Abstract

Leprosy is an infectious and chronic dermatoneurological disease, considered the most frequent cause of physical disabilities worldwide. It remains a major challenge for public health in Brazil, which is classified as a country with a high burden of the disease and ranks second in number of cases among all nations. Laboratory tests are important tools to complement the clinical-epidemiological evaluation, and molecular techniques emerged in the hope of reducing the limitations existing in the laboratory diagnosis of leprosy. We aimed to evaluate the accuracy of real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in the detection of Mycobacterium leprae in direct intradermal scrapings (swabs) and smears from bacilloscopy slides. This is an observational and cross-sectional study to evaluate diagnostic tests, which used bacilloscopy as the gold standard. Participants with epidemiological and/or clinical suspicion of leprosy from the northeastern region of Minas Gerais, referred to the Macroregional Laboratory of Teófilo Otoni for collection of intradermal scrapings from the earlobes, right elbow, left elbow or suspicious lesion were included. Bacilloscopy was performed according to the Technical Procedures Guide of the Ministry of Health and the DNA samples, after extraction and quantification, were subjected to qPCR with primers specific for the RLEP region of Mycobacterium leprae. The study obtained the number of 45 samples collected from suspected cases of leprosy in the period between May/2022 and February/2023. Descriptive, comparative and accuracy statistical analyses were performed using Minitab 17 and GraphPad Prism version 6.00 software. The sensitivity of qPCR on direct intradermal scraping samples (swabs) and smear slides, compared with bacilloscopy, was 100%. The specificity was higher for qPCR on swab samples (64.3%) than on smear slides (53.8%). The performance of qPCR on intradermal scraping swab samples and smear slides indicated accuracies of 82.10 and 76.9%, respectively. The results of the comparison of the proportions of qPCR positivity of the two samples showed a statistically significant association (P-value = 0.005), with a degree of agreement of 55% (Kappa = 0.55). Taken together, the results of the performance and comparative analyses of qPCR on intradermal scraping swabs and smear slides showed good accuracy in relation to bacilloscopy and moderate agreement between these different qPCR strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

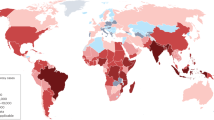

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by an acid-fast bacillus Mycobacterium leprae or Mycobacterium Lepromatosis1. The number of new cases of leprosy recorded in 2022 was 174,087 worldwide, representing a reduction of 19.3% since 20132. Most cases in 2022 were found in India. Brazil and Indonesia have also reported high incidences of leprosy3.

Despite being curable, leprosy remains endemic in several regions of the world and is strongly associated with poverty and socioeconomic conditions. It remains a major challenge for public health in Brazil, which is classified as a country with a high burden of the disease, reporting 18,318 new cases in 2021 and ranking second among the nations with the highest number of cases in the world4. In the state of Minas Gerais, some indicators, such as the detection of new cases in children under 15 years of age and new cases with grade 2 physical disability, point to a worrying epidemiological scenario, especially in the municipalities under the jurisdiction of the Teófilo Otoni Regional Health Superintendence (SRS-TO), which has a detection rate of new cases per 100,000 inhabitants more than three times higher than the state average5,6.

The inability to cultivate M. leprae in vitro and the lack of solid experimental models limit the deepening of knowledge about the disease. Furthermore, there is still no specific vaccine for leprosy. Given these obstacles, the most effective way to combat the disease is through early diagnosis and, consequently, correct and timely treatment, thus interrupting the chain of transmission7,8,9,10.

An early and assertive diagnosis is essential for controlling leprosy and achieving the World Health Organization’s (WHO) ambitions of interrupting transmission and eliminating indigenous cases by 2030. However, late diagnosis is very common in Brazil, which leads to an increase in disabilities and deformities that could be avoided if treated with specific drugs at the right time. Furthermore, incorrect diagnoses can lead to under- or over-treatment, intensifying relapses and leprosy reactions10,11.

The wide variety and peculiarities of clinical forms, the long incubation period and the small number of symptoms in the initial phase of the disease impact the speed of identification of new cases and diagnostic errors or underdiagnosis. In this context, laboratory tests are important tools for complementing the clinical-epidemiological diagnosis, classifying clinical forms for establishing treatment, and for differentiating them from other dermatological and neurological diseases, suspected recurrence or other situations of doubt10.

