Abstract

The primary aim of this investigation is to fabricate a novel nano-catalyst by anchoring copper iodide onto magnetized graphene oxide and modifying it with a new ligand of N'1,N'3-bis(2-aminobenzoyl)benzene-1,3-disulfonohydrazide (ABDSH). The performance of this nano-catalyst demonstrated remarkable efficacy and selectivity. The synthesized nanocomposite was characterized using FTIR, EDX, MAPPING, FESEM, VSM, TGA, and DSC techniques. Results indicated that this nanocomposite possessed favorable morphology, facile preparation, high catalytic activity, and substantial surface area. Furthermore, the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite was employed as a recyclable heterogeneous catalyst for green synthesis of pyrazole derivatives. Noteworthy advantages of this reaction encompass its solvent-free conditions, straightforward purification process, cost-effectiveness, attainment of high product yields, synthesis of new pyrazole derivatives, minimal reaction durations, and simple operational procedures. Moreover, the proposed GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI heterogeneous catalyst demonstrated excellent stability and reusability over four consecutive cycles, aligning with the principles of green chemistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, there has been increasing interest in green approaches for developing synthetic routes, driven by the need to minimize waste generation, reduce energy and raw material consumption, and utilize non-toxic, renewable, or biodegradable materials. This shift toward green chemistry aims to design chemical products and processes that safeguard both human health and the environment1,2. Guided by the twelve principles established by Anastas and Warner, green chemistry offers essential guidelines for chemists in material synthesis, the development of new compounds, and technological advancements3,4,5. The synthesis of recyclable magnetic catalysts aligns with the principles of green chemistry, which emphasize the development of sustainable, resource-efficient, and environmentally friendly processes6,7,8,9.

Graphene Oxide (GO) is a derivative of graphene that incorporates oxygen-containing functional groups, including hydroxyl, epoxy, and carboxyl groups. These functional groups significantly improve its hydrophilicity, enabling GO to disperse easily in water and other polar solvents. With its distinctive structure, GO offers adjustable electrical conductivity, a large surface area, and remarkable mechanical strength. Its versatility makes it valuable in diverse applications such as energy storage, water treatment, catalysis, and biomedicine10,11,12. Additionally, the abundance of oxygen functionalities allows for further chemical modifications, enhancing its potential for the development of advanced materials13,14,15. Combining graphene oxide with iron nanoparticle (MGO) creates a hybrid material with enhanced magnetic properties, high surface area, and improved adsorption capacity, making it highly effective for applications in water purification, catalysis, and environmental remediation16. Iron nanoparticles offer significant potential as catalysts, thanks to their low cost, high reactivity, and strong environmental stability17,18,19. Researchers today are increasingly focused on metal nanoparticles, their role as catalyst sites, and their use as supports in catalytic processes20,21,22 . The MGO catalysts have revolutionized nano-catalysis, driving a dramatic increase in research activity. This synergy has spurred advancements in diverse fields such as graphene-supported nanostructures, organic chemistry, electrochemical processes, and phytochemical reactions, resulting in the publication of hundreds of research papers each year23,24,25. MGO has recently been applied as a catalyst in various fields, including the synthesis of tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyrans26, 2,4,6-triarylpyridines27, and biodiesel from soybean oil28. Additionally, Cu(I) nanoparticles on polydopamine-encapsulated GO/Fe3O4 have been developed as recyclable nano-catalysts for nitroarene reduction29.

The synthesis of heterocyclic compounds via one-pot multicomponent reactions (MCRs) has garnered significant attention due to its efficiency, versatility, and ability to generate complex structures in a single step. These reactions involve the simultaneous interaction of multiple reactants to form a heterocyclic ring structure30,31. This strategy streamlines synthetic pathways, reducing the need for isolation and purification of intermediates, which is particularly advantageous in the context of drug discovery, material science, and fine chemical production. Their growing appeal is attributed to their straightforward experimental procedures, cost-effectiveness, and significantly reduced reaction times, making them highly accessible and efficient for various applications32,33,34,35.

Carbon- heteroatom bond formation is a fundamental reaction in modern organic synthesis, and serves as a powerful tool for producing various pharmaceutical and biologically significant compounds. Among these, the synthesis of pyrazole and its derivatives has gained prominence due to their diverse medicinal properties and significant role in organic synthesis36,37,38,39. Pyrazoles exhibit a wide range of biological activities, including antipyretic, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antidepressant, anticancer, antiproliferative, antioxidant, antibacterial, and antimicrobial effects. Owing to their extensive chemical and biological importance, pyrazole synthesis has drawn considerable interest from organic chemists40,41,42,43,44. In the past, a variety of catalysts have been employed for pyrazole synthesis, including 3-aminopropylated silica, tetraethyl ammonium L-prolinate45, ZnO NPs/microwave irradiation (MWI)24, sulfuric acid gene46, Zr@guanine@MCM-41 NPs47, light radiation48,[Et3NH][HSO4]49 and polyethylene glycol sulphurated (PEG-SO3H)50. Many of these methods are characterized by extended reaction times, low yields, and poor catalyst efficiency. Therefore, there is an ongoing need for simpler and milder approaches to pyrazole synthesis.

This study focuses on the development of a novel heterogeneous catalyst, GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI, utilizing graphene oxide as the base material. The N'1,N'3-bis(2-aminobenzoyl)benzene-1,3-disulfonohydrazide ligand was covalently attached to magnetized graphene oxide surfaces via a 3-chloropropyltrimethoxysilane linker. This catalyst was subsequently employed in the eco-friendly synthesis of various pyrazoles through one-pot two-component reactions (various benzaldehyde derivatives and 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-perizole-3-one) and three-component reactions (various benzaldehyde derivatives, 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-perizole-3-one, and 4-hydroxycoumarin). The results highlight the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI’s exceptional efficiency, enabling rapid reaction rates and achieving high to excellent product yields within short reaction times (Fig. 1).

