Abstract

This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of combining high-dose-rate brachytherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and docetaxel as second-line treatment for advanced NSCLC, given the poor prognosis after first-line therapy. We conducted a single-center, retrospective, propensity score-matched study comparing HDR brachytherapy plus ICIs and docetaxel (study group) versus ICIs plus docetaxel (control group) in patients with advanced NSCLC who progressed after prior treatment without known driver gene mutations or uninvestigated mutation status. After propensity score matching, 21 patients were included in each group. The study group had a higher ORR (42.9% vs. 28.6%). Median OS was 18.6 months for the study group and 12.8 months for the control group (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.20–0.85, P = 0.042). Median PFS was 8.6 vs. 5.6 months (HR 0.29, 95% CI 0.15–0.55, P < 0.001). The DCR was higher in the study group (71.4% vs. 61.9%). Treatment-related AEs were manageable, with no significant increase in grade 3/4 toxicities in the study group. Results suggest that combining high-dose rate brachytherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and docetaxel may improve survival and response rates in advanced NSCLC after first-line therapy. Prospective randomized trials are necessary to confirm these findings and validate the strategy’s effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Lung cancer remains the most lethal malignancy worldwide, with NSCLC accounting for approximately 85% of all lung cancer diagnoses1. In recent years, significant advances in targeted therapies and immunotherapy have changed the outlook of NSCLC treatment and improved the prognosis of patients with advanced NSCLC. Related diagnostic and therapeutic targets have also been proposed one after another2,3. However, despite these advances, the overall prognosis for patients with advanced NSCLC remains dismal, especially those experiencing disease progression after initial treatment4,5,6. Platinum-based docetaxel has long been considered the standard of care for second-line treatment in advanced NSCLC, but its efficacy is limited, with a median OS that extended only to 7.5 months compared to 4.6 months for supportive care alone7. These compelling statistics highlight the urgent need to develop new and more effective second-line treatments to improve the quality of life for patients with advanced NSCLC.

With the clinical use of ICIs, drugs that activate the body’s immune system to target and destroy cancer cells, the treatment and prognosis of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer has improved8,9. However, not all patients respond to ICIs, and the combination of ICIs and docetaxel has been explored as a method to to enhance their efficacy10. The KEYNOTE-010 trial demonstrated that in patients with advanced NSCLC and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression of ≥ 1%, compared to doxorubicin alone, pembrolizumab in combination with docetaxel paclitaxel treatment significantly improved OS and PFS11. Similarly, the KEYNOTE-189 trial, which established pembrolizumab plus pemetrexed/platinum as a first-line standard for advanced non-squamous NSCLC regardless of PD-L1 expression, the median OS was 22.0 months with the combination compared to 10.6 months with chemotherapy alone (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.46–0.69)12. These trials emphasize the potential of the combination of ICIs and docetaxel to improve treatment outcomes. Despite these promising results, additional strategies are needed to further improve outcomes, especially for patients with low or negative PD-L 1 expression.

Traditionally, radiotherapy has been used for local control and symptomatic relief of advanced non-small cell lung cancer, but recent evidence suggests that it also has immunomodulatory effects that can enhance the efficacy of ICIs13,14,15. Studies have shown that radiotherapy induces immunogenic cell death, releases tumor-associated antigens, and promotes recruitment and activation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes16,17,18. Clinical trials have also shown that the combination of radiation therapy and ICIs can achieve synergistic anti-tumor effects and improve the survival rate of patients with advanced NSCLC19.

High dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy is radiation therapy that delivers a high dose of radiation directly to the tumor while reducing damage to surrounding normal tissue.HDR brachytherapy is more effective at overcoming radiation resistance and eradicating cancer cells than conventional external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) because it delivers ablative doses to the tumor in a single fraction. While it is difficult to achieve such high doses with EBRT without increasing the toxicity to normal tissue. Also by placing the radiation source directly inside or near the tumor, HDR brachytherapy significantly reduces the dose to normal tissues and minimizes the risk of radiotoxicity (e.g., pneumonia and esophagitis). In addition the shorter total treatment time of a single high-dose fractionated treatment prevents the repopulation of tumor cells that can occur during long-term treatment with conventional fractionated EBRT. And HDR’s radiation source moves with the tumor and is less affected by breathing movements or changes in tumor position, ensuring precise dose delivery.HDR brachytherapy is minimally invasive and can be delivered percutaneously under CT guidance, making it suitable for patients who may not be able to tolerate surgery20. HDR brachytherapy can be readily combined with other therapeutic modalities, such as EBRT, doxorubicin, or immunotherapy for potential synergistic effects.HDR brachytherapy has been shown to be effective in the treatment of locally advanced and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer with excellent local control and survival21,22. However, the role of HDR brachytherapy in combination with ICIs and docetaxel as a second-line treatment for advanced NSCLC has not been previously studied.