The most commonly used laboratory test is intradermal smear microscopy, which, despite being a test with high specificity and low cost, has low sensitivity. The detection and genomic sequencing of M. leprae due to the development of molecular techniques emerged in the expectation of reducing the limitations existing in the laboratory diagnosis of leprosy. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method that allows the detection of bacillus genetic material in very low concentrations and in different types of samples, presenting itself as a promising method in difficult-to-diagnose situations and in the early identification of the disease10,12,13,14.

Given the need to seek more accurate laboratory tests that can favor a more assertive and early diagnosis, aiding in the control and prevention of physical disabilities resulting from leprosy, this study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of PCR methods in samples collected from intradermal scrapings, analyzed at the Macroregional Laboratory of Teófilo Otoni (LMTO) and the Molecular Biology Laboratory of the Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys (UFVJM), Mucuri campus.

Methods

Institute approvals

The study was duly registered on the Plataforma Brasil and approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Fiocruz Minas, Federal University of the Jequitinhonha e Mucuri Valleys and all participating institutions, under number (CAAE): 53295521.8.0000.5091. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). The protection of participants was a priority for this study. To this end, the research team followed guidelines for Good Practices in Clinical Research and strictly complied with Resolution No. 466/2012 of the National Health Council. The research was conducted in Brazil, in the health area, and did not have access to genetic heritage, in compliance with the Biodiversity Law (Law 13,123).

Study design and setting

This is an observational and cross-sectional study to evaluate diagnostic tests, carried out in municipalities under the jurisdiction of the Regional Health Superintendence of Teófilo Otoni (SRS-TO). It is part of the Longitudinal Study of Hansen’s Disease in the Mucuri Valley (ELOHA) project, in a post-COVID-19 context.

The ELOHA project is proposed by the René Rachou Institute—Fiocruz MG, in partnership with the SRS-TO, the Municipal Health Department of Teófilo Otoni (SMS-TO) and the Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys (UFVJM), in Mucuri Campus, in a study that investigates the epidemiological, clinical and laboratory aspects of new cases of Hansen’s Disease and their contacts in the Mucuri Valley, Minas Gerais.

Participants

This project proposed the inclusion of participants with epidemiological and/or clinical suspicions of Hansen’s disease, after signing the Free and Informed Consent Form, who were referred to the Dr. Roberto Schuffner Polyclinic, of the Municipal Health Department of Teófilo Otoni or directly to the LMTO, through the health services of the other cities belonging to the SRS-TO. Laboratory tests were performed at the Macroregional Laboratory and at the Molecular Biology Laboratory of UFVJM, Mucuri campus.

Sample size

Considering the annual average of 1,000 new cases of leprosy and the average general detection rate of 5%, in the period 2016 to 2019, in the state of Minas Gerais, which has a population of 21,000,000 inhabitants, the sampling procedure was carried out, with a final number of 45 for the 90% CI.

Procedures performed

Intradermal smear collection

According to the Technical Procedures Guide: Bacilloscopy in Hansen’s Disease14, in visible skin lesions or areas with altered sensitivity in new cases, lymph was collected for intradermal smear from the following sites: right earlobe, left earlobe, right elbow and lesion. In patients who do not have visible active lesions, lymph will be collected from the right earlobe, left earlobe, right elbow and left elbow.

Immediately before collection, antisepsis was performed with 70ºGL or 70% alcohol, of the indicated sites. Then, with the aid of Kelly forceps, a fold was made at the collection site, pressing the skin enough to obtain ischemia, avoiding bleeding, a small cut was made in the skin approximately 5 mm long by 3 mm deep, to perform intradermal scraping of the edges and bottom of the incision, removing a sufficient and visible quantity of material (approximately 4 µL from each site) for mounting the slides.

Bacilloscopy

The slides were fixed by passing them three times through the flame of a Bunsen burner, with the smears facing upwards. They were stained using the Ziehl–Neelsen method in cold water, covering the smears with the fuchsin solution, previously filtered, for 20 min. After this step, the slides were washed in running water under low pressure and, subsequently, decolorized with a 1% acid-alcohol solution. They were washed again in running water under low pressure and the smears were covered with a 0.3% methylene blue solution for 1 min. They were washed in running water and left to dry at room temperature. An optical microscope was used to read the slides with an immersion objective (100 × magnification) and 10 × eyepiece. All procedures, from collection to reading the slides, were performed at the LMTO (Fig. 1).