Experimental

General

All chemicals used in this study, solvents, reagents, and precursors, were purchased from Merck and Aldrich and were utilized as received, without any additional purification. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT–IR) analysis was performed using a Perkin Elmer GX spectrometer to identify functional groups and confirm the presence of key chemical bonds. Spectra were recorded in the 400–4000 cm−1 range. FESEM imaging was carried out using an FE–SEM TESCAN MIRA3 instrument to analyze the surface morphology and particle distribution of the catalyst. Elemental composition and EDX analysis were performed using an EDAX–EDS spectrometer, providing insight into the elemental distribution within the synthesized material. Thermal stability and decomposition behavior were evaluated through TGA and DSC analysis, performed on a TGA–DTA instrument under a nitrogen (N2) atmosphere. The heating rate was maintained at 10 °C/min, covering a temperature range of 25–600 °C. Magnetic property analysis was conducted using vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) with a Lakeshore 740 magnetometer. The magnetic behavior of the synthesized nanocomposite was examined at each stage of synthesis, and the magnetization values were compared to evaluate the impact of different components on the overall magnetic properties. The progress of reactions and the purity of products were checked through TLC. The structural elucidation of the synthesized products was carried out using 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR) spectroscopy. These analyses were conducted on Bruker BioSpin GmbH 300 MHz FT–NMR spectrometers, using DMSO-d6 as the deuterated solvent to ensure optimal signal resolution. The melting points of the synthesized compounds were determined using a BUCHI 510 melting point apparatus with the open capillary tube method to assess their thermal stability and purity. Additionally, the progress of the reactions and the purity of the synthesized products were monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC), performed on silica gel plates with appropriate solvent systems.

Synthesis of graphene oxide (GO)

The synthesis of GO followed a modified version of the Hammer’s method. The procedure began by placing a 250 mL flask in an ice bath to maintain a low reaction temperature, followed by the careful preparation of a mixture containing 50 mL of 98% sulfuric acid and 0.5 g of graphite, ensuring thorough homogenization. After 15 min, 2 g of potassium permanganate (KMnO4) was gradually added to the mixture over 2 h while stirring vigorously to prevent overheating and ensure uniform oxidation. Following three hours of reaction time, 150 mL of distilled water was slowly added. After 30 min, 10 mL of 30% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was added dropwise, leading to a color change indicating the reduction of excess permanganate. The resulting mixture was subjected to sequential washing with 5% hydrochloric acid (HCl) and deionized water to remove residual metal ions and acidic impurities. The final purification was carried out through multiple washing cycles using centrifugation, ensuring the complete removal of contaminants. The purified GO was then dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h to obtain the final product51.

Synthesis of GO/Fe3O4

40 mg of GO was prepared in 40 mL of distilled water and subjected to ultrasonication for 30 min to ensure proper exfoliation and dispersion. Subsequently, a solution containing 0.21 mmol of FeCl2·4H2O and 0.4 mmol of FeCl3·6H2O in 50 mL of water was added, and the mixture was stirred magnetically. Then, the reaction mixture was brought to a temperature of 85 °C, followed by the gradual addition of a 30% ammonium solution until the solvent reached a pH of 10, facilitating the in-situ formation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on the GO surface. Afterward, the resulting mixture underwent washing for 45 min, followed by separation using a centrifuge and multiple washes with hot water to remove residual impurities. The product was then dried for 24 h at 60 °C in an oven51.

Synthesis of magnetized graphene oxide coated with 3-chloropropyltrimethoxysilane (GO/Fe3O4@PTMS)

A solution of 200 mg of GO/Fe3O4 in 30 mL of toluene was subjected to ultrasonication for 30 min to achieve dispersion to achieve uniform dispersion. Subsequently, 15 mL of PTMS was added to the mixture, and the resulting solution was refluxed for 24 h with magnetic stirring, allowing the successful grafting of PTMS onto the GO@Fe3O4 surface. Upon the completion of the reaction process, the magnetic nanoparticles were effectively isolated from the reaction mixture through the utilization of a super-magnet, following the isolation process using a super-magnet, the magnetic nanoparticles underwent thorough washing procedures, involving three successive washes with toluene and two additional washes with ethanol, each wash comprising a volume of 3 mL, to ensure the complete removal of residual impurities and unreacted reagents. The washed nanoparticles were then dried for 24 h at 60 °C in an oven13.

Synthesis method of ligand: N'1,N'3-bis(2-aminobenzoyl)benzene-1,3-disulfonohydrazide (ABDSH)

In a 50 mL bottle containing 3 mmol 1,3-benzendisolfonyl chloride (1,3-benzendisolfonyl chloride was synthesized in accordance with the procedures described in previous studies51) was dissolved in 20 mL of acetonitrile, and then 6 mmol of 2-aminobenzene hydride was added to the reaction container, and it was also stirred for 24 h in reflux conditions. After the reaction was completed the reaction mixture was separated using a centrifuge, followed by triple washing with acetonitrile and a subsequent wash with ethanol. Subsequently, the material was dried in a 60 °C oven to remove residual solvents.

Synthesis catalyst of copper iodide immobilized on magnetic graphene oxide coated with ABDSH ligand (GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI)

To initiate the catalytic synthesis process, 0.5 g of activated graphene bearing Ligand the ABDSH (GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI) and 350 mg of copper iodide (Copper iodide was synthesized following the methods outlined in earlier studies52) were introduced into a 40 mL EtOH solution and then subjected to reflux conditions for 24 h. Upon completion of the catalytic reaction, GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI was retrieved using an external magnet and was washed multiple times with EtOH (3 × 3 mL) to remove residual unreacted species. Subsequently, it was dried for 24 h at 60 °C in an oven. The catalytic synthesis method is shown in Fig. 2.

General method for the synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) derivatives in the presence of GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite

In a test tube, 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-perizole-3-one (2 mmol), aromatic aldehyde (1 mmol), and GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nano-catalyst (0.05 g) were injections and also exposed to magnetic stirred for a reasonable period of time at a temperature of 55 °C. The progression of the reaction with TLC (n-hexane/ethyl estate: 9/2) was examined, after the completion of the reaction and the formation of the intended compound, the mixture was cooled to room temperature, then, in order to separate the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI, 3 mL of chloroform or hot EtOH was added to the mixture, and was stirred for 2 min, Subsequently, the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite were extracted from the reaction vessel using an external super magnet, followed by rinsing with EtOH, then subjected to drying in an oven at 60 °C. The reaction solvent was evaporated and the products were nebulized with EtOH and the compounds were synthesized with high yield. FTIR, 1HNMR and 13CNMR spectra were used to identify the products and the melting point of all products was taken.

