Abstract

In low- and middle-income countries, undernutrition often coexists with rising obesity, creating a double burden of malnutrition (DBM). Our study employs a mathematical approach to examine how maternal socioeconomic status (SES) impacts child growth in Iranian children from infancy to age two, offering new insights into strategies for tackling both undernutrition and obesity. We used data from the PERSIAN Birth Cohort. SES was divided into quintiles using multiple correspondence analysis (MCA), and child growth was assessed with eight indicators. Missing data were handled via multiple imputation (MI). SES impacts on growth were analyzed using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE), and BMI-Z was predicted from WAZ and HAZ through linear regression by SES and age. We explored obesity risk by comparing HAZ-to-WAZ ratios from GEE models with WAZ-to-HAZ beta ratios from regressions. Sensitivity analyses compared MI with complete-case analyses (CCA). 7169 neonates were assessed at 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 months. SES increasingly improved WAZ with age, preventing underweight in higher SES groups. SES consistently improved HAZ, significantly enhancing stunting prevention in higher SES groups. The impact on BMI-Z increased with age, peaking in Very High SES, which shows a significant rise in obesity risk by 24 months. Comparing ratios from GEE and regression models, we found that GEE ratios were lower where BMI-Z increased. Sensitivity analysis confirmed MI and CCA consistency. Addressing DBM requires understanding how imbalanced increases in HAZ and WAZ heighten obesity risk. Future research should focus on targeted interventions to manage DBM effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The developmental origins of health and disease concept links early-life factors, particularly in the first 1000 days, to long-term health1,2,3. Growth impairment, often from undernutrition, contributes to childhood morbidity, mortality, and long-term health issues, highlighting the importance of early intervention4,5.

Our previous study6 examined obesity as a complication of undernutrition6,7, emphasizing the need to assess multiple nutritional indicators in children together6,8. Cole’s BMI-Z formula9, 1.434 × WAZ − 0.794 × HAZ, shows that maintaining BMI-Z requires HAZ to change twice as much as WAZ in the same direction. This offers a mathematical basis for the double burden of malnutrition (DBM), seen at individual, household, and population levels10. Population-level DBM involves high rates of undernutrition and obesity7,8,11,12,13. Despite WHO strategies, interventions remain limited with uncertain outcomes8. The WHO emphasizes addressing DBM to meet Sustainable Development Goal 2 and Target 3.414.

Understanding preventable causes of undernutrition is key for effective interventions. The UNICEF framework identifies socioeconomic status (SES) as a basic factor4.

Previous studies3,15,16 primarily examined low SES and undernutrition indicators separately, overlooking their interplay. Most relied on cross-sectional designs, missing the temporal relationship between SES and children’s growth at key stages (6, 12, and 24 months). Birth cohort studies, with their longitudinal approach, offer a clearer perspective on child growth dynamics6.

In the PERSIAN Birth Cohort, we explore the link between maternal SES and eight growth and nutritional indicators in Iranian children from infancy to two years, offering insights into the DBM.

Methods

Study design and sample

Details of the PERSIAN Birth Cohort17, a prospective population-based study, were reported previously. Enrollment began in 2016–2017 in five Iranian cities (Isfahan, Yazd, Semnan, Rafsanjan, and Sari), with Sari data excluded due to technical issues. Pregnant women were enrolled regardless of prior pregnancies or fertility treatments, if residing in the area for at least one year. Only the first pregnancy they were enrolled in during the study and live births were included, with growth assessments at 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 months.

Variables and measurements

Maternal SES, the exposure variable, was assessed through a baseline questionnaire covering education, housing, assets, income, car price, food purchasing ease, bill payment, and insurance status via face-to-face interviews18.

