Abstract

The internal crack structure of coal significantly influences its deformation and failure. Hence, quantitatively characterizing the crack features and their evolutionary patterns in coal is crucial. This study utilized a computerized tomography (CT) system to investigate the evolution of cracks in loaded coal samples. At different stages of uniaxial compression failure, crack evolution was observed, and crack tensor theory was applied to calculate crack tensor parameters for each stage. The results show that the crack direction tensor accurately reflects the average directional characteristics of the cracks, the crack fabric tensor accurately reflects the size and damage features of the cracks, and the crack tensor can quantitatively describe the multi-dimensional characteristics of the cracks. additionally, the trace of the coal crack fabric tensor quantifies the evolution pattern of coal cracks, exhibiting a trend of slow increase, steady increase, and rapid increase. finally, an exponential function relationship was found between the trace of the coal crack tensor and stress, enabling the assessment of coal damage degree based on stress levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of China’s economy and the growing demand for strategic energy reserves, coal mining, China’s main energy source1,2, faces unprecedented challenges. As shallow coal resources gradually deplete, mining activities extend deeper below 1000 m3,4,5. Mining disturbances more easily induce dynamic disasters, such as rock bursts6,7, in coal at such depths. These dynamic failures are closely related to the expansion and evolution of internal cracks in coal. However, the crack fields within coal are complex, and there is currently a lack of sufficient quantitative methods for describing the evolution of these cracks under external loads. Therefore, quantitatively characterizing the evolution patterns of cracks during coal loading is beneficial for further revealing coal’s crack and failure mechanisms. This characterization is important for safe and efficient coal mining and underground engineering safety.

Various observation technologies have been used to study the distribution and evolution characteristics of internal cracks in coal, such as cameras8,9, optical microscopes10, and Scanning Electron Microscopes (SEM)11,12,13. However, these technologies can only observe the surface of rocks; they cannot reveal the internal crack distribution and evolution. Computerized tomography (CT) scanning technology has been widely used to investigate the internal structure of rocks14,15,16,17,18. Some scholars have utilized CT scanning technology to extract grayscale values, crack volume, and CT porosity as quantitative damage variables for the evolution of damage in coal bodies19,20. Building on this foundation, other researchers have introduced fractal dimension indicators and combined them with morphological metrics such as crack aperture and crack area to quantitatively describe the characteristics of crack evolution within rocks under various loading conditions21,22,23,24.

Quantitative characterization methods for fracture structures can be broadly categorized into morphological approaches, statistical methods, and fractal dimension theory. Morphological indices (e.g., length, area, dip angle) provide simple and intuitive descriptions of fracture characteristics. However, these indicators are overly specific with limited descriptive scope. Statistical methods are based on stochastic mathematics, statistical theory, or geological techniques like stereographic projection. They describe the overall distribution characteristics of fracture structures, but primarily reflecting macroscopic statistical features. Fractal dimension theory integrates fractal geometry with fracture geometry, deriving a comprehensive mathematical indicator: the scalar fractal dimension value. This parameter has become the most widely used fracture description index in the coal industry. Despite its strong theoretical foundation, the scalar nature of fractal dimension theory restricts its capacity to describe fracture orientation characteristics.

Tensors, as multilinear functionals, are capable of describing the multidimensional characteristics of physical quantities. Therefore, tensor-based crack description methods, such as fabric tensors and permeability tensors, have been applied to some extent25,26,27,28,29,30. Representing the multidimensional characteristics of cracks, these methods offer a more comprehensive description of rock cracks. Building on previous research, Wang et al.31,32 proposed an ellipsoid reconstruction method for coal crack fields based on CT scanning. The authors utilized crack orientation and fabric tensors to characterize the crack field, achieving notable results. Currently, crack tensors are primarily theoretical descriptions of cracks and have not yet been applied to characterize the evolutionary process of cracks. The theory of crack tensors offers a novel approach to investigating the evolutionary patterns of cracks. By using the crack tensor method, the authors analyzed the evolution of coal cracks during loading, establishing a quantitative relationship between crack tensor parameters and crack evolution characteristics. This approach is significant for explaining the failure modes and mechanical mechanisms of coal under load.

In this study, uniaxial cyclic loading and unloading tests were conducted on coal samples, with CT scans performed at different stages to obtain crack tensor parameters. By examining the evolution of coal fractures through crack tensors, the authors established a quantitative relationship between coal crack tensor parameters and stress. This provides a theoretical basis for evaluating and predicting rock dynamic disasters.

