Abstract

To enhance bearing fault diagnosis performance under various operating conditions, this paper proposes a hybrid approach based on generative adversarial networks (GANs), transfer learning, wavelet transform time-frequency representations, asymmetric convolutional networks, and the multi-head attention mechanism (MAC-MHA). Firstly, GANs are utilized to generate new bearing fault data to meet the model’s training requirements. Then, wavelet transform is applied to convert the bearing vibration signals into time-frequency representations, capturing the temporal evolution of frequency components. Next, an improved asymmetric convolutional network (MAC-MHA), combined with the multi-head attention mechanism, is employed to enhance the focus on key time-frequency features, further improving fault diagnosis accuracy. Considering the differences in operating conditions, transfer learning techniques are applied to facilitate knowledge transfer from the source domain to the target domain, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization ability. Experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed method under various operating conditions. Finally, the proposed hybrid fault diagnosis approach is validated using the PADERBORN and CWRU datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the growing complexity of large industrial equipment, intelligent fault diagnosis has become essential for ensuring the safety and reliability of industrial systems1,2,3. Achieving accurate fault diagnosis is crucial for maintaining operational efficiency and minimizing downtime4,5,6,7,8.

Rotating machinery systems are vital components in industrial applications. Bearings, as critical elements of these systems, play an indispensable role in ensuring the proper functioning of machinery9. Fault diagnosis methods for these systems are typically classified into model-based and data-driven approaches10. Model-based methods require extensive prior knowledge to develop fault mechanism models, which can be challenging due to the diverse operating conditions and complex working environments of rotating machinery11,12 . In contrast, data-driven methods, which do not require prior fault knowledge, enable timely fault diagnosis by analyzing sensor data13,14 . In recent years, learning-based approaches, such as deep learning and reinforcement learning, have gained widespread application in fault diagnosis15,16,17,18

Representation learning, an important subset of learning algorithms, includes methods such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs)19,20, generative adversarial networks (GANs)21,22, transfer learning23, and manifold learning24. This approach transforms raw features into formats that machines can effectively process, offering enhanced reliability and interpretability. Representation learning establishes a link between the vast sensory data generated by industrial equipment and the valuable features required for fault diagnosis. This connection presents opportunities for uncovering hidden patterns in large-scale data. In recent years, representation learning has gained increasing attention in the field of intelligent bearing fault diagnosis.

To tackle the challenges of insufficient training samples and the high cost of parameter tuning for bearing fault diagnosis under various operational conditions, Song et al.25 proposed an integrated method combining optimized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with bidirectional long short-term memory networks (BiLSTM). This approach enhances training efficiency by optimizing hyperparameters through an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm and utilizes transfer learning to boost fault diagnosis accuracy. Dong et al.26 addressed the non-stationary and non-linear nature of rolling bearing fault signals by introducing an intelligent fault diagnosis framework that integrates empirical wavelet transform (EWT) and one-dimensional self-attention-enhanced CNNs (1D-ISACNN). This framework significantly improves fault classification accuracy and robustness. Ruan et al.27 proposed a physics-guided CNN parameter design method to overcome the lack of theoretical guidance and inefficiency in setting CNN parameters for bearing fault diagnosis. By analyzing the periodicity and attenuation characteristics of bearing fault signals, this method optimizes the input size and convolution kernel size of CNNs, enhancing both diagnostic accuracy and efficiency. Jia et al.28 introduced a Gram time-frequency enhancement CNN (GTFE-Net) combined with a Gram noise reduction (GNR) strategy to address the interference of irrelevant noise in vibration signals. This method improves the accuracy and robustness of fault feature extraction in bearing fault diagnosis. Wang et al.29 proposed an attention-guided joint learning CNN (JL-CNN) to address vibration signal denoising and fault diagnosis in mechanical systems. By integrating fault diagnosis (FD-Task) and signal denoising tasks (SD-Task) into an end-to-end architecture, this model demonstrates excellent noise robustness under challenging and unknown noise conditions. Wang et al.30 addressed the limitations of single-mode signals in bearing fault diagnosis by proposing a fusion-based method utilizing vibration-acoustic data and 1D-CNNs. This approach, which combines accelerometer and microphone sensor signals, enhances both the accuracy and robustness of fault diagnosis. Chen et al.31 introduced an automatic feature learning model, based on multi-scale CNNs and long short-term memory networks (MCNN-LSTM), to overcome the challenges of expert knowledge dependence, time consumption, and noise interference in feature extraction. The model directly extracts features from raw vibration signals, improving diagnostic accuracy and robustness. Zhao et al.32 addressed data imbalance and variable working conditions in intelligent rolling bearing fault diagnosis by proposing a solution based on normalized CNNs. Wang et al.33 developed a novel intelligent fault diagnosis method using symmetric point graph (SDP) representations and squeeze-excitation CNNs (SE-CNN), aiming to enhance the visualization and automatic feature extraction capabilities in bearing fault diagnosis. Peng et al.34 proposed an improved method called Statistical Matrix Form (SMF) to reduce traffic overhead in unstructured peer-to-peer networks. This method selectively sends query messages based on the capabilities of neighboring nodes, improving search efficiency and reducing traffic overhead. To address the intelligent fault diagnosis of high-speed train wheelset bearings under variable load, speed, and noisy environments, Peng et al.35 introduced a novel deep one-dimensional CNN (Der-1DCNN) model. This model enhances fault feature extraction and network generalization performance through residual learning and wide convolution kernels. Eren et al.36 proposed a universal intelligent fault diagnosis system for high-speed train wheelset bearings in noisy environments. This system, based on a compact adaptive 1D CNN classifier, automatically extracts features from raw sensor data and performs efficient classification.

This paper presents a novel method that integrates signal processing and deep learning techniques, overcoming some limitations of traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in practical applications. The proposed approach combines Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Transfer Learning, and Empirical Wavelet Transform (EWT) Empirical Wavelet Transform (EWT) with an enhanced multi-head attention mechanism and asymmetric convolutional networks, thereby improving model performance and training efficiency. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

-

(a)

The time-frequency representations obtained through continuous wavelet transform effectively capture the local features of the signal in both the time and frequency domains, facilitating the analysis of instantaneous frequency variations and fault characteristics of non-stationary signals.

-

(b)

A new Multi-Head Attention Asymmetric Convolutional Network (MAC-MHA) is introduced, which employs asymmetric convolution blocks for feature extraction. After the convolution layers, a multi-head attention mechanism is incorporated, enabling the model to focus on key areas of the image and capture both local and global relationships across different representational spaces.

-

(c)

A Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) is employed to generate synthetic bearing fault data, enhancing the sample size for bearing fault categories and addressing the data imbalance issue.