Child growth, the study outcome, was assessed using eight nutritional indicators: Height-for-age (HAZ), Weight-for-age (WAZ), Weight-for-height (WHZ), and body mass index-for-age (BMI-Z), following WHO Child Growth Standards. Malnutrition was classified with z-scores below -2 for low HAZ (stunting), low WHZ (wasting), and low WAZ (underweight)19. Obesity, including overweight, was defined by a BMI-Z score above 220.

Health professionals conducted anthropometric measurements using standardized equipment per Iranian Directorate of Health guidelines. The measurements were entered into the WHO Anthro Survey Analyzer to obtain z-scores. Implausible values were excluded (WAZ: < − 6 or > + 5; HAZ: < − 6 or > + 6; WHZ/BMI-Z: < − 5 or > + 5)19.

Mothers were asked to refer to their children’s birth cards for birth weight and length.

A Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) was used to identify potential confounders and determine the minimum variable set needed for unbiased results21: maternal age, gravidity, study center, maternal chronic diseases, mental health, and prepregnancy smoking. The DAG was created with http://www.dagitty.net (Supplemental Fig. 1). Marital status was excluded due to limited variation. Maternal chronic diseases included cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, asthma, thyroid disease, autoimmune conditions, epilepsy, and cancer. Mental health factors included anxiety and depression. Prepregnancy smokers were women who smoked regularly before pregnancy.

Statistical analysis

A multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was used to construct an SES index, categorizing participants into five SES quintiles, from lowest (1st) to highest (5th).

We assessed missing data by calculating proportions, ranging from 27.91 to 33.17% across all time points. Missing data increased with child age, as detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

We used Little’s MCAR test to assess missing data mechanisms and analyzed patterns with t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical ones. Since missingness in our outcomes was unrelated to strongly correlated variables (birthweight z-score and gestational age), we assumed a Missing at Random (MAR) pattern. We then employed multiple imputation under the MAR assumption using Chained Equations with Predictive Mean Matching (PMM) to estimate the missing values for WAZ, HAZ, WHZ, and BMI-Z. We selected auxiliary variables with minimal missing data related to the missingness mechanism (Little’s MCAR test), including SES and cohort center. Additional variables, such as gender, birth weight z-score, and gestational age, were included based on their correlation with the outcome or predictive strength. Pearson correlations and regression analyses identified these relationships.

Stunting, wasting, underweight, and obesity were categorized as passive variables, derived from imputed data, while maternal age, gravidity, smoking, chronic diseases, and mental health were considered regular variables. We generated 20 imputed datasets to ensure robustness.

We applied generalized estimating equations (GEE)22 to investigate the association between maternal SES and child growth and nutritional indicators, using a Gaussian family with an identity link for continuous outcomes and a binomial family with a logit link for binary outcomes. Both models assumed exchangeable correlation. Interaction terms with p-values < 0.1 were considered significant. If significant, all potential confounders were included for validity23; otherwise, we applied the change-in-estimate (CIE) criterion with backward deletion to identify confounders modifying the SES-beta coefficient by > 10%.24. We calculated the ratios of predicted contrasts between HAZ and WAZ to determine SES’s influence on changes in HAZ relative to WAZ. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for these ratios were estimated using the bootstrap method. We then predicted individual outcome values and conducted linear regression models for BMI-Z as a function of WAZ and HAZ, separately by maternal SES level and child age, following Cole et al.'s approach9, to account for age-dependent relationships and improve model fit. We subsequently calculated the ratio of the HAZ to WAZ beta coefficients. The 95% CIs for these ratios were estimated using the bootstrap method.

According to Cole’s formula, BMI-Z increases if HAZ changes less than β WAZ/β HAZ times as much as WAZ in the same direction. We used Wald’s test to compare HAZ contrast/WAZ contrast with β WAZ/β HAZ.

To assess robustness, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by comparing results from the Multiple Imputation (MI) with those from a Complete-Case Analysis (CCA).

Statistical analyses were performed in Stata 17, with 80% power and a 0.05 significance level.

