Abstract

This study examines the use of low-value rice husk ash as a stabilizer to optimize the mechanical performance and strength of compressed earth blocks made with local soil from the Cauquenes Province, Chile. The use of locally sourced earth construction materials in Chile is limited by their lower compressive strength compared to conventional fired bricks, along with the demanding seismic conditions of the region. To address these limitations, this study details the methodology for collecting, preparing, and mixing raw materials to manufacture compressed earth blocks, compacted under 10 MPa using a novel cylindrical polylactic acid mold designed for miniaturized samples. Fourteen different samples representing nine mixtures of rice husk ash and soil were evaluated using an optimized experimental design. The resulting mechanical properties, including fracture analysis correlated with performance, were assessed through statistical analysis to determine the significance of the optimum mix and the observed trends in strength, modulus of elasticity, yield strength, and associated plastic work. The maximum compressive strength achieved was 3.3 MPa. Notably, the optimum mix of rice husk ash-stabilized compressed earth blocks exhibited a 60% increase in strength compared to pure soil compressed earth blocks, demonstrating the potential of rice husk ash as a cement substitute.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increase in the world’s population and the consequent need for urbanization and infrastructure development are driving increased demand for cement and concrete. The production of cement is a major contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for approximately 8% of total carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions according to the United Nations Environment Programme1. This, in turn, increases the pressure to accelerate action to reduce the carbon footprint generated by the construction sector. The direct CO2emissions of cement are expected to increase by 4% globally by 2050, whereas cement production is expected to increase by 12% during the same period2. For this reason, in addition to taking measures to mitigate carbon emissions and improve energy efficiency in cement production, alternative sustainable materials in the sector are urgently needed3.

Among the available options for implementing cleaner and more advanced technologies in construction and significantly contributing to climate change, the development of compressed earth blocks (CEBs) incorporating different agroindustrial wastes has shown great potential. CEBs are composite materials made mainly of a mixture of soil and a small amount of water. These blocks are formed by compacting this mixture using manual or mechanical presses, resulting in solid or hollow rectangular prisms. Dimensions vary depending on the applicable standards, manufacturer or project specifications3.

Researchers have studied the incorporation of various additives to improve the performance of CEBs3,4,5,6,7,8,9. These additives can be grouped into two main categories: reinforcements and stabilizers. Reinforcements typically consist of natural or synthetic fibers, such as kenaf or polypropylene, which improve the tensile and cracking strength of the block. Stabilizers, or binders, are added to improve the overall strength and durability of the CEB. They can include ground materials, powders or ashes derived from organic or industrial by-products, such as ground olive dust, by-product ashes, lime and cement. An optimal combination of reinforcements and stabilizers can significantly improve the mechanical strength and performance of CEBs3. Researchers have explored various soil stabilization applications, emphasizing the importance of adopting environmentally sustainable alternatives to conventional cement-based stabilizers, such as fly ash (FA)-based geopolymers, to improve soil performance. Turkane and Chouksey (2022) identified 25% FA as optimal for improving soil strength and reducing shrinkage and subsidence behavior in flexible pavements10. In another study, they found that 20–30% FA effectively stabilizes low-plasticity soils while minimizing landfill waste and environmental impact11.

Sustainable construction materials and the revalorization of agricultural waste have shown promising results in recent years as viable approaches for addressing the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations. The production of cement, known as a major contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions, has motivated researchers to explore alternative stabilizers12,13. Chile produces approximately 30,000 tons of rice husk per year14. Rice husk represents about 20% of the volume of rice with husk. Rice husk ash (RHA), resulting from the combustion of rice husks, represents about 15–25% of the weight of rice husks15. This represents an estimated annual production of 4,500 to 7,500 tons of RHA in Chile. This abundant agricultural byproduct currently has limited economic use within the country16.

In addition, compressed earth blocks, an ancient construction technique, have gained renewed interest because of their potential for reduced environmental impact compared with energy-intensive materials such as concrete and fired bricks17. However, compressed earth blocks often exhibit lower compressive strength than conventional construction materials, limiting their wider adoption in the construction industry.

To address the challenge of sustainable development goals and contribute to the growing body of research on the pozzolanic efficiency of agroindustrial waste for carbon footprint reduction, this study investigates the potential of rice husk ash to enhance the mechanical performance of compressed earth blocks. Common stabilizers such as lime and cement are used in compressed stabilized earth blocks (CSEBs), enhancing the cohesion of the mixed materials through chemical reactions and producing stronger compounds3. Previous studies have demonstrated that partial substitution of cement with supplementary cementitious materials such as fly ash18, ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS)19,20, and RHA21can enhance the mechanical and durability properties of construction materials, including concrete, mortar, and stabilized soils. While much research has focused on the benefits of supplementary cementitious materials in concrete and mortar applications20, their effectiveness in soil stabilization has also been well documented10,22,23,24,25. The incorporation of supplementary cementitious materials in stabilized soils follows similar principles as in cementitious materials, where reactive silica interacts with calcium hydroxide to form secondary calcium silicate hydrates (C-S-H), improving matrix structure, strength development, and long-term durability23. Specifically, in CEB stabilization, supplementary cementitious materials such as RHA and GGBS have been found to enhance particle bonding, reduce permeability, and increase compressive strength due to their pozzolanic activity26. However, excessive amounts of RHA may negatively impact mechanical properties by reducing density and cohesion in the mixture, as observed in previous research on concrete and soil applications3,17,21,22,27,28,29.

The optimization of compressed earth block performance has primarily focused on evaluating compressive strength30,31,32. However, flexural or bending behavior33,34,35, including measurements of deformability to determine the capability of the material to withstand strains is also commonly assessed. Reporting additional properties such as water absorption, erosion resistance, abrasion resistance, drying shrinkage, volume variation, and porosity would provide complementary characterization data of CEB but only once the optimal mixture for maximum strength using local soils and raw materials has been achieved. The influence of particle size distribution can affect the mechanical properties of compressed earth blocks. However, Turco et al. (2024)36found that while different bulk densities were achieved using soil particle sizes from 2 mm to 12.5 mm sieves, there was no significant difference in the mechanical strength of the compressed blocks. This suggests that the particle size distribution may not be the primary factor influencing the mechanical performance of CEB. Therefore, the current research focuses particularly on investigating the optimal mixture proportions of soil and rice husk ash for CEB based on their compressive loading response, as this is a crucial parameter for their structural performance and building code compliance4,31,37,38.

Rice husk ash is considered a waste material that can be effectively utilized in various applications. It can be used as a supplementary cementitious material, a source of silica for ceramic production, and a soil stabilizer for compressed earth blocks to enhance their mechanical performance39,40. Beyond these uses, other ashes can also be employed as a pozzolanic additive40, in concrete to improve durability, as a filler in polymer-based composites to enhance mechanical properties, and as a raw material for the synthesis of advanced materials like zeolites and silica-based catalysts. Research has shown that valorized materials, such as rice husk ash, when incorporated as a soil stabilizer, can significantly improve the compressive strength of compressed earth blocks41. For the construction of masonry facing, superior performance in terms of strength and durability has been reported42. The compressive strength achieved by a CEB stabilized with 12 wt% of calcium carbide residue (CCR) using an 8 wt% of RHA was 6 MPa. 36% higher strength compared to the 4.42 MPa reached by a similar CSEB without RHA, leading a similar strength (6.2 MPa) reached by a CEB only stabilized with cement content of 8% by weight42. These results provide some evidence on the performance of CEB incorporating RHA, however, different mixture proportions with local and different soils should be investigated to evaluate their effectiveness and to determine the optimal amount of locally sourced rice husk ash content for the highest load-bearing capacity of CEB.

This study investigated the use of industrial rice husk ash residue as a stabilizer for compressed earth blocks manufactured with local soil from Cauquenes Province, Chile. The primary focus of the research is to address the mechanical performance and strength characteristics of the resulting construction material. A key contribution of this work lies in optimizing these properties to enhance the feasibility of using compressed earth blocks in construction. The industrial or local production of compressed earth blocks in Chile is still limited because of their relatively low compressive strength compared with that of conventional fired clay bricks, as well as the harsh seismic conditions prevalent in the region. This reduced mechanical performance has been a significant barrier to the wider adoption of this sustainable construction material in the country.