General method for the synthesis of 3-((phenyl)(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methyl)-4-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-ones derivatives in the presence of GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite

In a test tube, 4-hydroxycoumarin (1.0 mmol), 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one (1 mmol) and derivatives of aromatic aldehydes (1 mmol) and GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@Cu nanocomposite (0.05 g) were stirred with a magnetic stirrer for an appropriate time at 70 °C. The advancement of the reaction was monitored using TLC (n-hexane/ethyl acetate: 9/2). Upon the reaction’s completion and the formation of the desired compound, the mixture was cooled to room temperature. Then, in order to separate the catalyst, 3 mL of chloroform or hot EtOH was added to the reaction mixture and stirred for 2 min, and the catalyst was insoluble, so the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite was removed from the reaction vessel with an external super magnet, then washed with EtOH and placed in an oven with a temperature of 60 °C to dry and the solvent of the reaction mixture was evaporated and the products were nebulized with EtOH and the compounds were synthesized with high yield. FTIR, 1HNMR and 13CNMR spectra were used to identify the products and the melting point of all products was taken.

Results and discussion

Spectroscopy to identify the copper iodide catalyst immobilized on magnetic graphene oxide coated with N’1,N'3-bis(2-aminobenzoyl)benzene-1,3-disulfonyl hydrazide ligand ABDSH (GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI)

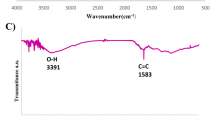

After the catalyst synthesis, various analyzes including FT–IR, (FESEM), EDX, MAPPING, thermal decomposition analysis (DSC, TGA) and Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) was studied to confirm and identify GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI catalyst. Figure 3 shows FT–IR spectrum (a) graphene oxide, (b) magnetized graphene oxide (GO/Fe3O4) (c) magnetized graphene oxide functionalized with 3-chloropropyltrimethoxysilane (GO/Fe3O4@PTMS), (d) (ABDSH), (e) ligand placed on graphene oxide (GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH) and (f) catalyst of GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI. In part (a), concerning graphene, the spectrum exhibits a prominent peak around 3406 cm−1, attributed to stretching vibrations, while the peak at 1230 cm−1 corresponds to bending vibrations associated with hydroxyl groups present on the GO surface.

O–H groups of COOH of GO are confirmed by a broad peak starting at 2500 cm−1. The C = O stretching vibration of the COOH group appeared in 1728 cm−1. The aromatic carbons constituting the graphite skeleton, devoid of oxidation, remain integral within the structural framework, are located in the region of 1626 cm−153,54. Part (b) shows GO@Fe3O4 hybrid nanoparticles that the intensity of the peaks at 3400–3500 cm−1 and 1728 cm−1 corresponding to the hydroxyl and acidic groups on graphene has decreased. Peaks of Fe–O group appeared at 594 and 620 cm−1, this observation serves as confirmation of the existence of iron nanoparticles55,56. In part (c) of the spectrum, the surface of magnetic graphene oxide is subjected to functionalization with 3-chloropropyltrimethoxysilane, resulting in the emergence of a peak at approximately 2953 cm−1, indicative of the stretching vibrations of aliphatic bonds associated with CH3-PTMS, strategically positioned atop the magnetic graphene nanosheets, while part (d) showcases the spectrum corresponding to the ABDSH ligand. The broad peak, discernible in the region of 3359 cm−1, is attributable to the stretching vibrations of the NH groups of the ABDSH ligand, whereas the stretching vibrations of the S = O group are visibly evident in the spectral regions of 1129 cm−1 and 1331 cm−1. Part (e) corresponds to the placement of ABDSH ligand on the surface of GO/Fe3O4@PTMS. The peaks related to the ligand are observed in this part, encompasses a broad peak associated with the stretching vibrations of NH groups, appearing around 3496 cm−1, and the stretching vibrations of the S=O group are observed in the regions of 1163 and 1335 cm−1, which have shifted higher compared to part (d). The peak appearing at 2956 cm−1 corresponds to the CH group of PTMS. Part (f) is related to the placement of nano copper on the surface of the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI, the stretching vibrations of NH and S = O groups have decreased, which indicates their overlap with nanomaterials.

The elemental composition of the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI composite was extensively examined using Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis (Fig. 4). Distinct peaks corresponding to key elements such as carbon (C), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), silicon (Si), iron (Fe), sulfur (S), copper (Cu), and iodine (I) were identified, confirming the successful immobilization of copper iodide (CuI) onto the surface of the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH composite. These results are consistent with the expected composition of the material.

A detailed elemental composition table is presented in Fig. 4, which outlines both the weight percentage and atomic percentage of each element in the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite. This table provides valuable insights into the distribution of elements within the catalyst. For instance, the copper content was found to be 10.23% by weight and 3.48% by atomic percentage. The iron content, measured at 7.5% by weight, corresponds to an atomic percentage of 2.46%. Carbon, primarily associated with graphene oxide, accounted for 32.29% by weight and 57.12% by atomic percentage, reflecting its significant presence in the composite. Additionally, oxygen and nitrogen were found at weight percentages of 17.58% and 6.15%, respectively. Overall, the elemental weight and atomic percentages presented in Fig. 4 align with the expected composition for the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite, confirming its successful synthesis and composition consistency. Furthermore, elemental mapping analysis, as depicted in Fig. 5, reaffirms the presence of all anticipated elements within the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI 's structure, including O, C, Fe, N, Si, copper, and iodine.

Thermal stability assessment of the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI was meticulously carried out through the utilization of thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), techniques indispensable for evaluating the catalyst’s performance under varying temperature conditions. (Fig. 6). The TGA analysis revealed distinct mass reduction stages with increasing temperature. The initial mass loss observed at temperatures below 200 °C is attributed to the evaporation of water molecules and residual organic solvents retained within the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI. Subsequently, as the temperature rises, a notable weight reduction occurring at approximately 330 °C signifies the decomposition and dissolution of organic groups within the system, indicating the thermal behavior of the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI at elevated temperatures. These findings collectively affirm the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI’s stability up to 330 °C. Moreover, the DSC curve corroborated the results obtained from the TGA analysis.