Detection and quantification of Mycobacterium leprae by qPCR

Simultaneously with the collection of intradermal scrapings/lymph for bacilloscopy, in each of the four previously indicated sites, swabs were introduced into the surgical incisions and were soaked with a residual volume of lymph (approximately 2 µL from each site), packaged in 2 ml microtubes and stored in an ultra-freezer for conservation at − 80 °C. In addition to these samples, the study also used the material from the smears of the bacilloscopy slides. The material was scraped using a sterile scalpel and transferred to 1.5 mL tubes, as described by Castro et al.15, and stored at room temperature.

In a second step, after obtaining the necessary sampling for the study, the samples were subjected to qPCR testing, following the following steps:

Extraction of M. leprae DNA from swabs and slides

Extraction was performed using the PureLink® Genomic DNA Kits (Invitrogen) with modifications. The swabs were placed in 1.5 ml tubes and 500 µL of digestion buffer and 40 µL of Proteinase K (20 mg/ml) were added for complete coverage. They were then vortexed for 15 s and incubated in a dry bath at 55 °C for 30 min, with the tubes being vortexed for 15 s every 5 min. The swab was discarded with sterile forceps and 200 µL of lysis buffer and 200 µL of absolute ethanol were added to the supernatant, with each addition being vigorously vortexed. The contents of the tubes were transferred to the kit’s extraction columns and centrifuged at 13,000 rotations per minute (rpm) for 1 min. The filtrate was discarded, 500 µL of wash buffer I were added to the columns and centrifuged again at 13,000 rpm for 1 min. The tube with the filtrate was discarded and the column placed in a new collection tube. Next, 500 µL of wash buffer II were added, and the columns with the tubes were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 min. The collection tubes were discarded and the column placed in a 1.5 ml tube. 40 µL of elution solution were added to the columns, followed by incubation at room temperature for 5 min. After this period, the columns with the tubes were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 1 min. The eluate obtained was stored at − 20 °C until use.

In the case of smears from bacilloscopy slides, the protocol was followed exactly as with swabs, except that the elution volume was 30 µL.

DNA quantification

Quantification was performed using the Quantifluor One DNA kit (Promega Incorporation), following the manufacturer’s instructions. For this, 2 µL of the sample were incubated with 200 µL of the kit reagent, incubated for 5 min at room temperature, protected from light and read on the Quantus fluorimeter (Promega Incorporation). The concentrations were expressed in ng/µL and were used for dilution of the samples and application in the following analyses.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The DNA samples were subjected to PCR with primers specific for the RLEP region of M. leprae, and for the constitutive Beta Actin gene. The primers were purchased from the manufacturer Intergrated DNA Technologies (IDT, USA) (Table 1).

The assays for detection of M. leprae were performed in duplicates using 5 ng of total DNA in Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix [2 X] (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), containing 0.5 uM of each primer in a total volume of 12 µL. The reactions were performed in the CFX96TM Touch Real Time PCR Systems thermocycler (BioRad, USA) and the analyses in the CFX Maestro software (BioRad, USA). The thermocycling reactions consisted of: 2 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 62.5 °C and 1 min at 72 °C. At the end, a 20-min cycle was performed varying the temperature between 65 and 95 °C, with increments of 0.5 °C to obtain the melting curve, which was used to analyze the specificity of the amplification products. The samples were analyzed for the first fluorescence signal detected by the device, expressed as Cycle Threshold (CT), and samples were considered positive when they had CT ≤ 37. The constitutive/endogenous control gene Beta-actin was used as a sample quality control, therefore, samples that did not amplify the gene or amplified with CT > 37 were classified as Low Quality Samples (LQS) and will not be included in the accuracy analyses.