A new laboratory method was developed to efficiently investigate different CEB compositions. This method utilizes smaller-scale specimens produced with a 3D-printed43polylactic acid mold, significantly reducing raw material usage, energy consumption, and production time44. The polylactic acid (PLA) mold, designed according to Chilean standard NCh 1017. EOf 7545, was validated for strength and optimized topologically using CAD and CAE software46,47. This approach enables efficient analysis of various mixtures by optimizing the manufacturing process while adhering to compression strength testing standards. The use of the PLA mold under 10 MPa compaction pressure has proven feasible and viable for CEB sampling production. Fourteen miniaturized CEB specimens, fabricated with these eco-friendly molds and a reduced experimental design, were tested under uniaxial compression to determine the influence of RHA content on strength, elastic limit, and elasticity modulus. Statistical analysis of the results revealed trends in mechanical responses, correlated with observed fracture behavior and RHA content, providing valuable insights into the compressive behavior of miniaturized CEBs and informing the optimal use of RHA as a stabilizer in sustainable CEB construction.

The paper is divided into 4 main sections. Section 2 describes the raw materials, manufacturing methods, and testing protocols for the mechanical characterization of the proposed miniaturized samples. Section 3 presents the experimental mechanical results in terms of the maximum strength, modulus of elasticity, elastic limit and associated plastic work. A statistical analysis of the observed experimental trends of the responses of compressed earth block samples manufactured with different proportions of rice husk ash is also provided in Sect. 3, and the overall analysis, conclusions, and perspectives for future work are summarized in Sect. 4.

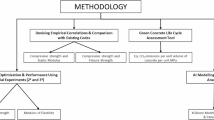

Materials, manufacturing, and testing methods for compressed earth blocks

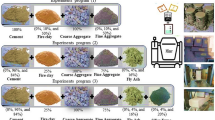

Raw materials

Sustainable construction materials minimize environmental impact throughout their lifecycle, from resource extraction to disposal, while ensuring the continuous availability of raw materials. This involves using renewable or recycled materials, reducing energy consumption during manufacturing and use, maximizing durability to minimize replacements, and limiting pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Sustainable materials also prioritize health and well-being by being non-toxic and often contribute to local economies through the use of locally sourced resources.

In this research, the compressed earth blocks were manufactured using soil and rice husk ash. Soil was collected from a test pit within a small area in Cauquenes Province, Chile. Sieve analysis confirmed acceptable grain size, and thorough mixing ensured a homogeneous composition. The region is characterized with abundant, underutilized soil – some suitable for limited agriculture and some with no agricultural value48. This zone also experiences reduced economic activity49.

The RHA was obtained as bottom ash from a local rice processing facility, without additional pretreatment such as controlled calcination. This approach promotes direct reuse, minimizing energy consumption while maintaining the naturally available properties of RHA for stabilization.

Table 1presents the geotechnical properties and chemical composition of both materials. The soil, classified as sandy clay loam according to the United States Department of Agriculture classification (USDA), exhibits low plasticity (Plasticity index, PI = 11%), indicating minimal risk of expansion or contraction due to moisture variations. Its chemical composition, determined by X-ray diffraction, reveals a predominance of silica (SiO₂ − 56.53%), followed by alumina (Al₂O₃ − 23.49%) and iron oxide (Fe₂O₃ − 9.81%), characteristic of this soil type. Minor alkaline compounds (CaO, K₂O, Na₂O) are also present. The RHA chemical composition shows a high silica content (76%), with moderate amounts of Al₂O₃, Fe₂O₃, K₂O, and CaO, contributing to its dark grey color. The balanced proportions of sand, silt, and clay in the soil contribute to the favorable structural stability and load-bearing capacity of the CEBs. The low plasticity index further minimizes cracking or deformation during drying due to moisture fluctuations50,51.

The soil preparation for the manufacture of compressed earth blocks follows the methodology proposed by Valenzuela et al. (2024)3. This process involves screening the soil to separate and remove any nonsoil materials, such as plant roots and hard rocks. The soil lumps are then broken down by crushing, and the soil is sieved with an opening size of 0.6 mm (No. 30 ASTM E11) to achieve homogenization. This ensures that the soil is properly conditioned for the correct molding and production of compressed earth blocks.

Novel manufacturing process for miniaturized CEB samples

For the manufacture of compressed earth blocks, the raw materials of soil, demineralized water, and rice husk ash were combined in varying proportions to assess the stabilizing impact of each CEB mixture. Demineralized water was used to minimize interference from dissolved ions, ensuring that observed soil-RHA interactions were intrinsic and uncontaminated. This controlled approach, consistent with similar studies like Nshimiyimana et al. (2019)52, enhances the accuracy and reliability of the results regarding RHA’s pozzolanic capacity and its impact on soil stabilization. A water content of 19% by dry weight (soil + RHA) was used to ensure adequate plasticity and adhesion during compaction. This is consistent with findings from Nshimiyimana et al. (2018)53, who reported using approximately 17% water content for dry mixtures, and aligns with values obtained from the drop weight test, similar to the work of Hany et al. (2021)17. Studies on pure soil CEBs report optimal water content between 14 and 19%: Talibi et al. (2023)54used 14%, Muntohar (2011)39used 19%, and Elahi et al. (2020)27used 15%. While standards like CRATERRE and UNE 41410:2023 recommend 14% and 12% respectively, Asha et al. (2020)41 observed a higher water content (22%) with RHA addition, attributed to increased water absorption, supporting the 19% value used in this study.

The appropriate proportions of each raw material were determined based on the ranges reported in the literature and the experimental design of the mixtures proposed in this research. The specific proportions used for mixing and producing the CEB samples are provided in Table 2. Each mixture is labeled with an identifier (M1–M9) for reference in statistical analysis and performance evaluation. The soil replacement content ranges in weight between 2.7% and 20%, whereas 100% soil content is used for the two control samples (M3). A total of fourteen samples with nine different mixtures were prepared and manufactured separately via the established process.

The raw materials were mixed manually in a container for 5 min until a homogeneous mixture was obtained and then poured into a cylindrical mold of the CEB samples manufactured with polylactic acid (PLA) via 3D printing technology.

The cylindrical mold for the miniature CEB samples was designed based on topological optimization of the infill density, providing an efficient material distribution to achieve the maximum strength‒to‒weight ratio46. The mold design incorporated a minimum safety factor of 1.5, ensuring structural integrity when applying a compaction pressure of 10 MPa. This pressure, reported as high in literature55, was selected based on studies indicating standard values between 2 and 10 MPa56,57,58. While higher pressures generally increase compressive strength due to densification6,59,60, this study prioritized sample reproducibility and consistency within equipment constraints. Future research could further investigate the effects of compaction pressure on RHA-modified CEBs, particularly considering feasibility in manual or local production methods.

To apply compaction pressure to the wet raw material mixtures (Fig. 1a) and produce miniature CEB samples, the following steps were performed. The mold containing the raw material mixture, separated by two small polylactic acid discs, was mounted on a base part and equipped with an upper piston made of a similar material (Fig. 1c). This assembly was then placed in an Instron 3369 universal testing machine (Fig. 1b). A controlled load of 0.23 kN/s was applied through the tungsten carbide discs of the uniaxial machine. This load was transmitted to the piston mold, the upper separation disc, and consequently, the pressure was transmitted to the raw material mixture. The load was increased until a maximum of 7.07 kN was reached, corresponding to an internal compaction pressure of 10 MPa. Owing to the nature of the mixture, air escaped from the upper and lower parts of the cylindrical mold, whereas residual water escaped from the interface between the separator piece, the internal cylindrical surface of the mold, and the base part designed with water container surfaces. To emulate a manual hydraulic press, the displacement of the uniaxial machine discs was stopped once the maximum 7.07 kN load for 10 MPa was reached. During a dwell period, the compaction pressure decreased to a minimum of 8.5 MPa, and the initial loading rate was then reapplied until 10 MPa of compaction pressure was reached again. This process was repeated seven times until the compaction pressure stabilized. Finally, the sample was removed from the mold via a specialized piece designed for that purpose (Fig. 1b, stage 3).

