Abstract

Neuroticism (NT) is a fundamental personality trait and a major risk factor for both the onset and persistence of depression and anxiety disorders. Although NT involves alterations in emotion–cognition interaction, its precise neural mechanism remains insufficiently understood. Leveraging the word-face Stroop task, we examined neural circuits engaged during emotional conflict using a relatively large sample that exhibited a wide range of NT levels. Generalized psychophysiological interaction (gPPI) analyses revealed that individuals with high NT were characterized by decreased functional connectivity between the anterior midcingulate cortex (aMCC) and both the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and the left amygdala. None of these regions showed modulated brain activation by NT. Our findings suggest that the neural substrates of NT can be better characterized by reduced top-down aMCC-amygdala regulation as well as inefficient communication within the dorsal cognitive system (aMCC-dlPFC), rather than changes in brain activation in isolated regions. These observations offer valuable insights into the neural markers of vulnerability to mood and anxiety disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuroticism (NT) is one of the core personality dimensions, characterized by a propensity to experience frequent, intense, and prolonged negative emotions1,2. When extreme, it confers elevated risk for a variety of adverse outcomes, including psychological disorders3,4,5. A recent meta-analysis6 confirmed robust prospective associations between NT and symptoms/diagnoses of depression and anxiety (d = 0.5–0.7), which remained significant even after adjusting for baseline symptoms (d = 0.3). Behaviorally, individuals with high NT tend to allocate excessive attention to negative information and show greater stress reactivity3,7. Although these characteristics are assumed to reflect alterations in emotion–cognition interactions, the precise neural mechanisms underlying individual differences in NT remain unclear.

Traditionally, neuroscientific studies have focused on the link between NT and the amygdala, given its crucial role in prioritizing the processing of salient, especially negative, cues8. Brain imaging studies have demonstrated that individuals with high NT show greater amygdala responses to negative images9,10 and conditioned threat cues11 compared to those with low NT. However, several studies failed to replicate these findings12,13,14, suggesting that NT may instead reflect a failure in neural systems responsible for top-down cognitive control during the processing of negative stimuli. Indeed, moving beyond the amygdala, several studies have demonstrated associations between NT and changes in brain activation in frontocortical regions involved in top-down cognitive control, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and anterior midcingulate cortex (aMCC), even in the absence of emotional stimuli15,16,17,18. Together, these observations suggest that the neural model of NT may be better conceptualized by considering its impact on both bottom-up emotion processing and top-down control processes. Given the reciprocal interaction between these processes19,20,21,22, it is imperative to elucidate how NT modulates their integration and interaction.

The aMCC, also known as the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), is a key hub for the integration of bottom-up emotion and top-down cognitive processes23,24,25. Anatomically, it is uniquely positioned, with connections to top-down control regions (e.g., dlPFC) and bottom-up emotion processing regions (e.g., amygdala). Functionally, the aMCC is involved in detecting and resolving cognitive conflict by closely communicating with the dlPFC for higher-order executive control26,27,28. It also plays a critical role in emotion processing, such as encoding negative feelings, aversive learning, and emotion regulation29,30. Notably, the inhibitory control function of the aMCC over the amygdala has been emphasized22,31. For example, Pezawas et al.32 showed an inverse association between aMCC and amygdala activation when processing negative stimuli. Other studies have shown increased functional connectivity (FC) between the aMCC and amygdala during emotional distraction33 or recovery from acute stress34. Considering its significant role in cognition-emotion interactions, examining how NT modulates aMCC activity and its FC with other regions is essential.

The word-face Stroop task35, an emotional conflict task, provides a unique avenue for exploring emotion–cognition interactions as it requires cognitive control over emotionally salient distractors (e.g., faces) whose valence conflicts with that of the target (e.g., words). The task robustly activates the aMCC29,33,35,36 as well as bilateral prefrontal regions37. However, only a limited number of fMRI studies have examined the effect of NT during the emotional conflict task, showing that NT is associated with increased activation in the aMCC37 or the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala38. These studies, however, were limited by small sample sizes and did not examine how NT modulates FC between the aMCC and other regions critical for cognitive control and emotion processing. As FC reflects the temporal communication between brain regions39,40, it can provide a comprehensive understanding of how NT influences emotion–cognition interactions.

To address these gaps, the present study employed the emotional conflict task in a relatively large sample with a broad spectrum of NT levels. We investigated how NT modulates aMCC activity and its FC with the dlPFC and the amygdala–key regions for cognitive control and emotion processing, respectively.

