Abstract

Sustainable vegetable production depends on the effective integration of conservation tillage practices with suitable transplanting technologies. This study analyzes the interaction between conservation and conventional tillage practices and the performance of three transplanter types: disc-type, carousel-type, and dibble-type. A split-plot experimental design was employed, where tillage methods (Conventional 1, Conservation 1, Conventional 2, and Conservation 2) were assigned to main plots, and transplanter types (disc-type, carousel-type, and dibble-type) were assigned to subplots. Key performance metrics, including seedling spacing, planting depth, gripping force, vertical positioning, damage rate, and survival rate, were evaluated for tomato and watermelon seedlings. The findings revealed consistent seedling spacing across transplanter types and tillage methods, while other performance indicators varied significantly. Under conservation tillage conditions, the dibble-type transplanter yielded suboptimal survival rates, with tomato seedling survival dropping to 75%, below the acceptable 90% threshold. In contrast, disc and carousel transplanters achieved higher survival rates under similar conditions, albeit with slightly increased damage rates, up to 8.1% for watermelon seedlings. This study highlights the necessity of selecting compatible transplanting equipment for the successful implementation of conservation tillage systems. By identifying optimal transplanter-tillage combinations, the research contributes to the advancement of sustainable vegetable production practices. Future studies should address crop-specific requirements and their interactions with conservation tillage and transplanting equipment to refine these recommendations further.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The importance of tillage practices in modern agriculture cannot be overstated, especially regarding the successful establishment of transplanted seedlings. Tillage is a crucial pre-planting operation that directly impacts soil structure, moisture retention, nutrient availability, and, ultimately, crop performance1. Its primary functions include soil aeration, weed control, and the creation of a favorable seedbed, all of which are essential for ensuring the optimal growth of seedlings.

Transplanting, the process of transferring seedlings from nurseries to the main field, is a common method for crop establishment, particularly in horticulture and vegetable production. Recent studies have critically evaluated the performance of various transplanters designed for potted seedlings, highlighting key factors that influence their efficacy during the transplantation process. Research findings suggest that operational efficiency and the mechanical handling of seedlings are paramount in ensuring high survival rates and optimal growth post-transplantation. Studies focusing on metrics such as speed, seedling damage, and overall transplant success emphasize how these performance indicators can affect agricultural productivity and seedling establishment in different environments. This body of research provides a comprehensive evaluation that can serve as a guideline for improving current transplanter designs and fostering advancements in agricultural practices, particularly in the use of potted seedlings, which are increasingly utilized in modern farming systems2,3. Successful transplanting hinges on several factors, including seedling quality, planting depth, and soil conditions, which are directly influenced by tillage practices4,5,6. In the context of transplanting, particularly for crops that rely on mechanical transplanters, the choice of tillage method becomes even more critical as it influences the efficiency of the transplanting.

The performance of different transplanter mechanisms, such as disc-type, carousel-type, and dibble-type transplanters, can vary significantly based on the tillage method used7,8. Each transplanter type—designed for specific seedling handling and placement techniques, whether in furrows or holes—interacts uniquely with the soil conditions created by various tillage practices.

The transplanter, a machine designed to automate the process of planting seedlings, is widely used in various agricultural systems to enhance labor efficiency and planting uniformity. However, the performance of a transplanter is heavily dependent on the condition of the soil, which is, in turn, determined by the tillage method employed. Proper tillage can ensure that the soil is loose and friable, facilitating the smooth operation of the transplanter, reducing transplanting stress on the seedlings, and improving their establishment. Conversely, inadequate tillage can lead to soil compaction, poor root-soil contact, and uneven planting, ultimately reducing the crop’s yield potential. The integration of tillage and transplanting mechanisms plays a vital role in improving transplanter performance and ensuring successful seedling establishment. Research has shown that transplanter design innovations, such as hopper-type planting devices and conical distributor cup mechanisms, enhance planting accuracy and seedling orientation, which are critical for growth and yield9,10. Importantly, tillage operations directly influence these performance aspects by affecting planting depth, spacing uniformity, and soil conditions. Proper tillage ensures optimal furrow formation, creating favorable conditions for transplanters to operate efficiently and improve overall agricultural productivity.

Previous research has extensively explored the effects of tillage methods on soil properties and crop performance. Conventional tillage, which typically involves the use of moldboard plows, disc harrows, and rollers, has been shown to effectively prepare the seedbed by thoroughly mixing the soil and incorporating crop residues. However, it can also lead to soil erosion, loss of organic matter, and degradation of soil structure over time. Conservation tillage methods, such as the use of chisel plows and disc harrows, aim to minimize soil disturbance and preserve soil structure and organic matter. Studies have demonstrated that conservation tillage can improve soil moisture retention, reduce erosion, and enhance soil microbial activity. However, the effectiveness of these methods may vary depending on climatic factors, soil characteristics, and the specific crop species involved.

Extensive research has been conducted on tillage practices and their effects on crop production. For instance, Pearsons et al.11, Pittarello et al.12, and Wulanningtyas et al.13 emphasized the role of conventional tillage in improving short-term crop yields by creating optimal seedbed conditions but also highlighted its detrimental effects on soil health due to increased erosion and organic matter depletion. Hobbs et al.14 compared conventional and conservation tillage methods, demonstrating that while conservation tillage offers environmental benefits such as reduced soil erosion and enhanced moisture retention, it can also present challenges in achieving the desired seedbed conditions, particularly in certain soil types and climates.

Tillage methods play an important role in agricultural research, particularly in their relationship to seeding or transplanting. Conventional tillage, characterized by deep soil inversion, has historically been the predominant method. However, its negative impacts on soil erosion, energy consumption, and environmental quality have prompted a shift towards conservation tillage methods13,15. Numerous studies have investigated how different tillage systems influence soil physical characteristics, weed control, and crop germination. Reduced tillage practices have been shown to increase soil organic matter levels, enhance water infiltration, and reduce soil erosion compared to conventional tillage methods16,17. Additionally, recent research highlights the impact of tillage systems on both soil conditions and machinery performance. Askari et al.18 examined the tractive performance of tractors during semi-deep tillage, demonstrating how tool type, depth, and speed influence slippage, drawbar power, and traction efficiency. Meanwhile, Abo-Habaga et al.19 investigated the effects of different tillage systems on soil moisture and crop productivity, emphasizing the interaction between soil properties and tillage practices. These findings reinforce the importance of selecting appropriate tillage methods for optimizing both soil health and agricultural mechanization efficiency.

Despite the wealth of knowledge on the general effects of tillage, there remains a significant gap in the academic literature regarding how different tillage methods affect the operation of transplanters and, consequently, the establishment and performance of transplanted crops. While some research has examined the effects of tillage on seedling establishment and early growth, studies comparing the performance of different transplanter models under varying tillage conditions are relatively scarce. For example, Han et al.20 noted that the efficiency of transplanters could vary significantly based on soil conditions, particularly in terms of how well the soil is prepared before transplanting. However, their study primarily focused on the mechanics of transplanters rather than the interaction between tillage methods and transplanter performance. Similarly, Morse et al.21 and Frasconi et al.22investigated the use of precision transplanters in conservation tillage systems but did not comprehensively assess how different tillage methods might influence the performance of various transplanter models. Çay and Aykas23 explored the effects of tillage methods on tomato yield and selected quality parameters in industrial tomato production. They modified a conventional transplanter and designed new rippled disc prototypes to enable effective transplanting in no-tillage conditions. Their research demonstrated that tomato yields were superior with conventional tillage practices in comparison to no-tillage approaches. However, their study primarily focused on yield and yield-related factors in no-tillage systems rather than on assessing specific transplanter performance metrics.

Research on the adaptability of transplanters to conservation tillage systems remains limited. Çay and Aykas23 and Miah et al.24 highlighted the need for more research on this aspect, noting that most existing machines are optimized for conventionally tilled soils. Additionally, the specific interactions between different tillage methods and transplanter performance have received less attention. Jiang et al.25 explored the impact of soil preparation on transplanter efficiency but limited their research to a single tillage method and transplanter type, leaving a significant gap in understanding how various tillage practices might influence the performance of different transplanter models.

Despite the extensive research on tillage practices, there remains a gap in the academic literature regarding the specific effect of different tillage methods on the performance of various transplanter models. Most studies have concentrated on the effect of tillage on soil properties and crop yields, with limited attention given to the interaction between tillage methods and transplanter performance. This gap in the academic literature emphasizes the importance of conducting further research to analyze how different tillage methods affect the efficiency and performance of transplanters, particularly in relation to seedling establishment.

This study endeavors to address existing knowledge gaps by systematically evaluating the influence of four distinct tillage methods on the performance of three transplanter models: disc-type, carousel-type, and dibble-type (Fig. 1). By systematically comparing conventional and conservation tillage methods in conjunction with these transplanter models, the research seeks to provide a comprehensive analysis of their impact on transplanting efficiency and seedling establishment. The objective is to identify the optimal combinations of tillage methods and transplanter models that yield the best results. The findings will offer valuable insights for farmers and agricultural engineers, guiding the selection of tillage and transplanting equipment to enhance crop production and sustainability.

Materials and methods

Research site and tillage techniques

The research site was established at the Aksu Farm, an agricultural research facility affiliated with Akdeniz University, located at 36.917855° N, 30.887540° E, at an altitude of approximately 46 m. The soil at this location was classified as a silty loam, characterized by a particle size distribution comprising 36% clay, 26% silt, and 38% sand. The experimental field had previously been cultivated with wheat, and the average stubble height at the time of tillage was approximately 55 mm. The soil was free of rocks and hard clay clods, ensuring uniform working conditions across all tillage methods.

The study evaluated four distinct tillage methods: Conventional 1, which followed a traditional sequence involving a moldboard plow, disc harrow, and roller; Conservation 1, employing a chisel plow, disc harrow, and roller within a conservation tillage approach; Conventional 2, utilizing a combination of a chisel plow, powered rotary tiller, and roller; and Conservation 2, which applied a disc harrow and roller.

The tillage equipment utilized in the study is commonly used in Antalya Province. In the Conventional 1 method, the plowing depth was adjusted to 240 mm, while in both the Conservation 1 and Conventional 2 methods, the chisel depth was set at 320 mm. The tillage depth of the rotary tiller and disc harrow was adjusted to 210 mm and 90 mm, respectively. Conventional 1 and Conservation 1 methods involved two passes with the disc harrow, while the Conservation 2 method required three passes. All experimental plots were subjected to two passes of rolling to enhance soil compaction, disintegrate clods, and facilitate the creation of a uniform seedbed. The details of the tillage equipment are provided in Table 1.

The Conservation 1 and Conservation 2 methods were classified as conservation tillage because they did not involve moldboard plowing, which is the primary cause of complete soil inversion and excessive soil disturbance. Unlike Conventional 2, which included a powered rotary tiller that intensively fragmented the soil, these methods relied on chisel plowing or shallow disc harrowing, which loosens the soil while preserving more surface residue, thereby aligning with the principles of conservation tillage.

Organic matter content was quantified using the standard loss on ignition technique, following the protocols established by Al-Shammary et al.26. Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were assessed using a pH meter and an EC meter in 1:1 water extracts. A cylindrical core was employed to extract samples from the top 100 mm soil layer to determine bulk density and moisture content on a dry basis (Table 2). These samples were subsequently dried and weighed, adhering to the established methodologies of Afshar et al.27and Franzluebbers28. For each treatment, measurements were conducted at six distinct locations within the soil profile. The examined soil layer exhibited organic matter content, pH, and electrical conductivity (EC) of 6.5%, 7.22, and 10.01 dS/m, respectively.

Transplanter specifications

This study compared three distinct transplanter types:

-

1.

(1) Disc-type transplanter: Engineered to efficiently position bare-root seedlings within furrows.

-

2.

(2) Carousel-type transplanter: Adaptable for transplanting both bare-root and potted seedlings into furrows.

-

3.

(3) Dibble-type transplanter: Designed to precisely place bare-root or potted seedlings into pre-formed holes.

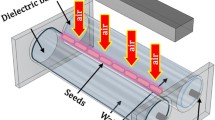

To evaluate the performance of these transplanters, tomato and watermelon seedlings were utilized. These vegetable species are commonly cultivated from potted seedlings in Antalya province of Turkey (Table 3). Transplanting was completed within a single day, with both tomato and watermelon seedlings available for transplanting simultaneously. All transplanters operated at a forward speed of 0.4 m/s, consistent with the recommended speeds by manufacturers and previous studies2,8,29The disc-type transplanter was fitted with elastic discs to reduce the risk of seedling damage. The operator placed the seedlings between the discs, which were arranged at a predetermined angle (Fig. 2a). Seedling spacing in the furrow was regulated by markings on the discs.

Transplanters evaluated in this study for potted seedling transplantation under different tillage conditions: (a) disc-type transplanter with elastic discs to minimize seedling damage and markings for spacing adjustment, (b) carousel-type transplanter with automated seedling placement and press wheels for compression, and (c) dibble-type transplanter with a funnel mechanism for precise seedling deposition.

Carousel and dibble-type transplanters were designed to address synchronization issues between the operator and the planting mechanism. The operator’s role was limited to loading seedlings into the magazine, with subsequent operations automated. Spacing adjustments were made by altering the magazine drive’s transmission ratio8. In carousel-type transplanters, seedlings fell freely into the furrow and were compressed by press wheels (Fig. 2b).

In the dibble-type transplanter, seedlings were inserted into a funnel by the operator. As the funnel’s lower part contacted the soil, it opened, depositing the seedling (Fig. 2c). Both carousel and dibble-type transplanters facilitate faster seedling placement and reduce the need for precise timing compared to the disc-type transplanter. They are typically used for planting potted seedlings in a semi-automatic operation mode.

The furrow opening, closing, and compressing mechanisms varied among the transplanters used in this study. The disc-type and carousel-type transplanters were equipped with shoe-type furrow openers, while the dibble-type transplanter used a funnel mechanism that created an opening before depositing the seedling. For furrow closing and soil compression, the disc-type and carousel-type transplanters employed a metal press wheel, whereas the dibble-type transplanter used a plastic wheel to ensure proper soil coverage around the seedlings.

Experimental design

The experiment was conducted using a split-plot experimental design, where tillage methods were assigned to the main plots, and transplanter types were assigned to the subplots. Before applying the F-test for variance analysis, tests for normality, homoscedasticity, and independence of errors were performed to ensure the validity of the statistical analysis. Duncan’s Multiple Range Test was then applied to determine significant differences among treatment means. The experimental area was divided into four main plots and three subplots per seedling type (tomato or watermelon), with treatments randomly assigned within each plot, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Each plot measured 14 m × 22 m.

Post-transplanting measurements were conducted, and the collected data were assessed based on the parameters outlined by Karayel et al.2, Dihingia et al.9, and Javidan and Mohammadzamani10 to evaluate transplanter performance. The results were then subjected to statistical analysis.

Layout of the experimental design used for evaluating transplanting methods with tomato and watermelon seedlings. The randomized complete block design included four main plots (Conventional 1, Conventional 2, Conservation 1, and Conservation 2) and three subplots per plot (disc-type, carousel-type, and dibble-type transplanters).

Evaluation of transplanter performance

Seedlings were meticulously transplanted into 22-meter-long furrows, with a minimum of eight tomato rows and sixteen watermelon rows per experimental treatment. Transplanter settings were calibrated in accordance with the seedling producers’ recommended spacing. The row spacing was set at 700 mm for all transplanters. The theoretical within-row spacing between consecutive seedlings for tomatoes was 500 mm for the carousel-type and disc-type transplanters and 520 mm for the dibble-type transplanter. The corresponding within-row spacings for watermelons were 1000 mm for the carousel-type and disc-type transplanters and 1040 mm for the dibble-type transplanter. To assess the accuracy of the transplantation process, seedling distances were measured, and subsequent calculations of average spacing and coefficient of variation were performed. The coefficient of variation in seedling spacing was then evaluated against established standards2.

The target transplanting depth for both tomato and watermelon seedlings was 100 mm. Seedling root depths were measured in the vertical plane. A total of 40 randomly chosen seedlings from each row were measured. Average planting depth and its coefficient of variation were computed. According to Karayel et al.2, Karayel and Aytem3, and Javidan and Mohammadzamani10, the transplanter coulter should open the furrow or hole to a depth of up to 150 mm, with an average coefficient of variation in planting depth not exceeding 15%.

To assess soil adhesion, seedlings were pulled from the furrow approximately ten days post-transplanting. The seedling gripping force was measured using a hand-held digital force gauge, which recorded the maximum force required to extract the seedlings from the soil. For acceptable transplanting quality, the minimum gripping force should exceed 3 N2,3. The vertical angle of 30 randomly selected seedlings from each row was measured to determine if they were planted correctly. A fundamental criterion for acceptable transplanting quality is that seedlings maintain a vertical orientation, with an angular deviation not exceeding 30°2,3.

After transplantation, 40 randomly selected seedlings were inspected for damage. Acceptable transplanting methods should not result in more than 3% damage. Damage is defined as the loss of more than one leaf from the seedling2,3. Seedling survival rates were determined four days following transplantation by calculating the ratio of viable seedlings to the total number transplanted. In accordance with conventional practice2,3,8, a minimum survival rate of 90% is considered acceptable for effective transplanting operations.

Results and discussion

The study evaluated seedling spacing for tomato and watermelon seedlings across different transplanter types and tillage methods. The results presented in Table 5. show that the seedling spacing for tomato seedlings varies slightly among the three transplanter types (Disc, Carousel, and Dibble) across the four tillage methods (Conventional 1 and 2, and Conservation 1 and 2). For tomato seedlings, the disc-type transplanter exhibited the widest range in spacing, from 519.5 ± 36.9 mm in Conventional 2 to 544.4 ± 48.5 mm in Conservation 1, while the Dibble-type transplanter had the most consistent spacing with the lowest coefficients of variation (CVs) between 4.43% and 5.62%. Despite these variations, no statistically significant differences were observed in spacing across the transplanters and tillage methods. Similarly, for watermelon seedlings, the disc-type transplanter also showed the widest range in spacing, from 1080.1 ± 80.1 mm in Conventional 2 to 1098.6 ± 97.9 mm in Conservation 1, with the Dibble transplanter again demonstrating the most consistent spacing, with CVs ranging from 4.23 to 5.98%. As with the tomato seedlings, no significant differences were found in spacing among the transplanters and tillage methods for watermelon seedlings.

The findings indicate that tillage methods and transplanter types had a negligible impact on the consistency of seedling spacing for both tomato and watermelon seedlings, as evidenced by the nonsignificant differences in spacing across the treatments. This suggests that all three transplanter types—Disc, Carousel, and Dibble—are capable of maintaining consistent spacing under varying tillage conditions, which is an important factor for uniform crop establishment and growth.

The relatively low coefficients of variation, particularly for the dibble-type transplanter, indicate that this type may provide slightly more uniform spacing compared to the other transplanters. This consistency is essential for ensuring that seedlings have adequate space for root and canopy development, which can directly influence crop yield and quality.

The absence of significant differences among the tillage methods suggests that the choice of the tillage method (Conventional or Conservation) does not markedly affect the ability of these transplanters to achieve consistent spacing. This could imply that other factors, such as the transplanters’ mechanical settings, might play a more crucial role in determining seedling spacing than the tillage method alone.

These results are consistent with the findings of previous studies by Karayel et al.2 and Dihingia et al.9 that have shown the importance of mechanical settings and transplanter design in achieving uniform seedling spacing, regardless of the tillage system employed. However, the lack of significant differences in this study also highlights the potential for flexibility in tillage practices when using these transplanters, allowing farmers to choose tillage methods based on other agronomic or environmental considerations without compromising seedling spacing uniformity.

Table 6. presents the transplanting depths for tomato seedlings, which varied across the three transplanter types and the four tillage methods. In Conventional 1 and 2 tillage methods, the transplanting depths were relatively consistent across the transplanters, ranging from 104.4 ± 8.2 mm to 110.7 ± 9.1 mm, with coefficients of variation (CVs) between 8.10% and 8.25%. However, in the Conservation 1 and 2 tillage methods, significant differences were observed. The disc and carousel-types transplanters showed similar depths, around 90.2 mm to 96.1 mm, with CVs ranging from 11.90 to 12.82%, while the dibble-type transplanter had significantly shallower transplanting depths of 56.1 ± 11.0 mm in Conservation 1 and 55.5 ± 10.8 mm in Conservation 2, with much higher CVs of 19.45–19.66%. These differences were statistically significant, indicating a strong effect of the tillage method on transplanting depth consistency for the dibble-type transplanter (P < 0.01).

A similar trend was observed for watermelon seedlings. In the Conventional 1 and 2 tillage methods, transplanting depths were relatively uniform across transplanters, ranging from 103.7 ± 8.6 mm to 110.5 ± 9.7 mm, with CVs between 8.03% and 8.77%. In contrast, for the Conservation 1 and 2 tillage methods, the disc and Carousel-types transplanters again showed consistent depths of around 90.5 mm to 96 mm, with CVs between 10.77% and 12.55%, while the dibble-type transplanter exhibited significantly shallower transplanting depths of 54.1 ± 10.3 mm in Conservation 1 and 50.5 ± 10.1 mm in Conservation 2, with higher CVs of 19.05–19.74%. These differences were also statistically significant, confirming that the conservation tillage methods affected the dibble-type transplanter more (P < 0.01).

The results indicate that the transplanting depth of seedlings is influenced by both the type of transplanter and the tillage method used. In conventional tillage systems, all three transplanters performed similarly, with consistent transplanting depths and low coefficients of variation, suggesting that these tillage methods provide a stable soil environment that supports uniform transplanting. However, the Conservation 1 and 2 tillage methods presented challenges, particularly for the dibble-type transplanter. As per Karayel et al.‘s2 findings, the CVs measuring the consistency of transplanting depth should not exceed 15%. The CVs of the dibble-type transplanters for conservative tillage conditions in Table 6. are above 15% and are not within acceptable limits. The significant reduction in transplanting depth and the increase in variability observed with the dibble-type transplanter in these conservation systems could be attributed to the less aggressive soil preparation associated with conservation tillage, which may not adequately prepare the seedbed for uniform transplanting. The shallower depths and higher variability in the dibble-type transplanter under conservation tillage might result from insufficient soil disturbance, leading to inconsistent penetration and planting depth.

The significant differences in transplanting depth between the transplanters under conservation tillage methods suggest that the dibble-type transplanter may be less suitable for use in such systems, where maintaining consistent planting depth is crucial for seedling establishment. In contrast, the disc-type and carousel-type transplanters demonstrated greater adaptability to the varying soil conditions present in conservation tillage, maintaining more consistent transplanting depths. The study underscores the need for careful consideration of both tillage practices and transplanter selection to ensure uniform transplanting depth, which is critical for the success of transplanted crops.

This finding is consistent with previous studies that have reported similar effects of tillage practices on seeding depth and seedling establishment when using seeders. For example, Ozmerzi et al.30and Karayel and Ozmerzi31 observed that conservation tillage methods often result in less soil disturbance and less uniform seedbed preparation, which can negatively affect the seeding depth and seedling establishment of precision seeders. Their studies indicated that seeders operating in conservation tillage systems may face challenges in maintaining consistent planting depth due to reduced soil looseness and altered surface conditions. The present research observed a similar effect of tillage methods for transplanters.

The analysis of seedling gripping force, as detailed in Table 7., reveals significant differences among various tillage methods and transplanter types for both tomato and watermelon seedlings. For tomato seedlings, conventional tillage resulted in gripping forces ranging from 16.8 ± 6.7 N with the dibble transplanter to 23.8 ± 10.7 N with the carrousel transplanter. Under the tillage methods of Conservation 1 and 2, gripping forces varied between 11.8 ± 9.6 N (dibble transplanter) and 24.2 ± 10.9 N (carrousel transplanter). For watermelon seedlings, conventional tillage produced forces from 14.5 ± 6.9 N with the dibble transplanter to 21.4 ± 9.9 N with the carrousel transplanter. In Conservation 1 and 2 tillage, forces ranged from 11.5 ± 9.9 N (dibble transplanter) to 15.8 ± 7.1 N (disc-type transplanter).

Achieving high-quality transplanting requires seedlings to be firmly pressed and compacted to prevent dislodgement (rooting out) from the soil under a pulling force of less than 3 N. Proper seedbed preparation and well-designed soil-engaging components in transplanters are essential for ensuring stability, enhancing root-soil contact, and supporting successful seedling establishment2,24,25. The gripping forces of the seedlings presented in Table 7. for all tillage methods and transplanters exceed 3 N and fall within the acceptable range.

The gripping force required to hold seedlings post-transplanting was significantly different across both tillage methods and transplanter types. Conventional Tillage Methods generally resulted in higher gripping forces compared to Conservation Tillage Methods. This is likely due to the more thorough soil preparation and better seedbed conditions provided by conventional tillage, which facilitates more robust anchoring of seedlings. Wasaya et al.32observed similar patterns, noting that conventional tillage creates a more uniform soil structure that better supports seedling establishment and reduces the need for high gripping forces. In contrast, conservation tillage, which typically leaves residue and has less soil disturbance, resulted in lower gripping forces. This finding is consistent with the studies of Çay and Aykas23 and Zhang et al.33, which indicate that reduced soil disturbance in conservation tillage can result in weaker seedling anchorage due to less compacted soil. Çay and Aykas23 further emphasized the impact of different seedbed preparation methods and cover crop applications on the transplanting quality of tomatoes, highlighting the crucial role of optimized soil conditions in enhancing transplanting performance.

Dibble-type transplanters consistently showed lower gripping forces compared to disc-type and carrousel transplanters across both tillage methods. This is consistent with Karayel et al.2, who reported that dibble-type transplanters, while effective for certain applications, often struggle with consistent seedling holding force due to their design, which can result in weaker seedling anchorage. Disc-type and carrousel-type transplanters generally provided higher gripping forces, with disc-type transplanters performing slightly better than carrousel-type. This suggests that transplanters with better soil engagement and more effective gripping mechanisms can enhance seedling stability. Javidan and Mohammadzamani10 noted that transplanters with better soil interaction and adjustment features are more effective in maintaining seedling stability, especially under varied tillage conditions.

The vertical positioning of seedlings, which refers to the angle at which a seedling is planted relative to the vertical axis, varied significantly depending on the tillage methods and the types of transplanters used (Table 8.). For tomato seedlings, conventional tillage methods (Conventional 1 and Conventional 2) generally resulted in a lower vertical positioning compared to conservation tillage methods (Conservation 1 and Conservation 2). A similar trend was observed for watermelon seedlings, where conventional tillage methods also yielded lower vertical positions compared to conservation methods. These findings suggest that conventional tillage practices may contribute to more consistent seedling placement, which is essential for ensuring proper stability and growth. In contrast, conservation tillage methods, particularly when used with dibble-type transplanters, often resulted in higher vertical seedling positions. This outcome suggests that conservation tillage may lead to less precise seedling placement due to reduced soil disturbance and increased variability.

The use of disc-type and carousel-type transplanters was associated with higher vertical seedling positions. This can be attributed to the mechanism of these transplanters, which open a furrow and place the seedling within it. Conversely, the dibble-type transplanter, which places seedlings into holes, tended to decrease the vertical angle of the seedlings. To address this issue, it is suggested that the design of the press wheel on disc-type and carousel-type transplanters be reconsidered. Modifications to the press wheel could potentially improve the vertical positioning of seedlings, thereby enhancing overall seedling establishment and crop performance. Future research should explore alternative press wheel designs that provide better control over seedling verticality, particularly in varying soil conditions, to optimize the effectiveness of these transplanter models. These findings align with the results reported by Karayel et al.2and Javidan and Mohammadzamani10, who observed comparable outcomes for dibble-type transplanters used to transplant tomato seedlings at a depth of 100 mm. Additionally, they highlighted that both the speed and depth of transplanting have a significant effect on the vertical angle of the seedlings.

Karayel et al.2 suggest that the vertical angle of the transplanted seedlings should be kept below 30° to ensure optimal transplanting performance. The average angle data obtained from all three transplanter types across both conventional and conservation tillage methods remained below this threshold, indicating that the transplanting quality was within acceptable standards.

The seedling damage rate following transplanting provides valuable insights into how different tillage methods and transplanter types affect seedling health and survival. The data reveal a pronounced impact of transplanter type on the damage rate for both plant seedlings, while the effects of tillage methods were less significant (Table 9.).

For tomato seedlings, higher damage rates were observed with disc and carousel transplanters across all tillage methods, whereas dibble transplanters consistently resulted in significantly lower damage rates. Specifically, the damage rates with disc transplanters ranged from 7.2 to 7.5%, and with carousel transplanters from 2.5 to 3.0%. In contrast, dibble transplanters achieved a damage rate of less than 0.1% in all cases. These results suggest that dibble transplanters are more effective at minimizing seedling damage, likely due to their design, which limits soil disturbance and allows for more precise seedling placement. A similar pattern was observed for watermelon seedlings, where disc and carousel transplanters exhibited higher damage rates, with disc transplanters causing the most damage (ranging from 7.5 to 8.1%). Conversely, dibble transplanters again demonstrated superior performance, causing less than 0.1% damage. This indicates that dibble transplanters are also more effective at reducing damage to watermelon seedlings, likely due to their gentler handling process.

The overall significance of these findings is that the type of transplanter is a critical factor in seedling survival, with dibble transplanters consistently outperforming others in minimizing seedling damage across all tillage methods.

Kumar and Raheman29, Karayel et al.2, and Javidan and Mohammadzamani10 have recommended that transplanters should not inflict damage exceeding 3% on seedlings. As indicated in Table 9., only the disc-type transplanter surpassed this limit for both tomato and watermelon seedlings. This heightened damage can likely be attributed to the positioning of just the leafy sections of the seedlings between the elastic discs of the transplanter. Given that the potted roots are heavier than the leaves, the latter struggle to adequately support the weight of the roots, resulting in increased damage. In contrast, the dibble-type transplanters exhibited the lowest damage rates.

The data presented in Table 9. shed light on the impact of various transplanter types and tillage methods on seedling survival rates following transplanting. The analysis reveals significant differences in survival rates, particularly when comparing the performance of dibble transplanters with that of disc and carousel transplanters.

The findings indicate that dibble transplanters tend to result in lower survival rates for both tomato and watermelon seedlings compared to disc and carousel transplanters, especially under conservation tillage methods. This trend is observed across both conventional and conservation tillage systems, with notably lower survival rates for tomato seedlings when dibble transplanters are used in conservation tillage conditions. A similar pattern emerges for watermelon seedlings. These results diverge from previous studies that have emphasized the benefits of dibble transplanters for seedling survival. For example, research by Khadatkar et al.8, and He et al.34 suggested that dibble transplanters should generally yield higher survival rates due to their gentle planting mechanisms. However, the outcomes of this study may be influenced by specific operational factors or environmental conditions that are not universally applicable. For instance, studies by Iqbal et al.35 and Zhao et al.36 reported that dibble transplanters might lead to lower survival rates in highly compacted or inadequately prepared soils, which could correspond to the conditions encountered in this study’s conservation tillage scenarios.

Regarding the influence of tillage methods on seedling survival, the results show that conservation tillage methods lead to significantly lower survival rates for both types of seedlings when using dibble transplanters. According to Karayel et al.2and Çay and Aykas23, the minimum acceptable survival rate for vegetable seedlings should be 90%. However, the average survival rates for both plant seedlings fell below this threshold when the dibble transplanter was used in conservation tillage systems (Table 9.). The minimal soil disturbance characteristic of conservation tillage methods may not always create optimal conditions for seedling establishment, particularly when combined with dibble transplanters, which may not perform effectively under such conditions.

The study demonstrates that while seedling spacing remains unaffected by transplanter type or tillage method, other critical performance metrics such as transplanting depth, seedling gripping force, vertical seedling position, damage rate, and survival rate exhibit significant variations. Notably, dibble transplanters, despite their lower seedling damage rates, tend to result in lower survival rates compared to disc and carousel types. This suggests that while dibble transplanters are gentler on seedlings, they may not secure or position them as effectively, particularly under conservation tillage methods. In contrast, disc and carousel transplanters exhibit superior performance in terms of seedling gripping force and positioning, albeit with higher damage rates. These results demonstrate that conservation tillage methods are particularly well-suited for use with disc and carousel transplanters, offering a viable alternative that enhances seedling establishment. However, these methods are less effective when paired with dibble-type transplanters, which demand more precise handling and positioning. This study underscores the critical importance of aligning transplanter design with appropriate tillage methods to optimize seedling establishment and crop performance. It highlights the need for tailored equipment and soil preparation practices to meet specific planting conditions.

The novelty of this research lies in its comprehensive evaluation of the interaction between transplanter mechanisms and tillage methods. By identifying the strengths and limitations of each transplanter type across different tillage scenarios, this study provides actionable insights for improving seedling establishment. It establishes a robust framework for aligning equipment design and soil preparation strategies to achieve optimal transplanting performance under diverse agricultural conditions.

Conclusion

This study elucidates the differential effects of tillage methods on the performance of disc, carousel, and dibble-type transplanters. While all transplanter types achieve consistent seedling spacing across various tillage methods, significant variations in transplanting depth and gripping force are observed. Conventional tillage methods generally support more uniform transplanting depths and higher gripping forces, contributing to improved seedling stability and reduced damage. In contrast, conservation tillage methods, particularly with dibble-type transplanters, result in shallower planting depths and greater variability, potentially hindering seedling establishment. The lower seedling damage rates associated with dibble-type transplanters highlight their capacity to minimize injury during planting. However, their reduced survival rates under conservation tillage conditions indicate challenges in less disturbed soils. Conversely, conservation tillage methods prove effective for disc and carousel transplanters, enhancing seedling establishment without compromising survival rates.

The novelty of this research lies in its systematic evaluation of the interplay between transplanter mechanisms and tillage methods, providing actionable insights for optimizing seedling establishment across diverse agricultural conditions. By identifying the strengths and limitations of different transplanter types in varying tillage scenarios, this study establishes a foundation for aligning equipment design and soil preparation practices to improve transplanting performance and crop sustainability. Furthermore, the findings the optimal combinations of tillage methods and transplanter models that enhance transplanting efficiency and seedling establishment, offering valuable guidance for farmers and agricultural engineers in selecting appropriate soil preparation and transplanting equipment to improve crop production and sustainability. Future research should focus on enhancing the adaptability of dibble-type transplanters to conservation tillage systems and further examining the interaction between soil conditions, tillage methods, and transplanter mechanisms to refine practical recommendations for sustainable crop production.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CV:

-

Coefficients of variation (%)

- EC:

-

Electrical conductivity (dS/m)

- ns:

-

Statistically nonsignificant differences

- P:

-

Probability associated with a statistical test

References

Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma 123 (1–2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.01.032 (2004).

Karayel, D. et al. Technical evaluation of transplanters’ performance for potted seedlings. Turkish J. Agric. Forestry. 47 (1), 116–123. https://doi.org/10.55730/1300-011X.3068 (2023).

Karayel, D. & Aytem, H. The effect of different tillage methods on transplanting quality of potted tomato and watermelon seedlings. Journal of Agricultural Machinery Science, 9 (1): 83 91 (in Turkish with an abstract in English) (2013).

Chaurasia, S. N. S., Bahadur, A., Sharma, S., Krishna, H. & Singh, S. K. Nursery management in vegetable crops for enhancing farmers’ income. Indian Hortic. 68 (2), 33–38 (2023).

Sharma, A. & Khar, S. Design and development of a vegetable plug seedling transplanting mechanism for a semi-automatic transplanter. Sci. Hort. 326, 112773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112773 (2024).

Gallegos-Cedillo, V. M. et al. An in-depth analysis of sustainable practices in vegetable seedlings nurseries: A review. Sci. Hort. 334, 113342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113342 (2024).

Murray, J. R., Tullberg, J. N. & Basnet, B. B. Planters and their components: types, attributes, functional requirements, classification and description. ACIAR Monograph, No. 121. ISBN online: 1 86320 463 6 (2006).

Khadatkar, A., Mathur, S. M. & Gaikwad, B. B. Automation in transplanting. Curr. Sci. 115 (10), 1884–1892 (2018).

Dihingia, P. C., Kumar, G. V. P. & Sarma, P. K. Development of a hopper type planting device for a walk-behind hand-tractor-powered vegetable transplanter. J. Biosystems Eng. 41, 21–33. https://doi.org/10.5307/JBE.2016.41.1.021 (2016).

Javidan, S. M. & Mohammadzamani, D. Design, construction and evaluation of semi-automatic vegetable transplanter with conical distributor cup. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1034-y (2019).

Pearsons, K. A., Omondi, E. C., Zinati, G., Smith, A. & Rui, Y. A Tale of two systems: does reducing tillage affect soil health differently in long-term, side-by-side conventional and organic agricultural systems? Soil Tillage. Res. 226, 105562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105562 (2023).

Pittarello, M., Dal Ferro, N., Chiarini, F., Morari, F. & Carletti, P. Influence of tillage and crop rotations in organic and conventional farming systems on soil organic matter, bulk density and enzymatic activities in a short-term field experiment. Agronomy 11 (4), 724. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11040724 (2021).

Wulanningtyas, H. S. et al. A cover crop and no-tillage system for enhancing soil health by increasing soil organic matter in soybean cultivation. Soil Tillage. Res. 205, 104749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2020.104749 (2021).

Hobbs, P. R., Sayre, K. & Gupta, R. The role of conservation agriculture in sustainable agriculture. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 363 (1491), 543–555. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2169 (2008).

Pimentel, D. et al. Environmental and economic costs of soil erosion and conservation benefits. Science 267 (5203), 1117–1123 (1995).

Zhang, Y., Tan, C., Wang, R., Li, J. & Wang, X. Conservation tillage rotation enhanced soil structure and soil nutrients in long-term dryland agriculture. Eur. J. Agron. 131, 126379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2021.126379 (2021).

Du, C., Li, L. & Effah, Z. Effects of straw mulching and reduced tillage on crop production and environment: A review. Water 14 (16), 2471. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14162471 (2022).

Askari, M. et al. Applying the response surface methodology (rsm) approach to predict the tractive performance of an agricultural tractor during semi-deep tillage. Agriculture 11 (11), 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111043 (2021).

Abo-Habaga, M., Ismail, Z. & Okasha, M. Effect of tillage systems on a soil moisture content and crops productivity. J. Soil. Sci. Agricultural Eng. 13 (7), 231–235. https://doi.org/10.21608/jssae.2022.138432.1077 (2022).

Han, L., Mao, H., Hu, J. & Kumi, F. Development of a riding-type fully automatic transplanter for vegetable plug seedlings. Span. J. Agricultural Res. 17 (3), e0205–e0205. https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2019173-15358 (2019).

Morse, R. D., Vaughan, D. H. & Belcher, L. W. Evolution of conservation tillage systems for transplanted crops; Potential role of the subsurface tiller transplanter (SST-T). Proceedings Southern Region Conservation Tillage for Sustainable Agriculture, 145–151 (1993).

Frasconi, C. et al. A field vegetable transplanter for use in both tilled and no-till soils. Trans. ASABE. 62 (3), 593–602. https://doi.org/10.13031/trans.12896 (2019).

Çay, A. & Aykas, E. Domates üretiminde Farklı Fide Yatağı Hazırlığı yöntemleri ve Örtü Bitkisi Uygulamasının verim ve Hasat Sonrası Kalite parametrelerine etkileri (Effects of different Seedling-bad preparations and cover crop application on yield and Post-Harvest quality parameters in tomato Production). Tekirdağ Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi (Journal Tekirdag Agricultural Faculty). 10 (1), 105–114 (2013).

Miah, M. S. et al. Design and evaluation of a power tiller vegetable seedling transplanter with Dibbler and furrow type. Heliyon 9 (8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17827 (2023).

Jiang, L. et al. Design and test of seedbed Preparation machine before transplanting of rapeseed combined transplanter. Agriculture 12 (9), 1427. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12091427 (2022).

Al-Shammary, A. A. G., Al-Shihmani, L. S. S., Caballero-Calvo, A. & Fernandez-Galvez, J. Impact of agronomic practices on physical surface crusts and some soil technical attributes of two winter wheat fields in Southern Iraq. J. Soils Sediments. 23, 3917–3936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-023-03585-w (2023).

Afshar, R. K. et al. Corn productivity and soil characteristic alterations following transition from conventional to conservation tillage. Soil Tillage. Res. 220, 105351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105351 (2022).

Franzluebbers, A. J. Soil organic matter, texture, and drying temperature effects on water content. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 86 (4), 1086–1095. https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20425 (2022).

Kumar, G. V. P. & Raheman, H. Vegetable transplanters for use in developing countries: a review. Int. J. Vegetable Sci. 14 (3), 232–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315260802164921 (2008).

Özmerzi, A., Karayel, D. & Topakci, M. Effect of sowing depth on precision seeder uniformity. Biosyst. Eng. 82 (2), 227–230. https://doi.org/10.1006/bioe.2002.0057 (2002).

Karayel, D. & Ozmerzi, A. Effect of tillage methods on sowing uniformity of maize. Can. Biosyst. Eng. 44, 2–23 (2002).

Wasaya, A., Yasir, T. A., Ijaz, M. & Ahmad, S. Tillage effects on agronomic crop production. In Agronomic Crops (ed. Hasanuzzaman, M.) (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9783-8_5.

Zhang, B., Jia, Y., Fan, H., Guo, C., Fu, J., Li, S., … Ma, R. Soil compaction due to agricultural machinery impact: A systematic review. Land Degradation & Development, 35(10), 3256–3273. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.5144 (2024).

He, F., Deng, G., Cui, Z., Li, L. & Li, G. Development of a rotary dibble-type cassava planter. Engenharia Agrícola. 42 (5), e20210237. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4430-Eng.Agric.v42n5e20210237/2022 (2022).

Iqbal, M. Z. et al. Working speed analysis of the gear-driven dibbling mechanism of a 2.6 kw walking-type automatic pepper transplanter. Machines 9 (1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines9010006 (2021).

Zhao, X. et al. Study on the Hole-Forming performance and opening of mulching film for a Dibble-Type transplanting device. Agriculture 14 (3), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14030494 (2024).

Funding

This project has received funding from the Ministry of Education, Science and Sports of the Republic of Lithuania and Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT) under the Program ‘University Excellence Initiative’ Project ‘Development of the Bioeconomy Research Center of Excellence’ (BioTEC), agreement No S-A-UEI-23-14.

Additionally, this research was partially funded by the Scientific Research Projects Administration Unit of Akdeniz University, Antalya, TR, through Project No. 2011.02.0121.015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: HA, DK, and EŠ; formal analysis: HA and DK; investigation: HA and DK; methodology: HA, DK, and EŠ; project administration: DK; supervision: DK; funding acquisition: DK and EŠ; writing—original draft: HA, DK, and EŠ; writing—review and editing: DK and EŠ. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aytem, H., Karayel, D. & Šarauskis, E. Influence of tillage methods on transplanter performance with different transplanting mechanisms. Sci Rep 15, 13081 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98146-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98146-1