In this manuscript, we refer to "effect/impact"; however, it is important to recognize that, in observational research such as cohort studies, these metrics more accurately represent "association," as they focus on observed relationships rather than causal effects.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to all relevant institutional and national guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. Ethical approval for this research was granted by the Research and Medical Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR.TUMS.DDRI.REC.1399.026). Additionally, the PERSIAN Birth Cohort received ethical approval from the same committee (Approval ID: IR.TUMS.DDRI.REC.1396.1).

Results

Participants

The study initially enrolled 9,015 pregnant Iranian women. After excluding 472 abortions, 70 intrauterine fetal deaths, 46 neonatal deaths, and 1,379 with missing birth data, 7,169 neonates were included and assessed at 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 months (Fig. 1). Maternal and neonatal characteristics, including missing data, are detailed in Table 1. Maternal SES distribution across PERSIAN Birth Cohort centers is shown in Supplemental Fig. 2. SES indices for each quintile are in Supplemental Table 1, and summary measures of children’s nutritional and growth indicators by SES and age are in Table 2.

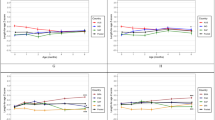

WAZ and underweight

The association between maternal SES and WAZ strengthens with age, as indicated by increasing β-values for the interaction between SES and child’s age (Table 3, Supplemental Fig. 3). Higher SES groups show more pronounced effects over time.

Consistent with these findings, children in High SES (OR = 0.751, p = 0.020) and Very High SES (OR = 0.709, p = 0.010) are significantly less likely to be underweight (WAZ < − 2) compared to those in Very Low SES. However, unlike WAZ, maternal SES does not affect underweight status differently with age (Table 4).

Table 5 shows that while contrasts for lower SES are positive, they lack the early and consistent significance seen in Very High SES, which shows a stronger, cumulative impact on WAZ as children age.

Children in Yazd have lower WAZ (β = − 0.163, p < 0.001) compared to Isfahan, but no significant differences in underweight odds across centers.

Maternal age slightly reduces WAZ (β = − 0.008, p = 0.001), while higher gravidity increases WAZ (β = 0.029, p = 0.015) and lowers underweight odds (OR = 0.917, p < 0.05). Each additional month of age slightly decreases underweight odds (OR = 0.974, p < 0.001).

No significant associations were found between WAZ or underweight and maternal anxiety and depression, chronic disease, or smoking (Tables 3 and 4).

HAZ and stunting

Maternal SES shows a gradient relationship with HAZ, with Very High SES children showing the greatest improvement (β = 0.169, p < 0.001), followed by High SES (β = 0.088, p = 0.023). Intermediate (β = 0.051, p = 0.187) and Low SES (β = 0.039, p = 0.313) show weaker, non-significant effects (Table 3).

High SES children have significantly lower odds of stunting (OR = 0.616, p < 0.001), reflecting a 38.4% reduction compared to Very Low SES. Very High SES also shows reduced odds, though marginally significant (OR = 0.767, p = 0.054). Maternal SES associations with HAZ and stunting do not change with age.

Children from Yazd (β = 0.290, p < 0.001) and Semnan (β = 0.118, p = 0.002) have higher HAZ than those from Isfahan. Yazd children are less likely to be stunted (OR = 0.649, p < 0.001). Each additional month of child age reduces stunting odds by 4.4% (OR = 0.956, p < 0.001), while each year of maternal age increases the odds by 2.4% (OR = 1.024, p = 0.009). Anxiety and depression, and smoking show no significant associations with HAZ or stunting.

WHZ and wasting

The relationship between maternal SES and child WHZ changes with age. WHZ decreases by 0.015 units per month (p < 0.001), but this decline is smaller in higher SES groups. Positive interaction terms for Middle SES × Age (β = 0.005, p = 0.065), High SES × Age (β = 0.012, p < 0.001), and Very High SES × Age (β = 0.016, p < 0.001) show that higher SES lessens the age-related decline in WHZ.

