Abstract

The uniqueness of each environmental context urgently requires a new vision of environmental and health protection. We propose a new view of environmental diseases that focuses on the value of the individual locality rather than on the generalisations smoothing out differences. By focusing on paleoenvironmental reconstructions, the Pro-Anthropocene data show trajectories that led to and explain the current developments. The evolution of local biodiversity and its transformations over time reveal differentiating elements not only based on the current appearance but also on long-time trajectory of each site. We gathered data from archaeological sites and surrounding ancient landscapes in Italy, drawing from 1,208 pollen spectra. Italy serves as a prime example of a bio-cultural hotspot. By means of β-diversity-based statistical analyses to assess biological uniqueness of the sites, we tested the hypothesis that, despite the low taxonomic resolution of pollen identification and the uniformity of anthropogenic habitats, many sites would result floristically unique. We discuss the role of archaeological sites as robust support for sustainability through nature-based solutions. Drawing for the first time a parallel between workflows in precision medicine and palaeoecology, we propose that a site-specific study—referred to as Precision Land Knowledge of the Past (PLKP)—is crucial for planning effective conservation and restoration efforts. While recognising the resilience of ecosystems, this innovative approach promises to have the power to raise public awareness of the importance of caring for nature.

Similar content being viewed by others

In the third millennium, the biosphere is facing an unprecedent transformation, triggered by an ongoing climate change inextricably linked to the health and functioning of ecosystems1. A series of actions are planned to improve the resilience of ecosystems and prevent climate and human-induced alterations. The link between culture and land use is indisputable, with evidence from studies of the current state2 or reconstructions of past environments3. Palaeoecology is developing increasingly sophisticated models for large-scale global projection4,5, that are of extraordinary effectiveness for palaeoenvironmental reconstructions on a wide scale. However, each ecosystem is unique, and each site is different. Local institutions often call for concrete actions to promote the management of natural resources, and such actions strictly depend on the local variables. In this perspective, palaeoecological and archaeological information should be incorporated into ecology to create diachronic models and increase the effectiveness of ecosystems conservation.

Palaeoenvironmental research has proved that understanding patterns and effects of environmental dynamic processes, including climate-resilience and human agency on one site, needs long-term datasets. Such concepts have been largely accepted by the scientific community, but not many successful examples of application are available6. In recent years, advanced interdisciplinary studies have been reported starting from the experience of archaeological and Quaternary scientists, such as the ArchaeoGLOBE network7, the PAGES LandCover6k working group8,9 and the BRAIN-Botanical Records of Archaeobotany Italian Network10. This approach needs to combine consilience and long-term syntheses. The palaeoresearch provides data on past cultural processes deeply impacting ecosystems, building databases useful to interpret bio-geophysical changes and to untangle the complexity of human-environment interactions. This further demonstrates how ‘change’ has always been inherent in ecosystems and biodiversity11,12,13, also serving as marker of the Anthropocene (Methods). The latter is here considered as the event (and not a geological era, see14) during which human agency on pristine ecosystems became dominant, its effects became permanent, and anthromes became evident15,16,17. The phase of bewilderment and helplessness that human society has gone through has led to an awareness of the need for a deeper understanding of environmental dynamics.

Palaeoecological disciplines applied to the archaeological record, including bio- and geo-archaeology, represent the most effective approach providing objective data not only on past ecological conditions, but also on historical dynamics and temporal changes18,19. Forced to read into stratified landscapes, stratigraphic units and plant records what has not been documented by written sources or documents, archaeological scientists reconstruct environmental events and human behavior otherwise buried and forgotten20. In such contexts, the history of humans is closely intertwined with that of water, soil, plants, and animals, revealing trajectories of adaptation and contrast, expansion and decline, cooperation and conflict, thus offering the opportunity to deeply understand the interaction between the environment and humankind and detangle the trajectory of anthromes. Just as medical research has multiplied efforts to develop adequate defense against the spread of human diseases, environmental research has produced new work on long-term resilience and sustainability (e.g.,21). As a measure of the persistence of systems22, resilience encompasses adaptation to adversity and can be a positive trait of ecosystems1,23,24. This better understanding of contexts helps to adopt strategies for the prevention of future environmental adversities25,26,27.

Because increasing knowledge can amplify the ethical view of the subject, this paper proposes to emphasize the uniqueness of individual sites and to incorporate a new ‘medical view’ of the conservation problem into the palaeoecological methods. Comparing the ‘sick’ environment to human illness can serve to increase the motivation to protect it, strengthening people’s awareness and commitment for Nature.

Interdisciplinarity to understand the complexity of the Pro-Anthropocene in the Mediterranean

Since the beginning of the Holocene, human action has left marks on terrestrial ecosystems7,28. In such context, the Mediterranean region can be considered an emblematic case. In prehistory, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Chalcolithic and Bronze Age populations adopted subsistence and land use strategies initially based on hunting, harvesting and wood exploitation, with the progressive introduction of cultivation and herding. Mesolithic cultures developed technical innovations at local scale whose signs do not seem to have permanently altered the local equilibrium of each ecosystem. Notwithstanding, the ecosystem exploitation strategies of Mesolithic groups preceded and were propaedeutic to Neolithic adaptive behaviour and land use. Since the late Neolithic, the exploitation of natural resources for food production progressively shifted from extensive to intensive strategies29 (Fig. 1). The increasing human pressure on the environment has led to a progressive accumulation of knowledge and impact on the environment that has prepared to the Anthropocene, a sort of Pro-Anthropocene, the prologue, or better the ‘progenote behaviour’, opening towards the present. Therefore, in this paper, the word ‘Pro-Anthropocene’ is preferred to other terms (e.g., Palaeoanthropocene30) as it evokes a long process not limited to the past as an outdated phase (Methods).

