Abstract

Breast cancer ranks among the most prevalent cancers in women globally, with its treatment efficacy heavily reliant on the early identification and diagnosis of the disease. The importance of early detection and diagnosis cannot be overstated in enhancing the survival prospects of those afflicted with breast cancer. With the increasing application of machine learning technology in the medical field, algorithm-based diagnostic tools provide new possibilities for early prediction of breast cancer. In this study, we introduced a novel feature selection approach, which leverages Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) values as the basis for Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), utilizing a Random Forest (RF) algorithm within the RFE framework. To address the data imbalance challenge, we incorporated Borderline-SMOTE1. The efficacy of the proposed method was assessed using five machine learning models, K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Random Forest (RF), Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), applied to the Wisconsin Breast Cancer Diagnosis (WBCD) datasets. Optimizing hyperparameters of five models using the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm. In the datasets, 26 features were filtered using our recommended algorithm, the LightGBM-PSO model demonstrated an outstanding performance. The model demonstrated an impressive accuracy of 99.0% in differentiating between benign and malignant cases, boasting a specificity and precision of 100%, a recall rate of 97.40%, an F-measure of 98.68%, an AUC of 0.9870, and a 10-fold cross-validation accuracy of 0.9808. Subsequently, we developed a corresponding online tool (https://breast-cancer-prediction-tool-cgbjlhkns7yig6bmzvztmc.streamlit.app/) based on this model for predicting the risk of breast cancer. Feature selection using recommended algorithm and optimization of the LightGBM model through PSO can significantly enhance the accuracy of breast cancer prediction. This could potentially improve the prognosis for patients diagnosed with breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer among women worldwide1,2and the second leading cause of death among women3,4. The early stages of many breast cancers often present no noticeable symptoms. Consequently, the extraction and analysis of pertinent information from the vast data pool for the scientific evaluation of breast cancer is both complex and time-intensive5,6. This complexity poses significant challenges for early diagnosis, affecting both the treatment effectiveness and patient prognosis. Notably, accurate and early diagnosis substantially enhances the likelihood of patients receiving timely treatment, thereby reducing breast cancer mortality rates7,8.

Recently, many researchers have adopted diverse techniques for the early detection of breast cancer9, incorporating various machine learning algorithms into the WDBC dataset. Specifically, Tarek Khater et al.‘s k-nearest neighbors model10 reached a remarkable 97.7% accuracy and 98.2% precision for breast cancer classification using WDBC data. Masri Ayob et al.11 successfully employed a Fast Learning Network (FLN), attaining an impressive 98.37% accuracy on the WBCD database. Further reinforcing these findings, Sheng Zhou et al.12, through extensive experimentation with various machine learning models on the same dataset, highlighted the superior performance of AdaBoost-Logistic, exhibiting commendable classification capabilities for both benign and malignant cases. Deepa Kumari et al.13 achieved a 97% diagnostic accuracy by combining hybrid multi-layer perceptron (MLP) with random forest (RF), as well as Xception (a type of convolutional neural network) with RF. Indu Chhillar et al.14 successfully addressed class imbalance through Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique-Edited Nearest Neighbor (SMOTEENN) and employed Boruta and Coefficient-Based Feature Selection (CBFS) for robust feature selection, ultimately proposing a soft voting ensemble model. Their approach yielded an impressive 99.42% accuracy when utilizing the CBFS method. Vandana Rawat et al.15employed several ML algorithms for classification purposes and found that the Support Vector Machine algorithm delivered superior results. However, further explanation of the model is lacking, making it challenging for people to comprehend. To address the widespread issue of imbalanced learning, a common challenge for standard machine learning algorithms16, T. R. Mahesh et al.6implemented A-SMOTE for dataset balancing and achieved noteworthy outcomes. Nonetheless, A-SMOTE’s occasional selection of unsuitable samples as synthetics introduces noise that impairs the classification capability of the model. Feature selection is an essential step preceding classification tasks, particularly given the high dimensionality of biomedical datasets that frequently encompass irrelevant and redundant features17. In breast cancer research, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) has gained prominence as the preferred feature selection technique18,19. However, PCA synthesizes new components as linear combinations of the original features, potentially resulting in an information loss from the initial dataset. Furthermore, these newly formed features often pose challenges for an intuitive interpretation. Overall, challenges persist in areas such as dataset balancing, feature optimization, and model interpretability. The entire experimental process is shown in Fig. 1.