Predicted contrasts show that higher SES impacts WHZ more strongly as age increases, especially after the first year. Middle SES has significant WHZ gains at 12 months (MD = 0.092, 95% CI 0.019, 0.166) and larger gains at 24 months (MD = 0.149, 95% CI 0.044, 0.254). High SES shows significant gains only at 24 months (MD = 0.218, 95% CI 0.096, 0.340). Very High SES has the largest gains, significant from 6 months (MD = 0.095, 95% CI 0.016, 0.175), continuing through 12 months (MD = 0.194, 95% CI 0.108, 0.279) and 24 months (MD = 0.391, 95% CI 0.245, 0.536).

The odds of wasting (WHZ < -2) are significantly lower in Middle SES (OR = 0.814, p = 0.013), High SES (OR = 0.839, p = 0.045), and Very High SES (OR = 0.781, p = 0.006) compared to Very Low SES. Unlike WHZ, SES’s association with wasting does not change with age.

Children from Yazd have lower WHZ (β = − 0.476, p < 0.001) and over twice the odds of wasting (OR = 2.236, p < 0.001) compared to Isfahan. No significant differences are observed for Rafsanjan and Semnan. Older maternal age slightly reduces WHZ (β = − 0.005, p = 0.031), while higher gravidity increases it (β = 0.037, p = 0.003). Anxiety and depression, chronic diseases, and smoking show no significant links to WHZ or wasting.

BMI-Z and obesity

BMI-Z shows a small but significant monthly decrease of 0.010 units (p < 0.001). The association between of SES and BMI-Z changes with age. Table 3 and Supplemental Fig. 3 highlight significant positive interactions for High SES × Age (β = 0.010, p = 0.004) and Very High SES × Age (β = 0.013, p = 0.001), suggesting a smaller decline in BMI-Z with age for these groups.

Predicted contrasts in Table 5 and Supplemental Fig. 3 show that higher SES improves BMI-Z, with the most significant effects at older ages. Children from Very High SES exhibit the largest improvements at 6, 12, and 24 months, while Middle and High SES children show notable gains from 12 months onward.

Table 4 shows that the odds of obesity increase with age (OR = 1.021, p = 0.030). The association of maternal SES with obesity varies with age, with only the Very High SES × Child’s Age interaction being significant (OR = 1.028, p = 0.045).

Predicted contrasts show that at 12 months, Very High SES is linked to a non-significant increase in obesity (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 0.867 to 1.59). By 24 months, the effect becomes significant (OR = 1.636, 95% CI 1.043 to 2.566).

Children from Yazd had lower BMI-Z scores (β = − 0.445, p < 0.001) and reduced odds of obesity (OR = 0.585, p < 0.001) compared to those from Isfahan. Maternal age slightly decreased BMI-Z (β = − 0.006, p = 0.011), while higher gravidity increased it (β = 0.039, p = 0.002). Anxiety and depression, chronic diseases, and smoking had no significant effects.

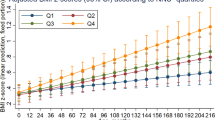

Comparing ratio estimates: (HAZ contrast/WAZ contrast) vs. (β WAZ/β HAZ)

Significant associations between maternal SES and child HAZ and BMI-Z were found only in High and Very High SES groups, which this manuscript focuses on.