The synthesis of the composite is contingent upon the properties of the filler nanoparticles and their dispersion within the composite matrix, a process that serves to augment its chemical, thermal, physical, and electrochemical attributes, thereby contributing significantly to its overall performance and functionality. Morphological analysis, structural examination, and size assessment of GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI particles were comprehensively conducted utilizing field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), a technique essential for investigating the intricate details of catalyst morphology, structure, and particle size distribution (Fig. 7). Part A concerns graphene oxide, characterized by its folded and layered graphene surface. Part B illustrates magnetized graphene oxide, enveloping iron particles atop the graphene surface. Part C pertains to magnetic graphene oxide functionalized with PTRMS, displaying silica and iron particles dispersed evenly across its surface. The D parts correspond to GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI, displayed at different scales. The D1 and D2 parts clearly illustrate the ligand structure on the graphene oxide surface, arranged in regular geometric shapes. Additionally, the images demonstrate the high and uniform dispersion of copper nanoparticles on the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI’s surface.

The synthesized catalyst’s magnetic properties are pivotal as they are essential for enabling its easy retrieval from the reaction mixture and subsequent reuse, playing a crucial role in ensuring efficiency in the recycling process and enhancing the overall practicality and utility of the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI. To evaluate these properties, Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM) analysis was conducted. Figure 8 presents the VSM curves of various samples, including (a) GO@Fe3O4, (b) GO@Fe3O4@PTMS, (c) GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH, and (d) the synthesized GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite. Examination of the figure reveals a gradual decrease in magnetic properties with layering, indicative of optimal layer placement. Specifically, the magnetic value of the GO@Fe3O4 sample registers at approximately 40 emu/g. Upon the introduction of 3-chloropropyltrimethoxysilane onto GO@Fe3O4, the magnetic value decreases to about 20 emu/g. Subsequent processes, including ligand immobilization and copper metal deposition on GO@Fe3O4@PTMS, result in further reductions in magnetic values to 11 and 6 emu/g, respectively. These nanocomposites exhibit remarkable ease of separation from the reaction medium using a super magnet, as illustrated in Fig. 9. These images validate the VSM analysis and underscore the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI’s effortless recoverability.

Catalytic application of the GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@Cu in the preparation of 4-(arylmethylene) bis-(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol) derivatives and 3-((phenyl)(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methyl)-4-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-ones

Following confirmation of the synthesis of the new nano-catalyst, the catalytic activity was assessed through the synthesis of 4-(arylmethylene) bis-(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol) derivatives. Initially, model substrates, 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one (2.0 mmol), and 4-chloro-benzaldehyde (1.0 mmol), were selected for evaluation. Various reaction conditions, including different solvents (water, ethanol, water/ethanol, methanol, acetonitrile, and solvent-free), temperatures, and the GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@Cu amounts, were investigated (Table 1). The reaction in different solvents and in the presence of GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI showed that the yield of the reaction in different solvents depends on factors such as solvent polarity, solubility of reactants, interaction with the catalyst, and stabilization of intermediates or transition states. In this reaction, polar solvents like ethanol and methanol enhanced the reaction efficiency, while water showed negligible efficiency. This could be due to the following reasons: the reactants and/or the catalyst (GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI) might not be sufficiently soluble in water. If the reactants do not dissolve properly, the reaction cannot proceed efficiently. The catalyst might have hydrophobic regions that are not well-dispersed in water, leading to reduced catalytic activity. Water might interact with the active CuI catalytic sites, leading to deactivation through hydrolysis or oxidation, also Water molecules can strongly coordinate with CuI, reducing its availability for catalyzing the reaction. While ethanol and methanol provide a suitable environment for stabilizing intermediates, water might not stabilize the key transition states or reactive intermediates effectively. Thus, although water is a polar solvent, its specific interactions with the catalyst and reactants could be responsible for the negligible efficiency observed. The highest efficiency was obtained in solvent-free conditions. Also, different temperatures were evaluated, and with the increase in temperature, an increase in reaction efficiency was observed, and the optimum temperature was obtained at 55 °C. In addition, different amounts of GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI were examined, and the results indicated an increase in efficiency by increasing the amount of GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI up to 50 mg. Optimal conditions were identified as 50 mg of GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI, solvent-free, at 55 °C, yielding significantly improved product yields compared to reactions without the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI. Table 2 presents the investigation of the model reaction using various GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI intermediates. The reaction conducted in the presence of graphene oxide alone yielded a negligible product after 20 min. However, magnetizing the graphene oxide increased the reaction yield to 80% and reduced the reaction time to 10 min. Functionalizing the surface of magnetic graphene oxide with PTRMS decreased the product yield to 46% and extended the reaction time to 20 min. Subsequent functionalization of the GO/Fe3O4@PTMS surface with a the ABDSH ligand improved the reaction efficiency to 72%, with the reaction time remaining at 20 min. Further modification by fixing CuI on the GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH surface significantly enhanced the reaction efficiency to 95% and reduced the reaction time to 6 min. Additionally, the model reaction was performed in the presence of Fe3O4 and copper iodide, which resulted in yields of 86% and 61%, respectively. Furthermore, Table 3 showcases different synthesized derivatives of 4-(arylmethylene)bis-(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol)s. In a related study, using the GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nano-catalyst, various derivatives of 3-((phenyl)(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methyl)-4-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-ones were synthesized. Initially, the model substrates comprising 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one (1.0 mmol), 4-hydroxycoumarin (1.0 mmol), and 4-chloro-benzaldehyde (1.0 mmol) were specifically chosen for the purpose of assessing the reaction conditions. Exploring the model reaction was conducted in different reaction conditions, including different solvents (water, ethanol, water/ethanol, methanol, acetonitrile and no solvent), temperature and different amounts of the GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI (Table 4). Different and new derivatives were synthesized under optimal conditions solvent-free, 70 °C and 50 mg of the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI. (Table 5).