Method

Overview

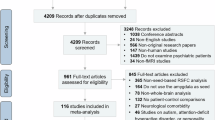

As part of an ongoing longitudinal study examining the etiological mechanisms underlying risk for depression and anxiety disorders, we screened 3281 young adults (76% female; age: M = 22.07 years, SD = 2.03 years) using measures of NT41,42,43. A stratified sampling method was employed to ensure representation across a wide range of NT levels. Screening data were categorized into three strata (low, middle, and high NT), and individuals meeting the inclusion criteria were independently and randomly selected from each group. Through this sampling approach, we captured a broad range of dimensional NT scores. The NT distributions for both the full screening sample and the final sample are presented in Fig. 1a.

A total of 85 subjects were recruited. The target sample size was selected to ensure acceptable power and precision while considering resource constraints44,45. Of these, 20 were excluded from analyses for the following reasons: voluntary withdrawal (N = 1), technical issues (N = 5), neurological findings (N = 2), distortion correction error (N = 1), excessive motion (N = 9; see criteria below), and non-compliance (N = 2). Subjects were excluded for excessive motion if their scans with motion outliers (i.e., framewise displacement > 0.5 mm) exceeded 10% of the total volumes. This resulted in a final sample of 65 subjects (83% female; mean age = 22.26 years).

All subjects were Korean young adults under 25 years old residing in the Seoul metropolitan area. Subjects reported the absence of current internalizing disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder) as well as lifetime neurological or alcohol/substance-related problems. Additionally, all subjects reported the absence of suicidal ideation, psychiatric treatment, or psychiatric medicine use. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea, and subjects provided informed written consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Neuroticism trait (NT) questionnaires

Similar to the methodology used by Griffith et al.43, NT was measured using a set of questionnaires, including the NT subscales from the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (12 items)2,46, the Big Five Inventory (12 items)47, and the Behavioral Inhibition Scale (7 items)48. Composite NT scores were calculated by averaging the standardized scores from each measure42.

Experimental design

Stimuli

Ninety words (30 negative, 30 positive, and 30 neutral) were selected from the Korean Affect Word List49. Supplementary Table 1 presents the mean ratings for valence, arousal, and frequency for each word type. ANOVA revealed a significant valence effect, F(2, 87) = 1665.82, p < 0.001. Post-hoc paired t-tests showed that negative words had significantly lower valence than neutral words (p < 0.001), and neutral words had significantly lower valence than positive words (p < 0.001). A significant arousal effect was also confirmed, F(2, 87) = 40.19, p < 0.001. Post-hoc paired t-tests revealed that the mean arousal of negative words was significantly higher than that of both neutral and happy words (ps < 0.001). The arousal of neutral words was not significantly different from that of happy words (p = 0.25). All words were two-syllable Korean words, and their frequency was balanced across categories. Sixty face pictures (20 fear, 20 happy, and 20 neutral) were selected from the Racially Diverse Affective Expression (RADIATE) stimulus set50. This stimuli set is openly accessible and widely used in research, available on the ABCD Study website: https://abcdstudy.org/scientists/abcd-fmri-tasks-and-tools/. The face stimuli were balanced for both gender and race.

Word-Face Stroop task

Subjects completed the modified word-face Stroop task35 during fMRI scanning. This task creates emotional conflict by presenting affective words (targets) overlaid on emotionally incongruent or congruent facial expressions (distractors). Incongruent pairings require inhibitory processes to override task-irrelevant emotional information. Subjects were instructed to indicate the valence of the word (positive, negative, or neutral) regardless of the facial expression (Fig. 1b).

The task consisted of three conditions: emotionally incongruent (EI), emotionally congruent (EC), and neutral (N). EI stimuli paired a randomly selected positive or negative word with a face of opposing valence (e.g., the word “pain” on a happy face). EC stimuli paired a randomly selected positive or negative word with a face of matching valence (e.g., the word “pleasure” on a happy face). N stimuli paired a neutral word with a neutral face (e.g., the word “table” on a neutral face).

Each condition block contained 10 trials. In EI and EC blocks, stimuli were presented for 1.5 s, with inter-stimulus intervals (ISIs) varying randomly from 2 to 4 s (2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4 s), during which a central fixation cross was displayed. In N blocks, each trial lasted 1.5 s and was followed by a central fixation cross for 3 s. After the presentation of three blocks, a 21-s rest period (fixation cross) was displayed. The block order was pseudo-randomized, ensuring that N blocks were always interspersed between EI and EC blocks. For the analyses, only data from EI and EC conditions were included.

Study overview. (a) Sample distribution of NT scores. To ensure a broad spectrum of NT, participants were selectively recruited from a pool of 3281 prescreened individuals. The top panels display the NT distribution as histograms for the screening sample (left, N = 3281) and the final fMRI sample (right, N = 65). NT neuroticism, SD standard deviation. (b) Experimental paradigm of the modified word-face Stroop task. Emotionally congruent, emotionally incongruent, and neutral blocks are repeated six times (a total of 18 blocks). In the EC and EI blocks, stimuli were displayed for 1.5 s, with inter-stimulus intervals (ISIs) randomly varying between 2 to 4 s, during which a central fixation cross was presented. In the N blocks, stimuli were presented for 1.5 s, followed by a 3-s display of a central fixation cross. EC emotionally congruent, EI emotionally incongruent, N neutral.