Materials and methods

Dataset

In this study, we used the publicly accessible Wisconsin Diagnostic Breast Cancer (WDBC) datasets (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/17/breast+cancer+wisconsin+diagnostic)20. The datasets comprised 569 samples, with a distribution of 357 benign and 212 malignant cases, all devoid of missing values. These features were extracted from digital images of breast mass fine-needle aspiration (FNA), which describes the characteristics of cell nuclei21.

Data preprocessing

Before employing machine learning (ML) for classification tasks, the data were subjected to a series of pre-processing steps22. Initially, min-max normalization was employed to normalize all feature values to a range between 0 and 1. Subsequently, the dataset was split 65:35 to train and test. Thereafter, to mitigate data imbalance in the training set, the Borderline Smote1 technique is applied23. The detailed process is shown in Fig. 2.

Shapley additive explanations (SHAP)

SHAP is a technique used to explain the predictions made by machine learning models24.

This method creates a framework for understanding by determining Shapley values, treating each feature as a “contributor.” In this framework, each feature is assigned a SHAP value in a specific set of predictors. These values show how much each feature contributes to the final prediction result. They also show whether each feature promotes or inhibits changes in the target variable and how each feature interacts with the target variable25,26. The mean absolute SHAP values across features are indicative of their respective importance. The calculation formula is as follows:

Each leaf node will contain a proper proportion of all possible subsets in the collection , where \(\:{S}_{j}\:\)is the feature subset that appears at leaf node j, is a subset of \(\:{S}_{j}\), \(\:{L}_{j}\) is the path length from the root node to leaf node j, (𝑤(|𝑃|,𝑗)) is the proportion of all subsets of at leaf node j, \(\:{p}_{o}^{i,j}\) and \(\:{p}_{z}^{i,j}\) represent the proportions of subsets that include and exclude feature i, respectively, and \(\:{\upsilon\:}_{j}\) is the output value of leaf node j .

SHAP-RF-RFE

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is an effective feature selection technique that systematically reduces feature set sizes via a recursive process27. In this study, we developed a unique algorithm, designated SHAP-RF-RFE, by integrating the Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) values with the Random Forest (RF) methodology within the RFE framework. This algorithm unfolds in a structured manner, as follows:

-

1.

Initially, a Random Forest classifier is trained using the available dataset.

-

2.

Subsequently, SHAP values for each feature are computed, quantifying their contribution to the prediction.

-

3.

The feature exhibiting the least SHAP value is then eliminated, signifying its minimal impact on the model’s predictive accuracy.

Machine learning models

The Random Forest (RF) algorithm is a sophisticated ensemble learning method. It comprises multiple distinct Decision Trees (DTs), each contributing to the final decision-making process. Unlike methods that depend on a single decision tree, RF aggregates the predictions from each tree, relying on the majority vote to formulate the ultimate prediction28,29. In this framework, each decision tree node executes splits based on the Gini Index, which is a measure of the statistical dispersion.

The Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a robust supervised learning model that is frequently employed to address classification and regression issues. Its fundamental premise is to identify an optimal hyperplane within the feature space that maximizes the distance between data points belonging to disparate categories, thereby facilitating effective classification18.

The logistic regression (LR) classification algorithm is a widely used tool in the field of machine learning. Its main goal is to predict the occurrence of an event by estimating probabilities, and it has the characteristics of easy implementation and strong interpretability of results30.

The K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) algorithm is a fundamental and pervasive classification and regression technique. Its working principle is simple and intuitive, mainly relying on measuring the distance between different feature points to perform classification or regression31.

LightGBM represents an advanced iteration of the Gradient-Boosted Decision Tree (GBDT) system32. LightGBM employs a histogram-based approach and leaf-wise growth strategy. This accelerates training and reduces the memory usage33,34. LightGBM retains data points with large gradients and down samples other data points while maintaining the essential characteristics of the data35. Given the typically sparse nature of high-dimensional data, this sparsity enables the formulation of a near-lossless method for feature-dimensionality reduction. In these sparse feature spaces, many features are often mutually exclusive and do not assume nonzero values simultaneously. LightGBM capitalizes on this by amalgamating these exclusive features into a single entity in a process called Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB).

