Abstract

This study assessed the preliminary results of an experimental protocol evaluating the impact of positive expectations on fingertip-to-floor distance during forward bending. Thirty-six participants were assigned to three groups, each receiving a sham physical manipulation in Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR). The first group received a neutral statement about the manipulation’s efficacy, while the second and third groups were told the manipulation would improve forward bending, emphasising its fictious positive effect to increase expectations for a beneficial motor improvement. Additionally, the third group also experienced a visual-haptic illusion, by lifting a tile in front of participants and raising the floor in the virtual scenario, creating the belief of reaching the floor thanks to the received manipulation. Fingertip-to-floor distance was measured at baseline, immediately after the manipulation (after-effect), and five minutes later (follow-up). Differences between baseline and after-effect/follow-up distances represented the gained distances. Only the third group, which experienced the combined effect of positive verbal statement reinforced by the visual-haptic illusion, showed a significant increase in gained distance during the after-effect and follow-up phases compared to the neutral statement group. These findings support the potential of this multifactorial intervention to promote motor improvement by enhancing positive expectations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human motion is the result of the interaction between the musculoskeletal apparatus and the central and peripheral nervous systems1. They cooperate via a complex integration of sensory-motor, emotional and cognitive inputs, resulting from top-down and bottom-up processes2 to adapt human motor responses to everyday tasks3,4. The context in which movement occurs is characterised by internal (e.g., psycho-biological aspects like personality traits and genetics) and external (e.g., physical and social aspects of the environment) factors. These factors, together with previous individual experiences, social interactions, beliefs, and internal states play a key role in influencing physiological and behavioural responses5,6,7,8 through an internal inferential model that can be linked to the so called “Predictive Processing” theory9,10.

The Predictive Processing model describes the brain as a dynamic system11,12,13,14 continuously aiming to minimise predictive errors by comparing expected inputs (i.e., expectations) with the afferent multi-sensory stimulation to optimise interaction with the environment in terms of perception, decision making, and motor control15,16.

Various formulations of predictive processing have been proposed17, ranging from early hierarchical models18,19,20 stemmed from Bayesian theory21,22 to more comprehensive and dynamic frameworks11,23,24 that extend beyond brain-based computation to incorporate dynamic interactions among the brain, body, and environment.

In this context, the “Perceptual Inference” model provide a possible method to reduce prediction errors25,26. In this model, more weight is given to actual afferent multi-sensory information than to “Priors” (i.e., the previously consolidated view of the situation), resulting in new “Posteriors” (i.e., an updated view of the situation) used to interpret future events. Additionally, research indicates that verbal instructions can influence motor responses, even without prior direct experience of an action’s effects27, modulating attention, response selection, and cognitive biases28. These findings suggests that verbal cues are integrated with sensory experiences29 to shape and adjust Priors30, influencing how individuals interact with the environment.

In recent years, Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR) has been widely exploited in research31,32,33 as a promising tool that can alter the contextual perception of the person immersed in terms of temporal and spatial references34. Thus, from the perspective of the Predictive Processing framework, IVR can be seen as an effective method for influencing a person’s expectations (Priors), ultimately affecting their functional outcomes (Posteriors).

Here, relying on the principles of Perceptual Inference, we propose that, IVR can effectively shape a person’s pre-existing movement expectations, leading to improved movement strategies and better motor outcomes. This general idea could be especially useful in actively challenging negative expectations about one’s own health that can lead into erroneous beliefs aimed at avoiding pain, known as fear-avoidance beliefs35. This negative mindset can contribute to an irrational fear of physical movement, also known as kinesiophobia36, leading to a reduced mobility. This phenomenon is well documented in musculoskeletal conditions and particularly for chronic low back pain37.

Motivated by the potential for future clinical application in chronic low back pain, and considering the difficult that this population experiences during lumbar movements38, we conducted a preliminary pilot study on healthy people to test whether positive verbal feedback and immersive visual-haptic stimuli could enhance expectations (priors) and improve fingertip-to-floor distance in a forward bending exercise.

Methods

Trial design

This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and it is here reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials - CONSORT (see Supplementary file) for pilot and feasibility trial39. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee for University Research (CERA: Comitato Etico per la Ricerca di Ateneo), University of Genova (approval date: 12/11/2020; CERA2020.23).