The findings indicate excellent GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI performance and rapid reaction duration. From Tables of 3 and 5, it can be seen that the electron acceptor and donor groups on benzaldehyde do not have a significant effect on the performance of the targeted outcome. However, electron-withdrawing groups yield products within a shorter reaction period, while donor groups necessitate an extended duration.

The Hammett equation is a mathematical relationship in physical organic chemistry that correlates the rates or equilibria of chemical reactions with the electronic properties of substituents on aromatic rings or carbon–carbon double bonds. Figure 10 with two parts A and B related to the Hammett diagram, synthesis of 4,4'-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) and 3-((phenyl)(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methyl)-4-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-ones derivatives shows respectively. The slope of the two-reaction graph equation suggests that the reaction rate or equilibrium position increases with the electron-withdrawing nature of the substituent, but these indicate that electronic effects do not play a large role in the reaction. It can be deduced from the slope of the graphs, it can be concluded that the effect of the substituent groups in the synthesis reaction of 4,4'-(arylmethylene) bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) (part a) is greater than their effect in the synthesis of 4-((4-Hydroxy-2-oxo-2H-chroman-3)-yl)(phenyl)methyl)-5-methyl-2-phenyl-1,2-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-ones (Part b).

The suggested mechanism elucidating the catalytic function of GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite in the preparation of derivatives 4-((4-chlorophenyl)methylene)-bis-(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol)s and 3-((phenyl)(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methyl)-4-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-ones is presented in Figs. 11 and 12, respectively. The GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nano-catalyst functions as a Lewis acid, playing a crucial role in promoting the reaction. It facilitates the process by interacting with the non-bonding electron pairs on the oxygen atom (carrying a negative charge), thereby polarizing the reactants and enhancing their reactivity. This electron-withdrawing effect aids in the activation of the reactants, making them more susceptible to the subsequent chemical transformations. As shown in Fig. 11, first, the interaction of the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI with the electrons of the oxygen atom in benzaldehyde provides an active nucleophilic site for the attack of 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one. The reaction between active aldehydes and 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one produces intermediate A. Intermediate B arises following the elimination of a water molecule, then in the vicinity of the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI, intermediate B reacts with the enol form of 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazole-3-one and intermediate C is formed, then following tautomerization, Upon completion of the reaction, the product is formed48,57,58, and subsequently, the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI is reclaimed for subsequent use. Figure 12 shows a similar proposed mechanism in the presence of GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nano-catalyst for the synthesis of 3-((phenyl)(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methyl)-4-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-ones as is clear from the Figure. In the initial step, the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI initiates interaction with the electrons of the oxygen atom in benzaldehyde, thus creating an active nucleophilic site conducive for the subsequent attack of 4-hydroxycoumarin. The reaction between active aldehydes and 4-hydroxycoumarin produces intermediate A ntermediate B forms when a water molecule is removed from Intermediate A. It then reacts with the enol form of 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one in the presence of GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI, and the formation of intermediate C59. Subsequent tautomerization results in the final product, while GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI is recovered for reuse. These processes are a demonstration of how the nano-catalyst, through its unique structure and Lewis acidic properties, improves both the efficiency and selectivity of the reaction.

Catalyst recovery is a critical aspect of catalytic performance assessment. To assess this, ethanol or chloroform was added to the reaction mixture following the model reaction to facilitate catalyst recovery, and the mixture was stirred for 2 min using a magnetic stirrer. Using an external magnetic system, the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI promptly extracted from the reaction container. Subsequently, it underwent multiple wash cycles with ethanol before being subjected to drying at 60 °C for 24 h. Following this process, the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI was reintroduced into the model reaction. The results demonstrated that the catalyst retained nearly consistent activity, highlighting its durability and stability (Fig. 13). However, a decline in reaction efficiency was observed after the fourth cycle, which may be attributed to the gradual reduction of copper on the surface of the GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite. Since copper serves as the primary active site for the reaction, its depletion likely contributed to the diminished catalytic performance. Additionally, while iron is present and plays a supportive role in facilitating the reaction, some loss of both copper and iron may have occurred during the washing and recycling steps, further impacting the catalyst’s effectiveness. These findings suggest that while the catalyst is robust and reusable for multiple cycles, its activity may gradually decline due to elemental loss over repeated use. Figure 14a,b display the FESEM and VSM analyses of the recycled catalyst, respectively, highlighting its physical and magnetic properties. The FESEM images of the recycled catalyst after four cycles demonstrate minimal changes compared to the original catalyst, suggesting that its surface morphology and structure remain largely unaffected by the repeated catalytic cycles. On the other hand, the VSM analysis indicates that the magnetism of the recycled catalyst is approximately 5 emu (electromagnetic units), a value deemed acceptable for catalytic applications. This level of magnetism ensures that the catalyst can be easily separated from the reaction mixture using an external magnet. However, a slight decrease in magnetism is observed in the recycled catalyst, which can be attributed to the loss of iron particles during the washing process. Despite this minor reduction in magnetism, the catalyst retains its overall functionality, confirming its stability and durability for extended use in catalytic reactions.

A comparison is made between the effectiveness of the new recyclable heterogeneous catalyst and other catalysts in the synthesis of 4-(arylmethylene)bis-(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-yl)s and 3-((phenyl)(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methyl)-4-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-ones, and the results of this comparison are summarized in Tables 6 and 7. Table 6 demonstrates that the GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite exhibits higher efficiency compared to the other catalysts in the synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis-(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol) derivatives, formed from the condensation of benzaldehydes and 5-pyrrolidine. The products were synthesized in a shorter time of 4 to 12 min with yields ranging from 90 to 95% under solvent-free conditions. In contrast, other catalysts typically required longer reaction times, higher temperatures, and resulted in lower yields. Table 7 specifically highlights the performance of various catalysts in synthesizing 3-((phenyl)(5-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methyl)-4-hydroxy-2H-chromen-2-ones. One such catalyst, zinc oxide nanoparticles, was employed under solvent-free conditions at 120 °C, yielding 80–90% of the target compounds within 20–35 min through the condensation of aryl aldehydes, 4-hydroxycoumarin, and 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one. In a similar study, the same derivatives were synthesized in water at 80°C, achieving yields of 84–92% within 25–40 min. In contrast, the present GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI nanocomposite demonstrated superior efficiency by synthesizing these derivatives at a lower temperature (70 °C), in a shorter reaction time (9–17 min), and with higher yields (88–93%), all without the need for a solvent. As shown in Tables 6 and 7, the GO/Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI, functioning as an effective, environmentally friendly, and reusable catalyst, it facilitated the synthesis of derivatives with high yields, short reaction times, and low operating temperatures.

