Abstract

The connection between fluoroquinolones and severe heart conditions, such as aortic aneurysm (AA) and aortic dissection (AD), has been acknowledged, but the full extent of long-term risks remains uncertain. Addressing this knowledge deficit, a retrospective cohort study was conducted in Taiwan, utilizing data from the National Health Insurance Research Database spanning from 2004 to 2010, with follow-up lasting until 2019. The study included 232,552 people who took fluoroquinolones and the same number of people who didn’t, matched for age, sex, and index year. The Cox regression model was enlisted to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) for AA/AD onset. Additionally, five machine learning algorithms assisted in pinpointing critical determinants for AA/AD among those with fluoroquinolones. Intriguingly, within the longest follow-up duration of 16 years, exposed patients presented with a markedly higher incidence of AA/AD unexposed patients (80 vs. 30 per 100,000 person-years). After adjusting for multiple factors, exposure to fluoroquinolones was linked to a higher risk of AA/AD (HR 1.62, 95%CI 1.45–1.78). Machine learning identified ten factors that significantly affected AA/AD risk in those exposed. The findings illustrate a 62% elevation in the long-term risk of adverse outcomes associated with AA/AD following the administration of fluoroquinolones and concurrently delineate the salient factors contributing to AA/AD, underscoring the imperative for healthcare practitioners to meticulously evaluate the implications of prescribing these antibiotics in light of the associated risks and determinants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fluoroquinolone, a class of broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs effective against a variety of gram-negative and gram-positive pathogens, have been widely used for several decades1.

Despite their efficacy in treating a range of infections, these agents have been associated with several safety concerns, including tendinopathy, QTc prolongation, and, potentially, adverse effects on collagen and other connective tissue structures2,3,4,5. In recent years, concerns have extended to the potential long-term risk of serious vascular complications, particularly aortic aneurysm (AA) and aortic dissection (AD), the latter being catastrophic events associated with high mortality rates6,7.

Aortic aneurysm, a condition characterized by an abnormal focal dilation of the arterial wall, and its extreme sequel, dissection, pose significant health burdens due to their asymptomatic nature and potential for sudden, fatal rupture8,9. Emerging epidemiological evidence suggests that fluoroquinolones may contribute to these disorders by disrupting the integrity of collagen within the aortic wall, thus underlining a pressing need for a comprehensive review of their long-term vascular risks10,11,12. The concern was first raised when laboratory studies highlighted the capacity of fluoroquinolones to upregulate matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), enzymes responsible for the degradation of collagen and elastin, which play a crucial role in maintaining the structural integrity of the aorta13,14. Increasing the levels and activity of MMPs, including MMP-9, while reducing the expression of lysyl oxidase, leads to elastic fiber fragmentation and aortic cell injury15.

In 2008, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning for fluoroquinolones based on post-marketing surveillance data indicating their association with post-treatment tendonitis and tendon rupture. Subsequent studies demonstrated the association of fluoroquinolones with increased risk of AA and AD16,17. In population-based cohort studies in Canada and Sweden, Daneman et al.18 and Pasternak et al.11 found that fluoroquinolones exposure was associated with greater risk of AA (hazard ratio [HR] 2.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.02–2.49) and AA/AD (HR 1.66, 95%CI 1.12–2.46), respectively. These findings are supported by several case-control studies NHIRD10,12,19,20,21.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has recently become increasingly popular. Machine learning, a branch of AI that mimics human intelligence by incorporating and analyzing data, is widely used in researching fields22,23. AI improves clinical decision-making by offering faster and more accurate results. It detects conditions, supports decisions, and evaluates treatments, enhancing healthcare delivery24,25,26. In diagnostics, AI analyzes medical images for quick diagnoses27. Machine learning predicts diseases and assesses records, improving outcomes28,29. By using diverse datasets, AI generates insights from health records and biomedical data, boosting patient care30,31,32.

Although previous studies have identified a potential association between AA/AD and fluoroquinolone exposure, there may be limitations regarding the long-term follow-up of patients taking fluoroquinolones. Our study embarked on a comprehensive exploration of the potential link between fluoroquinolone exposure and the development of aortic aneurysm (AA) and aortic dissection (AD) over an extended timeline. Utilizing the extensive data available from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), our objective was to thoroughly assess the connection between fluoroquinolone use and the risk of AA/AD in a real-world context. Moreover, we aimed to identify predictive markers that could be leveraged in clinical settings to assess the risk of AA/AD in patients prescribed fluoroquinolones. To accomplish this, we employed advanced machine learning techniques to analyze the data, aiming to provide clinically relevant insights that could inform safer prescribing practices and enhance patient care.

Materials and methods

Data sources

Our study was designed as a retrospective cohort, utilizing the extensive information available from the NHIRD. The NHIRD, since its establishment in 1998, has been an exhaustive resource, encompassing coverage for a sweeping majority of the population in Taiwan, accounting for nearly 99%33. This expansive database holds a wealth of data points covering different aspects of healthcare services such as hospital stays, appointments with medical professionals in outpatient settings, along with a plethora of other healthcare-related information. It encompasses detailed records of surgical procedures undergone by individuals, the variety of medications prescribed, and the specific disease diagnosis codes assigned to patients’ conditions. These diagnostic codes are formulated in alignment with the globally recognized International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision Clinical Modification, commonly abbreviated as International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision Clinical Modification34. Before releasing the data analysis, Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) took important measures to protect the privacy of people represented in our study. The MOHW carefully anonymized the records of all claimants, stripping the dataset of any personal identifiers effectively.