The long history of human impacts on the Mediterranean region: twelve thousand years of human-environment interactions that have shaped the landscape, from low influence (green) to high impact (red). The non-linear arrows mark the need to recover more virtuous attitudes and relationships with the environment closer to past habits. The terms ‘Anthropocene’ and ‘Pro-Anthropocene’ are intended as a cultural concept and not as epoch in Earth’s geological timeline (as discussed by International Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy in 2024); the ‘Pro-Anthropocene’ refers to the environmental-cultural conditions that prepared the onset of the Anthropocene.

With the onset of sedentary agrarian cultures, climate oscillations and human action may have had cooperative effects on vegetation and soil fertility31,32. Similarly, geomorphic processes, such as the hillslope activation and soil loss and the loosing of nutrients, may have been triggered by major climatic shifts and promoted/enhanced by concomitant human intervention since the prehistory33, thus altering the pristine equilibrium of the Critical Zone34,35. For this reason, distinguishing between anthropogenic and natural signals requires comparisons of different contexts, the analysis of different archives of proxy data, interdisciplinarity and detailed and diachronic studies of changing systems36. Mesophilous forest decline and slope instability may also be due to climatic instability or cooling. Deforestation and other land-use types (e.g., uncontrolled herding and overgrazing) contribute to vegetation and geomorphic instability. Patterns of changes generated an influence on the environment that turned into an impact, when human action persisted for a long time in the same place. This produced, for instance, forest reduction and modification in plant diversity. The dramatic fall of forest cover, the spread of cultivated species and pastures, the increase in synanthropic weeds, the intensification of erosion and slope processes, and the loss of soil are the classical surface processes and markers of human impact. The permanent marks that human activity has left on the environment and the repeated collapse of civilisations over time (albeit with different cultural trajectories in different environmental contexts) indicate that the exploitation of the environment has often been driven by a logic of predation, opportunistically rather than deliberately. The conscious idea of sustainable development is contemporary, not even fully accepted today.

Nevertheless, past cultures provided for a multifunctional land use in the Mediterranean37, and therefore less impacted but gradual and profound transformation of ecosystems occurred. In this cradle of civilisation, characterised by wide climate variability throughout the Holocene, the holistic perspective of ‘looking back while moving forward’38 is especially urgent because incipient population increases the risks from land use and consumption. The development of Mediterranean cultures over the last millennia, combined with the biological, climatic and geological diversity of habitats has created mosaic landscapes. Their distribution, along altitudinal and longitudinal gradients, makes local environmental conditions very different depending on space (location) and time (chronology).

The pollen-based uniqueness of each site

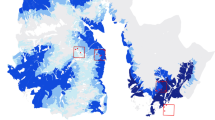

The reconstruction of past land cover at sub-continental, continental and global scales is effectively used for evaluating past land cover and climate interactions, and land use and landscape transformations over millennia. Pollen is considered among the best witnesses of past flora and vegetation, and records from lakes and similar sedimentary contexts are therefore used in the elaboration of regional and local models (within 104-105 km2 with the REVEALS model4,39,40). The LOcal Vegetation Estimates (LOVE) model is especially calibrated for estimating local vegetation composition within the relevant source area of pollen and calculated on smaller mires or bogs. Although ‘local’ is defined as being within 102 m of the depositional basin41, there are some aspects that make its application difficult in real cases. First, sites of conservation interest and requiring biodiversity studies often do not include lakes or peat bogs of adequate size. Second, most of the current interesting areas are human-disturbed lands (in plains, hills or mountains), and have hosted archaeological sites in the past that cannot be considered in these models. Archaeological sites are largely unpredictable and disrupt the concept of ‘local pollen/environment’ by shifting it from simple flight paths to the effects of cultural choices and ‘areas of influence’ in a single site. Pollen spectra from archaeological sites and their surroundings reflect the area exploited by humans and correspond to the combination of cultural and natural features of each single site. ‘On-site palynology allows us to recognise the first influence of humans even before it can be recognised in off-site sequences, and off-site sequences can allow us to determine the area of influence of a site’37: 830). Therefore, although this paper is centred on the undervalued role of the on-site records in palaeoenvironmental reconstructions and conservation, a few off-site contexts were considered as a benchmark. To test the potential biological uniqueness of sites, we expressly considered the archaeological sites and related near/off-sites, examining the floristic and plant cover from 1,208 pollen spectra. Each of the studied sites shows a forest cover ranging from ~ 20% to ~ 38%, and Anthropogenic Pollen Indicators from ~ 3% to ~ 54% (Extended Data Table 1). The number of pollen types ranges from 33 to 240, reflecting the plant diversity based on pollen morphology and marking each site’s contribution to the total biodiversity. Statistical elaborations based on β-diversity, as a means of measuring biological diversity of the sites in terms of species composition and abundance, allowed for the assessment of the biological uniqueness of each site with regard to their community composition (Local Contribution to Beta Diversity, LCBD). Consequently, this enabled the identification of the sites whose contribution to the total β-diversity was significantly higher from the others (Fig. 2; Extended Data Table 2), exploring and underlining spatial biodiversity patterns in the investigated system. Data prove similarity between on-sites and off-sites, and the persistence of biodiversity in human-influenced sites (Methods).