Conclusion

Research on the synthesis of pyrazoles derivatives, prized for their medicinal potential, has spurred interest among scientists. Our focus lies in innovating a robust, reusable catalyst for facilitating the one-pot two-component and three-component synthesis of these compounds. Our novel catalyst, derived from copper iodide immobilized on magnetic graphene oxide modified with the ligand N'1,N'3-bis(2-aminobenzoyl)benzene-1,3-disulfonohydrazide (ABDSH), underwent rigorous structural validation via various analyses including FTIR, EDX, MAPPING, TGA/DSC, VSM, and FESEM. Leveraging the chelated copper interaction with raw material groups, GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI demonstrates superior performance, expediting product synthesis. Furthermore, the magnetic properties of nanocomposite facilitate effortless catalyst separation and recycling from reaction mixtures, with iron metal aiding both catalyst retrieval and reaction progression. Control experiments employing 50 mg of GO@Fe3O4@PTMS@ABDSH@CuI, without solvent at 55 °C and 70 °C, obtained products in high yields (Tables 3 and 5). Notably, the catalyst exhibited sustained efficacy over four recycling cycles.

Data availability

Data is provided within the supplementary information files.

References

Eidi, E., Kassaee, M. Z., Nasresfahani, Z. & Cummings, P. T. Synthesis of quinazolines over recyclable Fe3O4@SiO2-PrNH2-Fe3+ nanoparticles: A green, efficient, and solvent-free protocol. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 32, 1–9 (2018).

Franco, R. T. et al. Green synthesis of iron oxides and phosphates via thermal treatment of iron polyphenols synthesized by a camellia sinensis extract. Inorg. Chem. 60, 5734–5746 (2021).

Verma, C. et al. Principles and theories of green chemistry for corrosion science and engineering: Design and application. Green Chem. 26, 4270–4357 (2024).

Momeni, S. & Ghorbani-Vaghei, R. A facile one-pot synthesis of tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyrans and 2-amino-4H-chromenes under green conditions. RSC Adv. 14, 21608–21622 (2024).

Soliman, A. M., Mohamed, S. K., El-Remaily, M. A. E. A. A. A. & Abdel-Ghany, H. Synthesis of pyrimidine, dihydropyrimidinone, and dihydroimidazole derivatives under free solvent conditions and their antibacterial evaluation. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 51, 1202–1209 (2014).

Farooq Khan, M. et al. Eco-friendly elimination of organic pollutants from water using graphene oxide assimilated magnetic nanoparticles adsorbent. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 139, 109422 (2022).

El Aleem Ali El-Remaily, M. A., Abu-Dief, A. M. & El-Khatib, R. M. A robust synthesis and characterization of superparamagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient and reusable catalyst for green synthesis of some heterocyclic rings. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 30, 1022–1029 (2016).

Kamel, M. S. et al. Green synthesis design, spectroscopic characterizations, and biological activities of novel pyrrole derivatives: An application to evaluate their toxic effect on cotton aphids. ChemistrySelect 7, e202203191 (2022).

Azizi, S., Shadjou, N. & Hasanzadeh, M. KCC-1 aminopropyl-functionalized supported on iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles as a novel magnetic nanocatalyst for the green and efficient synthesis of sulfonamide derivatives. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5321 (2020).

Jiao, T. et al. Facile and scalable preparation of graphene oxide-based magnetic hybrids for fast and highly efficient removal of organic dyes. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–10 (2015).

Mirheidari, M. & Safaei-Ghomi, J. Design, synthesis, and catalytic performance of modified graphene oxide based on a cobalt complex as a heterogenous catalyst for the preparation of aminonaphthoquinone derivatives. RSC Adv. 11, 17108–17115 (2021).

Shahbazi-Alavi, H., Kareem Abbas, A. & Safaei-Ghomi, J. Synthesis of thiazoles catalyzed by dichlorotriazine attached to graphene oxide. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 53, 426–430 (2021).

Momeni, S. & Ghorbani-Vaghei, R. Green synthesis of quinazoline derivatives using a novel recyclable nano-catalyst of magnetic modified graphene oxide supported with copper. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–17 (2023).

Qin, H., Wu, X., Xue, X. & Liu, H. Light actuated swarming and breathing-like motion of graphene oxide colloidal particles. Commun. Chem. 1, 1–11 (2018).

Dehghan-Manshadi, M. S., Kareem Abbas, A., Esfandiari, M., Shahbazi-Alavi, H. & Safaei-Ghomi, J. CeO2/CuO@GQDs@NH2 nanocomposite as a reusable catalyst for the preparation of bis-pyrazoles. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 53, 254–261 (2021).

Bi, C. et al. Facile synthesis of hydrophilic magnetic graphene nanocomposites via dopamine self-polymerization and Michael addition for selective enrichment of N-linked glycopeptides. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–10 (2020).

Ghasemi, Z., Amale, A. H., Azizi, S., Valizadeh, S. & Soleymani, J. Magnetic sulfonated polysaccharides as efficient catalysts for synthesis of isoxazole-5-one derivatives possessing a substituted pyrrole ring, as anti-cancer agents. RSC Adv. 11, 36958–36964 (2021).

Azizi, S., Soleymani, J. & Hasanzadeh, M. Iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles supported on amino propyl-functionalized KCC-1 as robust recyclable catalyst for one pot and green synthesis of tetrahydrodipyrazolopyridines and cytotoxicity evaluation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5440 (2020).

Azizi, S., Shadjou, N. & Soleymani, J. CuI/Fe3O4 NPs@Biimidazole IL-KCC-1 as a leach proof nanocatalyst for the synthesis of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines in aqueous medium. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 35, e6031 (2021).

Abd, M. A. E. A. A. & Hamad, H. A. Synthesis and characterization of highly stable superparamagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles as a catalyst for novel synthesis of thiazolo[4,5-b]quinolin-9-one derivatives in aqueous medium. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 404–405, 148–155 (2015).

