Abstract

Although surgical resection combined with radiotherapy is still the preferred treatment for soft tissue sarcoma, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is becoming more popular. The goal of this research is to get a large, multicenter retrospective analysis to build a practical and validated method to predict overall survival in patients. This study was a retrospective study of 902 soft tissue sarcoma patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. We used the Cox multivariate model to build a nomogram for predicting overall survival and converted it into a web-based nomogram. To identify and calibrate the model, bootstrap resampling was used to draw receiver operating characteristic curves and calibration curves, as well as to test the clinical applicability of the model by plotting decision curves. A total of 634 patients were included in the training cohort, while the remaining 268 patients were included in the validation cohort. Overall survival was significantly influenced by disease stage, age, tumor size, grade, and radiation, and nomograms were created to predict overall survival. The area under the curve for predicting overall survival at 1, 3, and 5 years in the training cohort was 0.797, 0.751, and 0.739, respectively; the area under the curve for the validation cohort was 0.726, 0.747, and 0.698, respectively. The calibration curves showed that the model performs well in terms of calibration (prediction accuracy). In addition, the decision curve analysis demonstrates the good clinical application of the model, allowing for a greater net clinical benefit. For soft tissue sarcoma patients who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, we have developed the first novel tool to accurately predict overall survival. This tool improves clinicians’ ability to assess patient prognosis, enhances prognosis-based treatment decisions, and can be used as a guide for clinicians to consult with patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcoma is an uncommon mesenchymal cell tumor that accounts for 1% of all malignancies in the U.S., with an incidence rate of 3 per 100,000 people1. There are more than 50 subtypes of soft tissue sarcoma, most of which (about 85%) occur in the extremities2,3. For high-risk soft tissue sarcomas, surgical resection combined with preoperative radiotherapy is still the therapy of choice4. In previous studies, radiotherapy combined with surgery has been shown to have good local control rates in soft tissue sarcoma patients. However, about half of the patients with localized high-risk tumors will still develop metastases after initial treatment5.

Anthracycline-based chemotherapy is one of the treatment options available to patients with soft tissue sarcoma6. Preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy aims to reduce the size of the tumor, reduce the chance of distant metastases, and increase the number of treatment options for patients. Although preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been proven to increase disease-free survival and overall survival in individuals with high-risk soft tissue sarcoma, other experts believe treatment is only useful in patients with soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities who also have high-risk characteristics7. Chemotherapy not only provides local control of sarcomas at high risk of recurrence but also controls tumor metastasis to distant sites, hence the current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for high-risk soft tissue sarcoma at the recommended level of 2B8.

Most of the current studies on soft tissue sarcoma after neoadjuvant chemotherapy are prospective studies with relatively stringent inclusion criteria. The rarity of soft tissue sarcomas also makes it difficult to conduct large randomized clinical trials, which can be time-consuming and resource-intensive. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, on the other hand, is increasingly being employed in the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma patients. The tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage is currently the most commonly used staging for prognostic assessment of malignancies, however, the TNM stage does not take into account the underlying clinical profile of the patient. The nomogram model is a user-friendly scoring system that can be used to improve individual predictive performance by combining multiple variables9. Nomogram has higher discriminatory power in prognostic risk assessment compared to the TNM stage10. In a previous study, Robert J et al. constructed the first nomogram model for predicting the prognosis of patients with synovial sarcoma. However, unfortunately, nomograms for all types of soft tissue sarcoma patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy have not been established. We, therefore, hope to analyze patients with soft tissue sarcoma who have received pre-operative neoadjuvant to further develop a novel tool to accurately predict patient prognosis and provide clinicians with a personalized basis for the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Methods

Study participants

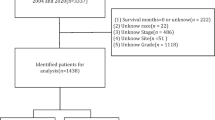

The data for this multicenter retrospective study came from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, which is the biggest publicly available database in the US, covering about 28% of the population11,12. Inclusion criteria were: soft tissue sarcoma diagnosed between 2004 and 2015; all patients received preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy; first primary malignancy; and complete clinicopathological and follow-up data. After removing patients who did not satisfy these criteria, the study ended up with 902 cases. The local ethics committee’s approval was not necessary because of the retrospective nature of the study and the fact that patient data was used anonymously and without individually identifiable information.

Study variables

In this study, the following data were extracted: sex, age, race, marital status, tumor size, tumor primary site, histological grade, histological type, laterality, T stage, N stage, disease stage, and treatment status (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy). Continuous variables including age and tumor size were used to determine the optimal cut-off values for age and tumor size based on overall survival using the X-tile procedure, which was then turned into a categorical variable. The optimal cut-off values for age were 20 and 66 years, so we divided age into 3 subgroups (< 20 years, 20–66 years, > 66 years). The best cut-off values for tumor size were 100 and 147 mm, which were also divided into three subgroups (< 100 mm, 100–147 mm, and > 147 mm). The disease stage was classified as " localized “, “regional” or “distant” according to the interpretation of the SEER database. For the site of origin of the tumor, we classify it as being located in the axial or extremity. The histological types are divided into seven groups based on the latest WHO criteria: leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, synovial sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and others.

Statistical analysis

The study used Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 25.0 to perform all statistical analyses, while R software (version 4.0.3) was used to perform the development and evaluation of the nomogram. The code for randomized grouping was entered in R software to randomly divide the included cases into training and validation groups in a ratio of 7:3. In the training cohort, univariate Cox regression was used to identify risk factors for patients with soft tissue sarcoma who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and factors that reached significant levels were included in multivariate Cox regression analyses to control for potential confounders. The Cox proportional risk hypothesis was tested using Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis. The predictive model to predict overall survival was constructed based on independent prognostic factors. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was used to analyze the nomogram’s discriminatory capacity, and the calibration curve was used to examine the nomogram’s predictive ability. The area under the curve values ranged from 0.5 (no discrimination) to 1.0 (excellent discrimination). Decision curves were also plotted for the treat-all patient scenario (representing the highest clinical cost) and the no-treatment scenario (representing no clinical benefit) as two references13. A mortality risk classification system was constructed using X-tile software to select cut-off points for mortality risk stratification, dividing patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy into three mortality risk subgroups. The nomogram-based mortality risk classification was compared using Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis and log-rank tests. Using the resulting survival probability formula, a network-based nomogram was constructed using the “DynNom” software package to accurately calculate the overall patient survival rate. All p-values were two-tailed and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

In total, 902 eligible patients with soft tissue sarcoma were identified from the SEER database. There were 634 patients in the training cohort and 268 patients in the validation cohort. The demographic and clinical features of the patients in the three cohorts are summarized in Table 1. In the total cohort, patients aged 20–66 years made up the majority (75.5%) and were overwhelmingly white (80.2%). Of these, 674 patients (74.7%) had tumors with a primary site in the extremity, 87.1% had high-grade tumors, 54.0% had limited tumors and 137 patients (15.2%) had distant metastases.

Construction and validation of a nomogram

Eight factors (histological type, disease stage, T stage, N stage, radiation status, tumor size, age, and histological grade) were substantially linked with overall survival in the univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 2). Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed the following risk factors for overall survival: disease stage (distant metastasis [HR, 3.121; 95% CI, 2.294–4.246; p < 0.01]), radiation (preoperative radiotherapy [HR, 0.651; 95% CI, 0.482–0.879; P < 0.01]), tumor size (> 147 [HR, 1.694;95% CI, 1.255–2.286; P < 0.01]), histological grade (high grade [HR,1.800; 95% CI, 1.159–2.795; P < 0.01]), age (> 66 [HR, 2.491; 95%CI, 1.486–4.175; P < 0.01]). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that clinical factors (age, disease stage, tumor size, histological grade, radiotherapy status) were significantly associated with patient prognosis, further validating the multivariate Cox regression analysis (Fig. 1).

Based on the weighting coefficients for each value obtained from Cox regression, a nomogram was developed to predict the overall survival of patients at 1, 3, and 5 years after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Fig. 2). Figure 1 displays an example of utilizing a nomogram to forecast a patient’s overall survival probability. A 40-year-old man is diagnosed with soft tissue sarcoma (histological grade is high grade, tumor size is 60 mm and the tumor is localized); he receives neoadjuvant chemotherapy and postoperative radiotherapy. By adding up the scores, he would have scored 274 points, which suggests an overall survival rate of 94.55%, 79.3%, and 74.4% at 1, 3, and 5 years respectively. The area under the curve values predicted in the training cohort was 0.797, 0.751, and 0.739 for 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively, and the area under the curve values in the validation cohort were 0.726, 0.747, and 0.698, respectively (Fig. 3). The internal and external calibration curves are shown in Fig. 4, indicating a high level of agreement between the observed survival probabilities and the survival probabilities predicted using the nomogram. The nomogram’s clinical usefulness was assessed using decision curve analysis. As shown in Fig. 5, a net benefit was obtained when the threshold probability was approximately 0.1 to 0.9 in the training cohort and 0.1 to 0.8 in the validation cohort, indicating the good potential clinical validity of the nomogram.

Risk stratification system and web-based nomogram

Risk stratification was performed using X-tile software, and patients from both cohorts were divided into a high-risk group (total score > 325), a middle-risk group (295 ≤ total score ≤ 325), and a low-risk group (total score < 295). Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests were used to validate the stratification of mortality risk, and the results showed significant differences in the probability of survival between the different risk subgroups (Fig. 6, p < 0.05). A web-based nomogram was built to predict the overall survival of patients with soft tissue sarcoma a, as illustrated in Fig. 7 (https://hzhspine.shinyapps.io/pstsncps/). Using the web-based nomogram, we can easily and quickly assess patient prognosis based on the input clinical factors in our clinical work.

Discussion

Soft tissue sarcomas are a group of malignant tumors of different natures, with a wide range of pathological histological subtypes, mainly typed according to their histological appearance, supplemented by immunohistochemistry and molecular14. The clinical features and prognosis vary depending on the histological subtype of the pathology. Most of these rare tumors originate in skeletal and extra-skeletal connective tissue, including the peripheral nervous system. However, they can originate anywhere in the body, mainly in the extremities, pelvis, and retroperitoneum15,16. The pathological histological subtypes of soft tissue sarcomas are classified in several ways, the most common being malignant fibrous histiocytoma (28%), followed by smooth muscle sarcoma (12%), liposarcoma (15%), synovial sarcoma (10%), and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (6%)17. In our study, the tissue types that accounted for a relatively high proportion were synovial sarcoma, liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be beneficial for patients with soft tissue sarcoma. Firstly, preoperative induction chemotherapy can shrink the tumor, allowing for a reduction in the extent of surgery, ensuring negative margins as far as possible as well as reducing the incidence of amputation. Secondly, preoperative chemotherapy can reduce the risk of distant tumor metastases. Thirdly, surgery and radiotherapy have the potential to reduce tolerance to chemotherapy and therefore neoadjuvant chemotherapy is chosen over adjuvant chemotherapy. Finally, patients treated with preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be better screened for sensitive chemotherapeutic agents18. Previous studies have shown a relatively poor prognosis for patients with soft tissue sarcomas of advanced age, larger tumors, and deeper locations2. Age, disease stage, tumor size, grade, and radiation were all risk variables for soft tissue sarcoma patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, according to our findings.

In various studies, age has been proven to be a prognostic variable for a poor prognosis in soft tissue sarcoma. Our research also found that after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, age was a risk variable for soft tissue sarcoma, with older age being related to a worse prognosis. The reason for this may be due to the lower use of multidrug combination chemotherapy in patients with advanced age-associated19. The older the patient, the higher their Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score and the less tolerable the application of chemotherapy while the side effects of chemotherapy increase. Previous studies have shown a significant reduction in 5-year survival for soft tissue sarcoma patients with tumors > 15 cm20. In our data, we have observed that patients with relatively large tumors are treated more frequently with neoadjuvant chemotherapy because of its ability to achieve a reduced stage. However, it is known that the larger the diameter of the tumors, the more unevenly distributed the blood vessels are, and the more likely it is that the center of the tumor will become hypoxic and form foci of necrosis, and therefore the larger the tumor diameter, the worse the prognosis21. This is consistent with our findings that tumor diameter is an independent prognostic factor for soft tissue sarcoma after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The larger the tumor diameter, the worse the prognosis, both due to the tumor itself and possibly due to the residual dead space created after removal of the larger tumor, which can easily develop into plasmacytomas and hematomas, and subsequent infection, leading to a poorer prognosis22.

Based on the grade’s survival curves, we can see that high histological grade patients have a worse overall survival rate than low histological grade patients and that the higher the histological grade, the greater the risk of local recurrence and metastasis23. Patients with a high histological grade are more likely to die of systemic disease in other organs before local recurrence because of the higher risk of distant metastases24. The prognosis of localized soft tissue sarcoma, one of the independent factors of prognosis, is much better than that of patients with distant metastases. A 5-year overall survival rate of approximately 80% has been reported for patients with localized soft tissue sarcoma. In contrast, the prognosis for patients with primary metastatic soft tissue sarcoma is much worse, with the 5-year overall survival of approximately 16%25. Distant metastases mean that the overall aggressiveness of the tumor is higher and the likelihood of distant metastases from other sites increases26.