Standard curve and detection limit

To evaluate the detection limit of the method, a standard curve was prepared using a clinical sample, known to be positive and high BI (5.75). The sample was extracted, according to the protocol described above, and assayed for total DNA levels. The curve consisted of 7 points and was performed by serial dilution (1:10), with the initial and final points of 5 ng and 5 fg, respectively. Curve tests were performed at different times to confirm the reproducibility and correlation of CT with the amounts of M. leprae DNA. The detection limit was considered the amount of DNA detectable up to CT 37.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive, comparative and accuracy statistical analyses were performed using Minitab 17 and GraphPad Prism version 6.00 software. For comparative analyses, Student’s t-test was used for parametric data and the chi-square test for nonparametric data. ROC curves were used to assess the accuracy of the tests. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Table 2 shows the results obtained in the bacilloscopy that was filled in on SINAN. The information was filled in incorrectly in 60% of the positive bacilloscopy tests and in 58.8% of the negative ones, with the fields not performed and not reported being filled in. Regarding the analysis of the results of the qPCR tests of the intradermal swab samples and the smears on slides, out of 45 possible samples, 06 swab samples and 28 slides samples were classified as LQS, as they did not amplify the Beta-actin gene or amplified with CT > 37. These low-quality samples were discarded from the accuracy analyses.

Regarding the analysis of the results of the qPCR tests on the intradermal swab samples and smears on slides, out of 45 possible samples, 06 swab samples and 28 slides samples were classified as LQS, as they did not amplify the Beta-actin gene or amplified with CT > 37. These low-quality samples were discarded from the accuracy analyses.

The Figs. 2 and 3 express the results of the bacilloscopy tests performed at the LMTO, the classification as to whether or not they were reported in SINAN, and the results of the qPCRs, swabs, and smears on slides, performed in the molecular biology laboratory of UFVJM, Mucuri campus.

Of the samples that were analyzed using both methods, 28.2% were positive in bacilloscopy and 53.8% in qPCR. All samples with positive bacilloscopy, from cases or suspects, reported or not in SINAN, obtained a positive result for the qPCR test, that is, there was amplification and detection of genetic material of M. leprae in 100% of the samples. Adding the samples from cases or suspects reported and not reported in SINAN with negative bacilloscopy, we found 35.7% positivity in the qPCR test. When only unreported cases with negative bacilloscopy are taken into account, the percentage of samples with positive qPCR reaches 41.7% of the samples.

The diagram in Fig. 3, with the bacilloscopy and qPCR analyses of the slides, shows that 23.5% were positive in bacilloscopy and 58.8% in molecular biology. As occurred in the analyses of the samples collected with the swab, all samples with positive bacilloscopy obtained amplification and detection of M. leprae genetic material. For the samples with negative bacilloscopy, we found a positivity of 46.2% in the qPCR test. A negative point was the large number of LQS (28) that were excluded from the accuracy analyses. It was noteworthy that, of the 11 samples with positive bacilloscopy, 9 amplified and detected M. leprae genetic material, but of these, 5 did not amplify, or amplified with CT > 37, the quality control gene Beta-actin. It should be noted that the average concentration (4.27 ng/µl) of DNA extracted from the swabs was substantially higher than the average concentration (1.50 ng/µl) of DNA extracted from the slides.

The performance of both the qPCR of the intradermal smear and the qPCR of the smear microscopy slide, in comparison with the bacilloscopy, are summarized in Table 3. The sensitivity of qPCR on direct intradermal scrapings (swabs) and smear slides, compared with sputum smear microscopy, was 100%. The specificity was higher for qPCR on swab samples (64.3%) than on smear slides (53.8%). Considering the prevalence rate of leprosy in the study region of 2.02%, positive predictive values of 5.40 and 4.97, respectively, were observed for qPCR on intradermal scrapings swabs and smear slides.

The negative predictive values were 100% for both qPCR strategies. Taken together, the performance of qPCR on swab samples and smear slides indicated accuracies of 82.10% and 76.9%, respectively. These performance results can also be observed in the qPCR ROC curves (Fig. 4).

The results of the comparison of the qPCR positivity proportions in intradermal scrapings and smear microscopy slides are described in Table 4.

The results of the comparison of the proportions of qPCR positivity in intradermal scraping swabs and sputum smear slides show a statistically significant association (P-value = 0.005), with a degree of agreement of 55% (Kappa = 0.55). Taken together, the results of the performance and comparative analyses of qPCR in intradermal scraping swabs and sputum smear slides show good accuracy in relation to sputum smear and moderate agreement between these different qPCR strategies.