Participants

Participants were recruited from a convenience sample of healthy people. Eligibility was determined based on the following inclusion criteria: (a) no history of neurological, vestibular, rheumatic, or musculoskeletal diseases, and no reported low back pain in the previous six months that impacted daily activities, work (e.g., absenteeism), or necessitated medical or physiotherapy intervention; (b) aged between 18 and 55 years old, and (c) the ability to reach a distance of at least 25 cm from the floor (maximum extension of the movable tile, see Chap. 2.3 Intervention), as measured by the Fingertip-to-Floor Test40. Informed consent was presented in a written form and obtained from all participants before the experiment.

Sample size

Considering the exploratory nature of the study, a sample size of 12 participants per group was recruited, as suggested by Julious41.

Blinding procedure

Participants did not know which group they were assigned to. As reported above, all participants received before the onset of the study the same explanation about the experimental aims.

Interventions

Experimental protocol

Our study followed an experimental design often used in placebo research, which aims at exploring the role of participants’ beliefs in an intervention42. This is accomplished by providing a population with an ineffective treatment (or no treatment) without their knowledge, to examine the impact of individual expectations and beliefs alone. In our case, to cover the real purpose of this study, consisting in the administration of positive expectations induced by different verbal and perceptive virtual stimuli to reduce the fingertips-to-floor distance during forward bending, a fictitious clarification of the study was provided to all participants once they arrived at the laboratory:

“The goal of this study is to evaluate whether Virtual Reality can be used as a tool to measure in real-time, changes in the mobility of the spinal column. We will take the measurements both with a manual instrument and with virtual reality, to see how much difference there is between the accuracy of these two measurements.”

The real aim of the study was disclosed to each participant only at the end of the experimental session.

All participants performed a series of forward bends while standing on a rigid cubic structure of (50 × 50 × 7 cm). This solution was adopted to increase the distance from the floor to facilitate the measurements also in those participants that nearly reached the ground. Starting from a standing stance position with the feet together, the participants were explicitly verbally instructed to bend forward maintaining the elbows and the knees extended, with the palms of the hands together, reaching a target represented by a black “X” mark located at 20 cm from the tip of the toes, positioned along a line painted on the floor. Each forward bend was accompanied by the experimenter’s indications about its execution in both modality and timing (“go down slowly - bend as much as you can - stay – up”).

Following these directives, the participants executed 30 warming-up forward bends before the experiment started. The first 15 were utilised as an additional exclusion criteria to make sure that the participant did not easily reach the floor (potentially resulting in a ceiling effect in the measurements), and the last 15, executed before the beginning of the study, to adjust for the eventual mobility gain related to the continuous repetitions of the task43.

After, each participant performed four consecutive trials (Baseline, Intervention, After-Effect, and Follow-Up) according to the specific allocation group: (i) Neutral Expectation Group (G0), (ii) Positive verbal Expectation Group (G+), and (iii) Visual-Haptic illusion + Positive verbal Expectation (G++). Participants were assigned to each group based on their arrival order, with groups being filled consecutively. The four trials were performed in the immersive virtual scenario (see technical characteristics of the system at 2.3.2 – Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR) system and virtual scenario). Each individual stood on a tile with four different floor panels around it, positioned orthogonally to each other, as displayed in Figure 1. The person was asked to turn towards each different panel based on the specific phase of the trial of the trial (Baseline, Intervention, After Effect and Follow-Up). Specifically, the participants performed five forward bends toward each tile, with the experimenter positioned behind the participant to verbally guiding them during the experiment. A sham physiotherapy manoeuvre, consisting of four pressures of 40 N for 10 s. each in four bony sites not directly involved in the back movement (left and right posterior-superior iliac spine, and left and right medial margin of the spina scapulae) was executed in all groups before performing the experimental task towards the “Intervention” tile. The physiotherapy sham manoeuvre was standardised with an algometer Wagner Force OneTM Digital Force Gage (Wagner, Greenwich 2020, USA) and paired with a verbal statement related to its efficacy different for each group.

Tracking area in which the study was performed. Participants executed the whole study by turning inside the area identified by the black square, representing the top view of the rigid cubic structure. The task involved participants performing a forward bending movement and reaching with their hands towards the black X. This task was performed at three different time intervals: Baseline, After-Effect, and Follow-Up.

The experimental protocol differentiated for each group is thoroughly reported in Table 1.

Briefly, in G0 group, the execution of the sham physiotherapy manoeuvre was accompanied by a neutral verbal statement regarding its effectiveness and stated by the experimenter immediately after the end of the manoeuvre. On the contrary, the groups G + and G + + received a positive verbal stimulus regarding its efficacy.