MRI data acquisition

MRI data were acquired using a Siemens MAGNETOM VIDA 3-tesla scanner (32-channel head coil). T1-weighted anatomical images were acquired using a magnetization-prepared rapid-acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR = 2300 ms, TE = 2.26 ms, flip angle = 8 degrees, field of view = 256 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, voxel size 1 × 1 × 1 mm3). Enhanced resolution was achieved using a multiband EPI sequence (multiband acceleration = 3, TR = 1500 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 80 degrees, field of view = 220 mm, matrix = 110 × 110, 69 transversal slices, interleaved slice acquisition, voxel size 2 × 2 × 2 mm3, 594 volumes). In addition, for distortion correction, 10 EPI images with reversed (i.e., posterior to anterior) phase encoding direction as well as double-echo gradient EPI images were collected (TR = 672 ms, TE 1 = 4.92 ms, TE 2 = 7.38 ms, flip angle = 60 degrees, field of view = 220 mm, matrix = 110 × 110, 69 transversal slices, voxel size 2 × 2 × 2 mm3) to generate two magnitude images and a single phase difference image.

Image preprocessing

Data preprocessing was performed using fMRIPrep 22.1.151 [RRID: SCR_016216], which relies on Nipype 1.8.552 [RRID: SCR_002502] (see Supplementary Material for further details).

Functional data preprocessing

First, a reference volume and its skull-stripped version were generated using a custom methodology in fMRIPrep. Head-motion parameters with respect to the BOLD reference (transformation matrices, and six corresponding rotation and translation parameters) were estimated prior to any spatiotemporal filtering using mcflirt53 (FSL 6.0.5.1:57b01774). The estimated fieldmap was then aligned to the target EPI (echo-planar imaging) reference run using rigid registration, and the field coefficients were applied to the reference EPI. Slice-time correction for BOLD runs was performed using 3dTshift from AFNI54 [RRID: SCR_005927]. The BOLD reference was then co-registered to the T1w reference using bbregister (FreeSurfer), which employs boundary-based registration55. Co-registration was configured with six degrees of freedom. The BOLD time-series were subsequently resampled into standard space, producing a preprocessed BOLD run in MNI152NLin6Asym space. Automatic removal of motion artifacts using independent component analysis (ICA-AROMA)56 was performed on the preprocessed BOLD on MNI space time-series after removal of non-steady state volumes and spatial smoothing with an isotropic, Gaussian kernel of 6 mm FWHM (full-width half-maximum). Corresponding “non-aggressively” denoised runs were generated after the smoothing process.

Statistical analyses

Behavioral analysis

Paired t-tests were conducted to examine differences in response time (RT) and error rates between the EI and EC trials. Correlation analyses were performed to assess associations between NT and behavioral measures (RT, error rates).

fMRI analysis

(1) BOLD fMRI data analysis

Preprocessed images were analyzed using statistical parametric mapping (SPM12) software (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). At the subject-level, separate predictors were entered for EI, EC, and N conditions and convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF). A high-pass filter (cutoff: 128 s) was applied. EPI volumes with excessive framewise displacement (FD > 0.5 mm) and non-steady outliers were regressed out. Contrast images (EI vs. EC) were generated for each subject and entered into a second-level random-effects model. Significance was assessed using FDR correction (q < 0.05, whole-brain).

To examine whether and how NT modulates brain activation in a priori regions (i.e., aMCC, dlPFC, and amygdala), region of interest (ROI) analysis was conducted. The selection of ROIs was based on prior research indicating their association with NT in the context of emotion processing and top-down cognitive control33,35,36,37,38. To define the aMCC mask, we derived a map from Neurosynth57 by entering “cognitive control” as a search term. Next, this map was overlaid onto the task effect map to delineate a 6-mm sphere centered around the peak coordinate within the MCC, supplementary motor area and medial frontal cortex atlas from Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas 358. Although our aMCC mask (peak MNI coordinate: x = − 6, y = 18, z = 46) was located on the boundary between aMCC and pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA) and extending to dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), this region has been frequently referred to as dACC and activation of this area was related to both cognitive control and emotion processing59,60,61. In a similar manner, to define the bilateral dlPFC mask, we overlaid the cognitive control associated map from Neurosynth onto the task effect map to delineate 6-mm spheres centered around the peak coordinate within the bilateral dlPFC (left peak MNI voxel coordinate: x = − 52, y = 18, z = 32; right peak MNI voxel coordinate: x = 46, y = 26, z = 32), and nonbrain voxels were excluded. For the bilateral amygdala mask, we generated the mask from the FSL Harvard-Oxford probabilistic atlas. Mean contrast values in each ROI (aMCC, bilateral dlPFC, and bilateral amygdala) were extracted from the individual EI vs. EC contrast maps. In the case of the dlPFC and the amygdala, the contrast values extracted from left and right masks were averaged. Correlations between NT and mean contrast values from each ROI were calculated. For exploratory purposes, the association between brain activity during emotional conflict (EI vs. EC) and individual differences in NT was tested with multiple regression in whole-brain analysis (FDR q < 0.05, whole-brain corrected).

