 tiles of leukocyte (WBC, ×109/L) and platelet counts (×109/L), and the granulocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (G/L ratio). Specifically, the three indicators in the population were distributed in tenth place, where the highest (7th to 10th) had a positive score of 1 to 4 points, the lowest (1st to 4th) had a negative score of -4 to -1 points, and the middle (5th to 6th) was 0 points. A total score for low-grade inflammation (between − 12 and 12) was calculated for each person. An increase in the score represented an increase in the intensity of low-grade inflammation19.

Covariates

During the baseline interview, all participants were asked about their gender, age, history of diabetes and hypertension, smoking history, alcohol intake and Physical activity. A detailed smoking history was obtained and individuals classified as: never, occasionally, former or current smokers. Drinking was defined as more than 30 g per week in the last 12 months. Physical activity was classified as: Never or few, 2–3 times/month, 1–2 times/week, > 3 times/week.

Statistical analysis

The statistical package, SPSS 19.0, was used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD, and two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous variables were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance. If the difference was statistically significant, a Bonferroni method was used for pairwise comparison. Categorical variables were analyzed via a χ2 test. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the influence of factors related to MetS on SAD. A mediation analysis approach based on the bootstrap method proposed by Preacher and Hayes through R-packet ‘mediating’ to explore whether inflammation could be modes or mechanisms by which Mets influences on the SAD20. All inflammatory indicators were standardized prior to the analysis. The mediation model was adjusted for gender, age, job, smoking, alcohol, BMI and physical activity. To examine the potential nonlinear relationships between the five components of metabolic syndrome and subclinical atherosclerosis disease (SAD), restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression analysis was conducted. The statistical analyse was performed with R software version 4.3.1.

Results

The 13,498 participants ranged in age from 40 to 85 years (53.83 ± 10.21 years). Of these, 3,330 (24.7%) were patients with MetS, and more women (2,349, 17.4%) than men ( 981, 7.3%) were classified with MetS. Compared to those without MetS, the mean age of individuals with MetS was 4.72 years older.The levels of FPG, TG, LDL-C, WC, systolic BP, diastolic BP, WBC, granulocytes and low-grade inflammation in the MetS population were significantly higher than those in the non-MetS population (P < 0.001). Conversely, the levels of HDL-C and FEF25–75% in the non-MetS population were significantly higher than those in the MetS population (P < 0.01; Table 1).

The prevalence of SAD in Mets was 64.62% (Figure S1), and a greater proportion of women(66.96%) than men (59.02%) were classified with SAD (P < 0.05). The prevalence of SAD increased steadily with the number of Mets components (Figure S2).

Association of individual MetS components with risk of SAD

MetS was significantly correlated with the occurrence of SAD and was a risk factor for SAD (odds ratio [OR] = 1.12, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02 to 1.22). HTG(OR = 1.09, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.17), LHDL-C (OR = 1.25, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.39) and AO (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.28) were found to be independent risk factors for SAD. For SAD, four components (OR = 1.31) showed the highest OR, followed by three (OR = 1.14) components (Fig. 1).

Comparisons of the odds ratios for small airways disease (SAD) based on the components and the number of components of metabolic syndrome.

Notes: Model adjusted for age, gender, Job, Smoking, Alcohol, BMI and physical activity. Abbreviations: MetS, metabolic syndrome; CI, confidence interval; HBP, high blood pressure; AO, abdominal obesity; HTG, high triacylglycerols; HFPG, high fasting plasma glucose; LHDL-C, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

The association of individual MetS components with the risk of SAD by gender

After adjusting for age, job, smoking, alcohol, BMI and physical activity, the relationship between Mets and SAD in women (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.94–1.17; P = 0.42) was found not to be significant. The variables, LHDL-C and AO, were independent risk factors for SAD (OR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.08–1.37; P = 0.001 and OR: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.04–1.28; P = 0.007). MetS was found to be an independent risk factor for SAD in men after adjusting for age, job, smoking, alcohol, BMI and physical activity (OR: 1.28; 95% CI: 1.09–1.50; P = 0.002). The variables, HTG, LHDL-C and AO were independent risk factors for SAD (OR: 1.16; 95% CI: 1.01–1.31; P = 0.03, OR: 1.33; 95% CI: 1.04–1.70; P = 0.02 and OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.02–142; P = 0.03) (Table 2).