The manufacturing process was repeated for the different mixture compositions (Fig. 1d). After manufacturing, all miniature CEB samples were placed in sealed polyethylene bags for a 6-day curing period. The CEBs were then removed from the bags and allowed to dry at room temperature in the laboratory for 26 days. The dimensions of the cylindrical samples were 30 mm in diameter and 60 mm in height.

Experimental methods for evaluating the compressive mechanical behavior of CEB samples

The compressed earth block samples obtained from the shape of the cylindrical mold were tested via compressive strength tests. The mechanical performance of the samples was evaluated to assess the stabilizing potential of rice husk ash in soil-water mixtures. The samples were tested with the same dimensions as those generated when the CEB samples were produced with the cylindrical mold. Standardized cylindrical specimens (h/d = 2.0), as recommended by ASTM C39, were used for compressive strength testing. This geometry ensures uniform stress distribution and minimizes edge effects, leading to more reliable strength measurements compared to prismatic or cubic specimens, which are known to exhibit higher apparent strength due to stress concentrations at the corners61. While prismatic specimens may appear more representative of the actual block geometry, the standardized cylindrical test provides a more consistent and comparable measure of the material’s inherent compressive strength (ASTM D1633-17; ASTM C39/C39M-21). This approach allows for better quality control and facilitates comparison with existing literature. The standardized h/d ratio of 2.0, as specified in ASTM C39, offers a balance between measurement accuracy and test efficiency.

The tests were carried out in accordance with the ASTM C39 standard using an Instron 3369 universal testing machine with a maximum load capacity of 50 kN. The high accuracy of the machine (± 0.5% up to 250 N, ± 1% from 100 N to 250 N) ensured precise force measurements, minimizing errors in compressive strength calculations62.

All the CEB samples were placed centrally between the two steel plates of the Instron machine and loaded until the initial failure of the samples was reached. The displacement velocity control for the compression test was set at 1 mm/min. The same test procedure was applied as that used in the study conducted by Valenzuela et al. (2023)13. The results obtained from this compressive strength test are explained in detail in Sect. 3.

A lack of universally accepted standards is found in building codes for the minimum dry compressive strength of compressed earth blocks3. Various standards, such as BIS: 1982, ARSO: 1996, AFNOR: 2001, ICONTEC: 2004, NMAC, 2016, AENOR, 2008, ASTM E2392, 2016, and IS 1725: 2013, suggest a minimum dry compressive strength of 2 MPa for CEBs. However, other standards, such as NMX-C-404-ONNCCE: 2012 and SLS 1382: 2009, report a minimum strength above 7 MPa.

Manufacturing process of miniaturized compressed earth blocks: (a) raw material mixing, (b) uniaxial machine, (c) compaction in a cylindrical mold (SolidWorks 2021 Student Edition: https://www.solidworks.com/product/students), and (d) CEB samples with varying soil-RHA compositions.

Postprocessing data from compression experiments

The performance of the compression specimens was determined from the engineering stress-strain curve. Load vs. displacement measurements from the uniaxial testing machine were post-processed and appropriately corrected using the method proposed by Tuninetti et al. (2020)63. Compressive strength or ultimate stress was identified as the maximum strength in the stress-strain curve. Young’s modulus was determined from the initial linear portion of the stress-strain curve using a linear regression fit between 0.2 and 0.8 of the initial yield point64. The initial yield point was determined using the 0.2% strain offset method and the associated plastic work65, defined as the area under the stress-strain curve to the initial yield point minus the reversible energy of elastic recovery, was reported.

Ultimate compressive strength is a fundamental parameter for determining the optimal mixture composition. The ultimate compressive strength indicates the maximum stress a CEB can withstand before complete failure, which is critical for designing safe and reliable wall structures. The modulus of elasticity allows structural analysis predictions of walls under various loading conditions to ensure that structures can withstand the expected stresses and strains. Finally, the initial yield and associated plastic work indicate the maximum loads that the CEB or CEB walls can withstand before internal damage, but not complete failure, occurs. At this stage, microcracks may appear and grow until the damage is greater than the degree of block strengthening. The data collected from the compression tests were analyzed to determine the effects of the rice husk ash content on the mechanical properties.

Statistical analysis of the compressive response

Comparative statistical analysis is applied between a linear model and a quadratic model relating the RHA content in CEB to the responses or dependent variables in terms of the ultimate compressive strength, Young’s modulus, yield stress and associated plastic work. To evaluate the significance of the linear and quadratic regression models on the experimental data, t tests and F tests are applied, and p values are used to draw conclusions about the statistical significance of the models. A linear regression model, if significant, allows the determination of a global trend between the compressive response of CEB and the ash content, whereas a quadratic model could provide an optimal range of ash content for maximum compressive strength.

The formulation of the linear regression model is expressed mathematically according to Eq. (1):

where \(\:y\) is the dependent variable, \(\:x\) is the independent variable, \(\:{\beta\:}_{0}\) is the intercept, and \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}\) is the slope. To determine the significance of the linear regression model, statistical hypothesis tests are performed on the significance of the individual model with the coefficient of the linear term (\(\:{\beta\:}_{1}\)) and the overall model through the p value.

The t test is applied to evaluate the significance of the independent variable (ash content) in predicting the dependent variable. The t test for the slope coefficient (\(\:{\beta\:}_{1})\) is expressed as follows:

-

Null hypothesis (\(\:{H}_{0}\)): There is no linear relationship between the \(\:x\) variable and the \(\:y\) variable. Therefore, \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}\)=0.

-

Alternative hypothesis (\(\:{H}_{1}\)): There is a significant linear relationship between the variable \(\:x\) and the variable \(\:y\). Thus, \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}\ne\:\)0.

To determine if the linear function obtained from the overall regression model is statistically significant, an F test is performed, and the significance F of the overall model is analyzed. The F test is used to evaluate the null hypothesis that the coefficients of the regression model are all equal to zero, indicating that the model is not significant overall. The hypotheses for the F test are as follows:

-

Null hypothesis (\(\:{H}_{0}\)): The overall regression model is not statistically significant.

-

Alternative hypothesis (\(\:{H}_{1}\)): The overall regression model is statistically significant.

If the significance F value, which represents the p value for the F test, is less than the chosen significance level (in this case, 0.05), then the null hypothesis is rejected. This would indicate that the overall regression model is indeed statistically significant and that at least one of the regression coefficients is nonzero. The null hypothesis suggests that there is sufficient evidence to conclude that the linear relationship obtained from the overall model is statistically significant.

The formulation of the quadratic-type nonlinear fitting model is expressed mathematically according to Eq. (2):

With respect to the linear model, this model adds an additional term \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}\), which is a coefficient of the quadratic term \(\:{x}^{2}\). The statistical hypothesis test, t test, and F test are performed again to evaluate the statistical significance of the quadratic model via the p value.

The t test is used to evaluate the individual significance by means of the coefficient \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}\) of the independent variable, presented as follows:

-

Null hypothesis (\(\:{H}_{0}\)): There is no quadratic relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. The quadratic term does not improve the model, and the relationship between the variables is best modeled with a linear relationship. Therefore, \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}\)=0.

-

Alternative hypothesis (\(\:{H}_{1}\)): There is a significant quadratic relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. The quadratic term is significant and improves the model. Hence, \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}\ne\:\)0.

To determine if the quadratic relationship obtained from the global model is statistically significant, the F test compares the significance of the linear model with that of the quadratic model. In this case, the F test is formulated as follows:

-

Null hypothesis (\(\:{H}_{0}\)): The quadratic model does not fit significantly better than the linear model.

-

Alternative hypothesis (\(\:{H}_{1}\)): The overall fitting model is significant as a whole and is better than the linear model.

Mechanical performance of CEBs under compressive loading

This section presents the experimental results of strength, elasticity, and yield strength with the associated plastic work of compressed earth blocks manufactured with different rice husk ash contents between 0 and 20 wt% obtained from compressive loading testing. Fracture behavior is characterized and classified according to failure mode and mechanical strength. The experimental trends observed in the responses are also statistically analyzed to support the findings. Finally, the optimal mixture of soil with ash that improves the mechanical performance and strength characteristics of the resulting sustainable cement-free construction material is identified.