Furthermore, only in the G + + group, after the sham manoeuvre and the positive verbal stimulus, the tile in front of the participants was subtly raised using a mechanical jack, without their knowledge, creating the illusion that they had successfully touched the floor (Fig. 2). The level of the tile was raised to match the fingertip-to-floor distance each participant reached during the Baseline measurement. Independently from the groups, all the sham manoeuvres were conducted by the same experimenter trained by specialised physiotherapists to apply pressures and recognise the specific anatomical marks. Moreover, the same experimenter was also in charge of the assessments of the fingertip-to-floor distance across all participants and experimental trials. A lounge music was played in the background of the laboratory and through the earphones of the head-mounted display in the IVR system. The volume was kept low to allow participants to hear the experimenter’s instructions and was increased only during the activation of the mechanical jack to mask the noise coming from the tile’s movement (Table 1). The same lounge music was played continuously through the earphones of the Head-Mounted Display (HMD) for the entire duration of the study and for all groups to standardize the intervention. After the experimental session and the disclosure of the real purpose of the study, participants were asked to report if they become aware of the illusion and if they had heard any noise during the lifting of the tile during the repeated performance of the task. All participants confirmed that they did not notice the movement of the tile, reporting that the music volume was loud enough to mask any sound produced during its lifting.

Participant’s Perception of the Forward Bending Task during the Visual-Haptic Illusion in Immersive Virtual Reality (G + + Group). (On the left) Visual-haptic illusion implementation. (On the center) Virtual simulation experienced by the participant. (On the right) Personal perception intended to be elicited in participants experiencing the visual-haptic illusion.

Immersive virtual reality (IVR) system and virtual scenario

The immersive environment was delivered through the HTC Vive Pro system. This system is based on a full-body tracking technology (SteamVR 1.0 tracking) able to register synchronously the position and orientation of different trackable elements and translate this information into the virtual scenario for realistic visual-haptic feedback44. The implemented apparatus was calibrated over a 2,5 × 2,5 m and included a Vive PRO HMD, two SteamVR 1.0 Lighthouse base stations, and three Vive trackers 2.0 (Valve, Washington, United States, 2018). The HMD was connected to a PC in wireless configuration and participants’ movements were recorded through two Vive trackers positioned with velcro straps on the back of their hands. The virtual scenario (Fig. 3B) was a 1:1 reconstruction of the laboratory in which the participants performed the experiment (Fig. 3A), designed in Unreal Engine 4.25.4.

In this environment, the virtual point of view of the user was adjusted according to the registered height position of the third VIVE tracker positioned over a movable panel on the floor. A schematic representation of the experimental setup is reported in Fig. 3D. To adjust the level of the virtual floor across the experimental trials, the laboratory environment was temporarily masked by displaying a black dummy loading screen (Fig. 3C) with increased background music volume to conceal the sound of the tile movement and the change in the virtual viewpoint of the scene.

Outcome measurements

The main outcome measure of the present study were the gained distance values, obtained for the three different groups (G0, G+, G++) by subtracting the fingertip-to-floor distances obtained in the Baseline with the ones reached at the After-Effect and Follow-Up conditions, as reported below:

Where the x is the fingertip-to-floor distance reached from the floor and the subscripts b, ae, and fu represent the three experimental trials, namely, baseline, after-effect, and follow-up. Out of the five forward bends performed in each trial, the fingertip-to-floor distances were measured only during the final bend using a tape measure.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried in Python 3 (Python Software Foundation, version 3.13.1. Available at http://www.python.org). All explanatory figures were created with GNU Image Manipulation Program 2.10.24 (GIMP) and with Inkscape 1.1.2 (Inkscape Project, 2020. Inkscape, Available at: https://inkscape.org).

Descriptive analysis (age, BMI, gender they identified with) was carried out and reported as mean and standard deviation or percentages as frequencies. The gained distance values and the fingertip-to-floor distances were reported as median (Q2) with the first quartile and third quartile [Q1, Q3] as indexes of dispersion since data did not follow a normal distribution, after visual inspection of the Q-Q plots (statsmodels module: qqplot)45.

Then, we used the Kruskal-Wallis H-Test to compare the gained distance values [cm] obtained during the After-Effect and the Follow-Up in respect to the Baseline. The post-hoc analyses were performed using pairwise Mann-Whitney U-Tests.

The significance acceptance level for pairwise comparison was adjusted to 0.0125 using the Bonferroni Correction46, with k representing the number of comparisons (k = 3). Effect sizes were calculated as rank biserial correlation coefficients47. We used bootstrapping (500 replications) to compute 95% CI of the effect size across the different interventions. The Python script of the statistical analysis is reported in the Supplementary Data file.