Hyperparameter optimization

Metaheuristic algorithms demonstrate significant advantages in optimizing machine learning model parameters, particularly in handling large-scale, complex problems with no explicit gradient information. By mimicking natural search mechanisms, they facilitate effective global searches across extensive solution spaces, avoiding the pitfalls of local optima. Among metaheuristics, Genetic Algorithms (GA) stand out for simulating biological evolution processes using selection, crossover, and mutation to navigate the solution space, gradually refining candidate solutions toward optimality. Notable members include Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), GA, Differential Evolution (DE), Artificial Bee Colony (ABC), Firefly Algorithm (FA), the Coati Optimization Algorithm, and various hybrid intelligent algorithms36,37,38,39, which have found widespread applications in diverse domains such as healthcare, engineering, mathematics, and science40. This work focuses on Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) due to its merits: minimal parameter tuning requirements, high computational efficiency, robust performance, and ease of implementation for hyperparameter optimization. From analyzing bird flocking behavior, PSO is a collective intelligence optimization technique introduced by Kennedy and Eberhart et al.41. Its core principle is leveraging collaborative efforts and information sharing among particles to achieve optimal solutions. Fundamentally, PSO simulates the movement of a swarm of particles in the search space, continuously updating their positions and velocities until converging to the global optimum. Each particle maintains a position and velocity vector, and through iterative adjustments of these parameters, the swarm collectively identifies the best solution to the problem at hand42,43.

Performance assessment

Performance evaluation metrics include: accuracy, precision, recall, specificity, and F-measure; the ROC curve graphically displays the performance of the model at different thresholds; ten cross validations are used to evaluate the effectiveness and stability of the model on unseen data to enhance the understanding of the model’s performance44.

Results

The training and testing samples were run on a Windows 11 machine equipped with an i5 processor and NVIDIA RTX 2050. The model was implemented using Python 3.9. The data preprocessing was mainly performed using the ‘imblearn’ and ‘pandas’ libraries. The model development was carried out using the ‘nump’, ‘sklearn’, ‘shap’, and ‘scikit-opt’ packages. For the development of the online platform, the ‘streamlit’ package was employed.

The best machine learning model

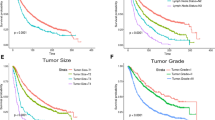

Initially, we employed and evaluated RF, SVM, LR, KNN, and LightGBM models to classify the WDBC dataset. Figure 3(a) shows the accuracy achieved by employing all the feature subsets ranging from 1 to 30. Figure 3(b) presents the AUC values and Fig. 3(c) shows the 10-fold cross-validation accuracy. After analyzing the accuracy of the five distinct models, it was observed that the LightGBM model generally surpassed the performance of the other models across most feature subsets. However, this model exhibits a slight decrease in accuracy compared with the others when the feature subsets include four, seven, ten, eleven, or twelve features. Remarkably, the accuracy of the LightGBM model reached 99.0% with a subset of 26 features. Moreover, a comparative analysis of the AUC values revealed that the LightGBM model typically outperformed the other models, achieving an AUC as high as 0.987 for the 26-feature subset. Nonetheless, the AUC values were marginally lower in smaller subsets of features 4, 7, 10, 11, and 12. The ten-fold cross-validation comparison of the accuracy rates for five models indicates that, within feature subsets ranging from 1 to 30, there is no significant difference among the LightGBM, KNN, and RF models. Conversely, the SVM and LR models generally exhibit weaker performance.