-

(d)

The bearing fault diagnosis across varying working conditions is facilitated through transfer learning. By transferring a model pre-trained on the source domain, fault diagnosis for different bearing types can be achieved in multiple target domains. The model is fine-tuned using a small subset (10%) of data from the target domain, allowing it to adapt effectively to the specific fault conditions of the target domain. This approach reduces the dependence on large datasets and enables effective fault diagnosis with limited sample sizes.

Proposed integrated fault diagnosis scheme based on representation learning

Overview

The framework of the proposed ensemble multi-task intelligent bearing fault diagnosis scheme, based on representation learning under imbalanced sample conditions, is illustrated in the Fig. 1. In the context of bearing fault diagnosis in the source domain using the Modified Asymmetric Convolutional Network with Multiple Attention Mechanisms (MACN-MHA), the process can be divided into two main stages: offline training and online detection.

During offline training, the original bearing data is first used to train a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), which generates new bearing fault data. This newly generated data is combined with 70% of the original data to form the training set. Continuous wavelet transform is then applied to convert the vibration signals into time-frequency representations, which are used for offline training. For online diagnosis, real-time operational data is transformed into time-frequency representations through continuous wavelet transform and subsequently input into the pre-trained MACN-MHA network. In the case of bearing fault diagnosis under varying operating conditions, the model trained on the source domain is transferred to the target environment. Fine-tuning the model with a small amount of target data enables it to adapt to the features of the target environment. Consequently, the model trained on bearing operational data is successfully transferred, and fault diagnosis under different operating conditions can be performed using only a small sample (10%).The overall architecture of the proposed model is shown in Fig. 1

MACN-MHA network based on representation learning

Asymmetric Convolutional (AC) networks are a type of convolutional neural network designed with asymmetric convolution blocks. In the AC network, each convolutional layer consists of three asymmetric convolution blocks (ACBs) with kernel sizes of 3 \(\times\) 3, 1 \(\times\) 3, and 3 \(\times\) 1, with their outputs combined through summation37,38,39. To mitigate the impact of noise signals, the multi-head attention mechanism is employed to weight and aggregate features from different regions40. This ensemble approach introduces an enhanced non-stacked asymmetric convolutional neural network, which incorporates a asymmetric convolutional layer and a multi-head attention mechanism (MACN-MHA). Drawing inspiration from asymmetric convolution networks in image processing, the proposed MACN-MHA offers three key improvements:

Wavelet transform is applied to the bearing data for initial noise reduction, facilitating the more accurate identification of distinct events and anomalies in the signal.

The multi-head attention mechanism is integrated into the asymmetric convolutional layer neurons, enabling stronger inter-layer relationships and promoting feature fusion across layers.

Dropout layers are incorporated between the connection layers, effectively preventing overfitting during model training.

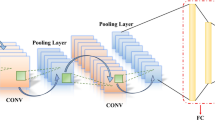

The structure of the MAC-MHA model is illustrated in Fig. 2. MAC-MHA consists of wavelet layers, asymmetric convolutional layers, pooling layers, multi-head attention (MHA) layers, dropout layers, and fully connected layers. The detailed description of each component is as follows:

Continuous wavelet transform layer

The Asymmetric convolutional structure of Asymmetric Convolutional Neural Networks (ACNs) is typically designed to process 2-D or 3-D input data. In contrast, the diagnostic performance of ACNs on one-dimensional inputs is suboptimal. Therefore, it is necessary to convert 1-D vibration signals into 2-D or even higher-dimensional representations for ACNs. As a time-frequency domain transformation technique, the Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) effectively converts 1-D vibration signals into 2-D time-frequency spectrograms, which can then be directly utilized by the asymmetric convolutional layers. For a 1-D vibration signal sequence x(t), the CWT of these signals is expressed as follows:

In the Eq. 1, x(t) represents the input signal, denoting the signal value at time t.The parameters is the scale factor, which controls the width of the wavelet. A larger s corresponds to a lower frequency (wider time window), while a smaller s corresponds to a higher frequency (narrower time window). The parameter \(\tau\) is the translation factor, indicating the position of the wavelet along the time axis. The term \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{s}}\) is the normalization factor, ensuring that the energy of the wavelet transform remains invariant across different scales. \(\psi (t)\) is the mother wavelet (basis function), where \(\psi\) denotes the wavelet function used for local feature extraction from the signal. The differential element \(d\tau\) represents the integration over the time translation parameter \(\tau\). The wavelet function selected in this study is the complex Gaussian wavelet, which is expressed in Eq. 2 . In this equation, \(\psi (t)\) is the complex Gaussian wavelet basis function, representing the mother wavelet at timet. The parameter \(\omega _0\) denotes the center frequency of the wavelet, determining its frequency characteristics. This parameter is commonly used to control the high-frequency components of the wavelet and is typically set as a constant. The variable t represents time, indicating the position of the wavelet along the time axis. The term \(e^{i \omega _0 t}\) represents the complex sinusoidal component, which governs the oscillatory behavior of the wavelet. The factor \(e^{-\frac{t^2}{2}}\) is the Gaussian window function, which defines the localization properties of the wavelet, ensuring that it is finite and concentrated in the time domain.

Asymmetric convolution Kernel

In this study, we propose the use of an asymmetric convolution kernel to replace the traditional symmetric convolution kernel in the convolutional layer. This novel asymmetric design enables the model to more flexibly capture feature information from different directions. Compared to symmetric kernels, asymmetric convolution kernels can achieve equivalent or even superior performance with fewer computations.

Focusing on the commonly used 3 \(\times\) 3 convolution in modern CNN architectures, we substitute each 3 \(\times\) 3 convolutional layer (and the associated batch normalization layer, if present) with an Asymmetric Convolution Block (ACB). The ACB consists of three parallel layers with kernel sizes of 3 \(\times\) 3, 1 \(\times\) 3, and 3 \(\times\) 1. Following standard practices in CNNs, batch normalization is applied to each layer in the ACB branches, and the outputs of these branches are summed to form the final output. Notably, ACNet can be trained with the same configuration as the original model, without the need for additional hyperparameter adjustments.

where \(W_sq\in \mathbb {R}^{K\times K}\)is the square convolution kernel, and \(b_sq\) is the bias term. where \(W_{hor}\in \mathbb {R}^{1\times K}\) is the horizontal convolution kernel, and \(b_{hor}\) is the bias term. where \(W_{ver}\in \mathbb {R}^{K\times 1}\) is the vertical convolution kernel, and \(b_{ver}\) is the bias term.

Pooling layer

The pooling layer serves the function of downsampling, which reduces data dimensionality and computational complexity while preserving essential feature information. Pooling is generally categorized into max pooling and average pooling. In max pooling, downsampling is achieved by selecting the maximum value within a local region, whereas in average pooling, the average value within a local region is selected.