In this study, we conducted a single-center, retrospective, propensity score-matched analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of HDR brachytherapy plus ICIs and docetaxel versus ICIs and docetaxel in patients with advanced NSCLC who had progressed after prior therapy. ORR, PFS, OS, DCR, and TRAEs were evaluated. By leveraging the immunomodulatory effects of radiotherapy and the synergistic potential of ICIs and docetaxel, this study aimed to provide a new and effective second-line treatment option for patients with advanced NSCLC who progressed after prior treatment.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a single-center, retrospective, propensity score-matched study comparing the efficacy and safety of HDR brachytherapy with ICIs plus docetaxel versus ICIs plus docetaxel as a second-line treatment for advanced NSCLC. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Second People’s Hospital of Neijiang City(Lun Shen (Yan) 2023 No.10). The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06518018).

Patient selection

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with advanced NSCLC who received second-line treatment at The Second People’s Hospital of Neijiang City between January 2021 and December 2023. Key inclusion criteria were: Key inclusion criteria were: (1) a stage IIIB/IIIC-IV NSCLC confirmed histology; (2) progression after prior treatment (e.g., radiotherapy, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor(VGFR), immunotherapy or docetaxel) ; (3) no known driver gene mutations or rearrangements (e.g., EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF V600E) or uninvestigated mutation status; (4) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–2; and (5) adequate organ function. Main exclusion criteria included: (1) autoimmune disease; (2) ongoing systemic immunosuppressive therapy; and (3) the primary lung tumor is larger than 5 cm, with more than three surrounding lesions.4)uncontrolled brain metastasis or serious complications.

Data collection

Demographic, clinical, and treatment data were extracted from the electronic medical record system, including age, sex, smoking history, histology, PD-L1 expression, treatment details, and clinical outcomes. Propensity score matching was performed to balance baseline characteristics between the two groups.

Treatment

Patients in the study group received concurrent HDR brachytherapy with ICIs and docetaxel, while those in the control group received ICIs plus docetaxel.

HDR brachytherapy

HDR brachytherapy was delivered using a 192Ir source. Under CT guidance, steel brachytherapy needles were percutaneously inserted into the primary lung lesion at 1.0–1.5-cm intervals, following the shortest path through normal tissue to encompass the tumor. To minimize pleural injury, patients were instructed to avoid coughing and deep breathing during needle placement.Post-implantation CT scans were acquired to verify needle positioning before delivering a single 30 Gy dose to the 90% isodose line of the gross tumor volume(GTVL). After treatment, repeat CT imaging was performed to assess applicator displacement, and then the needles were removed. A final CT scan at full exhalation was obtained to exclude post-procedural complications such as pneumothorax or hemorrhage.

Immunotherapy and docetaxel

In the study group, patients received a combined treatment of HDR brachytherapy, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy. The protocol began with a single fraction of HDR brachytherapy. Within 1–3 days post-brachytherapy, patients started concurrent systemic therapy. This consisted of ICIs - either camrelizumab (200 mg), sintilimab (200 mg), pembrolizumab (200 mg), or atezolizumab (1200 mg) - administered alongside docetaxel chemotherapy. Docetaxel was given at a dose of 75 mg/m² on day one of each three-week cycle. The short interval between brachytherapy and the start of systemic therapy was chosen to leverage the potential synergistic effects of radiation and immunotherapy.

In the immunotherapy plus docetaxel group (control group), patients received the same regimen of ICIs and docetaxel.

Follow-up and endpoints

Patients were followed every three months after treatment initiation. The primary endpoint was ORR. Secondary endpoints included PFS, OS, DCR, and safety.