In preparation for our in-depth analysis, we ensured that all personal identifiers within the beneficiary claim records had been removed, rendering the data deidentified for the protection of personal privacy. The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shin-Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital (protocol No.: 20200720R). The board also authorized a waiver of informed consent for this study, allowing us to proceed without requiring direct consent from the individuals included in the dataset. All methods were performed in strict accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population and baseline variables

This was a retrospective population-based cohort study. The database we used for our study included information from 2002 to 2019. Our attention was directed towards individuals who were registered between the dates of January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2010. Subsequently, we diligently observed their progress until the conclusion of the observation period on December 31, 2019.

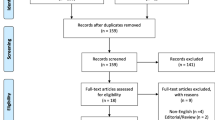

Figure 1 illustrates the scheme for selecting patients in our study from 2004 to 2010. We had a group of patients who were exposed to fluoroquinolones. This group consisted of 232,552 individuals who were prescribed either oral fluoroquinolones (specifically ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and gemifloxacin) or intravenous fluoroquinolones (specifically ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin) during a visit to the outpatient department or as part of a hospital admission. To identify patients with new onset conditions, we applied the following exclusion criteria: (1) patients who had received fluoroquinolones prescriptions prior to 2002–2003, (2) patients who had already been diagnosed with AA or AD in 2002–2003, (3) patients with missing information, and (4) patients under the age of 18. The index date of the group with fluoroquinolones exposure was one month after the initial medication of fluoroquinolones records.

To form a comparison group that hadn’t been exposed to fluoroquinolones, we systematically paired individuals with counterparts from the group of those who did receive fluoroquinolones, ensuring that each match was made with a 1:1 ratio. This meticulous pairing process considered several important characteristics. Age, gender, and the specific year within the range of 2004 to 2010, also known as the index year, were the key factors considered to align the two groups as closely as possible. For the group that had not been exposed to fluoroquinolones, we assigned an index date that corresponded directly to the index date for their paired counterparts who had been exposed to the medication. This method allowed for consistent comparison across both groups while simultaneously achieving an equitable duration for follow-up assessments.

Definition of variables

Three variable categories were included in the present study. The first category included those included in propensity score matching (index years, age, sex). The second category was composed of comorbidities including hypertension; hyperlipidemia; diabetes mellitus (DM); cirrhosis; chronic kidney disease; cerebrovascular disease; ischemic stroke; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); coronary artery disease (CAD); asthma; genital tract infection (GTI), soft tissue and bone infection (STBI), and lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI); septicemia; and seizure disorder (Supplementary Table S1 for codes of diseases). The third category was composed of medications including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers (CCB), insulin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), diuretics, and oral and intravenous steroids (Supplementary Table S2 online for codes of medications).

Study outcomes

The main result of our study focused on patients who were admitted to the hospital for AA/AD, for which the specific codes used to identify these conditions are provided in further detail in Supplementary Table S1. The dataset was examined, starting from the index date, and continued until the specific endpoints were reached. This close examination was carried out up to the point at which the first instance of a new AA/AD diagnosis was identified, the occurrence of death from any cause, or until the preset conclusion of the observation period, which was determined to be December 31, 2019. The analysis concluded with whichever of these three events happened the earliest.

Statistical analysis

We presented all demographic results as percentages for categorical data and as means with standard deviations for continuous data. Categorical and continuous variables were compared using the chi-square and Student’s t tests, respectively.

To further mitigate confounding variables, we utilized propensity score matching (1:1 ratio) prior to the implementation of the Cox regression model. We conducted the Cox regression analysis in two distinct phases. Initially, we performed a crude analysis to ascertain the unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) for AA/AD associated with exposure to fluoroquinolones. Subsequently, we executed an adjusted analysis to incorporate potential confounding variables, thereby further diminishing residual confounding, which included a thorough array of baseline characteristics such as age, sex, comorbidities, and prior medication usage. We tested the proportional hazard assumption by schoenfeld residuals. A two-tail P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

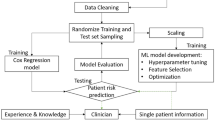

Moreover, feature selection was used to find the important features of AA/AD in patients with fluoroquinolones exposure, thereby excluding unimportant variables and improving the accuracy of machine learning models35,36. Feature selection is a significant challenge in most classification problems. In certain biomedical fields, it goes beyond merely enhancing the computational efficiency of machine learning algorithms; it is crucial for knowledge discovery37,38,39. Feature selection models used in the present study were logistic regression (LGR)40, random forest (RF)41, classification and regression tree (CART)42, multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS)43, and extreme gradient boosting (eXGBoost)44. The R packages for various machine learning algorithms are as follows: “glm” for LGR, “randomForest” for RF, “caret” for CART, “earth” for MARS, and “xgboost” for XGBoost. For Random Forest, important parameter settings include the number of trees to grow (ntree = 700) and the minimum size of terminal nodes (nodesize; set to 1 for classification). For CART, parameters include minsplit, which is the minimum number of observations required in a node to consider a split (set to 20), and the complexity parameter (cp. = 0.05). For XGBoost, key parameters include the learning rate (learning_rate = 0.5) and the maximum depth of a tree (max_depth = 10) (Supplementary Method for machine learning). Since the algorithm used for each model was different, the selection process for each variable varied as well. To ensure fairness, this research averaged all the features generated by each model and ranked the scores from high to low. The variable with the highest average score was considered the most important, and so on (Supplementary Figure S1 online for the flow chart of feature selection). The R software (version 3.4.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for feature selection (Supplementary Table S3: Code for machine learning methods).