Subsequently, we evaluated the performance of RF, SVM, LR, KNN, and LightGBM models by selecting the model with the highest accuracy, AUC values, and ten-fold cross-validation accuracy from 30 models, each representing different feature subsets. Figure 4 displays the confusion matrices for the five best-performing models. Notably, the RF model with 28 features achieved a TP of 74, FN of 3, FP of 0, and TN of 123. The SVM model, equipped with 18 features, recorded a TP of 76, FN of 1, FP of 3, and TN of 120. Similarly, the LR model with 27 features showed a TP of 75, FN of 2, FP of 3, and TN of 120. The KNN model, with the least features at 12, excelled with a TP of 76, FN of 1, FP of 2, and TN of 121. The LightGBM model, with 26 features, demonstrated superior performance with a TP of 75, FN of 2, FP of 0, and TN of 123. Figure 5; Table 1 show the ROC curves and performance metrics of these models, highlighting the LightGBM model’s top accuracy of 99%, which is 0.5% higher than both the RF and KNN models, 1.0% higher than the SVM model, and 1.5% higher than the LR model. This model also excelled in specificity (100%), precision (100%), recall (97.40%), F-measure (98.68%), AUC (0.9870), and ten-fold cross-validation accuracy (0.9808). Table 2 details the optimized hyperparameters of the LightGBM model with 26 features, achieved through the PSO algorithm.

Distribution of importance of 26 features

In the SHAP-RF-RFE feature-selection algorithm, the average absolute SHAP values of each feature indicate their respective importance. Figure 6 illustrates the important distributions of these 26 features in the best-performing LightGBM model obtained using the SHAP-RF-RFE algorithm. The 26 features are ranked in order of importance from top to bottom. Notably, ‘radius_worst’, ‘area_worst’, and ‘perimeter_worst’ are deemed pivotal. The ‘radius_worst’ represents the radius of the largest cross-sectional area of the tumor. Generally, a larger radius signifies a larger tumor, which could potentially indicate a more aggressive form of cancer. The ‘area_worst’ refers to the area of the tumor’s largest cross-section. Typically, a larger tumor area implies a higher tumor load and may correlate with a higher degree of malignancy. ‘Perimeter_worst’ is the circumference of the tumor at its largest cross-section. The size of the perimeter mirrors the tumor’s morphology and the complexity of its growth. Generally, a longer perimeter may suggest a more irregular tumor morphology, which is often associated with a higher degree of aggressiveness and malignancy.

The interpretation of the model

In the subsequent analysis, the SHAP values were employed to interpret the LightGBM model, which integrates the previously mentioned 26 features. The SHAP swarm plot of this model is shown in Fig. 7, where positive SHAP values correlate with an increased probability of breast cancer diagnosis, whereas negative values suggest a decreased likelihood. To enhance visual comprehension, higher values were represented in red and lower values in blue. Notably, the feature with the most substantial impact on the model is ‘radius_worst.'A high value indicates an elevated risk of breast cancer, whereas a low value indicates a diminished risk. Conversely, ‘concavity_se’ emerges as the feature with the least influence on the model. Figure 7 shows that breast cancer risk is associated with the following 18 characteristics: radius_worst, texture_mean, area_worst, perimeter_worst, concave point s_worst, smoothness_worst, texture_worst, concavity_worst, concave points_mean, area_se, symmetry_worst, radius_se, smoothness_mean, concavity_mean, area_mean, perimeter_mean, fractal_dimension_worst, and compactness_worst. Conversely, lower values of these attributes imply reduced risk. For the subsequent five features, compactness_se, symmetry_se, concave points_se, fractal_dimension_se, and compactness_mean, the relationship was inverse; higher values correlated with a decreased likelihood of breast cancer, whereas lower values suggested an increased risk. Notably, for the symmetry_mean feature, a low value yielded an ambiguous prediction of the likelihood of breast cancer. For the radius_mean feature, a high value also yields an ambiguous prediction. However, the predictive value of concavity_se in breast cancer remains unclear.

Comparison with other models

Comparative analysis (detailed in Table 3) highlights the exceptional performance of our breast cancer prediction model, leveraging SHAP-RF-RFE for feature selection, LightGBM as the classifier, and PSO for hyperparameter tuning. Achieving remarkable accuracy (99%) and perfect precision (100%), our model surpasses counterparts in the literature, demonstrating superior predictive capability. While this high precision ensures no false positives, a slightly lower recall rate of 97.4% indicates potential under-detection of some actual cases. This integrated approach showcases strong predictive power and promising application potential for enhancing breast cancer diagnosis.

Discussion and conclusion

This study introduces a new breast cancer diagnostic model that is more accurate and efficient. We also use SHAP values to understand how the model makes decisions.