Table 5 presents p-values comparing two estimates: the ratio of predicted contrasts from GEE models and the ratio of beta coefficients from regression models predicting BMI-Z. Our BMI-Z formula (1.394 × WAZ − 0.795 × HAZ) is similar to Cole’s (1.434 × WAZ − 0.794 × HAZ). After adjusting for confounders with GEE models, we predicted BMI-Z and performed linear regression to estimate it as a function of WAZ and HAZ across maternal SES levels and child ages. Beta coefficients for WAZ ranged from 1.046 to 1.246, and for HAZ from − 0.914 to − 0.814, varying by age and SES (Supplemental Table 2). We then compared the ratio of beta coefficients with the ratio of predicted contrasts from GEE models using Wald’s test. As shown in Table 5, where BMI-Z increased, the HAZ/WAZ contrast ratio was significantly lower than β WAZ/β HAZ. In the High SES group at 4 and 6 months, where BMI-Z remained constant, the ratios were not significantly different. At 2 months, where BMI-Z decreased in High SES, the HAZ/WAZ contrast ratio was higher than β WAZ/β HAZ (2.434, p = 0.087, marginally significant).

Sensitivity analysis

We assessed robustness by comparing results from MI and CCA, focusing on missing data impacts on SES and child age interactions (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Both methods yielded consistent estimates, confirming the stability of SES associations with growth indicators. CCA had wider confidence intervals due to a smaller sample, but SES-related findings remained significant, ensuring reliable conclusions.

Discussion

This study examines maternal SES’s impact on eight key growth and nutritional indicators in children up to age two, using Cole’s BMI-Z formula (1.434 × WAZ − 0.794 × HAZ)9. By analyzing SES’s influence on these indicators together, we highlight the complex dynamics of the DBM.

Maternal SES shows an increasing association with child WAZ as age progresses, demonstrating positive relationships even in lower SES groups and stronger associations in higher SES groups, helping prevent underweight. SES consistently influenced HAZ, with significant associations observed only in higher SES groups, reducing stunting.

SES also affected WHZ, starting in Middle SES and strengthening in Very High SES, playing a key role in preventing wasting. Finally, maternal SES shows a growing association with BMI-Z, particularly in higher SES groups, with a notable increase in obesity risk by 24 months in the Very High SES group.

According to Cole’s formula, BMI-Z increases if HAZ changes less than β WAZ/β HAZ times as much as WAZ in the same direction. Table 5 shows that at most ages where SES increased BMI-Z, the HAZ contrast/WAZ contrast ratio was significantly lower than β WAZ/β HAZ, indicating a potential risk of obesity (BMI-Z > 2).

From a compatibility standpoint25,26,27, the confidence intervals for predicted contrasts of increased BMI-Z often included values near zero, indicating minimal SES-related impacts28. However, the effect became more pronounced at 24 months in the High SES group and at 12 and 24 months in the Very High SES group.

Consistent with these findings, the GEE model predicted a modest, non-significant increase in obesity risk at 24 months in the High SES group and at 12 months in the Very High SES group. By 24 months, the odds ratio for obesity in the Very High SES group significantly increased (OR = 1.636, 95% CI 1.043, 2.566), indicating a higher risk compared to Very Low SES. Notably, at 24 months, SES was linked to a BMI-Z increase of 0.357 (95% CI 0.223 to 0.492).

This finding aligns with the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation, which considers a BMI-Z reduction of more than 0.20–0.25 clinically significant29,30. Likewise, we define an increase beyond this threshold as clinically significant, with potential implications for obesity risk. An important consideration is whether this effect varies over time. The USPSTF’s threshold was based on long-term behavioral interventions lasting up to 12 months. Additionally, a study of 34,196 children found that those classified as overweight or obese maintained persistently higher BMI-Z scores from infancy, with a steady increase throughout childhood. Preschoolers experiencing a rapid annual BMI-Z change (0.2 to < 2.0) were more likely to develop overweight or obesity in adolescence31. In our study, SES influences BMI-Z cumulatively over time, as indicated by its significant interaction with the child’s age. The absence of an escalating effect limits this accumulation, reducing the likelihood of surpassing the obesity threshold.

Children in Yazd exhibit unique growth patterns, with higher odds of wasting, better height outcomes, lower stunting prevalence, and a lower likelihood of obesity. Odds of being underweight are similar, likely due to combined effects of wasting and stunting. Further research is needed to explore regional differences by employing the Social-Economic-Political-Emotional (SEPE) framework6,32 to examine the interactions between biological development and socioeconomic, cultural, political, and emotional factors.

