Abstract

Whether an in-hospital hemoglobin drop adversely affects the prognosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains controversial. The present study aimed to investigate the impacts of in-hospital hemoglobin drop without overt bleeding on 1-year clinical outcomes of AMI patients after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). A total of 5,036 AMI patients who underwent PCI and presented with an in-hospital hemoglobin decline without overt bleeding were recruited in this study. Subsequently, these patients were stratified into three cohorts based on tertiles of hemoglobin drop values: < 0.8 g/dL (n = 1652), 0.8–1.49 g/dL (n = 1651) and ≥ 1.5 g/dL (n = 1733). The primary endpoint was defined as ischemic events at 1 year, composed of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke. Secondary endpoints were defined as 1-year all-cause death, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) types 2, 3, or 5, and 3 or 5 bleeding. There were significant differences in 1-year incidence of ischemic events (1.88% vs. 3.27% vs. 3.46%; P = 0.0114), all-cause death (1.45% vs. 2.18% vs. 2.94%; P = 0.0128), as well as cardiac death (1.15% vs. 1.82% vs. 2.37%; P = 0.0282) and MI (0.30% vs. 1.15% vs. 0.92%; P = 0.0175) across tertiles of hemoglobin drop values. For each 1 g/dL drop in hemoglobin values, the adjusted risk for ischemic events and all-cause death increased by 2% and 3%, respectively. Among AMI patients undergoing PCI, an in-hospital decline in hemoglobin levels was associated with an increased risk of 1-year ischemic events and all-cause death, even in the absence of overt bleeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The extensive application of standardized anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy has significantly improved the clinical prognosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), albeit with an increased risk of bleeding.1,2,3 Periprocedural bleeding, a common complication in AMI patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), has been found to be significantly associated with poor prognosis, including increased mortality.3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10

At present, a hemoglobin drop threshold of 3 to 5 g/dL is mostly used to grade the severity of bleeding. Specifically, a hemoglobin drop of 5 g/dL without overt bleeding, or a drop of 3 g/dL with overt bleeding, is commonly defined as major bleeding and used as endpoint events in most clinical trials and registries.5,11,12,13 Nevertheless, the incidence of major bleeding events was relatively low in the clinical practice, with most patients suffering from a hemoglobin decline in the absence of overt bleeding.14,15 The data regarding the association between in-hospital hemoglobin drop without overt bleeding and clinical outcomes in AMI patients remain limited.

In this retrospective study, we aimed to investigate the impacts of in-hospital hemoglobin drop without overt bleeding on 1-year clinical outcomes of AMI patients after PCI.

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics

A total of 5036 AMI enrolled in final analysis with a 99.3% follow-up rate at 1 year. The flowchart is presented in Supplemental Fig. 1. The demographic and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The level of hemoglobin at admission and nadir during hospitalization are shown in Supplementary Materials Table S1. Baseline characteristics varied considerably among the three groups. In general, with incremental hemoglobin drop stratification, patients were more likely to present with STEMI, as well as lower eGFR (91.51 ± 24.00 vs. 88.73 ± 24.10 vs. 83.54 ± 25.44 ml/min/1.73 m2, P < 0.0001) and lower LVEF values (55.29 ± 8.73 vs. 55.21 ± 8.88 vs. 53.48 ± 9.39%, P < 0.0001). Besides, lower proportion of PCI performed with trans-radial access, and an increase in the proportion of right coronary artery as a target lesion were found in patients with incremental hemoglobin drop (Table 2). Regarding discharge medications, the use of aspirin, statin and ACEI/ARB decreased with the degree of hemoglobin drop increased (Table 3).

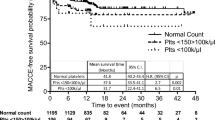

Stratified clinical outcomes

1-year Clinical outcomes of patients stratified by the degree of hemoglobin drop are reported in Table 4. There were significant differences in 1-year incidence of ischemic events (1.88% vs. 3.27% vs. 3.46%; P = 0.0114), all-cause death (1.45% vs. 2.18% vs. 2.94%; P = 0.0128), as well as cardiac death (1.15% vs. 1.82% vs. 2.37%; P = 0.0282) and MI (0.30% vs. 1.15% vs. 0.92%; P = 0.0175) across tertiles of hemoglobin drop values. However, no significant differences were observed in bleeding events. Time-to-event curves are shown in Fig. 1.