Experimental materials and setup

Coal sample preparation

The Zhao Gu Yi mine was selected due to its specific geological conditions and coal seam characteristics, which are indicative of dynamic disasters such as coal bursts. Therefore, choosing coal samples from this mine aligns with the engineering background and experimental requirements of this research. Coal samples from the Zhao Gu Yi mine at over 700 m were selected for this experiment. These samples were sourced from the same coal seam and location and underwent processing and preservation using uniform methods to minimize sample variability. Multiple cylindrical coal samples, each measuring 50 mm in diameter and 100 mm in height, were prepared. Subsequently, the coal samples were subjected to drying in a 60 °C oven at a constant temperature for 12 h and then stored in sealed bags for subsequent experimental research.

Experimental equipment and scheme

Experimental equipment

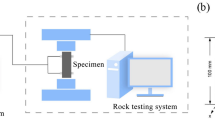

The experimental equipment used in this study includes a uniaxial compression loading system and a comprehensive CT scanning system. The uniaxial compression loading system is a pressure testing machine independently developed by the Institute of Deep Earth of the Coal Science General Institute. The system is characterized by a maximum axial load capacity of 1000 kN and a displacement loading rate range of 0.001–300 mm/min, as shown in Fig. 1A. The CT comprehensive scanning system utilizes the nanoVoxel-4000 CT scanning system produced by Tianjin San Ying Precision Instruments Co., Ltd, as shown in Fig. 1B. Samples are placed inside for scanning. The internal structure of the CT scanning system is shown in Fig. 1C, which mainly comprises an X-ray source, a loading platform, and a receiver. The principle and process of CT scanning are shown in Fig. 2.

First, the sample is placed on a rotating platform. Then, the X-ray tube emits X-rays to irradiate the sample at multiple angles continuously. As X-rays irradiate different materials, they attenuate according to Lambert–Beer’s law:

where I is the intensity of the attenuated X-rays; I0 is the initial intensity of the X-rays when they first impinge on the material; μ is the linear attenuation coefficient; μm is the mass attenuation coefficient, and x is the thickness of the material penetrated by the X-rays.

The intensity of the attenuated X-rays is directly related to density. The greater the density, the more intensely the X-rays attenuate, which appears brighter on the CT scan grayscale image. The detector captures the attenuated X-rays, forming a 2D projection image of the sample. Then, VoxelStudio Recon software is used for geometric correction, data volume filtering (optimizing the signal-to-noise ratio), beam hardening adjustment, and data reconstruction to obtain the sample’s two-dimensional slice data. Finally, the sample is regionally reconstructed in Avizo software, where the two-dimensional slice data is converted into clear, high-resolution, three-dimensional internal images.

The scanned images of this batch of coal samples were obtained via the CT scan. The schematic of the scanning slice is shown in Fig. 3A. According to the CT mentioned above scanning principle, the highest density mineral components have the most attenuation of X-rays, resulting in the brightest areas on the CT scan grayscale image. In contrast, X-rays attenuate the least when passing through pores and cracks, creating the darkest areas on the grayscale image. X-ray attenuation through the coal matrix is intermediate, making its CT scan grayscale image’s brightness level also intermediate. Hence, in Fig. 3A, the dark gray areas represent cracks, the darker gray areas represent the coal matrix, and the bright gray areas represent coal minerals.

Since the sample’s interior is relatively dense and cracks are not prominently developed, the grayscale values corresponding to each point on the yellow dashed line in Fig. 3A are extracted to clarify further the CT grayscale value differences between coal matrix, minerals, and cracks, as shown in Fig. 3B. Analysis reveals that the grayscale value shows a significant trough at point a, indicating a crack. The grayscale value is relatively stable at point b, between points A and C, representing the coal matrix. The grayscale value peaks at point c, indicating the mineral part. Therefore, the coal matrix, minerals, and cracks at different layers of the coal sample can be differentiated by their grayscale values. The CT slice images of different layers are reconstructed to obtain a three-dimensional image of the coal sample, as shown in Fig. 3C.