Breast cancer poses a significant public health concern and is also among the primary causes of mortality in women45,46. The early identification of breast cancer continues to be a pivotal focus in medical research. Traditionally, pathologists and radiologists are accustomed to manually observing breast images and reaching a consensus with other medical experts to make decisions and conduct analyses47,48. However, manually analyzing a large number of images used for diagnosing breast cancer is both laborious and time-consuming, which often may lead to false positive or false negative results49. Therefore, we need an automated system to improve analysis efficiency to assist radiologists in the early diagnosis of breast cancer50, where the role of machine learning in research is becoming increasingly vital. First, these algorithms analyze breast X-ray imagery, encompassing mammography, ultrasound, and MRI, to aid physicians in pinpointing potential lesions indicative of breast cancer51,52. Jia Li et al.53employed the Self-Attention Random Forest (SARF) model to classify breast X-ray images and achieved excellent accuracy. Second, through machine learning-driven analysis of extensive genomic data, researchers have delved into genetic mutations and biomarkers linked to breast cancer emergence, thereby facilitating the identification of genetic predispositions and crafting tailored preventive and therapeutic strategies54,55. Byung-Chul Kim et al.56constructed a high-accuracy model for predicting breast cancer metastasis using RNA-seq data and machine learning algorithms. Additionally, machine learning has been employed in the scrutiny of clinical patient data to discern potential risk factors and early indicators of breast cancer, utilizing both pathological findings and clinical histories to support more informed diagnostic and treatment decisions by medical professionals57,58. Mahendran Botlagunta et al.59proposed a machine learning-based web application that utilizes blood feature data for the early detection of breast cancer metastasis. The integration of machine learning into telemedicine systems enables real-time screening and diagnostic services for breast cancer, addresses disparities in medical resources, and enhances the accessibility and effectiveness of early detection efforts60.

Despite the impressive performance of our model, several limitations warrant consideration. Primarily, its generalization capability across diverse datasets requires further validation. While we achieved outstanding results on a specific dataset, applicability in other clinical settings or varied populations remains to be comprehensively assessed. Additionally, the model’s complexity may incur higher computational costs during practical deployment, posing challenges particularly in resource-constrained healthcare environments. Our research has culminated in a novel breast cancer prediction model, marked by significant accuracy, adaptability, and scalability improvements. To democratize access to this advanced technology, we have launched the “Breast Cancer Prediction Tool” (https://breast-cancer-prediction-tool-cgbjlhkns7yig6bmzvztmc.streamlit.app/), an intuitive online platform offering accessible risk assessment services. Patients and healthcare professionals can input relevant health data through a user-friendly interface to receive personalized risk evaluations instantaneously. This immediate feedback mechanism empowers early interventions and tailored treatment plans, supporting clinicians in making more informed and precise diagnoses and treatment decisions. Future work will encompass several key directions to enhance the robustness and applicability of our model. First, we aim to train the model on a more diverse set of datasets and integrate various imaging modalities to enrich the assessment of disease manifestations. Second, we plan to explore advanced optimization algorithms such as Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization (HPSO) and HPSO with Time-Varying Acceleration Coefficients (HPSO-TVAC)61. These techniques have demonstrated superior performance in tackling complex problems by efficiently converging towards optimal solutions, thereby boosting model accuracy62. Third, we intend to expand the scope of the model to predict the risk of other diseases such as lung cancer, thereby significantly enhancing its practical value.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available in the Wisconsin Diagnostic Breast Cancer datasets (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/17/breast+cancer+wisconsin+diagnostic). The data generated during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sukhadia, S. S., Muller, K. E., Workman, A. A. & Nagaraj, S. H. Machine learning-based prediction of distant recurrence in invasive breast carcinoma using clinicopathological data: a cross-institutional study. Cancers (Basel). 15 (15), 3960. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15153960 (2023).

Kode, H. & Barkana, B. D. Deep learning- and expert knowledge-based feature extraction and performance evaluation in breast histopathology images. Cancers (Basel). 15 (12), 3075. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15123075 (2023).

Khan, R. H. et al. A comparative study of machine learning algorithms for detecting breast cancer. 2023 IEEE 13th Annual Computing and Communication and (CCWC), 647–652 (2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/CCWC57344.2023.10099106

Huang, Z. & Chen, D. A breast cancer diagnosis method based on VIM feature selection and hierarchical clustering random forest algorithm. IEEE Access. 10, 3284–3293. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3139595 (2022).