(2) Generalized Psychophysiological interaction (gPPI) analysis

Using the CONN toolbox62 release 22.a [RRID SCR_009550], seed-based FC analysis was conducted using the aMCC as the seed region. Images were denoised by regressing out confounding effects characterized by task effects and their first order derivates, motion spike regressors (FD > 0.05 mm), and non-steady outliers, and high-pass filtered (> 0.008 Hz). Following standard gPPI procedures63, the first-level general linear models for each subject were constructed using seed BOLD signals as the physiological factors, boxcar signals representing each task condition (EI, EC, and N) convolved with a hemodynamic response function (HRF) as the psychological factors, and the product of the two as the psychophysiological interaction (PPI) terms. To examine differences between conditions, EI vs. EC PPI contrasts were generated at the subject level.

FC between the aMCC and bilateral dlPFC/amygdala was examined for associations with NT. After extracting individual PPI mean contrast values (EI vs. EC) from the 4 ROIs (L/R dlPFC, L/R amygdala), correlation analyses were performed with NT. For exploratory purposes, whole-brain gPPI analyses were also conducted, entering NT as a covariate of interest. Significance was assessed using a combination of cluster-forming p < 0.001 voxel-level threshold and p-FDR < 0.05 cluster-size threshold64.

Brain-behavior correlation analysis

Correlations were tested between behavioral interference (RT and error rates) and brain metrics (activation and FC). Moderation analyses were conducted to assess whether NT influenced the relationship between brain metrics and behavioral interference, using the PROCESS macro for SPSS65.

Results

Behavioral results

As expected, EI trials elicited longer RTs (t(64) = 8.87, p < 0.001) and higher error rates (t(64) = 4.26, p < 0.001) than EC trials, confirming the emotional Stroop interference effect (Supplementary Table 2). Interference scores (EI minus EC) for RTs and error rates were calculated. NT scores were not significantly correlated with interference scores for RTs (r = 0.16, p = 0.19) or error rates (r = 0.16, p = 0.21).

fMRI results

Association between NT and brain activation

Consistent with prior studies using emotional conflict tasks33,35,36,37, significant activation was observed in the lateral prefrontal cortex and medial frontal cortex (EI vs. EC contrast; FDR q < 0.05, whole-brain corrected). Specifically, the cluster for the lateral prefrontal cortex encompassed the dlPFC, extending into the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC). The medial frontal cortex cluster included the aMCC, extending into the pre-SMA and the dmPFC. Additionally, consistent with findings from meta-analyses of emotional inference tasks, including emotional conflict tasks66,67, activation was also observed in the bilateral anterior insula (aI) and the inferior parietal lobule (IPL) regions in the EI vs. EC contrast (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Brain regions showing significant activation in the EI vs. EC contrast. aMCC anterior midcingulate cortex, pre-SMA pre-supplementary motor area, aI anterior insula, vlPFC ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, IPL inferior parietal lobule, dlPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, WB.FDR whole brain FDR corrected. Brain images were generated using MRIcroGL software (version 1.2.20220720), available at https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mricrogl.

First, ROI analyses revealed no significant NT-related differences in activation within the aMCC, the bilateral dlPFC, or the bilateral amygdala (ps > 0.23). Similarly, when NT scores were included as a covariate of interest into the regression model, whole-brain analysis showed no significant NT-related differences in brain activation patterns (EI vs. EC contrast; FDR q < 0.05, whole-brain corrected). Under a less stringent threshold (p < 0.001, uncorrected), however, NT scores were positively correlated with activation in the left inferior frontal gyrus and negatively correlated with activation in the posterior cingulate cortex, extending to the precuneus.