Evaluation of treatment response and toxicity

Tumor response was assessed by CT or MRI every three months during follow-up. Toxicities were graded according to CTCAE v5.0.

Propensity score matching

To minimize potential selection bias and confounding factors in this non-randomized study, propensity score matching was employed to create comparable groups for analysis. The propensity score was defined as the probability of receiving HDR brachytherapy in addition to immunotherapy and docetaxel, conditional on observed baseline characteristics.

Logistic regression models were used to estimate propensity scores for each patient, including the following covariates: age (continuous), sex (male vs. female), smoking history (never vs. former/current smoker), histology (squamous vs. non-squamous), presence of brain metastases (yes vs. no), and number of metastatic sites (1 vs. ≥2). These variables were selected based on their potential association with treatment tasks and clinical outcomes.

Patients in the HDR brachytherapy plus immunotherapy and docetaxel group were matched 1:1 to patients in the immunotherapy plus docetaxel group using a nearest-neighbor algorithm where the caliper width was equal to 0.2 times the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score. This caliper width was chosen to achieve a balance between match quality and sample size retention. Matching was performed without substitution, and any patient in the HDR brachytherapy group who could not be matched to a control patient was excluded from the propensity score matching analysis.

The quality of the matching process was assessed by evaluating the balance of baseline characteristics between matched groups using standardized mean differences (SMDs). An SMD < 0.1 for a given covariate was considered an indicator of negligible differences between groups. The distribution of propensity scores before and after matching was also visually examined using density plots to ensure sufficient overlap between groups.

The primary analysis of efficacy and safety outcomes was conducted in the propensity score-matched cohort to minimize the impact of potential confounding factors. Sensitivity analyses were performed in the unmatched cohort to assess the robustness of the findings.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, while continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated using Cox proportional hazards models. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.0.4), with a two-sided P value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Result

Patient characteristics

A total of 42 patients with advanced NSCLC were included in the study, with 21 patients in each group after propensity score matching (Fig. 1). The median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 16 months (range, 5–30 months). The baseline characteristics of the matched cohort are summarized in Table 1. The two groups were well-balanced in terms of age, gender, histology, smoking status, ECOG performance status, presence of brain metastases, previous therapy.

Survival outcomes

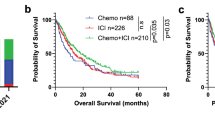

The OS was 18.6 months in the ICIs + Brachytherapy + Docetaxel group and 12.8 months in the ICIs + Docetaxel group (Fig. 2A). The hazard ratio (HR) for death was 0.45 (95% CI, 0.20–0.85; P = 0.042), favoring the ICIs + Brachytherapy + Docetaxel group.

Panel A shows the Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival for the two treatment groups. The median overall survival was 18.6 months in the Brachytherapy + ICIs + Docetaxel group and 12.8 months in the ICIs + Docetaxel group. The hazard ratio for death was 0.45 (95% CI,0.20–0.85; P = 0.042).Panel B shows the Kaplan-Meier estimates of Progression-free Survival for the two treatment groups. The median progression-free survival was 8.6 months in the Brachytherapy + ICIs + Docetaxel group and 5.6 months in the ICIs + Docetaxel group. The hazard ratio for death was 0.29 (95% CI, 0.15–0.55; P < 0.001).

The PFS was 8.6 months in the ICIs + Brachytherapy + Docetaxel group and 5.6 months in the ICIs + Docetaxel group (Fig. 2B). The HR for progression or death was 0.29 (95% CI, 0.15–0.55; P < 0.001), favoring the ICIs + Brachytherapy + Docetaxel group.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses of OS were performed to assess the consistency of treatment effects across prespecified subgroups (Fig. 3). The treatment benefit of ICIs + Brachytherapy + Docetaxel was generally consistent across subgroups defined by age, gender, histology, smoking status, ECOG performance status, presence of brain metastases, previous therapy. HRs for both OS and PFS favored the ICIs + Brachytherapy + Docetaxel group in most subgroups, suggesting the robustness of the observed treatment effect.

Response rates

As shown in Table 2; Figs. 4 and 5, the objective response rate (ORR) was 42.9% (9/21) in the Brachytherapy + ICIs + Docetaxel group and 28.6% (6/21) in the ICIs + Docetaxel group. The difference in ORR between the two groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.521). No complete responses (CR) were observed in either group.