Experimental scheme

The determination of the CT scanning test stages references the complete stress–strain curve of coal deformation under uniaxial compressive loading, which can be divided into four stages based on the crack propagation process: densification, slow crack growth, rapid crack growth, and crack propagation to failure33. This experimental scheme divided different loading stages based on different axial stresses, thereby determining the CT scanning scheme for this experiment. Four coal specimens of the same batch and specifications were selected for uniaxial compression tests, with the peak strengths of each specimen being 20.01, 17.89, 19.52, and 22.70 MPa, respectively. After averaging, the peak strength of this batch of coal specimens was determined to be approximately 20.03 MPa. The stage scanning points for the CT scanning test were set at 0%, 25%, 50%, and 75% of the peak strength, as well as after specimen failure, corresponding to axial stresses of approximately 0, 5, 10, and 15 MPa. The CT scanning system employed spiral scanning, with main parameters including a spatial resolution of 18.36 μm, scanning voltage of 200 kV, current of 200 μA, exposure time of 0.4 s, an image merging of 2, and a frame rate of 900 fps.

Experimental process

The experimental scheme is illustrated in Fig. 4. Initially, CT scans are performed on the coal specimens in their initial state (corresponding to 0 MPa) to obtain the internal initial crack morphology and distribution characteristics. Subsequently, a loading test is conducted at a loading rate of 0.05 mm/min. When the axial load reaches the corresponding CT scanning points (corresponding to 5, 10, and 15 MPa), the loading is stopped, and unloading begins. After unloading, the specimens undergo CT scanning to obtain information on the internal crack network distribution within the coal. Finally, the specimens are loaded until complete unstable failure occurs, followed by CT scanning of the failed specimens, thereby concluding the experiment.

Results and discussion

Qualitative analysis of two-dimensional crack propagation

A qualitative description of the cracks at each stage was conducted by observing the CT scan slices of coal. Sample 1 was chosen for the analysis. The left side shows the original CT slice image with marked crack locations. The CT slice images were processed in grayscale, and the cracks were marked to mark the expanded cracks. The right side shows the crack extraction image, where the red areas represent the cracks, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5A shows the distribution of coal cracks at the initial state. Four significant inherent cracks were observed in the coal, marked as A1, A2, A3, A4, and A5, with A1 being the most prominent. Some cracks, especially A1 and A2, showed slight openings with increased external load. Coal deformation was mainly elastic at this stage, and cracks entered a stable development stage, as shown in Fig. 5B. The inherent crack A3 also showed signs of opening with further load increase and a new crack A6 appeared on the left edge of the sample. Then, crack A6 expanded and stopped at the edge of the mineral, as shown in Fig. 5C.

Further load increase caused the inherent cracks A1 and A3 to continue expanding. Similarly, crack A6 also started to expand, generating a secondary crack A7. Then, crack A7 quickly extended to the lower left corner of the sample, while inherent crack A5 nearly intersected with A1. New cracks A7 and A8 emerged and expanded towards the mineral boundary at the sample’s upper left and lower edges, as shown in Fig. 5D. The number of cracks in the sample significantly increased with further load increase, entering the unstable crack development stage of the stress–strain curve. The sample was in the post-crack stage, with multiple intersecting cracks forming a complex network, leading to coal destruction, as shown in Fig. 5E.

Scalar-based analysis of crack evolution characteristics

The qualitative description of coal crack expansion at different loading stages via two-dimensional CT slice images provides a preliminary understanding of the crack evolution process in coal under load. Avizo software was used to extract and reconstruct the coal cracks and further investigate the crack evolution characteristics of coal during loading, exploring their three-dimensional morphology and spatial distribution (Fig. 6). In addition, scalar parameters commonly used for crack description, including crack surface area, crack volume, and porosity, were employed for quantitative analysis of the crack evolution process. The crack surface area represents the extent of crack extension in space. Crack volume indicates the space occupied by cracks, and porosity is the ratio of crack volume to the total volume of the sample, reflecting the degree of coal damage. The above scalar parameters of the three-dimensional reconstructed crack field coal model were extracted using Avizo software. The scalar parameters at different loading stages are shown in Table 1 and plotted in Fig. 7.

The evolution pattern of the internal crack field at different stages was analyzed based on the data comparison of the scalar parameters of coal cracks from Table 1 combined with Figs. 6 and 7. The analysis results are as follows:

Stage I. According to Fig. 6A, the coal initially contains numerous natural pores and cracks distributed randomly and complexly, with an initial porosity of 0.206%. Some inherent cracks in the coal sample expand with an increase in load. Figure 6B shows that two inclined main crack planes at the lower end of the coal and a few small cracks at the upper end expand slightly. Moreover, new microcracks are generated inside the coal due to the axial main stress. The crack surface area increased by 40.89%, crack volume by 39.47%, and porosity by 22.33%, demonstrating a modest increase in crack scalar parameters at this stage.