. Total β-diversity for on-sites and off-sites, with the relative contribution of each location to its category’s total β-diversity (Local Contribution to Beta Diversity, LCBD). Top: maps of Italy showing the geographical distribution of the considered sites for the β-diversity analysis (black dots) together with their LCBD value (circle area) and significance (colour). The zooms allow easier visualisation of sites with very close geographical location. Centre: regular bar plots reporting LCBD indices for each site with an associated p-value. The code below each bar refers to the ID code assigned to the corresponding site in the BRAIN-Botanical Record of Archaeobotany Italian Network database (https://brainplants.successoterra.net). Sites with an associated p-value < 0.05 to their LCBD are marked with an asterisk (*). Bottom: stacked bar plots showing the overall contribution of the sites grouped by macroregion (North, Centre, South/Sea) to the total β-diversity of their category (on-site/off-site). Maps were retrieved through the giscoR package version 0.6.1 (https://ropengov.github.io/giscoR/).

Implications of the biological uniqueness of a site

Despite the complexity of the variables involved, our data demonstrate that the biological uniqueness of a site can sometimes be evident just by considering past pollen spectra, i.e. the plant diversity of the past. As it is well known, the gametophytic generation has considerable specificity but hardly ever allows the same level of identification as the sporophytic generation. Palynologists adopt categories for a detailed level of identification, although it is always necessary to resort to nomenclatural harmonisation to avoid redundancies and reduce identification errors. Pollen can be identified only at a low-resolution taxonomical level with respect to plant species and sub-species, and the uniformity of anthropogenic habitats increases the risk of uniformity between sites that have been affected by anthropogenic action for a long time. Although the simplification of harmonised pollen lists might reduce differences based on past floristic composition alone, the data show that at least 20% of the sites have significant biological uniqueness, marking them as remarkably diverse with regards to their biological community (Table 1). We can infer that this is determined by a different floristic-vegetational starting point, but also by the special skills and land use choices that characterised at a certain time each patch of the different Mediterranean domain.

These results show a striking correspondence between the study of specific environmental cases and clinical cases. Just as each patient has a specific clinical history and requires customised treatment in case of disease, each threatened site may require different restoration/conservation interventions depending on its own characteristics.

The health-disease metaphor for the environment of the future

The new evolutive trajectory of ecosystems pushed by human agency – in the form of uncontrolled expansion of intensive land use, abandonment of traditional way to exploit lands and rapid climate change - often becomes an e-disease (i.e. a disease of the environment). Our vision is that, in effectively deal with environmental diseases, we must adopt a precision approach inspired by the latest developments in precision medicine. The events that could have caused an e-disease must be reconstructed in as much detail as possible to apply the correct e-therapy. Any environmental critical issue can only be addressed by applying a rigorous study protocol involving systematic and interdisciplinary research. This is rooted in the archaeological record of the human-environment nexus. All scientific expertise must work together to find sustainable solutions and to cope with current environmental challenges to finally ensure sustainable development for the next generations. For this reason, we introduce the concept of Precision Land Knowledge of the Past: the application of methods offered by palaeoenvironmental research to identify the best ‘therapeutic’ actions to safeguard biodiversity and ecosystems for the future. Rooted into local particularities, the PLKP goes beyond the state of the art, looking at the present as the result of the past.

Intervening on diseases is one of the skills that humans have always sought to gain to increase their control over life and death. Medicine has routinely adopted anamnesis as the first step to identifying the causes of a disease in each patient. Recently, the search for tailor-made solutions beyond personalised medicine unlocks the possibility of respecting the complexity of the body-mind systems to be safeguarded or, more importantly, to be cared for42. New frontiers medicine has introduced precision medicine as the optimal approach to customise therapy and successfully achieve patient’s recovery (e.g.,43; Methods). There is therefore a growing consensus44 that the same disease, but different individual genetic and phenotypic characteristics, cannot be tackled with the same shared treatment. Awareness of individual differences is increasingly gaining ground in medicine45, while it is not unanimously recognised or not practically considered in other scientific disciplines as in the case of ecological/environmental sciences. A comparable precision approach to the e-disease today is urgent as it can ‘heal’ precious ecosystems and their specific ecological traits and services.

As medicine teaches, meticulous anamnesis is required to arrive at the best differential diagnosis in environmental conservation or restoration of each site (Fig. 3). In this perspective, the Precision Land Knowledge of the Past (PLKP), like the Precision Medicine (PM), starts from the history of a specific landscape, its characteristics, and local transformations over millennia, and based of such diagnosis proposes the most effective conservation or restoration therapy. It is not appropriate to mention any specific type of intervention without the risk of generalising and contradicting the thesis of this approach. It is true that precise knowledge allows for better dosing and targeting of interventions on soil, water, or flora (e.g., ecosystems), but this approach also involves citizens as integral parts of the therapy. PLKP provides a new awareness of the value of environmental quality, making the parallelism between environmental health and human health more immediate. Involving citizens with familiar communication reminds us that all protection and conservation actions must be carried out with awareness, responsibility and respect.

The Precision Land Knowledge of the Past

Current ecosystems are far from being completely natural and, instead, they have been shaped by millennia of human action. Thus, to understand their ecological dynamics and ongoing changes, the Precision Land Knowledge of the Past - PLKP is a tool based on local resolution investigation. Thanks to its interdisciplinary approach, the PLKP responds to general and specific key research questions (Table 2) for an enhanced understanding of environment-human interaction and tailor-made landscape management strategies. Knowing the details of the environmental/vegetation development, and how cultures influenced this history, prevents ineffective interventions because correct preventive analyses avoid unnecessary actions.