The DCR was 71.4% (15/21) in the Brachytherapy + ICIs + Docetaxel group and 61.9% (13/21) in the ICIs + Docetaxel group. The difference in DCR between the two groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.742).

Progressive disease (PD) was reported in 28.6% (6/21) of patients in the Brachytherapy + ICIs + Docetaxel group and 38.1% (8/21) of patients in the ICIs + Docetaxel group. The difference in PD rates between the two groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.74).

Safety

TRAEs are summarized in Table 3. The most common TRAEs in the ICIs + Brachytherapy + Docetaxel group were fever (23.8%), rash (19.0%),decreased appetite (19.0%), and thrombocytopenia (14.3%). In the ICIs + Docetaxel group, the most common TRAEs were thrombocytopenia (19.0%), fever (19.0%), rash (14.3%), and pneumonitis (14.3%). Grade 3/4 TRAEs were infrequent in both groups. In the ICIs + Brachytherapy + Docetaxel group, grade 3/4 TRAEs included decreased appetite (4.8%), diarrhea (4.8%), fever (4.8%), rash (4.8%), thrombocytopenia (4.8%), and reactive cutaneouscapillary endothelial proliferation (RCCEP) (4.8%). In the ICIs + Docetaxel group, grade 3/4 TRAEs were decreased appetite (4.8%), diarrhea (4.8%), thrombocytopenia (4.8%), pneumonitis (4.8%), and elevated alanine aminotransferase (4.8%). Notably, two cases (9.5%) of pneumothorax were reported in the Brachytherapy + ICIs + Docetaxel group as complications related to the brachytherapy procedure, while no such complication was observed in the ICIs + Docetaxel group. This highlights the need for vigilance and preventive measures during brachytherapy to minimize the risk of procedural complications.

No treatment-related deaths occurred in either group, suggesting that the addition of HDR brachytherapy did not substantially increase the toxicity compared to immunotherapy and docetaxel. Overall, the safety profile was generally manageable in both groups, with a low incidence of severe toxicities.

Discussion

In patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC, various second-line treatment strategies have been explored, especially those combining ICIs with other therapeutic agents, as shown in Table 4. However, the efficacy and safety of integrating HDR brachytherapy with ICIs and docetaxel in this setting have not been well established. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted this single-center, retrospective, propensity score-matched study to investigate the potential benefits of adding HDR brachytherapy to ICIs and docetaxel. Our results demonstrated that the addition of HDR brachytherapy may improve OS, PFS, and ORR compared to ICIs and docetaxel alone. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the efficacy and safety of this combination strategy in patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC.

The clinically significant improvement in outcomes observed after the addition of HDR brachytherapy to ICIs and docetaxel in this study is consistent with a growing body of clinical research that supports the immunomodulatory effects of radiation therapy and its synergistic potential with immunotherapy28,29,30,31. Potentially multiple mechanisms may contribute to enhancing the efficacy of this combination regimen. HDR brachytherapy can induce immunogenic cell death (ICD) in tumor cells, resulting in the release of tumor-associated antigens, danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which promote the maturation of antigen-presenting cells and activation of effector T cells32,33,34,35,36. For instance, Li et al. discovered that irradiation with near-infrared rays can induce a strong endoplasmic reticulum stress response on the cellular surface and the exposure of calreticulin, thereby stimulating the antigen presentation function of dendritic cells (DCs). This process leads to the activation of a series of immune responses including the proliferation of CD8 + T lymphocytes and the secretion of cytotoxic cytokines, ultimately promoting an ICD-related anti-tumor immune response37. Additionally, High-dose radiotherapy results in direct tumor cell death and augments tumor-specific immunity, which enhances tumor control both locally and distantly, and administration of anti-PD-L1 enhanced the efficacy of radiotherapy through a cytotoxic T cell-dependent mechanism38. Moreover, Radiotherapy can stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory mediators and chemokines from tumor cells and stromal cells, including CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, and CXCL16. This facilitates the immune infiltration of dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, and T lymphocytes, thereby increasing cellular abundance and effectively activating the Tumor Immune Microenvironment (TIME)39.