A key limitation is the high rate of missing data at 24 months. We addressed this with MI and verified our findings by comparing MI with CCA, demonstrating the reliability of our results.

A key strength of our study is using Cole’s formula to assess the relationship between maternal SES, growth indicators, and DBM, highlighting how changes in WAZ and HAZ affect BMI-Z and offering insights for targeted DBM interventions.

Conclusion

This study employs a mathematical approach to examine the impact of maternal SES on child growth and nutritional status, utilizing Cole’s formula to explore the dynamics between growth indicators and the development of DBM. Our findings underscore the intricate nature of DBM and highlight the critical need for further research to identify its key determinants and develop targeted interventions for optimal child growth and nutrition. Future studies should refine the assessment of the effects of DBM determinants and interventions by exploring the relationships between the two ratios discussed and examining how their effects may change over time. Additionally, it is essential to evaluate these factors within specific populations to tailor more effective strategies for addressing DBM. This novel approach has the potential to significantly enhance efforts to manage DBM.

Data availability

All data relevant to this study are included in the article or provided as supplementary information. The analysis scripts and materials are available at https://github.com/GolnazRezaei80/Maternal-SES-Child-Growth. Access to the raw data is available on reasonable request, subject to approval by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. For data requests, please contact h.poustchi@gmail.com.

References

Juan, J. & Yang, H. Early life 1000 days: Opportunities for preventing adult diseases. Chin. Med. J. 135(5), 516–518 (2022).

Black, R. E. et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 382(9890), 427–451 (2013).

Akombi, B. J. et al. Stunting, wasting and underweight in sub-saharan Africa: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 14(8), 863 (2017).

Improving Child Nutrition: The achievable imperative for global progress - UNICEF DATA. https://data.unicef.org/resources/improving-child-nutrition-the-achievable-imperative-for-global-progress/.

Victora, C. G., De Onis, M., Hallal, P. C., Blössner, M. & Shrimpton, R. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: Revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics 125(3), e473–e480 (2010).

Rezaeizadeh, G. et al. Maternal education and its influence on child growth and nutritional status during the first two years of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 71, 102574 (2024).

Yajnik, C. S. Early life origins of the epidemic of the double burden of malnutrition: Life can only be understood backwards. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Southeast Asia. 28, 100453 (2024).

Sahiledengle, B. & Mwanri, L. Unveiling the crisis of the double burden of malnutrition. Lancet Glob. Heal. 12(3), e348–e349 (2024).

Cole, T. J. A chart to link child centiles of body mass index, weight and height. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 56(12), 1194–1199 (2002).

Double-duty actions for nutrition: policy brief. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-17.2.

Wells, J. C. et al. The double burden of malnutrition: aetiological pathways and consequences for health. Lancet 395(10217), 75–88 (2020).

Al-Awwad, N. J. et al. Review of the nutrition situation in Jordan: Trends and way forward. Nutrients 14(1), 135 (2022).

Popkin, B. M., Corvalan, C. & Grummer-Strawn, L. M. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet 395(10217), 65 (2020).

WHO EMRO | Double burden of nutrition | Nutrition site. https://www.emro.who.int/nutrition/double-burden-of-nutrition/index.html.

Ngandu, C. B. et al. The association between household socio-economic status, maternal socio-demographic characteristics and adverse birth and infant growth outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 11(4), 317–334 (2020).

Abate, K. H. & Belachew, T. Chronic malnutrition among under five children of ethiopia may not be economic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 29(2), 265 (2019).

Sakhvidi, M. J. Z. et al. The prospective epidemiological research studies in IrAN (PERSIAN) birth cohort protocol: Rationale, design and methodology. Longit. Life Course Stud. 12(2), 241–262 (2021).