Considering hemoglobin drop as a continuous variable, the adjusted risk of 1-year ischemic events was increased by 2% for each 1 g/dL hemoglobin drop (HR: 1.02, 95%CI 1.001–1.04, P = 0.01). An independent association between in-hospital hemoglobin drop and 1-year all-cause death was found in AMI patients and showed that for each 1 g/dL hemoglobin drop, the adjusted risk for 1-year all-cause death was increased by 3% (HR: 1.03, 95%CI 1.01–1.04, P = 0.008) (Table 5).

The diagnostic ability of the in-hospital hemoglobin drop to discriminate patients with respect to 1-year ischemic events and all-cause death was assessed by ROC curve analysis. Applied for the whole group of patients, the AUC for 1-year ischemic events and all-cause death was 0.58 (95% CI 0.53–0.62) and 0.60 (95% CI 0.55–0.65), respectively (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The results of the study, which was conducted over a cohort of AMI patients undergoing PCI, indicated that an decline in hemoglobin during hospitalization was associated with an increased risk of 1-year ischemic events and all-cause death, even in the absence of overt bleeding. Besides, for each 1 g/dL hemoglobin drop, the adjusted risk of 1-year ischemic events was 2% higher in AMI patients, as well as 3% higher adjusted risk for all-cause death.

Patients diagnosed with AMI may present with decreased hemoglobin during hospitalization due to the application of invasive treatment and antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, both of which can cause hemorrhage.3,14,15,16,17,18 Numerous clinical investigations have provided substantial evidence for the association between major bleeding events and adverse outcomes after PCI.6,7,8,9,10,19 However, major bleeding events were not commonly observed in the clinical practice.14,15 Hence, the attention paid to non-major bleeding has been relatively limited, resulting in the neglect of adverse outcomes caused by potential bleeding events. Nevertheless, evidence supporting the association between hemoglobin decrease without overt bleeding and clinical outcomes is insufficient.

In our analysis, there was a significant association between the decline in hemoglobin, without overt bleeding during hospitalization and an increased risk of 1-year ischemic events and all-cause death. Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies. Among ACS patients with PCI, in-hospital hemoglobin drop ≥ 3 g/dL has been found to be independently associated with increased risk for 1-year mortality in the absence of overt bleeding.14 Moreover, Ndrepepa et al. demonstrated that the association between hemoglobin decline and 1-year mortality remained significant when patients with obvious in-hospital bleeding were excluded, and the minimal decline in hemoglobin levels associated with mortality was 1.13 g/dL in patients without overt bleeding.15 Besides, a decline in hemoglobin ≥ 0.9 g/dL in patients with ACS during intensive care unit (ICU) stay was found to be associated with adverse clinical outcomes within 6 months, which provided additional prognostic information on top of the GRACE score.20 Another study focused on non-overt bleeding ICU-admitted patients with AMI revealed that in-hospital hemoglobin drop was independently associated with higher 180-day all-cause mortality.21 Hence, the above studies support the association between in-hospital hemoglobin drop and clinical events to some extent.

The mechanism of in-hospital hemoglobin drop is probably complex and influenced by multiple factors. Previous studies suggested that therapeutic fluid use,22 suppression of erythropoiesis due to cytokines generated as a response to myocardial necrosis,23 and baseline anemia24 might be possible causes of in-hospital hemoglobin drop without overt bleeding. Therefore, adverse cardiovascular risk profile related to in-hospital hemoglobin decline, and the exacerbation of myocardial ischemia induced by anemia, may account for the poor prognosis in these patients. Honestly, prior studies14,15,21 have indicated a potential correlation between hemoglobin decline and subsequent clinical outcomes in ACS patients who do not present with overt bleeding. However, the current study has made significant improvements in two aspects. Firstly, it focuses on the specific STEMI patient with appropriate sample size, which could support to eliminate potential confounding from different subtypes of ACS and prevent insufficient statistical power. Second, unlike most prior studies, it is of utmost importance to provide evidence from the East Asian population.