Effect of RHA stabilizers on the stress‒strain response

The mechanical properties of the CEB samples were analyzed through experimental tests of their uniaxial compression resistance. The maximum compressive strength (σUlt), yield strength (σe), Young’s modulus (E), and associated plastic work (Wp) were determined and compared for the different investigated material compositions. Figure 2a shows the stress‒strain behavior determined from mechanical compression tests of the CEB samples with different contents. The darker blue curve indicates lower rice husk ash content. Figure 2b and c show the characteristic mechanical properties of the samples processed from the curves shown in Fig. 2a. Data points from Fig. 2a were extracted and plotted in Fig. 2b (ultimate stress, Young’s modulus) and Fig. 2c (yield stress, plastic work per unit volume). Blue markers indicate ultimate stress and yield stress, while red markers represent Young’s modulus and plastic work. For 5.6% RHA, three samples were tested; for 0%, 14.3%, and 20% RHA, two samples were tested, whereas for 2.7%, 7.8%, 12.1%, and 16.9% RHA, only one sample was tested. Fully filled markers denote the first-sample test, unfilled markers the second-sample test, and raster-filled markers the third-sample test for a specific mixture formulation given in Table 2. This experimental design (Table 2) ensures a representative range of soil-RHA compositions while optimizing resources.

The compressive strength ranges between 1.6 and 3.3 MPa, whereas the elastic modulus is between 72 and 180 MPa (Fig. 2b). The lowest strength is found for the CEB sample with no rice husk ash content, and the maximum values occur for ash contents of 10 and 14.3 wt%. A trend is visible in the results; lower ultimate strength values are globally obtained for samples with lower rice husk ash contents. However, the maximum content of rice husk ash close to 20 wt% does not yield the maximum strength values. In terms of linear elastic behavior, the slope representing the elastic modulus shows a high dispersion of values with no clear correlation with the ash content (Fig. 2b).

The control samples without the addition of rice husk ash presented compressive strengths between 1.6 and 1.9 MPa, which did not meet the minimum requirement of 2 MPa specified by several building codes for compressed earth blocks (BIS: 1982, ARSO: 1996, AFNOR: 2001, ICONTEC: 2004, NMAC: 2016, AENOR: 2008, ASTM E2392: 2016, and IS 1725: 2013). In contrast, all the CEB samples with the addition of rice husk ash achieved an acceptable level of compressive strength according to these standards. It is important to note that directly translating the compressive strength of cylindrical specimens to rectangular CEB is not accurate due to differences in stress distribution and failure mechanisms. A correction factor should be applied to estimate the strength of rectangular blocks based on previous studies3. Future work should compare specimens under the same conditions for better characterization.

Samples with 0% RHA exhibit the lowest deformation capacity, failing early at the lowest maximum compressive stress. These samples show almost no plastic deformation, indicating brittle behavior. Samples with RHA content between 10% and 14.3% by weight demonstrate the highest compressive strength and maximum plastic deformation. RHA contents both above and below this range result in decreased peak compressive strength and reduced deformation at failure. Furthermore, RHA contents exceeding 14.3% show even less plastic deformation compared to those below the optimal range, suggesting increased brittleness at higher RHA concentrations (Fig. 2a).

Strength mechanism of soil stabilization with respect to chemical analysis is well reported in the literature. The strength mechanism in RHA-stabilized CEBs is primarily governed by pozzolanic reactions and particle bonding. The high silica content (76%) in RHA reacts with calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂) from soil minerals to form secondary calcium silicate hydrates (C-S-H), enhancing matrix cohesion and compressive strength23. The chemical composition of the soil (SiO₂ − 56.53%, Al₂O₃ − 23.49%, Fe₂O₃ − 9.81%) also contributes to the stabilization process, as alumina and iron oxides participate in the formation of calcium aluminate hydrates (C-A-H), which further strengthen the soil structure22. Additionally, the presence of alkaline oxides (CaO, K₂O, Na₂O) in RHA facilitates cation exchange, reducing soil plasticity and improving aggregate interlocking24. This effect is particularly relevant for low-plasticity soils, where the interaction between RHA and clay minerals leads to increased load-bearing capacity and decreased shrinkage potential25. The chemical reaction between SiO₂ and Ca(OH)₂ is time-dependent, meaning that strength development continues over an extended curing period, contributing to the long-term durability of the stabilized blocks26.

RHA content significantly affects the yield strength and associated plastic work (Fig. 2c). The results show that the optimum RHA content (10–14.3 wt%) provides the best performance with yield stress reaching a maximum value of 2.8 MPa indicating higher yield strength and plastic work a maximum value of 0.54 J/mm³, indicating higher ductility and energy absorption. The relationship between ultimate compressive strength and yield strength is assessed to evaluate the load-bearing capacity and long-term stability of CEBs with varying RHA content. The comparative analysis reveals that with increasing RHA content value from 0 to 14.3% by weight, an increasing tendency to increase compressive strength and yield stress is observed, suggesting a balance between stiffness and ductility, offering superior structural performance by facilitating higher effective load distribution capacity. The 14.3 wt% RHA content is considered optimal as it maximizes load distribution efficiency and the balance between strength and ductility. A RHA content above 14.3 wt%, both compressive strength and yield stress decrease. Yield stress drops from 2.8 MPa (14.3 wt% RHA) to 2 MP (20 wt% RHA), while compressive strength declines 0.7 MPa. This indicates that the excess RHA in the CEB mix saturates the mix, reducing cohesion, generating cracks instead of reinforcing the matrix and weakening the microstructure to the point of generating lower load transfer efficiency.

Fracture modes of CEBs under uniaxial compression

The effects of different rice husk ash contents on the fracture modes of the tested samples under compressive loading are shown in Fig. 3. The dashed line in Fig. 3a indicates failure in the samples, which can be divided into two main fracture mode groups: single columnar/shear failure and multiple shear failure (local cracks with flake-shaped failure). These two groups of failures are counted separately and subdivided into three ranges of strength and elastic modulus according to the reported experimental values: high, middle and low ranges (Fig. 3b). Low to moderate strength counts are associated with single columnar/shear-dominated failure, whereas multiple shear failure cracks (flake-shaped failure) correlate with the groups reporting the highest compressive strength range. In terms of the elastic modulus, moderate to high values are also related to multiple shear cracks, whereas low to moderate Young’s moduli are correlated with a columnar/shear failure mode. Note that only one count of samples classified with shear/columnar failure has a high Young’s modulus. However, this sample also shows minor zones of multiple cracks (0% RHA sample shown in Fig. 3a). The analysis of failure modes reveals a clear correlation between the mechanical properties and the fracture behavior of the CEB samples, where multiple shear failure cracks in the samples are associated with a higher strength and elastic modulus, whereas more columnar/shear fractures lead to a lower strength and elastic modulus.

Therefore, the variation of RHA content influences the microcracking patterns and internal damage, as shown in Fig. 3. For CEB from 10 to 20% RHA, multiple shear failure cracks are observed while for CEB from 0 to 7.8% RHA, columnar and simple shear failure are observed. CEB without RHA has a weaker block matrix, resulting in a material with low durability, susceptible to stress cracking, with brittle CEB failing at 1.6 MPa compressive stress. The positive influence of the addition of RHA to the mix occurs up to a maximum value of 14.3% RHA at which a trend towards increased yield strength and associated plastic work is observed. However, when exceeding a content of 14.3% by weight of RHA the yield strength and associated plastic work decreases, suggesting that an excess of RHA reduces the cohesion of the CEB, which generates brittleness in the CEB, decreasing the ability of the material to control internal damage and leading to premature failure with a compressive stress of 2.6 MPa (for CEB with 20% RHA) compared to 3.3 MPa for CEB including 14.3% by weight of RHA.

Mapping the trend: RHA content and its effect on CEB mechanical performance

The different linear and quadratic models fitted to the observed compressive response (Fig. 4) of the samples in terms of rice husk ash content are presented in Table 3. A statistical analysis is subsequently performed to evaluate whether the relationships between the variables are better represented by a quadratic or linear model (Table 4). This comparative analysis is carried out by comparing the R2, adjusted R2, t tests, and F tests.