Dehnavi, A. M., Sehhati, M. R. & Rabbani, H. Hybrid method for prediction of metastasis in breast cancer patients using gene expression signals. J. Med. Signals Sens. 3 (2), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.22038/jmss.2013.1115 (2013).

Mahesh, T. R. et al. B. Performance analysis of XGBoost ensemble methods for survivability with the classification of breast cancer. J. Sensors 4649510 (2022). (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4649510

Kourou, K., Exarchos, T. P., Exarchos, K. P., Karamouzis, M. V. & Fotiadis, D. I. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 13, 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2014.11.005 (2014).

Adebiyi, M. O., Arowolo, M. O., Mshelia, M. D. & Olugbara, O. O. A linear discriminant analysis and classification model for breast cancer diagnosis. Appl. Sci. 12, 11455. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122211455 (2022).

Chhillar, I. & Singh, A. An insight into machine learning techniques for cancer detection. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. B. 104, 963–985. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40031-023-00896-x (2023).

Khater, T. et al. An explainable artificial intelligence model for the classification of breast cancer. IEEE Access, 1–1 (2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.10099112

Albadr, M. A. A. et al. Breast cancer diagnosis using the fast learning network algorithm. Front. Oncol. 13, 1150840. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1150840 (2023).

Zhou, S., Hu, C., Wei, S. & Yan, X. Breast cancer prediction based on multiple machine learning algorithms. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 23, 15330338241234791. https://doi.org/10.1177/15330338241234791 (2024).

Kumari, D. et al. Predicting breast cancer recurrence using deep learning. Discov Appl. Sci. 7, 113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-025-06512-5 (2025).

Chhillar, I. & Singh, A. An improved soft voting-based machine learning technique to detect breast cancer utilizing effective feature selection and SMOTE-ENN class balancing. Discov Artif. Intell. 5, 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-025-00224-w (2025).

Rawat, V. et al. Supervised Learning Identification System for Prognosis of Breast Cancer. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 1–8 (2022). (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7459455

Li, J. et al. L. Adaptive swarm balancing algorithms for rare-event prediction in imbalanced healthcare data. PLoS One. 12 (7), e0180830. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180830 (2017).

Reddy, G. T. et al. Analysis of dimensionality reduction techniques on big data. IEEE Access. 8, 54776–54788. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2980942 (2020).

Khandaker, M. M. U., Biswas, N., Rikta, S. T. & Dey, S. K. Machine learning-based diagnosis of breast cancer utilizing feature optimization technique. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Update. 3, 100098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpbup.2023.100098 (2023).

Nanda Gopal, V., Al-Turjman, F., Kumar, R., Anand, L. & Rajesh, M. Feature selection and classification in breast cancer prediction using IoT and machine learning. Measurement 178, 109442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2021.109442 (2021).

Wolberg, W. H., Street, W. N. & Mangasarian, O. L. Machine learning techniques to diagnose breast cancer from image-processed nuclear features of fine needle aspirates. Cancer Lett. 77 (2–3), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3835(94)90099-x (1994).

Wolberg, W. H., Street, W. N., Heisey, D. M. & Mangasarian, O. L. Computerized breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis from fine-needle aspirates. Arch. Surg. 130 (5), 511–516. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430050061010 (1995).

Ogundokun, R. O., Misra, S., Douglas, M., Damaševiˇcius, R. & Maskeli¯unas, R. Medical Internet-of-Things based breast cancer diagnosis using Hyperparameter-Optimized neural networks. Future Internet. 14, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154337 (2022).

Han, H., Wang, W. Y., Mao, B. H. & Borderline, -SMOTE: A new Over-Sampling method in imbalanced data sets learning. In Advances in Intelligent Computing. ICIC 2005 Vol. 3644 (eds Huang, D. S. et al.) (Springer, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/11538059_91.

Lundberg, S. M., Erion, G. G. & Lee, S. Consistent Individualized Feature Attribution for Tree Ensembles. arXiv, abs/1802.03888 (2018).