The computation formula for max pooling is:

P is the size of the pooling window (e.g., \(2\times 2)\) ). X is the input data, where \(X_{i,j,d}\) represents the pixel value of the (i, j) input channel at position d. Y is the output pooled feature map, where \(Y_{i,j,d}\) denotes the pooling result at position d in the (i, j)output channel.

Multi-head attention mechanism

The multi-head attention mechanism is an extension of the attention mechanism, primarily designed for natural language processing (NLP) and sequence data analysis. It extracts diverse feature information by utilizing multiple parallel attention heads. Each attention head computes the relationships between the query (Q), key (K), and value (V) to capture crucial information. By enabling parallel computation across multiple heads, the model can simultaneously focus on different segments of the sequence.

Q is the query matrix, K is the key matrix, and V is the value matrix. \(\cdot d_k\) is the dimension of the keys. softmax is the normalization function used to compute the attention weights. Equation 10 represents the multi-head attention mechanism, while Eq. 11 defines the calculation formula for each head.\(\cdot\) \(W_i^Q, W_i^K, W_i^V\) are the weight matrices for the query, key, and value in the iii-th head, respectively. \(\cdot\) \(W^{O}\) is the weight matrix for the linear transformation of the concatenated output

Dropout layer

The dropout layer serves the purpose of randomly “dropping” a subset of neurons during training to mitigate overfitting. By reducing the dependence between nodes in the network, dropout enhances the model’s generalization ability, thereby fostering more robust learning.

where \(\textbf{r}\)is a binary random vector, with \(r_i\in \{0,1\}\), and \(\mathbb {E}[r_i]=p\) takes the value 0 with probability pand the value 1 with probability 1\(1-p\)).

The fully connected (FC) layer

The fully connected (FC) layer connects all outputs from the previous layer to each neuron in the current layer, performing a linear transformation to generate the final output. It is commonly employed as the final layer in classification or regression tasks, where it transforms features from preceding layers into target labels.

The computation for a fully connected layer is expressed as follows:

where:

\(\cdot W\in \mathbb {R}^{m\times n}\) is the weight matrix.

\(\cdot\) \(b\in \mathbb {R} ^m\) is the bias vector.

Small-sample bearing fault diagnosis based on generative adversarial networks

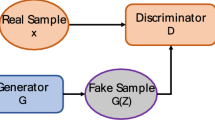

On this basis, the mixed data generated by the GAN model from the source domain’s initial dataset serves as the source domain, while different datasets are used as the target domain. At the same time, generative adversarial networks (GANs) are also an important representation learning method. Through adversarial training between the generator and discriminator, GANs can generate samples that match the distribution of real data.41

In the practical application of bearing monitoring, vibration signal data may be incomplete or missing due to sensor faults, sampling issues, or other factors. GANs can be used to supplement this missing data, enabling the model to use more information during training and avoid performance degradation caused by missing data.42 In this context, the mixed data generated by the GAN model from the source domain’s initial dataset serves as the source domain, while different datasets are used as the target domain. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) are a significant method for representation learning. Through adversarial training between the generator and discriminator, GANs can generate samples that align with the distribution of real data41. In the practical application of bearing monitoring, vibration signal data may be incomplete or missing due to sensor faults, sampling errors, or other factors. GANs can help supplement the missing data, allowing the model to utilize more information during training and prevent performance degradation caused by incomplete data42. Additionally, dimensionality reduction techniques such as t-SNE and PCA were employed to visualize the generated data and real data in a low-dimensional space, providing an intuitive demonstration of the distribution overlap between the two. Experimental results indicate that the synthetic data exhibits high similarity to real data across most features, thus providing effective support for data augmentation.43

While GANs help address data imbalance, excessive or low-quality synthetic data can cause overfitting. To mitigate this, we assessed data similarity using statistical analysis (e.g., t−SNE, PCA) and applied regularization techniques (L2, Dropout, early stopping) to improve generalization.44,45,46 Additionally, we used incremental learning to gradually introduce synthetic data, preventing premature reliance. Future work includes enhancing generative models with adversarial regularization and diversity-improving techniques. These strategies effectively reduce overfitting and improve real−data generalization47,48.

The formula for the GAN model is defined as follows: Generator’s Loss Function: The generator’s objective is to produce fake data that maximizes the discriminator’s probability of classifying it as “real.” The loss function for the generator is given by:

where z represents random noise sampled from the noise distribution \(p_z(z)\)), G(z) is the fake data generated by the generator, and D(x) is the output of the discriminator, denoting the probability that the data x is real. The generator seeks to minimize this loss, thereby increasing the likelihood that the discriminator classifies the generated data as “real.” Discriminator’s Loss Function: The discriminator’s objective is to accurately classify both real and fake data. The loss function for the discriminator is defined as:

The first term represents the loss for classifying real data, while the second term accounts for the loss for classifying fake data. The discriminator aims to maximize this loss function, aiming to classify real data as real (D(x) close to 1) and fake data as fake (D(G(z)) close to 0).The issue of insufficient training data can be addressed by generating new samples to augment the dataset.

Bearing fault diagnosis under different operating conditions based on transfer learning

Transfer learning, a key method in representation learning, involves transferring a model trained on a source task to a target task to enhance the generalization ability of the trained model49,50,51. The model-based approach to transfer learning is a subfield of transfer learning, where source and target tasks share similar feature representations. This method transfers a model pre-trained on the source task to the target task, enabling the sharing of model parameters and thereby improving the model’s performance.52,53,54

To further validate the effectiveness of transfer learning, we also compared it with existing domain adaptation methods, such as the Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) alignment approach. These methods reduce the discrepancy between the source and target domains by aligning their feature distributions, thereby improving the model’s performance on the target domain55,56. We compared the transfer learning method with traditional machine learning models and existing domain adaptation methods. Specifically, we conducted experiments using the source domain (e.g., the PADERBORN dataset) and the target domain (e.g., the CWRU dataset). The base model for transfer learning was trained on the source domain, followed by fine-tuning with target domain data to adapt to the specific distribution of the target domain. During fine-tuning, we employed a strategy where the lower-layer feature extractors were frozen and only the higher-layer classifiers were fine-tuned57, to reduce the reliance on target domain data. Through a comparative analysis of the experimental results, the transfer learning method significantly outperformed traditional machine learning and standard deep learning models. On the target domain data, the transfer learning approach achieved notable improvements across multiple metrics, such as accuracy and F1 score, especially in scenarios with data imbalance and substantial domain discrepancies, where its advantages were particularly pronounced58. Moreover, compared to existing domain adaptation methods, the transfer learning approach also demonstrated clear benefits in terms of reduced training time and enhanced model generalization.

The formulas for the transfer model are shown in Table 1.

Let \(\mathscr {M}\text {source}\) denote the source model. The function f represents the model function, typically a neural network or machine learning model. \(\mathscr {D}\text {source}\) refers to the dataset from the source domain, used for training the source model, while \(\theta _\text {source}\) represents the parameters of the source model. Similarly, \(\mathscr {M}\text {target}\) denotes the target model, and \(\mathscr {D}\text {target}\) refers to the dataset from the target domain, used for training the target model. The parameters of the target model, denoted as \(\theta _\text {target}\), are initially set to \(\theta _\text {source}\) from the source model.

The cross-entropy loss function is denoted by \(\mathscr {L}\text {CE}\), and N is the number of samples. The parameters being fine-tuned are represented by \(\theta \text {finetune}^{(t)}\), with the gradient of the loss with respect to these parameters denoted as \(\nabla _{\theta _\text {finetune}} \mathscr {L}\). The parameters of the frozen layers are represented by \(\theta _\text {frozen}\), and \(\theta _\text {target}^{(t)}\) denotes the current value of the target model parameters.

The loss function for the target task is represented as \(\mathscr {L}\text {target}\), while \(\mathscr {C}\text {target}\) and \(\mathscr {C}\text {source}\) denote the convolutional layer weights of the target and source models, respectively. The newly initialized output layer parameters of the target model are denoted by \(\theta \text {target}^{(\text {new})}\). Finally, \(\hat{y}\) represents the predicted value of the target model, and Y denotes the true label of the target model.

In this paper, we use transfer learning to address limited target domain data. A base model is trained on source domain data and fine-tuned on 10% of the target domain data. This choice is based on the high feature similarity between the source (e.g., PADERBORN dataset) and target domains (e.g., CWRU dataset), which allows effective transfer. Previous research shows that fine-tuning with small amounts of target domain data can enhance performance when domain similarity is high51. Fine-tuning 10% of the target domain data is a reasonable choice that avoids overfitting while ensuring sufficient domain adaptation. Given the scarcity of fault data in industrial applications, fine-tuning with a small percentage reduces data needs and improves computational efficiency. To validate this, we compared model performance across different target domain data ratios (5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%). Results show that 10% fine-tuning significantly enhances performance, with further increases having minimal effect. The experimental results, as shown in Fig. 3. This supports the 10% fine-tuning ratio as both effective and efficient. We also explored transfer learning adaptability by testing different strategies, including freezing layers and fine-tuning all layers. Freezing early layers and fine-tuning higher-level classifiers provided good adaptation with faster training. Fine-tuning all layers improved performance but increased training time and computational cost. In data-scarce scenarios, fine-tuning higher layers offers a good balance between performance and efficiency.

Although transfer learning can effectively transfer knowledge from the source domain to the target domain, thereby reducing the reliance on large amounts of labeled data in the target domain, it may encounter certain limitations when applied to entirely new datasets beyond PADERBORN and CWRU. These new datasets may exhibit significant differences from PADERBORN and CWRU in terms of signal noise, sampling frequency, sensor configuration, data quality, and preprocessing requirements, which can result in reduced model adaptability in the new environment, thereby affecting feature extraction and overall model performance. For instance, the new dataset may contain different types of noise (such as environmental noise, electrical interference, etc.) that were not sufficiently present in the source domain data, which could lead to the extracted features no longer being representative for the new dataset. Moreover, differences in sampling frequency could affect the model’s ability to capture time-domain features, particularly when performing time-frequency analysis on vibration signals. Variations in sensor configurations and data acquisition methods may lead to changes in the signal’s dynamic range and frequency response, thus impacting feature stability and the model’s generalization capability. Therefore, although transfer learning can expedite the model’s adaptation process in the target domain, additional domain adaptation techniques or target domain fine-tuning strategies may be required to overcome these challenges when dealing with new datasets exhibiting significant differences.

Selection and motivation of the proposed techniques

The combination of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), transfer learning, wavelet transform, Asymmetric Convolutional Networks (AC-Net), and Multi-Head Attention Mechanism (MAC-MHA) proposed in this paper is based on their effectiveness in fault diagnosis tasks, as well as their proven theoretical and experimental benefits. Firstly, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have been widely used to address the small sample problem, particularly in industrial fault diagnosis. GANs enhance the model’s generalization ability by generating synthetic samples, thereby improving classification performance59. Secondly, transfer learning has been demonstrated to effectively address cross-domain data issues, particularly in fault diagnosis under varying operating conditions. By transferring existing knowledge, transfer learning reduces the data requirements of the target domain and improves the accuracy of diagnostic models60,61. Furthermore, wavelet transform, due to its ability to extract multi-scale features from signals, is extensively applied in vibration signal analysis and is especially effective for detecting various types of faults62. Asymmetric Convolutional Networks (AC-Net), through the design of asymmetric convolution structures, effectively extract local features and improve diagnostic capabilities in complex fault scenarios63. Lastly, the Multi-Head Attention Mechanism (MAC-MHA) has demonstrated outstanding ability in handling complex sequential data. It captures multi-level feature dependencies, enhancing the model’s discriminative power across multiple fault modes64. Therefore, the selection of these techniques in this paper is aimed at integrating their respective advantages to construct an efficient model capable of addressing fault diagnosis challenges under different operating conditions.

Case study I: PADERBORN

Dataset description

The dataset used to validate the proposed model was provided by the Chair of Design and Drive Technology, Paderborn University, Germany. As shown in Fig. 4, the test rig comprises an electric motor, a torque-measurement shaft, a rolling bearing test module, a flywheel, and a load motor. A piezoelectric accelerometer (model PCB 336C04) is mounted on the rolling bearing module, and a current transducer (model LEM CKSR 15-NP) is placed between the motor and the inverter externally65. An A/D converter is employed to collect the vibration and current signals during the test. A total of 32 bearing sets were tested, each exhibiting different damage types and fault levels, which were classified into four states: inner ring fault, outer ring fault,Inner ring outer ring compound failure, and healthy65. The experiments were conducted under three distinct conditions, labeled A, B, and C, as listed in Table 1. Condition A had a speed of 1500 rpm, a load torque of 0.7 N.m, and a radial force of 1000 N, while the other two conditions involved reducing the load torque to 0.1 N.m and the radial force to 400 N, respectively. For each condition, the test was repeated 20 times, and the current and vibration signals were recorded at a sampling rate of 64 kHz for 4 seconds per trial.

In summary, the key characteristics of this dataset are as follows: it synchronously records high-resolution, high-sampling-rate motor current and vibration signals for 26 damaged bearing conditions and 6 healthy (non-damaged) states. The measurements include data on rotational speed, torque, radial load, and temperature, across four distinct operating conditions. Each setting consists of 20 measurements, each lasting 4 seconds, with the data stored in MATLAB files. The filenames include the codes for the operating conditions and a four-digit bearing code (e.g., N15\(_{M07}\)F10\(_{KA01}\)1.mat). A standardized fact table, as outlined in Section 2 (for classification - bearing damage classification), is used to systematically describe the bearing damage states.

Feature extraction

To address the Imbalanced Sample Condition, the extracted data is fed into a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). Through adversarial training between the generator and discriminator, new data is generated and mixed with 70% of the original domain data to create the model’s training dataset. To better represent the status of the bearing during operation, feature extraction is performed from the time-frequency domain. The Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT), a tool for decomposing non-stationary signals, is used to convert vibration data into time-frequency spectrograms. By convolving the signal with the wavelet, the response of the signal at various time instances and scales is captured.

In this study, vibration data is analyzed from the time, frequency, and time-frequency domains for feature extraction. The maximum and minimum values in the time domain, along with other time-domain features, are used to describe the bearing’s health condition. Additionally, when a bearing fault occurs, the energy in specific frequency bands associated with the fault may exhibit significant changes. As a result, the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) method66 is applied to extract frequency domain features. In total, seven features are extracted from the time and frequency domains to characterize the bearing vibration data, as shown in the feature calculation formula Table 2.

Where L denotes the length of the vibration signal, \(x_{i}\) is the amplitude of the signal at the i-th time instant, K is the length of the frequency spectrum, \({n}s_{j}\) represents the amplitude of the signal’s spectrum after FFT, and \(f_{j}\) is the corresponding frequency.

Regarding time-frequency domain features, Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) is utilized as a tool for decomposing non-stationary signals. It transforms vibration data into a time-frequency representation, enabling the analysis of the signal’s response at different time instances and scales through convolution with the signal. In this study, the complex Gaussian wavelet is chosen as the mother wavelet, and the db3 wavelet is used to decompose the vibration data into three wavelet packets, yielding 8 sub-signals within different frequency bands.67,68 Furthermore, eight time-frequency features are extracted based on the wavelet transform coefficients. In summary, a total of 22 features are extracted across the aforementioned three domains (time, frequency, and time-frequency) to characterize the health status of the bearing in all directions of vibration. It should be noted that the sampling frequency is 12,000 Hz, and the signal duration is 60 seconds. A bearing vibration sample of 0.125 seconds duration is used as a single sample, with each sample containing 1,024 data points. Afterward, the data is transformed into a time-frequency representation .

Experimental result

Fault detection based on MAC-MHA

During the offline training phase, 70% of the bearing fault data is combined with data generated by the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to serve as input for training the MAC-MHA model. The bearing operates under three different rotational speed conditions, with each condition containing 480 samples, resulting in a total of 1,440 data samples.

The hyperparameter configurations for MAC−MHA are summarized in Table 3. To validate the rationale behind the selection of hyperparameters, we conducted ablation experiments by adjusting the values of embed\(_{dim}\), num\(_{heads}\), and learning\(_{rates}\), and evaluated their impact on the model’s performance. These experiments were carried out using standard benchmark datasets, such as PADERBORN and CWRU, with the validation loss curves serving as the evaluation metric. By comparing the performance under different hyperparameter configurations, we found that the configuration with embed\(_{dim}\)=16 and num\(_{heads}\)=4 achieved the best performance in addressing complex fault diagnosis tasks. Specifically, the configuration of embed\(_{dim}\)=16 and num\(_{heads}\)=4 offered a balance between maintaining relatively low computational cost and significantly enhancing the model’s accuracy and robustness. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 5.

One advantage of this method is that it enables the assignment of varying weights to the neurons in the bottleneck layer, thereby enhancing reconstruction performance. For the 1,440 training samples, to demonstrate the interpretability of this representation learning approach, Fig. 6a and b show a comparison of the weight visualizations in the fully connected layer, with and without the Multi-Head Attention (MHA), as presented in Fig. 6. To better represent the experimental results, maximum-minimum normalization is applied. It can be observed that the introduction of MHA alters the data distribution of the fully connected layer neurons, concentrating the weights at significant positions. The visualization of intermediate layers is a key contribution to interpretable representation learning. Consequently, the performance of the unsupervised fault detection model for each fault category is validated with a total of 1,440 samples across three different rotational speed conditions. The experimental results for the bearing fault detection task based on MAC-MHA are presented in Fig. 7.

Specifically, Fig. 7a–d present the results for noramal , outer race failure,inner race failure, and combined failure, respectively. Detection accuracy serves as the evaluation metric, where higher accuracy indicates better detection performance. The accuracy test results are summarized in Table 4. From both Table 4 and Fig. 7, it is evident that the MAC-MHA, as part of the proposed integrated approach, demonstrates strong fault detection performance under supervised conditions.

Few-shot bearing fault classification based on generative adversarial networks (GANs)

For fault classification in the integrated approach, the hyperparameter configuration of the fully connected network is provided in Table 5. Given the limited availability of fault samples in practical scenarios, a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) is employed to generate synthetic bearing fault data, which is then combined with 70% of the original samples for training. Specifically, 3910 Time-frequency representation(TFR) samples are used for training, while 563 samples TFR are used for validation. The confusion matrix and t-SNE visualization for healthy operation and the three fault classifications is shown. As illustrated in Figs. 8 and 9, the proposed CWT-MAC-MHA-NN approach effectively classifies different types of few-shot faults. For clarity, Fault 1 through Fault 4 represent inner race fault, ball fault, outer race fault, and combined fault, respectively.

Table 6 presents a comparative analysis of fault classification results using various machine learning and deep learning methods, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), CNN with Attention Mechanism (CNN-Attention), 1D Convolutional Neural Networks combined with Long Short-Term Memory Networks (TCN−LSTM), Convolutional Recurrent Networks combined with Long Short−Term Memory Networks (CNN−LSTM), and CNN on the RDER dataset. It is noteworthy that all methods were trained using 10% of the total sample.

Bearing fault detection and diagnosis under different operating conditions based on transfer learning

The mixed dataset, comprising data generated through Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) training and the original PADERBORN dataset, serves as the source domain, while datasets(CWRU) from different operating conditions are used as the target domain. Initially, the MAC-MHA model is trained on the source domain and subsequently transferred to the target domain. Fine-tuning is performed using 10% of the target domain data to adapt the model to the target environment’s features. The results of bearing fault detection and diagnosis under varying operating conditions through transfer learning are presented in Figs. 10 and 11 Features 1-5 correspond to the following fault types: rolling element fault, inner race fault, outer race fault in the relative direction, outer race fault in the orthogonal direction, and outer race fault in the central direction. As shown in these figures, the proposed integrated approach effectively identifies fault data across different operating conditions. Specifically, after fine-tuning the transfer model, the accuracy of bearing fault diagnosis under diverse conditions reaches 97.52%. The ability to perform fault diagnosis under various conditions using transfer learning is notable and has been relatively underexplored in existing research. In this context, the proposed integrated approach introduces a representation learning-based recognition method with high accuracy.

Case study II: CWRU bearing dataset

Dataset description and feature extraction

The practical bearing data provided by Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) is utilized to validate the proposed approach. The experimental setup consists of a driven motor, a load motor, an accelerometer, a torque transducer, and a bearing seat, as shown in Fig. 12. The bearings used in the experiment are deep groove ball bearings, specifically the 6205-2RS JEM and 6203-2RS JEM models. Notably, the faults are induced in the bearings using electrical discharge machining (EDM). The faults are classified based on their location as follows: inner race fault, ball fault, centered outer race fault, orthogonal outer race fault, and opposite outer race fault. The healthy bearing data and the faulty data with a 0.007-inch diameter defect imposed on the 12 k drive end are used to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Due to the two measurement channels for the bearing data, vibration signals in two directions can be obtained. A large amount of data is generated by the test rig when the bearing is in a healthy state, with a sampling frequency of 12,000 Hz. Each sample consists of 512 data points. Therefore, a total of 928 fault samples are obtained under four different loading conditions. For each direction, 22 features are extracted, including time-domain, frequency-domain, and time-frequency-domain features. Consequently, a total of 44 features are obtained from the two measurement channels.

Experimental result

Fault detection based on generative adversarial networks (GAN) and CWT-MAC-MHAC:

During the offline training phase, the input to the CWT-MAC-MHAC network consists of 928 samples generated by the GAN and 70% of the original data, totaling 4599 Time-frequency representation(TFR) fault samples.Correspondingly, for each fault type, there are a total of 1149 TFR samples under four different load conditions used to validate the performance of the unsupervised fault detection model. On this basis, the experimental results of the bearing fault detection task based on MACB-MHA are shown in Fig. 13. In detail, the sub-graphs(a-e) show the results for inner ball fault,race fault, , centered outer race fault, orthogonal outer race fault, and opposite outer race fault,inner race fault respectively.The testing results of accuracy are summarized in Table 7. As shown in Table 7 and Fig. 13, the proposed CWT-MACB-MHA demonstrates excellent fault detection performance.

Fault classification based on data generated by generative adversarial networks (GAN)

The hyperparameter configuration of the neural network in this section largely aligns with that presented in Table 5. Given that the CWRU dataset encompasses six operational conditions, the number of neurons in the final layer is set to six. For each operational condition, both the generated and 70% of the original samples are used for training. Specifically, 4599 TFR samples are used for training, and 810 TFR samples are used for testing. Figures 14 and 15 presents the confusion matrix and t-SNE visualization for the five fault classifications. For clarity, Faults 1 through 5 correspond to the following conditions: inner race fault, ball fault, central outer race fault, orthogonal outer race fault, and opposite outer race fault, respectively.

The CWT-MACB-MHA-NN model effectively classifies different faults. Furthermore, Table 8 compares several machine learning and deep learning methods applied to the CWRU dataset. As shown in Table 8, the proposed CWT-MACN-MHA-C model demonstrates high accuracy under few-shot learning conditions.

Bearing fault diagnosis under different operating conditions based on transfer learning

For bearing fault diagnosis under varying operating conditions, transfer learning enables the model trained on the source domain task to be transferred to the target domain task, thereby improving the generalization ability of the trained model. The fault diagnosis results under different operating conditions, after transferring the model, are presented in Figs. 16 and 17. As shown in Figs. 16 and 17, the proposed integrated approach effectively identifies fault data across different operating conditions. These experimental results have important implications for bearing fault recognition under diverse operational scenarios.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a bearing fault diagnosis framework that integrates an Asymmetric Convolutional Network (AC-Net) with a multi-head attention mechanism (MHA), leveraging Transfer Learning (TL) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to generate fault data, while utilizing Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) for time-frequency representation. This method enables high-accuracy fault diagnosis of rolling bearings under multiple operating conditions, even with limited sample data from the target domain. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

(1) The integrated approach presents a hybrid method combining generative adversarial networks (GANs), transfer learning (TL), wavelet transform time-frequency representation (VWT), asymmetric convolutional network (AC-Net), and multi-head attention mechanism (MHA), abbreviated as GAN-VWT-TL-ACN-MHA. (2)To achieve accurate small-sample fault classification and detection, the integrated approach includes a fault classification method based on GANs. (3) The Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) is applied to convert bearing vibration signals into time-frequency representations, capturing the temporal evolution of frequency components and performing threshold-based denoising. (4) Building on fault detection in the source domain, transfer learning is employed to recognize bearing faults under different operating conditions, using only 10% of the target domain data for fine-tuning. This approach enables effective fault diagnosis across varying operating conditions, an area that has been underexplored in previous works. The fault detection results of the proposed MAC-MHA model on the PADERBORN and CWRU datasets are shown in Figs. 7 and 13. Furthermore, the bearing fault classification results for both datasets using CWT-MACN-MHA are presented in Figs. 9and 15. Finally, the fault recognition results across different operating conditions for both datasets are shown in Figs. 17 and 11. These results demonstrate that the proposed integrated approach effectively captures the commonalities between bearing fault detection, classification, and recognition tasks, thereby enabling intelligent bearing fault diagnosis. The computational complexity of each module is summarized as follows: the total number of parameters for the entire model during the inference phase is approximately 2.58 million, and the total FLOPS is approximately 759,557,508. Based on theoretical estimates, the model is expected to run in approximately 0.15 milliseconds on a CPU platform. Despite the overall complexity of the model, certain modules, such as the GAN, are used solely for offline data augmentation. Real-time inference primarily relies on the ACN and MHA modules, whose computational load has been optimized through asymmetric design and efficient attention mechanisms. Therefore, this approach demonstrates high feasibility for real-time fault diagnosis in industrial field applications.

Discussion

Deep learning-based fault diagnosis methods require substantial labeled data for effective training. However, obtaining such data in industrial settings is expensive and challenging69. While data augmentation techniques like GANs help address data imbalance, synthetic data may not fully capture real-world complexities, potentially reducing model generalization. Moreover, the quality of synthetic data remains a challenge, potentially introducing biases during training70. Despite deep learning models’ strong performance, their “black-box” nature hinders interpretability, which is critical in high-risk domains like fault diagnosis. The current model, incorporating convolutional layers and multi-head attention mechanisms, enhances performance but offers limited interpretability improvements. Future research could explore Explainable AI (XAI) techniques to boost transparency and model trustworthiness in industrial applications. Deep learning methods also demand significant computational resources, especially during inference. As model complexity grows, so do inference latency and computational cost, potentially limiting deployment in resource-constrained environments like edge computing71. Although GPU-based inference was used, model optimization techniques such as compression, quantization, and pruning may be needed to reduce costs and improve real-time performance in practical settings Although the current experimental results demonstrate the success of the proposed method in both theoretical and empirical validations, its performance in real-world deployment may be affected by factors such as environmental noise and equipment malfunctions, leading to fluctuations in model performance. Future research could focus on enhancing the model’s robustness by incorporating techniques such as online learning and transfer learning, enabling the model to continuously adapt to varying operational conditions and environmental changes post-deployment.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, H., Liu, Z., Alippi, C., Huang, B. & Liu, D. Explainable intelligent fault diagnosis for nonlinear dynamic systems: From unsupervised to supervised learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 35, 6166–6179. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3201511.

Liu, D., Xue, S., Zhao, B., Luo, B. & Wei, Q. Adaptive dynamic programming for control: A survey and recent advances. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybernet. Syst. 51, 142–160. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.2020.3042876.

Rezazadeh, N., Perfetto, D., de Oliveira, M., Luca, A. D. & Lamanna, G. A fine-tuning deep learning framework to palliate data distribution shift effects in rotary machine fault detection. Struct. Health Monit. https://doi.org/10.1177/14759217241295951.

Chen, H., Jiang, B., Ding, S. X. & Huang, B. Data-driven fault diagnosis for traction systems in high-speed trains: A survey, challenges, and perspectives. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 1700–1716. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2020.3029946.

Chen, H. & Jiang, B. A review of fault detection and diagnosis for the traction system in high-speed trains. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 21, 450–465. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2019.2897583.

Alippi, C., Boracchi, G. & Roveri, M. Hierarchical change-detection tests. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 28, 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2015.2512714.

Jiang, Y., Yin, S. & Kaynak, O. Performance supervised plant-wide process monitoring in industry 4.0: A roadmap. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2, 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1109/OJIES.2020.3046044.

Monopoli, V. G. et al. Applications and modulation methods for modular converters enabling unequal cell power sharing: Carrier variable-angle phase-displacement modulation methods. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 16, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIE.2021.3080232.

Chen, L. et al. Generative adversarial synthetic neighbors-based unsupervised anomaly detection. Sci. Rep. 15, 16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84863-6.

Liu, X.-M., Zhang, R.-M., Li, J.-P., Xu, Y.-F. & Li, K. A motor bearing fault diagnosis model based on multi-adversarial domain adaptation. Sci. Rep. 14, 29078. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80743-1.

Mao, M. et al. Application of FCEEMD-TSMFDE and adaptive CatBoost in fault diagnosis of complex variable condition bearings. Sci. Rep. 14, 30448. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78845-x.

Zhao, J. et al. Research on an intelligent diagnosis method of mechanical faults for small sample data sets. Sci. Rep. 12, 21996. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26316-6.

Wang, X. et al. Fault diagnosis method of rolling bearing based on SSA-VMD and RCMDE. Sci. Rep. 14, 30637. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81262-9.

Xiong, J., Cui, S. & Tang, H. A novel intelligent bearing fault diagnosis method based on signal process and multi-kernel joint distribution adaptation. Sci. Rep. 13, 4535. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31648-y.

Xiao, Q., Yang, M., Yan, J. & Shi, W. Feature decoupling integrated domain generalization network for bearing fault diagnosis under unknown operating conditions. Sci. Rep. 14, 30848. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81489-6.

Xing, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, Q. & Fu, J. Fault diagnosis of rotating parts integrating transfer learning and ConvNeXt model. Sci. Rep. 15, 190. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84783-5.

Siddique, M. F. et al. Advanced bearing-fault diagnosis and classification using Mel-Scalograms and FOX-optimized ANN. Sensors 24, 7303. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24227303 (2024).

Ullah, N., Umar, M., Kim, J.-Y. & Kim, J.-M. Enhanced fault diagnosis in milling machines using CWT image augmentation and ant colony optimized AlexNet. Sensors 24, 7466. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24237466 (2024).

Ruan, D., Wang, J., Yan, J. & Gühmann, C. CNN parameter design based on fault signal analysis and its application in bearing fault diagnosis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 55, 101877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2023.101877.

Xu, Y. et al. Cross-modal fusion convolutional neural networks with online soft-label training strategy for mechanical fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 20, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2023.3256400.

Gao, Y., Liu, X. & Xiang, J. FEM Simulation-Based Generative Adversarial Networks to Detect Bearing Faults. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 16, 4961–4971. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2020.2968370.

Liu, H. et al. Unsupervised fault diagnosis of rolling bearings using a deep neural network based on generative adversarial networks. Neurocomputing 315, 412–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2018.07.034.

Wu, B. et al. Tencent ML-images: A large-scale multi-label image database for visual representation learning. IEEE Access 7, 172683–172693. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2956775.

Grattarola, D., Zambon, D., Livi, L. & Alippi, C. Change detection in graph streams by learning graph embeddings on constant-curvature manifolds. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 31, 1856–1869. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2019.2927301.

Song, B. et al. An optimized CNN-BiLSTM network for bearing fault diagnosis under multiple working conditions with limited training samples. Neurocomputing 574, 127284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2024.127284 (2024).

Dong, Z., Zhao, D. & Cui, L. An intelligent bearing fault diagnosis framework: One-dimensional improved self-attention-enhanced CNN and empirical wavelet transform. Nonlinear Dyn. 112, 6439–6459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-024-09389-y (2024).

Ruan, D., Wang, J., Yan, J. & Gühmann, C. CNN parameter design based on fault signal analysis and its application in bearing fault diagnosis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 55, 101877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2023.101877 (2023).

Jia, L., Chow, T. W. & Yuan, Y. GTFE-Net: A Gramian time frequency enhancement CNN for bearing fault diagnosis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 119, 105794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105794 (2023).

Wang, H., Liu, Z., Peng, D. & Cheng, Z. Attention-guided joint learning CNN with noise robustness for bearing fault diagnosis and vibration signal denoising. ISA Trans. 128, 470–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2021.11.028 (2022).

Wang, X., Mao, D. & Li, X. Bearing fault diagnosis based on vibro-acoustic data fusion and 1D-CNN network. Measurement 173, 108518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108518 (2021).

Chen, X., Zhang, B. & Gao, D. Bearing fault diagnosis base on multi-scale CNN and LSTM model. J. Intell. Manuf. 32, 971–987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-020-01600-2 (2021).

Zhao, B., Zhang, X., Li, H. & Yang, Z. Intelligent fault diagnosis of rolling bearings based on normalized CNN considering data imbalance and variable working conditions. Knowl.-Based Syst. 199, 105971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2020.105971 (2020).

Wang, H., Xu, J., Yan, R. & Gao, R. X. A new intelligent bearing fault diagnosis method using SDP representation and SE-CNN. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 69, 2377–2389. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2019.2956332 (2020).

Peng, D. et al. Multibranch and multiscale CNN for fault diagnosis of wheelset bearings under strong noise and variable load condition. IEEE Trans. Indust. Inf. 16, 4949–4960. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2020.2967557 (2020).