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

The distributions of age, sex, comorbidities, and medications of target population are presented in Table 1. Briefly, the rates of comorbidities were significantly higher in the group with fluoroquinolones exposure than in those without fluoroquinolones exposure and included hypertension (13.22% vs. 7.84%, P < .001), hyperlipidemia (30.95% vs. 24.02%, P < .001), DM (33.21% vs. 19.67%, P < .001), cirrhosis (5.37% vs. 1.83%, P < .001), chronic kidney disease (16.18% vs. 4.84%, P < .001), stroke (26.02% vs. 12.48%, P < .001), ischemic stroke (8.89% vs. 2.87%, P < .001), COPD (42.87% vs. 22.03%, P < .001), CAD (11.88% vs. 3.84%, P < .001), asthma (23.92% vs. 11.83%, P < .001), GTI (60.98% vs. 31.56%, P < .001), STBI (50.26% vs. 30.56%, P < .001), LRTI (49.59% vs. 21.79%, P < .001), septicemia (10.77% vs. 3.73%, P < .001), and seizure disorder (0.83% vs. 0.21%, P < .001). Similarly, the use rates of specific medications were significantly higher in the group with fluoroquinolones exposure than in those without fluoroquinolones exposure and included ACEI/ARB (12.11% vs. 7.82%, P < .001), beta-blockers (14.83% vs. 11.18%, P < .001), CCB (26.18% vs. 15.7%, P < .001), insulin (11.13% vs. 1.08%, P < .001), NSAID (46.81% vs. 31.64%, P < .001), diuretics (2.62% vs. 2.02%, P < .001), oral steroids (65.66% vs. 45.08%, P < .001), and intravenous steroids (54.29% vs. 23.62%, P < .001).

Risk factors for the development of AA/AD

Table 2 shows the determinants of AA/AD in the study population. In multivariable analysis, in addition to fluoroquinolones (HR 1.62, 95%CI 1.45–1.78), old age (HR 2.21, 95%CI 1.55–3.14 for 40–55 years vs. <40 years; HR 9.39, 95%CI 6.83–12.92 for ≥ 55 years vs. <40 years), male sex (HR 2.47, 95%CI 2.23–2.74), hypertension (HR 1.14, 95%CI 1.02–1.28), DM (HR 0.75; 95%CI 0.68–0.83), cirrhosis (HR 0.75, 95%CI 0.57–0.97), cerebrovascular disease (HR 1.30, 95%CI 1.16–1.45), CAD (HR 1.50, 95 CI 1.16–1.93), asthma (HR 0.88, 95%CI 0.79–0.97), septicemia (HR 1.36, 95%CI 1.20–1.54), ACEI/ARB (HR 1.40, 95%CI 1.24–1.58), beta-blockers (HR 1.36, 95%CI 1.22–1.51), CCB (HR 1.59, 95%CI 1.44–1.75), insulin (HR 0.56, 95%CI 0.45–0.70), NSAIDs (HR 0.90, 95%CI 0.82–0.98), oral steroids (HR 1.75, 95%CI 1.56–1.96), and intravenous steroids (HR 4.29, 95%CI 3.82–4.81) were independently associated with the development of AA/AD.

Association of fluoroquinolones exposure with AA/AD

Over a longest 16-year follow-up period, the Kaplan-Meier plot in Fig. 2 reveals a significant difference in the occurrence of AA/AD events between groups exposed to fluoroquinolones and those not exposed (p < .001). Additionally, Table 3 illustrates that we compared 1,389 patients who recently developed AA or AD and were exposed to fluoroquinolones to 675 patients who also recently developed AA or AD but were not exposed to fluoroquinolones. The incidence of AA/AD was higher in the group exposed to fluoroquinolones compared to those not exposed (80 vs. 30 per 100,000 person-years).

The initial analysis showed a clear link between taking fluoroquinolones and a higher chance of developing AA/AD (HR 2.39, with a 95% CI of 2.18–2.62; the p < .001). Even after considering all the factors listed in Table 1, the use of fluoroquinolones was still significantly linked to an increased risk of getting AA/AD for the first time (the adjusted HR is 1.62, with a 95% CI of 1.47–1.78; p < .001).

Subgroup analysis

We further performed subgroup analysis to determine the effect of the baseline variables on AA/AD risk (Fig. 3). Almost all patients had increased HRs of entering AA/AD indicators in the favor of fluoroquinolones non-exposure, the risk for AA/AD was higher in patients younger than 40 years (HR 3.94, 95%CI 1.82–8.55). In addition, the risk for AA/AD was not different between the patients with and without fluoroquinolones exposure among those using intravenous steroids.

The subgroup analysis of the effect of fluoroquinolone exposure on the aortic aneurysm or aortic dissection. FQs Fluoroquinolone, CKD chronic kidney disease, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, STBI soft tissue and bone infection, LRTI lower respiratory tract infection, GTI genital tract infection.