Stage II. Cracks further develop as the load continues to increase. Figure 6C shows that the crack distribution in coal becomes uneven and clustered, with significant development of cracks (numerous microcracks) at the upper part. In contrast, fewer new cracks are generated at the lower part. Some horizontally oriented cracks close under axial load. At this stage, the crack surface area increased by 26.10%, crack volume by 15.70%, and porosity by 30.56%, indicating a gradual development of overall cracks.

Stage III. Inherent cracks in coal continue to develop under axial load, expanding in different directions and generating new cracks that start to intersect and connect. As shown in Fig. 6D, the cracks at the top and upper section of the coal expand significantly, with several larger crack planes starting to appear. Large crack planes also appear in the lower section of the coal. The right-side inherent crack plane develops noticeably, forming a connected area along the coal edge. The surface area of the crack plane is 5140 mm2 (accounting for 39.56% of the total crack surface area), indicating that this crack has become the main crack in the coal. At this stage, the crack surface area increased by 59.65%, crack volume by 85.42%, and porosity by 83.59%, showing rapid crack development and approaching the coal towards failure.

Stage IV: Coal reaches its strength limit under the influence of load, with the main crack plane rapidly expanding and intersecting with other cracks to form connected areas. Multiple connected crack planes appear in the coal at this point, forming a complex crack network (Fig. 6E). This network divides the coal into discrete blocks, destroying the coal. The scalar parameters of coal crack surface area, volume, and porosity all reach their maximum values.

Crack evolution characteristics analysis based on crack tensor

Crack tensor theory

Crack tensor parameters were calculated to quantitatively analyze the evolution characteristics of coal cracks at different loading stages and employ a tensor-based method for characterizing crack features. Firstly, the planar crack structures from the coal CT scans were discretized into triangular surfaces. Geomagic Wrap software was used to simplify and repair these triangular surfaces, obtaining a combination that replaces the original planar cracks. Then, a rotating flattened ellipsoid was used for the high-fidelity fitting of each triangular surface crack. This process allowed for the precise reconstruction of the internal crack field in coal using surface ellipsoids, which can then be quantitatively described using the crack tensor theory.

Two types of crack tensors were used for the quantitative description of coal crack fields at different loading stages by combining the properties of the planar crack structures in coal after CT scanning. The planar crack orientation tensor and fabric tensor are described as follows:

Planar Crack Orientation Tensor (O):

where \({\varvec{n}}_{{\varvec{\alpha}} }\) is the unit vector normal to the ellipsoid’s circular section, \({\varvec{n}}_{{\varvec{\alpha}} } = n_{{\min \left\{ {r_{V1} ,r_{V2} ,r_{V3} } \right\}}}\), Norm is matrix normalization, and λα is a weight coefficient related to the crack area, α = 1, 2, …, n.

Fabric Tensor of Cracks (F):

where \(Vi,{\varvec{\alpha}}\) represents the ith principal axis of the αth ellipsoid, \({\varvec{\alpha}} = 1,\;2, \ldots ,\;n\), \(i = 1,\;2,\;3\), and \({\varvec{n}}_{Vi,{\varvec{\alpha}} }\) is the principal axis direction vector. However, due to the characteristics of surface ellipsoids \(r_{V1} = r_{V2} \gg r_{V3}\), the fabric tensor for planar cracks can be simplified to the following:

where \(r_{{\varvec{\alpha}} }\) is the radii of the circular face of the αth ellipsoid, and \(h\) is the crack thickness. The derivation of the above formula utilizes the fact that the crack thickness is much smaller than the radii of the circular face, i.e., \(h \le r_{{\varvec{\alpha}} }\).

A two-dimensional crack tensor theory can be derived to characterize the cracks in the CT slice images by reducing the dimensionality of the three-dimensional crack tensor theory:

where O is the crack orientation tensor, F is the crack fabric tensor, nα is the direction vector of the αth linear crack (with α = 1, 2,…, n), n is the total number of cracks, Norm denotes matrix normalization, lα is the length of the αth crack, and λa is the ratio of the αth length of the crack to the total length of all cracks.