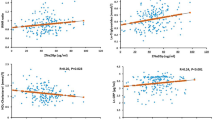

The relationship between components of metabolic syndrome and SAD

A significant nonlinear association was observed between FPG, TG, HDL-C, SBP, and SAD in the fully adjusted restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression model ( p for nonlinearity < 0.05). However, no nonlinear relationship was found between WC, DBP and SAD.(Fig. 2)

Development of COPD

A total of 1,667 participants with a pulmonary function test were followed up. in longquan. From baseline to 76 (4.56%), participants who progressed to COPD underwent a pulmonary function test. The population was divided into Normal group, isolated SAD group, isolated Mets group, and MetS + SAD group. Of the 76 participants with incident COPD, seven (0.94%) were in the Nomal group, 52 (8.86%) in the isolated SAD group, three (1.68%) in the isolated MetS group, and 14 (9.09%) in the MetS + SAD group. The cumulative total progression rate to COPD was highest in the MetS + SAD group (9.09%, P < 0.05), followed by isolated SAD group (8.86%), isolated MetS group (1.69%), and Nomal group(0.94%). If the relative risk of Nomal group, to COPD after a 3-year follow-up was set to 1, after adjusting for age, job, smoking, alcohol, BMI and physical activity, the risk of progression to COPD in isolated SAD group, isolated MetS, and MetS + SAD groups was increased 7.80 times (95% CI 3.33–23.26), 0.03 times (95% CI 0.21–5.12), and 9.36 times (95% CI 4.58–23.46), respectively (Table 3).

Role of inflammation

For the observed associations between MetS and SAD risk, WBC, neutrophile granulocyte(NEU) and LGII played significant mediated effects, albeit with varying degrees of magnitude. For the SAD prevalence risk, WBC, NEU, and LGII had effects ranging from 14.3–28.6% (Fig. 3). For the observed associations between MetS and COPD incidence, WBC, NEU and LGII showed non-significant effects.

Abbreviations: MetS, metabolic syndrome. WBC: White blood cell. NEU: Nranulocyte. LGII: Low-grade inflammation index. Notes: adjusted for gender, age, job, smoking, alcohol, BMI and physical activity.

Discussion

Our research across a community-based cohort in China investigated whether MetS can increase the risk of SAD and the likelihood of developing COPD and the role of inflammation in mediating these effects. We found that, compared to the non-MetS group, individuals with MetS showed a significantly higher prevalence of SAD. Furthermore, the current study also assessed the effect of MetS on the progression from SAD to COPD among the general population in Western China. When MetS as well as SAD outcomes were considered together, the incidence of COPD in individuals with both these irregularities was considerably higher (9-fold). In addition, we also found that the MetS components, HTG, LHDL-C and AO, were independent risk factors for SAD. Notably, the relationship between MetS and SAD was significantly mediated by inflammation. These insights suggest that modifying MetS, along with targeting inflammation, may be effective strategies for reducing the risk of SAD and COPD.

SAD typically occurs during the onset of COPD symptoms or a decline in lung function and is often evident before imaging changes become apparent21. SAD occurs in patients at all stages of COPD, manifesting as inflammation and remodelling which progresses to airway destruction22. A 5-year follow-up prospective study found that 70.4% of patients with COPD exhibited SAD and emphysema and 23.0% of patients with the Tissue→Airway subtype in which SAD and emphysema preceded large airway wall abnormalities and 8.7% of subjects without SAD progressed to COPD23. This is higher than the 8.91% observed in patients with SAD in our study. This difference may be attributed to the short follow-up period in this study and the use of GOLD stage 2 diagnostic criteria for COPD.

MetS is a serious public health concern that not only increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality24 but is also closely linked to the respiratory condition, COPD9. No study has evaluated the association between MetS and SAD; But, there are few studies on metabolic syndrome and COPD. A cross-sectional analysis of Israeli adults insured with a single health maintenance organization during 2010 to 2013 revealed that MetS was not associated with COPD25. In a Chinese sample, airflow obstruction was found to be associated with MetS, particularly its central obesity component26. The largest cross-sectional studies in a French population of 121,965 adults showed that after adjusting for sex, age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, education, BMI, and physical activity, MetS was associated with a greater impairment in lung function (defined as FEV1 or FVC < lower limit of normal)10. In a UK Biobank Study, They found that MetS was associated with an increased 24% risk of subsequent developed COPD9. In our cohort study, MetS was significantly associated with a increased risk of SAD and increasing the progression of SAD to COPD. Interleukin (IL)-6 and C-reactive protein are key characteristic of MetS and these inflammatory markers are also closely associated with the occurrence and progression of COPD27,28.