HDR brachytherapy may exert a more effective immunostimulatory effect than conventional fractionated radiation therapy. Recent studies have found that radiotherapy enhances the host immune system’s recognition and killing of tumor cells by upregulating the expression of MHC class I molecules on the surface of tumor cells. This upregulation facilitates the infiltration of CD8 + and CD4 + T lymphocytes and improves their antigen recognition capabilities against tumor cells40,41. Lin et al. demonstrates that radiotherapy promotes the immune infiltration of CD8 + and CD4 + T lymphocytes and enhances their antigen recognition of tumor cells by inducing the production of small extracellular vesicles from tumor cells. This mechanism serves to enhance the anti-tumor immune response42. The spatial cooperation between local radiotherapy and systemic immunotherapy may also contribute to the improved outcomes. The immune responses elicited by local radiotherapy can lead to “abscopal effects” in non-irradiated distant tumor sites43, which may be further potentiated when combined with ICIs, amplifying the systemic anti-tumor immune responses.

The survival benefits observed in our study are particularly noteworthy given the limited treatment options and poor prognosis for patients with advanced NSCLC who progress after first-line therapy. In the KEYNOTE-010 trial, which established pembrolizumab as a standard second-line treatment for advanced NSCLC with PD-L1 expression ≥ 1%, the median OS was 10.4 months with pembrolizumab compared to 8.5 months with docetaxel (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.58–0.88)11. Zhang et al. reported the results of a single-arm phase II clinical trial investigating the efficacy of sintilimab in combination with docetaxel for the treatment of advanced NSCLC. In 30 patients receiving second-line therapy, the ORR reached 36.7%, with a median PFS of 5 months and a median OS of 13.4 months44. These findings preliminarily demonstrate the favorable efficacy of combining PD-1 inhibitors with docetaxel as a second-line treatment for NSCLC, which is consistent with the results of our study. In our study, the median OS was 18.6 months in the HDR brachytherapy plus ICIs and docetaxel group, suggesting a potential improvement in survival outcomes with this combination approach.

Regarding the dose selection for HDR brachytherapy, this study used a single fraction of 30 Gy, which is higher than conventional external beam radiotherapy doses but within the commonly used and safe range for HDR brachytherapy45. Although this dose was shown in our study to be potentially effective with a concomitant safety profile, the sample size of this study was too small and the optimal dose of HDR brachytherapy in combination with ICIs and docetaxel for the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer remains to be determined. In addition the choice of radiation dose and segmentation can significantly affect the immunomodulatory effects of radiation therapy. Several studies have suggested that high-dose radiation (e.g., a single division of 15–20 Gy or a low-division regimen with a dose ≥ 8 Gy per division) may be more effective in inducing ICD and stimulating antitumor immunity compared with conventional division46,47. However, how to balance the efficacy and potential toxicity is something that will require careful clinical deliberation.

In addition, choosing the appropriate radiation dose and the timing of HDR radiation therapy application can be particularly important. In this study, HDR radiation therapy was administered prior to the use of ICIs and docetaxel, while systemic therapy was initiated within 1–3 days after radiation therapy. This sequencing allowed for initial stimulation of antitumor immunity by HDR radiation therapy, followed by further amplification of the effect by the use of ICIs and docetaxel. However, alternative sequencing strategies, such as concurrent radiation therapy with ICIs or docetaxel, have also shown promise in preclinical and clinical studies. In addition, tumor characteristics and the immune microenvironment have a significant impact on treatment response. Tumors exhibiting high PD-L1 expression, high tumor mutational load, or favorable immunogenetic markers are more likely to respond to immunotherapy combinations48,49. Incorporating these biomarkers into future clinical trials may help to identify subgroups of patients most likely to benefit from the combination of HDR brachytherapy and immunotherapy, allowing for a personalized treatment approach. However, due to the limited sample size of the subgroup analysis, we were unable to obtain statistically significant differences.

In the present era of remarkable progress in immunotherapy, which has become one of the core modalities in second-line treatment, While there is currently no unified understanding regarding re-irradiation for advanced NSCLC, with a lack of consensus on the optimal dose and maximum cumulative dose for critical organs50.The primary challenges associated with re-irradiation include the potential for severe toxicity and treatment-related mortality, particularly when exceeding the maximum tolerated dose of critical organs. Additionally, the radiobiological characteristics of recurrent tumors remain unclear, which may influence radiosensitivity. Furthermore, the suitability and sequence of combining re-irradiation with systemic therapies, such as immunotherapy or docetaxel, have not been definitively established51. However, based on current exploratory studies52,48,54, high-dose radiotherapy for local treatment as a re-irradiation approach may play a role in controlling lesions, while offering the advantages of precision, lower risk of complications, and higher tolerability, potentially making it a viable option for re-irradiation in NSCLC.