Critical factors to develop AA/AD in patients exposed to fluoroquinolones

Figure 4 shows how variables rank according to their average importance scores, as determined by the machine learning methods of LGR, RF, MARS, CART, and eXGBoos. The top ten most significant variables, listed from the most to the least important, are intravenous steroid, insulin, CCB, DM, oral steroid, beta-blockers, ACEI/ARB, hyperlipidemia, COPD, and patient’s age (Supplementary Table S4 for the importance scores).

Ranking of parameters important factors for aortic dissection and aneurysm in patients with fluoroquinolones exposure based on machine learning methods. IV, intravenous; ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB angiotensin receptor blocker, CCB calcium channel blocker, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study examining the impact of fluoroquinolones exposure on AA/AD incidence, our analyses revealed a 1.6-fold increased long-term risk of AA/AD among patients exposed to fluoroquinolones, with a significant association noted across nearly all subgroups that were analyzed. Using machine learning methods, we identified ten crucial factors contributing to AA/AD development in patients exposed to fluoroquinolones. These empirical findings endeavor to assist healthcare practitioners in the formulation of methodologies for the surveillance and prevention of AA/AD among patients undergoing treatment with fluoroquinolones, thereby mitigating associated health hazards. Medical practitioners must meticulously assess the potential hazards associated with the administration of fluoroquinolones, particularly in patients who exhibit specific demographic and clinical profiles, such as elderly individuals, those without diabetes mellitus, patients with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and COPD, or those undergoing corticosteroid therapy. The pursuit of safer antibiotic alternatives should be prioritized whenever it is practicable to do so. In situations where the use of fluoroquinolones is deemed indispensable, healthcare providers are required to diligently monitor for any possible vascular complications and to furnish patients with extensive information regarding the associated risks.

The absolute risk difference (ARD) provides an essential perspective to contextualize the impact of fluoroquinolone exposure on the risk of AA/AD45. In our study, we observed that the incidence rate of AA/AD amounted to a striking 80 cases for every 100,000 person-years among those patients who were exposed to fluoroquinolones, in stark contrast to the significantly lower incidence rate of 30 cases per 100,000 person-years documented in the cohort of patients who did not undergo such exposure, thereby culminating in a calculated ARD of 50 cases per 100,000 person-years. This finding emphatically underscores the notion that the utilization of fluoroquinolones is associated with an incremental increase of 50 additional cases of AA/AD for every 100,000 individuals on an annual basis, which is a significant public health concern. Moreover, while the observed relative risk escalation of 62% (with a HR of 1.62) highlights a robust and substantial correlation between fluoroquinolone exposure and the risk of AA/AD, the quantification of the ARD serves to render our research findings not only more tangible but also profoundly clinically relevant, thereby enhancing their applicability in clinical settings.

The mechanism underlying fluoroquinolones-induced AA/AD is not fully understood, although two hypotheses have been proposed. The first hypothesis posits that fluoroquinolones interfere with the integrity of the extracellular matrix, resulting in homeostatic dysregulation and impaired biomechanical strength in aorta, and ultimately triggering progressive aortic weakening, dissection, and rupture by upregulating the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and reducing the levels of tissue inhibitors of MMPs46,47. Increased MMP expression has been reported in smooth muscle cells in patients with abdominal AA48 and in cornea and tendons in animals exposed to fluoroquinolones14,49. The second hypothesis proposes that fluoroquinolones, which are DNA topoisomerase inhibitors, promote mitochondrial dysfunction, suppress cell proliferation, and induce apoptosis15,50, ultimately leading to aortic damage.

In addition to fluoroquinolones, the well-known risk factors of AA/AD include older age, male sex, lifestyle habits such as cigarette smoking and stimulant abuse, and clinical conditions such as COPD, prolonged arterial hypertension, obesity, atherosclerosis, chronic kidney disease, trauma, vasculitis, bacterial infection, and congenital connective tissue disorders51,52,53. AA/AD results from weakened aortic integrity, caused by either genetic issues like connective tissue disorders or conditions like age-related atherosclerosis. While extracellular matrix degradation and inflammation contribute to this aortic degeneration, the exact cause of dissection is unknown. Once the aortic wall is compromised, ongoing dissections are worsened by the mechanical stress of blood flow54. The association between previously reported risk factors and AA/AD were listed in Table 2.

Further, we found that certain antihypertensive medications (ACEI/ARB, CCB, and beta-blockers) were associated with increased AA/AD risk in Cox regression model. This finding contradicts previous studies linking the renin-angiotensin system to AA and suggesting that antihypertensive medications are beneficial for patient outcomes after the development of AA/AD55,56. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that hypertension is a known risk factor for AA/AD57 and that individuals with hypertension are often prescribed these antihypertensive medications. Therefore, in the present study, the association of antihypertensive medications with increased AA/AD risk might reflect the presence of high blood pressure, a known AA/AD risk factor, in these patients.

