Abstract

Thailand experiencing severe air pollution for over a decade. Although the physical and chemical properties of particulate matter have been extensively studied, the biological aspects, particularly microorganisms present in fine particles during haze and non-haze periods, are still unclear. To address this gap, we aim to profile the bacterial communities in PM2.5 in Bangkok and Chiang Mai, Thailand. The samples were collected during the haze and non-haze periods in 2021–2022. Using 16 S rRNA gene sequencing, we identified a markedly higher number of bacterial genera in Chiang Mai (247) compared to Bangkok (31). In Bangkok, Actinobacteriota (80.4%) and Proteobacteria (18.3%) dominated, whereas Chiang Mai’s samples were enriched with Firmicutes (52.2%) and Bacteroidota (13.0%). Interestingly, Bangkok’s samples were dominated by Cutibacterium (68.4%) and Enhydrobacter (14.6%), while Chiang Mai had Bacillus (11.0%) and Blautia (7.6%). Despite substantially higher PM2.5 levels during haze, alpha diversity analyses showed that bacterial community structure was more strongly influenced by geographic location than by haze conditions. Chiang Mai consistently exhibited greater microbial richness and evenness than Bangkok. These findings highlight the importance of biological factors in urban air pollution studies and underscore the need to incorporate the biological aspects into health risk assessments and air quality management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution is a growing concern worldwide, with Thailand experiencing severe air pollution for over a decade. Critical pollutants impacting human health, as indicated by numerous studies, include particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and ozone (O3)1,2,3,4,5,6. Air pollutants, particularly fine particulate matter (PM2.5), are associated with increased human morbidity and mortality, and are known to contribute to a reduced life expectancy7. PM2.5 can penetrate down to the alveoli, and can translocate deeply into the circulation system8,9. There is substantial evidence connecting air pollution to diseases affecting the respiratory, circulatory, and nervous systems. Common diseases related to air pollution include allergic rhinitis, asthma, cerebrovascular diseases, stroke, cardiovascular diseases, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cancer1,10,11.

Haze periods in Thailand are primarily prevalent in the northern regions and typically occur during the dry season, from January to May. These periods are characterized by reduced visibility and poor air quality due to high concentrations of particulate matter4. The primary causes of these haze periods are agricultural burning, forest fires, and emissions from traffic and industrial activities12. The frequency and intensity of these periods are influenced by weather patterns, with drought conditions often exacerbating the situation13. In Thailand, airborne particles have been thoroughly studied in terms of types, sources, components, characteristics, and their effects on ecosystems and human health.

One important aspect of air pollution is that it may contain biological particles, such as microorganisms, fragments of organisms, and products derived from organisms14,15. It has been indicated that biological particles (bioaerosols) may account for approximately 25% of atmospheric aerosols16. Meanwhile, several studies have reported the relationships between air pollution and airborne microbial communities. For example, previous studies showed that high concentrations of particulate matter are associated with the complex microbial communities17,18,19,20,21. Furthermore, studies reported relationships between air pollution (haze and smog) and airborne microbial communities in China21,22 and a relationship between dust storm and airborne microbial communities in Korea23. Microorganisms present in PM2.5 are recognized as potential causes of various health symptoms and diseases24,25. However, to fully understand the health effects of air pollution in relation to biological particles, more detailed evidence, including elucidation of microbial communities, is needed.

In Thailand, particulate matter has become a critical issue, especially in the Bangkok and Chiang Mai. While the physical and chemical properties of particulate matter and emission sources are well-studied, the biological aspects, particularly microorganisms present in the inhalable fraction during haze periods, are less recognized. This gap indicates a need for in-depth research on airborne biological particles. Here, we aimed to investigate airborne bacterial community profiles in PM2.5 collected from Bangkok and Chiang Mai during both the dry-season haze period and the wet-season non-haze period in 2021.

Results

General characteristics of particulate matter during haze and non-haze periods

The study analyzed PM2.5 concentration levels in 18 samples from Bangkok and Chiang Mai during both haze and non-haze periods. During haze periods, PM2.5 levels in Chiang Mai ranged from 69.5 to 95.5 µg/m³, whereas in Bangkok they ranged from 52.7 to 66.2 µg/m³ (Fig. 1). The average daily PM2.5 concentrations were 60.6 ± 5.3 µg/m³ in Bangkok and 83.4 ± 10.8 µg/m³ in Chiang Mai (Table S1). Conversely, during non-haze periods, PM2.5 levels in Bangkok ranged from 16.9 to 25.4 µg/m³ and in Chiang Mai from 20.2 to 26.8 µg/m³. The daily averages were 21.9 ± 3.1 µg/m³ for Bangkok and 23.2 ± 3.5 µg/m³ for Chiang Mai. Notably, PM2.5 concentrations were roughly three times higher during haze periods compared to non-haze periods in both cities. Thailand’s Pollution Control Department (PCD) selected its PM2.5 standard based on both international guidelines (WHO) and local evidence showing the health risks from prolonged PM2.5 exposure. The older 24-hour standard of 50 µg/m³ was subsequently updated to 37.5 µg/m³ to better protect public health. Analysis showed that during haze periods, all samples exceeded these standards, whereas during non-haze periods, PM2.5 concentrations were within the acceptable range for all samples.

Taxonomic composition and relative abundance of airborne Bacteria in PM2.5

We identified 25 bacterial phyla, 56 classes, 110 orders, 157 families, and 247 genera in the eight Chiang Mai samples, whereas only 6 phyla, 9 classes, 22 orders, 26 families, and 31 genera were detected in the ten Bangkok samples. In the analysis of Bangkok samples, six bacterial phyla were identified, as shown in Fig. 2a. The five most prevalent bacterial phyla observed during both periods were Actinobacteriota (80.4%), followed by Proteobacteria (18.3%), Acidobacteriota (0.6%), Chloroflexi (0.5%), Firmicutes (0.1%), and Planctomycetota (0.1%). The results of the airborne bacterial community composition in Chiang Mai revealed a predominance of Firmicutes (52.2%), followed by Bacteroidota (13.0%), Actinobacteriota (11.1%), Proteobacteria (9.4%), and Chloroflexi (5.7%). Firmicutes was the most abundant phylum across all samples, with consistent presence of Actinobacteriota, as shown in Fig. 2b.