Quantitative analysis of two-dimensional crack tensor characteristics

Two-dimensional crack orientation tensors and fabric tensors of coal at different stages were obtained as follows. A series of polylines were used to fit the crack areas using the two-dimensional crack areas extracted from Fig. 5. After obtaining the coordinates of polylines vertices, coal crack orientation tensor, and fabric tensor calculation software, FTCS was utilized to derive the orientation tensor, fabric tensor, increments of the orientation tensor, increments of the fabric tensor, and the traces of each tensor for the two-dimensional cracks. The specific statistical results of these characteristic parameters are shown in Fig. 8, where the red values represent the traces of each crack tensor.

A correlation analysis was conducted between the trace of the two-dimensional crack orientation tensor (Otr_2d) and the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor (Ftr_2d/mm2) with scalar parameters of cracks to analyze the descriptive capability of the two-dimensional crack orientation tensor and fabric tensor for cracks. The scalar crack parameters primarily include the total length of the crack (L/mm), average crack direction (θ/°) (angle with respect to the horizontal), average crack width (h/mm), and crack density (fd). The Spearman rank correlation coefficient34, a non-parametric method for assessing the monotonic relationship between two variables, was used to describe the correlation between these parameters. Unlike the Pearson correlation coefficient, the Spearman correlation coefficient35 does not require the data to follow a normal distribution:

where d is the difference in the ranks of the two variables, and n is the number of data points.

The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to create the correlation heatmaps for the trace of the two-dimensional crack orientation tensor (Otr_2d) and the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor (Ftr_2d) with the total crack length (L), average crack direction (θ), average crack width (h), and crack density (fd), as shown in Fig. 9. The trace of the two-dimensional crack orientation tensor has a strictly negative correlation with the crack direction, indicating that it can describe the overall situation of the crack direction. The larger the trace of the two-dimensional crack orientation tensor, the smaller the average direction angle of cracks in the coal’s two-dimensional slice relative to the horizontal, i.e., the cracks are closer to the horizontal direction. Additionally, as seen in Fig. 8, the trace of the coal’s two-dimensional orientation tensor is relatively consistent. Moreover, the variation in the trace of the orientation tensor increment is minimal, indicating that the overall distribution of crack orientation in the coal does not significantly change during loading.

Figure 9 also reveals that the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor highly correlates with total crack length, average crack width, and crack density, with Spearman correlation coefficients higher than 0.95. The trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor positively and highly correlates with total crack length, average crack width, and crack density. This correlation suggests that the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor can encompass multidimensional features, validating the purpose of proposing the crack tensor.

The two-dimensional crack fabric tensor characterizes the scale and quantity of cracks in coal slices, indicating its suitability for describing the degree of damage in coal. Therefore, a graph illustrating the changes in the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor across different loading stages was created, as shown in Fig. 10.

According to Fig. 10, the trace of the fabric tensor of the initial crack field in the two-dimensional slice of coal is 9.5943. The fabric tensor changes with an increase in load and consequent expansion of internal cracks in the coal, increasing the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor. During the first two stages, the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor only increases by 4.25% and 9.82% due to lower stress levels, indicating a slow development of internal cracks in the coal. During Stage III, as the load further increases, the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor increases by 3.5171, a 32.02% increase compared to point 50% UCS. This significant increase in the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor indicates the rapid development of coal cracks and a higher degree of coal damage. The trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor increases by 30.3267 when entering Stage IV, i.e., a 209.12% increase from the previous stage. According to Fig. 5, many cracks converge to form a connected zone in the two-dimensional coal section, leading to complete coal destruction.

The above analysis indicates that different stress levels result in various damage characteristics in coal. The two-dimensional crack fabric tensor comprehensively reflects the degree of damage in the two-dimensional slices of coal. The relationship between the stress and the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor of coal under different stresses was established to investigate the quantitative relationship between stress and the damage level in coal. The relationship curve is shown in Fig. 11. The relationship can be expressed by an exponential function, as shown in Eq. (7):

where σ is the loading stress, and Ftr_2d is the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor of coal.

As shown in Fig. 11, the coefficient of determination (R2) for the fitting curve is 0.9995, indicating an excellent fit. This observation substantiates a strong correlation between the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor of coal and different stress levels. The damage condition of coal in two-dimensional slices can be assessed through stress levels based on the relationship given by Eq. (7).