In the quadratic regression of the ultimate stress, the coefficient of determination (R²) obtained is 0.77, while in the linear regression, it is 0.58. This means that 77% of the variability in ultimate stress is explained by the RHA content in the quadratic model, compared to 58% in the linear model. To further evaluate the models, the adjusted R² values were compared. Adjusted R² modifies the R² value by considering the number of predictors in the model, providing a more accurate measure of how well the model fits the data by penalizing for the inclusion of unnecessary variables. For the linear regression, the adjusted R² is 0.55, while for the quadratic regression it is 0.73. These values indicate that the quadratic model not only explains a larger proportion of the variability but also does so without overfitting, making it a better fit for the data than the linear model. By analyzing these metrics, it is evident that including the quadratic term improves the predictive capability and overall reliability of the model.

By means of the significance of the coefficients for the \(\:x\) term of the linear model and for the \(\:{x}^{2}\) term of the quadratic model, the best fit is verified, also considering the significance of the model as a whole through the F test. For the linear regression model, \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}=0.0545\) indicates a positive slope for the fit curve, and for the quadratic regression model, \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}=-0.0053\) indicates a concave curve; therefore, the value of the quadratic term \(\:{x}^{2}\) is nonzero and is significantly better than the value of the \(\:x\) term. The negative coefficient β₂ in the quadratic model contributes to a concave-downward curve when modeling the relationship between ultimate compressive strength and RHA content. This implies that there is an optimal RHA content for maximizing compressive strength. Adding RHA up to this optimal point increases strength, but beyond it, further additions of RHA decrease strength. The p-value of 0.011 for β₂ confirms that this quadratic term is statistically significant, indicating a genuine nonlinear relationship. Therefore, simply using a linear model (which assumes a constant increase in strength with increasing RHA) would be inappropriate. The quadratic fit suggests an optimal RHA range around 15 wt%, highlighting the importance of careful ash content selection to avoid diminishing returns and potential weakening due to decreased density and cohesion beyond this optimum.

The p value of 0.011 associated with the coefficient \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}\) is less than 0.05, which indicates that the quadratic term is significant and contributes to the model fit (Table 5). Finally, both models are also compared through the F test (Table 6), and the p value for the linear model is 0.0015, whereas for the quadratic model, the p value is 0.0003. The F test presents a low p value, so the null hypothesis is rejected (Sect. 2.5). This finding suggests that there is a significant quadratic relationship between the dependent variable (ultimate stress) and the independent variable (rice husk ash content), confirming that the quadratic model significantly improves the fit compared with the linear model. Similar fitting results are achieved with the quadratic model for yield stress and the associated plastic work. Therefore, a significant quadratic trend of the ultimate and yield stress values and the associated plastic work at initial yielding with the variation in the rice husk content is found. In conclusion, the F test results strongly support the superior predictive capability of the quadratic model (lower p-value = 0.0003) compared to the linear model (p = 0.0015), indicating that the quadratic model explains a significantly greater proportion of the variance in the data. This reinforces the conclusion that mechanical responses, particularly compressive strength, exhibit a nonlinear relationship with RHA content, characterized by a peak at optimal RHA levels, which is better captured by the quadratic model.

The resulting Young’s modulus from compression tests in terms of RHA content follows a different behavior. The R2for the linear regression is 0.0146, indicating that the linear model explains only 1.46% of the variability in the Young’s modulus, whereas the quadratic model has a higher R2of 0.056 (5.6% of the variability in the Young’s modulus). The adjusted R2 for the linear model is −0.067, and the adjusted R2for the quadratic model is −0.116, which indicates that both models present low R2 values, and that the inclusion of the quadratic term does not improve the model. This makes it more complex, and the fit worsens when a greater number of parameters are considered. Therefore, none of the models fit the variability in the Young’s modulus with respect to the rice husk ash content. Other factors not considered in this analysis may influence the variability and dispersion of the experimentally obtained Young’s modulus results. The statistical significance indicates that the p value associated with the coefficient of the quadratic term \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}=-0.15\) is 0.5, and for the coefficient of the linear term \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}=-0.53\), the p value is 0.6. Furthermore, the F test for both models indicates high p values (0.68 for the linear model and 0.73 for the quadratic model), implying that neither model is significant in its entirety and that it cannot effectively explain whether there is a significant relationship between the dependent and independent variables. This lack of model fitting of Young’s modulus could be explained due to its more sensitivity nature to sample inconsistencies and equipment limitations in measuring displacement than compressive strength. Small variations in sample surfaces can lead to inaccurate strain values. In contrast, compressive strength depends solely on load measurements and initial geometry, while Young’s modulus depends on both load and displacement. Therefore, the error in Young’s modulus measurements is assumed to be higher due to the combined influence of these two error sources.

Figure 5 presents the residuals plotted against the independent variable (x) to validate the regression model. The residuals are randomly distributed around the red line in the quadratic model, in contrast to the linear model, where the residuals are distributed in the form of a specific pattern. No significant difference is observed in the residual plots for the Young’s modulus. Furthermore, the absence of a discernible pattern in the residuals of the quadratic model reinforces the conclusion that this model accurately captures the relationship between the rice husk ash content and mechanical properties, thereby providing a reliable framework for predicting the performance of compressed earth blocks.

Optimal mixture composition of CEB stabilized with RHA for sustainable construction

The use of ash stabilizers from agro-industrial waste due to their favorable mechanical characteristics has been the interest of previous research. Lime and wood ash mixed with 2.5%, 5%, and 7.5% cement were found to be effective in improving CSEB properties. The optimal ratios for enhanced compressive strength found by Hwang et al. (2018)66were 5% lime with 5% cement, and 5% wood ash. Elahi et al. (2020)27investigated sawdust ash content with cement mixtures, finding compressive strength increased by at least 21% compared to non-stabilized CEBs. According to Yatawara & Athukorala (2021)67, incorporating 7.5% RHA in clay soil CEBs with a 1:15 ordinary Portland cement-to-clay ratio and 20 mL/kg-cement resin adhesive increased compressive strength by 26%, reaching 4.06 MPa. In contrast, our study used sandy clay loam soil without additional cementitious binders or resin adhesives, achieving a maximum compressive strength of 3.3 MPa at 14.3% RHA, representing a 60% increase over control CEBs. The differences in soil type and stabilizers influence strength. Lower RHA content (7.5%) combined with OPC and resin enhanced strength in clay-rich soil, whereas in sandy clay loam, a higher RHA content (14.3%) was required to optimize strength. These results highlight the importance of soil type in determining optimal RHA replacement levels for stabilized CEB.

Building upon these findings, this study focused on RHA as the sole stabilizer to enhance the sustainability of CEBs. RHA content varied from 0 to 20 wt% and the optimal content was determined to be 15.1 wt%, yielding a predicted compressive strength of 3.0 MPa (using a quadratic model) and a maximum experimental value of 3.3 MPa. These results comply with several international earth construction standards (BIS: 1982, ARSO: 1996, AFNOR: 2001, ICONTEC: 2004, NMAC, 2016, ASTM E2392, 2016, and IS 1725: 2013), supporting RHA as a sustainable construction material.

Due to their enhanced ultimate and yield stress, RHA-stabilized CEBs offer significant advantages for sustainable construction. These improvements enable RHA-stabilized CEBs to meet international standards for load-bearing applications, validating their use as eco-friendly building materials. The enhanced mechanical properties translate to improved structural performance, allowing the CEBs to support greater loads and broadening their application. Moreover, the increased yield stress enhances safety and durability by providing greater resistance to deformation, creating more resilient and lower-maintenance structures. Finally, using RHA contributes to resource efficiency by potentially reducing material usage, promotes waste utilization by replacing cement, and offers cost-effectiveness due to its local availability and low cost68,69,70,71.