Limitation

There are several limitations that should be considered in this study. Firstly, patients without baseline (on admission) or nadir (lowest hemoglobin value measured during hospitalization) inpatient hemoglobin values were excluded, which may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. Secondly, the possible reasons for the hemoglobin drop in AMI patients were not analyzed, as hematological disorders, malignant tumors or other anemia-related diseases conditions could also cause a drop in hemoglobin levels, and these factors may potentially influence the prognosis of the patients. Consequently, the disregard of these potential confounding factors may limit the validity of the results. Further studies with larger sample sizes, prospective designs, and comprehensive analyses of potential confounding factors are needed for a better understanding of our findings.

Conclusion

In AMI patients who have undergone PCI, an in-hospital decline in hemoglobin levels is associated with an increased risk of 1-year ischemic events and all-cause death, even in the absence of overt bleeding. This finding provides important evidence for the clinical management and prognostic assessment of AMI patients, suggesting that clinicians should closely monitor the changes in patients’ hemoglobin levels during the treatment process to enable timely intervention measures and improve prognoses.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed patients who underwent PCI at the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command from March 2016 to March 2019. A standard web-based data collection system (CVNET, Crealife Technology) was used to collect patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, sex, medical history, PCI indication, laboratory findings, angiographic and procedural characteristics, and medication treatment. These patients had both baseline (on admission) and nadir (lowest hemoglobin value measured during hospitalization) inpatient hemoglobin values. Of 5,036 included patients reported an in-hospital hemoglobin drop without overt bleeding. These patients were divided into 3 groups based on tertiles of the degree of hemoglobin drop: hemoglobin drop < 0.8 g/dL (n = 1652), 0.8–1.49 g/dL hemoglobin drop (n = 1651) and ≥ 1.5 g/dL hemoglobin drop (n = 1733). Follow-up information was obtained by telephone at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year after the discharged by staff members who were unaware of the clinical process. This study was approved by the institutional ethical committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command [No. Y(2023)198] with a waiver of the requirement to obtain informed consent to conduct this analysis. And the study complied with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Definition

The definition of hemoglobin drop was baseline hemoglobin (at admission) minus nadir (lowest hemoglobin value measured during hospitalization). Besides, a standardized definitions of endpoints was used in the present study.25

The primary outcome was ischemic events at 1 year, defined as a composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke. Secondary endpoints were defined as 1-year all-cause death, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) types 2, 3, or 5, and 3 or 5 bleeding.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using analysis of variance. Categorical variables are presented as number (percentage) and were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Time-to-event outcomes were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method, and compared by the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazard regressions were performed to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) and evaluate the associations between hemoglobin drop and clinical outcomes. Variables selected for adjusted in multivariable model were patient characteristics including age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, a history of MI, previous stroke, previous PCI, smoking status, types of AMI, estimated glomerular filtration rate, procedure information (transradial access, coronary arteries treated), and medical treatment (aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitors, statin, ACEI/ARB, β-blockers). Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) for hemoglobin drop was constructed to assess the predictive accuracy for 1-year ischemic events with the area under the curve (AUC). Unless otherwise specified, a 2-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The statistical analysis was conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

Roffi, M. et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 37, 267–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320 (2016).

Levine, G. et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: An update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 1235–1250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.005 (2016).

Buccheri, S., Capodanno, D., James, S. & Angiolillo, D. Bleeding after antiplatelet therapy for the treatment of acute coronary syndromes: A review of the evidence and evolving paradigms. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 18, 1171–1189. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2019.1680637 (2019).

Rao, S. et al. Bleeding and blood transfusion issues in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 28, 1193–1204. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehm019 (2007).

Valgimigli, M. et al. Trade-off of myocardial infarction vs. bleeding types on mortality after acute coronary syndrome: Lessons from the thrombin receptor antagonist for clinical event reduction in acute coronary syndrome (TRACER) randomized trial. Eur. Heart J. 38, 804–810. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw525 (2017).