Discussion

All participants in our study who tested positive in the sputum smear microscopy had M. leprae genetic material detected in their samples, i.e., the qPCR had 100% agreement with the laboratory test used as the gold standard. In a study conducted in Nepal, which made a comparative evaluation of molecular biology and sputum smear microscopy in a cohort of new leprosy cases diagnosed at the BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, in the city of Dharan, using the same target as our study (RELP)16, a 100% agreement was also observed in the samples with positive sputum smear microscopy. For the samples negative in sputum smear microscopy, they found a positivity of 66%, while in ours it was 35.7%17.

In the Nepalese study, as well as in the Indian one, all participants were clinically confirmed cases of leprosy (inclusion criterion). In our research, it was enough to have clinical and/or epidemiological suspicion to be included as a participant, therefore, non-sick individuals may have been part of our sample, which could explain a lower positivity in the qPCR test. However, because our study allowed both confirmed and suspected participants, we reached extremely relevant results regarding leprosy surveillance. Continuing the discussion of the diagram with the results of the analyses, we highlight the suspects not reported in SINAN with negative bacilloscopy, but 41.7% of the samples presented positive results in the qPCR. These are individuals who were not diagnosed with leprosy by health services, until the time the SINAN data were extracted, and who had genetic material of M. leprae detected in their samples.

In the study by Pinheiro18 that used the same molecular biology test (qPCR) and the same genetic target (RLEP) as our research, 47.43% of the unreported suspects obtained positive results in the test. These findings are extremely relevant and make us reflect on some points. They could be suspected with very subtle and/or nonspecific symptoms, combined with the lack of expertise of the professional who evaluated them. It could be the incorrect use of the bacilloscopy exam to define the diagnosis, and there could also be operational failures in the notification, as identified in the sample of this study. These data suggest that possible infected individuals are undiagnosed, untreated and may be transmitting the bacillus, since, according to Goulart and Goulart19, there is evidence that transmission can occur even in subclinical infection.

As shown in Fig. 2, the analyses of the bacilloscopy and qPCR of the samples extracted from the slides, presented results similar to those expressed in the diagram in Fig. 3, with the qPCR analyses of the swab samples, obtaining 23.5% positivity in the bacilloscopy and 58.8% in molecular biology.

We found a small number of studies (04) in the literature with the purpose of performing PCR tests on samples extracted from intradermal scrapings. In the study by Maia20, of 228 slides from patients previously diagnosed with leprosy, 43 (18.8%) samples presented positive bacilloscopy, while PCR analyses reached 173 (75.9%) positivity.

In the swab and slide analyses of this study, all samples with positive bacilloscopy obtained amplification and detection of the genetic material of M. leprae. In the studies by Azevedo et al. 21, who also used qPCR, and by Turankar et al.22, who used conventional PCR, the positivity of the molecular biology tests was 84% and 83%, respectively, in the samples extracted from intradermal scraping slides.

For samples with negative bacilloscopy, this study detected a positivity of 46.2% in the qPCR examination of the slides, in general. In similar studies, which used the RLEP target in samples extracted from scraping slides, they obtained 53% and 30% positivity in negative bacilloscopy. However, unlike our analyses, the negative slides in these studies were from confirmed cases of leprosy. Our sample included cases and suspects (not reported) with negative bacilloscopy, which reached 40% and 50% positivity in qPCR, respectively21,22.

In our study, of the 11 slides with positive bacilloscopy, 11 amplified and detected M. leprae genetic material in the qPCR of the swabs and 9 in the qPCR of the slides. However, it is worth mentioning that only 4 samples from the slides were included in the accuracy analyses, since the other 7 did not amplify, or amplified with CT > 37, the quality control gene Beta-actin and were considered LQS. According to Ruiz-Fuentes et al.23, the amplification of target sequences depends on several factors, among which the quantity and quality of the nucleic acids extracted from the samples stands out. The average concentration (1.50 ng/µl) of DNA extracted from the slides was considerably lower than that from the swabs (4.27 ng/µl), which may be the probable cause of the higher number of LQS.