Precision medicine through targeted analyses leads to customised therapies. Similarly, the PLKP consists of the targeted study of environmental problems to design solutions tailor-made for each place, elaborated considering past and present environmental evolution as a continuum of the same process. This is strategic for understanding the trajectories that led to the current situation and the directions towards a sustainable future. At the same time, it helps to assess the current state of the territory, the reasons for its current state and its vocation. The approach can be, therefore, at the base of the assessment of human-climate ecosystem dynamics for achieving sustainable land management practices. Climatic oscillations on a global scale and environmental-cultural changes acting at a local scale have continuously transformed habitats. In the Holocene, climate oscillations seem to have followed general trends towards aridity and cooling; hydroclimatic changes have been found to be synchronous with drier or cooler conditions in some records46,47. Increased aridity/cooling and vegetation changes were sometimes coincident with increased social complexity in the mid-Holocene (e.g.,48). Ecological complexity is the trait connecting all the questions posed by palaeoenvironmental research.

A PLKP tool for conducting these assessments is intended as a protocol of guidelines that examines problems, objectives and methodologies incorporating bio-geo-palaeoecology. It supports that prevention and cure are two sides of the same coin, and research must go on both fronts simultaneously. We suggest that the PLKP research protocol needs to follow three steps (Fig. 4):

-

(1)

identification of the ecological/historical problem,

-

(2)

definition of the objectives (scientific research, conservation/restoration ecology, valorisation of natural resources),

-

(3)

definition of the methodology (analysis, interdisciplinarity, dissemination).

These steps constitute the backbone of the protocol and support the subsequent phases of environmental intervention.

Such approach requires a shared analytical baseline, highly interdisciplinary and including methodologies complementary the standard ones to be applied to on-site and off-site records: Geoarchaeology, Geomorphology; Palynology, Archaeobotany; Biomolecular analyses; Statistical processing of pollen data; Databases; GIS and spatial analyses. Long-term data from bio- and geoarchaeology are strategic tools to learn in detail what environmental changes have led to today’s landscapes. The traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is also included in the PLKP workflow as a mean to improve biodiversity management and conservation practices (Methods). The protocol of Precision Land Knowledge of the Past is flexible and adaptable to different environmental, chronological and cultural context, at any archaeological site/landscape.

The results obtained from the application of the PLKP must be communicated to stakeholders (local politicians and managers), indicating the strengths and weaknesses of the site they manage or protect.

The results contribute to the debate on protection of cultural and environmental heritage (sustainable development) and for formulating models of sustainable natural resources exploitation (contribution to the solution of social problems). The points of strength of the PLKP approach are: (i) to target e-diseases with great accuracy; (ii) to identify the traditional vocation of a territory; (iii) to increase success rate or permanence of intervention effects; (iv) to mitigate the negative effects of wrong or unnecessary interventions; (v) to optimise costs and duration for sustainable development.

Future perspectives

A growing body of research shows that knowing the past does not mean wasting time and funding, but rather improving the chances of successful recovery interventions. Palaeoecological research has often emphasised the inescapable value of change and that plant associations of the past are not the same as today. Conifer-broadleaf mixed woods were more common than monospecific woods, and plant distribution shifted with suitable species following climate oscillations.

Boivin and Crowther27 explain that leveraging the past to enrich biodiversity, support conservation and improve fire management is the sustainable way to shape the Anthropocene. Morley et al.20 point out that geosciences are becoming increasingly vital for understanding unsuspected scientific questions, such as the evolution of our species. Mensing et al.49 emphasise the key role in palaeoecological interpretation of the combination of historical and archaeological sources with climatic and ecological methods; however, surprisingly only few localities ‘possess high-quality historical, archeological and high-resolution palaeoecological datasets’. There is an urgent need for such data to be collected for a larger number of locations, considering that geo-biostratigraphical analyses should be routinely prescribed by environmental administrators when planning emergency archaeology or conservation ecology projects. However, there may be limitations to modern conservation efforts in certain contexts, such as significant differences in hydro-climatic conditions, land uses that hinder restoration, absence of suitable palaeoecological contexts, or simply a lack of funding.

In the absence of such limitations, PLKP can also be usefully employed in geographical realities other than the one where we tested the approach, including regions with less extensive archaeological or palaeoecological data because the protocol is easily adaptable and is based on a combination of methods.

Therefore, a real risk exists that large actions for the protection of natural and cultural heritage – as generally planned by decision-making groups – may be inappropriate or ineffective (with high costs) due to standardised guidelines/regulations at the regional scale. On the contrary, the PLKP approach suggests that an in-depth knowledge of local environmental assets and a thorough understanding of millennial transformations are essential for long-term planning on a local scale. Building on the lessons from the past, good practices and solutions should be more and more incorporated in the environmental assessment process, such as in the ‘Guidelines for conducting integrated environmental assessment’ by the UN Environment Programme.

In this way, the protection and preservation of the environment and its (past to future) evolution become effective respecting its unique bio-geo-cultural diversity. This is ultimately the result of a long term, multi-scalar and multi-factor process. Complexity and potential uniqueness of each site show that sustainable solutions should not be the same everywhere and adopting the PLKP approach helps the identification of the best solution for each local situation. While enabling sustainable tailor-made environment therapy, PLKP strengthens awareness and commitment for Nature, and improves empathy and connectedness to Nature. Stimulating empathy has important effects on both environmental and human health. According to Di Fabio & Kenny50, in fact, ‘fostering empathy and connection to nature could represent promising foci for a range of preventive interventions in the workplace and beyond that would address the urgent issue of environmental sustainability’.

