Abstract

The study was conducted prospectively on 107 children (74 boys). Eighty-three children were born at term (39 ± 1), 24 were born prematurely (33 ± 4). The study included the qualitative assessment at three months of age, eye contact and traction response assessment, and the quantitative assessment at 3, 9, and 16 months of age. The timely achievement of crawling and sitting down depended on the same qualitative characteristics at three months of age: hands and lower limbs and on the segmentally extended spine and shoulder blades. Social walking was influenced by the qualitative assessment of the position of the lower limbs at three months of age. The eye contact substantially impacted walking; the correct traction test moderately impacted crawling and sitting down. The qualitative assessment at three months is highly predictive for crawling and sitting down at nine months and social walking at 16 months. The correct traction test appears to predict crawling and sitting down, while eye contact is essential for social walking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A set of diagnostic tools assessing motor development should identify children at risk of psychomotor disorders, such as cerebral palsy or delayed or impaired motor development. Such a set should include the observation of milestones and the quality of performance of given motor functions. Age norms for basic motor skills provide valuable diagnostics for “typical” development, but cultural differences in child-rearing practices may influence the age of skill onset1,2,3,4. Therefore, the proper achievement of the milestones seems to predict the correct development of motor functions and optimal development by a child in the future, as well as in the intellectual sphere5,6,7,8,9.

Many authors believe that the assessment of spontaneous motor skills at three months has strong predictive overtones and, at the same time, allows for catching abnormalities early enough to start therapy; it is also believed that this is a crucial moment for the initiation of purposeful movements. Three months after birth - or from 2 to 4 months - is also the age of significant changes in motor development10. These consist of a transition from endogenously generated diverse movements that primarily explore and sculpt the nervous system to movements that can be increasingly modified and adapted to the constraints of the environment. Analysis of motor development at the third month of an infant’s life has also become essential for other reasons. So far, the early initial diagnosis of cerebral palsy (CP) has been made before five months of age corrected age. Before five months of age, this was done based on the Prechtl Quality Assessment of General Movements (GMA), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), or Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination (HINE) assessment11,12. Using all three diagnostic capabilities: GMA, HINE, and MRI evaluation, infants with detectable neonatal CP risk factors can be diagnosed as early as three months of age (corrected for prematurity) with a sensitivity as high as 97%13,14. Vojta, the author of the diagnostic system and the creator of neurodevelopmental therapy widely used in many countries around the world, believed that correct motor development at three months is summarized in correct quadriceps support in the supine position (support occurs at the head, shoulder blades, and pelvis) and performing symmetrical elbow support in the prone position (triangle of support - elbows and pubic symphysis). A stable symmetrical position with spinal uprightness and correct head control is associated with accomplished craniocaudal development at three months of age13,14.

The article’s authors have already raised this issue in previous publications, specifying in detail what quantitative and qualitative patterns should be analyzed at this age15,16. Quantitative assessment (global assessment) indicates the age of the occurrence of a most advanced motor function, i.e., the performance of individual milestones. The milestone does not need to be performed flawlessly, and it is sufficient for the child to manifest it in any way or at least strive to achieve it13. Such an example is the achievement of sitting down or crawling, which occurs, for example, after rolling from a supine to a prone or a crawl position.

The qualitative assessment (the analysis of partial patterns) describes how movement is performed (the correctness of the milestone). A partial pattern is always a component of a motor function, i.e., each global (quantitative) pattern consists of a dozen or so smaller partial (qualitative) patterns13.

The assessment of the quality of mobility, describing the way of performing movements, may help in the early detection of children with motor disorders and early therapy planning. This type of assessment has the predictive value for significant motor disturbances like cerebral palsy (CP) and minor problems and motor delay4,16,17,18,19,20. This system of analysis of motor development is widely used by physiotherapists in many countries in Europe and around the world, and that is why we created and validated, based on this system of assessment, The Quantitative and Qualitative Developmental Assessment Worksheet20. Previously, it was used and described in several publications evaluating the impact of motor development assessed at three months of age on turning to the side and asymmetrical support on an elbow (at 4.5 months); support on the extended upper limbs and turn from back to the stomach (we examined it at six months of life); creeping (at 7–8 month); crawl position (at seven months); independent reaching of the sitting position (at eight months) and reaching of the erect posture (at nine months)4,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Several assessment methods are used because no golden standard for examining motor performance is widely recognized in the first months of life. There is no worldwide consent on which system is the most reliable, nor is any of them recommended in Poland4,16,17,18,19,20. The above approach to assessing motor development is crucial for a therapeutic program, identifying which child needs therapy based on the results of a functional diagnosis and which child is at risk of developing neurodevelopmental disorders22.