Based on our machine learning analysis, the top ten important factors for the development of AA/AD in patients with fluoroquinolones exposure were age, comorbidities such as DM, hyperlipidemia, and COPD, and medications including intravenous steroids, insulin, CCB, beta-blockers, and ACEI/ARB. Of these, intravenous steroid use was the top-scoring predictor of AA/AD. Of note, antihypertensive medication use might reflect preexisting high blood pressure. As indicated in Table 2, which outlines the risk determinants for AA/AD, and Fig. 4, which ranks the important risk factors, most of the top ten significant factors for AA/AD are also related to an increased risk of AA/AD. The only exceptions are diabetes mellitus (DM) and insulin use, which may play a role in reducing the risk of AA/AD in patients exposed to fluoroquinolones. Overall, the results mentioned above offer important insights for tracking patients exposed to fluoroquinolones.

Glucocorticoids are often used in combination with fluoroquinolones for inpatients. However, a case series reported that treatment with anabolic steroids increased the risk of AD in athletes, particularly in association with exercise58. Furthermore, Sendzik et al. reported that the combined use of steroids and fluoroquinolones increased the levels of MMPs and activated caspase 3, indicating apoptosis, in tenocyte cultures59. These results are consistent with the present study finding that steroid use, either intravenous or oral, might be associated with the development of AA/AD.

DM is a well-established risk factor for coronary and cerebrovascular diseases. However, the DM prevalence is surprisingly lower in individuals with abdominal AA than in those without abdominal AA (6–14% vs. 17–36%)60. In fact, a 3-year follow-up study found that DM was independently associated with reduced abdominal AA growth61. Similarly, Prakash et al. reported an inverse association between DM and the rate of hospitalization for thoracic AD62. In a meta-analysis including 14 studies and 15 794 patients, Li et al. found that the DM prevalence was lower in patients with AD than in those without AD (odds ratio 0.51, 95%CI 0.33–0.81)63. However, the mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of hyperglycemia in thoracic AD is not fully understood. In the present study, insulin had a beneficial effect and prevented the development of AA/AD. Insulin use may play an important role in the negative association observed between DM and the development of AA/AD.

Recent studies have increasingly shown the role of inflammation and macrophage infiltration in the development of AD64,65. In a murine model, Tomida et al. found that the use of indomethacin, an NSAID, prevented death due to abdominal AD and reduced the incidence of AD by up to 40%66. This effect might be attributed to the inhibition of monocyte transendothelial migration and blockade of the accumulation of monocytes/macrophages in the aortic wall. IL-6 plays a key role in inflammation leading to AA. High IL-6 levels cause macrophages to gather and release MMPs, breaking down the aortic wall and causing aneurysms to form and grow67. This is compatible with our findings, indicating the potential use of NSAIDs to prevent the development of AD.

Feature selection is crucial in machine learning, especially in biomedical fields, to identify important features and improve model performance35,36. This involves creating feature subsets, selecting the best one, iterating until a stopping criterion is met, and validating the optimal subset. The discussed models—LGR, CART, RF, MARS, and XGBoost—have unique traits. LGR is simple but assumes linear relationships. CART is intuitive but overfits easily. RF is robust with feature importance but is computationally intense. MARS handles high-dimensional, nonlinear data but can overfit. XGBoost offers high performance with regularization but needs careful tuning and resources (Supplementary Method, the parameters in ML). Combining these models leverages their strengths and improves understanding of feature importance and predictive performance. Machine learning methodologies augment Cox regression by elucidating intricate, non-linear correlations and interactions, thereby providing expansive insights and corroborating findings68. These methodologies adeptly manage high-dimensional datasets, prioritize variable significance, and identify latent patterns, thereby steering subsequent research endeavors. While feature selection of machine learning does not explicitly model temporal dynamics, it enhances scholarly investigations as an ancillary resource without undermining the central emphasis of Cox regression.

Our study underscores the need for a well-informed, cautious approach in antibiotic prescribing practices, ensuring that alternatives are considered where feasible, particularly for patients with heightened susceptibility. Future research should aim to refine risk stratification tools further and explore potential protective strategies in vulnerable cohorts. The findings from this study recommend that healthcare providers should be careful and explore alternative treatments for patients with multiple health issues or high risk. Public health guidelines could be improved by stressing the cautious use of fluoroquinolones, following appropriate indications, and considering patients’ overall health conditions. Moreover, these findings might inspire more research into the mechanisms of increased comorbidity risk, which could lead to preventive strategies or safer treatments. Finally, the key factors for AA/AD in patients using fluoroquinolones could be developed into an AI prediction algorithm in the future, helping to assess a patient’s risk for AA/AD before prescribing fluoroquinolones.