Looking at the Holocene evolution of ecosystems, PLKP may furnish solutions to prevent an uncontrolled land-use expansion, explain/prevent the effects of the abandonment of traditional ways for landscape management, or mitigate local effects of rapid climate changes. Future conservation or restoration planning must draw based on new data provided by palaeosciences7. Not just ‘a history of the land’, but a deep consideration of the traits, vocation and potential development of each land.

Methods

One word many meanings: specific definitions for an unambiguous connotation

The meaning of some of the terms here adopted may be ambiguous or slightly different in studies from different disciplines, and therefore the definitions followed in this paper are reported below.

Anthropocene = both scientifically and philosophically (e.g.,51,52), it is a cultural concept describing the current time in which humans act as a key force permanently impacting on the environment, accelerating climate change and biodiversity loss. First used in 2000 as a human-dominated geological epoch53, this term focused on anthropic influenced habitats and novel ecosystems, in which human impacts are at least as important as natural processes54. The definition as the most recent geological epoch, either after or within the Holocene, has been currently rejected by the SQS (Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy55), regarded as a broad process or an event in geological history, but not as a distinct break in time14.

Pro-Anthropocene = environmental-cultural precondition that – after the long-term intensification of human impact over time – led to the onset of the Anthropocene in the industrial era. Biologically, the suffix ‘Pro’ indicates a form/state that precedes and often gives rise to another (the one indicated by the second element) considered definitive (e.g., proembryo, promeristemio, etc.;56,57). ‘Pro’ is used, for example, in biology (e.g., Prokaryotes - i.e. before the nucleus; Progenotes - i.e. before the organisms), and specifically in evolutionary botany to signal groups that already possess characters that will be retained and are visible in the groups living today (e.g., the photosynthetic apparatus in Prochlorophyceae, or the homoxylous wood in the Progymnospermae). Similarly, the progressive accumulation of knowledge and impact on the environment due to the increasing human pressure that prepared for the Anthropocene could be compared to the ‘progenote behaviour’. Progenotes are the basic organisation of very different cellular models, just as the Pro-Anthropocene is an adaptation to different models leading to the present Anthropocene. In this paper it means the progressive acquisition of cultural and skills and technology and the accumulation of anthropogenic effects on environment that gave rise to the Anthropocene.

Anthromes = the krasis of the two words ‘anthropogenic biomes’ was coined by Ellis & Ramankutty58, who identified the biomes highly influenced by humans as mosaics of settlements, agriculture, forests and other land uses and land covers. This prevents a general ecological understanding of ‘human–eco-system interactions’.

Consilience = the synergy of natural sciences and humanities59,60.

Long-term = the time significantly longer than that of a few human generations (e.g.,61).

On-site = an archaeological site corresponding to an ancient settlement or location clearly affected by past human activities.

Off-site = a context outside the major archaeological settlement that can be influenced by human presence.

Personalised medicine = according to William Osler (1849–1919), who was a diagnostician, a clinician and a medicine professor and established a patient-centered approach: "It is much more important to know what sort of patient the disease has than what sort of disease a patient has’’. Physicians have always practiced personalised medicine, in the sense of using professional experience to adapt the best literature data to the individual patient. Medical science, however, has adopted a predominantly population-based approach, favoring the reaction of the ‘average patient’ over the particular case, especially in the field of pharmacology. The results have been positive overall, but in detail every day many people take medication that is little or not at all effective for their disease62,63,64.

Precision medicine = originally coined in the oncology field, this approach aims to analyse all dimensions of the patient to ‘tailor’ the treatment to individual characteristics65. It was possible thanks to the enormous technical advances in molecular biology, which made it possible to objectify and quantify the heterogeneous nature of most diseases and phenotypic variability of individuals at the level of genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics, the so-called ‘panomics’63.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) = holistic concept expressing the bio-cultural links between people and nature; focused on human-environment relationships in local ecosystems, the study of TEK started from ethnobiology and then considered the understanding of adaptation and ecological processes. The use of this term was established mainly through the work of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) working group66. In our paper, we are referring to the definition of TEK given by Berkes and colleagues67 as ‘a cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment’.

Site selection

We selected 43 Italian sites, including 32 on-sites and 11 off-sites, with archaeopalynological analyses included in the BRAIN database (analysed by the LPP team;10). On-sites (archaeological sites) provide intrinsic evidence of past land use and human impact, at the core of features that must be considered to assess the current state and transformations in environmentally important contexts (e.g.,68). The area of investigation is Italy, guardian of Mediterranean biodiversity, rich in plant species, endemics and habitats. More than 50% of plant species and 30% of animal species of Community Conservation Interest are Italian endemics. Italy has been selected thanks to the availability of the BRAIN database and because it is a peninsula stretching in the Mediterranean region encompassing a high variability of ecosystems and being settled and exploited since the early prehistory. Sites were distributed in 10 regions on northern (Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Trentino-Alto Adige, Veneto, Emilia-Romagna, and Repubblica di San Marino), central (Toscana and Lazio) and southern Italy (Basilicata, Sicilia, and Adriatic Sea), according to the database ID. To study the similarity/diversity between past floristic lists, pollen spectra obtained from archaeological sites were only considered if at least 30 pollen taxa were identified. This made it possible to exclude data affected by selective pollen degradation, a problem that may be common in samples from floors and other potentially oxidised/carbonised spots on archaeological sites69. In general, not all data obtained on site are of the same quality, as taphonomy has a certain influence and can alter them. Modern pollen samples (surface soils, moss pollsters or top samples from sediment cores) were excluded from this study.