Results

A convenience sample of 58 eligible participants was considered for inclusion and screened for eligibility. Among them, 6 (10,3%) were enrolled to optimise and test the first draft protocol of the study, 2 (3,4%) were excluded for difficulties related to experiences with an IVR environment, such as lack of air and dizziness, and 14 (24,1%) were excluded since they easily reached the floor during the 30 warming-up flexions. Ultimately, thirty-six participants (62%) were considered eligible and included in this study. They were equally assigned to each experimental group (G0, G+, G++). Descriptive characteristics of the three experimental groups are presented in Table 2.

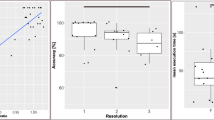

Table 3 reports the medians [Q1, Q3] of the different parameters explored. Overall, the Kruskal-Wallis H-Tests, showed a statistical difference, in terms of gained distance values in relation to the Baseline, between all the different groups in the After-Effect, p = 0.011, and in the Follow-Up, p = 0.030. Post-hoc Mann-Whitney U-tests showed that the gained distance values at the After-Effect and the gained distance values at the Follow-Up differ only in the comparison between the G0 and G + + groups. The gained distance values did not differ in any other group comparison (Table 4). Boxplots for the gained distance values for all three experimental groups are reported in Figs. 4 and 5 respectively.

Boxplot of the gained distance value obtained in the After-Effect for each of the experimental groups. The central line within the box represents the median, while the edges of the box correspond to the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range (± 1.5 * IQR) from the lower and upper quartiles.

Boxplot of the gain distance obtained in the Follow-Up for each of the experimental groups. The central line within the box represents the median, while the edges of the box correspond to the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range (± 1.5 * IQR) from the lower and upper quartiles.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that the use of the IVR system could be a valid and safe instrument to modify the fingertip-to-floor distance during forward bending task in a cohort of healthy people. Hereafter, we are discussing the preliminary results of this study, its future applications in research, and the possible improvements of the present protocol for forthcoming clinical trials.

Our hypothesis was that a positive modification of participants’ expectations induced by the belief of being able to touch the floor would translate into a modification of their motor strategy, enhancing their forward bending and consequently reducing the fingertips-to-floor distance. Our results partially align with our initial hypothesis, highlighting that the verbal and the visual-haptic manipulation can reduce the fingertip-to-floor distance in a cohort of healthy individuals. Specifically, the G + + group and the multisensory nature of its specific intervention (i.e., verbal manipulation, visual-haptic illusion) showed a significant improvement in terms of gained distance values from the G0 group. The role played by inducing positive expectations to increase the performance of motor tasks is in line with a broad array of previous studies48,49,50,51,52,53,54 suggested that the expectancies related to the occurrence of non-volitive responses, called response expectancies, and those related to the own self-efficacy, named self-efficacy expectancies, significantly contribute to the overall placebo and nocebo response. According to Kirsch’s conceptualisation, it is possible to speculate that the presence of these two kinds of expectancies affected the magnitude of the improvement in the gained distance values via a summative effect.

Indeed, in the G + + vs. G0, the combination of a verbal manipulation and the visual-haptic illusion might have induced in the participants a stronger belief that they can successfully reach the floor. Hence, the improvement in the motor performance through the visual-haptic illusion may have tapped into the abovementioned self-efficacy expectancies. Moreover, this fast recalibration of the information might be elicited by the surprise or “wow effect”55, induced by the unexpected possibility of touching the floor as a result of the visual-haptic illusion. Classically, surprise is considered as an emotion that occurs when there is a discrepancy between what is perceived and what is expected, and induces the recalibration of our beliefs, expectations, and behaviours56,57, , inducing specific cortical activations58 and cognitive responses59. The sense of surprise can also be interpreted through the framework of predictive processing57, in which the mismatch between expectations and incoming sensory information must be resolved. As suggested by the cognitive-evolutionary model of surprise57, the schemas that control perception and actions are continuously updated at an unconscious level through the comparing of the incoming information to those possessed (belief).

Moreover, while the G0 group with neutral expectancy reported the lowest gained distance value, the G + group, where the response expectancy was induced through a positive verbal stimulus provided by the experimenter, improved their gained distance values (even if not statistically different) from G0. However, the 95% CI in the effect size in G + vs. G0 was pretty close to a positive value. Despite we did not find a statistical difference between G + and G + + group, probably because of a sample size related problem, a trend was seen in favour of G + + in the comparison of G + and G0.

The results presented should be appraised with caution in the light of specific limitations inherent in the exploratory character of this study. Since this work wanted to test the experiment and its possible outcomes while providing valuable information for improving future research, we have reported the limitations encountered and proposed potential solutions to address them.

The main limitation of this work lies in the measurement methodology of the fingertip-to-floor distance, performed manually by a single experimenter. The experimenter was aware of which group the participants belonged to, and this might have influenced the results with a potential bias. Future developments of this experimental methodology should consider blinding the assessor and the statistician to reduce possible measurement biases. Additionally, previous research showed that fingertip-to-floor test in healthy people has a high degree of variability, with coefficients of variation ranging from 14 to 76%40,60,61. The promising results of our study might justify the use of more sophisticated and expansive measurements technologies (e.g., optoelectronic motion capture systems).

Furthermore, during the time of the experiment, the existing literature on the accuracy of VIVE Trackers for measuring positions using the SteamVR 1.0 tracking systems presented inconsistent findings62. Given this variability and the difficulties associated with a repeatable position of the rather cumbersome trackers on the back of the hand, we made the decision to simply rely on manual assessment of fingertip-to-floor distance. Given the recent advancements in motion tracking technology for IVR systems63, future studies should implement objective methods to evaluate not just the distance achieved from the floor, but also the full-body kinematics during forward bending to describe the complete movement strategy. For instance, with the improved SteamVR 2.0 tracking technology, it is possible to use up to four base stations, which combined with the newer and lighter VIVE trackers 3.0, ensure a better coverage of the recording area and more precise measurements. Another viable solution might be the use of a laser metre firmly fixed to the fingers of the participants.

Another limitation in our measurements is that we only recorded the last repetition of the five forward bends performed by the participants. While it is generally accepted to measure mobility after a steady state is reached, we observed that the gained distances tended to reduce across the different repetitions. This may have led to an underestimation of the immediate impact of the intervention and missed the opportunity to observe the progressive decrement of the distance gain, probably resulting from a violation of the new expectancy induced by the visual-haptic illusion. By adopting more objective and automatic measurements, it would have been possible to conduct multiple assessment within the different time periods. This solution would have provided deeper insights into how the exposure to a multisensory context, as the one proposed in our study, influences participants’ strategy to reduce the fingertips to floor distance.

As mentioned above, we analysed a small sample size, typical of exploratory studies whose aim is to test feasibility rather than interventions’ efficacy. By examining the effect sizes and their 95% CI obtained in the between group comparisons of the distance gains, we can speculate a trend towards the improvement of the effects in favour of the G + group compared to the G0, and in favour of the G + + group compared to the G + group. Therefore, a larger sample size might exalt the difference between our experimental conditions globally, improving the interpretation and relevance of the results.

In our work we did not objectively analyse the evolution of participants’ expectations, limiting to asking whether the participants had become aware of the visual-haptic illusion during the course of the experiment. This can be a starting point for future research aimed at studying more deeply the actual correlation between expectations and motor performance. Quick and easy to administer questionnaires (such as Likert scales) can be integrated into the virtual scenario giving the participant the opportunity to express on-the-go their expectations regarding the effectiveness of the sham manoeuvre64.

Another limitation of our study is the use of a convenience method to allocate participants in each group. Participants were assigned to specific groups based on their order of arrival, without implementing a structured randomisation process. However, the descriptive analysis of the population did not show significant differences between the groups. In this regard, one factor we did not consider is the participants’ initial level of athletic ability and mobility, which could explain the group differences in fingertip-to-floor distances over time and might have influenced the degree of the effect of the different interventions. Future research should assess these factors as potential covariates.

As a final remark, our preliminary investigation did not consider an additional condition where participants should experience the visual-haptic illusion after receiving a neutral statement regarding the efficacy of the sham manoeuvre. This would have helped to understand better the reason behind the differences observed between the three groups.

Our findings represent a promising initial step in exploring the potential of IVR-based interventions to create multisensory contexts that promote positive movement-related expectations and improve motor outcomes.

In this regard, in line with recent literature32, our experimental protocol based on the forward bending task represents an innovative approach that could be particularly valuable for treating chronic low back pain, where negative mindset and fear-avoidance beliefs, are contributing factors of kinesiophobia, and reduced mobility37. Thus, future studies should improve and test our paradigm in a larger sample and in people with restriction in forward bending due to disease-related conditions (e.g., low back pain).