It is worth noting that the genetic material extracted from sputum smear slides underwent preliminary fixation, staining and use of immersion oil, which may have affected the quality of the DNA. In a study that compared four DNA extraction methods for the detection of M. leprae in Ziehl–Neelsen-stained microscopic slides, a common pretreatment step was included with the use of xylene to remove excess immersion oil, in addition to proteinase K and 10% sodium lauryl sulfate23,24. In our study, we used an extraction technique similar to that of Castro et al. 15 in which the samples were extracted from direct diagnostic slides for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. The performance of qPCR of direct intradermal scrapings (swabs) and slides, compared with bacilloscopy, established a sensitivity of 100% in both, and the specificity was higher in qPCR of swab samples (64.3%) than in bacilloscopy slides (53.8%). The set of analyses indicated an accuracy of 82.1% for qPCR of swabs and 76.9% for slides.

We emphasize that the objective of this study was not to make comparisons based on the disease, but rather on diagnostic strategies, using the bacilloscopy technique as the gold standard. Therefore, the study is comparing bacilloscopy and molecular biology (qPCR), both with specimens collected from the same sites. Furthermore, the samples for the qPCR test were obtained from two different techniques, one collected directly by swab and the other by extracting material from the slides used in bacilloscopy. The accuracy achieved in the qPCR of swabs and slides means that there was a hit rate of 82.1% and 76.9%, respectively, in relation to the gold standard test.

The accuracy performance can also be observed in the analysis of the ROC curves. Comparing the discriminative capacity of two or more diagnostic tests is one of the purposes of the ROC curve, which offers a statistical method to evaluate accuracy. For this purpose, the tests to be compared need to be measured simultaneously, performed on the same individuals and compared with the same gold standard, requirements that were met in this study25.

In our observation, limitations were identified, especially in the negative diagnosis of bacilloscopy, which becomes positive in the qPCR test. It is important to note that the gold standard (smear microscopy) used to assess the accuracy of qPCR in this study is a test with high specificity, but with low sensitivity, impacting false-negative diagnoses. In most of the studies we found, the samples came from confirmed cases of leprosy, diagnosed through clinical-dermatoneurological examinations. In these studies, when comparing the performance of smear microscopy and molecular biology examinations, they show a greater sensitivity of PCR. While slides stained by Ziehl Neelsen require the presence of at least 10,000 bacilli/mL of sample, molecular biology examinations allow the amplification and detection of the target being investigated from a very small amount of particles of genetic material21,26. In other words, this statistical error found in the analyses corroborates the evidence found in the literature regarding the greater probability of PCR diagnosing cases that would be negative in the bacilloscopy exam10,12,13,27.

Another piece of data from the study that reinforces this rationale are the cases diagnosed with leprosy and reported to SINAN that obtained a negative result in the bacilloscopy, but that amplified and detected genetic material of M. leprae. There were 05 (31.3%) in the qPCR of swabs and 2 (40.0%) in the qPCR of slides.

The agreement index of the Kappa coefficient of the qPCR analyses of the swabs and bacilloscopy slides was 0.55, which means moderate agreement. The Chi-square showed a significant statistical association between the methods, that is, one test can replace the other. The results of this study confirm that molecular biology testing (PCR) may be of significant value in laboratory diagnostic strategies for leprosy and are in line with the analyses of scientific evidence described in Recommendation Report No. 690 of the National Commission for the Incorporation of Technologies into the Unified Health System (SUS)10, on the performance of qPCR molecular biology tests for the qualitative detection of M. leprae for the diagnosis of leprosy, which culminated in the incorporation of the test into the SUS10.

Given the greater sensitivity of the PCR test compared to bacilloscopy, a possible model for introducing this test in the diagnosis of suspected leprosy is the one used in laboratory surveillance of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) in the state of Minas Gerais, which uses serial tests, starting with a smaller one, to a more sensitive test. In this model, suspected cases of the disease first undergo direct parasitological diagnosis (DPD). In the case of a positive case, a confirmed case of CL, but if the DPD result is negative and clinical suspicion persists, a biopsy sample should be sent to FUNED for PCR. Adapting this model for the diagnosis of leprosy, suspected cases would undergo bacilloscopy, and if negative, they would undergo the PCR test, which would be another tool for the complex diagnosis of the disease and would increase the probability of detecting cases with infections without apparent and/or doubtful signs28.

The instructional material produced in this research with information on leprosy will be another tool that will assist in technical training and, as it is a web platform, it can be easily consulted by health professionals, students and others interested in the subject. There is consensus in the literature that health professionals must receive continuous theoretical and practical training, therefore, this and other health education initiatives are essential for the effective control of leprosy29.