Quantitative analysis of three-dimensional crack tensor characteristics

Quantitative analysis of crack evolution characteristics in three-dimensional space was conducted as follows. The Avizo software was used to export .obj files containing points, lines, and surface information of coal cracks. This software can automatically discretize the crack structure surfaces into multiple triangular surfaces. The .obj files were then imported into Geomagic software for further optimization and simplification. Subsequently, the FTCS software was used to obtain the directional tensor, fabric tensor, the directional tensor, increments of the fabric tensor, and traces of each tensor for the three-dimensional cracks in the coal. The specific results for these characteristic parameters are presented in Fig. 13, with the red values representing the traces of each crack tensor.

Crack orientation tensors can describe crack orientation characteristics based on the analysis of the two-dimensional crack tensor. Moreover, crack fabric tensors can describe crack size characteristics and the degree of damage. Figure 13 shows that the trace of coal’s three-dimensional orientation tensor is consistent, and the variation in the trace of the orientation tensor increment is minimal. This observation indicates that the coal’s overall distribution of crack orientation does not change significantly during loading. Instead, the crack orientation distribution aligns with the coal’s internal three-dimensional crack field pattern during loading, as seen in Fig. 6. However, the trace of the three-dimensional crack fabric tensor changes significantly and shows a clear increasing trend. Therefore, a graph illustrating the changes in the trace of the three-dimensional crack fabric tensor across different loading stages was created and shown in Fig. 13.

The following analysis can be deduced from Figs. 6, 12, 13.

Stage I. Initially, some natural cracks are distributed inside the coal. The trace of the three-dimensional crack fabric tensor is 543.5387, i.e., only 3.89% of that at point D after destruction, indicating a low initial damage level in the coal. As load is applied, internal native cracks in coal slowly expand under lower stress. The trace of the three-dimensional coal fabric tensor increases to 644.4138, i.e., by 18.56% from the initial state, indicating a minor overall change in the coal damage level.

Stage II. Internal cracks in the coal further expand with an increase in the axial load on the coal, generating some secondary cracks. The trace of the three-dimensional crack fabric tensor increases by 24.35% and enters a stable development stage, with the overall damage level of the coal still being relatively low.

Stage III. Internal cracks in the coal rapidly develop once the axial load on the coal reaches 75% of UCS. Original cracks expand quickly, and numerous new cracks emerge. The trace of the three-dimensional crack fabric tensor is 1257.8876, marking a 56.97% increase from the previous stage. The internal damage in the coal rapidly accumulates, reaching a very high level of damage.

Stage IV. As the load continues to increase to its limit, the coal reaches its compressive strength limit, and internal cracks in the coal rapidly intersect, forming connected surfaces. The coal breaks under the main crack surface. At this point, the trace of the three-dimensional crack fabric tensor is 13,975.1623, i.e., the maximum value in the entire process and nearly 26 times the initial damage state in the coal.

The relationship between the stress and the trace of the three-dimensional crack fabric tensor of coal under different stresses was established to explore the quantitative relationship between stress and the damage level in coal in three-dimensional space. The relationship curve is shown in Fig. 14. The relationship can be expressed by an exponential function, as shown in Eq. (8):

where σ is the loading stress, and Ftr_3d is the trace of the three-dimensional crack fabric tensor of coal.

As shown in Fig. 14, the coefficient of determination (R2) for the fitting curve is 0.9996, indicating an excellent fit and demonstrating a strong correlation between the trace of the three-dimensional crack fabric tensor of coal and different stress levels. The relationship provided in Eq. (9) allows for evaluating the degree of damage in coal within a three-dimensional space based on stress levels. Additionally, comparing the relationship between the trace of the two-dimensional crack fabric tensor and stress reveals that the traces of the crack fabric tensor of coal exhibit nearly identical relationships with stresses in two-dimensional and three-dimensional spaces. This relationship can be represented by an exponential relationship y = ae(bx) + c. This observation indicates that damage accumulation patterns for coal cracks are similar in two-dimensional and three-dimensional spaces. Internal cracks in coal develop slowly at lower stress levels, resulting in a gradual change in the degree of damage. However, as stress levels increase, internal cracks in coal rapidly develop, destroying the coal.