For patients who have previously received immunotherapy and subsequently experienced disease progression, therapeutic interventions may be effectiveness. This is likely attributed to the acquired resistance within the tumor microenvironment55. For these patients, tailored treatment plans can be designed, integrating a combination of docetaxel, immunotherapy, and radiotherapy not previously utilized56. In this study, the benefits observed in patients with prior immunotherapy exposure were limited. Due to the restricted sample size, we cannot ascertain whether these patients would benefit from the addition of HDR brachytherapy. However, given the substantial palliative impact of HDR brachytherapy on local lesions, we anticipate that further research will validate the efficacy of this integrated treatment approach.

The safety profile of HDR brachytherapy plus ICIs and docetaxel in our study was generally consistent with the known toxicities of each individual modality, with no new safety signals identified. The most common adverse events were rash, fever, and thrombocytopenia, which were manageable with appropriate supportive care. Importantly, the addition of HDR brachytherapy did not appear to significantly increase the incidence of severe (grade 3/4) toxicities compared to ICIs and docetaxel. While two cases of pneumothorax were observed in the HDR brachytherapy group, this complication can be effectively managed and minimized through careful patient selection, meticulous procedural technique, and close monitoring of patients during and after the brachytherapy session.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, this is a retrospective study and the relatively small sample size may have introduced potential biases and limited the power to detect differences in some outcomes. Although the use of propensity score matching helped to minimize confounding and ensure balanced comparisons between the treatment groups. Second, We only performed statistical analysis on the primary lesions in the lungs. We did not collect the imaging data for the metastatic lesions that some patients may have had. This limits the impact of possible distant effects that radiotherapy may have. Third, the lack of data on PD-L1 expression for some patients may have influenced the treatment outcomes, although the proportion of patients with unknown PD-L1 status was balanced between the groups after matching. Fourth, the limited number of patients with prior immunotherapy and radiotherapy in this study precludes an effective exploration of their impact on treatment efficacy and outcomes. Fifthly, the study’s focus on the primary lesion limits detailed analysis of distant metastasis response. Future research should incorporate comprehensive RECIST assessments of distant lesions and explore biomarkers to better understand the systemic impact of this combined modality approach. Finally, longer follow-up is needed to assess the durability of the observed treatment effects and to monitor for potential late toxicities.

Conclusion

In patients with advanced NSCLC who progressed after first-line treatment, the addition of HDR brachytherapy to ICIs and docetaxel significantly prolonged overall survival and progression-free survival, improved objective response rate, and demonstrated a manageable safety profile compared to ICIs and docetaxel alone. These findings suggest that this novel combination approach may provide a promising new therapeutic option for patients with advanced NSCLC in the second-line treatment. Prospective, randomized trials are needed to confirm these results and establish the role of HDR brachytherapy in combination with ICIs and docetaxel in the future.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Xu, S. et al. Exploring FNDC4 as a biomarker for prognosis and immunotherapy response in lung adenocarcinoma. Asian J. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2024.09.054 (2024).

Xu, S. et al. The role of LMNB2 as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in lung adenocarcinoma. Asian J. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2024.08.056 (2024).

Chen, R. et al. Emerging therapeutic agents for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 13, 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00881-7 (2020).

Araghi, M. et al. Recent advances in non-small cell lung cancer targeted therapy; an update review. Cancer Cell. Int. 23, 162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-023-02990-y (2023).

Xiao, Y. et al. Recent progress in targeted therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1125547. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1125547 (2023).

Shepherd, F. A. et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 18, 2095–2103. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2000.18.10.2095 (2000).

Zeng, T. et al. Strategies for improving the performance of prediction models for response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy in cancer. BMC Res. Notes. 17, 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-024-06760-5 (2024).

Pardoll, D. M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 12, 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3239 (2012).

Gandhi, L. et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 378, 2078–2092. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1801005 (2018).