Compared to cement-based stabilizers used in CEBs, RHA demonstrates its potential as an environmentally preferable stabilizer for sustainable construction. Cement production is a highly energy-intensive process that contributes approximately 8% to global anthropogenic CO₂ emissions72. A significant part of these emissions originates from clinker production, which requires high temperatures (approximately 1450 °C) and releases CO₂ from both fuel combustion and limestone decomposition73. Average CO₂ emissions from cement production range from 0.66 to 0.82 kg per kg of cement produced74. In contrast, the production of RHA is produced by the combustion process at significantly lower temperatures (500–800 °C), leading to a substantial reduction in emissions75. Furthermore, the incorporation of 15% RHA in concrete can reduce total carbon emissions by 15% while maintaining performance targets, according to Ro et al. (2024)74. In addition to CO₂ reduction, the use of RHA as an additional stabilizer mitigates waste disposal issues and improves the circular economy of agricultural by-products75. Table 7summarizes a comparative assessment of energy use and emissions between cement and RHA-based stabilizers. The results highlight that, although the combustion of RHA requires some amount of energy, the overall carbon footprint is still significantly lower than that of cement-based alternatives. Furthermore, cement’s reliance on virgin raw materials contrasts with RHA’s reuse of an existing agricultural by-product, which provides an additional sustainability benefit74,75.

These advantages promote wider adoption of RHA-stabilized CEBs as a more sustainable, durable, and economical building material. However, further research is needed to investigate other properties for compliance with quality and industrial standards, including water erosion, thermal conductivity, and shrinkage. A comprehensive life-cycle assessment and long-term performance testing under various environmental conditions (freeze-thaw cycles, humidity variations) are also recommended. Additionally, assessing large-scale production feasibility and refining the manufacturing process to enhance efficiency and industrial applicability would further support its adoption. The significant environmental impact of cement-based construction industry (40% of solid waste77,78, 38% of CO2 emissions3, and 68% higher water consumption compared to other industries) further underscores the importance of sustainable alternatives like RHA-stabilized CEBs.

The findings of our study address several key aspects of sustainability68,69,70,71, including the elimination of cement through the use of RHA as a stabilizer, which significantly reduces the carbon footprint associated with cement production77,78. By utilizing RHA, an agricultural byproduct, the method promotes circular economy principles and mitigates waste disposal challenges. The proposed material mixture demonstrates enhanced mechanical properties for CEBs, contributing to greater longevity and durability. Additionally, the methodology maximizes the use of locally available soil and RHA, reducing reliance on non-renewable materials and supporting large-scale industrial applications for sustainable construction. While demineralized water was used in this study to ensure experimental reliability, practical applications can rely on locally available water sources that meet quality standards, further enhancing sustainability and cost-effectiveness. Future research should explore the impact of different water sources on RHA-stabilized CEB performance. Although carbon footprint analysis and life cycle assessments remain essential for a comprehensive evaluation, they are identified as key areas for future exploration.

In addition to evaluating environmental impacts, practical considerations for implementing the curing method in field conditions should be considered. The 6-day curing period using sealed polyethylene bags employed in this study can realistically be adapted to field practices using simple and cost-effective methods common in CEB construction. Typical approaches include covering blocks with polyethylene sheets, damp burlap, or other moisture-retaining materials, effectively preventing rapid moisture loss and protecting the blocks from wind and direct sunlight. Future research could further investigate sustainable alternatives, such as locally sourced or biodegradable films, to enhance eco-friendly curing practices.

The testing method proposed in this study can be adapted for ashes from different sources within the sample size limits; however, its effectiveness depends on the specific properties of each ash type, meaning it may require modifications rather than being universally applicable. The effectiveness of ash as a stabilizer depends on key factors such as chemical composition, fineness, and reactivity, which vary depending on the source and processing conditions. In this study, RHA was selected due to its high silica content and pozzolanic properties, which contributed to strength development in CEBs. Other ashes, such as fly ash, wood ash, and sugarcane bagasse ash, may have different chemical compositions and reactivity levels, which can influence their stabilizing performance. To achieve similar performance in CEBs, specific adjustments in mix design (e.g., optimizing the ash-to-soil ratio, adjusting water content, or incorporating additional binders such as lime or clay) and processing conditions (e.g., finer grinding to increase reactivity, controlled burning temperatures to enhance pozzolanic activity, or pre-treatment to remove impurities) may be required. Future research should systematically evaluate various ash types under the same experimental conditions to determine their effectiveness in CEB applications. Key factors such as amorphous silica content, particle size distribution, and impurity levels should be analyzed to establish a broader understanding of how different ashes contribute to strength and durability.

Conclusions

This study investigated the use of agricultural waste material, specifically rice husk ash, as a stabilizer to optimize the mechanical performance and strength of compressed earth blocks made with local Chilean soil. The feasibility of using rice husk ash as an alternative to cement and lime for stabilizing compressed earth blocks was demonstrated. An optimal RHA content between 10% and 14% by weight maximizes both compressive strength and plastic deformation in compressed earth blocks. RHA contents outside this range result in decreased strength, reduced deformation, and increased brittleness. From the manufacturing and experimental testing, the following contributions and findings are highlighted:

-

A new laboratory mold made of polylactic acid allows efficient evaluation of the compositions of different miniaturized CEB cylindrical samples under a compaction pressure of 10 MPa.

-

The addition of rice husk ash significantly improved the compressive strength of the compressed earth blocks compared with that of the control samples without ash. The control CEB samples without ash reported a compressive strength of 1.6 MPa and did not meet the minimum compressive strength requirement of 2 MPa specified by the building codes.

-

All the CEB samples with the addition of rice husk ash achieved acceptable strength levels, with maximum values ranging from 3.0 to 3.3 MPa for 10 to 14 wt% ash from the total mixture.

-

Failure mode analysis demonstrated a strong relationship between mechanical properties and fracture behavior in CEB samples. Specimens exhibiting multiple shear failure cracks showed higher strength and elastic modulus, whereas those with columnar/shear fractures exhibited reduced strength and stiffness.

The calibrated linear and quadratic regression models describing the relationship between the compressive response and rice husk ash content were statistically evaluated to determine whether the data exhibited a linear trend or a local optimum in performance. Hypothesis testing was employed to assess the significance of the models and identify the most appropriate representation of the observed experimental trends. The following conclusions can be drawn from the t tests and F tests:

-

Both the linear and quadratic models yielded p < 0.05, indicating a significant relationship between the variables (ultimate stress, yield stress, and plastic work) and the RHA content.

-

The quadratic model explained approximately 77.3%, 78.1%, and 65.9% of the variability in the ultimate stress, yield stress, and associated plastic work, respectively, as a function of RHA content, providing a better fit than the linear model.

-

The quadratic model allowed us to determine an optimal local RHA content of 15.1% for maximum CEB strength with the investigated local raw materials.

-

The quadratic model suggests an initial increase in the ultimate strength as the RHA content increases, but after a certain point, the strength decreases. This could be because although RHA can act as a cementitious material, improving the strength up to a certain level, excessive amounts may negatively affect the mechanical properties due to a possible decrease in the density and cohesion of the material.

-

The RHA content did not significantly affect the Young’s modulus of the CEB samples obtained from the stress‒strain curves. The variability in this parameter may be due to factors such as dimensional variations in the samples and the sensitivity of the equipment used for deformation measurement, considering the relatively low strain levels involved.

This study demonstrated the feasibility of using RHA as a sustainable stabilizer to improve the mechanical properties of CEBs. The optimal RHA content between 10% and 14% resulted in a significant 60% compressive strength improvement compared to unstabilized CEBs, meeting building code requirements and confirming its potential for field applications. However, further research is necessary to address certain limitations. The long-term durability of RHA-stabilized CEBs under various environmental conditions, including water resistance, freeze-thaw cycles, and thermal stability, remains an important area for investigation. Additionally, the variability in RHA composition due to differences in processing methods and feedstock may influence its stabilizing performance, necessitating further studies. Large-scale production feasibility also requires optimization, considering energy consumption, supply chain challenges, and the need for efficient field curing methods. Additionally, a comprehensive life-cycle assessment and carbon footprint analysis is required to quantify the environmental impact of RHA-stabilized CEBs in comparison to conventional cement-based materials, to ensure their long-term sustainability benefits. Furthermore, compliance with building standards and regulatory guidelines is essential for the widespread adoption of this material. Future research should systematically evaluate these aspects to ensure the practical implementation of RHA-stabilized CEBs in diverse construction environments.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

UNIDO. New partnership agreed between the United Nations Industrial Development. Organization and the GCCA to drive industry decarbonization around the Globe. https://www.unido.org/news/new-partnership-agreed-between-united-nations-industrial-development-organization-and-gcca-drive-industry-decarbonization-around-globe (2024).