Conclusions

In this study, a computerized tomography (CT) scanning system was employed for phased observation of coal, and crack tensor theory was utilized to calculate crack tensor parameters at different loading stages. The proposed approach validated the comprehensive description capability of the crack tensor for crack characteristics. The proposed method quantitatively characterized the crack network features during coal loading. Moreover, the method analyzed the crack evolution patterns of the coal. Some conclusions can be drawn as follows:

-

(1)

By utilizing the crack orientation tensor and crack fabric tensor, we achieved a tensor-based characterization of the crack fields obtained from CT scans of coal. Spearman correlation analysis validated the effectiveness of crack tensor theory in describing the complex crack structures and their evolution in coal. This analysis demonstrated that crack tensors can quantitatively capture the multi-dimensional characteristics of cracks. Specifically, the crack orientation tensor accurately reflects the average directional features of the cracks, while the crack fabric tensor effectively represents the size and damage characteristics of the cracks.

-

(2)

The trend in the trace of the crack fabric tensor aligns with the variation patterns of scalar indicators such as crack surface area, crack volume, and porosity, all exhibiting a pattern of slow increase, steady increase, and rapid increase. This trend characterizes the damage and weakening process of coal during loading. Notably, in Stage IV, the contribution rate of the crack fabric tensor’s trace growth exceeds 85%, with crack structure feature parameters showing rapid increases and significant variations. This indicates that crack propagation and evolution predominantly occur during this stage of rock fracture.

-

(3)

We identified a clear exponential relationship between the trace of the crack fabric tensor and stress. Through curve fitting, we derived a functional expression that quantitatively relates these two variables. This relationship enables the assessment of coal damage degree based on stress levels, providing a theoretical basis for predicting coal instability and implementing underground safety early warning systems.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. email: 2921738722@qq.com.

References

Bai, X. F. et al. Coal production in China: Past, present, and future projections. Int. Geol. Rev. 60(5–6), 535–547 (2017).

Liu, M. Z., Chen, M. & He, G. The origin and prospect of billion-ton coal production capacity in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 125, 70–85 (2017).

Jiang, J. Y., Cheng, Y. P., Wang, L., Li, W. & Wang, L. Petrographic and geochemical effects of sill intrusions on coal and their implications for gas outbursts in the Wolonghu Mine, Huaibei Coalfield, China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 88(1), 55–66 (2011).

Xia, T. Q. et al. Controlling factors of symbiotic disaster between coal gas and spontaneous combustion in longwall mining gobs. Fuel 182, 886–896 (2016).

Zhu, S., Wu, S. Y., Cheng, J. W., Li, S. Y. & Li, M. M. An underground air-route temperature prediction model for ultra-deep coal mines. Minerals 5(3), 527–545 (2015).

Pan, W., Shuan-Cheng, G. & Wei, S. Roadway rock burst prediction based on catastrophe theory. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 7321–7321 (2024).

Chen, Y., Zhang, Z. K., Cao, C., Bao, S. J., Wang, S. & Xu, G. Y. Research on the causal mechanism of a rock burst accident in a longwall roadway and its prevention measures. Sci. Rep. 13(1) (2023).

Chen, P. et al. Fractal characteristics of surface crack evolution in the process of gas-containing coal extrusion. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 23(1), 121–126 (2013).

Weng, L., Li, X. B., Taheri, A., Wu, Q. H. & Xie, X. F. Fracture evolution around a cavity in brittle rock under uniaxial compression and coupled static-dynamic loads. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 51(2), 531–545 (2018).

Ni, X. M., Chen, W. X., Li, Z. Y. & Gao, X. Reconstruction of different scales of pore-fractures network of coal reservoir and its permeability prediction with Monte Carlo method. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 27(4), 693–699 (2017).

Giffin, S., Littke, R., Klaver, J. & Urai, J. L. Application of BIB–SEM technology to characterize macropore morphology in coal. Int. J. Coal Geol. 114, 85–95 (2013).

Cui, Z. D. & Han, W. G. In situ scanning electron microscope (SEM) Observations of Damage and Crack Growth of Shale. Microsc. Microanal. 24(2), 107–115 (2018).

Zhao, Y. H. Crack pattern evolution and a fractal damage constitutive model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 35(3), 349–366 (1998).

Kawakata, H., Cho, A., Yanagidani, T. & Shimada, M. The observations of faulting in westerly granite under triaxial compression by X-ray CT scan. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 34(3), 112–151 (1997).

Kawakata, H. et al. Three-dimensional observations of faulting process in Westerly granite under uniaxial and triaxial conditions by X-ray CT scan. Tectonophysics 313(3), 293–305 (1999).

Cnudde, V. & Boone, M. N. High-resolution X-ray computed tomography in geosciences: A review of the current technology and applications. Earth Sci. Rev. 123, 1–17 (2013).