Our study revealed a significant relationship between MetS and SAD in men, which was not observed in women. This is consistent with a Korean study, which demonstrated an association between MetS and COPD only in men29. The disparity in results may be attributed to historic patterns of smoking and occupational exposures in men2. With regard to the components of MetS, we found a significant association between HTG, LHDL, AO and SAD. This is consistent with Previous researchs. A large-scale retrospective cohort demonstrated that patients with hyperlipidemia presented a 1.48-fold greater risk of subsequently developing COPD than individuals without hyperlipidaemia30. Another study demonstrated that TG exhibits a positive correlation with COPD31. Shared pathogenic mechanisms, such as chronic systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress, may contribute to this association30,31. In a Chinese cohort study, after adjustment for BMI, waist circumference showed a positive association with the risk of COPD32. A meta-analysis found that measures of lung function decreased among obese adults33. The possible mechanism underlying the association between AO and SAD or COPD is related to inflammation34.However, in our study, no significant association was observed between HFPG, HBP and SAD. A plausible explanation for this observation may lie in the fact that individuals with HFPG and HBP are typically undergoing FPG and BP-lowering therapies. Prior research has demonstrated that hypoglycemic agents, including metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and SGLT-2 inhibitors such as empagliflozin, possess notable anti-inflammatory properties, which may serve to mitigate chronic inflammation within the small airways35,36,37. Research conducted on animal models has revealed that angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), including valsartan, have the potential to mitigate airway inflammation through the inhibition of key inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-α38.

The RCS revealed a significant nonlinear relationship between FPG, TG, HDL-C, SBP and SAD. These findings underscore the importance of maintaining FPG, TG, HDL-C, and SBP within specific ranges, which could offer novel perspectives for the prevention of SAD.

But the mechanisms connecting Mets distribution to SAD or COPD have been extensively investigated but remain incompletely understood. Systemic inflammation included an elevated WBC count, plasma CRP, interleukin (IL)-6 and fibrinogen and Neutrophil; these may be good biomarkers for mortality and exacerbations in SAD and COPD39,40. Metabolic syndrome is often accompanied by a chronic low-grade inflammation41. Previous studies have shown that a cascade of inflammatory processes leads to SAD and impaired lung function42. Inflammatory changes in the small airways are fundamental mechanisms that drive the progression and severity of COPD. Mirrakhimov summarized the current literature on COPD, MetS, and DM, and affirmed that MetS may increase the risk of a COPD exacerbated by associated the elevation of C-reactive protein (CRP)43. Regarding the components of MetS, abdominal fat is known to be more pro-inflammatory44. It has been suggested that the inflammatory response caused by adipose tissue is the key to the impairment in lung function caused by MetS45. These findings support our study’s conclusion that inflammation significantly mediates the relationship between adverse MetS and the risk of SAD.

However, the study also has several limitations. First, the relatively short duration of our follow-up limited the statistical power to identify associations with the development of COPD diseases in China. Second, the assessment of inflammation was based on WBC, granulocytes, and the total score of low-grade inflammation, without further confirmation by C-reactive protein, IL-6 or other inflammatory markers. However, WBC, granulocytes and the total score of low-grade inflammation is recognized as a validated tool for identifying individuals with inflammation. Third, mediation analysis evaluates the role of an intermediate variable (the mediator) in the causal link between an independent variable (the exposure) and a dependent variable (the outcome) over time. However, in our study, both the mediator and the exposure were measured only at baseline. These findings indicate that treating MetS may be an effective strategy for preventing the development of SAD and the progression to COPD.

Conclusions

In conclusion, We first report how metabolic syndrome (MetS) affects the risk of small airway dysfunction (SAD) and its progression of SAD to COPD. In this study, we report the following novel findings. First, compared to the non-MetS group, individuals with MetS showed a significantly higher prevalence of SAD, but not significant in women. Second, We also found that in the metabolic syndrome components, HTG, LHDL-C and AO were independent risk factors for SAD, which is consistent with men. But in women LHDL-C and AO were independent risk factors for SAD. Finally, when MetS as well as SAD outcomes are considered together, the incidence of COPD in individuals with both these irregularities was considerably higher (9-fold). The observed associations were partly mediated by inflammation.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SAD:

-

small airway disease

- MetS:

-

metabolic syndrome

- FPG:

-

fasting plasma glucose

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- HDL-C:

-

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

diastolic blood pressure

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- FEV1:

-

forced expiratory volume in one second

- FVC:

-

forced vital capacity

- FEF:

-

forced expiratory flow

- NEU:

-

Nranulocyte

- LGII:

-

Low-grade inflammation

References

Vogelmeier, C. F. et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 195 (5), 557–582. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP (2017).