Baehrens, D. et al. How to explain individual classification decisions. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 11, 1803–1831 (2010). http://arxiv.org/abs/0912.1128

Mohi Uddin, K. M., Biswas, N., Rikta, S. T., Dey, S. K. & Qazi, A. XML-LightGBMDroid: A Self-Driven interactive mobile application utilizing explainable machine learning for breast cancer diagnosis. Eng. Rep. 5 (11), e12666. https://doi.org/10.1002/eng2.12666 (2023).

Guyon, I. et al. Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach. Learn. 46, 389–422. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012487302797 (2002).

Chen, T. (ed Guestrin, C.) XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discovery Data Min. https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (2016).

Shafique, R. et al. Breast cancer prediction using fine needle aspiration features and upsampling with supervised machine learning. Cancers (Basel). 15 (3), 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030681 (2023).

Geng, Z. et al. Development and validation of a machine learning-based predictive model for assessing the 90-day prognostic outcome of patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Transl Med. 22 (1), 236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-04896-3 (2024).

A’la, F. Y., Permanasari, A. E. & Setiawan, N. A. A Comparative Analysis of Tree-based Machine Learning Algorithms for Breast Cancer Detection. In 2019 12th International Conference on Information & Communication Technology and System (ICTS), Surabaya, Indonesia, pp. 55–59 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTS.2019.8850975

Ke, G. et al. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. (2017).

Taha, A. A. & Malebary, S. J. An intelligent approach to credit card fraud detection using an optimized light gradient boosting machine. IEEE Access. 8, 25579–25587. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2983854 (2020).

Zheng, Y. J., Zhou, X. H., Sheng, W. G., Xue, Y. & Chen, S. Y. Generative adversarial network-based Telecom fraud detection at the receiving bank. Neural Netw. 102, 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2018.02.015 (2018).

Yao, X., Fu, X. & Zong, C. Short-Term load forecasting method based on feature preference strategy and LightGBM-XGBoost. IEEE Access. 10, 75257–75268. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3192011 (2022).

Abd Elaziz, M., Dahou, A., Mabrouk, A., El-Sappagh, S. & Aseeri, A. O. An efficient artificial rabbits optimization based on mutation strategy for skin cancer prediction. Comput. Biol. Med. 163, 107154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107154 (2023).

Pethe, Y. S. et al. FSBOA: feature selection using Bat optimization algorithm for software fault detection. Discov Internet Things. 4, 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43926-024-00059-4 (2024).

Książek, W. Explainable thyroid cancer diagnosis through Two-Level machine learning optimization with an improved naked Mole-Rat algorithm. Cancers (Basel). 16 (24), 4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16244128 (2024).

Alshardan, A. et al. Transferable deep learning with Coati optimization Algorithm-Based mitotic nuclei segmentation and classification model. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 30557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80002-3 (2024).

Pałka, F., Książek, W., Pławiak, P., Romaszewski, M. & Książek, K. Hyperspectral classification of Blood-Like substances using machine learning methods combined with genetic algorithms in transductive and inductive scenarios. Sens. (Basel). 21 (7), 2293. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21072293 (2021).

Kennedy, J. & Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. Proceedings of ICNN’95 - International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 4, 1942–1948. (1995). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICNN.1995.488968

Deng, W., Xu, J., Zhao, H. & Song, Y. A novel gate resource allocation method using improved PSO-based QEA. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 1737–1745. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2020.3025796 (2022).

Liu, J., Yang, D., Lian, M. & Li, M. Research on intrusion detection based on particle swarm optimization in IoT. IEEE Access. 9, 38254–38268. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3063671 (2021).

Su, W. et al. iRNA-ac4C: A novel computational method for effectively detecting N4-acetylcytidine sites in human mRNA. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 227, 1174–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.11.299 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Development and validation of a radiopathomic model for predicting pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 23, 431. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10817-2 (2023).

Zhu, K. et al. Application of serum mid-infrared spectroscopy combined with machine learning in rapid screening of breast cancer and lung cancer. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2023, 4533108. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4533108 (2023).

Feng, C. et al. Prediction of trust propensity from intrinsic brain morphology and functional connectome. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25215 (2021).