The present study boasts several key strengths. Firstly, utilization of a nationwide database supports the generalizability of the study results. Secondly, the sample size and follow-up duration ensured a robust collection of AA/AD events. Thirdly, we employed machine learning methods were used to pinpoint important factors for the development of AA/AD in individuals exposed to fluoroquinolones. Machine learning techniques enhance Cox regression by clarifying complex, non-linear relationships and interactions, thereby offering comprehensive insights and validating results. Lastly, the cohort study design minimized the risk of sampling bias, a common issue in case-control studies69, that most previous research has used. Despite its strengths, the current study has a few potential weaknesses. Firstly, although the NHIRD database offered a large sample size, it did not include clinical information like imaging results, biochemical and microbiological data, blood pressure readings, and physical characteristics. Secondly, the study wasn’t a randomized controlled trial, which meant that there were notable differences in the baseline characteristics of the two groups. Additionally, we used data from Taiwan’s NHIRD. However, the data does not allow us to identify which underlying diseases are treated with fluoroquinolones. To reduce these biases as much as possible, we used propensity score matching method and full multivariable adjustment model. Third, as this study was carried out with a sample from Taiwan, the generalizability of the findings to other cultural contexts or ethnic groups may be limited. Fourth, Diagnoses of aortic aneurysm or aortic dissection were based solely on ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes from Taiwan’s NHIRD. From this database, we can only determine if a patient has been diagnosed with an aortic aneurysm or dissection. However, we cannot assess the severity of the condition or whether surgery is indicated. Fifth, we were unable to confirm whether participants used fluoroquinolones before 2002 because of the limitations in our data availability and study design. Assuming that this absent data was distributed randomly across both cohorts, it is plausible that we may disregard the potential bias. Sixth, machine learning methods identified key factors for AA/AD development in individuals exposed to fluoroquinolones. However, the lack of SHAP plots70 limits the understanding the directionality of their effects due to our limited resource. These plots would provide insights into variable interactions and effect directionality, enhancing the model’s decision-making analysis and interpretability for clinical use. Conversely, the synthesis of Cox regression findings for the purpose of evaluating directionality may mitigate this limitation. Finally, a limitation lies in excluding cases with missing data rather than using imputation. While the minimal missingness likely avoided bias, methods like MissForest could have preserved data and improved robustness71. However, the small proportion of missing data in our study made exclusion unlikely to impact the results.

Conclusion

The long-term risk of AA/AD was 62% higher in patients with fluoroquinolones exposure than in those without fluoroquinolones exposure. Ten notable factors contributing to this correlation have been identified. We suggest that a sophisticated artificial intelligence system could be developed to predict the risk of developing AA/AD in patients treated with fluoroquinolone antibiotics based on our findings. Such powerful tool would enhance patient care by aiding healthcare professionals in making informed decisions regarding fluoroquinolone use.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are not available to the public because all claim records must be anonymized before they are released for analysis. The dataset is held by the Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare. (MOHW). Any researcher interested in accessing this dataset can apply for access. Please visit the website of the National Health Informatics Project of the MOHW (https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/mp-113.html). If anyone would like to request the data from this study and is having difficulty accessing it, please contact the corresponding author, T-MH, for help.

References

Majalekar, P. P. & Shirote, P. J. Fluoroquinolones: Blessings or curses. Curr. Drug Targets. 21, 1354–1370. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450121666200621193355 (2020).

van der Linden, P. D., van de Lei, J., Nab, H. W., Knol, A. & Stricker, B. H. Achilles tendinitis associated with fluoroquinolones. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 48, 433–437. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00016.x (1999).

Kaleagasioglu, F. & Olcay, E. Fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathy: etiology and preventive measures. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 226, 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.226.251 (2012).

Kapoor, K. G., Hodge, D. O., Sauver, S., Barkmeier, A. J. & J. L. & Oral fluoroquinolones and the incidence of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and symptomatic retinal breaks: a population-based study. Ophthalmology 121, 1269–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.12.006 (2014).

Wise, B. L., Peloquin, C., Choi, H., Lane, N. E. & Zhang, Y. Impact of age, sex, obesity, and steroid use on quinolone-associated tendon disorders. Am. J. Med. 125, e1223–e1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.05.027 (2012).

Singh, S. & Nautiyal, A. Aortic dissection and aortic aneurysms associated with fluoroquinolones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. 130, 1449–1457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.06.029 (2017).

Lai, C. C., Wang, Y. H., Chen, K. H., Chen, C. H. & Wang, C. Y. The association between the risk of aortic aneurysm/aortic dissection and the use of fluroquinolones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antibiot. (Basel). 10, 697. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10060697 (2021).

Sampson, U. K. et al. Global and regional burden of aortic dissection and aneurysms: mortality trends in 21 world regions, 1990 to 2010. Glob Heart. 9, 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2013.12.010 (2014).

Powell, J. T. et al. Meta-analysis of individual-patient data from EVAR-1, DREAM, OVER and ACE trials comparing outcomes of endovascular or open repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm over 5 years. Br. J. Surg. 104, 166–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10430 (2017).

Lee, C. C. et al. Risk of aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm in patients taking oral fluoroquinolone. JAMA Intern. Med. 175, 1839–1847. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5389 (2015).

Pasternak, B., Inghammar, M. & Svanström, H. Fluoroquinolone use and risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 360, k678. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k678 (2018).

Gopalakrishnan, C. et al. Association of fluoroquinolones with the risk of aortic aneurysm or aortic dissection. JAMA Intern. Med. 180, 1596–1605. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4199 (2020).

Guzzardi, D. G. et al. Induction of human aortic myofibroblast-mediated extracellular matrix dysregulation: A potential mechanism of fluoroquinolone-associated aortopathy. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 157, 109–119e102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.08.079 (2019).

Tsai, W. C. et al. Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J. Orthop. Res. 29, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.21196 (2011).

LeMaire, S. A. et al. Effect of Ciprofloxacin on susceptibility to aortic dissection and rupture in mice. JAMA Surg. 153, e181804. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1804 (2018).

Jun, C. & Fang, B. Current progress of fluoroquinolones-increased risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 21, 470. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02258-1 (2021).

Wee, I. et al. The association between fluoroquinolones and aortic dissection and aortic aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 11, 11073. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90692-8 (2021).