Our research also checked the traction test and eye contact at 3 months of age. The traction test is widely used as a screening test during the exam of motor development in the first months of life. Vojta thoroughly described and demonstrated that this test is easy and quick to perform13,23. The traction test shows the complex mechanism of interaction of the motor component with the maturity of both the central adjustment of movement (head control) and the appropriate muscle strength necessary for its performance (especially the efficiency of the shoulder girdle, but also the paraspinal muscles). Therefore, it is a good summary of the maturity of the motor system at this stage of development and, at the same time, a guarantee of further correct motor development. Unfortunately, in the literature, the analysis of the traction test is often understood as observing the position of the head only24,25. Kaler et al. believe that the symptoms are the same regardless of whether hypotonia is of central or peripheral origin. The most important feature of the “flaccid child syndrome” is an apparent delay in raising the head when the infant is pulled to sit26. Like other researchers, Kaler focused mainly on observing the head, which does not agree with the Vojta traction test standard13,23,24,26.

Test pull to sit has been used in diagnostics for decades to assess the head’s posture in a child raised from a supine lying position to a vertical sitting position. However, when the child is pulled up to a sloping position (approximately 45 degrees from the horizontal), the proper traction test allows us to observe the whole body’s reaction and the extremities in this unstable position13,23. Care must be taken to bypass the grasp reflex of the hands. The examiner places his or her finger from the direction of the ulnar side in the child’s hand. With the other fingers, the examiner grasps the child’s distal forearm without touching the back of the hand. This exteroceptive stimulus should circumvent the grasp reflex.

The traction test shows postural control development, especially in looking for the relationship between the position of the head and the torso23,27. This test belongs to the seven postural responses in the Vojta concept, though it is used as a single by many13. It is performed in a strictly defined manner, and the correct result is clearly defined28. During the starting position, the examined child was placed on its back with its head positioned in the center line. The investigator pulled the child up by the hands to an angle (between the torso and the ground) of 45 degrees. If possible, eye contact with the baby should be made at the very beginning of the examination.

Poor eye contact in infants may indicate a severe underlying disease, such as neurological or ocular disease29. Infants develop gaze-following abilities between 2 and 4 months, which become relatively stable by 6–8 months. Orienting to gaze cues becomes almost automatic, with an adult’s gaze direction causing fast visual attention shifts even in infants as young as three months of age30.

Examining eye contact and using optical orientation by the child is an element of motivation to achieve a specific function in the first year. This examination should be performed very early. The age of three months (after the second and before four months) is an excellent time to check a child’s eye contact; additionally, infants visually discriminate between happy and angry facial expressions at this age31. We analyze it by evoking, e.g., a social smile while maintaining eye contact or by actively focusing the eyes on the face of the investigator or a toy9,32.

Vojta described the importance of eye contact in the emergence of new motor functions and milestones, referring to it as visual orientation, which is a factor that motivates development in the first year. Correct eye contact is linked through optical orientation to motor patterns. It has a motivational effect on lifting the head, achieving upper limb support, and determining interest in the environment28,33.

In the literature, different research methods analyze early motor development and achieving later milestones. Analysis of early motor development and its impact on further development was performed by Bradshaw et al. They evaluated postural and head control monthly from age 1 month to 6 months during a pull-to-sit task. They showed that atypical postural development and persistent presence of head lag at 4 months may be important early indicators of social and language vulnerabilities, including autism spectrum disorder34. Another researcher used inertial movement sensors to record full-day leg movement activity in children between 1 and 12 months of age and its influence on the speed of starting walking35.

Our research analyses which development elements in the third month of life may be related to delays or lack of milestones such as crawling, sitting, or walking22.

Unsupported sitting is described in many scales and motor development assessment sheets. According to WHO studies, it occurs around 5.4 months36; regrettably, WHO does not describe the function of independent sitting down. On the other hand, the authors of the Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS) provide the time range for independent sitting down (distinguishing between sitting with support, without it, or with rotation) and the time frame for assuming a sitting position, describing its occurrence between 7.5 and 10 months of age37. Independent sitting down is a motor skill a child achieves by lying on the stomach or the back. When analyzing the literature on the subject, we assumed that every child should show this ability at 9 months (finished nine months, i.e., 36 weeks, but before 10 months, i.e.,40 weeks)7,32,38,39,40.

Around the same time as independent sitting, children assume crawling. In our research, we analyzed the crawling pattern as a quantitative feature, did not assess whether the spine is flat, and did not look carefully at whether elbows and knees are aligned under shoulders and hips (without analyzing qualitative patterns). Various authors identify crawling with belly crawling or bear crawling, while in our research, it means moving around on open palms and knees10,41,42,43. The torso is then raised above the ground owing to the straightened upper limbs, while the lower limbs are bent at the hip and knee joint; we observe reciprocal arm and leg movement with trunk rotation. Crawling is not only one of the motor milestones but is also known to positively affect an infant’s development in terms of various functions. Crawling facilitates the development of sensory and motor systems of the body44. It has also been shown that the longer an infant crawls, the greater the ability to perceive space and search for objects45. The Campos et al. paper shows that infants’ hands and knees crawling experience relates to a wide range of changes in psychological functioning in the second half of the first year of life44. According to the authors of AIMS, crawling occurs between 8.5 and 13 months37, while according to WHO, it occurs around 8.3 months on average36. Following Vojta, we have identified nine months as the cut-off age for crawling13.