Adeloye, D. et al. Global, regional, and National prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 10 (5), 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00511-7 (2022).

Stockley, J. A. et al. Maximal mid-expiratory flow detects early lung disease in α1 -antitrypsin deficiency. Eur. Respir J. 49 (3), 1602055. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02055-2016 (2017).

Manoharan, A., Anderson, W. J., Lipworth, J. & Lipworth, B. J. Assessment of spirometry and impulse oscillometry in relation to asthma control. Lung 193 (1), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-014-9674-6 (2015).

Karlinsky, J. B. et al. Late prevalence of respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function abnormalities in Gulf war I veterans. Arch. Intern. Med. 164 (22), 2488. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.22.2488 (2004).

Xiao, D. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of small airway dysfunction, and association with smoking, in China: findings from a National cross-sectional study. Lancet Respiratory Med. 8 (11), 1081–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30155-7 (2020).

Rogliani, P. et al. Assessing the relationship between cardiovascular and small airway disease and acute events in COPD: the ARCADIA study protocol. Pulm Pharmacol. Ther. 82, 102231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2023.102231 (2023).

Cornelius, T. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: GOLD COPD update 2024. J. Hosp. Med. 19 (9), 818–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.13416 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Metabolic syndrome, genetic susceptibility, and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the UK biobank study. Diabetes Obes. Metabolism. 26 (2), 482–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.15334 (2024).

Leone, N. et al. Lung function impairment and metabolic syndrome: the critical role of abdominal obesity. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 179 (6), 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200807-1195OC (2009).

Aguilar, M., Bhuket, T., Torres, S., Liu, B. & Wong, R. J. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the united States, 2003–2012. JAMA 313 (19), 1973–1974. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.4260 (2015).

Sinclair, A. J., Conroy, S. P. & Bayer, A. J. Impact of diabetes on physical function in older people. Diabetes Care. 31 (2), 233–235. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc07-1784 (2008).

Nathan, S. D., Noble, P. W. & Tuder, R. M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension: connecting the Dots. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 175 (9), 875–880. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200608-1153CC (2007).

Hosseini-Esfahani, F. et al. Using machine learning techniques to predict factors contributing to the incidence of metabolic syndrome in Tehran: cohort study. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 7 (9), e27304. https://doi.org/10.2196/27304 (2021).

Fekete, M. et al. Metabolic syndrome in patients with COPD: causes and pathophysiological consequences. Physiol. Int. Published Online March. 3 https://doi.org/10.1556/2060.2022.00164 (2022).

Peng, A. et al. Association between early parental death and loneliness in adulthood: A Community-Based study in Southwest China. Front. Psychiatry. 13, 784000. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.784000 (2022).

Alberti, K. G. M. M., Zimmet, P. & Shaw, J. Metabolic syndrome—a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the international diabetes federation. Diabet. Med. 23 (5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x (2006).

Zhao, N. et al. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry is associated with small airway dysfunction and reduced total lung capacity. Respir Res. 23 (1), 298. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02216-1 (2022).

Pounis, G. et al. Polyphenol intake is associated with low-grade inflammation, using a novel data analysis from the Moli-sani study. Thromb. Haemost. 115 (02), 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1160/th15-06-0487 (2016).

Hayes, A. F. & Preacher, K. J. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Brit J. Math. Statis. 67 (3), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12028 (2014).

Singh, D., Long, G., Cançado, J. E. D. & Higham, A. Small airway disease in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights and implications for the clinician. Curr. Opin. Pulm Med. 26 (2), 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0000000000000637 (2020).

Koo, H. K. et al. Small airways disease in mild and moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Respir Med. 6 (8), 591–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30196-6 (2018).

Young, A. L. et al. Disease progression modeling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 201 (3), 294–302. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1600OC (2020).

Neeland, I. J. et al. Metabolic syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 10 (1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-024-00563-5 (2024).

Rayyan Assi, H., Ziv, A. & Dankner, R. The metabolic syndrome and its components are differentially associated with chronic diseases in a high-risk population of 350 000 adults: A cross‐sectional study. Diabetes Metabolism Res. 35 (4), e3121. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3121 (2019).

Lam, K. B. H. et al. Airflow obstruction and metabolic syndrome: the Guangzhou biobank cohort study. Eur. Respir J. 35 (2), 317–323. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00024709 (2010).