Azizi, S. & Shadjou, N. Iron oxide (Fe3O4) magnetic nanoparticles supported on wrinkled fibrous nanosilica (WFNS) functionalized by biimidazole ionic liquid as an effective and reusable heterogeneous magnetic nanocatalyst for the efficient synthesis of N-sulfonylamidines. Heliyon 7, e05915 (2021).

Dehghan, M. et al. Novel approach to synthesizing polymer-functionalized Fe3O4/SiO2–NH2 via an ultrasound-assisted method for catalytic selective oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes and ketones in a DMSO/water mixture. RSC Adv. 5, 92335–92343 (2015).

Liu, R., Zhu, X. & Chen, B. A new insight of graphene oxide-Fe(III) complex photochemical behaviors under visible light irradiation. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–11 (2017).

Vanukuri, O. R. et al. A convenient approach for the synthesis of 4,4’-((substituted phenyl)methylene)bis(3-methyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol) and their antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Synth. Commun. 53, 1886–1901 (2023).

Hosseine, M., Naghib, S. M. & Khodadadi, A. Label-free electrochemical biosensor based on green-synthesized reduced graphene oxide/Fe3O4/nafion/polyaniline for ultrasensitive detection of SKBR3 cell line of HER2 breast cancer biomarker. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–18 (2024).

Dadvar, F. & Elhamifar, D. Magnetic silica/graphene oxide nanocomposite supported ionic liquid–manganese complex as a powerful catalyst for the synthesis of tetrahydrobenzopyrans. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–13 (2023).

Hojati, S. F., Amiri, A. & Ghavidel, S. Copolymer-coated magnetic graphene oxide: A reusable catalyst for the preparation of 2,4,6-Triaryl pyridines via four-component reaction. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 44, 3146–3160 (2024).

Peng, L. et al. Magnetic graphene oxide supported tin oxide (SnO) nanocomposite as a heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production from soybean oil. Renew. Energy 224, 120050 (2024).

Babapoor, A., Asgharzadeh, R. & Pourshahi, M. Cu(I) schiff base complex stabilized on magnetic graphene oxide as a recoverable heterogeneous catalyst for N-arylation of amines under mild conditions and with high efficiency. Chem. Africa 7, 5291–5303 (2024).

Ali El-Remaily, M. A. E. A. A., Hamad, H. A., Soliman, A. M. M. & Elhady, O. M. Boosting the catalytic performance of manganese (III)-porphyrin complex MnTSPP for facile one-pot green synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives under mild conditions. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 35, e6238 (2021).

El-Remaily, M. A. E. A. A. A. et al. Efficient and recoverable novel pyranothiazol Pd (II), Cu (II) and Fe(III) catalysts in simple synthesis of polyfunctionalized pyrroles: Under mild conditions using ultrasonic irradiation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 35, e6370 (2021).

Gong, S. S. et al. Multicomponent reaction-based discovery of pyrimido[2,1-b][1,3]benzothiazole (PBT) as a novel core for full-color-tunable AIEgens. J. Mater. Chem. C. 9, 10029–10036 (2021).

Kamalzare, M., Ahghari, M. R., Bayat, M. & Maleki, A. Fe3O4@chitosan-tannic acid bionanocomposite as a novel nanocatalyst for the synthesis of pyranopyrazoles. Sci. Repo. 11, 1–10 (2021).

Momeni, S. & Ghorbani-Vaghei, R. Green and efficient synthesis of 5-amino-1H-pyrazole-5-carbonitriles utilizing novel modified LDH. Nanoscale Adv. 6, 6290–6302 (2024).

Rasooll, M. M., Sepehrmansourie, H., Zarei, M., Zolfigol, M. A. & Rostamnia, S. Phosphonic acid tagged carbon quantum dots encapsulated in SBA-15 as a novel catalyst for the preparation of N-heterocycles with pyrazolo, barbituric acid and indole moieties. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–14 (2022).

Ladani, N. et al. Ranjan Microwave assisted synthesis of novel Hantzsch 1, 4-dihydropyridines, acridine-1, 8-diones and polyhydroquinolines bearing the tetrazolo quinoline moiety and their antimicrobial activity assess. Chin. Chem. Lett. 22, 1407–1410 (2011).

Ghanbarpour, A., Ghorbani-Choghamarani, A., Aghavandi, H. & Jafari, A. ZnFe2O4@SiO2@L-lysine@SO3H: Preparation, characterization, and its catalytic applications in the oxidation of sulfides and synthesis of Bis(pyrazolyl)methanes. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–20 (2024).

El-Remaily, M. A. E. A. A. Synthesis of pyranopyrazoles using magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles as efficient and reusable catalyst. Tetrahedron 70, 2971–2975 (2014).

Talebian, M. R., Ebrahimi, S. N., Azizi, S. & Bazgir, A. Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxic evaluation of pyrazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline-triazole conjugates. J. Mol. Struct. 1322, 140625 (2025).

MiraniNezhad, S. et al. Poly(aniline-co-melamine)@MnFe2O4 nanocatalyst for the synthesis of 4,4’-(arylmethylene) bis (1H-pyrazole-5-ol) derivatives, and 1,4- dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazoles and evaluation of their antioxidant, and anticancer activities. Front. Chem. 10, 1046120–1046120 (2022).

Danne, A. B., Deshpande, M. V., Sangshetti, J. N., Khedkar, V. M. & Shingate, B. B. New 1,2,3-Triazole-appended bis-pyrazoles: Synthesis, bioevaluation, and molecular docking. ACS Omega 6, 24879–24890 (2021).

Moosavi-Zare, A. R. et al. Design, characterization and application of new ionic liquid 1-sulfopyridinium chloride as an efficient catalyst for tandem Knoevenagel-Michael reaction of 3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-one with aldehydes. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 467, 61–68 (2013).

Soliman, A. M., Sultan, A. A., El Remaily, M. A. A. & Abdel-Ghany, H. Synthesis of some novel fused azole derivatives. Synth. Commun. 42, 2748–2762 (2012).