IEA and WBCSD. Technology roadmap: Low-carbon transition in the cement industry. https://www.wbcsd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/TechnologyRoadmapLowCarbonTransitionintheCementIndustry.pdf (2018).

Valenzuela, M. et al. Towards the development of performance-efficient compressed earth blocks from industrial and agro-industrial by-products. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 194, 114323 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2024.114323

Turco, C., Paula Junior, A. C., Teixeira, E. R. & Mateus, R. Optimisation of compressed earth blocks (CEBs) using natural origin materials: A systematic literature review. Constr. Build. Mater. 309, 125140 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125140

Bailly, G. C., El Mendili, Y., Konin, A. & Khoury, E. Advancing earth-based construction: A comprehensive review of stabilization and reinforcement techniques for adobe and compressed earth blocks. Eng 5, 750–783 (2024).

Ma, J. et al. Ultra-compressed earth block stabilized by bio-binder for sustainable building construction. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 21, e03523 (2024).

Subramanian, G. K. M., Balasubramanian, M. & Jeya Kumar, A. A. A review on the mechanical properties of natural fiber reinforced compressed earth blocks. Journal of Natural Fibers 19, 7687–7701; https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2021.1958405 (2021).

Bui, Q. B., Nguyen, T. P. & Schwede, D. Manually compressed soil blocks stabilised by fly ash based geopolymer: a promising approach for sustainable buildings. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–14 (2023).

Reyna-Ruiz, C., Gómez-Soberón, J. M. & Rojas-Valencia, M. N. Feasibility and application of local closed-loop materials to produce compressed and stabilized earth blocks. Materials 17, 3358 (2024).

Turkane, S. D. & Chouksey, S. K. Application of response surface method for optimization of stabilizer dosages in soil stabilization. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions 7, 106 (2022).

Turkane, S. D. & Chouksey, S. K. Design of flexible pavement thickness using stabilized high plastic soil by means of fly ash-based geopolymer. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 24, 2044035 (2023).

Miranda, A. et al. High-performance concrete from rubber and shell waste materials: experimental and computational analysis. Mater. (Basel). 17, 5516 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17225516

Valenzuela, M. et al. CEBs with GRC: fabrication, characterization, modeling, and correlation with microstructural fracture features. Mater. Today Commun. 37, 107028 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107028

Soto, Sergio. Arroz: temporada 2021/22 y perspectivas. Oficina de Estudios y Políticas Agrarias –Odepa. Ministerio de Agricultura. https://bibliotecadigital.odepa.gob.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12650/71873/Art_Arroz_TemporadayPerspectivas.pdf (2022).

Show, K. Y., Tay, J. H. & Lee, D. J. Cement Replacement Materials: Properties, Durability, Sustainability (Springer Berlin, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-36721-2

Espinoza, Á. & Farías, C. La cadena del arroz en Chile. Oficina De Estudios Y Políticas Agrarias (Odepa). https://www.odepa.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ARROZ2018Final.pdf (2017).

Hany, E., Fouad, N., Abdel-Wahab, M. & Sadek, E. Investigating the mechanical and thermal properties of compressed earth bricks made by eco-friendly stabilization materials as partial or full replacement of cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 281, 122535 (2021).

Morla, P., Gupta, R., Azarsa, P. & Sharma, A. Corrosion evaluation of geopolymer concrete made with fly ash and bottom ash. Sustain. (Switzerland). 13, 1–16 (2021).

Crossin, E. The greenhouse gas implications of using ground granulated blast furnace slag as a cement substitute. J. Clean. Prod. 95, 101–108 (2015).

Yahyaee Nojoukambari, T., Sadrmomtazi, A. & Kohani Khoshkbijari, R. Influence of feldspar and ground granulated blast-furnace slag as a partial cement replacement on mechanical properties and thermal durability and environmental impacts of cement mortars. J. Clean. Prod. 398, 136074 (2023).

Iqtidar, A. et al. Prediction of compressive strength of rice husk ash concrete through different machine learning processes. Cryst. (Basel) 11, 352 (2021).

Paul, S., Mortoza, G. & Chakraborty, P. Effectiveness of various supplementary cementitious materials in soil stabilization: a review. 7th International Conference on Advances in Civil Engineering (ICACE2024) (2024). https://icace2024.cuet.ac.bd

Onyelowe, K. C., Onyia, M. E., Van, D. B., Baykara, H. & Ugwu, H. U. Pozzolanic reaction in clayey soils for stabilization purposes: A classical overview of sustainable transport geotechnics. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2021, 6632171 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6632171 (2021).

Suksiripattanapong, C. et al. Use of cement and bottom ash in deep mixing application for stabilization of soft Bangkok clay. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48, 4583–4593 (2023).

Jain, A., Choudhary, A. K. & Jha, J. N. Influence of rice husk ash on the swelling and strength characteristics of expansive soil. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 38, 2293–2302 (2020).

Sambre, T., Endait, M. & Patil, S. Sustainable soil stabilization of expansive soil subgrades through lime-fly ash admixture. Discover Civil Eng. 1, 65 (2024).

Elahi, T. E., Shahriar, A. R., Alam, M. K. & Abedin, M. Z. Effectiveness of saw dust ash and cement for fabrication of compressed stabilized earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 259, 120568 (2020).

da Silva Milani, A. P., Labaki, L. C. Physical, mechanical, and thermal performance of cement-stabilized rammed earth–rice husk ash walls. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 24, 775–782 (2012).

Fapohunda, C., Akinbile, B. & Shittu, A. Structure and properties of mortar and concrete with rice husk ash as partial replacement of ordinary Portland cement – A review. Int. J. Sustainable Built Environ. 6, 675–692 (2017).

Preethi, R. K. & Venkatarama Reddy, B. V. Experimental investigations on geopolymer stabilised compressed earth products. Constr. Build. Mater. 257, 119563 (2020).

Singh, S., Chohan, J. S., Kumar, R. & Gupta, P. K. Stability of compressed earth blocks using sugarcane bagasse ash and wheat straw. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.07.023 (2021).

Chaibeddra, S. & Kharchi, F. Performance of compressed stabilized earth blocks in sulphated medium. J. Building Eng. 25, 100814 (2019).

Idriss, E. et al. Engineering and structural properties of compressed earth blocks (CEB) stabilized with a calcined clay-based alkali-activated binder. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions. 7, 1–9 (2022).

Poullain, P., Leklou, N., BabatoundéLaibi, A. & Gomina, M. Properties of compressed earth blocks made of traditional materials from Benin. Rev. Compos. Mater. Av. 29, 233–241 (2019).

Abessolo, D., Biwole, A. B., Fokwa, D., Ganou Koungang, B. M. & Yembe, B. Baah. Physical, mechanical and hygroscopic behaviour of compressed earth blocks stabilized with cement and reinforced with bamboo fibres. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. https://doi.org/10.4028/p-spbskv (2022).

Turco, C. et al. Influence of particle size on compressed earth blocks properties and strategies for enhanced performance. Appl. Sci. (Switzerland) 14, 1779 (2024).

Jayasinghe, C. & Mallawaarachchi, R. S. Flexural strength of compressed stabilized earth masonry materials. Mater. Des. 30, 3859–3868 (2009).

Sekhar, C., Nayak, S. & D. & Utilization of granulated blast furnace slag and cement in the manufacture of compressed stabilized earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 166, 531–536 (2018).

Muntohar, A. S. Engineering characteristics of the compressed-stabilized earth brick. Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 4215–4220 (2011).

Verma, A. & Sharma, T. Experimental study of the strength aspects of compressed stabilized Earth blocks using marble dust, sugarcane bagasse ash and paddy straw fiber. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 889, 012025 (2021).

Asha, P., Johnson, K., Sachin, C. M., Vetrivel, V. & Prasanna, E. Performance of compressed stabilised Earth blocks with rice husk ash. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 39, 143–153 (2020).

Nshimiyimana, P., Messan, A. & Courard, L. Hydric and durability performances of compressed Earth blocks stabilized with industrial and agro By-Product binders: calcium carbide residue and rice husk ash. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)mt.1943-5533.0003745 (2021).