Association between NT and functional connectivity

The association between NT and FC was examined using the aMCC as the seed region in the gPPI analysis. The results indicated that NT was associated with decreased FC between the aMCC and the left dlPFC (r = − 0.32, p = 0.010) as well as the left amygdala (r = − 0.25, p = 0.042) in the EI vs. EC contrast (Fig. 3). These associations remained significant even after controlling for age and gender (see Supplementary Materials for details). Furthermore, whole-brain gPPI analysis showed that NT was associated with reduced FC between the aMCC and both the left frontal pole and the bilateral occipital pole regions (EI vs. EC contrast; uncorrected voxel-wise cluster-forming threshold p < 0.001 and FDR-corrected cluster-level q < 0.05; Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Functional connectivity modulated by NT. NT was associated with reduced FC between the aMCC and the left dlPFC as well as the left amygdala in EI vs. EC contrast. The green circle indicates the aMCC seed region used in the gPPI analysis; aMCC anterior midcingulate cortex, dlPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, FC functional connectivity; aMCC peak MNI coordinate (x = − 6, y = 18, z = 46); left dlPFC peak MNI coordinate (x = − 52, y = 18, z = 32). Brain images were generated using MRIcroGL software (version 1.2.20220720), available at https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mricrogl.

Brain-behavior correlations

Decreased FC between the aMCC and the left dlPFC was associated with higher interference in RT on a trend-level (r = − 0.23, p = 0.062). No other significant brain-behavior correlations or NT moderation effects emerged (see Supplementary Results for details).

Discussion

The present study investigated the neural mechanisms underlying alterations in cognition-emotion interactions in NT, specifically during emotional conflict. As expected, the task robustly activated the frontal-parietal (dlPFC, IPL) and cingulo-opercular (aMCC, aI) network regions66,67. gPPI analyses further revealed that higher NT was associated with weaker FC between the aMCC and both the amygdala and the dlPFC. However, none of the a priori ROIs (i.e., aMCC, dlPFC, and amygdala) exhibited modulated activation by NT. Implications of the present findings are discussed below.

First, we found that as NT increased, the FC between the aMCC and the left amygdala decreased during emotional conflict. The functional interaction between the aMCC and the amygdala is known to be critical for the processing and regulating emotional information22,31. In contexts where emotional stimuli are task-irrelevant or in conflict with task demands, the close coupling of these two regions is especially important. The aMCC mediates emotional signals from the amygdala triggered by emotional distracters, thereby facilitating goal-directed responses68,69. The current findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of NT show weakened coupling within the aMCC-amygdala circuitry. This diminished connectivity may reflect impaired regulatory control over emotional distractors, increased vigilance toward emotional distractors, or both. Notably, inefficient cortical inhibition of amygdala activity has been consistently reported in patients with emotional disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and depression3,70,71,72. However, relatively few studies have examined whether heightened levels of NT exhibit a similar pattern. The findings from this study suggest that aberrant neural coupling in the aMCC-amygdala circuitry may serve not only as an outcome of clinical symptoms but also as a potential risk factor. This dysregulation could contribute to difficulties in coping with stress and regulating emotions in daily life among individuals with high NT.

In addition to weakened aMCC-amygdala connectivity, we observed NT was associated with decreased FC between the aMCC and the left dlPFC. The aMCC serves as a key hub in the brain, supporting functions related to both emotional processing but also higher-order cognitive control23,24,25. As part of the dorsal cognitive control system, the aMCC plays a critical role in conflict monitoring and detection, and its efficient communication with the dlPFC is essential for executing goal-directed responses26,27,28. Supporting this notion, we found a trend indicating that decreased FC between the aMCC and the left dlPFC was associated with higher RT interference. Furthermore, the present findings suggest that individuals with high levels of NT tend to exhibit inefficient communication within the aMCC-dlPFC circuitry during emotional conflict.

These results align with prior studies suggesting that emotional distractors or conflicts introduce a competition between top-down cognitive control and bottom-up emotion processing brain regions73,74. NT may exacerbate this competition, reducing the resources available for ongoing cognitive control73,7579. In fact, Hur et al.76 found that in individuals with high NT, reduced activity in top-down control regions (e.g., IFG, aMCC) during the color-word Stroop task was further intensified under negative emotional states. Together, these findings suggest that inefficiencies in higher-order cognitive control functions may become particularly pronounced among individuals with high NT during emotionally conflicting or distracting situations. Alterations in neural coupling within the aMCC-dlPFC circuitry may underlie attentional difficulties and executive function deficits in emotionally challenging contexts for these individuals.

It is noteworthy that our study did not find modulated brain activation in any of the a priori regions (i.e., amygdala, aMCC, and dlPFC) during emotional conflict. Although only a few studies have investigated this, the findings have been mixed regarding whether NT modulates brain activation during emotional conflicts. For example, although Haas et al.38 reported heightened amygdala activation in high-NT individuals, this finding was limited by a relatively small sample size, increasing the risk of Type I error. A meta-analysis with a large sample size did not find significant associations between NT and amygdala reactivity to negative stimuli14. Similarly, while some studies have reported positive associations between NT and aMCC activation during emotional interference or conflict tasks37,68,77, others failed to replicate these findings78. The results of the current study suggest that changes in brain activation within isolated regions may not reliably explain the neural mechanisms underlying NT. Instead, the neurobiological substrates of NT may be better characterized by examining alterations in the efficiency of communication between key brain regions involved in integrating bottom-up emotion and top-down cognitive control processes, particularly during emotional conflict.