Data availability

The CONSORT checklist, the data supporting the findings of this study and the Python statistical analysis script are included in the Supplementary Data file. The software of the virtual simulation is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Roy, J. S., Bouyer, L. J., Langevin, P. & Mercier, C. Beyond the Joint: The Role of Central Nervous System Reorganizations in Chronic Musculoskeletal Disorders. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther., vol. 47, fasc. 11, pp. 817–821, nov. (2017). https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.0608

Taylor, A. G., Goehler, L. E., Galper, D. I., Innes, K. E. & Bourguignon, C. «Top-Down and Bottom-Up Mechanisms in Mind-Body Medicine: Development of an Integrative Framework for Psychophysiological Research. Explore N. Y. N, vol. 6, fasc. 1, p. 29, gen. (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2009.10.004

Pearson, K. G. Neural adaptation in the generation of rhythmic behavior. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 62 (fasc. 1), 723–753. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.723 (2000).

Vingerhoets, G. & Harrington, D. Introduction to the JINS Special Issue: Motor Cognition. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc., vol. 23, fasc. 2, pp. 103–107, feb. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617717000078

Benedetti, F. Placebo and the New Physiology of the Doctor-Patient Relationship. Physiol. Rev., vol. 93, fasc. 3, pp. 1207–1246, lug. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00043.2012

Carlino, E., Frisaldi, E. & Benedetti, F. Pain and the context. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol., vol. 10, fasc. 6, Art. fasc. 6, giu. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2014.17

Testa e, M. & Rossettini, G. Enhance placebo, avoid nocebo: How contextual factors affect physiotherapy outcomes. Man. Ther., vol. 24, pp. 65–74, ago. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2016.04.006

Wager, T. D. & Atlas, L. Y. The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat. Rev. Neurosci., vol. 16, fasc. 7, pp. 403–418, lug. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3976

Milde, C., Brinskelle, L. S. & Glombiewski, J. A. Does Active Inference Provide a Comprehensive Theory of Placebo Analgesia?. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging, vol. 9, fasc. 1, pp. 10–20, gen. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2023.08.007

Ongaro e, G. & Kaptchuk, T. J. Symptom perception, placebo effects, and the Bayesian brain. Pain, vol. 160, fasc. 1, pp. 1–4, gen. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001367

Costa, C. et al. Comprehensive investigation of predictive processing: A cross- and within‐cognitive domains fMRI meta‐analytic approach. Hum. Brain Mapp., vol. 45, fasc. 12, p. e26817, ago. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.26817

de Bruin, L. & Michael, J. Prediction error minimization: Implications for Embodied Cognition and the Extended Mind Hypothesis. Brain Cogn., vol. 112, pp. 58–63, mar. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2016.01.009

Gadsby e, S. & Hohwy, J. Predictive Processing and Body Representation. PsyArXiv, preprint, ott. (2021). https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/zvfx2

Kanai, R., Komura, Y., Shipp, S. & Friston, K. Cerebral hierarchies: predictive processing, precision and the pulvinar. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., vol. 370, fasc. 1668, p. 20140169, mag. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0169

Wolpert, D. M., Flanagan, J. R. & prediction. M. Curr. Biol., vol. 11, fasc. 18, pp. R729–R732, set. (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00432-8

Bubic, A., Von Cramon, D. Y. & Schubotz, R. I. Prediction, cognition and the brain. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2010.00025 (mar. 2010).

Sprevak, M. D. & Smith, R. An introduction to predictive processing models of perception and Decision-Making. Top. Cogn. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12704 (2023).

Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a rough guide to the brain?. Trends Cogn. Sci., vol. 13, fasc. 7, pp. 293–301, lug. (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.04.005

Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?. Nat. Rev. Neurosci., vol. 11, fasc. 2, pp. 127–138, feb. (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2787

van der Helm, P. A. Structural coding versus free-energy predictive coding. Psychon. Bull. Rev., vol. 23, fasc. 3, pp. 663–677, giu. (2016). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0938-9

Knill, D. C. & Pouget, A. The Bayesian brain: the role of uncertainty in neural coding and computation. Trends Neurosci., vol. 27, fasc. 12, pp. 712–719, dic. (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2004.10.007

De Ridder, D., Vanneste, S. & Freeman, W. The Bayesian brain: Phantom percepts resolve sensory uncertainty. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., vol. 44, pp. 4–15, lug. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.04.001

Hohwy, J. The predictive processing hypothesis. Oxf. Handb. 4E Cogn. https://doi.org/10.1093/OXFORDHB/9780198735410.013.7 (2018).

Venter, E. Toward an embodied, embedded predictive processing account. Front. Psychol. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.543076 (2021).

Aggelopoulos, N. C. & inference. P. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., vol. 55, pp. 375–392, ago. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.001

Ciria, A., Schillaci, G., Pezzulo, G., Hafner, V. & Lara, B. Predictive processing in cognitive robotics: A review. Neural Comput. 33, 1402–1432. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco_a_01383 (2021).

Eder, A. B. & Dignath, D. Influence of verbal instructions on effect-based action control. Psychol. Res., vol. 81, fasc. 2, pp. 355–365, mar. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-016-0745-6

Damanskyy, Y. & Martiny-Huenger, T. Parks-Stamm, associative learning from verbal Action-Effect instructions: A replication and investigation of underlying mechanisms. J. Cogn. 6 https://doi.org/10.5334/joc.284 (2023).

Cobos, P. L., Vadillo, M., Luque, D. & Pelley, M. L. L. Learned predictiveness acquired through experience prevails over the influence of conflicting verbal instructions in rapid selective attention. PLoS ONE. 13 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200051 (2018).

Lupyan e, G. & Clark, A. Words and the World: Predictive Coding and the Language-Perception-Cognition Interface. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci., vol. 24, fasc. 4, pp. 279–284, ago. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721415570732

Alemanno, F. et al. Efficacy of virtual reality to reduce chronic low back pain: Proof-of-concept of a non-pharmacological approach on pain, quality of life, neuropsychological and functional outcome. PLOS ONE, vol. 14, fasc. 5, p. e0216858, mag. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216858

Bordeleau, M., Stamenkovic, A., Tardif, P. A. & Thomas, J. The Use of Virtual Reality in Back Pain Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pain, vol. 23, fasc. 2, pp. 175–195, feb. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2021.08.001

Giardulli, B. et al. Real and perceived feet orientation under fatiguing and non-fatiguing conditions in an immersive virtual reality environment. Virtual Real. Giu. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-023-00809-9 (2023).

Nishigami, T. Embodying the illusion of a strong, fit back in people with chronic low back pain. A pilot proof-of-concept study. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 39, 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2018.07.002 (2019).

Gatchel, R. J., Neblett, R., Kishino, N. & Ray, C. T. Fear-Avoidance Beliefs and Chronic Pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther., vol. 46, fasc. 2, pp. 38–43, feb. (2016). https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2016.0601

Luque-Suarez, A., Martinez-Calderon, J. & Falla, D. Role of kinesiophobia on pain, disability and quality of life in people suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med., vol. 53, fasc. 9, pp. 554–559, mag. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098673

Eklund, A. et al. Expectations influence treatment outcomes in patients with low back pain. A secondary analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Pain Lond. Engl., vol. 23, fasc. 7, pp. 1378–1389, ago. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1407

Tsang, S. M. H. et al. The effects of bending speed on the lumbo-pelvic kinematics and movement pattern during forward bending in people with and without low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord., vol. 18, fasc. 1, p. 157, apr. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1515-3

Eldridge, S. M. et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ, vol. 355, p. i5239, ott. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5239

Perret, C. et al. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the fingertip-to-floor test. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil., vol. 82, fasc. 11, pp. 1566–1570, nov. (2001). https://doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2001.26064

Julious, S. A. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm. Stat. 4 (fasc. 4), 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.185 (2005).

Camerone, E. M. et al. The Temporal modulation of Nocebo hyperalgesia in a model of sustained pain. Front. Psychiatry. 13, 807138. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.807138 (2022).

Boyce e, D. & Brosky, J. A. Determining the minimal number of cyclic passive stretch repetitions recommended for an acute increase in an indirect measure of hamstring length. Physiother. Theory Pract., vol. 24, fasc. 2, pp. 113–120, gen. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/09593980701378298

Sansone, L. G. et al. Robustness and static-positional accuracy of the SteamVR 1.0 virtual reality tracking system. Virtual Real., vol. 26, fasc. 3, pp. 903–924, set. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-021-00584-5

Seabold, S. & Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python. scipy, mag. (2010). https://doi.org/10.25080/Majora-92bf1922-011

Leon, A. C. & Heo, M. A comparison of multiplicity adjustment strategies for correlated binary endpoints. J. Biopharm. Stat., vol. 15, fasc. 5, pp. 839–855, (2005). https://doi.org/10.1081/BIP-200067922

Cureton, E. E. & correlation. R. Psychometrika, vol. 21, fasc. 3, pp. 287–290, set. (1956). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289138

He, X., Sun, Q. & Stetler, C. Warm Communication Style Strengthens Expectations and Increases Perceived Improvement. Health Commun., vol. 33, fasc. 8, pp. 939–945, ago. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1322482

Hutchinson, J. C., Sherman, T., Martinovic, N. & Tenenbaum, G. The Effect of Manipulated Self-Efficacy on Perceived and Sustained Effort. J. Appl. Sport Psychol., vol. 20, fasc. 4, pp. 457–472, ott. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200802351151

McKay, B., Lewthwaite, R. & Wulf, G. Enhanced expectancies improve performance under pressure. Front. Psychol. 3 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00008 (2012).

Wulf, G., Chiviacowsky, S. & Lewthwaite, R. Altering mindset can enhance motor learning in older adults.. Psychol. Aging, vol. 27, fasc. 1, pp. 14–21, (2012). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025718

Wulf e, G. & Lewthwaite, R. Conceptions of Ability Affect Motor Learning. J. Mot. Behav., vol. 41, fasc. 5, pp. 461–467, ott. (2009). https://doi.org/10.3200/35-08-083

Kirsch, I. Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behavior. Am. Psychol. 40 (fasc. 11), 1189–1202. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.40.11.1189 (1985).

Kirsch, I. Response expectancy theory and application: A decennial review. Appl. Prev. Psychol., vol. 6, fasc. 2, pp. 69–79, mar. (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80012-5

Grassi, P. R. & Bartels, A. Magic, Bayes and wows: A Bayesian account of magic tricks. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., vol. 126, pp. 515–527, lug. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.04.001

Reisenzein, R. Exploring the Strength of Association between the Components of Emotion Syndromes: The Case of Surprise. Cogn. Emot., vol. 14, fasc. 1, pp. 1–38, gen. (2000). https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300378978

Reisenzein, R., Horstmann, G. & Schützwohl, A. The Cognitive-Evolutionary Model of Surprise: A Review of the Evidence. Top. Cogn. Sci., vol. 11, fasc. 1, pp. 50–74, gen. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12292

Sebastian, A. et al. Surprise: Unexpected Action Execution and Unexpected Inhibition Recruit the Same Fronto-Basal-Ganglia Network. J. Neurosci., vol. 41, fasc. 11, pp. 2447–2456, mar. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1681-20.2020

Gerten e, J. & Topolinski, S. Shades of surprise: Assessing surprise as a function of degree of deviance and expectation constraints. Cognition, vol. 192, p. 103986, nov. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.05.023

Gill, K., Krag, M. H., Johnson, G. B., Haugh, L. D. & Pope, M. H. Repeatability of four clinical methods for assessment of lumbar spinal motion. Spine, vol. 13, fasc. 1, pp. 50–53, gen. (1988). https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-198801000-00012

Merritt, J. L., McLean, T. J., Erickson, R. P. & Offord, K. P. Measurement of trunk flexibility in normal subjects: reproducibility of three clinical methods. Mayo Clin. Proc., vol. 61, fasc. 3, pp. 192–197, mar. (1986). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61848-5

Niehorster, D. C., Li, L. & Lappe, M. The accuracy and precision of position and orientation tracking in the HTC vive virtual reality system for scientific research. -Percept 8, 2041669517708205. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041669517708205 (2017). fasc. 3.

Kuhlmann de Canaviri, L. et al. Static and Dynamic Accuracy and Occlusion Robustness of SteamVR Tracking 2.0 in Multi-Base Station Setups. Sensors, vol. 23, fasc. 2, Art. fasc. 2, gen. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/s23020725

Lindheimer, J. B. et al. Reconceptualizing the measurement of expectations to better understand placebo and nocebo effects in psychological responses to exercise. Eur. J. Sport Sci., vol. 20, fasc. 3, pp. 338–346, apr. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2019.1674926

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Simone Battista for his precious support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MT conceived the study and its protocol; MJ developed the VR scenario. MM, LGS, AV and MJ coordinated the planning, recruitment, and experimental sessions. All authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of the results and contributed to the writing and revision of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Job, M., Manoni, M., Sansone, L.G. et al. A surprise induced by a visual-haptic illusion in virtual reality can lead to motor improvement. Sci Rep 15, 14741 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98243-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98243-1