Data elaboration

Pollen taxa standardisation

To enable data processing, the lists of pollen taxa from the original works were standardised according to the keys by Moore et al.70, Beug71 and other authors. Identifications at species level follows the botanical nomenclature used by APG IV72 and The Plant List Version 1.173. The local flora defines the nomenclatural standardisation of all pollen taxa in the sequences, mainly using a critical bottom-up harmonisation according to Birks et al.74.

Data elaboration for local contribution to beta diversity (LCBD)

β-diversity, intended as the variation in species composition on a geographical area75,76, was assessed for 32 fossil pollen datasets from on-sites and for 11 fossil pollen datasets from off-sites. Due to pollen identification concerns, β-diversity is intended as the variation in pollen taxa composition among the considered locations.

A presence-absence matrix was separately computed for on-sites data and for off-sites data, with p species arranged in columns and n locations arranged in rows. Both the matrices were then transformed in distance matrices using the binary form of Jaccard’s similarity coefficient77. These indices are considered suitable for β-diversity assessment and have desirable properties for the purpose of this study78. Then, the total β-diversity (BDTotal) for each matrix was computed as Var(Y), with Y being the matrices, following78,79. The maximum BDTotal value obtainable when using Jaccard-transformed matrices is 0.577.

After calculating BDTotal, Local Contribution to Beta Diversity (LCBD;78) was assessed for each on-site and off-site location. LCBD is the relative contribution of a location to the total β-diversity, and ecologically represents the degree of uniqueness of its biotic community78. LCBD for each location was computed following Legendre & De Cáceres78, and the statistical significance of each LCBD index was assessed via random independent permutations (n = 9999) within the matrices’ columns, testing H0 that the pollen taxa are distributed at random and independently of one another among the sites78 with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Due to each LCBD value being a fraction of the total β-diversity of its site’s respective category (on-site/off-site), each value was multiplied by 100 for clarity and data visualisation in plots.

All statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.3.380 and the adespatial package version 0.3–2481. Figure 2 plots, depicting the results of the statistical analyses, were produced with R version 4.3.380. and the ggplot2 package82.

The statistical significance of each site’s contribution to the total β-diversity was assessed according to the null hypothesis that pollen taxa were distributed randomly and independently of one another among the sites (Fig. 2). Thus, a non-significant contribution to the total β-diversity does not suggest a poorly biodiversity community per se, but rather indicates a community higher in generalist or ubiquitous plant species, therefore more likely to be obtained through data randomisation. As a consequence, sites with a non-significant LCBD do not add much to the total β-diversity when compared to sites that significantly contribute to it instead. Sites with a non-significant LCBD keep some degree of uniqueness, not only in a biological sense because of their communities never being perfectly identical, but also owing to each’s own peculiar chrono-cultural, geological and geographical setting. Moreover, statistical processing of the data on the plant communities of the sites shows that the total β-diversity is not much lower at the off-sites than at the on-sites, even if the off-site datasets are almost half of the on-sites. This suggests considerable biological diversity in communities of the analysed off-sites. As on-sites bear the human influence on biodiversity, the results show a clear reflection of past human presence heavily influencing native plant communities in on-sites. Nonetheless, a similar proportion of sites among the two categories (on-sites/off-sites) had a significant LCBD, and the difference between significant and non-significant LCBD values is never remarkably high. This highlights the presence, value and persistence of biological uniqueness in human-influenced locations, as well, and shows how biodiversity flourishes even in a past semi- or non-natural (anthropogenic) environment, further underlining the importance of considering every single location as a potential biodiversity host.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are provided in the Supplementary information.

References

Malhi, Y. et al. Climate change and ecosystems: Threats, opportunities and solutions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 375, 20190104 (2020).

Hodel, F. H., Behr, D. M., Cozzi, G. & Ozgul, A. A hierarchical approach for estimating state-specific mortality and state transition in dispersing animals with incomplete death records. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 1074–1091 (2023).

Pearce, E. A. et al. Substantial light woodland and open vegetation characterized the temperate forest biome before homo sapiens. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi9135 (2023).

Githumbi, E. et al. European pollen-based REVEALS land-cover reconstructions for the holocene: Methodology, mapping and potentials. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 14, 1581–1619 (2022).

Serge, M. A. et al. Testing the effect of relative pollen productivity on the REVEALS model: A validated reconstruction of Europe-Wide holocene vegetation. Land 12, 986 (2023).

Froyd, C. A. & Willis, K. J. Emerging issues in biodiversity & conservation management: The need for a palaeoecological perspective. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 1723–1732 (2008).

Stephens, L. et al. Archaeological assessment reveals Earth’s early transformation through land use. Science 365, 897–902 (2019).

Morrison, K. D. et al. Mapping past human land use using archaeological data: A new classification for global land use synthesis and data harmonization. PLoS ONE. 16, e0246662 (2021).

de Vareilles, A., Pelling, R., Woodbridge, J. & Fyfe, R. Archaeology and agriculture: Plants, people, and past land-use. TREE 36, P943–954 (2021).

Mercuri, A. M. et al. BRAIN—Holocene archaeo-data for assessing plant-cultural diversity in Italy and other mediterranean regions. Sci. Data. 11, 520 (2024).

Steffen, W. et al. The emergence and evolution of Earth system science. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 54–63 (2020).