Gibson, I., Rosen, D. & Stucker, B. Additive Manufacturing Technologies: 3D Printing, Rapid Prototyping, and Direct Digital Manufacturing. Springer Series in Advanced Manufacturing (Springer New York, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2113-3

Tuninetti, V. et al. Miniaturized shear testing: in-plane and through-thickness characterization of plywood. Materials 17, 5621 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17225621

Instituto Nacional de Normalización. NCh1017.Of1975 - Hormigón - Confección y curado en obra de probetas para ensayos de compresión y tracción. 1–15. (1975).

Rilling, S. et al. Optimized infill density through topological optimization increases strength of additively manufactured porous polylactic acid. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 129, 3739–3750 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-023-12554-z

Bendsøe, M. P. & Sigmund, O. Topology Optimization: Theory, Methods and Applications (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-05086-6

Ministerio de Agricultura. Comuna de Cauquenes - Recursos Naturales. Ciren (2020). http://www.sitrural.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Corral_rec_nat_1.pdf

SEREMI de Vivienda y Urbanismo - Región del Maule. Memoria Anteproyecto: Plan Regulador Intercomunal De Cauquenes. (2024). https://www.minvu.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Memoria-Anteproyecto-PRI-Cauquenes-.pdf

Bamgbopa, O. S. Investigation of Shrinkage and Cracking in Clay Soils under Wetting and Drying Cycles. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 5, 283-320 (2016). https://www.ijert.org/research/investigation-of-shrinkage-and-cracking-in-clay-soils-under-wetting-and-drying-cycles-IJERTV5IS110183.pdf

Andrade, F. A., Al-Qureshi, H. A. & Hotza, D. Measuring the plasticity of clays: A review. Applied Clay Science 51, 1–7 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2010.10.028

Nshimiyimana, P., Messan, A., Zhao, Z. & Courard, L. Chemico-microstructural changes in earthen building materials containing calcium carbide residue and rice husk ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 216, 622–631 (2019).

Nshimiyimana, P., Miraucourt, D., Messan, A. & Courard, L. Calcium carbide residue and rice husk ash for improving the compressive strength of compressed Earth blocks. MRS Adv. 3, 2009–2014 (2018).

Talibi, S., Page, J., Djelal, C., Waqif, M. & Saâdi, L. Study of earth-based materials for manufacturing compaction process. J. Building Eng. 64, 105546 (2023).

Boubekeur, S. & Houben, H. (eds) (CDI) (CRATerre/EAG). Compressed earth blocks: standards - technology series. (Centre pour le développement industriel (CDI) and the Center for the Research and Application of Earth Architecture (CRATerre-EAG)/Overseas Development Administration (ODA), Brussels, (1998).

Donkor, P. & Obonyo, E. Earthen construction materials: assessing the feasibility of improving strength and deformability of compressed earth blocks using polypropylene fibers. Mater. Des. 83, 813–819 (2015).

Walker, R. & Pavía, S. Physical properties and reactivity of pozzolans, and their influence on the properties of lime–pozzolan pastes. Mater. Struct. 44, 1139–1150 (2011).

Danso, H., Martinson, D. B., Ali, M. & Williams, J. B. Physical, mechanical and durability properties of soil building blocks reinforced with natural fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 101, 797–809 (2015).

Ben Mansour, M., Ogam, E., Jelidi, A., Cherif, A. S. & Ben Jabrallah Influence of compaction pressure on the mechanical and acoustic properties of compacted earth blocks: an inverse multi-parameter acoustic problem. Appl. Acoust. 125, 128–135 (2017).

González-López, J. R., Juárez-Alvarado, C. A., Ayub-Francis, B. & Mendoza-Rangel, J. M. Compaction effect on the compressive strength and durability of stabilized earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 163, 179–188 (2018).

Yi, S. T., Yang, E. I. & Choi, J. C. Effect of specimen sizes, specimen shapes, and placement directions on compressive strength of concrete. Nucl. Eng. Des. 236, 115–127 (2006).

Instron. 3360 Series Dual Column Tabletop Models: Specifications. (2018).

Tuninetti, V. et al. Experimental characterization of the compressive mechanical behaviour of Ti6Al4V alloy at constant strain rates over the full elastoplastic range. Int.J. Mater. Form. 13, 709–724 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-020-01543-2

Tuninetti, V., Gilles, G., Péron-Lührs, V. & Habraken, A. M. Compression test for metal characterization using digital image correlation and inverse modeling. Procedia IUTAM. 4, 206–214 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.piutam.2012.05.022

Tuninetti, V., Gilles, G., Milis, O., Lecarme, L. & Habraken, A. M. Compression test for plastic anisotropy characterization using optical full-field displacement measurement technique. Steel Res. Int. (special issue) 1239–1242 (2012).

Hwang, C. L., Yehualaw, M. D. & Huynh, T. P. Development of compressed stabilized earth block as an eco-friendly and sustainable wall making material. Int. J. Struct. Civil Eng. Res. 233–237. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijscer.7.3.233-237 (2018).

Yatawara, M. & Athukorala, S. Potential of replacing clay soil by rice husk ash (RHA) in enhancing the properties of compressed earth blocks (CEBs). Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 3474–3486 (2021).

Jannat, N., Hussien, A., Abdullah, B. & Cotgrave, A. Application of agro and non-agro waste materials for unfired earth blocks construction: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 254, 119346 (2020).

Nnamdi, E. N., Okwu-Delunzu, V. U. & Ezemerihe, A. Cost-benefit analysis of using stabilized-earth block to conventional block use in housing construction. Iconic Res. Eng. Journals. 5, 341–348 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Properties of sustainable earth construction materials: A State-of-the-Art review. Sustain. (Switzerland) 16, 670 (2024).

Adegun, O. B. & Adedeji, Y. M. D. Review of economic and environmental benefits of earthen materials for housing in Africa. Front. Architectural Res. 6, 519–528 (2017).

Bildirici, M. E. & Ersin, Ö. Ö. Cement production and CO2 emission cycles in the USA: evidence from MS-ARDL and MS-VARDL causality methods with century-long data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 35369–35395 (2024).

Cheng, D. et al. Projecting future carbon emissions from cement production in developing countries. Nat. Commun. 14, 8213 (2023).

Ro, J. W., Cunningham, P. R., Miller, S. A., Kendall, A. & Harvey, J. Technical, economic, and environmental feasibility of rice hull ash from electricity generation as a mineral additive to concrete. Sci. Rep. 14, 9158 (2024).

Indumathi, M., Nakkeeran, G., Roy, D., Gupta, S. K. & Alaneme, G. U. Innovative approaches to sustainable construction: a detailed study of rice husk ash as an eco-friendly substitute in cement production. Discover Appl. Sci. Vol. 6 https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-024-06314-1 (2024).

Rigon, M. R. et al. M. Revista AIDIS de Ingeniería y Ciencias Ambientales. Investigación, desarrollo y práctica 14, 246 (2021).

Locke, J., Dsilva, J. & Zarmukhambetova, S. Decarbonization strategies in the UAE built environment: an Evidence-Based analysis using COP26 and COP27 recommendations. Sustain. (Switzerland). 15, 1–21 (2023).

Bustillo Revuelta, M. Construction and demolition waste. In Construction Materials: Geology, Production and Applications 565–585 (Springer International Publishing, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65207-4_19.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo of Chile (ANID), Doctorado Nacional grant number 21222107 and Fondequip EQM180111. Prof. Tuninetti acknowledges the international cooperation research project WBI/AGCID RI02 (DIE23-0001) between the University of Liège and the Universidad de La Frontera.

Funding

This research was funded by Doctoral Grant 21222107 from the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo of Chile (ANID), grant number 21222107.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V. and V.T.; methodology, M.V., V.T., G.C.; formal analysis, M.V.; investigation, M.V.; resources, V.T.; data curation, M.V.; writing-original draft preparation, M.V., V.T.; writing-review and editing, M.V., V.T., A.M., G.C., A.O.; visualization, M.V., A.M.; validation, M.V.; supervision, V.T.; project administration, M.V., V.T.; funding acquisition, M.V., G.C., V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions