Abstract

Neuraxial anesthesia provides effective anesthesia and analgesia for surgery, but may cause neurological complications. The rate of neurological complications in China remains unclear. This study conducted a retrospective epidemiological investigation of neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia in Guangxi, southwest China. This survey used the “Golden Data” platform to distribute questionnaires to anesthesiology departments across hospitals of varying levels in Guangxi, gathering data on neuraxial anesthesia methods and associated neurological complications from 2013 to 2022. Detailed patient information was recorded, with missing data supplemented by phone. The Adverse Event Reporting System was also utilized to verify and supplement cases, supported by peer review. The study analyzed the incidence and clinical characteristics of neurological complications after neuraxial anesthesia. A comprehensive survey was conducted across 243 hospitals, encompassing 2,723,615 cases of neuraxial anesthesia. The survey identified 1208 cases of neurological complications, with an incidence of 0.44‰, primarily occurring in patients undergoing obstetrics, gynecology, orthopedics, urology, and general surgery. The complications included transient nerve syndrome (999 cases), spinal injury (188 cases), cauda equina syndrome (13 cases), spinal hematoma (5 cases), anterior spinal artery syndrome (2 cases), and conus medullaris injury (1 case). The incidence of neurological complications associated with combined spinal-epidural anesthesia (0.53‰) was significantly higher than that of epidural anesthesia (0.21‰) and spinal anesthesia (0.35‰) (P < 0.001). Among the patients, 97.3% achieved full recovery, while 2.7% (30 cases) suffered permanent neurological damage. Although neurological complications are relatively rare, comprehensive preoperative assessment, adherence to standardized protocols, and vigilance regarding potential complications are essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuraxial anesthesia remains an important method in anesthesia practice due to its numerous advantages, including minimal equipment requirement, simplicity of drug administration, lower cardiovascular effects, expedited postoperative recovery, and applications in perioperative medicine for both postoperative analgesia and labor analgesia1,2,3,4,5. This technique is particularly prevalent in grassroots hospitals where access to general anesthesia may be limited. However, it is important to note that neurological complications can occur, potentially arising from spinal injury during the procedure or neurotoxicity of local anesthetics6,7,8,9. Numerous cases of neurological complication following neuraxial anesthesia have been reported10,11,12,13,14.

Currently, the majority of large retrospective or observational studies on the incidence of complications associated with neuraxial anesthesia are derived from closed malpractice claims, postal surveys, and literature reviews15,16,17,18,19. Furthermore, there is a paucity of studies that specifically address neurological complications resulting from neuraxial anesthesia. The study conducted by Brull et al. serves as a review of 32 studies involving neurological complications subsequent to neuraxial anesthesia and peripheral nerve blocks, revealing an incidence rate of neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia of 0.4‰ in 200717. A retrospective survey conducted in Japan examined neurological complications associated with neuraxial anesthesia, reporting an incidence of spinal cord injury of 0.013‰ among 548,819 cases of neuraxial anesthesia in 200720. In another study, the incidence of severe neurological complications following central neuraxial blockades in Sweden was 0.074‰ among 1,710,000 blockades in 200418. However, the incidence of neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia in China remains unclear.

The primary categories of neurological complications include transient neurological syndrome (TNS), cauda equina syndrome (CES), spinal nerve root injury, anterior or posterior spinal artery syndrome, and neurological manifestations attributable to spinal hematoma or infection21. The extent of recovery is contingent upon the specific type of complication: patients with TNS generally attain full recovery, whereas other complications may result in enduring nerve damage. Such outcomes impose considerable psychological and economic burdens on patients, and may precipitate medical disputes. Therefore, it is imperative to critically collect and scrutinize data regarding neurological complications associated with neuraxial anesthesia. This study aimed to perform a retrospective epidemiologic investigation on the incidence and outcomes of neurological complications across 243 hospitals in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China, from 2013 to 2022.

Materials and methods

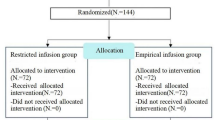

Survey

The survey, comprising a Microsoft Excel table and questionnaire, was disseminated via the “Golden Data” network platform to the heads of departments and clinical anesthesia quality controllers across all primary, secondary and tertiary hospitals of anesthesia departments in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of China. This retrospective investigation received approval from the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Approval No.: 2022-K064-01) and was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (www.chictr.org.cn) under registration number ChiCTR2200065239 on November 1, 2022. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. For all patients with neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia that were surveyed, we obtained written informed consent from the patients or their guardians via phone.

The study recipients were instructed to document cases involving all anesthesia methods employed within their departments from 2013 to 2022, including epidural anesthesia (EA), combined spinal-epidural anesthesia (CSEA), spinal anesthesia (SA), general anesthesia (GA), peripheral nerve block (PNB), and other anesthesia techniques on the provided Excel sheet, as well as the number of neurological complications associated with neuraxial anesthesia. For departments documenting neurological complications, recipients were mandated to complete an additional questionnaire. The purpose of this questionnaire was to correlate each previously reported complication with specific patients. The data collected included the patient’s sex, age, surgical department, type of anesthesia administered, history of neuraxial anesthesia, use of postoperative epidural analgesia pumps, number of spinal or epidural punctures, local anesthetic concentration and dosage, any special events occurring during anesthesia, radiographic evaluations (including lumbar MRI or CT), and treatment and recovery outcomes with first year post-surgery. Questionnaires with incomplete information were obtained via telephone consultations. The risk of bias was not evaluated, because the study exclusively involved patients with neurological complications and only comprised clinical data and consequences.

Adverse event reporting system

Parallel to the online investigation, adverse event reports pertaining to neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia were examined using the direct reporting system of the medical adverse event network within the Guangxi Anesthesiology Department. To enhance the quality of clinical anesthesia in Guangxi, all departments, especially quality control specialists, are obligated to report anesthesia-related adverse events using this online system. Subsequently, all reported cases underwent peer review. We reviewed and scrutinized all instances of neurological complications associated with neuraxial anesthesia.

Definitions

EA was defined as the insertion of an epidural catheter into the vertebral space via an epidural puncture needle, followed by the administration of a local anesthetic through the catheter. SA entails the injection of a local anesthetic using a thin spinal needle, which may be performed independently or facilitated by an epidural needle. Moreover, once spinal anesthesia was successfully administered during neuraxial anesthesia, the insertion of an epidural catheter, irrespective of whether the local anesthetic was administered intraoperatively or solely for postoperative epidural analgesia, was classified as CESA. Additionally, CESA was defined in cases where it was initially planned, but due to the absence of cerebrospinal fluid return from the spinal anesthesia needle, the decision was made to forgo subarachnoid anesthesia and proceed with the placement of an epidural catheter for the administration of EA.

Intravertebral hematomas can be situated within epidural or subdural spaces. In this study, all instances of intravertebral hematomas were referred to as “spinal hematomas”. This study exclusively considered cases of CES attributed to local anesthetic, either due to its toxic effects or presumed compression resulting from the volume effect of the local anesthetic. Patients with CES caused by spinal hematoma or epidural abscess were excluded from the CES group.

TNS was defined as the clinical evaluation and neurological examination of patients conducted by anesthesiologists. In cases of suspected or confirmed complications of other types, a neurological examination of the lower extremities by a neurologist within 24 h was mandated to collaboratively determine the diagnosis and treatment measures. Consequently, patients exhibiting confirmed or suspected neurological symptoms were included in the study on neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia. Patients with pre-existing neurological symptoms or neuropathy prior to surgery were excluded from the study.

Spinal cord injuries can vary in severity, ranging from mild to severe. The clinical manifestations of mild spinal cord injury and spinal nerve root injury exhibit considerable overlap, often presenting as unilateral or bilateral paresthesia or numbness in the lower extremities or localized areas following neuraxial anesthesia, with or without accompanying muscle strength impairment. Consequently, distinguishing the specific type of neurological complication based solely on clinical symptoms and ancillary examinations may be challenging. For the purposes of this article, both spinal cord injury and spinal nerve root injury are collectively referred to as “spinal injury”. Permanent neurological injury was defined as symptoms persisting for more than one year.

Results

Number of anesthesia cases

Utilizing the survey compiled in Microsoft Excel, we gathered 9,555,023 cases of anesthesia in operating rooms across 243 hospitals from 2013 to 2022. Among these cases, neuraxial anesthesia accounted for 2,459,805 instances, representing 25.74% of the total, thereby constituting the largest proportion of anesthesia methods followed by general anesthesia.

Neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia

China initiated the promotion of labor analgesia in November 2018, prompting the commencement of data collection on labor analgesia cases from 2019 onwards. Between 2019 and 2022, a cumulative total of 263,810 instances of neuraxial analgesia for labor analgesia were recorded in Guangxi. Specifically, the annual figures are as follows: 75,643 cases in 2019, 70,527 cases in 2020, 53,671 cases in 2021, and 63,969 cases in 2022. The data on neurological complications encompassed labor analgesia following neuraxial anesthesia, resulting in an overall total of 2,723,615 neuraxial anesthesia cases.

The types of neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia were TNS, spinal injury, CES, spinal hematoma, anterior spinal artery syndrome and conus spinal injury in this study. Neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia were documented across 162 hospitals, resulting in a total of 1144 cases, as indicated in the Microsoft Excel dataset. An additional 64 cases were identified solely through the direct reporting system for adverse events, which included 44 instances of TNS, 15 cases of spinal injury, three occurrences of CES, and two instances of spinal hematoma. All cases retrieved from the direct reporting system were analyzed by members of the quality control team, who determined that these complications were attributable to neuraxial anesthesia. Detailed clinical case records were obtained for each instance. The total number of neurological complications was 1208 (see Table 1). In addition to these neurological complications, several other complications associated with neuraxial anesthesia have been reported in the adverse event reporting system. These included residual epidural catheter fracture, high spinal anesthesia, total spinal anesthesia, excessively wide epidural block levels, headache following epidural rupture, and central toxicity of local anesthetics. However, they were excluded from the analysis because they were not classified as neurological complications.

Among the various types of neurological complications, TNS constituted the majority (82.7%), followed by spinal injury (15.5%), CES (1.1%), and a combined incidence of 0.7% for spinal hematoma, anterior spinal artery syndrome, and conus medullaris injury (see Table 1).

Between 2013 and 2022, a total of 2,723,615 cases of neuraxial anesthesia were recorded, along with 1208 instances of associated neurological complications, resulting in a neurological complication incidence rate of 0.444‰. Notably, 818 (67.7%) of these complications occurred between 2013 and 2017. The incidence of complications has exhibited a downward trend from 2013 to 2022. A greater incidence of neurological complications was observed following CSEA, with a rate of 0.53‰, which was significantly higher than the rates associated with EA at 0.21‰ and SA at 0.35‰ over the 10-year survey period. Furthermore, the incidence of neurological complications following SA was higher than that associated with EA (see Table 2).

Neurological complications in different anesthesia methods and surgical types

Among the three types of neuraxial anesthesia, neurological complications following CSEA constituted the majority, accounting for 83.6% of cases. Notably, of the 13 cases of CES, 12 cases were associated with CSEA (see Table 3).

Given that gynecology and obstetrics are often housed within the same departmental framework in numerous hospitals, this study analyzed them collectively. Notably, neurological complications predominantly occurred in obstetric and gynecological populations, constituting 60.7% of all complications. This was followed by orthopedic surgery at 20.0%, general surgery at 10.4%, and urological surgery at 8.9% (see Table 3).

Clinical information of patients with neurological complications

Table 4 presents a summary of clinical data of the 1,208 patients who experienced neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia. Notably, the proportion of female patients exceeded that of male patients, which may be attributed to the greater number of obstetric and gynecological surgeries than general surgery or orthopedic procedures. Additionally, 253 patients (20.9%) had a documented history of neuraxial anesthesia.

In the recorded for the number of neuraxial punctures, 710 cases (82.5%) were successful on the first attempt, while 57 cases (6.6%) necessitated three or more “in and out” needle passes during the procedure. The primary reasons for multiple punctures included unclear puncture sites, catheter dislodgment, patient non-compliance, and requirement for re-puncture due to patients experiencing an abnormal sensation during the procedure. Among the 1208 cases of neurological complications, 347 cases lacked documentation regarding the number of epidural or lumbar needle punctures and 289 cases did not record abnormal sensory information. In total, 197 patients (21.4%) reported experiencing abnormal sensations during the puncture process.

Among patients who underwent SA and CESA, 945 (89.6%) underwent puncture at the L3-L4 interspace, whereas 110 (10.4%) went puncture at the L1-L2 interspace. After surgery, 566 patients (48.8%) used an epidural patient-controlled analgesia pump for 2–3 days; data on analgesia pump usage were not recorded for 48 cases.

Of the 1208 patients with neurological complications, only 393 had available lumbar CT or MRI data. Among these, the imaging results of 104 patients revealed no significant abnormalities. Moreover, 289 patients exhibited various pathological findings, including disc herniation (degeneration, protrusion, posterior protrusion) at different lumbar segments, interspinous ligament edema, Schmorl’s node formation at vertebral edges, nerve root compression, bilateral lateral recess narrowing, and lumbar vertebrae osteophytes.

Recovery of neurological complications

Of the 1144 questionnaires received, 75 patients with TNS and 19 patients with spinal injury were recorded only numerically and anesthesia methods, without specific information and patient outcomes. One patient with CES had severe symptoms and was transferred to a superior hospital for treatment, which was considered incomplete recovery and permanent neurological injury. All 64 complications were reported in detail using the adverse event recording system. Therefore, a total of 1114 patients with neurological complications had specific information, 1050 from the questionnaires and 64 from the direct reporting system of adverse event. The overall recovery rate for neurological complications was 97.3%, with 30 cases resulting in permanent neurological injury (see Table 5).

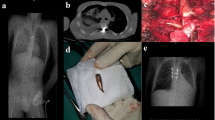

Permanent nerve injury could be minor or major. Among the patients with spinal injury, 155 (91.7%) achieved full recovery, while 14 experienced permanent neurological damage, with detailed clinical information available in Table 6. Of these 14 cases, 12 involved minor injury and two were major injury. Details information regarding patients with other serious neurological complications, such as CES, epidural hematoma, anterior spinal artery syndrome, and conus spinal injury, is provided in Table 7.

Discussion

Our study was conducted over a ten-year period in the Guangxi, encompassing 2,723,615 cases of neuraxial anesthesia across 243 hospitals. This represents the only investigation into neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia conducted within a provincial region in China. Our results indicated that the overall incidence of neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia was 0.44‰, aligning with the findings reported by Brull and others17. The incidence of severe neurological complications, including spinal injury, CES, spinal hematoma, anterior spinal artery syndrome, and conus medullaris injury, was found to be 0.077‰, consistent with the results of Moen and Irestedt18. The incidence of permanent neurological complications was 0.011‰. Despite the extremely low incidence of neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia and the fact that most patients achieved complete recovery post-treatment, a subset of patients experienced permanent neurological damage. This outcome has significant ramifications for affected patients, their families, and attending anesthesiologists.

This survey indicated a progressive reduction in the incidence of neurological complications associated with neuraxial anesthesia in Guangxi over the decade spanning from 2013 to 2022. This decline may be attributed to several factors, including heightened awareness of neurological complications among anesthesiologists in Guangxi, the implementation of epidural wire catheters, enhancements in the types of local anesthetics utilized, and advancements in the techniques of epidural and spinal anesthesia22,23,24. Based on the survey results, it can be concluded that the incidence of neurological injury complications associated with EA was the lowest, suggesting that neuraxial anesthesia should prioritize the use of EA. Among patients undergoing SA and CSEA, 10.4% (110 out of 1,055 patients) had puncture points located at the L2-L3 intervertebral space. Existing literature indicates that anesthesiologists demonstrate an accuracy of only 29% in anatomically identifying intervertebral spaces25, which frequently exceeds the actual puncture site. This discrepancy may contribute to the higher incidence of neurological complications observed following SA and CSEA than following EA. Studies have demonstrated that intrathecal administration of ropivacaine exhibited the lowest neurotoxicity when compared to intrathecal injections of levobupivacaine, bupivacaine, procaine, and lidocaine26,27. Consequently, ropivacaine is recommended as the preferred local anesthetic for intrathecal injection in Guangxi.

A prospective study identified multiple attempts at epidural placement, paresthesia during insertion, history of neuraxial anesthesia, and use of patient-controlled epidural analgesia as risk factors for neurologic complications28. Within the surveyed population, 6.6% of the patients with neurological complications experienced three or more attempts at neuraxial needle insertion. The success rate of single punctures in neuraxial anesthesia was 82.5%. However, the records of puncture attempts for 347 patients were absent, which may have contributed to a decreased likelihood of successful single punctures being documented. Therefore, for patients in unique clinical scenarios, such as those with edema or at an elevated risk of neurological complications due to challenging puncture sites, it is recommended to utilize ultrasound guidance whenever feasible29. Additionally, SA or CSEA should ideally be administered at the L3-L4 interspace.

Among the 1160 patients experiencing neurological complications, 48.8% utilized patient-controlled epidural analgesia. The existing literature indicates that the continuous administration of local anesthetics into the nerve or nerve bundles, particularly following the misplacement of the epidural catheter into the intervertebral foramen, can result in altered nerve function and blockade30; therefore, if patients exhibit nerve root stimulation during the puncture process, it is not recommended to use an epidural analgesia pump, and the depth of the epidural catheter should be limited to less than 6 cm31. Additionally, if patients experience sensations akin to electric shocks during the puncture process, the procedure should be halted, or the interspace should be adjusted.

Imaging findings of patients with neurological complications revealed varying degrees of lumbar disc herniation or spinal canal stenosis in this investigation. A study utilizing MRI examination showed anatomical abnormalities of the spinal canal in individuals with lumbar disc herniation, which may contribute to neurologic deficits resulting from neuraxial blockade32. Furthermore, patients presenting with preoperative lumbar nerve lesions have an elevated risk of postoperative neurological damage33,34,35. Consequently, patients with pre-existing central nervous system disorders (including multiple sclerosis, post-polio syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, spinal stenosis, and disc diseases), inflammatory diseases (such as Guillain-Barré syndrome and postoperative inflammatory changes), and peripheral nervous system diseases (both hereditary and acquired, such as diabetic polyneuropathy and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy) should meticulously evaluate the advantages and disadvantages before opting for neuraxial anesthesia.

Therefore, neuraxial anesthesia must encompass a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s clinical status and adherence to standardized procedures to minimize the incidence of neurological complications. Meticulous post-anesthetic monitoring is essential to facilitate the identification of potential mismanagement and to mitigate the risk of neurologic injury, thereby enhancing overall patient outcomes. Additionally, this study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, being a retrospective analysis, the data were sourced from historical medical records, which may suffer from incomplete documentation or the absence of crucial variables, thereby potentially compromising the accuracy of the findings. Secondly, the 10-year duration of the study may encompass significant advancements in medical technologies, shifts in diagnostic criteria, and changes in data recording practices, thereby introducing temporal heterogeneity that could affect the consistency and comparability of the data. Despite efforts to conduct the investigation as thoroughly as possible, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Despite the relatively low incidence of neurological complications associated with neuraxial anesthesia, the potential severity of these complications warrants significant clinical attention. In the context of perioperative management, it is imperative for healthcare professionals to maintain heightened vigilance in preventing and promptly detecting neurological complications.

Data availability

The data used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Watson, S. E., Richardson, A. L. & Lucas, D. N. Neuraxial and general anaesthesia for caesarean section. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 36, 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2022.04.007 (2022).

Amoroso, K., Hughes, A. P. & Soffin, E. M. Spine surgery under neuraxial vs. general anesthesia: the current state of comparative outcomes research. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 36, 516–524. https://doi.org/10.1097/aco.0000000000001294 (2023).

Amoroso, K. et al. Comparative effectiveness of anesthetic technique on outcomes after lumbar spine surgery: a retrospective propensity score-matched analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, 2009–2019. Reg. Anesth. Pain. Med. 48, 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2022-104098 (2023).

Halliday, L., Nelson, S. M. & Kearns, R. J. Epidural analgesia in labor: A narrative review. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 159, 356–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14175 (2022).

Karsten, M. B., Staffa, S. J., McClain, C. D., Amon, J. & Stone, S. S. D. Epidural analgesia for reduction of postoperative systemic opioid use following selective dorsal rhizotomy in children. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 27, 594–599. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.9.Peds20501 (2021).

Cook, T. M., Counsell, D. & Wildsmith, J. A. Major complications of central neuraxial block: Report on the Third National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Br. J. Anaesth. 102, 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aen360 (2009).

Shams, D., Sachse, K., Statzer, N. & Gupta, R. K. Regional anesthesia complications and contraindications. Anesthesiol. Clin. 42, 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anclin.2023.11.013 (2024).

Pozza, D. H., Tavares, I., Cruz, C. D. & Fonseca, S. Spinal cord injury and complications related to neuraxial anaesthesia procedures: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054665 (2023).

Cai, X. Y. et al. Comparison of toxicity effects of ropivacaine, bupivacaine, and lidocaine on rabbit intervertebral disc cells in vitro. Spine J. 14, 483–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.041 (2014).

Marinho, S. et al. Cauda equina syndrome following combined spinal-epidural anesthesia with levobupivacaine for cesarean section. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim (Engl. Ed.) 68, 484–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redare.2020.08.012 (2021).

Shimauchi, T., Yoshino, J. & Fujimura, N. A case of spinal nerve neurotoxicity with ropivacaine after combined spinal and epidural anesthesia. JA Clin. Rep. 7, 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40981-021-00476-2 (2021).

Bhosle, R. et al. Spinal subdural hematoma following epidural anesthesia. Asian J. Neurosurg. 18, 347–351. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1768576 (2023).

Seidel, R., Tietke, M., Heese, O. & Walter, U. Serious complications after epidural catheter placement: Two case reports. Local Reg. Anesth. 14, 117–124. https://doi.org/10.2147/lra.S324362 (2021).

Kulkarni, S. S. et al. Major complications following central neuraxial block - A multi-centre observational study in Maharashtra (MGMM CNB Study). Indian J. Anaesth. 67, S15-s28. https://doi.org/10.4103/ija.ija_747_22 (2023).

Huang, H. et al. A contemporary medicolegal claims analysis of injuries related to neuraxial anesthesia between 2007 and 2016. J. Clin. Anesth. 57, 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2019.03.013 (2019).

Pitkänen, M. T., Aromaa, U., Cozanitis, D. A. & Förster, J. G. Serious complications associated with spinal and epidural anaesthesia in Finland from 2000 to 2009. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 57, 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12064 (2013).

Brull, R., McCartney, C. J., Chan, V. W. & El-Beheiry, H. Neurological complications after regional anesthesia: Contemporary estimates of risk. Anesth. Analg. 104, 965–974. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000258740.17193.ec (2007).

Moen, V., Dahlgren, N. & Irestedt, L. Severe neurological complication after central neoraxial blockades in Sweden 19901999. Anesthesiology 101, 950–959. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200410000-00021 (2004).

Samara, E., Tzoumas, L., Tzoumas, K., Tzimas, P. & Papadopoulos, G. Serious complications related to regional anaesthesia: Study of Greek Courts’ Decisions. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 55, 109–113. https://doi.org/10.5114/ait.2023.129302 (2023).

Irita, K. et al. Survey of nerve injury associated with epidural/spinal anesthesia in Japan which occurred in the year 2004. Masui 56, 469–480 (2007).

Shams, D., Sachse, K., Statzer, N. & Gupta, R. K. Regional anesthesia complications and contraindications. Clin. Sports Med. 41, 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2021.11.006 (2022).

Breivik, H. et al. Reducing risk of spinal haematoma from spinal and epidural pain procedures. Scand J. Pain 18, 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2018-0041 (2018).

Doelakeh, E. S. & Chandak, A. Risk factors in administering spinal anesthesia: A comprehensive review. Cureus 15, e49886. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.49886 (2023).

Vadhanan, P. Recent updates in spinal anesthesia-A narrative review. Asian J. Anesthesiol. 59, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.6859/aja.202106_59(2).0001 (2021).

Broadbent, C. R. et al. Ability of anaesthetists to identify a marked lumbar interspace. Anaesthesia 55, 1122–1126. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01547-4.x (2000).

Hampl, K., Steinfeldt, T. & Wulf, H. Spinal anesthesia revisited: Toxicity of new and old drugs and compounds. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 27, 549–555. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000108 (2014).

Takenami, T. et al. Intrathecally administered ropivacaine is less neurotoxic than procaine, bupivacaine, and levobupivacaine in a rat spinal model. Can. J. Anaesth. 59, 456–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-012-9685-9 (2012).

Kang, X. H. et al. Major complications of epidural anesthesia: A prospective study of 5083 cases at a single hospital. Acta. Anaesthesiol. Scand. 58, 858–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12360 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Comparison of ultrasound-guided and traditional localisation in intraspinal anesthesia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open 13, e071253. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-071253 (2023).

Kapur, E. et al. Neurologic and histologic outcome after intraneural injections of lidocaine in canine sciatic nerves. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 51, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01169.x (2007).

Mhyre, J. M., Greenfield, M. L., Tsen, L. C. & Polley, L. S. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials that evaluate strategies to avoid epidural vein cannulation during obstetric epidural catheter placement. Anesth. Analg. 108, 1232–1242. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e318198f85e (2009).

Kaydu, A., Andan, İ, Deniz, M. A., Bilge, H. & Başol, Ö. Examination of spinal canal anatomy with MRI measurements in lomber disc herniation patients: An anesthesiologist viewpoint. Anesth. Essays Res. 15, 38–44. https://doi.org/10.4103/aer.aer_64_21 (2021).

Finucane, B. T. & Terblanche, O. C. Prolonged duration of anesthesia in a patient with multiple sclerosis following paravertebral block. Can. J. Anaesth. 52, 493–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03016529 (2005).

Kopp, S. L., Jacob, A. K. & Hebl, J. R. Regional anesthesia in patients with preexisting neurologic disease. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 40, 467–478. https://doi.org/10.1097/aap.0000000000000179 (2015).

Cung, S., Ritz, M. L. & Masaracchia, M. M. Regional anesthesia in pediatric patients with preexisting neurological disease. Paediatr. Anaesth. 31, 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.14152 (2021).

Funding

This article was funded by Guangxi Medical and Health Appropriate Technology Development and Promotion Application Project, (Grant No. S2021109), Guangxi Key Research and Development Program, Guike (Grant No. AB16380241).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LPS and JMJ: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft and Visualization. ZXM: Data curation and Investigation. XLX: Investigation, Data curation and Visualization. JL: Investigation and Writing-review & editing. YD: Resources and Software. SSW: Investigation and Validation. KYL: Resources and Conceptualization. YZ: Investigation. YJH: Investigation and Software. YNL: Supervision, Writing-review & editing and Project administration. JCL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-review & editing, Supervision and Project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shu, Lp., Ji, Jm., Mao, Zx. et al. Epidemiologic investigation on neurological complications following neuraxial anesthesia in 2.7 million cases in Southwest China. Sci Rep 15, 13497 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98142-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98142-5