At genus level, the bacterial genera community during haze and non-haze periods in Bangkok is shown as Fig. 3a. Cutibacterium was the most dominant genus, constituting an average of 68.4% of the bacterial population, with its presence varying between 0.1% and 99.9%. Enhydrobacter followed as the second most prevalent genus, with an average relative abundance of 14.6%. Cutibacterium showed significantly higher abundance during haze conditions (91.56%) compared to non-haze conditions (45.28%). The most community of bacterial genera during haze and non-haze in Chiang Mai is shown in Fig. 3b. Among them, Bacillus from the Firmicutes phylum was the most prominent, with a relative abundance of 11.0%, and Blautia followed with 7.6%. In the Bacteroidota phylum, the genera Prevotella and Bacteroides were the most abundant, with relative abundances of 5.1% and 3.4%, respectively. Interestingly, Bacillus exhibited the highest abundance in both haze and non-haze periods (Table S2). Lactobacillus showed a higher relative abundance in haze (2.57%) than in non-haze (0.70%). Conversely, Blautia had a significantly higher presence in non-haze (11.66%) compared to haze (3.53%). Prevotella was also more abundant in non-haze (7.74%) than in haze (2.48%).

The study found that the pathogenic genus Mycobacterium had a relative abundance of 0.35% in Chiang Mai and 0.01% in Bangkok. Corynebacterium, which is commonly found in soil and on the skin and mucous membranes of humans and animals, was present at 0.13% in Chiang Mai and 4.73% in Bangkok. Additionally, the gram-negative bacterium Klebsiella was detected at a low concentration of 0.13% in Chiang Mai. Other pathogens were also documented; Streptococcus, Helicobacter and Prevotella were exclusively identified in Chiang Mai samples, while Legionella was found in Bangkok at a low abundance of 0.03%.

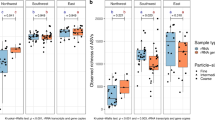

Diversity in airborne bacterial communities

A total of 295,560 with 29,556 reads per sample were obtained after excluding non-qualified gene sequences from Bangkok, while Chiang Mai showed 178,176 with 22,272 reads per sample. These reads were subsequently subsampled and categorized 75 distinct operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for Bangkok and 639 OTUs for Chiang Mai. The number of OTUs per sample ranged from 4 to 32 in Bangkok and 17 to 273 in Chiang Mai. The rarefaction curves indicated that high throughput sequencing effectively captured the dominant phylotypes in the microbial community structures of both Bangkok (Fig. S1) and Chiang Mai samples (Fig. S2). The correlation analysis between PM2.5 concentration and bacterial communities revealed no statistically significant association in either Bangkok (r = 0.092, p-value = 0.799) or Chiang Mai (r=-0.409, p-value = 0.315). Alpha diversity within each sample was evaluated using measures including Chao1, Shannon and Simpson indices. These indices were used to compare community diversity in different samples. Notably, the non-haze period exhibited higher values for the Chao1, Shannon indices and Simpson compared to haze periods among both Bangkok and Chiang Mai (Table S3). However, there was no statistically significant difference between the bacterial community diversity and different haze level (Mann–Whitney U test: p-value > 0.05). This study highlighted notable differences in alpha diversity of bacterial communities between two geographically distinct locations: Bangkok and Chiang Mai (Fig. 4). The Chao1 index showed significantly higher species richness in Chiang Mai, with an average of 129.7 ± 105.8, compared to Bangkok’s average of 13.2 ± 9.9 (p-value < 0.05). Similarly, the Shannon index revealed greater bacterial diversity in Chiang Mai, averaging 5.6 ± 1.9, while Bangkok averaged 1.3 ± 1.1 (p-value < 0.05). Additionally, the Simpson index indicated a higher probability of interspecies encounters in Chiang Mai, with an average of 0.9 ± 0.2, compared to 0.4 ± 0.3 in Bangkok (p-value < 0.05).

Airborne bacterial communities with different haze levels

The variation of bacterial communities in PM2.5 collected from Bangkok and Chiang Mai during different haze periods was analyzed using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). This analysis revealed the similarity of microbial communities between both sampling periods at each location. The PCoA result based on the Bray-Curtis distance matrix reveals the bacterial community compositions across different samples from Bangkok and Chiang Mai under haze and non-haze periods (Fig. 5).

Interestingly, the PCoA findings revealed distinct clusters based on geographic location for bacterial compositions in samples from Bangkok and Chiang Mai, indicating that location significantly influences the overall microbial community composition. In Bangkok, a comparative analysis of bacterial community structures during haze and non-haze periods showed distinct clustering patterns. Non-haze samples displayed a wider spread, suggesting greater variability in microbial community composition. In contrast, haze samples exhibited tighter clustering with minimal dispersion along both principal axes (PCoA1 and PCoA2). The ANOSIM result (R = 0.267, p-value > 0.05) indicates a slight dissimilarity between bacterial communities during haze and non-haze periods. In Chiang Mai, bacterial compositions in haze samples showed greater dispersion, whereas non-haze samples clustered more closely together, indicating higher similarity within this group compared to haze period samples. The ANOSIM result (R = 0.0067, p-value > 0.05) suggests no statistically significant difference in bacterial communities between haze and non-haze periods. Furthermore, the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) revealed that there are no bacterial taxa with a log LDA score greater than 2. Similarly, the Benjamini-Hochberg test indicated that no bacterial taxa exhibited a significant difference between haze levels (q > 0.05). These findings suggest that no bacterial taxa showed significantly different abundances between the haze and non-haze periods.

Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the composition and diversity of airborne bacterial communities in PM2.5 collected from Bangkok and Chiang Mai during both haze and non-haze periods. While PM2.5 concentrations were significantly higher during haze periods, these elevated levels result from multiple interacting factors. For example, stable atmospheric layers, limited rainfall, and low wind speeds can trap pollutants near the ground, leading to an accumulation of particulate matter during the dry season26. Agricultural burning, forest fires, and biomass combustion are common in Northern Thailand during the dry season27,28. These activities release large amounts of particulate matter into the atmosphere. In Bangkok, heavy traffic congestion and industrial emissions can further exacerbate PM2.5 levels, especially when atmospheric dispersion is poor during dry season29,30.

According to the several studies, the biological components in PM2.5 can cause human health effects, particularly respiratory syndromes15,24,25,31. In this study, we have explored the significant variances in PM2.5 concentrations and the composition of airborne bacterial communities during haze and non-haze periods in Bangkok and Chiang Mai, Thailand. Currently, there are several studies that have characterized the abundance and community composition of airborne microbes in both indoor and outdoor environments around the world17,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Many of these studies aim to profile the microbial community and demonstrate the relationship between particulate matter and the airborne microbiome. In Southeast Asia, the exploration of airborne microbial communities through microbiome approaches remains limited40,41,42,43, with all studies have predominantly focused on characterizing indoor microbiomes. However, studies conducted in Singapore have demonstrated the presence of an airborne microbial community characterized by low biomass in tropical aerial ecosystems44,45,46,47. These studies highlight the role of atmospheric conditions in shaping the composition and distribution of airborne microorganisms.

Taxonomic composition of airborne bacterial community showed a variation in the relative abundance in different haze levels. In both periods of Bangkok and Chiang Mai, the five predominant bacterial phyla observed were Actinobacteriota, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, and Chloroflexi. Significantly, Actinobacteriota and Firmicutes were the only phyla consistently detected in all atmospheric conditions in Chiang Mai, whereas in Bangkok, only Actinobacteriota were found in all samples. These bacterial phyla were also characterized in the previous studies22,37,47,48. The significant presence of these bacterial phyla suggests their resistance to pollutants, aligning with previous studies that have identified similar groups in soil microbes49,50,51. These studies noted their ability to resist heavy metals and various organic compounds in the soil. The presence of PAHs and metals significantly influences the structure of microbial communities, leading to the emergence of species resistant to pollution52,53,54. Additionally, the composition of particulate matter in Bangkok and Chiang Mai revealed the presence of several toxic chemical components, including heavy metals and PAHs55,56,57.

This study revealed variations in the number of bacterial genera between haze and non-haze samples in both Bangkok and Chiang Mai, with higher diversity observed during the non-haze period compared to the haze period. Our findings characterized the dominant airborne bacterial genera in Chiang Mai as Bacillus, Blautia, Prevotella and Bacteroides, while Cutibacterium and Enhydrobacter emerged as the predominant genus in Bangkok. This study demonstrated the distinct composition of bacterial communities in PM2.5 samples under different environmental conditions. The bacterial community observed in this study highlighted significant genera, consistent with findings from previous studies22,36,58. The study on bacterial diversity in the subway environment of Bangkok, Thailand revealed that the dominant bacterial genera were Acinetobacter, Moraxella, Sphingomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Paracoccus, Corynebacterium, Pseudomonas, and Kocuria. The predominance of human skin-associated bacteria, Cutibacterium, found in our study aligns with a previous study in Thailand, which described these bacteria as prevalent in various environments43.

The potential pathogenic bacteria found in this study are similar to the previous study24,25,34,38,39. The results revealed the predominant pathogenic bacteria in the different seasons and areas. This study identified the presence of several bacterial genera, including Mycobacterium, Corynebacterium, Bacillus, Helicobacter, Streptococcus, and Prevotella. Our findings showed an overall greater abundance of pathogenic bacteria during non-haze periods in comparison to haze periods. The health impacts of PM2.5 may arise not only from its chemical compositions but also potentially from the biological components. In addition to the direct health impacts cause by pathogens, components of airborne microbes (e.g. endotoxins, mycotoxins, and glucans) can also significantly affect human health31. Although the mere presence of these taxa does not confirm their viability or infectivity, our results provide a foundational assessment of the bacterial load within PM2.5. This is particularly relevant when considering epidemiological links between air pollution and respiratory diseases. For instance, Pongpiachan and Paowa (2015) reported that hospital admissions in Chiang Mai are associated with variations in trace gaseous pollutants, suggesting that changes in air quality can affect public health outcomes59.

In Bangkok and Chiang Mai, the diversity of bacterial communities shows no statistically significant difference between haze and non-haze periods. These findings indicate that the variety and distribution of species within each location are similar during both haze periods. Our findings align with the previous studies, indicating that haze levels did not significantly impact the composition of airborne bacterial communities. There were no significant differences in the dominant bacterial genus between haze and non-haze days22,36,38. These suggest that the level of haze—whether low or high—does not have a significant impact on the diversity of the bacterial community. The diversity, in terms of species richness and evenness, remains relatively constant regardless of the haze conditions. The similarity in environmental conditions can be a key factor in comparable species diversity across different habitats. Furthermore, the variation of bacteria community structure depending on several environmental factors including NO2, SO2, and O3 as revealed in the previous studies34,36. The lack of observed differences of bacterial community could be attributed to the sample size or the extent of the sampling effort, which might not be sufficient to detect existing variations. The study concluded that there was no statistically significant difference in alpha diversity between haze and non-haze days, even though non-haze days appeared to have higher diversity. This raises the concern of whether the number of collected samples was adequate to reliably detect statistical significance. A smaller sample size might not adequately represent the bacterial diversity, potentially leading to an inability to detect true differences in diversity levels between conditions. Additionally, the sample collection method could influence the correlation between bacterial community composition and haze levels. Variations in air samplers and flow rates can impact the yield of microbial communities collected from the air. The sampling duration is another key factor contributing to the nonsignificant findings in this study. As described in prior experiments on ultra-low biomass bioaerosol analysis, factors such as flow rate, sampling duration, storage, extraction, and analysis approach pose challenges in studying airborne bioaerosols47.

The findings underscore the need to examine how environmental parameters shape microbial communities in urban atmospheres, particularly in densely populated tropical regions. In addition to traditional air pollutants, recent evidence has highlighted the role of meteorological factors in affecting pathogen transmission. For example, Pongpiachan et al. (2024) demonstrated that parameters like temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed can significantly influence COVID-19 transmission in Thailand60. Although our study focuses on bacterial communities rather than viral pathogens, these findings reinforce the broader concept that meteorological conditions and aerosol dynamics play a crucial role in the persistence and dispersal of airborne microorganisms.

Although there were no significant differences in bacterial communities between haze and non-haze periods in both locations, the non-haze periods showed slightly higher diversity than the haze periods. This observation is consistent with previous studies that reported higher bacterial abundance in PM2.5 during non-haze periods compared to haze periods61,62. The study on airborne PM-associated bacteria in Hangzhou, China, revealed that both the abundance and diversity of bacteria were at their lowest in air that was moderately or heavily polluted62. Moreover, the study of airborne bacteria reported that the concentrations of airborne bacteria were lower on hazy days61. The findings of higher bacterial diversity in non-haze periods compared to haze periods align with previous research on the pulmonary toxicity of particulate matter from Chiang Mai15. Notably, that study reported higher bacterial endotoxin concentrations in non-haze particulate matter than in haze conditions. The higher endotoxin content in non-haze PM reflects a greater presence of bacterial fragments, which may explain the more pronounced inflammatory response observed in the study. This biological component of Chiang Mai’s particulate matter could explain our observations. Additionally, their results indicating greater toxicity to human cells of non-haze particulate matter might be attributed to the higher bacterial diversity observed in non-haze periods.

The diversity of airborne bacteria decreased as the PM2.5 concentration increased, suggesting that polluted air may have a damaging effect on total bacteria63. Previous studies indicated that although pollutants on hazy days provide more nutrients (such as sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium) supporting bacterial metabolism, they also contribute to greater bacterial cell damage and death than on non-hazy days64,65. This suggests that PM levels during haze periods have higher toxicity than those during non-haze periods due to the presence of PAHs and heavy metals, which can harm bacterial cells. PM2.5 particles presented in Thailand carry toxic substances, including heavy metals, PAHs, and organic pollutants, which can inhibit bacterial growth or cause cell death6,66. Furthermore, studies conducted in Northern Thailand have revealed that the toxicity levels of PM2.5 are notably higher during haze periods compared to non-haze periods6,66,67. In general, PM2.5 and its chemical components are known to affect cell viability, potentially causing oxidative damage and inflammatory effects68. The previous studies had revealed the effects of heavy metal and PAHs in the microbial community structure69,70. The exposure to these toxic compounds can inhibit bacterial growth or even lead to cell death. The toxicity of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and its impact on microbial viability is a complex topic, mainly due to the diverse sources and compositions of PM2.5. This evidence supports the observation of a higher bacterial abundance during non-haze periods compared to haze periods in this study.

However, there were significant differences of bacterial diversity (richness and evenness) between two distinct locations, Bangkok, and Chiang Mai in this study. Collectively, these findings significantly highlight the contrasts in bacterial alpha diversity between Bangkok and Chiang Mai. The influence of geographical location on the significant variations in airborne bacterial communities has also been documented in a prior study, which compared three cities across China, South Korea, and Japan71. The marked differences in species richness, evenness, and dominance suggest that environmental factors, habitat diversity, and possibly human activity levels may be influencing the bacterial ecosystems differently in the two locations. Contrasting effects have been described by previous studies, which have uncovered the impact of anthropogenic activities on the higher diversity of airborne bacteria72.

The results of beta diversity revealed that samples from Bangkok under non-haze conditions show a wider spread in the plot, indicating more variability in bacterial community composition compared to haze conditions. This could suggest that non-haze conditions do not constrain bacterial diversity to the same extent as haze periods. Chiang Mai samples show distinct separation between haze and non-haze conditions, with some non-haze samples clustering closer together, implying a transitional bacterial community composition between the extreme conditions observed in Chiang Mai haze and non-haze samples. There appears to be a distinct clustering pattern based on location, with samples from Bangkok clustering separately from those of Chiang Mai. This suggests that the overall bacterial community composition is significantly influenced by geographic location, which could be due to a variety of environmental, climatic, or human-activity related factors unique to each location. These findings align with the alpha diversity metrics, which revealed significant differences in bacterial diversity (both in terms of richness and evenness) between the two distinct locations, Bangkok, and Chiang Mai. Samples collected under haze conditions in both Bangkok and Chiang Mai tend to be positioned similarly their non-haze counterparts, suggesting that haze does not have a consistent effect on microbial communities across these locations.

Based on the results of bacterial community profiles from PM2.5 during haze and non-haze periods in Bangkok and Chiang Mai in this study. The study focuses on fine particles (PM2.5) without considering different size fractions of particulate matter. This limits the understanding of how different PM sizes may carry distinct microbial communities. The limited sample size may impact the statistical analysis and the generalizability of the findings, particularly in LEfSe analysis and the Benjamini-Hochberg test. A larger sample size would provide more robust data and enhance the reliability of the results. The study compares haze and non-haze periods but does not account for long-term temporal changes or seasonal variations beyond these periods. Including a broader temporal scope could help in identifying trends and patterns over time. While the study acknowledges variations in urbanization levels, climate, geography, and seasonal practices, it does not extensively explore how these environmental factors specifically influence bacterial community composition. A more detailed analysis of these factors could help in understanding their roles in shaping microbial diversity. In future research, a comparative analysis of particulate matter size fractions and various microbial communities could enhance our understanding of the association between airborne particles and microbial dynamics. Identifying the specific environmental, urbanization, and anthropogenic factors that influence these distinctions could pave the way for advances in biodiversity research. Studying bacteria that thrive under the extreme conditions of the haze period is essential for understanding potential health risks and ecological impacts. Recognizing these differences is crucial for addressing environmental health risks and developing targeted strategies for air quality management and disease prevention in various locations.

Conclusion

This study provides the first comprehensive investigation of airborne bacterial communities in PM2.5 from Bangkok and Chiang Mai, using DNA-based methodologies and high-throughput sequencing techniques, revealed that geographical location had a stronger influence on microbial composition than haze versus non-haze conditions. While PM2.5 concentrations were approximately three times higher during haze periods, bacterial diversity remained relatively stable across haze and non-haze samples. However, significant differences in taxonomic richness and evenness were observed between the two cities, with Bangkok’s samples predominantly enriched with Actinobacteriota (especially Cutibacterium), whereas Chiang Mai exhibited greater taxonomic richness and evenness, featuring Firmicutes and Bacteroidota as prevalent phyla. Beta diversity analysis further demonstrated distinct clustering patterns based on location, suggesting that variations in bacterial communities were likely driven by differences in urbanization levels, climate, geography, and seasonal practices rather than haze intensity alone. These findings underscore the importance of considering both local environmental factors (e.g., population density and emission sources) and meteorological conditions when evaluating airborne microbiomes in tropical urban areas. This study establishes a foundation for further research into how these bacterial variations influence air quality, human health, and ecosystem processes, particularly in regions affected by seasonal haze events.

Materials and methods

Sampling location

Bangkok and Chiang Mai are the selected sampling sites for the haze and non-haze periods (Fig. 6). These sites were selected to represent large economic cities that experience significant air pollution annually. In Bangkok, samples were collected at the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University (13°45’57"N, 100°32’01"E). This urban site is characterized by high-rise buildings surrounding the area. As the capital city of Thailand, Bangkok is located in the central part of the country, covering an area of approximately 1,569 km², and experiences heavy vehicular traffic and annual air pollution challenges. The sampling site in Chiang Mai Municipality (18°47’41.8"N, 98°59’56.3"E) is surrounded by office and commercial areas and is strategically located near the Mae Ping River, an important natural water source for the area. Chiang Mai province, located in the upper northern region of Thailand, is in a valley surrounded by high mountains. It is the second largest province in the country and the largest in northern Thailand, covering an area of approximately 52,077 km², and is about 740 km from Bangkok.

Locations of the air sample collection in Bangkok and Chiang Mai Provinces, Thailand (https://pixelmap.amcharts.com and Google Earth, 2024).

Sample collection

This study adapted previously described sampling methods to collect PM2.5 at ground level (1.5 m), mirroring typical human exposure conditions6,34,73. Sampling took place in March (haze period) and November (non-haze period), as summarized in Table S1. Using a Deployable Particulate Sampler (DPS) (SKC, Eighty-Four, PA, USA) at a flow rate of 10 L/min over 24 h, we collected PM2.5 on 47-mm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane filters (Pall, NY, USA) for mass determination and on quartz fiber filters (Pall, NY, USA) for microbiological analyses. To sterilize the filters, we rinsed PTFE membranes with acetone and kept them in a desiccator until their weight stabilized, while quartz fiber filters were autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min. Additionally, the filter holders were thoroughly cleaned with 75% ethanol, and all tools used in filter handling were autoclaved to prevent contamination. Immediately after sampling, filters were placed in sterile plastic plates, stored on ice for transport, and subsequently transferred to − 20 °C for preservation. Field blanks served as negative controls throughout the study, ensuring the reliability of our data.

Particulate matter analysis

Each air sample volume was 14.40 m³, and each filter was weighted to calculate the mass concentration. The concentrations of PM2.5 were determined using a gravimetric method using an ultra-microbalance with a readability of 0.1 µg (Sartorius MSU2.7 S-000-DF Cubis Ultra Micro Balance, IL, USA).

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

DNA was extracted using a DNeasy PowerSoil Pro DNA Kit (Qiagen, USA) and were amplified with a repliG Mini Kit (QIAGEN, USA) before 16S rRNA gene amplification. The V3-V4 region of bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 341F (5’-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3’) and 805R (5’-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3’) with X sparQ HiFi PCR master Mix (QuantaBio, USA). The amplification condition included a 2-min initial denaturation step at 98 C, followed by 30 cycles of 98 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, followed by a single step final extension step at 72 °C for 1 min. Field and laboratory filter blanks were employed to extract DNA, which were then undergo analysis. These components served as the negative control in the analysis of the microbial profile from air samples.

Illumina miseq sequencing

The 16 S rRNA gene amplicons were purified using sparQ Puremag Beads (QuantaBio, USA) and indexed using 5 µl of each Nextera XT index primer in a 50 µl PCR reaction, followed by 8–10 cycles of PCR condition above. The final PCR products were cleaned, pooled, and diluted to the final loading concentration at 4 pM. Cluster generation and 250-bp paired-end read sequencing were performed on an Illumina MiSeq at Omics Sciences and Bioinformatics Center (Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand). In the PCR analysis steps, negative controls (field and laboratory filter blanks) showed no fragments of 16 S rRNA genes. This indicates there was no artificial contamination, such as aerosol contamination during sampling and experimental procedures. The outcome of the sequencing data was uploaded into the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and archived under Bio-Project: PRJNA1102610 (Chiang Mai) and Bio-Project: PRJNA1102722 (Bangkok).

Sequencing data analysis

Microbiome bioinformatics analyses were conducted using QIIME 2 version 2022.11 74. The raw sequencing data underwent demultiplexing and quality filtering using the q2-demux plugin, followed by denoising with the DADA2 75. Sequencing data in the FASTq format were trimmed for quality, using the Phred parameter (score ≥ 39 into a sliding window composed of 4 bp) using Trimmomatic v0.32102 and truncated to a size of 165 bp76. For the phylogenetic analysis, the SEPP q2-plugin was employed to insert short sequences into the sepp-refs-gg-13-8.qza reference phylogenetic tree77. Alpha-diversity metrics assessed in this study included Chao1, Shannon indexes, Simpson78. In this study, OTUs were defined with 99% sequence similarity. For beta diversity, we evaluated metrics such as weighted UniFrac79, unweighted UniFrac80, and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity81. These metrics, along with Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA), were calculated using the q2-diversity plugin. The analyses were performed after normalizing the sample sizes, achieved by rarefying (subsampling without replacement) to a consistent depth of 22,272 (Chiang Mai) and 29,556 (Bangkok) reads per sample. The taxonomic classification of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) was conducted using the q2-feature-classifier plugin82. This process utilized the classify-sklearn naïve Bayes taxonomy classifier, which compared the sequences against the Silva 13_8 reference database.

Statistical analysis

The PM2.5 concentration was analyzed using descriptive statistics, specifically the mean and standard deviation. All samples were normalized at the same sequence depth (22,272 and 29,556 reads) for Chiang Mai and Bangkok, respectively. The OTUs with 99% similarity were used as a basis for calculating alpha diversity and beta diversity metrics. The R statistical computing environment was used for statistics and visualizations (version 4.3.2). The log-10 transformation of the bacterial relative abundance for all samples was computed and visualized in the form of a heatmap. Statistical comparisons of Chao1, Shannon and Simpson indices between two locations were made by Mann-Whitney U test. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the relationship between PM2.5 concentration and bacterial OTUs. Principal coordinate analyses (PCoA) based on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity distance matrix were conducted to check the difference in bacterial communities between two different periods. An analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) was performed to determine whether airborne bacterial communities are related to air pollution levels. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) was performed to determine bacterial taxa that differed significantly in abundance between haze and non-haze periods. A log linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score of > 2 was defined as the threshold for determining significantly different taxa17. Benjamini Hochberg test was conducted to analyze the multiple testing correction and control the false discovery rate (FDR) at q < 0.05. Statistical results were considered statistically significant at P value < 0.05.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in the paper and its Supplementary Information section.

References

Mueller, W. et al. Ambient particulate matter and biomass burning: an ecological time series study of respiratory and cardiovascular hospital visits in Northern Thailand. Environ. Heal Glob Access. Sci. Source. 19, 1–12 (2020).

Barletta, B. et al. Volatile organic compounds in 43 Chinese cities. Atmos. Environ. 39, 5979–5990 (2005).

Pascal, M. et al. A Review of the Epidemiological Methods Used to Investigate the Health Impacts of Air Pollution around Major Industrial Areas. J. ofEnvironmental Public Heal. (2013). (2013).

Kliengchuay, W. et al. Particulate matter (PM 10) prediction based on multiple linear regression: a case study in Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. BMC Public. Health. 21, 1–10 (2021).

Jenwitheesuk, K., Virasiri, S. & Jenwitheesuk, K. Chemical components of ambient particulate air pollution affecting suicides in Thailand. Emerg. Contam. 8, 304–309 (2022).

Kongpran, J., Kliengchuay, W. & Niampradit, S. The health risks of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): upper North Thailand geohealth. GeoHealth 5, 1–10 (2021).

Ezzati, M. & Dockery, D. W. Fine-Particulate Air Pollution and Life Expectancy in the United States. (2009).

Alves, N. D. O. et al. Biomass burning in the Amazon region causes DNA damage and cell death in human lung cells. 1–13 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11024-3

Valavanidis, A., Fiotakis, K. & Vlachogianni, T. Airborne particulate matter and human health: toxicological assessment and importance of size and composition of particles for oxidative damage and carcinogenic mechanisms. J. Environ. Sci. Heal Part. C Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 26, 339–362 (2008).

Genc, S., Zadeoglulari, Z., Fuss, S. H. & Genc, K. The Adverse Effects of Air Pollution on the Nervous System. J. ofToxicology (2012). (2012).

Mueller, W. et al. A health impact assessment of long-term exposure to particulate air pollution in Thailand. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 055018 (2021).

Phairuang, W., Hata, M. & Furuuchi, M. Influence of agricultural activities, forest fires and agro-industries on air quality in Thailand. J. Environ. Sci. 52, 85–97 (2017).

Sirithian, D. & Thanatrakolsri, P. Relationships between meteorological and particulate matter concentrations (PM 2. 5 and PM 10) during the haze period in urban and rural areas, Northern Thailand. Air Soil. Water Res. 15, 1–15 (2022).

Georgakopoulos, D. G. & Despr, V. Microbiology and atmospheric processes: biological, physical and chemical characterization of aerosol particles. Biogeosciences 6, 721–737 (2009).

Maciaszek, K. et al. In vitro assessment of the pulmonary toxicity of particulate matter emitted during haze events in Chiang Mai, Thailand via investigation of macrophage responses. Environ. Res. Heal. 1, 25002 (2023).

Jaenicke, R. Abundance of cellular material and proteins in the atmosphere. Sci. (80-). 308, 73 (2005).

Yan, D., Tao, Z., Yu, L. Y., Su;, J. & Yu, L. Y. Structural variation in the bacterial community associated with airborne particulate matter in Beijing, China, during hazy and nonhazy days. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, 1–13 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Concentration and community of airborne bacteria in response to cyclical haze events during the fall and midwinter in Beijing, China. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1–12 (2018).

Kaushik, R. & Balasubramanian, R. Assessment of bacterial pathogens in fresh rainwater and airborne particulate matter using Real-Time PCR. Atmos. Environ. 46, 131–139 (2012).

Cha, S. et al. Alterations in the airborne bacterial community during Asian dust events occurring between February and March 2015 in South Korea. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–9 (2016).

Cao, C. et al. Inhalable microorganisms in Beijing’s PM2.5 and PM10 pollutants during a severe smog event. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 1499–1507 (2014).

Lu, R. et al. Bacterial community structure in atmospheric particulate matters of different sizes during the haze days in Xi’an, China. Sci. Total Environ. 637–638, 244–252 (2018).

Oh, S. Y., Fong, J. J., Park, M. S., Chang, L. & Lim, Y. W. Identifying airborne fungi in Seoul, Korea using metagenomics. J. Microbiol. 52, 465–472 (2014).

Wu, B. et al. Pathological damage, immune-related protein expression, and oxidative stress in lungs of BALB/c mice induced by haze PM2.5 biological components exposure. Atmos. Environ. 223, 117230 (2020).

Zomuansangi, R. et al. Interaction of bacteria and inhalable particulate matter in respiratory infectious diseases caused by bacteria. Atmos. Pollut Res. 15, 102012 (2024).

Nguyen, G. T. H., Shimadera, H., Matsuo, T. & Kondo, A. Assessment of aerosol direct effects on PM2.5 and O3 air quality in continental Southeast Asia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 257, 012001 (2019).

Kayee, J. et al. Metal concentrations and source apportionment of PM2.5in Chiang Rai and Bangkok, Thailand during a biomass burning season. ACS Earth Sp Chem. 4, 1213–1226 (2020).

Duc, H. N., Bang, H. Q., Quan, N. H. & Quang, N. X. Impact of biomass burnings in Southeast Asia on air quality and pollutant transport during the end of the 2019 dry season. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 1–28 (2021).

Hung, N. T. Q. et al. Characterization of black carbon at roadside sites and along vehicle roadways in the Bangkok metropolitan region. Atmos. Environ. 92, 231–239 (2014).

Jareemit, D., Liu, J. & Srivanit, M. Modeling the effects of urban form on ventilation patterns and traffic-related PM2.5 pollution in a central business area of Bangkok. Build. Environ. 244, 110756 (2023).

Eduard, W., Heederik, D., Duchaine, C. & Green, B. J. Bioaerosol exposure assessment in the workplace: the past, present and recent advances. J. Environ. Monit. 14, 334–339 (2012).

Maloukh, L. et al. Metagenomic analysis of the outdoor dust microbiomes: A case study from Abu Dhabi, UAE. Atmos. (Basel). 14, 1–10 (2023).

Pollegioni, P. et al. Diversity and source of airborne microbial communities at differential polluted sites of Rome. Atmos. (Basel) 13, 224 (2022).

Rao, Y. et al. Characterization of airborne microbial aerosols during a long-range transported dust event in Eastern China: bacterial community, influencing factors, and potential health effects. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 20, 2834–2845 (2020).

Yan, D. et al. Diversity and composition of airborne fungal community associated with particulate matters in Beijing during haze and non-haze days. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1–12 (2016).

Xu, C. et al. Bacterial characterization in ambient submicron particles during severe haze episodes at Ji’nan, China. Sci. Total Environ. 580, 188–196 (2017).

Wei, M. et al. Characteristics of atmospheric bacterial and fungal communities in PM2.5 following biomass burning disturbance in a rural area of North China plain. Sci. Total Environ. 651, 2727–2739 (2019).

Du, P., Du, R., Ren, W., Lu, Z. & Fu, P. Seasonal variation characteristic of inhalable microbial communities in PM2.5 in Beijing City, China. Sci. Total Environ. 610–611, 308–315 (2018).

Du, P. et al. Variations of bacteria and fungi in PM2.5 in Beijing, China. Atmos. Environ. 172, 55–64 (2018).

Fu, X. et al. Associations between the indoor microbiome, environmental characteristics and respiratory infections in junior high school students of Johor Bahru, Malaysia. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts. 23, 1171–1181 (2021).

Fu, X. et al. Association between indoor Microbiome exposure and sick Building syndrome (SBS) in junior high schools of Johor Bahru, Malaysia. Sci. Total Environ. 753, 141904 (2021).

Fu, X. et al. Indoor microbiome, environmental characteristics and asthma among junior high school students in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. Environ. Int. 138, 105664 (2020).

Siriarchawatana, P. et al. Temporal, compositional, and functional differences in the Microbiome of Bangkok subway air environment. Environ. Res. 219, 115065 (2023).

Gusareva, E. S. et al. Microbial communities in the tropical air ecosystem follow a precise diel cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 23299–23308 (2019).

Drautz-moses, D. I., Luhung, I., Gusareva, E. S., Kee, C. & Gaultier, N. E. Vertical stratification of the air Microbiome in the lower troposphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, 1–8 (2022).

Gusareva, E. S. et al. Short-range contributions of local sources to ambient air. PNAS Nexus. 1, 1–10 (2022).

Luhung, I. et al. Experimental parameters defining ultra-low biomass bioaerosol analysis. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 7, 1–11 (2021).

Park, E. H., Heo, J., Kim, H. & Yi, S. M. The major chemical constituents of PM2.5 and airborne bacterial community phyla in Beijing, Seoul, and Nagasaki. Chemosphere 254, 126870 (2020).

Xu, Q., Qin, J., Yuan, T. & Ko, J. H. Extracellular enzyme and microbial activity in MSW landfills with different gas collection and leachate management practices. Chemosphere 250, 126264 (2020).

Liang, Y., Yin, Q., Jiang, Z., Yan, H. & Nian, Y. Pollution characteristics and microbial community succession of a rural informal landfill in an arid climate. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 262, 115295 (2023).

Meng, L. et al. Effects of different concentrations of Biochar amendments and Pb toxicity on rhizosphere soil characteristics and bacterial community of red clover (Trifolium pretense L). Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1–13 (2023).

Júlio, A. D. L., de Cássia Mourão Silva, U., Medeiros, J. D., Morais, D. K. & dos Santos, V. L. Metataxonomic analyses reveal differences in aquifer bacterial community as a function of creosote contamination and its potential for contaminant remediation. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–14 (2019).

Sazykin, I., Khmelevtsova, L., Azhogina, T. & Sazykina, M. Heavy metals influence on the bacterial community of soils: A review. Agric. 13, 653 (2023).

Vetrova, A. A. et al. Diversity of microbial communities, PAHs, and metals in road and leaf dust of functional zones of Moscow and Murmansk. Microorganisms 11, 1–18 (2023).

Chantara, S. PM10 and Its Chemical Composition: A Case Study in Chiang Mai, Thailand. in Air Quality - Monitoring and Modeling (eds. Kumar, S. & Kumar, R.)IntechOpen, (2012). https://doi.org/10.5772/33086

Chantara, S., Wangkarn, S., Tengcharoenkul, U., Sangchan, W. & Rayanakorn, M. Chemical analysis of airborne particulates for air pollutants in Chiang Mai and Lamphun provinces, Thailand. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 36, 123–135 (2009).

Somsunun, K. et al. Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Indoor Household Dust in Urban and Rural Areas of Chiang Mai and Lamphun Provinces, Thailand. Toxics 11, (2023).

Ruiz-Gil, T. et al. Airborne bacterial communities of outdoor environments and their associated influencing factors. Environ. Int. 145, 106156 (2020).

Pongpiachan, S. & Paowa, T. Hospital out-and-in-patients as functions of trace gaseous species and other meteorological parameters in Chiang-Mai, Thailand. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 15, 479–493 (2015).

Pongpiachan, S. et al. Impacts of meteorological parameters on COVID-19 transmission trends in the central part of Thailand. Aerosol Sci. Eng. 8, 370–383 (2024).

Gao, M. et al. Seasonal size distribution of airborne culturable bacteria and fungi and preliminary Estimation of their deposition in human lungs during non-haze and haze days. Atmos. Environ. 118, 203–210 (2015).

Liu, H. et al. Effect of air pollution on the total bacteria and pathogenic bacteria in different sizes of particulate matter. Environ. Pollut. 233, 483–493 (2018).

Raisi, L., Lazaridis, M. & Katsivela, E. Relationship between airborne microbial and particulate matter concentrations in the ambient air at a mediterranean site. Glob Nest J. 12, 84–91 (2010).

Yang, L. et al. Size distribution, community composition, and influencing factors of bioaerosols on haze and non-haze days in a megacity in Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 155969 (2022).

Niu, M. et al. Abundance and composition of airborne archaea during springtime mixed dust and haze periods in Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 752, 141641 (2021).

Niampradit, S. et al. The elemental characteristics and human health risk of PM(2.5) during haze episode and Non-Haze episode in Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 6127 (2022).

Ponsawansong, P. et al. Sources of PM2.5 oxidative potential during haze and Non-haze seasons in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 23, 230030 (2023).

Yan, Z. et al. The cytotoxic effects of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) from different sources at the Air–Liquid interface exposure on A549 cells. Toxics 12, 21 (2023).

Li, H. et al. Effects of heavy metals on bacterial community structures in two lead-zinc tailings situated in Northwestern China. Arch. Microbiol. 204, 78 (2021).

Sawulski, P., Clipson, N. & Doyle, E. Effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on microbial community structure and PAH ring hydroxylating dioxygenase gene abundance in soil. Biodegradation 25, 835–847 (2014).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Airborne bacterial communities in three East Asian cities of China, South Korea, and Japan. Sci. Rep. 7, 5545 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Anthropogenic impact on airborne bacteria of the Tibetan plateau. Environ. Int. 183, 108370 (2024).

Dong, S. R. et al. Distribution of microbiota in fine particulate matter particles in Guangzhou, China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 33, 306–314 (2020).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible Microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13, 581–583 (2016).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M., Usadel, B. & Trimmomatic A flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Stefan, J. et al. Phylogenetic Placement of Exact Amplicon Sequences Improves Associations with Clinical Information. mSystems 3, (2018). 10.1128/msystems.00021–18

Faith, D. P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Conserv. 61, 1–10 (1992).

Micah, A. L. C., Rob, K. & H., T., K. S. & Quantitative and qualitative Β diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1576–1585 (2007).

Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8228–8235 (2005).

Bray, J. R. & Curtis, J. T. An ordination of the upland forest communities of Southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 27, 325–349 (1957).

Bokulich, N. A. et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 6, 1–17 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the e-ASIA Joint Research Program and the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) (Grant No. 110/2021). We would like to extend our sincere acknowledgments for the partial support grant received from the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University. Additionally, we express our gratitude to the Chiang Mai Municipality for their invaluable assistance in facilitating the collection of air samples. Your support and collaboration have been instrumental in the success of our research endeavors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Initial planning of the study, supervision and guidance, data interpretation, compiling of the discussion and conclusion, and final corrections by Kraichat Tantrakarnapa (KT) , Material preparation, data collection and analysis by Wissanupong Kliengchuay(WK), Material preparation, data collection and analysis by Wantanasak Suksong(WS): Material preparation, data collection and analysis, The first draft of the manuscript by Nopadol Precha(NP), The manuscript review and editing and supervision by Kttipong Chaisri(KC), The manuscript review and editing and supervision by Suwalee Worakhunpiset(SW), Yanin Limpanont(YL) and Naomichi Yamamoto(NY).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Precha, N., Chaisiri, K., Worakhunpiset, S. et al. Comparison of airborne bacterial communities in PM2.5 between a dry-season haze period and a wet-season non-haze period in thailand. Sci Rep 15, 12918 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97966-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97966-5