Despite its novel insights, this study is not without limitations. First, the sample exclusively included non-clinical participants to explore the neural substrates of NT as a risk factor for anxiety and depression. To clarify whether the observed neural patterns contribute to the onset and maintenance of emotional disorders, longitudinal studies are needed to establish causal relationships between NT, observed neural patterns, and clinical symptoms. Second, although control analyses with age and gender revealed consistent results, the predominance of female participants and the final sample size not meeting recent recommendations44 remain potential limitations. Replication studies with a larger, more gender-balanced sample are needed, while also controlling for other potential confounding factors (e.g., education level, emotional states during the experiment). Third, we observed that NT modulated the neural coupling amongst key brain regions rather than their activities per se. To better understand the neural mechanisms associated with NT, future research should incorporate advanced analytic techniques, such as multivariate pattern analysis and whole-brain connectome-based FC analysis. Finally, although our study identified altered FC between the aMCC and both the amygdala and dlPFC, gPPI analyses do not provide information about the directionality of influences. Future research could employ methods like effective connectivity analysis to infer causal relationships between these regions.

In summary, the present findings suggest that the neural mechanisms underlying NT during emotional conflict are best characterized by weakened coupling between regions responsible for emotion processing and cognitive control, as well as within the cognitive control network. These observations provide valuable insights into neurobiological vulnerability markers that may predispose individuals to the development of anxiety and depression.

Data availability

Processed data are publicly available at Open Science Framework website: https://osf.io/mzyr4/.

References

Eysenck, H. J. Biological dimensions of personality. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (ed. Pervin, L. A.) 244–276 (The Guilford Press, 1990).

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO personality inventory. Psychol. Assess. 4, 5 (1992).

Barlow, D. H., Sauer-Zavala, S., Carl, J. R., Bullis, J. R. & Ellard, K. K. The nature, diagnosis, and treatment of neuroticism: Back to the future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2, 344–365 (2014).

Kotov, R., Gamez, W., Schmidt, F. & Watson, D. Linking big personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 136, 768 (2010).

Lahey, B. B. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am. Psychol. 64, 241 (2009).

Jeronimus, B., Kotov, R., Riese, H. & Ormel, J. Neuroticism’s prospective association with mental disorders halves after adjustment for baseline symptoms and psychiatric history, but the adjusted association hardly decays with time: A meta-analysis on 59 longitudinal/prospective studies with 443 313 participants. Psychol. Med. 46, 2883–2906 (2016).

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R. & Calvo, M. G. Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion 7, 336 (2007).

Davis, M. & Whalen, P. J. The amygdala: Vigilance and emotion. Mol. Psychiatry 6, 13–34 (2001).

Chan, S. W., Norbury, R., Goodwin, G. M. & Harmer, C. J. Risk for depression and neural responses to fearful facial expressions of emotion. Br. J. Psychiatry 194, 139–145 (2009).

Stein, M. B., Simmons, A. N., Feinstein, J. S. & Paulus, M. P. Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety-prone subjects. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 318–327 (2007).

Hooker, C. I., Verosky, S. C., Miyakawa, A., Knight, R. T. & D’Esposito, M. The influence of personality on neural mechanisms of observational fear and reward learning. Neuropsychologia 46, 2709–2724 (2008).

Grogans, S. E. et al. Neuroticism/negative emotionality is associated with increased reactivity to uncertain threat in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, not the amygdala. J. Neurosci. 44 (2024).

Ormel, J. et al. The biological and psychological basis of neuroticism: Current status and future directions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 59–72 (2013).

Servaas, M. N. et al. Neuroticism and the brain: A quantitative meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies investigating emotion processing. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 1518–1529 (2013).

Basten, U., Stelzel, C. & Fiebach, C. J. Trait anxiety modulates the neural efficiency of inhibitory control. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23, 3132–3145 (2011).

Bishop, S. J. Trait anxiety and impoverished prefrontal control of attention. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 92–98 (2009).

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D. & Satpute, A. B. Personality from a controlled processing perspective: An fMRI study of neuroticism, extraversion, and self-consciousness. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 5, 169–181 (2005).

Szameitat, A. J., Saylik, R. & Parton, A. Neuroticism related differences in the functional neuroanatomical correlates of multitasking. An fMRI study. Neurosci. Lett. 635, 51–55 (2016).

Dolcos, F., Iordan, A. D. & Dolcos, S. Neural correlates of emotion–cognition interactions: A review of evidence from brain imaging investigations. J. Cogn. Psychol. 23, 669–694 (2011).

Kim, M. J. et al. The structural and functional connectivity of the amygdala: From normal emotion to pathological anxiety. Behav. Brain Res. 223, 403–410 (2011).

Pessoa, L. On the relationship between emotion and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 148–158 (2008).

Ray, R. D. & Zald, D. H. Anatomical insights into the interaction of emotion and cognition in the prefrontal cortex. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 479–501 (2012).

Heilbronner, S. R. & Hayden, B. Y. Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: A bottom-up view. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 39, 149–170 (2016).

Shackman, A. J. et al. The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 154–167 (2011).

Vogt, B. A. Midcingulate cortex: Structure, connections, homologies, functions and diseases. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 74, 28–46 (2016).

Botvinick, M. M., Cohen, J. D. & Carter, C. S. Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: An update. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8, 539–546 (2004).

Kerns, J. G. et al. Anterior cingulate conflict monitoring and adjustments in control. Science 303, 1023–1026 (2004).

Smith, E. H. et al. Widespread Temporal coding of cognitive control in the human prefrontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1883–1891 (2019).

Etkin, A., Egner, T. & Kalisch, R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 85–93 (2011).

Wager, T. D. et al. Pain in the ACC? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, E2474–E2475 (2016).

Etkin, A., Büchel, C. & Gross, J. J. The neural bases of emotion regulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 693–700 (2015).

Pezawas, L. et al. 5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: A genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 828–834 (2005).

Comte, M. et al. Dissociating bottom-up and top-down mechanisms in the cortico-limbic system during emotion processing. Cereb. Cortex. 26, 144–155 (2016).

Quaedflieg, C. et al. Temporal dynamics of stress-induced alternations of intrinsic amygdala connectivity and neuroendocrine levels. PLoS One 10, e0124141 (2015).

Haas, B. W., Omura, K., Constable, R. T. & Canli, T. Interference produced by emotional conflict associated with anterior cingulate activation. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 6, 152–156 (2006).

Egner, T., Etkin, A., Gale, S. & Hirsch, J. Dissociable neural systems resolve conflict from emotional versus nonemotional distracters. Cereb. Cortex 18, 1475–1484 (2008).

Krug, M. K. & Carter, C. S. Adding fear to conflict: A general purpose cognitive control network is modulated by trait anxiety. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 10, 357–371 (2010).

Haas, B. W., Omura, K., Constable, R. T. & Canli, T. Emotional conflict and neuroticism: Personality-dependent activation in the amygdala and subgenual anterior cingulate. Behav. Neurosci. 121, 249 (2007).

Salinas, E. & Sejnowski, T. J. Correlated neuronal activity and the flow of neural information. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 539–550 (2001).

Stevens, M. C. The developmental cognitive neuroscience of functional connectivity. Brain Cogn. 70, 1–12 (2009).

Shackman, A. J. et al. Dispositional negativity in the wild: Social environment governs momentary emotional experience. Emotion 18, 707–724 (2018).

Hur, J. et al. Anxiety-related frontocortical activity is associated with dampened stressor reactivity in the real world. Psychol. Sci. 33, 906–924 (2022).

Griffith, J. W. et al. Neuroticism as a common dimension in the internalizing disorders. Psychol. Med. 40, 1125–1136 (2010).

Grady, C. L., Rieck, J. R., Nichol, D., Rodrigue, K. M. & Kennedy, K. M. Influence of sample size and analytic approach on stability and interpretation of brain-behavior correlations in task-related fMRI data. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42, 204–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25217 (2021).

Yarkoni, T. Big correlations in little studies: Inflated fMRI correlations reflect low statistical power—Commentary on Vul et al. (2009). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 4, 294–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01127.x (2009).

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. The revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R). In The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment 2, 179–198 (2008).

Soto, C. J. & John, O. P. The next big five inventory (BFI-2): Developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 113, 117 (2017).

Gray, J. A. A critique of Eysenck’s theory of personality. In A Model for Personality (ed. Eysenck, H. J.) 246–276 (Springer, 1981).

Hong, Y., Nam, Y. & Lee, Y. Developing Korean affect word list and it’s application. Korean J. Cogn. Sci. 27, 377–406 (2016).

Conley, M. I. et al. The Racially diverse affective expression (RADIATE) face stimulus set. Psychiatry Res. 270, 1059–1067 (2018).

Esteban, O. et al. fMRIPrep: A robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods 16, 111–116 (2019).

Gorgolewski, K. et al. Nipype: A flexible, lightweight and extensible neuroimaging data processing framework in python. Front. Neuroinformatics. 5, 12318 (2011).

Jenkinson, M., Bannister, P., Brady, M. & Smith, S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 17, 825–841 (2002).

Cox, R. W. & Hyde, J. S. Software tools for analysis and visualization of fMRI data. NMR Biomed. 10, 171–178 (1997).

Greve, D. N. & Fischl, B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. Neuroimage 48, 63–72 (2009).

Pruim, R. H. et al. ICA-AROMA: A robust ICA-based strategy for removing motion artifacts from fMRI data. Neuroimage 112, 267–277 (2015).

Yarkoni, T., Poldrack, R. A., Nichols, T. E., Van Essen, D. C. & Wager, T. D. Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data. Nat. Methods 8, 665–670 (2011).

Rolls, E. T., Huang, C. C., Lin, C. P., Feng, J. & Joliot, M. Automated anatomical labelling atlas 3. Neuroimage 206, 116189 (2020).

Van Snellenberg, J. X. & Wager, T. D. Cognitive and motivational functions of the human prefrontal cortex. In Luria’s Legacy in the 21st Century (eds. Christiansen, A.-L., Goldberg, E. & Bougakov, D.) 30–61 (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Kragel, P. A. et al. Generalizable representations of pain, cognitive control, and negative emotion in medial frontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 283–289 (2018).

Vermeylen, L. et al. Shared neural representations of cognitive conflict and negative affect in the medial frontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 40, 8715–8725 (2020).

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Nieto-Castanon, A. Conn: A functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2, 125–141 (2012).

McLaren, D. G., Ries, M. L., Xu, G. & Johnson, S. C. A generalized form of context-dependent psychophysiological interactions (gPPI): A comparison to standard approaches. Neuroimage 61, 1277–1286 (2012).

Chumbley, J., Worsley, K., Flandin, G. & Friston, K. Topological FDR for neuroimaging. Neuroimage 49, 3057–3064 (2010).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction To Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-based Approach (Guilford Publications, 2017).

Song, S. et al. The influence of emotional interference on cognitive control: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies using the emotional Stroop task. Sci. Rep. 7, 2088 (2017).

Xu, M., Xu, G. & Yang, Y. Neural systems underlying emotional and non-emotional interference processing: An ALE meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10, 220 (2016).

Han, H. J., Lee, K., Kim, H. T. & Kim, H. Distinctive amygdala subregions involved in emotion-modulated Stroop interference. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9, 689–698 (2014).

Kanske, P. On the influence of emotion on conflict processing. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 6, 42 (2012).

Etkin, A., Prater, K. E., Hoeft, F., Menon, V. & Schatzberg, A. F. Failure of anterior cingulate activation and connectivity with the amygdala during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 167, 545–554 (2010).

Fales, C. L. et al. Altered emotional interference processing in affective and cognitive-control brain circuitry in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry. 63, 377–384 (2008).

Lorberbaum, J. P. et al. Neural correlates of speech anticipatory anxiety in generalized social phobia. Neuroreport 15, 2701–2705 (2004).

Iordan, A. D., Dolcos, S. & Dolcos, F. Neural signatures of the response to emotional distraction: A review of evidence from brain imaging investigations. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 200 (2013).

Mitchell, D. G. et al. The interference of operant task performance by emotional distracters: An antagonistic relationship between the amygdala and frontoparietal cortices. Neuroimage 40, 859–868 (2008).

Kalanthroff, E., Henik, A., Derakshan, N. & Usher, M. Anxiety, emotional distraction, and attentional control in the Stroop task. Emotion 16, 293 (2016).

Hur, J. et al. Interactive effects of trait and state affect on top-down control of attention. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 10, 1128–1136 (2015).

Comte, M. et al. Effect of trait anxiety on prefrontal control mechanisms during emotional conflict. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 2207–2214 (2015).

Barker, H. et al. Worry is associated with inefficient functional activity and connectivity in prefrontal and cingulate cortices during emotional interference. Brain Behav. 8, e01137 (2018).

Hur, J., Stockbridge, M. D., Fox, A. S. & Shackman, A. J. Dispositional negativity, cognition, and anxiety disorders: An integrative translational neuroscience framework. Progress in brain research 247, 375–436 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (Grant Nos. 2021S1A5A2A03070229 and RS-2024-00342770) and the International Joint Research Grant from Yonsei Graduate School.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K. served as the lead for conceptualization, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, and writing the original draft. J.P. contributed toward conceptualization, data curation, and investigation. M.K. contributed toward data processing and analysis. M.J.K. contributed toward funding acquisition and project administration. J.H. funded and supervised all aspects of the study. All authors contributed to reviewing and revising the paper and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Park, J., Kuhn, M. et al. Neuroticism modulates functional connectivity of the midcingulate cortex during emotional conflict. Sci Rep 15, 13095 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97529-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97529-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The role of amygdala reactivity in affective fluctuations across social contexts

Scientific Reports (2025)