Capotondi, L. et al. Using the past to envisage a better future: The approach of a quaternary scientist. Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 34, 257–275 (2021).

McNeely, J. A. & Nature COVID-19: The pandemic, the environment, and the way ahead. Ambio 50, 767–781 (2021).

Gibbard, P. et al. The anthropocene as an event, not an epoch. J. Quat. Sci. 37, 395–399 (2022).

Few, R., Morchain, D., Spear, D., Mensah, A. & Bendapudi, R. Transformation, adaptation and development: Relating concepts to practice. Palgrave Commun. 3, 17092 (2017).

Malhi, Y. The concept of the anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 42, 77–104 (2017).

Ellis, E. C. The anthropocene condition: Evolving through social–ecological transformations. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 379, 202202552024 (2024).

Bjune, A. E., Grytnes, J. A., Jenks, C. R., Telford, R. J. & Vandvik, V. Is palaeoecology a ‘special branch’ of ecology? Holocene 25, 17–24 (2015).

Birks, H. J. B., Birks, H. H. & Ammann, B. The fourth dimension of vegetation. Science 354, 412–413 (2016).

Morley, M. W. et al. Why the geosciences are becoming increasingly vital to the interpretation of the human evolutionary record. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1971–1977 (2023).

Mercuri, A. M., Florenzano, A. & Clò, E. Sustainability in the Neolithic and the Bronze Age through the lens of archaeobotany. In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Sustainability (Cham, Palgrave Macmillan, 2023). ISBN 978-3-031-01948-7. (2022).

Holling, C. S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 4, 1–23 (1973).

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D. & Becker, B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child. Dev. 71, 543–562 (2000).

Folke, C. et al. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 15, 20 (2010).

Boivin, N. L. et al. Ecological consequences of human niche construction: Examining long-term anthropogenic shaping of global species distributions. PNAS 113, 6388–6396 (2016).

Whitlock, C., Colombaroli, D., Conedera, M. & Tinner, W. Land-use history as a guide for forest conservation and management. Conserv. Biol. 32, 84–97 (2017).

Boivin, N. & Crowther, A. Mobilizing the past to shape a better anthropocene. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 273–284 (2021).

Roberts, P. et al. Uncovering the Multibiome environmental and Earth system legacies of past human societies. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 49, (2024). 23.1–23.30.

Arena, F., Gualdi-Russo, E., Olsen, J., Philippsen, B. & Mannino, M. A. New data on agro-pastoral diets in Southern Italy from the neolithic to the bronze age. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 12, 245 (2020).

Foley, S. F. et al. The Palaeoanthropocene – The beginnings of anthropogenic environmental change. Anthropocene 3, 83–88 (2013).

López Sáez, J. A. et al. Vegetation history, climate and human impact in the Spanish central system over the last 9000 years. Quat. Int. 353, 98–122 (2014).

Rick, T. et al. Human-environmental interactions in mediterranean climate regions from the pleistocene to the anthropocene. Anthropocene 31, 100253 (2020).

Cremaschi, M. When did the anthropocene begin? A Geoarchaeological approach to Deciphering the consequences of human activity in pre-protohistoric times: Selected cases from the Po plain (northern Italy). Rend. Fis. Acc. Lincei. 25, 101–112 (2014).

Hooke, J. M. Human impacts on fluvial systems in the mediterranean region. Geomorphology 79, 311–335 (2006).

Regattieri, E. et al. Holocene critical zone dynamics in an alpine catchment inferred from a speleothem multiproxy record: Disentangling climate and human influences. Sci. Rep. 9, 17829 (2019).

Sadori, L., Aranbarri, J. & Masi, A. Pollen records, postglacial | Southern Europe. Ref. Module Earth Syst. Environ. (2023).

Mercuri, A. M. et al. From influence to impact: The multifunctional land use in mediterranean prehistory emerging from palynology of archaeological sites (8.0-2.8 ka BP). Holocene 29, 830–846 (2019).

Desjardins, S. P. A., Friesen, T. M. & Jordan, P. Looking back while moving forward: How past responses to climate change can inform future adaptation and mitigation strategies in the Arctic. Quat Int. 549, 239–248 (2020).

Sugita, S. Theory of quantitative reconstruction of vegetation I: Pollen from large sites REVEALS regional vegetation 1210 composition. Holocene 17, 229–241 (2007).

Sugita, S. Theory of quantitative reconstruction of vegetation II: All you need is LOVE. Holocene 17, 243–257 (2007).

Jacobson, G. L. & Bradshaw R.H.W. The selection of sites for paleovegetational studies. Quat. Res. (1981).

Saeed, R. F. et al. Targeted therapy and personalized medicine. Cancer Treat. Res. 185, 177–205 (2023).

Hodson, R. Precision medicine. Nature 537, S49 (2016).

Uffelmann, E. et al. Genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers. 1, 59 (2021).

Vicente, A. M., Ballensiefen, W. & Jönsson, J. -I. How personalised medicine will transform healthcare by 2030: The icpermed vision. J. Transl. Med. 18, 180 (2020).

Di Rita, F. et al. Holocene forest dynamics in central and Western mediterranean: Periodicity, spatio-temporal patterns and climate influence. Sci. Rep. 8, 8929 (2018).

Cramer, W., Guiot, J. & Marini, K. MedECC - Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin – Current Situation and Risks for the Future. First Mediterranean Assessment Report (Union for the Mediterranean, Plan Bleu, UNEP/MAP, Marseille, France, (2020).