The term “walking pattern” means achieving bipedal locomotion on two lower limbs independently and freely. In “social walking,” the child can move from standing to squatting and back to standing with controlled flexion and extension of hips and knees and go, for example, to pick up a toy that is a short distance away, turn around, and come back13,37. The child can move independently of other people to develop their social skills such as exploring the surrounding world, e.g., by touching various objects; the child plans their actions better and better, cooperating with others, e.g., by playing with other children, solving more and more complex problems13. The social walking is considered the most mature type of walking in children. In the presented work, after analyzing the literature, the 16th month of age was considered the walking standard, i.e., the ability to move from one room to another, not the ability to take the first steps10,32,46.

Considering all the methods of assessment mentioned above, we decided to investigate all children in parallel with the previously described “Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment Sheet” and the traction test and to check if they showed eye contact as expected for the age of three months. We aimed to investigate which partial movement patterns in the third month of life predict the timely achievement of crawling, sitting down, and walking and whether traction test or eye contact may predict these milestones.

Method

Participants

Inclusion criteria: The study included children under the care of a rehabilitation clinic between 2018 and 2022, recruited in the West and East regions of Poland, whose parents or guardians asked for a screening test to exclude or confirm developmental abnormalities (for example, asymmetry of movement, low muscle strength, poor head control). Children referred for functional assessment by pediatricians or neurologists were also included. Exclusion criteria were genetic or metabolic disorders, severe congenital disabilities, microcephaly, macrocephaly, or extreme preterm birth (below 28 gestation weeks). Demographics on a child’s health were taken from a medical record book or discharge summaries. The study was conducted prospectively on 107 children (74 boys and 33 girls). Eighty-three children were born at term (gestation week 39 ± 1, body weight 3465 ± 395 g), and 24 were born prematurely (gestation week 33 ± 4, body weight 2225 ± 794). Children born prematurely were screened at the corrected age47. Children born preterm, before 37 weeks of completed gestation, are at higher risk of motor, cognitive, and behavioral problems compared to children who are born at term48. When analyzing the type of delivery, 56 children were born by vaginal delivery; 98 of the subjects were born in good condition according to the Apgar score (8–10), 7 in a semi-severe condition (4–7), and two in a severe condition (0–3). Respiratory distress syndrome occurred in nine children, while hypotrophy was found in 23 subjects; and 23 children had hyperbilirubinemia, six children had intraventricular hemorrhages (IVH), four were affected by grade I IVH, two with grade II. All parents and guardians consented to their child’s examination.

Assessment

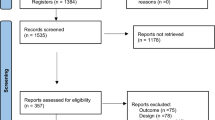

Children under study were assessed by the two experienced physiotherapists at the age of 3 months (after 12 weeks, before 16 weeks of life), nine months (after 36 weeks, before 40 weeks of life), and 16 months (after 64 weeks, before 68 weeks of life). If a child did not reach the expected milestone on time (sitting down and crawling at the latest at nine months, walking at the latest at 16 months), the therapist asked the parents/caregivers to show up once a month until the child achieved the given milestone, and this age was then noted. At the age of 3 months, each child was observed by the therapist in the following conditions: the calm, the fed child was placed on the table, in a warm ambiance, in the supine and then prone position. Similarly, children aged 9 and 16 months were placed on a theraband exercise mat and observed for spontaneous ability to sit down, crawl, or walk. The time needed for observation is determined by the correctness (performed the item according to the criteria specified for mastery ) of the motor performance: if the child performed all expected partial motor elements repeatedly (3–4 times to exclude incidental performance), the examination was over. If any problems were noticed, the observation lasted longer. The study is a part of a more extensive analysis based on the novel idea of quantitative and qualitative assessment of motor development at three months of age (based on a validated Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment Sheet)20. Inter and intra-observer reliability was established to be very high17,19. Figure 1 presents the time flow of the study.

Quantitative assessment at the age of 3 months

This assessment consisted of the fulcrum quadrilateral in the supine position (head in the body axis, upper limbs aiming at the midline, lower limbs flexed up to 90 degrees in the hip and knee joints, foot in an intermediate position), and symmetrical support on the elbows in the prone position (elbows above the shoulder line). Whether a child achieved a given milestone (YES/NO) was recorded.

Qualitative assessment in the third month

At three months, a qualitative assessment was also performed, which included 15 elements in the supine and 15 in the prone position. In the supine position, the assessment involved head symmetry; shoulder in a balance between external and internal rotation; wrist in an intermediate position; palm in an intermediate position; thumb outside; spine in segmental extension; pelvis extended; lower limb situated in moderate external rotation and bent at the right angle at hip and knee joints (lower limb lifting above the substrate); foot in the intermediate position. In the prone position, the assessment involved isolated head rotation; arm in front: forearm in an intermediate position, elbow outside of the line of the shoulder; palm loosely open; thumb outside; spine in segmental extension; scapula situated in medial position; pelvis in an intermediate position; lower limbs situated loosely on the substrate; foot in an intermediate position4,16,17,18,19,20. Both sides were assessed for symmetrical parts of the body to exclude asymmetry. Each element was assessed as 0 – element performed only partially or entirely incorrectly, 1 - element performed entirely correctly. The duration of the examination performed by the physiotherapist was between 10 and 15 min. Each assessed element had to be observed at least at least three times during the test (repetition of a given activity). A maximum of 15 points could be given for the supine position (supine total) and a maximum of 15 points for the prone position (prone total). Interobserver reliability ranged from 0.870 to 1.000, while intraobserver reliability was equal to 1. Previously, this type of examination was used in assessing children aged three months, and the comparison between physiotherapeutic and neurological assessment showed high agreement, with high conformity coefficients (z=− 5.72483, p < 0.001)17,19.

Traction test

In the starting position, the examined child was placed on its back with its head in the center line. The investigator pulled the child up by the hands to an angle of 45 degrees. The child’s hands should be grasped simultaneously at the elbow and by the distal part of the forearm to use the grasping reflex of the hand. If possible, eye contact with the baby should be made at the very beginning of the examination. The child should be calm and fed for the examination. The traction test of a hungry or upset child may not be reliable13. At three months, during the traction test, the head should rise above the ground in line with the spine and remain in the plane of the torso, and the child’s lower limbs should bend towards the abdomen. The head is symmetrical without the lateral bend. Abnormal results of the traction test in the third month of life are the following: the head does not follow the trunk line, the lower limbs are not actively bent to the abdomen, the lower limbs are straightened or stay on the ground, the torso remains flaccid, and asymmetry of the head or torso position is visible25,49,50. As part of the overall assessment, a traction test was performed for each child at the age of 3 months. If the traction test at 3 months was incorrect, the investigation was repeated until the child performed it correctly for the current or actual age; this age was then noted and shown as a result.

Eye contact was assessed by observing if a child lying on the back actively focused the eyes on the investigator’s face three times within 2 min. It was noted whether the child achieved eye contact (YES/NO).

Quantitative assessment at the age of 9 months

All children were examined in terms of the achievement of independent crawling and sitting down at the age of 9 months. It was recorded whether a child achieved a given milestone (YES/NO); if not, it was still observed, and the month when this skill was achieved was recorded, to assess the severity of motor delay. The child had to independently demonstrate the crawling function by covering a distance of at least 1 m, sitting down independently, and maintaining this position for at least 5 s.

Quantitative assessment at the age of 16 months

The so-called social walking was considered during the assessment at 16 months of age. Whether a child achieved a given milestone (YES/NO) was recorded. Walking was assessed by achieving an upright position (at the ladders/chair or independently), and then the child had to walk from one room to the next. The observation period for children who did not begin to walk at 16 months of age was extended to 26 months, and the month when they achieved this ability was recorded to assess the severity of the delay in motor development. A physiotherapist performed the tests with many years of experience in functional diagnostics of children and a certified teacher of the Vojta method.

All parents or caregivers expressed their written informed consent to their children’s participation in the study. All experimental protocols were approved by the Bioethics Committee of Poznan University of Medical Sciences University (approval no.1105/18). All methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations.

Statistics analyses

The mean with standard deviation was used to describe interval variables after a preliminary assessment of the normality of the distribution with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Numbers and relatives described dichotomous variables (0–1), and the chi2 test of independence was used to test for intergroup differences (if Cochrane conditions were met; if not, the exact Fisher test was used). Medians and interquartile range [Q1–Q3] were used to describe ordinal variables, and a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with Dunn’s post hoc tests was used to test intergroup differences when significant differences were shown. A logistic regression model was used to assess the relationship between third-month assessment items and milestone achievement (crawling, sitting down and walking). Model results were presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). ROC curves were used to check if qualitative assessments at the third month of life had prognostic properties for milestone attainment. AUC, sensitivity and specificity, and cut-off point were given as results. All tests were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

First, it was checked whether the study group should be analyzed regarding the occurrence or absence of prematurity. When children born at term were compared to those born prematurely (using a corrected age), it was found that only in the supine position did they differ from each other (p = 0.02); therefore, it was decided later in the study not to analyze the group due to the presence or absence of prematurity. The analysis also did not consider the impact of risk factors. Then, the relationship between the quantitative and qualitative motor assessment results, traction test, eye contact, and the achievement of subsequent milestones was checked: crawling, sitting down, and walking (Table 1). The correct traction test usually coexisted with the correct eye contact (27/28 children). These children developed completely correctly and achieved all their milestones on time (see Table 1, group YES–YES).

The study group was divided based on whether the child demonstrated a correct traction test and made eye contact in the third month. The number of children in the subgroups and the significance of the difference using the chi2 test (the p-test value is given), or the median and quartiles, as well as the min-max range, and the significance of the difference using the Kruskal Wallis ANOVA test are given (the value of the H and p test is given). Not all children achieved the studied milestones, hence the different numbers in the lines. The results are presented in Table 1.

Only one child showed the correct traction test in the third month of life but did not make eye contact, and because it was a single case, the child was not included in the analysis. This child scored 9 points in the qualitative assessment in the supine position and only 3 in the prone position, although born at term and scored the maximum points according to the Apgar scale. The child crawled and sat down and achieved walking at 14 months of age.

The differences between the first group, which showed the correct traction (as defined by Vojta) and correct (as described in the literature) eye contact (YES–YES), and the two other groups were always significant, and there was no difference between the group that did not show correct traction but correct eye contact group (NO–YES) and the group that showed correct traction and no correct eye contact (NO–NO). Children who did not show correct traction nor eye contact (n = 33) scored low in assessing qualitative elements in the prone and supine position and achieved the milestones later (2–3 months of delay).

Analyzing the relationship between the elements of qualitative assessment in the supine position and milestones such as crawling, sitting down, and walking, we observed that crawling and sitting down are built around the same core; achieving them depends on the correct positioning of the hands and lower limbs. Whether the child would walk was influenced by the qualitative assessment of the position of the lower limbs at three months of age (Table 2).

As in the supine and prone positions, the timely achievement of crawling and sitting down depended on the same qualitative characteristics: hands (palm and thumb) and lower limbs and additionally on the segmentally extended spine and scapulae positioned medially. Both milestones occur (are assessed) in the child’s development simultaneously, i.e., in the ninth month of life. However, achieving walking depends on the correct positioning of the lower limbs (Table 3).

The influence of eye contact and the correct traction test in the third month of life on the timely achievement of crawling, sitting down, and walking is presented in Table 4. Eye contact strongly impacted walking, whereas the correct traction test showed a moderate impact on crawling and sitting down (Table 4).

Finally, the ROC curves were used to assess the impact of summarized qualitative assessment (represented by the sum in the prone and supine positions, respectively) on the achievement of the selected milestones. All three milestones were predicted with very high sensitivity and specificity, and slightly higher values were shown for the assessment in the supine position. All models were highly significant. The qualitative assessment at the age of three months is highly predictive for the attainment of crawling and sitting down at the latest at the age of 9 months and social walking at the latest at 16 months (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The study aimed to show which partial movement patterns in the third month of life may predict the timely achievement of crawling, sitting down, and walking and whether traction test or eye contact may predict these milestones.

We have shown that the absence of eye contact assessed in the third month of life may indicate deeper problems. Its absence was observed mainly in children with low qualitative assessment in the third month of life, and the time of achieving crawling, sitting down, or walking was mostly delayed. It should also be noted that eye contact is essential for so-called social walking.

Barbosa et al. described the relationship between delayed head control on the traction test and a future diagnosis of cerebral palsy51. At the same time, Flanagan et al. found that delayed traction test at six months of age is associated with an increased risk of autism49. Children with an abnormal result on the traction test as the only test component should continue to be observed for both motor development and mental, social, and cognitive development as long as the delay in head control on this test continues in the following months.

The traction test assesses the child’s motor maturity and indicates correct development in the third month of life. In our study, the pattern of differences, always significant between the correct group and two others, and no difference dependent on eye contact if the traction test was not correct, indicates that the traction test differentiates the examined children better in terms of their motor development than the assessment of eye contact. Our research showed the importance of a holistic view of an infant, considering the position of the head, torso, and lower limbs to the same extent. Regarding the relationship between the elements of qualitative assessment in the supine position and the achievement of the traction test and milestones such as crawling, sitting down, and walking on time, it was found that the traction test strongly depends on the correct operation of the upper body, i.e., the shoulder girdle (shoulder in balance) and spine and isolated head rotation, which is consistent with the diagnostic tests of a flaccid child. Also, the ROC curves analysis showed that the summarized qualitative assessment is highly predictive for attaining the selected milestones, with a cut-off point above 6 out of 15 in the supine position and above 5 out of 15 in the prone position. The data in Tables 2 and 3 indicate which elements are the most important and should be carefully followed when a child is under observation.

No studies were found that would analyze the influence of individual elements of the traction test on the achievement of milestones. When describing the diagnosis of a hypotonic child, Igarashi et al. showed that an incorrect result in the maneuver of pulling an infant to sit is much more common in disorders of the central nervous system than in neuromuscular diseases52. The postural control checked by the traction test may be abnormal in infants with low birth weight, low gestational age, brain injury, and mechanical ventilation. However, assessed in isolation from other studies was not related to a neurological examination at two years of age, as stated by Pineda50. Infants maintaining a delay in the traction test should be indicated for an urgent extension of the diagnosis, as confirmed by Bentzley25. Vojta’s and our research also confirm this fact13. Children assessed with traction test used as single and showing abnormal results should be analyzed qualitatively, indicating children at risk of abnormal development.

In previous studies, using the validated “Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment Sheet,” we have shown that correct qualitative development at three months is a good predictor of independent reaching of the sitting position16. We observed that the achievement of crawling and sitting down depends on correctly positioning the hands and lower limbs. On the other hand, whether a child would walk depends on the qualitative assessment of the position of the lower limbs at three months. Using a similar approach, describing abnormal quantitative and qualitative patterns concerning normal motor ontogenesis in the prone and supine position at three months, stated that this is an absolute indication for therapy13. A detailed qualitative assessment allows us to set therapeutic goals and observe changes more accurately. Therefore, the traction test generally assesses the child’s motor maturity and indicates correct development in the third month of life. If the child does it correctly, further motor development should be undisturbed. However, if the child does not perform this test correctly in the third month, the motor performance should be assessed in detail. The qualitative assessment allows us to determine which motor elements are disturbed and to undertake appropriate rehabilitation. As we have shown, other qualitative features indicate whether a child will achieve crawling and sitting down, and other the function of walking. When analyzing the research of Barbosa51, and our previous and this one, it should be emphasized that in infants, an incorrect result of the traction test and a meager score in the qualitative assessment of motor development in supine and prone positions achieved after the third month of life is an argument to refer a child for multi-profile diagnostics. Additionally, an incorrect test result of the traction test, in combination with abnormal eye contact, reduces the likelihood of achieving crawling, sitting down, and walking on time. Children who failed to achieve a given milestone on time but showed the expected quality of movement in the third month stand a chance of achieving it later, and they can be described as delayed in motor development. On the other hand, abnormal quality in the third month of life usually reveals a deeper problem, i.e., impaired motor development.

Diagnostics of motor development performed in the third month of life are early and accurate, thanks to validated tools. The literature describes tests performed at three months to detect children with serious motor problems, such as CP or Autism Spectrum Disorder53,54,55. The traction test alone cannot indicate motor disorders, but it is a good screening test. However, qualitative assessment using the Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment of Motor Development Sheet shows very precisely what area of the body the disorder affects. Thanks to this, the goal of therapy can be determined, and it can be started early to eliminate or at least minimize existing motor abnormalities.

Conclusions

-

(1)

Crawling and sitting down depended on the correct positioning of the hands and lower limbs; social walking was influenced by the qualitative assessment of the position of the lower limbs at three months of age.

-

(2)

The eye contact showed a substantial impact on walking, whereas the correct traction test showed a moderate impact on crawling and sitting down.

-

(3)

The qualitative assessment at the age of three months is highly predictive for the attainment of crawling and sitting down at nine months and social walking latest at 16 months.

-

(4)

Children who did not show the correct traction test nor correct eye contact scored low in the assessment of qualitative elements in the prone and supine position and achieved the milestones later.

Limitations of the study

The study was performed on a relatively severe group of children, many showing motor delay to various degrees. However, on the other hand, none of the studied children have developed child developed cerebral palsy. Studies focused on children at risk of cerebral palsy are needed. Further studies should also be performed on a broader group, with several therapists performing the assessment. A longer follow-up would also be of interest.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files and may be made available upon request from the editorial office. To obtain the necessary data, please email ewagajewska1011@gmail.com or msobieska@ump.edu.pl.

References

Eliks, M., Sowińska, A. & Gajewska, E. The Polish version of the Alberta infant motor scale: cultural adaptation and validation. Front. Neurol. 13, 949720 (2022).

Angulo-Barroso, R. M. et al. Motor development in 9‐month‐old infants in relation to cultural differences and iron status. Dev. Psychobiol. 53, 196–210 (2011).

Eliks, M. & Gajewska, E. The Alberta infant motor scale: A tool for the assessment of motor aspects of neurodevelopment in infancy and early childhood. Front. Neurol. 13, 927502 (2022).

Gajewska, E., Naczk, M., Naczk, A. & Sobieska, M. Dynamics of changes in motor development depending on the quality in the 3rd month of life. Front. Public. Health. 10, 939195 (2022).