Herbst, R. S. et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387, 1540–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01281-7 (2016).

Garassino, M. C. et al. Patient-reported outcomes following pembrolizumab or placebo plus pemetrexed and platinum in patients with previously untreated, metastatic, non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-189): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21, 387–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(19)30801-0 (2020).

Weichselbaum, R. R. et al. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: A beneficial liaison? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14, 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.211 (2017).

Theelen, W. et al. Effect of pembrolizumab after stereotactic body radiotherapy vs pembrolizumab alone on tumor response in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Results of the PEMBRO-RT phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 5, 1276–1282. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1478 (2019).

Spaas, M. et al. Checkpoint inhibitors in combination with stereotactic body radiotherapy in patients with advanced solid tumors: The CHEERS phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 9, 1205–1213. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.2132 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. CD39 Inhibition and VISTA blockade may overcome radiotherapy resistance by targeting exhausted CD8 + T cells and immunosuppressive myeloid cells. Cell. Rep. Med. 4, 101151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101151 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Immune modulatory roles of radioimmunotherapy: Biological principles and clinical prospects. Front. Immunol. 15, 1357101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1357101 (2024).

Kong, Y. et al. Optimizing the treatment schedule of radiotherapy combined with Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in metastatic cancers. Front. Oncol. 11, 638873. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.638873 (2021).

Shaverdian, N. et al. Previous radiotherapy and the clinical activity and toxicity of pembrolizumab in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: A secondary analysis of the KEYNOTE-001 phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18, 895–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30380-7 (2017).

Skowronek, J. Brachytherapy in the treatment of lung cancer—a valuable solution. J. Contemp. Brachytherapy. 7, 297–311. https://doi.org/10.5114/jcb.2015.54038 (2015).

Nguyen, Q. N. et al. Single-fraction stereotactic vs conventional multifraction radiotherapy for pain relief in patients with predominantly nonspine bone metastases: A randomized phase 2 trial. JAMA Oncol. 5, 872–878. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0192 (2019).

Xiang, L. et al. Effect of 3-dimensional interstitial high-dose-rate brachytherapy with regional metastatic lymph node intensity-modulated radiation therapy in locally advanced peripheral non-small cell lung cancer: 5-Year follow-up of a phase 2 clinical trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 115, 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2022.07.028 (2023).

Taniguchi, Y. et al. A randomized comparison of nivolumab versus nivolumab + Docetaxel for previously treated advanced or recurrent ICI-Naïve non-small cell lung cancer: TORG1630. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 4402–4409. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-22-1687 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Nivolumab combined docetaxel versus nivolumab in patients with previously treated nonsmall cell lung cancer: A phase 2 study. Anticancer Drugs. 35, 412–417. https://doi.org/10.1097/cad.0000000000001569 (2024).

Arrieta, O. et al. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab plus docetaxel vs docetaxel alone in patients with previously treated advanced Non-Small cell lung cancer: The PROLUNG phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 6, 856–864. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0409 (2020).

Zhang, F. et al. Anti-PD-1 therapy plus chemotherapy and/or bevacizumab as second line or later treatment for patients with advanced Non-Small cell lung cancer. J. Cancer. 11, 741–749. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.37966 (2020).

Huang, H. et al. Immunotherapy combined with rh-endostatin improved clinical outcomes over immunotherapy plus chemotherapy for second-line treatment of advanced NSCLC. Front. Oncol. 13, 1137224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1137224 (2023).

Ngwa, W. et al. Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 18, 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2018.6 (2018).

Vafaei, S. et al. Combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs); a new frontier. Cancer Cell. Int. 22, 2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-021-02407-8 (2022).

Yu, S. et al. Effective combinations of immunotherapy and radiotherapy for cancer treatment. Front. Oncol. 12, 809304. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.809304 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy: The dawn of cancer treatment. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 258. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01102-y (2022).

Bao, X. et al. Targeting purinergic pathway to enhance radiotherapy-induced Immunogenic cancer cell death. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 41, 222. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-022-02430-1 (2022).

Rodriguez-Ruiz, M. E. et al. Intratumoral BO-112 in combination with radiotherapy synergizes to achieve CD8 T-cell-mediated local tumor control. J. Immunother Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2022-005011 (2023).