Shah, S. M., Khan, R. A., Arif, S. & Sajid, U. Artificial intelligence for breast cancer analysis: trends & directions. Comput. Biol. Med. 142, 105221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105221 (2022).

Fatima, M. et al. B2C3NetF2: breast cancer classification using an end-to-end deep learning feature fusion and satin Bowerbird optimization controlled Newton Raphson feature selection. CAAIT Trans. Intell. Technol. 8, 1374–1390. https://doi.org/10.1049/cit2.12219 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. DE-Ada*: A novel model for breast mass classification using cross-modal pathological semantic mining and organic integration of multi-feature fusions. Inf. Sci. 539, 461–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2020.05.080 (2020).

Liang, H. et al. Mammographic classification of breast cancer microcalcifications through extreme gradient boosting. Electronics 11, 2435. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11152435 (2022).

Li, X. et al. A comprehensive review of computer-aided whole-slide image analysis: from datasets to feature extraction, segmentation, classification and detection approaches. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55, 4809–4878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-021-10121-0 (2022).

Li, J., Shi, J., Chen, J., Du, Z. & Huang, L. Self-attention random forest for breast cancer image classification. Front. Oncol. 13, 1043463. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1043463 (2023).

Nicora, G., Vitali, F., Dagliati, A., Geifman, N. & Bellazzi, R. Integrated multi-omics analyses in oncology: A review of machine learning methods and tools. Front. Oncol. 10, 1030. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01030 (2020).

Cai, Z., Poulos, R. C., Liu, J. & Zhong, Q. Machine learning for multi-omics data integration in cancer. iScience 25, 103798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.103798 (2022).

Kim, B. et al. Machine learning model for lymph node metastasis prediction in breast cancer using random forest algorithm and mitochondrial metabolism hub genes. Appl. Sci. 11 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Label-free detection of rare Circulating tumor cells by image analysis and machine learning. Sci. Rep. 10, 12226. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69056-1 (2020).

Wen, J. et al. Prognostic significance of preoperative Circulating monocyte count in patients with breast cancer: based on a large cohort study. Med. (Baltim). 94, e2266. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002266 (2015).

Botlagunta, M. et al. Classification and diagnostic prediction of breast cancer metastasis on clinical data using machine learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 13, 485. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27548-w (2023).

Al-Hejri, A. M. et al. Ensemble self-attention transformer encoder for breast cancer diagnosis using full-field digital X-ray breast images. Diagnostics (Basel). 13, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13010089 (2022).

Sun, C., Zhao, H. & Wang, Y. A comparative analysis of PSO, HPSO, and HPSO-TVAC for data clustering. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 23, 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/0952813X.2010.506287 (2011).

Yin, B. et al. Prediction of tunnel deformation using PSO variant integrated with XGBoost and its TBM jamming application. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 150, 105842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.105842 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Basic Research Project of Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau in 2022 under Grant 202201011668, in part by the second batch of the Industry-University Cooperation Collaborative Education Project of the Ministry of Education in 2018 under Grant 201802212018, and in part by the Hunan Provincial Scientific Research Program of Traditional Chinese Medicine under Grant 2021110.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(I) Conception and design: Rong Chen, Youde Ding; (II) Data analysis and interpretation: Jing Zhu, Zhenhang Zhao; (III) Manuscript writing: All authors; (IV) Final approval of the manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, J., Zhao, Z., Yin, B. et al. An integrated approach of feature selection and machine learning for early detection of breast cancer. Sci Rep 15, 13015 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97685-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97685-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Electromagnetic field confinement-driven multi-resonator THz biosensing platform with Au–Ag–graphene hybrid coatings and angle-invariant machine learning prediction for point-of-care breast cancer diagnostics

Microsystem Technologies (2026)

-

Designing novel FAK inhibitors targeting gastric cancer: a combined approach using machine learning, docking analysis, molecular dynamics simulations, and experimental validation

Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design (2026)

-

Optimized breast cancer diagnosis using self-adaptive quantum metaheuristic feature selection

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Breast cancer classification based on microcalcifications using dual branch vision transformer fusion

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Multimodal Breast Cancer Classification Using Fractional-Order Three-Triangle Multi-delayed Neural Network Optimized with Hunger Games Search

Biomedical Materials & Devices (2025)