Adolph, K. E. & Hoch, J. E. The Importance of Motor Skills for Development. in Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop Series (eds. Black, M. M., Singhal, A. & Hillman, C. H.) vol. 95 136–144 (S. Karger AG, (2020).

Mulder, H., Pitchford, N. J., Hagger, M. S. & Marlow, N. Development of executive function and attention in preterm children: A systematic review. Dev. Neuropsychol. 34, 393–421 (2009).

Flensborg-Madsen, T. & Mortensen, E. L. Predictors of motor developmental milestones during the first year of life. Eur. J. Pediatr. 176, 109–119 (2017).

Leonard, H. C. The impact of poor motor skills on perceptual, social and cognitive development: the case of developmental coordination disorder. Front. Psychol. 7, (2016).

Nguyen, T. N. N. et al. Developmental trajectory of Language from 2 to 13 years in children born very preterm. Pediatrics 141, e20172831 (2018).

Hadders-Algra, M. Early human motor development: from variation to the ability to vary and adapt. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev (2018).

Novak, I. et al. Accurate diagnosis and early intervention in cerebral palsy: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Pediatr. 171, 897 (2017). Early.

Morgan, C. et al. Effectiveness of motor interventions in infants with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 58, 900–909 (2016).

Vojta, V. & Peters, A. The Vojta Principle (Springer-, 2007).

Soska, K. C. & Adolph, K. E. Postural position constrains multimodal object exploration in infants. Infancy 19, 138–161 (2014).

Gajewska, E., Moczko, J., Naczk, M., Naczk, A. & Sobieska, M. Impact of selected risk factors on motor performance in the third month of life and motor development in the ninth month. PeerJ 11, e15460 (2023).

Gajewska, E., Sobieska, M. & Moczko, J. Position of pelvis in the 3rd month of life predicts further motor development. Hum. Mov. Sci. 59, 37–45 (2018).

Gajewska, E., Sobieska, M. & Moczko, J. Qualitative motor assessment allows to predict the degree of motor disturbances. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 18, 2507–2517 (2014).

Gajewska, E. et al. Independent reaching of the sitting position depends on the motor performance in the 3rd month of life. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 19, 201–208 (2015).

Gajewska, E. & Sobieska, M. Qualitative elements of early motor development that influence reaching of the erect posture. A prospective cohort study. Infant Behav. Dev. 39, 124–130 (2015).

Gajewska, E., Sobieska, M., Kaczmarek, E., Suwalska, A. & Steinborn, B. Achieving motor development milestones at the age of three months May determine, but does not guarantee, proper further development. Sci. World J. 2013, 1–11 (2013).

Gajewska, E. et al. Crawl Position Depends on Specific Earlier Motor Skills. JCM 10, 5605 (2021).

Pires, C. D. S., Marba, S. T. M., Caldas, J. P. D. S. & Stopiglia, M. D. C. S. PREDICTIVE VALUE OF THE GENERAL MOVEMENTS ASSESSMENT IN PRETERM INFANTS: A META-ANALYSIS. Rev. Paul Pediatr. 38, e2018286 (2020).

Vojta.com. https://www.vojta.com/en/the-vojta-principle/vojta-diagnostic/postural-responses

Linder, N. et al. A simple clinical test for differentiating physiological from pathological head lag in full-term newborn infants. Eur. J. Pediatrics. 157, 502–504 (1998).

Bentzley, J. P. et al. Kinematic measurement of 12-week head control correlates with 12-month neurodevelopment in preterm infants. Early Hum. Dev. 91, 159–164 (2015).

Kaler, J., Hussain, A., Patel, S. & Majhi, S. Neuromuscular junction disorders and floppy infant syndrome: A comprehensive review. Cureus https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.6922 (2020).

Hellström, B., Knutsson, E. & Wessman, A. The traction reaction in Infancy - Clinical and electromyographic study of normal infants. Neuropediatrics 13, 63–71 (1982).

Vojta, V. Die Zerebralen Bewegungsstörungen Im Säuglingsalte (Internationale Vojta Gesellschaft e.V., 2018).

Levinsen, M., Børresen, M. L., Roos, L., Grønskov, K. & Kessel, L. Causes of poor eye contact in infants: a population-based study. BMC Ophthalmol. 21, 388 (2021).

Çetinçelik, M., Rowland, C. F. & Snijders, T. M. Do the eyes have it?? A systematic review on the role of eye gaze in it?nfant Language development. Front. Psychol. 11, 589096 (2021).

Striano, T., Kopp, F., Grossmann, T. & Reid, V. M. Eye contact influences neural processing of emotional expressions in 4-month-old infants. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 1, 87–94 (2006).