The primary goal of surgical treatment for soft tissue sarcomas is to remove the tumor completely. In some patients, however, the surgeon sometimes has to choose between sacrificing the neurovascular bundle and/or amputation and preserving function, especially in tumors located near functional or circulatory critical areas3. Therefore, radiotherapy is often chosen by doctors as a means of local control of the tumor. However, the timing of radiotherapy is still debatable. Postoperative radiotherapy aims to destroy residual tumor cells after surgery, whereas the theory behind preoperative radiotherapy is to shrink the tumor27. Radiotherapy combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy significantly improves local control rates, but the impact on overall survival is limited and requires individualized trade-offs28. However, since the SEER database does not provide clear indications for radiotherapy, this may have led to selection bias, thus affecting the accuracy of the prognostic impact of radiotherapy in the current study.

Although some nomograms associated with soft tissue sarcoma have been reported in some previous studies. However, it has to be mentioned that most of them were developed for soft tissue sarcomas at a specific primary site or a specific histological subtype of soft tissue sarcoma29,30. Our development of nomograms for soft tissue sarcoma patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy has not been reported before. Compared to previously developed nomograms, our model showed better predictive accuracy in predicting the overall survival of soft tissue sarcoma patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. However, there are still some shortcomings in our study: firstly, our study is retrospective and there is inevitable selection bias. Secondly, the SEER database does not contain details of the drugs, doses, and cycles used to improve the chemotherapy regimen, and the impact of its chemotherapy regimen on patients with different subtypes of soft tissue sarcoma still needs further discussion. Thirdly, we have no way of knowing the postoperative patient’s cut margins, and whether they are negative or not will inevitably have an impact on the results.

Conclusions

The nomogram and risk classification system we constructed accurately predicted the overall survival of patients with soft tissue sarcoma after receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The constructed nomogram has high accuracy and validity for individualized prognostic assessment. This study will provide a relatively reliable prognostic judgment for identifying high-risk patient groups. In addition, further developed web-based models are more conducive to wider use in clinical work.

Data availability

The dataset from the SEER database that was generated and/or analyzed during the current study is available in the SEER dataset repository (https://seer.cancer.gov/). The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TNM:

-

Tumor node metastasis

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for the social sciences

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results

References

Siegel, R., Miller, K., Fuchs, H. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2021. Cancer J. Clin. 71 (1), 7–33 (2021).

Kungwengwe, G. et al. Preoperative Versus Post-operative Radiotherapy for Extremity Soft Tissue Sarcoma: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Long-term Survival (JPRAS, 2021).

Aiba, H. et al. Clinical outcomes of radio-hyperthermo-chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma compared to a soft tissue sarcoma registry in Japan: a retrospective matched-pair cohort study. Cancer Med. 7 (4), 1560–1571 (2018).

Moon, T. et al. PROMIS scores of patients undergoing neoadjuvant and adjuvant radiation therapy for surgically excised soft tissue sarcoma. Clin. Translational Radiation Oncol. 31, 42–49 (2021).

Neuberg, M. et al. Surgical management of soft tissue tumors of the abdominal wall: A retrospective study in a high-volume sarcoma center. Journal of surgical oncology 2021.

Younger, E. et al. Priorities and preferences of advanced soft tissue sarcoma patients starting palliative chemotherapy: baseline results from the HOLISTIC study. ESMO Open. 6 (5), 100258 (2021).

Issels, R. D., Lindner, L. H., Verweij, J., Wust, P. P. & Hohenberger, P. P. Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy alone or with regional hyperthermia for localised high-risk soft-tissue sarcoma: a randomised phase 3 multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 11 (6), 561–570 (2010).

Alessandro, G. & Jones, R. L. The value of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in localized High-Risk Soft-Tissue sarcoma of the extremities and trunk. JAMA Oncol. 4. (2018).

Deep learning radiomic. Nomogram to predict recurrence in soft tissue sarcoma: a multi-institutional study. Eur. Radiol. :1–13. (2021).

Pasquali, S. et al. The Impact of Chemotherapy on Survival of Patients with Extremity and Trunk Wall Soft Tissue Sarcoma: Revisiting the Results of the EORTC-STBSG 62931 Randomised Trial Using Sarculator, a Validated Nomogram-Based Risk Assessment Tool. Social Science Electronic Publishing.

Lin, Z., Yan, S., Zhang, J. & Pan, Q. A nomogram for distinction and potential prediction of liver metastasis in breast Cancer patients. J. Cancer. 9 (12), 2098–2106 (2018).

Siegel, R., Miller, K. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. Cancer J. Clin. 69 (1), 7–34 (2019).

Kerr, K., Brown, M., Zhu, K. & Janes, H. Assessing the clinical impact of risk prediction models with decision curves: guidance for correct interpretation and appropriate use. J. Clin. Oncology: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 34 (21), 2534–2540 (2016).

Rick, L. M., Haas, Hans, Gelderblom, Stefan, S., Hester, H., Boven, V. & Astrid Scholten: A phase I study on the combination of neoadjuvant radiotherapy plus pazopanib in patients with locally advanced soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities. (2015). Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden).

Group, T. E. E. S. N. W. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 23. (2012).

Stiller, C. A., Trama, A., Serraino, D. & Rossi, S. Etc: descriptive epidemiology of sarcomas in Europe: report from the RARECARE project. Eur. J. Cancer. 49 (49), 684–695 (2013).

Mehren, M. V. et al. Soft tissue sarcoma, version 2.2014. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. Jnccn. 12 (4), 473 (2014).

Baldini, E. H., Le Cesne, A. & Trent, J. C. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, concurrent chemoradiation, and adjuvant chemotherapy for High-Risk extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educational Book. 2018(38):910–915 .

Graham, D. S., Onyshchenko, M., Eckardt, M. A., Dipardo, B. J. & Kalbasi, A. Low rates of chemotherapy use for primary, High-Grade soft tissue sarcoma: A National Cancer database analysis. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Network: JNCCN. 18 (8), 1055–1065 (2020).

Pollock, R. E. et al. New perspectives for staging and prognosis in soft tissue sarcoma.

Hanahan, D. & Folkman, J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 86 (3), 353–364 (1996).

Farhan-Alanie, O., Ha, T., Doonan, J., Mahendra, A. & Gupta, S. Inflammatory Prognostic Scoring Systems Are Risk Factors for Surgical Site Infection Following Wide Local Excision of Soft Tissue Sarcoma (orthopedie traumatologie, 2021).

Biau, D. J. et al. Local recurrence of localized soft tissue sarcoma: a new look at old predictors. Cancer 118(aop). (2012).

Muehlhofer, H. et al. Oncological outcome and prognostic factors of surgery for soft tissue sarcoma after neoadjuvant or adjuvant radiation therapy: A retrospective analysis over 15 years. Anticancer Res. 41 (1), 359–368 (2021).

Matsuoka, M. et al. Surgical Resection of Primary Tumor in the Extremities Improves Survival for Metastatic soft-tissue Sarcoma Patients: a population-based Study of the SEER Database. Clinical & Translational Oncology (official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico, 2021).

Gronchi, A., Vullo, S. L., Colombo, C., Collini, P. & Casali, P. G. Extremity soft tissue sarcoma in a series of patients treated at a single institution: local control directly impacts survival. Ann. Surg. 251 (3), 506–511 (2010).

Haas, R. et al. Cellular radiosensitivity of soft tissue sarcoma. Radiat. Res. 196 (1), 23–30 (2021).

Byun, D. et al. Modern management of High-risk soft tissue sarcoma with neoadjuvant chemoradiation: A Single-center experience. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 44 (1), 24–31 (2021).

Squires, M. et al. Extremity soft tissue sarcoma: A Multi-Institutional validation of prognostic nomograms. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 29 (5), 3291–3301 (2022).

Callegaro, D., Miceli, R., Mariani, L., Raut, C. & Gronchi, A. Soft tissue sarcoma nomograms and their incorporation into practice. Cancer 123 (15), 2802–2820 (2017).

Funding

This study was funded by the Clinical Medical College of North Sichuan Medical College - Affiliated Hospital Research and Development Plan Project (2023-2GC003), Chongqing Graduate Research Innovation Project (Q.F., Grant No. CYB23197), and The First-class Discipline Construction Project of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (Q.F., Grant No. CYYY-BSYJSCXXM-202304).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC J and ZP Z conceived and designed the study. CC J and DX H performed the literature search. CC J and YL H generated the figures and tables. CC J and X C analyzed the data. CC J wrote the manuscript and ZP Z critically reviewed the manuscript. CC J and ZP Z supervised the research. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study is based on data from public databases and therefore does not require informed consent from patients. The local ethics committee’s approval was not necessary because of the retrospective nature of the study and the fact that patient data was used anonymously and without individually identifiable information.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jian, C., Huang, D., Huang, Y. et al. Development and validation of a novel model for patients with soft tissue sarcoma who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Sci Rep 15, 14211 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98117-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98117-6