Vranckx, P. et al. Validation of BARC bleeding criteria in patients with acute coronary syndromes: The TRACER trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 2135–2144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.056 (2016).

Mehran, R. et al. Associations of major bleeding and myocardial infarction with the incidence and timing of mortality in patients presenting with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a risk model from the ACUITY trial. Eur. Heart J. 30, 1457–1466. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp110 (2009).

Kinnaird, T. et al. Incidence, predictors, and prognostic implications of bleeding and blood transfusion following percutaneous coronary interventions. Am. J. Cardiol. 92, 930–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00972-x (2003).

Kuno, T. et al. Association of decreasing hemoglobin levels with the incidence of acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention: A prospective multi-center study. Heart Vessels 36, 330–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-020-01706-w (2021).

Ohno, Y. et al. Impact of periprocedural bleeding on incidence of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, 1260–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.086 (2013).

Mehran, R. et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: A consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation 123, 2736–2747. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.110.009449 (2011).

Bovill, E. G. Hemorrhagic events during therapy with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator, heparin, and aspirin for acute myocardial infarction. Results of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI), Phase II Trial. Ann. Internal Med. 115, 256–265 (1991).

Steinhubl, S. R., Kastrati, A. & Berger, P. B. Variation in the definitions of bleeding in clinical trials of patients with acute coronary syndromes and undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions and its impact on the apparent safety of antithrombotic drugs. Am. Heart J. 154, 3–11 (2007).

Leonardi, S. et al. prognostic implications of declining hemoglobin content in patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77, 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.046 (2021).

Ndrepepa, G. et al. Prognostic value of haemoglobin drop in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 51, e13670. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13670 (2021).

Farhan, S., Baber, U. & Mehran, R. Anemia and acute coronary syndrome: time for intervention studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.116.004908 (2016).

Mahendiran, T. et al. Prognosis of patients with chronic and hospital-acquired anaemia after acute coronary syndromes. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 13, 618–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12265-019-09934-w (2020).

Velásquez-Rodríguez, J. et al. Prognostic impact of age and hemoglobin in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with reperfusion therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 119, 1909–1916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.03.018 (2017).

Dutsch, A. et al. Association of in-hospital hemoglobin drop with decreased myocardial salvage and increased long-term mortality in patients with acute ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e024857. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.121.024857 (2022).

Maréchaux, S. et al. Prognostic value of hemoglobin decline over the GRACE score in patients hospitalized for an acute coronary syndrome. Heart Vessels 27, 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-011-0127-3 (2012).

Li, P. et al. Prognostic impact of in-hospital hemoglobin decline in non-overt bleeding ICU patients with acute myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03251-6 (2023).

Haught, W. H. et al. Decrease in hematocrit after coronary stent placement and dextran therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 76, 314–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80091-5 (1995).

Aronson, D. et al. Changes in haemoglobin levels during hospital course and long-term outcome after acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 28, 1289–1296. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehm013 (2007).

Bertrand, O. F. et al. Incidence, range, and clinical effect of hemoglobin changes within 24 hours after transradial coronary stenting. Am. J. Cardiol. 106, 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.03.013 (2010).

Garcia-Garcia, H. M. et al. standardized end point definitions for coronary intervention trials: The academic research consortium-2 consensus document. Eur. Heart J. 39, 2192–2207. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy223 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2503500 and 2022YFC2503504).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z. was responsible for writing the original draft, data curation, and conceptualization. M.Q. was responsible for methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and visualization. S.G., Z.L., and Y.L. were responsible for the investigation, data curation, and project administration. Y.H. was responsible for conceptualization, funding acquisition, data curation, project administration, and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional ethical committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command [No. Y(2023)198] with a waiver of the requirement to obtain informed consent to conduct this analysis. And the study complied with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, H., Qiu, M., Guan, S. et al. Association between in-hospital hemoglobin drop without overt bleeding and 1-year outcome of percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction patients. Sci Rep 15, 12773 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97762-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97762-1