Daneman, N., Lu, H. & Redelmeier, D. A. Fluoroquinolones and collagen associated severe adverse events: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 5, e010077. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010077 (2015).

Maumus-Robert, S. et al. Short-term risk of aortoiliac aneurysm or dissection associated with fluoroquinolone use. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 875–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.012 (2019).

Lee, C. C. et al. Oral fluoroquinolone and the risk of aortic dissection. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 1369–1378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.067 (2018).

Sommet, A. et al. What fluoroquinolones have the highest risk of aortic aneurysm? A case/non-case study in VigiBase®. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 34, 502–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4774-2 (2019).

Sarker, I. H. AI-based modeling: techniques, applications and research issues towards automation, intelligent and smart systems. SN Comput. Sci. 3, 158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01043-x (2022).

Díez-Sanmartín, C., Cabezuelo, A. S. & Belmonte, A. A. A new approach to predicting mortality in Dialysis patients using sociodemographic features based on artificial intelligence. Artif. Intell. Med. 136, 102478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2022.102478 (2023).

Singareddy, S. et al. Artificial intelligence and its role in the management of chronic medical conditions: A systematic review. Cureus 15, e46066. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.46066 (2023).

Yin, J., Ngiam, K. Y. & Teo, H. H. Role of artificial intelligence applications in real-life clinical practice: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e25759. https://doi.org/10.2196/25759 (2021).

Coates, J. T. & de Koning, C. Machine learning-driven critical care decision making. J. R Soc. Med. 115, 236–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/01410768221089018 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Recent advances and clinical applications of deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 79, 102444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2022.102444 (2022).

An, Q., Rahman, S., Zhou, J. & Kang, J. J. A comprehensive review on machine learning in healthcare industry: classification, restrictions, opportunities and challenges. Sens. (Basel). 23, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23094178 (2023).

Zheng, J. X. et al. Interpretable machine learning for predicting chronic kidney disease progression risk. Digit. Health. 10, 20552076231224225. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231224225 (2024).

Tsai, M. H., Jhou, M. J., Liu, T. C., Fang, Y. W. & Lu, C. J. An integrated machine learning predictive scheme for longitudinal laboratory data to evaluate the factors determining renal function changes in patients with different chronic kidney disease stages. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 10, 1155426. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1155426 (2023).

Lee, W. T. et al. Data-driven, two-stage machine learning algorithm-based prediction scheme for assessing 1-year and 3-year mortality risk in chronic Hemodialysis patients. Sci. Rep. 13, 21453. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48905-9 (2023).

Shah, P. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in clinical development: a translational perspective. NPJ Digit. Med. 2, 69. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0148-3 (2019).

Hsieh, C. Y. et al. Taiwan’s National health insurance research database: past and future. Clin. Epidemiol. 11, 349–358. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.S196293 (2019).

Tsai, M. H. et al. The protective effects of lipid-lowering agents on cardiovascular disease and mortality in maintenance Dialysis patients: propensity score analysis of a population-based cohort study. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 894462. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.894462 (2022).

Alsahaf, A., Petkov, N., Shenoy, V. & Azzopardi, G. A framework for feature selection through boosting. Expert Syst. Appl. 187, 115895 (2022).

Borboudakis, G. & Tsamardinos, I. Forward-backward selection with early dropping. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 20, 276–314 (2019).

Wang, J., Xu, P., Ji, X., Li, M. & Lu, W. Feature selection in machine learning for perovskite materials design and discovery. Materials (Basel). 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16083134 (2023).

Huang, Y. C., Li, S. J., Chen, M., Lee, T. S. & Chien, Y. N. Machine-learning techniques for feature selection and prediction of mortality in elderly CABG patients. Healthc. (Basel). 9, 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050547 (2021).

Tsai, M. H. et al. Hazardous effect of low-dose aspirin in patients with predialysis advanced chronic kidney disease assessed by machine learning method feature selection. Healthcare (Basel). 9, 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9111484 (2021).

Jiang, X., El-Kareh, R. & Ohno-Machado, L. Improving predictions in imbalanced data using pairwise expanded logistic regression. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011, 625–634 (2011).

Becker, T., Rousseau, A. J., Geubbelmans, M., Burzykowski, T. & Valkenborg, D. Decision trees and random forests. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 164, 894–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2023.09.011 (2023).

Chong, W. H., Wen, D. J. R. & Goh, E. C. L. Predictors of maternal distress among mothers in economic hardship: A classification and regression tree analysis (CART). Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 92, 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000640 (2022).

Lu, R. et al. The application of multivariate adaptive regression splines in exploring the influencing factors and predicting the prevalence of HbA1c improvement. Ann. Palliat. Med. 10, 1296–1303. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-19-406 (2021).

Koh, J. Gradient boosting with extreme-value theory for wildfire prediction. Extremes (Boston). 26, 273–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10687-022-00454-6 (2023).

Ni, S. et al. Risk difference, relative risk, and odds ratio for non-inferiority clinical trials with risk rate endpoint. J. Biopharm. Stat. 33, 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10543406.2022.2065502 (2023).

Hadi, T. et al. Macrophage-derived netrin-1 promotes abdominal aortic aneurysm formation by activating MMP3 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 5022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07495-1 (2018).