Conclusion

Leprosy is an infectious and chronic dermatoneurological disease considered the most frequent cause of physical disabilities worldwide. It remains a significant challenge for public health in Brazil, which is classified as a country with a high disease burden and ranks second in the number of cases among all nations.

This study included participants with epidemiological and/or clinical suspicion of leprosy from the northeastern Minas Gerais region, precisely Teofilo Otoni city, which presents a high prevalence of leprosy in the Minas Gerais State of Brazil; the authors standardized a method for less invasive samples with great potential to aid in case identification. The technique can be validated, and, subsequently, its cost-effectiveness can be assessed so that, ultimately, it can be indicated that this test should be incorporated into leprosy diagnostic strategies.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Change history

17 June 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07133-z

Abbreviations

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- BI:

-

Bacilliferous Index

- CL:

-

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

- CT:

-

Cycle Threshold

- DPD:

-

Direct Parasitological Diagnosis

- ELOHA:

-

Longitudinal Study of Leprosy in the Mucuri Valley (in Portuguese)

- FUNED:

-

Ezequiel Dias Foundation (in Portuguese)

- LMTO:

-

Macroregional Laboratory of Teófilo Otoni (in Portuguese)

- LQS:

-

Low Quality Samples

- PCR:

-

Polimerase Chain Reaction

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

- RLEP:

-

Specific Repetitive Element

- ROC:

-

ReceiverOperating Characteristic Curve

- RPM:

-

Rotations per minute

- SINAN:

-

Notifiable Diseases Information System (in Portuguese)

- SES:

-

State Health Secretariah (in Portuguese)

- SMS:

-

Municipal Health Secretariah (in Portuguese)

- SRS:

-

Regional Health Superintendence (in Portuguese)

- SUS:

-

Unified Health System (in Portuguese)

- UFVJM:

-

Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys (in Portuguese)

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Ferreira, P. M., Rato, I. R., Rigor, J. & Mota, M. Hansen’s disease - A forgotten disease?. JRSM Open. 12(8), 20542704211035996. https://doi.org/10.1177/20542704211035995 (2021).

Leprosy - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization. https://www.paho.org/en/topics/leprosy (2024). Accessed 26 Oct 2024.

Towards zero leprosy. Global leprosy (Hansen’s Disease) strategy 2021–2030. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789290228509. Accessed 26 Oct 2024.

Brazil. Ministry of Health. Health Surveillance Secretariat. Department of Chronic Diseases and Sexually Transmitted Infections. Leprosy Epidemiological Bulletin. Brasília, n. Special (2023).

Minas Gerais. State Department of Health. Leprosy Confrontation Plan in Minas Gerais, 2019–2022. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 50 p. (2019).

Minas Gerais. State Department of Health. Leprosy Coordination. Epidemiological Bulletin – 2021. Vol. 1, Belo Horizonte, 50 p. (2021).

Sarno, E. N. A hanseníase no laboratório. Hist cienc saude-Manguinhos. 2003(10), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59702003000400013 (2003).

Araújo, M. G. Hanseníase no Brasil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 36(3), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822003000300010 (2003).

Brazil. Ministry of Health. Conitec recommendation protocol: Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Leprosy (2021).

Brazil. National Commission for the Incorporation of Technologies into the SUS. Recommendation Report No. 690. Qualitative molecular detection test for Mycobacterium leprae for the diagnosis of leprosy. (2021).

Reibel, F., Cambau, E. & Aubry, A. Update on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of leprosy. Med. Mal. Infect. 45(9), 383–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2015.09.002 (2015).

Souza, V. N. B. Imunologia da Hanseníase. In: Alves, Elioenai D. et al (eds.). Hanseníase: avanços e desafios. Brasília: Nesprom/Unb, p. 105–130 (2014).

Lyon, S & Grossi, M. A. F. Diagnóstico e tratamento da Hanseníase. In: Alves, Elioenai D. et al (eds.). Hanseníase: avanços e desafios. Brasília: Nesprom/Unb, p. 141–169 (2014).

Brazil. Ministry of Health. Secretariat of Health Surveillance. Department of Epidemiological Surveillance. Guide to technical procedures: bacilloscopy in leprosy. Brasília: Ministry of Health Publishing House (2010).