Liang, J. et al. PITPNC1 suppress CD8(+) T cell immune function and promote radioresistance in rectal cancer by modulating FASN/CD155. J. Transl Med. 22, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-04931-3 (2024).

Formenti, S. C. et al. Systemic effects of local radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 10, 718–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70082-8 (2009).

Liu, X. et al. Targeting T cell exhaustion: Emerging strategies in non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Immunol. 15, 1507501. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1507501 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Targeting photodynamic and photothermal therapy to the endoplasmic reticulum enhances Immunogenic cancer cell death. Nat. Commun. 10, 3349. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11269-8 (2019).

Deng, L. et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 687–695. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci67313 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. The reciprocity between radiotherapy and cancer immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 1709–1717. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-2581 (2019).

Jin, W. J. et al. ATM Inhibition augments type I interferon response and antitumor T-cell immunity when combined with radiation therapy in murine tumor models. J. Immunother Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2023-007474 (2023).

Zeng, H. et al. Radiotherapy activates autophagy to increase CD8(+) T cell infiltration by modulating major histocompatibility complex class-I expression in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Int. Med. Res. 47, 3818–3830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060519855595 (2019).

Lin, W. et al. Radiation-induced small extracellular vesicles as carriages promote tumor antigen release and trigger antitumor immunity. Theranostics 10, 4871–4884. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.43539 (2020).

Twyman-Saint Victor, C. et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature 520, 373–377. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14292 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Sintilimab plus docetaxel as second-line therapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer without targetable mutations: A phase II efficacy and biomarker study. BMC Cancer. 22, 952. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-10045-0 (2022).

Qiu, B. et al. Brachytherapy for lung cancer. Brachytherapy 20, 454–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brachy.2020.11.009 (2021).

Golden, E. B. et al. Local radiotherapy and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to generate abscopal responses in patients with metastatic solid tumours: A proof-of-principle trial. Lancet Oncol. 16, 795–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00054-6 (2015).

Tateishi, Y. et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy with a high maximum dose improves local control, cancer-Specific death, and overall survival in peripheral early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 111, 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.04.014 (2021).

Lau, J. et al. Tumour and host cell PD-L1 is required to mediate suppression of anti-tumour immunity in mice. Nat. Commun. 8, 14572. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14572 (2017).

Hendriks, L. E. et al. Clinical utility of tumor mutational burden in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with immunotherapy. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 7, 647–660. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr.2018.09.22 (2018).

Sonoda, D. et al. Prognosis of patients with recurrent nonsmall cell lung cancer who received the best supportive care alone. Curr. Probl. Surg. 61, 101429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpsurg.2023.101429 (2024).

Rulach, R. et al. Re-irradiation for locally recurrent lung cancer: Evidence, risks and benefits. Clin. Oncol. (R Coll. Radiol). 30, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2017.11.003 (2018).

Grambozov, B. et al. Re-Irradiation for locally recurrent lung cancer: A single center retrospective analysis. Curr. Oncol. 28, 1835–1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28030170 (2021).

Grambozov, B. et al. High dose thoracic Re-Irradiation and Chemo-Immunotherapy for centrally recurrent NSCLC. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14030573 (2022).

Horvath, L. et al. Overcoming immunotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) - novel approaches and future outlook. Mol. Cancer. 19, 141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-020-01260-z (2020).

Billan, S. et al. Treatment after progression in the era of immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 21, e463–e476. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30328-4 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of DeepL in improving the grammar, word choice, and writing of this manuscript. The use of DeepL did not affect the authenticity or integrity of the original data presented in this study.

Funding

This study as suwpported by a 2023 research project from the Sichuan Medical Association (Project Number: S23092). The 2024 research project from the Technology Department of Sichuan Provincial Science and Central Guidance Local Exploration Fund Project(24ZYZYTS0262).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception: R. C. Design of the work: Y. L. and X. Y. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: R. C., Y. J. and X. Y. Writing: original draft: X. M. Writing—revising & editing: R. C. and Y. L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of The Second People’s Hospital of Neijiang in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual patients included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, R., Su, H., Jiang, Y. et al. Propensity score analysis of high-dose rate brachytherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and docetaxel in second-line advanced NSCLC treatment. Sci Rep 15, 12650 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97918-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97918-z