Regattieri, E. et al. Neolithic hydroclimatic change and water resources exploitation in the fertile crescent. Sci. Rep. 13, 45 (2023).

Mensing, S. A. et al. Historical ecology reveals landscape transformation coincident with cultural development in central Italy since the Roman period. Sci. Rep. 8, 2138 (2018).

Di Fabio, A. & Kenny, M. E. Connectedness to nature, personality traits and empathy from a sustainability perspective. Curr. Psychol. 40, 1095–1106 (2021).

Zalasiewicz et al. What should the anthropocene mean? Nature 632, 980–984 (2024).

Aime, M., Favole, A. & Remotti, F. Il Mondo Che Avrete. Virus, Antropocene, Rivoluzione (Torino, UTET De Agostini, 2020).

Crutzen, P. J. Geology of mankind. Nature 415, 23 (2002).

Corlett, R. T. The anthropocene concept in ecology and conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 36–41 (2015).

Witze, A. Geologists reject the anthropocene as Earth’s new epoch – after 15 years of debate. Nature 627, 249–250 (2024).

Treccani - https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/pro-2_(Sinonimi-e-Contrari)/?search=pro-%C2%B2%2F.

Etymonline - https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=pro (n.3).

Ellis, E. C. & Ramankutty, N. Putting people in the map: Anthropogenic biomes of the world. Front. Ecol. Environ. 6, 439–447 (2008).

Izdebski, A. et al. Realising consilience: How better communication between archaeologists, historians and natural scientists can transform the study of past climate change in the mediterranean. Quat Sci. Rev. 136, 5–22 (2016).

Chiotis, E. Climate Changes in the Holocene: Impacts and Human Adaptation (CRC, 2019).

Willis, K. J. & Birks, H. J. What is natural? The need for a long-term perspective in biodiversity conservation. Science 314, 1261–1265 (2006).

Schork, N. J. Personalized medicine. Time for one-person trials. Nature 520, 609–611 (2015).

Collecchia, G. Dalla medicina personalizzata Alla medicina Di precisione. IsF 41, 19–22 (2017).

Roden, D. M. et al. Development of a large-scale de-identified DNA biobank to enable personalized medicine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 84, 362–369 (2008).

Schulte, D. Tailor-made and standardized therapy: Complementary tasks in behavior therapy a contrarian view. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 27, 119–126 (1996).

Williams, N. M. & Baines, G. Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Wisdom for Sustainable Development (Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies (Australian National University, 1993).

Berkes, F., Colding, J. & Folke, C. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 10, 1251–1262 (2000).

Cremaschi, M. et al. Climate change versus land management in the Po plain (Northern Italy) during the bronze age: new insights from the VP/VG sequence of the Terramara Santa Rosa Di Poviglio. Quat Sci. Rev. 136, 153–172 (2016).

Dimbleby, G. W. The Palynology of Archaeological Sites (Academic, 1985).

Moore, P. D., Webb, J. A. & Collins, M. E. Pollen Analysis 2nd edn (Oxford, Blackwell Scientific, 1991).

Beug, H. J. Leitfaden Der Pollenbestimmung Für Mitteleuropa Und Angrenzende Gebiete (München, Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, 2015).

The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 181, 1–20 (2016).

The Plant List. Version 1.1. (2013). http://www.theplantlist.org/

Birks, H. J. B. et al. Approaches to pollen taxonomic harmonisation in quaternary palynology. Rev. Palaeobot Palynol. 319, 104989 (2023).

Whittaker, R. H. Vegetation of the Siskiyou mountains, Oregon and California. Ecol. Monogr. 30, 279–338 (1960).

Whittaker, R. H. Evolution and measurement of species diversity. Taxon 21, 213–251 (1972).

Jaccard, P. Contribution Au problème de l’immigration post-glaciaire de La Flore alpine. Bull. De La. Société Vaudoise Des. Sci. Nat. 36, 87–130 (1900).

Legendre, P. & De Cáceres, M. Beta diversity as the variance of community data: Dissimilarity coefficients and partitioning. Ecol. Lett. 16, 951–963 (2013).

Legendre, P. & Legendre, L. Numerical Ecology, 3rd English edition Elsevier Science BV, Amsterdam, ISBN 978-0-444-53868-0. (2012).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2024).

Dray, S. et al. adespatial: Multivariate Multiscale Spatial Analysis (2024).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag New York, ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was developed in the framework of activity promoted by two actions of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP): Mission 4, Component 2 Investment 1.4 - Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree 363 n.3175 of 18 December 2021 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU. Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP E93C22001090001, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center – NBFC”; Mission 4, Component 2 Investment 1.3 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU, Project title “Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Sustainable Society (CHANGES)”. The study is part of a PhD project started in 2022 in the frame of PON actions (IV.5 «Tematiche Green») and within the activities supported by the SUCCESSO-TERRA Project, financed by MIUR (grant no. PRIN20158KBLNB). Additional support is from the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) through the project “Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2023–2027” awarded to the Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra “A. Desio” of the Università degli Studi di Milano (WP3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.M. and A.Z. coordinated the study. A.M.M. and A.F. wrote the draft manuscript. E.C., J.Z., A.Z. and M.C. checked the text for consistency. L.B. handled the elaboration and statistical processing of data. A.F., E.C., J.Z. and L.B. prepared the figures and edited the reference section. All authors provided substantial input into ideas and text and commented on draft manuscripts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mercuri, A.M., Florenzano, A., Clò, E. et al. The precision land knowledge of the past enables tailor-made environment therapy and empathy for nature. Sci Rep 15, 12587 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97372-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97372-x