Huang, H. et al. Interleukin-6 is a strong predictor of the frequency of COPD exacerbation within 1 year. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 16, 2945–2951. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S332505 (2021).

Eley, V. A., Thuzar, M., Navarro, S., Dodd, B. R. & van Zundert, A. A. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and inflammation: an update for anaesthetists caring for patients with obesity. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 40 (6), 100947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2021.100947 (2021).

Park, B. H. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and metabolic syndrome: a nationwide survey in Korea. int. J. Tuberc Lung Dis. 16 (5), 694–700. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.11.0180 (2012).

Yang, H. Y. et al. Increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with hyperlipidemia: A nationwide Population-Based cohort study. IJERPH 19 (19), 12331. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912331 (2022).

Huang, P. et al. Causal relationships between blood lipid levels and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A Mendelian randomization analysis. COPD 20, 83–93. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S476833 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Association between adiposity measures and COPD risk in Chinese adults. Eur. Respir J. 55 (4), 1901899. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01899-2019 (2020).

Forno, E., Han, Y. Y., Mullen, J. & Celedón, J. C. Overweight, obesity, and lung function in children and Adults-A Meta-analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 6 (2), 570–581e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.07.010 (2018).

Barnes, P. J. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin. Chest. Med. 35 (1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2013.10.004 (2014).

Bharath, L. P. & Nikolajczyk, B. S. The intersection of Metformin and inflammation. Am. J. Physiology-Cell Physiol. 320 (5), C873–C879. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00604.2020 (2021).

Alluri, A. A. et al. Exploring the therapeutic potential of GLP-1 receptor agonists in the management of obstructive sleep apnea: a comprehensive review. J. Basic. Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 36 (1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbcpp-2024-0193 (2025).

Lee, Y. E. & Im, D. S. SGLT2 inhibitors empagliflozin and Canagliflozin ameliorate allergic asthma responses in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (14), 7567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25147567 (2024).

Weber, J. et al. Inhibition of Renin angiotensin aldosterone system causes abrogation of obliterative airways disease through Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α-dependant interleukin-17. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 31 (4), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2011.12.012 (2012).

Agustí, A. et al. Persistent Systemic Inflammation is Associated with Poor Clinical Outcomes in COPD: A Novel Phenotype. De Torres JP, ed. PLoS ONE. ;7(5):e37483. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037483

Day, K. et al. Interrelationships among small airways dysfunction, neutrophilic inflammation, and exacerbation frequency in COPD. Chest 159 (4), 1391–1399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.11.018 (2021).

Giri, A. P. & Shanmugam, L. An update on inflammatory markers in metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Adv. Med. 8 (6), 852. https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3933.ijam20212111 (2021).

Oit-Wiscombe, I., Virág, L., Kilk, K., Soomets, U. & Altraja, A. Pattern of expression of genes involved in systemic inflammation and glutathione metabolism reveals exacerbation of COPD. Antioxid. (Basel). 13 (8), 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13080953 (2024).

Mirrakhimov, A. E. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and glucose metabolism: a bitter sweet symphony. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 11 (1), 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-11-132 (2012).

Tilg, H., Ianiro, G., Gasbarrini, A. & Adolph, T. E. Adipokines: masterminds of metabolic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. Published Online November. 7 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-024-01103-8 (2024).

Chan, S. M. H., Selemidis, S., Bozinovski, S. & Vlahos, R. Pathobiological mechanisms underlying metabolic syndrome (MetS) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): clinical significance and therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol. Ther. 198, 160–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.02.013 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank staff of Department of Clinical Research Management of West China Hospital who aided in participant recruitment, and all study participants.

Funding

This work was supported by 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (grant no. ZYGD18017 to NT) Key Research, Development Project of Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Department (grant no. 2023YFS0078 to SX) and National Health Commission key research and development project(grant no.2017YFC1309805-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QX, and SX are responsible for the study’s concept and design. SX and QW did the data and project management. QX did the data cleaning and analysis. QX, SX, and NT interpreted the data. QX, SX, QW and NT drafted the manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval of this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee, West China Hospital, Sichuan University. Fully informed, written consent was obtained from the participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, Q., Xu, S., Wan, Q. et al. Metabolic syndrome, small airway dysfunction and the mediating role of inflammation. Sci Rep 15, 12555 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97326-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97326-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Understanding the causal effects and heterogeneity between metabolic syndrome and lung function: a nationwide prospective cohort study in China

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2025)