Elyasi, Z., Ghomi, J. S., Najafi, G. R. & Sharif, M. A. Fabrication of uniform Pd nanoparticles immobilized on crosslinked ionic chitosan support as a super-active catalyst toward regioselective synthesis of pyrazole-fused heterocycles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 253, 126589 (2023).

Khaligh, N. G., Mihankhah, T., Gorjian, H. & Johan, M. R. Greener and facile synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol)s through a conventional heating procedure. Synth. Commun. 50, 3276–3286 (2020).

Kuarm, B. S. & Rajitha, B. Xanthan sulfuric acid: An efficient, biosupported, and recyclable solid acid catalyst for the synthesis of 4,4-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols). Synth. Commun. 42, 2382–2387 (2012).

Nikoorazm, M., Mohammadi, M. & Khanmoradi, M. Zirconium@guanine@MCM-41 nanoparticles: An efficient heterogeneous mesoporous nanocatalyst for one-pot, multi-component tandem Knoevenagel condensation–Michael addition–cyclization reactions. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5704 (2020).

Gupta, A. et al. Visible light-promoted green and sustainable approach for one-pot synthesis of 4,4’-(Arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols), in vitro anticancer activity, and molecular docking with covid-19 Mpro. ACS Omega 7, 34583–34598 (2022).

Zhou, Z. & Zhang, Y. An eco-friendly one-pot synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ols) using [Et3NH][HSO4] as a recyclable catalyst. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 60, 2992–2996 (2015).

Hasaninejad, A., Shekouhy, M., Zare, A., Hoseini Ghattali, S. M. S. & Golzar, N. PEG-SO3H as a new, highly efficient and homogeneous polymeric catalyst for the synthesis of Bis(indolyl)methanes and 4, 4’-(Arylmethylene)- bis(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1hpyrazol-5-ol)s in water. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 8, 411–423 (2011).

Momeni, S. & Ghorbani-Vaghei, R. Facile synthesis of novel acidic modified magnetic graphene oxide and its application in the green synthesis of pyrimido[4,5-b]quinolines. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–17 (2024).

Momeni, S. & Ghorbani-Vaghei, R. Synthesis, properties, and application of the new nanocatalyst of double layer hydroxides in the one-pot multicomponent synthesis of 2-amino-3-cyanopyridine derivatives. Sci. Rep. 13, 1627 (2023).

Esmaeili, Y., Bidram, E., Zarrabi, A., Amini, A. & Cheng, C. Graphene oxide and its derivatives as promising In-vitro bio-imaging platforms. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–13 (2020).

Ossonon, B. D. & Bélanger, D. Synthesis and characterization of sulfophenyl-functionalized reduced graphene oxide sheets. RSC Adv. 7, 27224–27234 (2017).

Thu, N. T. A. et al. Electrochemical determination of paracetamol using Fe3O4/reduced graphene-oxide-based electrode. J. Nanomater. 2018, 7619419 (2018).

Thy, L. T. M. et al. Fabrication and adsorption properties of magnetic graphene oxide nanocomposites for removal of arsenic (V) from water. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 38, 240–253 (2020).

Patil, P. G., Sehlangia, S. & More, D. H. Chitosan-SO3H (CTSA) an efficient and biodegradable polymeric catalyst for the synthesis of 4,4′-(arylmethylene)bis(1H-pyrazol-5-ol) and α-amidoalkyl-β-naphthol’s. Synth. Commun. 50, 1696–1711 (2020).

Purohit, V. B., Karad, S. C., Patel, K. H. & Raval, D. K. Palladium N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed expected and unexpected C-C and C–N functionalization reactions of 1-aryl-3-methyl-1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-ones. RSC Adv. 6, 111139–111143 (2016).

Mansouri, N., Baghery, S. & Zolfigol, M. A. A new approach for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrano[c ]bifunctional nanostructured ionic liquid catalyst. Nanochem Res 3, 170–177 (2018).

Filian, H., Ghorbani-Choghamarani, A. & Tahanpesar, E. Ni-guanidine@MCM-41 NPs: A new catalyst for the synthesis of 4,4ʹ-(arylmethylene)-bis-(3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ols) and symmetric di-aryl sulfides. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 12, 2673–2681 (2019).

Ghanbarpour, A. et al. Synthesis of 4,4’-(Aryl Methylene)Bis(3-Methyl-1H-Pyrazol-5-ol) derivatives and Pyrano[2, 3-c] Pyrazole derivatives using an engineered copper-based nano-magnetic catalyst (Fe3O4@SiO2/Si(OEt)(CH2)3NH/CC/EDA/Cu(OAc)2). Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 43, 3192–3215 (2022).

Baghernejad, M. & Niknam, K. Synthesis of 4, 4’-(arylmethylene) bis (1H-pyrazol-5-ols) using silica-bonded ionic liquid as recyclable catalyst. International J. Chem. 4, 52 (2012).

Fatahpour, M. et al. Aspirin: An efficient catalyst for synthesis of bis (pyrazol-5-ols), dihydropyranopyrazoles and spiropyranopyrazoles in an environmentally benign manner. Iran. Chem. Soc. 14, 1945–1956 (2017).

Eskandari, K., Karami, B., Khodabakhshi, S. & Farahi, M. A highly efficient tandem knoevenagel/michael reaction using Mohr’s salt hexahydrate as a green and powerful catalyst: Selective synthesis of benzylpyrazolocoumarins on water. JCCS. 62, 473–478 (2015).

Eskandari, K., Karami, B., Khodabakhshi, S. & Farahi, M. A highly efficient tandem knoevenagel/michael reaction using Mohr’s salt hexahydrate as a green and powerful catalyst: Selective synthesis of benzylpyrazolocoumarins on water. J. Chinese Chem. Soc. 62, 473–478 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Bu-Ali Sina University, Center of Excellence Developmental of Environmentally Friendly Methods for Chemical Synthesis (CEDEFMCS) and for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.GH and S.M. conceived the experiments and provided experimental instructions, S.M. performed the experiments, analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Momeni, S., Ghorbani-Vaghei, R. Novel modified magnetic graphene oxide as an efficient and green catalyst for one-pot synthesis of pyrazoles. Sci Rep 15, 14263 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97884-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97884-6