Peng, D., Liu, Z., Wang, H., Qin, Y. & Jia, L. A novel deeper one-dimensional CNN with residual learning for fault diagnosis of wheelset bearings in high-speed trains. IEEE Access 7, 10278–10293. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2888842 (2019).

Eren, L., Ince, T. & Kiranyaz, S. A generic intelligent bearing fault diagnosis system using compact adaptive 1D CNN classifier. J. Signal Process. Syst. Signal Image Video Technol. 91, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11265-018-1378-3 (2019).

Ding, X., Guo, Y., Ding, G. & Han, J. ACNet: Strengthening the Kernel skeletons for powerful CNN via asymmetric convolution blocks. 1908.03930.

Tian, C., Xu, Y., Zuo, W., Lin, C.-W. & Zhang, D. Asymmetric CNN for image superresolution. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern, Syst. 52, 3718–3730, https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.2021.3069265.

Yang, H. et al. Asymmetric 3D convolutional neural networks for action recognition. Pattern Recognit. 85, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2018.07.028.

Li, X. et al. Bearing fault diagnosis method based on attention mechanism and multilayer fusion network. ISA Trans. 128, 550–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2021.11.020.

Liu, J., Zhang, C. & Jiang, X. Imbalanced fault diagnosis of rolling bearing using improved MsR-GAN and feature enhancement-driven CapsNet. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 168, 108664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2021.108664.

Zhou, F., Yang, S., Fujita, H., Chen, D. & Wen, C. Deep learning fault diagnosis method based on global optimization GAN for unbalanced data. Knowl. Based Syst. 187, 104837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2019.07.008.

Mao, W., Liu, Y., Ding, L. & Li, Y. Imbalanced fault diagnosis of rolling bearing based on generative adversarial network: A comparative study. IEEE Access 7, 9515–9530. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2890693 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. A systematic survey of regularization and normalization in GANs. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1145/3569928 (2020).

Tran, N.-T., Tran, V.-H., Nguyen, N.-B., Nguyen, T.-K. & Cheung, N.-M. On data augmentation for GAN training. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 30, 1882–1897. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2021.3049346 (2020).

Wang, D., Qin, X., Song, F. & Cheng, L. Stabilizing training of generative adversarial nets via Langevin Stein variational gradient descent. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 33, 2768–2780. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2020.3045082 (2020).

Cao, J., Luo, M., Yu, J., Yang, M. & He, R. ScoreMix: A scalable augmentation strategy for training GANs with limited data. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 8920–8935. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3231649 (2022).

Ren, Z., Zhu, Y., Liu, Z. & Feng, K. Few-shot GAN: Improving the performance of intelligent fault diagnosis in severe data imbalance. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2023.3271746 (2023).

Wu, Z., Jiang, H., Zhao, K. & Li, X. An adaptive deep transfer learning method for bearing fault diagnosis. Measurement 151, 107227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2019.107227.

Huang, M., Yin, J., Yan, S. & Xue, P. A fault diagnosis method of bearings based on deep transfer learning. Simul. Modell. Practice Theory 122, 102659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simpat.2022.102659.

Chen, X. et al. Deep transfer learning for bearing fault diagnosis: A systematic review since. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2023.3244237 (2016).

Zou, Y., Liu, Y., Deng, J., Jiang, Y. & Zhang, W. A novel transfer learning method for bearing fault diagnosis under different working conditions. Measurement 171, 108767, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108767.

Zhu, J., Chen, N. & Shen, C. A new deep transfer learning method for bearing fault diagnosis under different working conditions. IEEE Sensors J. 20, 8394–8402, https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2019.2936932.

Yang, J., Liu, J., Xie, J., Wang, C. & Ding, T. Conditional GAN and 2-D CNN for bearing fault diagnosis with small samples. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 70, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2021.3119135.

Ganin, Y. et al. Domain-adversarial training of neural networks. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1505.07818 (2016).

Long, M., Zhu, H., Wang, J. & Jordan, M. I. Deep transfer learning with joint adaptation networks. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1605.06636 (2017).

Long, M., Cao, Y., Wang, J. & Jordan, M. I. Learning transferable features with deep adaptation networks. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1502.02791 (2015).

Yosinski, J., Clune, J., Bengio, Y. & Lipson, H. How transferable are features in deep neural networks? https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1411.1792 (2014).

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 63, 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1145/3422622 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Deep transfer learning for bearing fault diagnosis: A systematic review since 2016. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2023.3244237 (2023).

Shao, L., Zhu, F. & Li, X. Transfer learning for visual categorization: A survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 26, 1019–1034. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2014.2330900 (2015).

Cheng, Y., Lin, M., Wu, J., Zhu, H. & Shao, X. Intelligent fault diagnosis of rotating machinery based on continuous wavelet transform-local binary convolutional neural network. Knowl. Based Syst. 216, 106796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2021.106796.

Wen, L., Li, X., Gao, L. & Zhang, Y. A new convolutional neural network-based data-driven fault diagnosis method. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 65, 5990–5998. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2017.2774777 (2018).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762 (2023).

Lessmeier, C., Kimotho, J. K., Zimmer, D. & Sextro, W. Condition monitoring of bearing damage in electromechanical drive systems by using motor current signals of electric motors: A benchmark data set for data-driven classification. PHM Soc. Eur. Conf. 3, https://doi.org/10.36001/phme.2016.v3i1.1577.

Khare, S. K. & Bajaj, V. Time–frequency representation and convolutional neural network-based emotion recognition. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 32, 2901–2909. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2020.3008938.

Hong, H., Cui, X. & Qiao, D. Simulating nonstationary non-Gaussian vector process based on continuous wavelet transform. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 165, 108340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2021.108340.

Kankar, P., Sharma, S. C. & Harsha, S. Rolling element bearing fault diagnosis using wavelet transform. Neurocomputing 74, 1638–1645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2011.01.021.

Zhang, T. et al. Intelligent fault diagnosis of machines with small & imbalanced data: A state-of-the-art review and possible extensions. ISA Trans. 119, 152–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2021.02.042 (2022).

Shao, S., Wang, P. & Yan, R. Generative adversarial networks for data augmentation in machine fault diagnosis. Comput. Ind. 106, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2019.01.001 (2019).

An, K. et al. Edge solution for real-time motor fault diagnosis based on efficient convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2023.3276513 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Benjie Zhang wrote the main manuscript text.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., Wang, W. & He, Y. A hybrid approach combining deep learning and signal processing for bearing fault diagnosis under imbalanced samples and multiple operating conditions. Sci Rep 15, 13606 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98138-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98138-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A novel diagnosis methodology of gear oil for wind turbine combining Stepwise multivariate regression and clustered federated learning framework

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Deep learning-based structural health monitoring of an ASCE benchmark building using simulated data

Asian Journal of Civil Engineering (2025)