Shafiei, S., Yazdani, S., Jadidfard, M. P. & Zafarmand, A. H. Measurement components of socioeconomic status in health-related studies in Iran. BMC Res. Notes. 12(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4101-y (2019).

Maharani Saraswati C. Quick guide WHO Anthro Survey Analyser. https://whonutrition.shinyapps.io/anthro.

Halilagic, A. & Moschonis, G. The effect of growth rate during infancy on the risk of developing obesity in childhood: A systematic literature review. Nutr 13(10), 3449 (2021).

Kyriacou, D. N., Greenland, P. & Mansournia, M. A. Using causal diagrams for biomedical research. Ann. Emerg. Med. 81(5), 606–613 (2023).

Hardin, J. W. & Hilbe, J. M. Generalized Estimating Equation, 1st ed. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420035285 (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2002).

Modeling Strategy for Assessing Interaction and Confounding. Logist Regres. 191–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-21647-2_7 (2002).

Hernán, M. A., Hernández-Diaz, S., Werler, M. M. & Mitchell, A. A. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: An application to birth defects epidemiology. Am. J. Epidemiol. 155(2), 176–184 (2002).

Mansournia, M. A., Nazemipour, M. & Etminan, M. P-value, compatibility, and S-value. Glob. Epidemiol. 4, 100085 (2022).

Greenland, S., Mansournia, M. A. & Joffe, M. To curb research misreporting, replace significance and confidence by compatibility: A Preventive Medicine Golden Jubilee article. Prev. Med. 164, 107127 (2022).

Mansournia, M. A. & Nazemipour, M. Recommendations for accurate reporting in medical research statistics. Lancet 403(10427), 611–612 (2024).

Mansournia, M. A. et al. A CHecklist for statistical Assessment of Medical Papers (the CHAMP statement): Explanation and elaboration. Br. J. Sports Med. 55(18), 1009–1017 (2021).

O’Connor, E. A. et al. Screening for obesity and intervention for weight management in children and adolescents: Evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA 317(23), 2427–2444 (2017).

Grossman, D. C. et al. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 317(23), 2417–2426 (2017).

Geserick, M. et al. Acceleration of BMI in early childhood and risk of sustained obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 379(14), 1303–1312 (2018).

Bogin, B. Social-Economic-Political-Emotional (SEPE) factors regulate human growth. https://doi.org/10.52905/hbph.v1.10 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt thanks to the authorities and staff at the participating medical universities for their crucial support and collaboration. We also appreciate the dedicated efforts of the entire project team. Most importantly, we are deeply grateful to the study participants and their families for their invaluable contributions to this research.

Funding

This research is part of a PhD thesis at Tehran University of Medical Sciences. While the PERSIAN Birth Cohort has received funding from the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education (grants 700/534, 700/110, 700/124, 700/121, and 700/1872), this specific study did not receive any direct financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.R. contributed to the study’s design and methodology, conducted the data analysis, interpreted the results, and authored the manuscript. M.A.M., as a supervisor, contributed to the study’s design and methodology, provided manuscript editing, verified data, and offered epidemiological consultation. M.Sh. accessed and verified the data and provided biostatistical consultation. S.Sh.D. served as the Isfahan local project manager. N.D. served as the Semnan local project manager. A.H.M. served as the Yazd local project manager. M.J.Z.Sh. acted as the overall coordinator. H.H. served as the Rafsanjan local project manager. Z.M. acted as the quality control manager. R.K. served as the supervisor, project administrator, and pediatric consultant. H.P., also a supervisor and project administrator, contributed to manuscript editing and provided epidemiological consultation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rezaeizadeh, G., Mansournia, M.A., Sharafkhah, M. et al. Maternal socioeconomic status and early childhood growth and nutrition in the PERSIAN Birth Cohort with insights into the double burden of malnutrition. Sci Rep 15, 14893 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97619-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97619-7