Castro, L. S. et al. Characterization of leishmania species from central-west region of Brazil. Parasitol Res. 117(6), 1839–1845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-018-5871-1 (2018).

Correia, J. C. et al. COHESION Project. If you will counsel properly with love, they will listen: A qualitative analysis of leprosy affected patients’ educational needs and caregiver perceptions in Nepal. PLoS ONE 14(2), e0210955. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210955 (2019).

Siwakoti, S., Rai, K., Bhattarai, N. R., Agarwal, S. & Khanal, B. Evaluation of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with slit skin smear examination (SSS) to confirm clinical diagnosis of leprosy in eastern Nepal. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10(12), e0005220. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005220 (2016).

Pinheiro MDS. Clinical, sociodemographic and laboratory profile of individuals with suspected leprosy treated at CREDEN-PES from 2017 to 2021. 75 p. Dissertation (Master’s) - Multicenter Postgraduate Program in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Governador Valadares (2022).

Goulart, I. M. & Goulart, L. R. Leprosy: Diagnostic and control challenges for a worldwide disease. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 300(6), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-008-0857-y (2008).

Maia, M. O. Molecular diagnosis of Mycobacterium leprae in the state of Mato Grosso, Central-West, Brazil. 2021. 121 p. Thesis (Doctorate) - Course of Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Postgraduate Program in Veterinary Sciences, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Cuiabá (2021).

Azevedo, M. C. et al. qPCR detection of Mycobacterium leprae in biopsies and slit skin smear of different leprosy clinical forms. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 21(1), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2016.09.017 (2017).

Turankar, R. P. et al. Comparative evaluation of PCR amplification of RLEP, 16S rRNA, rpoT and Sod A gene targets for detection of M. leprae DNA from clinical and environmental samples. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 4(1), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmyco.2014.11.062 (2015).

Ruiz-Fuentes, J. L. et al. Comparison of four DNA extraction methods for the detection of Mycobacterium leprae from Ziehl-Neelsen-stained microscopic slides. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 4(4), 284–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmyco.2015.06.005 (2015).

Huijsmans, C. J., Damen, J., van der Linden, J. C., Savelkoul, P. H. & Hermans, M. H. Comparative analysis of four methods to extract DNA from paraffin-embedded tissues: Effect on downstream molecular applications. BMC Res. Notes. 3, 239. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-3-239 (2010).

Cerda, J. & Cifuentes, L. Uso de curvas ROC en investigación clínica: Aspectos teórico-prácticos [Using ROC curves in clinical investigation: Theoretical and practical issues]. Rev. Chilena Infectol. 29(2), 138–141. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0716-10182012000200003 (2012).

Truman, R. W. et al. Enumeration of Mycobacterium leprae using real-time PCR. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2(11), e328. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000328 (2008).

Tatipally, S., Srikantam, A. & Kasetty, S. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) as a potential point of care laboratory test for leprosy diagnosis-a systematic review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 3(4), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed3040107 (2018).

State Department of Health of Minas Gerais. Updates the State Network of Laboratories in the SUS network for Direct Parasitological Diagnosis of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in the state of Minas Gerais. Belo Horizonte: SES-MG, 5 p (2015).

Barbieri, R. R. et al. Impact of a reference center on leprosy control under a decentralized public health care policy in Brazil. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10(10), e0005059. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005059 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, René Rachou Institute and Macroregional Laboratory of Teófilo Otoni for their support in carrying out this research. We would also like to thank the participants for providing their samples for the research work.

Funding

The project did not receive any funding for its implementation.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: Ana Cândida Araújo e Silva was omitted from the author list in the original version of this Article. The Author Contributions section now reads: “B.O.S.S., A.C.A.S., and D.S.T.J. wrote the main manuscript text and S.S.M. prepared figures 1-4. G.C.C. and M.A.P.X. prepared tables 1-4. All authors reviewed the manuscript.” In addition, Marcelo Antônio Pascoal Xavier was omitted as a corresponding author. Correspondence and requests for materials should also be addressed to marcelo.pascoal@fiocruz.br.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Souza e Silva, B.O., Araújo e Silva, A.C., Tolentino Júnior, D.S. et al. Accuracy of the qPCR method in intradermal scraping samples from individuals with suspected leprosy in a Brazilian macroregion. Sci Rep 15, 12537 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97714-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97714-9