Sendzik, J., Shakibaei, M., Schäfer-Korting, M., Lode, H. & Stahlmann, R. Synergistic effects of dexamethasone and quinolones on human-derived tendon cells. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 35, 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.009 (2010).

Dilme, J. F. et al. Influence of cardiovascular risk factors on levels of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 48, 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.05.023 (2014).

Sharma, C. et al. Effect of fluoroquinolones on the expression of matrix metalloproteinase in debrided cornea of rats. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 21, 6–12. https://doi.org/10.3109/15376516.2010.529183 (2011).

Tsai, W. C. et al. Ciprofloxacin-mediated Inhibition of tenocyte migration and down-regulation of focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 607, 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.02.006 (2009).

Kessler, V., Klopf, J., Eilenberg, W., Neumayer, C. & Brostjan, C. AAA revisited: A comprehensive review of risk factors, management, and hallmarks of pathogenesis. Biomedicines 10, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10010094 (2022).

Wei, L. et al. Global burden of aortic aneurysm and attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2017. Glob Heart. 16, 35. https://doi.org/10.5334/gh.920 (2021).

Howard, D. P. et al. Population-based study of incidence of acute abdominal aortic aneurysms with projected impact of screening strategy. J. Am. Heart Association. 4, e001926 (2015).

Nienaber, C. A. et al. Aortic dissection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2, 16071. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.71 (2016).

Fatini, C. et al. ACE DD genotype: a predisposing factor for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. J. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 29, 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.12.018 (2005).

Nagashima, H. et al. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor mediates vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis in cystic medial degeneration associated with Marfan’s syndrome. Circulation 104, 282–287. https://doi.org/10.1161/hc37t1.094856 (2001).

Hibino, M. et al. Blood pressure, hypertension, and the risk of aortic dissection incidence and mortality: results from the J-SCH study, the UK biobank study, and a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Circulation 145, 633–644. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.121.056546 (2022).

Heydari, A., Asadmobini, A. & Sabzi, F. Anabolic steroid use and aortic dissection in athletes: A case series. Oman Med. J. 35, e179. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2020.120 (2020).

Sendzik, J., Shakibaei, M., Schafer-Korting, M., Lode, H. & Stahlmann, R. Synergistic effects of dexamethasone and quinolones on human-derived tendon cells. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 35, 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.009 (2010).

Shantikumar, S., Ajjan, R., Porter, K. E. & Scott, D. J. Diabetes and the abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. J. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 39, 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.10.014 (2010).

Golledge, J. et al. Reduced expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients with diabetes May be related to aberrant monocyte-matrix interactions. Eur. Heart J. 29, 665–672. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehm557 (2008).

Prakash, S. K., Pedroza, C., Khalil, Y. A. & Milewicz, D. M. Diabetes and reduced risk for thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections: a nationwide case-control study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 1, 323. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.111.000323 (2012).

Li, S. et al. Diabetes mellitus lowers the risk of aortic dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Vasc Surg. 74, 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2020.12.016 (2021).

Anzai, A. et al. Adventitial CXCL1/G-CSF expression in response to acute aortic dissection triggers local neutrophil recruitment and activation leading to aortic rupture. Circ. Res. 116, 612–623. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.116.304918 (2015).

Ju, X. et al. Interleukin-6-signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 signaling mediates aortic dissections induced by angiotensin II via the T-helper lymphocyte 17-interleukin 17 axis in C57BL/6 mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 33, 1612–1621. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.112.301049 (2013).

Tomida, S. et al. Indomethacin reduces rates of aortic dissection and rupture of the abdominal aorta by inhibiting monocyte/macrophage accumulation in a murine model. Sci. Rep. 9, 10751. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46673-z (2019).

Paige, E. et al. Interleukin-6 receptor signaling and abdominal aortic aneurysm growth rates. Circ. Genom Precis Med. 12, e002413. https://doi.org/10.1161/circgen.118.002413 (2019).

Liu, X., Morelli, D., Littlejohns, T. J., Clifton, D. A. & Clifton, L. Combining machine learning with Cox models to identify predictors for incident post-menopausal breast cancer in the UK biobank. Sci. Rep. 13, 9221. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36214-0 (2023).

Mansournia, M. A., Jewell, N. P. & Greenland, S. Case-control matching: effects, misconceptions, and recommendations. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 33, 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0325-0 (2018).

Ponce-Bobadilla, A. V., Schmitt, V., Maier, C. S., Mensing, S. & Stodtmann, S. Practical guide to SHAP analysis: explaining supervised machine learning model predictions in drug development. Clin. Transl Sci. 17, e70056. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.70056 (2024).

Lee, Y. & Leite, W. L. A comparison of random forest-based missing imputation methods for covariates in propensity score analysis. Psychol. Methods. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000676 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Artificial Intelligence Center of Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital sponsored this study (2021SKHADE034).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributionsConceived and designed the experiments: W-HW, F-YW, and C-Mingchih; performed the experiments: H-YC and T-MH; analyzed the data: H-YC, C-Mingchih, J-TN, and W-HW; contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: all authors; wrote the manuscript: T-MH and W-HW; approved the manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, HW., Huang, YC., Fang, YW. et al. Investigating long-term risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection from fluoroquinolones and the key contributing factors using machine learning methods. Sci Rep 15, 13130 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97787-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97787-6