Adolph, K. E. & Robinson, S. R. Motor development. in Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science (ed Lerner, R. M.) 1–45 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA, doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy204. (2015).

Futagi, Y. et al. Eye-Mouth associated movement in the human newborn and very young infant. Pediatr. Neurol. 58, 75–82 (2016).

Bradshaw, J., Shi, D., Federico, A., Klaiman, C. & Saulnier, C. The Pull-to-Sit task: examining infant postural development in autism spectrum disorder. J. Pediatr. 253, 225–231e2 (2023).

Smith, B., Trujillo-Priego, I., Lane, C., Finley, J. & Horak, F. Daily quantity of infant leg movement: wearable sensor algorithm and relationship to walking onset. Sensors 15, 19006–19020 (2015).

WHO Motor Development Study & Onis, M. Windows of achievement for six gross motor development milestones: windows of achievement for motor milestones. Acta Paediatr. 95, 86–95 (2007).

Piper, M. C. & Darrah, J. Motor Assessment of the Developing Infant (Saunders, 1994).

Hidecker, M. J. C. et al. Early predictors and correlates of communication function in children with cerebral palsy. J. Child. Neurol. 33, 275–285 (2018).

Landa, R. J., Gross, A. L., Stuart, E. A. & Bauman, M. Latent class analysis of early developmental trajectory in baby siblings of children with autism: latent class analysis of developmental trajectories. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 53, 986–996 (2012).

Springer-Verlag Neurodevelopmental Disorders. (Vienna, (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/3-211-31222-6

Xiong, Q. L., Wu, X. Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, C. X. & Hou, W. S. Measurement and analysis of human infant crawling for rehabilitation: A narrative review. Front. Neurol. 12, 731374 (2021).

Patrick, S. K., Noah, J. A. & Yang, J. F. Interlimb coordination in human crawling reveals similarities in development and neural control with quadrupeds. J. Neurophysiol. 101, 603–613 (2009).

Yamamoto, S., Matsumura, U., Yeonghee, L. & Tsurusaki, T. Variability in infant crawling with typical development and risk of developmental delay. Early Child. Dev. Care. 193, 979–991 (2023).

Campos, J. J. et al. Travel Broadens Mind Infancy 1, 149–219 (2000).

Bell, M. A. & Fox, N. A. Individual differences in object permanence performance at 8 months: locomotor experience and brain electrical activity. Dev. Psychobiol. 31, 287–297 (1997).

Nan, C. et al. Trajectories and predictors of developmental skills in healthy twins up to 24 months of age. Infant Behav. Dev. 36, 670–678 (2013).

Gould, J. F., Fuss, B. G., Roberts, R. M., Collins, C. T. & Makrides, M. Consequences of using chronological age versus corrected age when testing cognitive and motor development in infancy and intelligence quotient at school age for children born preterm. PLoS ONE. 16, e0256824 (2021).

Khurana, S., Kane, A. E., Brown, S. E., Tarver, T. & Dusing, S. C. Effect of neonatal therapy on the motor, cognitive, and behavioral development of infants born preterm: a systematic review. Develop Med. Child. Neuro. 62, 684–692 (2020).

Flanagan, J. E., Landa, R., Bhat, A. & Bauman, M. Head lag in infants at risk for autism: A preliminary study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 66, 577–585 (2012).

Pineda, R. G. et al. Head lag in infancy: what is it telling Us? Am. J. Occup. Therapy. 70, 7001220010p1–7001220010p8 (2016).

Barbosa, V. M., Campbell, S. K., Smith, E. & Berbaum, M. Comparison of test of infant motor performance (TIMP) item responses among children with cerebral palsy, developmental delay, and typical development. Am. J. Occup. Therapy. 59, 446–456 (2005).

Igarashi, M. Floppy infant syndrome. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 6, 69–90 (2004).

Morgan, C. et al. The pooled diagnostic accuracy of neuroimaging, general movements, and neurological examination for diagnosing cerebral palsy early in High-Risk infants: A case control study. J. Clin. Med. 8, 1879 (2019).

Allermo Fletcher, A. et al. Partnering early to provide for infants at risk of cerebral palsy (PĒPI ARC): protocol for a feasibility study of a regional hub for early detection of cerebral palsy in Aotearoa new Zealand. Front. Pediatr. 12, 1344579 (2024).

Gajewska, E., Sobieska, M. & Samborski, W. Associations between manual abilities, gross motor function, epilepsy, and mental capacity in children with cerebral palsy. Iran. J. Child. Neurol. 8, 45–52 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S., M.S., E.G. wrote the main manuscript text and M.S., E.G.,A.Ch., J.M., M.M. prepared figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gajewska, E., Surowińska, J., Chałupka, A. et al. The qualitative motor assessment at three months allows a better prognosis than the traction test. Sci Rep 15, 15035 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98118-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98118-5