Mathews, J. P., Campbell, Q. P., Xu, H. & Halleck, P. A review of the application of X-ray computed tomography to the study of coal. Fuel 209, 10–24 (2017).

Zhang, R., Ai, T., Li, H. G., Zhang, Z. & Liu, J. F. 3D reconstruction method and connectivity rules of fracture networks generated under different mining layouts. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 23(6), 863–871 (2013).

Duan, Y. T., Li, X., Zheng, B., He, J. M. & Hao, J. Cracking evolution and failure characteristics of longmaxi shale under uniaxial compression using real-time computed tomography scanning. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52(9), 3003–3015 (2019).

Li, Y. Y., Cui, H. Q., Zhang, P., Wang, D. K. & Wei, J. P. Three-dimensional visualization and quantitative characterization of coal fracture dynamic evolution under uniaxial and triaxial compression based on μCT scanning. Fuel 262, 116568 (2020).

Wang, D. K. et al. Dynamic evolution characteristics and fractal law of loaded coal fracturesby micro industrial CT. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 39(6), 1165–1174 (2020).

Jing, Y., Armstrong, R. T., Ramandi, H. L. & Mostaghimi, P. Topological characterization of fractured coal. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122(12), 9849–9861 (2017).

Zhou, H. W., Zhong, J. C., Ren, W. G., Wang, X. Y. & Yi, H. Y. Characterization of pore-fracture networks and their evolution at various measurement scales in coal samples using X-ray μCT and a fractal method. Int. J. Coal Geol. 189, 35–49 (2018).

Zhang, Y. B. et al. Quantitative characterization and mesoscopic study of propagation and evolution of threedimensional rock fractures based on CT. Rock Soil Mech. 42(10), 2659–2671 (2021).

Kachanov, M. Continuum model of medium with cracks. J. Eng. Mech. Div. 106(5), 1039–1051 (1980).

Oda, M. A method for evaluating the effect of crack geometry on the mechanical behavior of cracked rock masses. Mech Mater. 2(2), 163–171 (1983).

Ken-Ichi, K. Distribution of directional data and fabric tensors. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 22(2), 149–164 (1984).

Snow, D. T. Anisotropie permeability of fractured media. Water Resour. Res. 5(6), 1273–1289 (1969).

Yang, Q., Chen, X. & Tham, L. G. Relationship of crack fabric tensors of different orders. Mech. Res. Commun. 31(6), 661–666 (2004).

Yang, Q., Chen, X. & Zhou, W. Y. Effective stress and vector-valued orientational distribution functions. Int. J. Damage Mech. 17(2), 101–121 (2007).

Wang, S. G., Shen, J. R. & Mu, P. Y. Effect of natural crack distributions on coal failure process based on fluorescent epoxy impregnation method and phase-field FEM simulation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82(8), 304 (2023).

Wang, S. G., Mu, P. Y., Wang, J. M., Li, H. T. & Qi, Q. X. Ellipsoidreconstruction and tensor characterization of planarfractures in coal obtained by CT-scanning and the applications. J. China Coal Soc. 47(7), 2593–2608 (2022).

Li, X. S., Wang, Q., Wu, K. B., Wang, J. M. & Qi, Q. X. Microscopic fracture evolution and propagation mechanism of coal with high coal burst liability. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 130, 104331 (2024).

Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Int. J. Epidemiol. 39(5), 1137–1150 (2010).

Pearson, K. Notes on the history of correlation. Biometrika 13(1), 25–45 (1920).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the sponsorship from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52204094, 52374206) and the Open Research Fund Program of State key Laboratory of Hydroscience and Engineering (sklhse-2023-D-03).

Funding

The authors wish to acknowledge the sponsorship from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52204094, 52374206) and the Open Research Fund Program of State key Laboratory of Hydroscience and Engineering (sklhse-2023-D-03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pengyu Mu: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. Shouguang Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Funding—review and editing. Jiamin Wang: Methodology, Validation, Data Curation—review and editing. Jiarong Shen: Investigation, Data Curation. Xiangshang Li: Investigation, Formal analysis—review and editing. Huaguang Liu: Investigation. Yulong Chen: Formal analysis—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mu, P., Wang, S., Wang, J. et al. Quantitative characterization and evolutionary patterns of coal cracks based on crack tensor analysis. Sci Rep 15, 12489 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97805-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97805-7